Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Creole Portuguese - General

Uploaded by

Olga RoussinovaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Creole Portuguese - General

Uploaded by

Olga RoussinovaCopyright:

Available Formats

Creole Portuguese: General

Source: Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications, No. 14, A Bibliography of Pidgin and Creole

Languages (1975), pp. 75-81

Published by: University of Hawai'i Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20006572 .

Accessed: 16/03/2014 08:32

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Hawai'i Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Oceanic

Linguistics Special Publications.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

15. Creole Portuguese: General

Beginning in the latter half of the fifteenth century, the Portuguese spread their language,

mostly in pidginized or creolized forms, as a lingua franca along the coasts of Africa and

Asia, from the Cape Verde Islands to Canton and the Moluccas. In some parts of Asia

cre?le Portuguese (Crioulo or Creoulo) was still used as a lingua franca during the

early nineteenth century, long after the Portuguese trade empire had collapsed. In a few

spots inWest Africa pidgin Portuguese was displaced by pidgin English only after 1850.

In the Cape Verdes and in Sao Tom? and Principe the cre?le dialects came into use on the

first tropical plantations?prototypes of those in the New World?worked by African

slaves. In most areas cre?les developed among Portuguese traders and soldiers, their

mixed-blood families, domestic slaves, mercenaries, and other assimilated natives. In

several places the use of Crioulo was continued by the Dutch and British successors to

Portuguese rule.

The use of pidgin Portuguese in the trading posts and barracoons of West Africa is of

particular interest because some creolists have posited it as the basis of Caribbean cre?le

languages and perhaps other pidgins and cre?les (the relexification theory). Whinnom

(1956) similarly derives the Philippine Spanish cre?les from relexification of Moluccan

Portuguese. The Portuguese element in Saramaccan is obvious; majority opinion sees this

as a holdover from West African pidgin though some attribute it to Brazilian Jewish

masters. The extent of influence of pidgin or cre?le Portuguese on Afrikaans is warmly

disputed; on this point see the section on Afrikaans.

Considerable numbers of African slaves were carried to metropolitan Portugal, where

their speech was reported in literature by Gil Vicente (died 1540) and others; for discus?

sion see Teyssier (1959) and others.

Most descriptions of Portuguese cre?le dialects have been by Portuguese writers who

were sometimes themselves of overseas origin. They were usually amateurs or semi

amateurs and were bound by traditional grammar, but often their work is remarkably

painstaking. Coelho (1880-86) first aroused interest in the dialects, which was fanned by

Schuchardt (1882 if.). Leite de Vasconcellos surveyed the African cre?les (1898) and then

sketched all overseas dialects in his survey of Portuguese dialects (1901). Morais-Barbosa

(19681) has continued this overall interest in Crioulo, but Herculano de Carvalho (1961

if.) has demonstrated the greatest technical mastery of Portuguese cre?le studies.

A survey of the known Crioulo-speaking areas follows. The question of creolization of

Brazilian Portuguese is treated separately. While it is likely that Portuguese has been

pidginized at various places and at various times in Angola and Mozambique, the com?

pilers have found no proof of pidginization except for a passing reference by Richardson

75

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

15. CREOLE PORTUGUESE :GENERAL

(1963) to a barracoon jargon inMozambique. Wurm (1971) mentions pidgin Portuguese in

eastern Timor, but cites no references.

Cape Verde Islands. All the 230,000 inhabitants speak Creole of various grades of assimila?

tion to standard Portuguese; apparently most are bilingual in SP and Crioulo. The dialects,

one to each major island, fall into Windward and Leeward groupings. Although the

islands were first settled in 1462, the first descriptions of Crioulo were by Vieira Botelho

da Costa & Duarte (1886) and Paula Brito edited by Coelho (1887); these were supple?

mented by Schuchardt (1888c). Much later, Lopes da Silva (1957) published a rounded

though somewhat old-fashioned monograph. Oliveira Almada (1961) and Nunes (1963)

have also written on Crioulo. There are abundant texts, e.g. Parsons (1923) and Romano

(1966-67). Doubtless some material remains unpublished; e.g., Ferreira (1959, p. 71) men?

tions a study pursued for thirty years by A. N. Fernandes of Santiago. Studies by modern

linguistic techniques, particularly of the differences from island to island, are mostly

lacking, with the exception of Herculano de Carvalho (1961, 1962).

Suprisingly, there is no religious literature in Crioulo. But, beginning with Teixeira

(1895 to 1899) and going on through the poet Tavares (1932) and several contemporaries,

the dialects have been used for secular literature; see the discussions by Araujo (1966) and

Ferreira (1967a). There is the usual folk literature in the vernacular, a considerable part of

which has been recorded, e.g. by Cardoso (19336) and Parsons (1917 to 1923).

Gui?? (Guinea-Bissau). Portugal planted its first colony on the Gui?? coast in 1669

but parts of the interior were not brought under effective control until the twentieth cen?

tury. Of about 521,000 inhabitants, less than 2 percent are classified as 'civilized,' the rest

presumably speaking African mother tongues. It is noteworthy that the current insur?

rectionists of the independence movement are encouraging Crioulo as a unifying force;

see Chaliant (1967).

