Professional Documents

Culture Documents

36 Therelationshipbetweenstaticanddynamicocclusionin

36 Therelationshipbetweenstaticanddynamicocclusionin

Uploaded by

HARITHA H.POriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

36 Therelationshipbetweenstaticanddynamicocclusionin

36 Therelationshipbetweenstaticanddynamicocclusionin

Uploaded by

HARITHA H.PCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/8498193

The relationship between static and dynamic occlusion in 14-17-year-old

school children

Article in Journal of Oral Rehabilitation · July 2004

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01283.x · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

12 1,418

2 authors:

Ahmad S Al-Hiyasat Elham S Alhaija

Jordan University of Science and Technology Jordan University of Science and Technology

45 PUBLICATIONS 1,437 CITATIONS 68 PUBLICATIONS 1,376 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

cytotoxicity of dental materials View project

MICRO-OSTEOPERFORATION AND TOOTH MOVEMENT: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRAIL View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Ahmad S Al-Hiyasat on 19 July 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2004 31; 628–633

The relationship between static and dynamic occlusion in

14–17-year-old school children

A. S. AL-HIYASAT* & E. S. J. ABU-ALHAIJA† Departments of *Restorative Dentistry and †Preventive

Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

SUMMARY This study investigated the relationship occlusion (57%) and most of the subjects had no

between static and dynamic occlusion in school posterior contact in protrusive movement (78%).

children. A total of 447 subjects, within an age range There was an association between canine guidance

of 14–17 years with no history of orthodontic treat- with class II static occlusion. Statistically, a signifi-

ment or trauma to the teeth were included in this cant relationship was found between the dynamic

study. Static occlusion was determined for both and static occlusion of the incisor (P < 0Æ001) but not

incisal and molar relationship. Dynamic occlusion with the molar (P > 0Æ05).

was determined in lateral and protrusive move- KEYWORDS: static occlusion, dynamic occlusion, lat-

ments of the mandible. The majority of the subjects eral excursion, protrusion

had class I static occlusion for both incisor and molar

relationship (45 and 54%, respectively). Canine- Accepted for publication 12 March 2003

guided occlusion was the dominant type of dynamic

during mandibular protrusion (3). It appears that there

Introduction

is a contradiction in the literature, as some studies have

The ideal static occlusion has been identified, based on reported a predominance of canine-guided occlusion

the work of Angle in 1907 (1) and later by Andrews in (11, 12), whilst others have found a predominance of

1972 (2). This classification of occlusion was mainly group function (10, 13, 14). Furthermore, others have

based on a description of arch form, tooth position and stated that pure canine guidance or pure group function

tooth contacts in the intercuspal position (3, 4). This rarely exists and balancing contact seems to be the

type of occlusion is given a considerable emphasis by general rule in the population of contemporary civil-

the orthodontist; however, less emphasis is given to the ization (15). Indeed, the conflict between these studies

importance of dynamic or functional occlusion (3). could be related to sample selection, and differences

Two different types of dynamic occlusion have been between subjects investigated such as age, eating habits

reported, canine-protected (canine-guided) occlusion and other patient-related factors (16).

(5–8) and group function (9, 10). Canine guidance The relationship between static and dynamic occlu-

occurs when there is contact only between the working sion has previously been investigated. Scaife and Holt

side canines during lateral excursions of the mandible, (12) reported that canine guidance was associated with

and group function occurs when there is simultaneous class II Angle classification and others have found that

contact of the canine and posterior teeth on the the majority of normal/class I Angle static occlusion

working side during lateral excursions. The two types was associated with balance occlusion (17, 18). How-

of occlusion have a common theme: the absence of ever, other reports have found no significant relation-

contact on the non-working side during lateral excur- ship between static and dynamic occlusion types (19).

sion, and the absence of posterior occlusal contact The sample selection and number of subjects as well

ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 628

STATIC AND DYNAMIC OCCLUSION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN 629

as the methods used to examine the occlusion could be Class II The lower incisor edges lie posterior to the

the reason for the differences in the results of these (div. 2) cingulum plateau of the upper incisors. Upper

studies. Therefore, there is a need for further studies to incisors are retroclined and overjet is usually

evaluate the static and dynamic occlusion in a large minimal but may be increased

number of randomly chosen subjects who had no Class III The lower incisor edges lie anterior to the cingulum

plateau of the upper incisors. The overjet is reduced

previous treatment that could affect the occlusal rela-

or reversed

tionship. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate

the relationship between static and dynamic occlusion

in 14–17-year-old school children.