There is no information as to the extent to which Crioulo is pidginized or reduced in

structure among tribal speakers. Only the developed coastal cre?le, which has close ties

with Cape Verdean Crioulo and is spoken in three dialects, has been described. Bertrand

Bocand? briefly sketched the Crioulo in 1849; Schuchardt wrote on it (1888/?); Marques

de Barros, a cre?le cleric, described it at length (1897-1907); Wilson gives a short con?

temporary account (1962) which lacks adequate texts. Morais-Barbosa has a description

forthcoming. Except incidentally, even the oral literature in Crioulo has not been re?

corded, and there appears to be neither religious nor secular written literature.

Ziguinchor, formerly part of Gui??, was transferred to S?n?gal in 1886. An offshoot of

Gui?? Crioulo known as Kriy?l, described briefly by Chataigner (1963), is spoken in

Ziguinchor and Dakar as the mother tongue of ca. 42,000 persons. Doneux (n. d.) adds a

little information and Esvan published a catechism (1922) inKriy?l.

Sao Tom? (pop. ca. 60,000) and Principe (ca. 5000) were colonized beginning in 1485 and

1500, respectively. Schuchardt first collected the scanty information on the closely related

dialects of S?o Tom? (1882a) and Principe (1889a), which locally are called Forro. Almada

Negreiros published an amateur's description of Sao Tom? Crioulo (1895), and Valkhoff,

a short but professional account many years later (1966). Luiz Ferraz of the University of

theWitwatersrand ismaking a detailed study of the dialect. Reis (1965, 1969) has made

some of its folklore available. Only recently have local writers begun to use a little Crioulo in

belles lettres (Moser 1969). There is no description of the Principe dialect, but Wilfried

G?nther of the Philipps-Universit?t Marburg/Lahn iswriting a dissertation on it. Ferraz

76

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

15. CREOLE PORTUGUESE :GENERAL

has gathered material on a third cre?le, that spoken by the Angolares, descendants of

shipwrecked slaves who remained outside the plantation system; it is reported to have a

considerable Bantu (Kimbundu) element.

Annob?n (Ano Bom) Crioulo is spoken by only ca. 2000 persons including emigrants to

Fernando P?o and elsewhere. Settled early in the sixteenth century, the island was left

to self-rule over long periods and passed to the Spanish flag in 1778. Its isolation has

produced a rather archaic dialect subject to Spanish rather than Portuguese influence.

Schuchardt brought the Fa d'Ambu to attention in 1888, but our knowledge of it rests

on the work of two priests, who at a generation's interval each produced a catechism

and a traditional grammar, Vila (1891a, 18916) and Barrena (1928, 19572).

Indo-Portug?ese. Portuguese trade in India began in 1498 and Goa, the seat of govern?

ment, was conquered in 1510. Other colonies and trading posts were founded from time to

time, the resulting communities often surviving the loss of commercial and military

power. Melo Lopes (1936) gives a comprehensive survey of the use of Portuguese in India

and elsewhere in the Orient but does not differentiate between standard and pidgin/creole

varieties. Schuchardt (18896) surveyed Indo-Portuguese in general, and he and Dalgado

between them sketched, rather than described, some surviving cre?le and semi-creole

dialects: Diu (Schuchardt 1883a), Dam?o (Dalgado 1903), Bombay and vicinity (Dalgado

1906), G?a (Dalgado 1900), Cochin (Schuchardt 1882Z>), Mah? and Cannanore (Schuch?

ardt 1889c), and Mangalore (Schuchardt 1883a1). They and Moniz Junior (1900) give a

few texts. Hancock (1971) lists over 40 other communities in India and several in Indo?

China where cre?le or pidgin Portuguese was once spoken. Laurentiu Theban of the

University of Bucharest has found that only a few remnants remain of the dialects de?

scribed by Dalgado and Schuchardt; however, at Korlai, Chaul, a hitherto undescribed

norteiro dialect is spoken by about 700 persons.

Ceylon is a special case of Indo-Portuguese because the dialect was used so and so

long

extensively. Portuguese conquest of the coast began in 1517 and Portugal's last stronghold

was captured by the Dutch in 1658. The Dutch (1656-1796), and after them the

British,

continued to use Crioulo as a lingua franca. The first description of Crioulo was by Ber

renger (18112), who was followed by by Fox (18191). Dalgado, when the dialect was sup?

posed to be in full decline, produced a full-scale monograph on it (1900), and Ta vares de

Mello published several texts of folk literature (1907/08 to 1914). Hesseling (1910) also

attests to the continued use of the dialect among the mestizo Dutch Burghers. Though

Crioulo appears on the way to extinction as an urban D. E. Hettiaratchi of Vidyo

dialect,

daya University (1969) has found 300-400 creole-speaking rural families at Uppodai near

Batticaloa.

An abundance of religious literature was produced by the Wesleyan mission, including

translations of the Psalms (18211), theNew Testament (18261), the Pentateuch (1833), the

Book of Common Prayer (18201), and Lloyd's catechism (n.d.), and periodical literature

extending into the twentieth century. The Roman Catholics and independent Catholics

also wrote in Crioulo, and there was a little secular writing.

Indonesia andMalaysia. At Batavia (now Jakarta) in Java, never held by the Portuguese, the

Dutch mixed-blood community and its slaves used Crioulo until about 1800, and in the

nearby village of Tugu the dialect continued until after 1900. This dialect was the subject

of a monograph by Schuchardt (1890), supplemented by Huet (1909).