Molar occlusion. Molar occlusion was defined as follows

(1):

Materials and methods

Class I The mesio-buccal cusp of the lower first molar

Sample occludes between the mesio-buccal cusp of the

upper first molar and the buccal cusp of the

This investigation was carried out on 447 Jordanian second premolar

school pupils, aged 14–17 years. There were 146 males Class II The mesio-buccal cusp of the lower first molar

and 301 females. The inclusion criteria were: the occludes between the two buccal cusps of the

presence of the 28 natural permanent teeth (excluding upper first molar

the third molars); no prior orthodontic treatment; no Class III The mesio-buccal cusp of the lower first molar

occludes anteriorly to the buccal cusp of the

history of trauma or fractured teeth; no large restora-

upper second premolar

tions that included the incisal edge or one or more

cusps.

Half- and quarter-unit class II or class III were

recorded as class II or class III, respectively.

Examination of occlusion

The static and dynamic occlusion of the subjects were

Dynamic occlusion

assessed by a chairside examination with the subjects

seated in a chair in an upright position. Occlusal The dynamic occlusion for both lateral and protrusive

relationship was determined by visual examination movements of the mandible was directly and visually

and tooth contact at the lateral excursion of the determined with the aid of an 8-lm shimstock (Roeko,

mandible was recorded at cusp tip-to-cusp tip position Langenau, Germany) to confirm the contact between

as in previous studies (19). Shimstock was used to the teeth. The examination was carried out as follows:

confirm contact between the teeth. No distinction was

made between the ideal occlusion and the class I Lateral occlusion. Subjects were asked to bite in their

malocclusion. However, the incisor and molar relation- habitual intercuspal position and then slide the man-

ships were assessed and investigated separately. dible into right or left lateral excursion up to cusp tip to

cusp tip contact. The contacts between the teeth in the

working and non-working side were recorded and the

Static occlusion

occlusal contact was classified according to the follow-

Incisor occlusion. Incisor relationship was classified ing criteria (18, 19):

according to the British Standard Institution (BSI) 1. Canine-guided occlusion: canines in contact on the

definition (20) as follows: working side and no occlusal contact in the non-working

side for both right and left lateral excursions.

Class I The lower incisor edges occlude with or lie 2. Group function occlusion: two or more teeth other than

immediately below the cingulum plateau of the the canines in contact on the working side and no

upper central incisors contacts on the non-working side for both left and right

Class II The lower incisor edges lie posterior to the lateral excursions.

(div. 1) cingulum plateau of the upper incisors. Upper

3. Mixed canine guidance/group function occlusion: canine

incisors are proclined and the overjet is increased

guidance on one working side and group function on

ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 31; 628–633

630 A. S. AL-HIYASAT & E. S. J. ABU-ALHAIJA

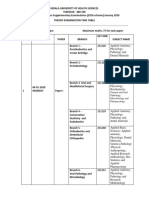

the other working side and no contacts on the non- Table 1. Distribution of subjects to the types of static occlusion

working sides. for incisor and molar relationship

4. Non-working side contact: unilateral or bilateral tooth

Occlusal No. of

contact on the non-working side.

relationship Static occlusion types subjects (%)

Protrusive occlusion. Subjects were asked to bite in the Incisor relationship Class I 202 (45)

Class II (div. 1) 89 (20)

intercuspal position, and to perform a protrusive

Class II (div. 2) 76 (17)

movement of the mandible up to edge-to-edge contact Class III 80 (18)

of the anterior teeth. The contact between the anterior

Molar relationship Class I 239 (54)

teeth and the posterior teeth, if there were any, were

Class II 129 (29)

recorded and the occlusion was classified as follows: Class III 13 (3)

1. Anterior contact with posterior disocclusion in Asymmetric R/L 66 (15)

protrusion.

2. Anterior contact with unilateral or bilateral posterior the subjects had class I for both incisor and molar

contact in protrusion. relationships.

3. No anterior contact with unilateral or bilateral

posterior contact in protrusion.

Before examination of the occlusion, the examiner Dynamic occlusion

explained and demonstrated all the movements of the Table 2 shows the distribution of subjects in relation to

mandible (lateral excursions and protrusion) so that dynamic occlusion (lateral and protrusion). In lateral

each subject understood what he/she had to do. The excursion, the majority of the subjects had canine-

second author (E.S.J.A. – Orthodontist) carried out all guided occlusion. In protrusive excursion, most of the

the examinations of the static occlusion and the first subjects had contact on the anterior teeth with the

author (A.S.A. – Restorative Dentist) carried out all the posterior teeth excluded.

examinations of the dynamic occlusion.

Relationship between static and dynamic occlusion

Reliability

1 Static incisor occlusion versus dynamic occlusion

Intra-examiner reliability was tested by having the

same examiner re-examine thirty randomly chosen Static incisor occlusion versus lateral dynamic occlu-

pupils at an interval of 1 week. There was complete sion. Canine guidance was more dominant in class II

agreement (Kappa ¼ 1) in the repeated examination (div. 1 and 2) followed by class I while the prevalence

for the static occlusion. For the dynamic occlusion of non-working side contact dominated in class III. Chi-

Kappa values were 0Æ83 and 0Æ86 for the lateral and square test showed significant differences in the distri-

protrusive excursions, respectively. bution of the dynamic occlusal relationship in lateral

Table 2. Distribution of subjects to the types of dynamic occlu-

Statistical analysis sion for lateral and protrusive excursions of the mandible

Data were transferred from coded sheets to a personal

Mandibular Type of No. of

computer and analysed using SPSS program. excursions dynamic occlusion subjects (%)

Chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of

Lateral Canine guidance 253 (57)

different occlusal characteristics.

excursion Group function 57 (13)

Mixed (canine guidance 76 (17)

Results and group function)

Non-working-side contact 61 (14)

Protrusive Anterior teeth contact with 350 (78)

Static occlusion excursion disocclusion of posterior teeth

Anterior and posterior teeth contact 80 (18)

The distribution of subjects according to incisor and

No anterior teeth contact 17 (4)

molar relationships is shown in Table 1. The majority of

ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 31; 628–633

STATIC AND DYNAMIC OCCLUSION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN 631

Table 3. Distribution (%) of dynamic occlusion types (lateral and protrusion) in relation to the static occlusion types of the incisor

relationship

Static occlusion Dynamic occlusion types

types

Lateral excursion* Protrusion**

Anterior teeth No anterior teeth

Canine Group contact with Anterior and contact with

Incisor guidance function Mixed Non-working- posterior posterior posterior teeth

relationship (CG) (GF) CG + GF side contact Total disocclusion teeth contact contact Total

Class I 114 (56) 25 (12) 45 (22) 18 (9) 202 (100) 176 (87) 22 (11) 4 (2) 202 (100)

Class II (div. 1) 60 (67) 10 (11) 7 (8) 12 (14) 89 (100) 63 (71) 17 (19) 9 (10) 89 (100)

Class II (div. 2) 62 (82) 6 (8) 6 (8) 2 (3) 76 (100) 75 (99) 1 (1) 0 (0) 76 (100)

Class III 17 (21) 16 (20) 18 (23) 29 (36) 80 (100) 36 (45) 40 (50) 4 (5) 80 (100)

Total 253 (57) 57 (13) 76 (17) 61 (14) 447 (100) 350 (78) 80 (18) 17 (4) 447 (100)

*v2 ¼ 85Æ6; df ¼ 9; P < 0Æ001.

**v2 ¼ 95Æ6; df ¼ 6; P < 0Æ001.

excursion among the different static occlusal incisor Static molar occlusion versus lateral dynamic occlu-

relationship (P < 0Æ001) (Table 3). sion. Although canine guidance was dominant in all

types of static molar relationship and its prevalence was

Static incisor occlusion versus protrusive dynamic occlu- more associated with class II molars, the chi-square test

sion. Most of the subjects in class I and II (div. 1 and 2) showed no significant differences in the distribution of

incisors had anterior contact with complete posterior the dynamic occlusal relationship in lateral excursion

teeth disocclusion in protrusive movements of the among the different static occlusal molar relationship

mandible. While for those subjects with class III incisors, (P > 0Æ05) (Table 4).