The Portuguese held Malacca from 1511 to 1641, and perhaps 6000 of their descend

77

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

[1. 15. CREOLE PORTUGUESE: GENERAL

ants, largely fishermen, still speak what they term Papia Kristang. It has been described

and illustrated at length in traditional fashion by Silva R?go (1942) and sketched pro?

fessionally but briefly by Knowlton (1964) and Hancock (1969, 1970a). The dialect has

been carried to Singapore, where it is spoken by a cosmopolitan offshoot of the Malaccan

community (Teixeira 1963).

Macao (Macau) and Hong Kong. A Portuguese settlement was established in Macao in

1557, resulting in a mixed-blood, creole-speaking community. The population is predom?

inantly Chinese. Of the ca. 8000 Portuguese only a few hundred speak Crioulo. The

dialect was carried to Hong Kong, where it is spoken by possibly as many as 2000. At

both places it is now in decline. Note, however, the recent literary work in 'Patois' by

Ferreira (1967). First sketched by Leite de Vasconcellos (1892), the dialect was later de?

scribed at length in traditional fashion, with texts, by Marques Perreira (1899-1901).

More recently it has been treated by Nogueira Batalha (1953 to 1968), Thompson (1959

to 1967), and Morais-Barbosa (1968), and locally by Barreiros (1943-44). Batalha is

publishing a detailed glossary of macaista words in Revista Portuguesa de Filolog?a, begin?

ning with 15:144-150 (1969/71 [1973]).

Angola and Mozambique. One would expect cre?le dialects to have developed in these two

long-standing colonies, but the compilers have found no reference to such. Moser (19696)

refers to the use in literature of the broken Portuguese (pequeno-portugu?s or pretogu?s)

spoken by illiterate Africans in the cities of Angola. Language contacts in these two

countries merit study but are not likely to receive it under present political conditions.

Included are works dealing with the expansion of the Portuguese language and its

creolization in many places ; the reciprocal influence of Portuguese and other languages ;

early West African pidgin Portuguese; works dealing with several areas; necrologies of

Portuguese creolists.

Derek. 1971. Rethink? los . . .', RPF 1:617-620.

BICKERTON, [3.

ing pidgin genesis', unpub. paper, first

-. 19476. 'Adolfo Coelho e a

draft, ca. Nov. 1971. 22 p. typescript. [1.

filolog?a portuguesa e alam?o no s?culo

Attributes much of the structure of early cre?le Biblos 23:607-691. in

XIX', Summary

Portuguese and afterwards of other Atlantic

cre?les to West Africans who set them? RPF 2:370-372 (1948). [4.

European

selves to learn Portuguese as a trade language or Bare mention of Coelho's work on cr?oles, p.

learned it from one another in barracoons. 686.

BLAKE, John William (ed. and tr.). 1942. BOXER, C[harles] R[alph]. 1965. The

Europeans in West Africa, 1450-1560. Dutch seaborne empire 1600-1800. Lon?

Documents to illustrate the nature and

don: Hutchinson & Co., Ltd. 326 p. [5.

scope of Portuguese enterprise in West

Portuguese influence on superseding Dutch

Africa, the abortive attempts of Castilians colonists through intermarriage, leading to the

to create an and the use of Portuguese patois as home language, p.

empire there, early

221-226.

English voyages to Barbary and Guinea.

Vol. 1. London :Printed for the Hakluyt BRADSHAW, A. T. von S. 1965. Ves?

Society, xxxvi, 246 p. [2. tiges of Portuguese in the languages of

Incidental information on the use of trade Sierra Leone', SLLR 4:5-37. [6.

Portuguese. Lexical; but briefly discusses early language

Tn contacts, p. 6-9.

BOLEO, Manuel de Paiva. 1947a.

?

memoriam . . . J. Leite de Vasconcel BRANCO, Bernardes. 1882-85. A lin

78

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

15. CREOLE PORTUGUESE: GENERAL [22.

goa nas regi?es orientais', records', unpub. paper, 13 p. typescript.

portuguesa

Boletim da Sociedade de Geographia [14.

Commercial do Porto 2:118-119. [7. ENTWISTLE, William J[ames]. 1936.

?1940. 'Das Suffix des The Spanish language together with Por?

BRUCH, J[osef].

"Crioulo" in Fest? tuguese, Catalan and Basque. London:

portugiesischen ',

der Universit?t K?ln zu den por? Faber & Faber Ltd. vii, 367 p. [15.

schrift

tugiesischen Staatsfeiern des Jahres 1940, -. - 2d ed. Ibid,

1962. xiii,

p. 99-100. [8. 367 p. [16.

C?SAR, Am?ndio. 1967. Par?grafos de Trenchant discussion of cre?le Portuguese, p.

ultramarina. Socie? 313-316, and Brazilian Portuguese, 316-323.

literatura [Braga?]

dade de Expans?o Cultural. 346 p. [9. FLASCHE, H[ans]. 1937. Review of D.

Discusses overseas writers but barely mentions de Mel? Lopes (1936), RF 51:246-248.

Crioulo writings. [17.

COELHO, Francisco] Adolpho (orAdolfo). HAIR, P. E. H. 1966. The use of

1880-86. 'Os dialectos rom?nicos ou African in

languages Afro-European

neo-latinos na ?frica, Asia e Am?rica.' contacts in Guinea, SLLR

1440-1560',

[10. 5:5-26. [18.

Covers Portuguese creole-speaking areas and The Portuguese trained native interpreters,

Brazil. which gave them a head start in trade.

CUST, Robert Needham. 1883. A HART, Thomas R., Jr. 1959. The over?

sketch of the modern languages of Africa. seas dialects as sources for the history of

London: Tr?bner & Co. 2 vols. [11. Portuguese pronunciation', in III Colo?

Internacional de Estudos Luso

Mixed Portuguese of West Africa, p. 43-49. quio

Brasileiros 1957, Actas 1:261-272. [19.

DALGADO, Sebasti?o Rodolfo. (See also

Contains some comment on creolists, especially

A. X. SOARES.) 1916. Contributes

Dalgado.

para a lexiologia [sic] luso-oriental.

Coimbra: Imprensa daUniversidade. 192 JOHNSTON, Sir Harry [Hamilton]. 1906.

Liberia.. . . London: Hutchinson& Co.

p. (Separate from Boletim da Segunda

2 vols., xxviii, 519; xvi, 521-1183 p. [20.

Classe, Vol. 9, Academia das Ciencias de

Early Portuguese pidgin, 1:48-49.

Lisboa.) [12.

Detailed treatment of individual loanwords LOPES, David de Mel?. 1936. A expan?

from Asian languages, including material not used s?o da no Oriente

lingua portuguesa

in the Gloss?rio.

durante os s?culos XVI, XVII e XVIII. . .

-. 1919-21. Gloss?rio luso-asi?tico. Barcelos: Portucalense Editora Lda.

2

Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade. xii, 188 p. [21.

vols., 1919 and 1921. [13. Reviewed: Jos? Pedro Machado in BF(L)

influence of Asian lan? 4(3/4)-.381-386; H. Flasche in RF 51:246-248.

Historical-philological:

Contains much valuable historical and biblio?

guages on Portuguese and through it on other

graphical material but does not differentiate

European languages. Detailed treatment of each

word on the lines of O.E.D. between standard and pidgin/creole Portuguese.

Bibl., p. lv-lxvii. For

English translation see A. X. Soares.

LOPES, Edmundo Correia. 1941. 'Dia?

Reviews reprinted in Port, translation in RL

24:298-305; J. Bloch in Journal Asiatique (1919); lectos crioulos e etnograf?a crioula',

M. Longworth Dames in JRAS (1921); A. BSGL 59:415-435. Reprinted inMorais

Meillet in BSLP 21: 207 (1919); H. Schuchardt in

LGRP 41:339-341 Barbosa (1967), p. 405-430. [22.

(1920).

Deals almost entirely with Portuguese cre?les,

DILLARD, J[oey] L. 1971? Creole as 'vasto laboratorio de ra?a e de

envisaged

Portuguese and cre?le English : the early cultura.' Emphasizes tendency to reduce gram

79

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

[23. 15. CREOLE PORTUGUESE: GENERAL

mar to the barest possible minimum. Compares Forum

discovered', African 2(4):78-96.

developments in various regions.

[31.

MACHADO, Jos? Pedro. 1936. Review Discusses literature from the Cape Verdes, S.

of David de Mel? Lopes (1936), BF (L) Tom? e Pr?ncipe, and Angola, with special notice

of the Cape Verdean Tavares

4(3/4): 381-386. [23. Eugenio (1867

1930).

MARGARIDO, Alfredo. 1960. Cr?ni?

-. 19696. in

cas de Lisboa: A dos crioulos Essays Portuguese

forma?ao

African literature. University Park, Pa.:

portugueses', Cabo Verde 11 (132):

The Pennsylvania State Univ. 88 p. (The

3-5. [24.

Pennsylvania State Univ. Studies, no.

A general treatment resting on Silva Neto, A

lingua portuguesa no Brasil. 26.) [32.

-. 1962. 'The social and economic NEMESIO, Vitorino. ?1948. 'Perfil de

of Portuguese negro

Adolfo Coelho', Revista da Faculdade de

background poetry',

37:50-74. Letras de Lisboa 14: 23-46. Summary in

Diogenes [25.

and in Cape

RPF2: 433-434. [33.

Folk literary poetry Verdean

Crioulo (p. 56) and folk poetry in S?o Tom? Forro NOGUEIRA, Rodrigo de S?. 1930. 'Da

(58); corrupt Portuguese spoken in Angola (70). necessidade de se estudiar a nossa

MATOS, Luis de. 1968. 'O portugu?s? Portu?

dialectolog?a colonial', Lingua

lingua franca no Oriente', in Coloquios 1:280-281.

guesa [34.

sobre as provincias do Oriente 2:11 Creole dialects are valuable for survivals of

23. [26. earlier stages of Portuguese.

On Portuguese generally; no special mention Oscar Bastian. 1957. 'Reflex

PINTO,

of cre?le.

?es acerca da expans?o da lingua portu?

MATTA, J. D. Cordeiro da. 1893. En guesa no mundo', in Anais do Congresso

saio de diccionario kimb?ndu-portuguez. Brasileiro de Lingua Vern?cula 2: 152?

Lisboa: Casa Editora Antonio M. 193; summary in A nais 3: 460-461.