50% had anterior teeth contact associated with contact in

posterior teeth. Chi-square test showed significant dif- Static molar occlusion versus protrusive dynamic occlu-

ferences in the distribution of the dynamic occlusal sion. The majority of the subjects in all types of static

relationship in protrusion among the different static occlusion molar relationship had anterior teeth contacts

occlusal incisors relationship (P < 0Æ001) (Table 3). with complete posterior teeth disocclusion in protrusive

2 Static molar occlusion versus dynamic occlusion movements of the mandible. Chi-square test showed no

Table 4. Distribution (%) of dynamic occlusion types (lateral and protrusion) in relation to the static occlusion types of the molar

relationship

Static occlusion Dynamic occlusion types

types

Lateral excursion* Protrusion**

Anterior teeth Anterior and No anterior

Canine Group contact with posterior teeth contact

Molar guidance function Mixed Non-working- posterior teeth with posterior

relationship (CG) (GF) CG + GF side contact Total disocclusion contact teeth contact Total

Class I 121 (51) 34 (14) 49 (21) 35 (15) 239 (100) 186 (78) 46 (19) 7 (3) 239 (100)

Class II 87 (67) 14 (11) 13 (10) 15 (12) 129 (100) 103 (80) 21 (16) 5 (4) 129 (100)

Class III 5 (39) 2 (15) 4 (31) 2 (15) 13 (100) 8 (62) 4 (31) 1 (8) 13 (100)

Asymmetric R/L 40 (61) 7 (11) 10 (15) 9 (14) 66 (100) 53 (80) 9 (14) 4 (6) 66 (100)

Total 253 (57) 57 (13) 76 (17) 61 (14) 447 (100) 350 (78) 80 (18) 17 (4) 447 (100)

*v2 ¼ 13Æ7; df ¼ 9; P ¼ 0Æ13.

**v2 ¼ 4Æ7; df ¼ 6; P ¼ 0Æ58.

ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 31; 628–633

632 A. S. AL-HIYASAT & E. S. J. ABU-ALHAIJA

significant differences in the distribution of the dynamic high prevalence of canine guidance (unilateral or bilat-

occlusal relationship in protrusion among the different eral) in their subjects (12, 24). However, other studies

static occlusal molar relationship (P > 0Æ05) (Table 4). have reported the dominance of group function (10, 13).

The difference in findings between the two latter studies

and our study could be due to the difference in the age

Discussion

groups as our subjects were much younger. It is a well-

documented fact that tooth wear is correlated with age or

Subjects under investigation

more strictly speaking with the length of time that teeth

The 14–17-year age group was chosen for this study, have been exposed to occlusal function (25–30).

because at this age all the permanent teeth (excluding the We found that only 61 subjects (14%) had non-

third molars) are erupted and if older subjects had been working-side contact in contrast to previous reports

chosen the occlusal relationship might have been affec- which reported that the majority of subjects had non-

ted by tooth wear (14, 18, 21–23). The fact that the working-side contact (16, 17, 19, 22, 31). The younger

number of male subjects was much lower than female age of the subjects in our study could be the reason for

subjects was due to the willingness of the latter to take this difference in the results. Furthermore, it was

part in this study. Nevertheless, there were no significant observed that most of our subjects with non-working-

differences in the data between male and female subjects, side contact (61 subjects) had either a group function

therefore the data was pooled and analysed together. (38 subjects) or mixed occlusion (17 subjects), with

only six subjects of canine guidance occlusion. This

supports the hypothesis that canine guidance is far less

Examination of occlusion

likely to be associated with occlusal interferences on the

Tooth contact was confirmed using shimstock as it is non-working side than group function due to the

thought to be more accurate than the other methods steeply inclined palatal surface of the canine (4).

that have been used previously such as impression The majority of our subjects (78%) had no posterior

materials, occlusal indicator wax, articulating paper and contact between the teeth in protrusive movement of the

dental floss (4, 16, 19). mandible. The prevalence of subjects who had posterior

contact combined with anterior contact was found to be

18%. The 17 subjects (4%) who had only posterior

Static occlusion

contact and no anterior contact at all were those subjects

The prevalence of class II in the current study, namely with anterior open bite, and thus anterior tooth-to-tooth

29% for molar and 37% for incisor (20% div. 1 and contact was impossible. The low prevalence of posterior

17% div. 2), was much higher than that found by teeth contact in protrusion in this study is in agreement

Tipton and Rinchuse (19) (15Æ8%). The prevalence of with results reported by Madone and Ingervall (32) and

class III was only 3% for molar and 18% for incisor in Ingervall et al. (14). On the other hand, Sadowsky and

the current study compared with 6Æ9% in the study by BeGole (31) and Sadowsky and Polson (33) found a

Tipton and Rinchuse (19). The differences found may different prevalence of posterior tooth contact in protru-

be because the number of subjects in our study was sion in a similar population of orthodontic patients, 50%

much greater than that of Tipton and Rinchuse (19) of the subjects were reported to have posterior tooth

and as they classified occlusion by Angle’s classification, contact in the first study compared with 20% in the

which is based on molar relationship only. Further- second study. This variations in the results was suggested

more, the prevalence of the type of occlusion may vary by the authors to be caused by the difference in the

from one racial group to another. technique used by different examiners.