Pereira. xvi, 172 p. [27. [35.

Specimens of Cape Verde and S. Thom? dialect, A diffuse article, useful for quotations from and

p. xiv-xv. citations of old writers and D. Lopes (1936) on

Portuguese in the Orient.

MORAIS-BARBOSA, Jorge. ?1968. A

no QUADROS, J?nio. 1966. Curso pr?tico

lingua portuguesa mundo. Lisboa:

da lingua portuguesa e sua literatura. Vol.

Sociedade de Geograf?a. 192 p. [28.

1. S?o Paulo: Editora Formar Ltda.

-. 1969.

-2.a revista.

edi?ao, 408 p. [36.

Lisboa: Ag?ncia-Geral do Ultramar.

List of crioulo dialects, p. 61-63. Story of the

170 p. [29. Prodigal Son in 4 Indo-Portuguese dialects,

63-64.

A competent survey. 'Os crioulos,' p. 113-121;

'O portugu?s no Brasil,' 121-123; 'A difus?o da 1959. Historia da

no 'In?

RIBEIRO, Joaquim.

lingua portuguesa Oriente,' 123-124;

fluencia do portugu?s em l?nguas orientais,' 124? romaniza?ao da Am?rica. Rio de Janeiro:

128; 'Influencia do portugu?s em l?nguas afri? Servi?o Nacional de Teatro, Ministerio

canas,' 128-133. Bibl., 159-168.

da Educa?ao e Cultura. 322 p. [37.

MOSER, Gerald M. 1962. 'African lit? 'O portugu?s e as l?nguas negro-africanos,' p.

erature in the 246-278, lexical.

Portuguese language',

//. of General Ed. 13:270-304. [30. RODNEY, Walter. 1970. A history of

A good article but has nothing specifically on the Upper Guinea coast, 1545-1800.

Crioulo. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 283

xiii,

-. 1969a. 'African literature in p. [38.

Portuguese: the first written, the last Considerable detail on Portuguese settlements

80

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

15. CREOLE PORTUGUESE: GENERAL [51.

along the coast, showing how creolized trade Strongly emphasizes the role of CP in affecting

Portuguese got started. other creolized languages.

-. 1964. sobre

1888. Bei? Algumas reflexoes

SCHUCHARDT, H[ugo].

os dialectos crioulos. Sao Tom?: Tipo?

tr?ge zur Kenntnis des kreolischen

Romanisch. I. Allgemeineres ?ber das graf?a das Miss?es Cat?licas. Reprinted,

ZRP 12:242

with revisions, inBF(L) 20: 3-12 (1969).

Negerportugiesische',

254. [39. [45.

A general treatment of Portuguese cre?les, with

A general treatment of the Guinea coast, Cape special attention to S?otomense.

Verdes, islands in the Gulf of Guinea, and other

-. 1966. Studies in Portuguese and

Portuguese colonies.

Creole, with special reference to South

SILVA Neto, Serafim da. 1952. Historia

Africa. [46.

da lingua portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro:

Incorporates Valkhoff (1960) and treats also of

Livros de Portugal. 583 p. [40. the Gulf of Guinea dialects and Portuguese

influence on Afrikaans.

General discussion of cre?le languages, p.

431-442, with some good material on early use of VASCONCELLOS, J[os?] Leite de (i.e.,

Portuguese in West African trade.

Leite de Vasconcellos Pereira de MEL?

-. 1957. 'A lingua portuguesa e a LO). 1897/99. 'Dialectos crioulos por?

sua expans?o', in Anais do Congresso tugueses de ?frica (contribui?oes para o

Brasileiro de Lingua Vern?cula 2: 95-123. estudo da dialectolog?a portuguesa)', RL

Summary, Anais 3: 448^50. [41. 5:241-261. [47.

A valuable survey mostly incorporated in the

Mainly theoretical, but gives 'Conspecto dos

Esquisse (1901). Bibl., p. 242-246. Text of Tei

falares crioulos,' p. 115-123. xeira's translation of a passage from Os Lusiadas

into S. Ant?o Crioulo, with grammatical analysis,

SOARES, Anthony Xavier. 1936. Portu? 246-261.

guese vocables in Asiatic languages. From

-. 1901. Esquisse d'une dialectolo?

the Portuguese original of Monsignor

gie portugaise. (Th?se pour le doctorat de

Sebasti?o Dalgado translated into

with additions and com?

l'Universit? de Paris.) Paris & Lisboa:

English notes,

ments. Baroda: Oriental Institute,

Aillaud & Cie. 220 p. [48.

cxxv,

Reviewed :Pedro A. d'Azevedo in RL 8:153-158

520 p. [42.

(1903/05).

Includes a sketch of Dalgado's life and work. Includes short descriptions of virtually all

overseas dialects, including cre?les, with biblio?

TONKIN, Elizabeth. 1971. 'Social as? graphical references.

pects of the development of Portuguese -. 1925/27. 'Monsenhor Sebasti?o

pidgin in West Africa', paper read at R. RL 26:311-323.

Dalgado', [49.

SOAS Language and History in Africa A necrology.

Seminar, 28 Oct. 1971. 10 p. mimeo.

-. 1959. Li?oes de filolog?a portu?

[43. 3.a comemorativa centenario

guesa. ed.,

Discusses the conditions under which simplified do com notas do

autor, enriquecida

Portuguese came to be spoken, with attention to

autor, prendada e anotada por Serafim

theory of formation of pidgins and cre?les.

Emphasizes role of simplified Portuguese in da Silva Neto. Rio de Janeiro: Livros de

Africa.

Portugal, xxx, 492 p. [50.

VALKHOFF, Marius[-Francois]. 1960. V?ZQUEZ CUESTA, Pilar, and Maria

'Contributions to the study of Creole. Albertina MEND?S da LUZ. 1961.

II. An historic language: Creole Portu? Gram?tica portuguesa. 2.a ed. Madrid:

guese', AfrS 19:113-125. [44. Editorial Gredos. 551 p. [51.

Reviewed: Albano Monteiro Soares in RPF Brief sketch of most cre?les, p. 102-110;

12:270-272 (1962/63). mention of a cr?ole on Timor.

81

This content downloaded from 89.179.117.36 on Sun, 16 Mar 2014 08:32:33 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Mateus, María Helena, and Ernesto D'andrade (2000), The Phonology of PortugueseDocument9 pagesMateus, María Helena, and Ernesto D'andrade (2000), The Phonology of PortugueseBrian Henry0% (1)

- Popular Cuban Music - Emilio Grenet 1939Document242 pagesPopular Cuban Music - Emilio Grenet 1939norbertedmond100% (18)

- Dutch Lady NK Present Isnin 1 C PDFDocument43 pagesDutch Lady NK Present Isnin 1 C PDFAbdulaziz Farhan50% (2)

- Classical Myths in Italian Renaissance PaintingDocument259 pagesClassical Myths in Italian Renaissance PaintingOlga Roussinova100% (1)

- The Mystery of Belicena Villca - Nimrod de Rosario - Part-1Document418 pagesThe Mystery of Belicena Villca - Nimrod de Rosario - Part-1Pablo Adolfo Santa Cruz de la Vega100% (1)

- Cape Verde CreoleDocument17 pagesCape Verde CreoleJoabe Souza100% (1)

- Texto S. MufweneDocument1 pageTexto S. MufweneLuiza OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Language Contact and Variation in Cape Verde and São Tomé and PríncipeDocument38 pagesLanguage Contact and Variation in Cape Verde and São Tomé and PríncipeSamuel EkpoNo ratings yet

- Braziian PortugueseDocument12 pagesBraziian PortugueselingNo ratings yet

- Two Indo-Portuguese Creoles in Contrast PDFDocument46 pagesTwo Indo-Portuguese Creoles in Contrast PDFSahitya Nirmanakaranaya Sahitya NirmanakaranayaNo ratings yet

- He Double Nature of Brazilian Portuguese: Daughter and Sister of European PortugueseDocument11 pagesHe Double Nature of Brazilian Portuguese: Daughter and Sister of European PortugueseInternational Journal of Arts and Social ScienceNo ratings yet

- AngolaDocument42 pagesAngolakilembeNo ratings yet

- U CH ResearchDocument11 pagesU CH ResearchdeniseyarnoldNo ratings yet

- ComparativeDocument19 pagesComparativeJohn-Paul MollineauxNo ratings yet

- 500 Years of Native Brazilian History: Diálogos LatinoamericanosDocument14 pages500 Years of Native Brazilian History: Diálogos LatinoamericanosJamille Pinheiro DiasNo ratings yet

- Palmares: An African State in Brazil by R. K. KentDocument18 pagesPalmares: An African State in Brazil by R. K. KentDmitri BeliaevNo ratings yet

- Chap 3Document16 pagesChap 3VICTOR MBEBENo ratings yet

- Brazilian TraditionDocument11 pagesBrazilian TraditionPan CatNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On "Pidgins AND Creoles": Submitted To:-Submitted BYDocument12 pagesA Project Report On "Pidgins AND Creoles": Submitted To:-Submitted BYmanish3765No ratings yet

- Trinidad's French Creole Linguistic and Cultural Heritage: Documentation and Revitalisation IssuesDocument16 pagesTrinidad's French Creole Linguistic and Cultural Heritage: Documentation and Revitalisation IssuesTiffany Khan-SooknananNo ratings yet

- NAVARRO 2001 Traduções para o Tupi (2859)Document23 pagesNAVARRO 2001 Traduções para o Tupi (2859)Ana PassosNo ratings yet

- Non CreolDocument46 pagesNon CreolAisha Islanders PérezNo ratings yet

- Nolan - Lingua Franca - A Not So Simple Pidgin (2015)Document13 pagesNolan - Lingua Franca - A Not So Simple Pidgin (2015)Firmin DoduNo ratings yet

- Some Descriptions of Leprosy in The Ancient Medical Literature of CeylonDocument8 pagesSome Descriptions of Leprosy in The Ancient Medical Literature of CeylonJigdrel77No ratings yet

- Pidgin and Creole LanguagesDocument15 pagesPidgin and Creole LanguageszidnalNo ratings yet

- Jacobs Parkvall The Lesser Antillean Origins of Guianese 2022Document41 pagesJacobs Parkvall The Lesser Antillean Origins of Guianese 2022profakarollinyuniversidadeNo ratings yet