Dynamic occlusion Relationship between static and dynamic occlusion

From the 447 subjects in this study, 253 (57%) had For the relationship between static and dynamic

canine guidance and 76 (17%) had mixed occlusion of occlusion the results showed that canine guidance

which one side was canine guided. Our findings are in was associated with class II (for both molar and incisor

agreement with previous reports which also showed a relationship) followed by class I and was least associated

ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 31; 628–633

STATIC AND DYNAMIC OCCLUSION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN 633

with class III. These results compared favourably with 17. Ingervall B. Tooth contact on the functional and non-

the study by Scaife and Holt (12). functional side in children and young adults. Arch Oral Biol.

1972;17:191–200.

The prevalence of posterior contact in protrusion was

18. Rinchuse DJ, Sassouni V. An evaluation of eccentric occlusal

dominantly associated with class III occlusion incisor contacts in orthodontically treated subjects. Am J Orthodont.

and molar relationship (50 and 31%, respectively) 1982;82:251–256.

perhaps because of the reduced or reversed overbite 19. Tipton RT, Rinchuse DJ. The relationship between static

and overjet of the anterior teeth, while the least was occlusion and functional occlusion in a dental school popu-

associated with class II molar and class II div. 2 incisor lation. Angle Orthodont. 1991;61:57–66.

20. British Standard Institution. British standard glossary of dental

(16 and 1%, respectively).

terms, BS, 4492. London, HMSO; 1983.

Finally, the results of this study have demonstrated 21. Reinhardt GA. Attrition and the edge-to-edge bite. A.

that there is a relation between the types of static Anthrobiological study. Angle Orthodont. 1983;53:157–164.

occlusion and certain types of dynamic occlusion. 22. Rinchuse DJ, Sassouni V. An evaluation of functional occlusal

interferences in orthodontically treated subjects. Angle

Orthodont. 1983;53:122–130.

References 23. Egermark-Eriksson I, Carlsson GE, Magnusson T. A long-term

epidemiological study of the relationship between occlusal

1. Angle EH. Treatment of malocclusion of the teeth. 7th ed. factors and mandibular dysfunction in children and adoles-

Philadelphia (PA), SS White Manufacturing Company; 1907. cents. J Dent Res. 1987;66:67–71.

2. Andrews LF. The six keys of normal occlusion. Am J 24. Yaffe A, Ehrlich J. The functional range of tooth contact in

Orthodont. 1972;62:296–309. lateral gliding movements. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;57:730–733.

3. Clark JR, Evans RD. Functional occlusal relationship in a 25. Molnar S, Mckee JK, Molnar IM, Przybeck TP. Tooth wear

group of post-orthodontic patients: preliminary findings. Eur J rates among contemporary Australian aborigines. J Dent Res.

Orthodont. 1998;20:103–110. 1983;62:562–565.

4. Clark JR, Evans RD. Functional occlusion: I. a review. 26. Carlsson GE, Ingervall B. The dentition: occlusal variations

J Orthodont. 2001;28:76–81. and problems. In: Mohl ND, Zarb GA, Carlsson GE, Rugh JD,

5. Kaplan RL. Concepts of occlusion. Gnathology as a basis for a eds. A textbook of occlusion. Chicago (IL), Quintessence Pub-

concept of occlusion. Dent Clin N Am. 1963;7:577–590. lishing Company; 1988.

6. Stuart H, Stallard CE. Concepts of occlusion-what kind of 27. Ekfeldt A, Hugoson A, Bergendal T, Helkimo M. An individual

occlusion should recusped teeth be given? Dent Clin N Am. tooth wear index and an analysis of factors correlated to

1963;7:591–600. incisal and occlusal wear in an adult Swedish population. Acta

7. Reynolds JM. The organisation of occlusion for natural teeth. Odontol Scand. 1990;48:343–349.

J Prosthet Dent. 1971;26:56–67. 28. Poynter ME, Wright PS. Tooth wear and some factors

8. Schwartz H. Occlusal variations for reconstructing the natural influencing its severity. Rest Dent. 1990;6:8–11.

dentition. J Prosthet Dent. 1986;55:101–105. 29. Johansson A, Haraldson T, Omar R, Kiliaridis S, Carlsson GE.