- Satra 4Document2 pagesSatra 4yeseki8683No ratings yet

- Portuguese LanguageDocument21 pagesPortuguese LanguageAndrei ZvoNo ratings yet

- Rodrigo Budasz - Black Guitar-Players and Early African-Iberian Music in Portugal and BrazilDocument20 pagesRodrigo Budasz - Black Guitar-Players and Early African-Iberian Music in Portugal and BrazilLeo FrançaNo ratings yet

- Capoeira WheelDocument8 pagesCapoeira WheelIsak HouNo ratings yet

- Budasz - Black Guitar-Players and Early African-Iberian MusicDocument20 pagesBudasz - Black Guitar-Players and Early African-Iberian MusicFrancisco Valdivia SevillaNo ratings yet

- Pidgins and Pidginization PDFDocument14 pagesPidgins and Pidginization PDFarielle mafoNo ratings yet

- Tirilongosramirez 1973Document9 pagesTirilongosramirez 1973Lazlo LozlaNo ratings yet

- Créolité, Creolization, and Contemporary Caribbean CultureDocument20 pagesCréolité, Creolization, and Contemporary Caribbean Culturepaula roaNo ratings yet

- RafaelDietzsch Brasilica SpecimenDocument15 pagesRafaelDietzsch Brasilica SpecimenVítor MarquesNo ratings yet

- Muysken. - Uchumataqu: Research in Progress On The Bolivian AltiplanoDocument19 pagesMuysken. - Uchumataqu: Research in Progress On The Bolivian AltiplanoRoger R. Gonzalo Segura0% (1)

- Capoeira Wheel PDFDocument8 pagesCapoeira Wheel PDFAzik KunouNo ratings yet

- Practical Work Nº2 MarcoDocument4 pagesPractical Work Nº2 MarcoVir UmlandtNo ratings yet

- Portuguese Loan-Words in The Toponymy of Ambon: A Historical-Archaeological PerspectiveDocument8 pagesPortuguese Loan-Words in The Toponymy of Ambon: A Historical-Archaeological PerspectiveRam DaniNo ratings yet

- 6997-Texto Do Artigo-18055-1-10-20190716Document29 pages6997-Texto Do Artigo-18055-1-10-20190716Raffaela MouraNo ratings yet

- Victoria Troianowski Saramago Transatlantic SertoesDocument19 pagesVictoria Troianowski Saramago Transatlantic SertoesVictoria AlcalaNo ratings yet

- Wayward Daughter Language Contact inDocument26 pagesWayward Daughter Language Contact inSamuel EkpoNo ratings yet

- Lingua FrancaDocument60 pagesLingua FrancaTarek طارق Kahlaoui الكحلاويNo ratings yet

- A Typology of The Prestige LanguageDocument15 pagesA Typology of The Prestige Languageashanweerasinghe9522100% (1)

- Recepção Do Lusotropicalismo Nas Colonias Portuguesas. Ercilio LangaDocument29 pagesRecepção Do Lusotropicalismo Nas Colonias Portuguesas. Ercilio LangaErcilio LangaNo ratings yet

- How Is Creole A LanguageDocument10 pagesHow Is Creole A LanguageMamieyn SadiqNo ratings yet

- The Survival of Arabic in MaltaDocument11 pagesThe Survival of Arabic in MaltaIrina ButunoiNo ratings yet

- Kawahara, Toshiaki - A Study of Literacy in Pre-Hispanic PhilippinesDocument14 pagesKawahara, Toshiaki - A Study of Literacy in Pre-Hispanic PhilippinesBrian LeeNo ratings yet

- A Study of Literacy in Pre-Hispanic Philippines: Toshiaki Kawahara Kyoto Koka Women's UniversityDocument14 pagesA Study of Literacy in Pre-Hispanic Philippines: Toshiaki Kawahara Kyoto Koka Women's UniversityKitkatNo ratings yet

- The Portuguese Cultural Imprint On Sri LankaDocument8 pagesThe Portuguese Cultural Imprint On Sri LankaMindStilledNo ratings yet

- Pidgin Nurul2011Document5 pagesPidgin Nurul2011Nurul-Akmar ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Van Rensburg. The First Afrikaans.Document11 pagesVan Rensburg. The First Afrikaans.kayNo ratings yet

- The Negro RiverDocument12 pagesThe Negro RiverAzeem Hopkins Bey100% (1)

- Peter Mark, Marfins Serra Leoa PDFDocument31 pagesPeter Mark, Marfins Serra Leoa PDFPaulo Alexandre ContreirasNo ratings yet

- Richard Allsopp (Bridgetown, Barbados) - Caribbean English As A Challenge To LexicographyDocument11 pagesRichard Allsopp (Bridgetown, Barbados) - Caribbean English As A Challenge To LexicographyТатьяна ВороноваNo ratings yet

- Chabacano IdentityDocument33 pagesChabacano IdentityRoel MarcialNo ratings yet

- Examine The Grammatical Relevance of Pigeon Language in A MultiDocument31 pagesExamine The Grammatical Relevance of Pigeon Language in A MultiArthur PentaxNo ratings yet

- 1-Definition (A Really Full Good Definition) 2-History 3-Types or Classes 4-ExamplesDocument8 pages1-Definition (A Really Full Good Definition) 2-History 3-Types or Classes 4-ExamplesVir UmlandtNo ratings yet