9. Mann AW, Pankey LD. Concept of occlusion. The PM An investigation of some factors associated with occlusal tooth

philosophy of occlusal rehabilitation. Dent Clin N Am. wear in a selected high-wear sample. Scand J Dent Res.

1963;7:621–636. 1993;101:407–415.

10. Beyron H. Occlusal relation and mastication in Australian 30. Johansson A, Kiliaridis S, Haraldson T, Omar R, Carlsson GE.

aborigines. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:597–778. Covariation of some factors associated with occlusal tooth

11. D’Amico A. The canine teeth-normal functional relation of wear in a selected high-wear sample. Scand J Dent Res.

the natural teeth of man. J South Calif Dent Assoc. 1958;26: 1993;101:398–406.

6–23, 49–60, 127–142. 175–182. 194–208. 239–241. 31. Sadowsky C, BeGole EA. Long-term status of temporoman-

12. Scaife RR, Holt JE. Natural occurrence of cuspid guidance. dibular joint function and functional occlusion after ortho-

J Prosthet Dent. 1969;22:225–229. dontic treatment. Am J Orthodont. 1980;78:201–212.

13. Weinberg LA. A cinematic study of centric and eccentric 32. Madone G, Ingervall B. Stability of results and function of the

occlusions. J Prosthet Dent. 1964;14:290–293. masticatory system in patients treated with the Herren type of

14. Ingervall B, Hähner R, Kessi S. Pattern of tooth contacts in activator. Eur J Orthodont. 1984;6:92–106.

eccentric mandibular positions in young adults. J Prosthet 33. Sadowsky C, Polson AM. Temporomandibular disorder and

Dent. 1991;66:169–176. functional occlusion after orthodontic treatment: results of

15. Woda A, Vigneron P, Kay D. Non-functional and functional two long-term studies. Am J Orthodont. 1984;86:386–390.

occlusal contacts: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent.

1979;42:335–341.

16. Takai A, Nakano M, Bando E, Hewlett ER. Evaluation of three Correspondence: Dr Ahmad S. Al-Hiyasat, Department of Restorative

occlusal examination methods used to record tooth contacts in Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Jordan University of Science &

lateral excursive movements. J Prosthet Dent. 1993;70:500– Technology, P.O. Box 3030, Irbid, 22110, Jordan.

505. E-mail: hiyasat@just.edu.jo

ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 31; 628–633

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- INFERNO WORKOUTS SHRED-FinalDocument33 pagesINFERNO WORKOUTS SHRED-FinalAditya Sharan100% (6)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- QuestionDocument17 pagesQuestionHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Huge Freaky ForearmsDocument19 pagesHuge Freaky Forearms4040920100% (2)