- History and Status: Breton Is Attested From The 9th Century. It Was The Language of The Upper Classes Until TheDocument2 pagesHistory and Status: Breton Is Attested From The 9th Century. It Was The Language of The Upper Classes Until TheMrMarkitosNo ratings yet

- French Is Estimated To Have About 7Document8 pagesFrench Is Estimated To Have About 7Divyam ChawdaNo ratings yet

- Gramatica AyoreoDocument10 pagesGramatica AyoreoXuan Lajo MartínezNo ratings yet

- The Portuguese Miscigenation Around The World - Sending in AdvanceDocument15 pagesThe Portuguese Miscigenation Around The World - Sending in AdvanceCDD RDTL QG Assessor MarinhaNo ratings yet

- Leonardo Marques - The Economic Structures of Slavery in Colonial Brazil - Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American HistoryDocument31 pagesLeonardo Marques - The Economic Structures of Slavery in Colonial Brazil - Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American HistoryDaniel SilvaNo ratings yet

- Yonan PDFDocument30 pagesYonan PDFOlga RoussinovaNo ratings yet

- Explorations Within The African Diaspora PDFDocument7 pagesExplorations Within The African Diaspora PDFOlga RoussinovaNo ratings yet

- Carlo Ginzburg Your Country Needs You PDFDocument24 pagesCarlo Ginzburg Your Country Needs You PDFOlga RoussinovaNo ratings yet

- RBI Finance PDFDocument28 pagesRBI Finance PDFbiswashswayambhuNo ratings yet

- Deck Log Book Entries - NavLibDocument9 pagesDeck Log Book Entries - NavLibLaur MarianNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On: A Study On Service Quality of Hotel Industry in RourkelaDocument58 pagesA Project Report On: A Study On Service Quality of Hotel Industry in RourkelaKapilYadavNo ratings yet

- Justice Tim VicaryDocument5 pagesJustice Tim Vicaryاسماعيل الرجاميNo ratings yet

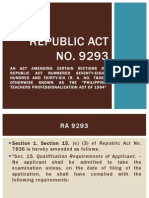

- RA9293Document11 pagesRA9293Joseph LizadaNo ratings yet

- Human Resources Practices in WalmartDocument4 pagesHuman Resources Practices in WalmartANGELIKA PUGATNo ratings yet

- PHN6WKI7 UPI Error and Response Codes V 2 3 1Document38 pagesPHN6WKI7 UPI Error and Response Codes V 2 3 1nikhil0000No ratings yet

- 10.1007@978 3 030 15035 8103Document14 pages10.1007@978 3 030 15035 8103Daliton da SilvaNo ratings yet

- College Board BigFuture College Profile CDS Import 2022 2023Document154 pagesCollege Board BigFuture College Profile CDS Import 2022 2023Nguyen PhuongNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Accounting - Adjusting EntriesDocument4 pagesFundamentals of Accounting - Adjusting EntriesAuroraNo ratings yet

- Nitttr Chandigarh Vacancy NoticeDocument7 pagesNitttr Chandigarh Vacancy Noticelolol lololNo ratings yet

- 3 Expressive Arts - DemoDocument21 pages3 Expressive Arts - DemoJack Key Chan AntigNo ratings yet

- IAS 08 PPSlidesDocument44 pagesIAS 08 PPSlideschaieihnNo ratings yet

- Barcoo Independent 130309Document6 pagesBarcoo Independent 130309barcooindependentNo ratings yet

- Community and Public Health Nursing 2nd Edition Harkness Test BankDocument13 pagesCommunity and Public Health Nursing 2nd Edition Harkness Test BankCarolTorresaemtg100% (11)

- Intentional InjuriesDocument29 pagesIntentional InjuriesGilvert A. PanganibanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Hospitality IndustryDocument49 pagesLesson 2 - Hospitality Industrymylene apattadNo ratings yet

- Code of Virginia Code - Chapter 3. Actions - See Article 7 - Motor Vehicle AccidentsDocument15 pagesCode of Virginia Code - Chapter 3. Actions - See Article 7 - Motor Vehicle AccidentsCK in DCNo ratings yet

- Uttar Pradesh TourismDocument32 pagesUttar Pradesh TourismAnone AngelicNo ratings yet

- English Higher Tier Paoer 1 JuneDocument4 pagesEnglish Higher Tier Paoer 1 Junelsh_ss7No ratings yet

- Prelims 2A Judge - SCORESHEETDocument2 pagesPrelims 2A Judge - SCORESHEETMeetali RawatNo ratings yet

- Quantity SurveyingDocument9 pagesQuantity Surveyingshijinrajagopal100% (4)

- Culture Lect 2Document4 pagesCulture Lect 2api-3696879No ratings yet

- Internship Report Quetta Serena HotelDocument33 pagesInternship Report Quetta Serena HotelTalha Khan43% (7)

- 001) Each Sentence Given Below Is in The Active Voice. Change It Into Passive Voice. (10 Marks)Document14 pages001) Each Sentence Given Below Is in The Active Voice. Change It Into Passive Voice. (10 Marks)Raahim NajmiNo ratings yet

- Browerville Blade - 08/08/2013Document12 pagesBrowerville Blade - 08/08/2013bladepublishingNo ratings yet

- Louis BegleyDocument8 pagesLouis BegleyPatsy StoneNo ratings yet