- Clear Aligner Appliances by AlmuzianDocument4 pagesClear Aligner Appliances by AlmuzianHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Lower Labial Segment Crowding by AlmuzianDocument7 pagesLower Labial Segment Crowding by AlmuzianHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Jyothikiran TotalRecallDocument11 pagesJyothikiran TotalRecallHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- NatlJMaxillofacSurg22120-6243637 172036Document9 pagesNatlJMaxillofacSurg22120-6243637 172036HARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Syndrome: The Battered-ChildDocument8 pagesSyndrome: The Battered-ChildHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Sellke1998 PDFDocument9 pagesSellke1998 PDFHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Department of Orthodontics Sri Sankara Dental College Post Graduate Test - MODULE 1 A FEB-3-2-2018Document2 pagesDepartment of Orthodontics Sri Sankara Dental College Post Graduate Test - MODULE 1 A FEB-3-2-2018HARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Clear Aligner: Invisalign: A ReviewDocument3 pagesClear Aligner: Invisalign: A ReviewHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- If You Speak Very Good English Please Write Fluent': Ims Recruitment 1Document5 pagesIf You Speak Very Good English Please Write Fluent': Ims Recruitment 1HARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Syndromes of The First and Second Pharyngeal Arches: A ReviewDocument7 pagesSyndromes of The First and Second Pharyngeal Arches: A ReviewHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Randomized Control Trials in OrthodonticsDocument10 pagesAn Overview of Randomized Control Trials in OrthodonticsHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Instructions For The Conduct of Theory ExaminationsDocument1 pageInstructions For The Conduct of Theory ExaminationsHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- The Damon System - Simplifi Ed Mechanics: Written by Dr. Alan Bagden, D.M.DDocument8 pagesThe Damon System - Simplifi Ed Mechanics: Written by Dr. Alan Bagden, D.M.DHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Pdflib Plop: PDF Linearization, Optimization, Protection Page Inserted by Evaluation VersionDocument10 pagesPdflib Plop: PDF Linearization, Optimization, Protection Page Inserted by Evaluation VersionHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- MDS Rank List-June 2019 (2016 Admission)Document2 pagesMDS Rank List-June 2019 (2016 Admission)HARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Reviews: The Orthodontic Mini-Implant Clinical HandbookDocument1 pageReviews: The Orthodontic Mini-Implant Clinical HandbookHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- General and Oral Pathology, Microbiology and PharmacologyDocument4 pagesGeneral and Oral Pathology, Microbiology and PharmacologyHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Orthodontics in 3 Millennia. Chapter 15: Skeletal Anchorage: Special ArticleDocument4 pagesOrthodontics in 3 Millennia. Chapter 15: Skeletal Anchorage: Special ArticleHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Invisalign: Invisible Orthodontic Treatment-A ReviewDocument3 pagesInvisalign: Invisible Orthodontic Treatment-A ReviewHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Barry H. Grayson, Pradip R. ShetyeDocument7 pagesReview Article: Barry H. Grayson, Pradip R. ShetyeHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Lingual Orthodontics - A Review: Invited ArticlesDocument8 pagesLingual Orthodontics - A Review: Invited ArticlesHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Forces and Moments Generated With Various Incisor Intrusion Systems On Maxillary and Mandibular Anterior TeethDocument6 pagesForces and Moments Generated With Various Incisor Intrusion Systems On Maxillary and Mandibular Anterior TeethHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- MachadoDocument9 pagesMachadoHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Intrusion ArchesDocument7 pagesIntrusion ArchesHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Letters To The Editor: Rationale Behind Twin-Block InclineDocument1 pageLetters To The Editor: Rationale Behind Twin-Block InclineHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Horizontal and Vertical Resistance Strength of Infrazygomatic Mini-ImplantsDocument5 pagesHorizontal and Vertical Resistance Strength of Infrazygomatic Mini-ImplantsHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Harle-Sas 22 - Ponce, Kristel Mae O.Document11 pagesHarle-Sas 22 - Ponce, Kristel Mae O.Ponce Kristel Mae ONo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular QuestionDocument9 pagesCardiovascular Questionmedic99No ratings yet

- Peme Form B - Rev 20201020Document5 pagesPeme Form B - Rev 20201020Click TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Deep NeckSpaces 2002 04 SlidesDocument61 pagesDeep NeckSpaces 2002 04 SlidesIkhsan AmadeaNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Arthroscopy, Anatomy and Variants - Part 1Document6 pagesShoulder Arthroscopy, Anatomy and Variants - Part 1Raluca CostandacheNo ratings yet

- Cools. Scapular Mechanics and RehabilitationDocument9 pagesCools. Scapular Mechanics and RehabilitationWalter PelaezNo ratings yet

- Sesamoiditis and How Runners Can Treat or Prevent ItDocument9 pagesSesamoiditis and How Runners Can Treat or Prevent ItKunnel MathachanNo ratings yet

- VisibleBody - Types of Bones Ebook - 2018Document17 pagesVisibleBody - Types of Bones Ebook - 2018AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Ballista Routine Instructions PDFDocument2 pagesBallista Routine Instructions PDFAnibelka De Jesus CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Ammonicum CarbDocument7 pagesAmmonicum Carbgupta_ssrkm2747No ratings yet

- BSCI 4001 Transcript MidtermDocument4 pagesBSCI 4001 Transcript MidtermLynell Caraang BarayugaNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Warm-UpDocument10 pagesDynamic Warm-UpPrabhu ChandranNo ratings yet

- LRR ENT Part 2Document124 pagesLRR ENT Part 2pdivyashreerajNo ratings yet

- Brain StemDocument4 pagesBrain StemHeart Of Ayurveda Beatrice DNo ratings yet

- Mrishoulder 160528142230Document181 pagesMrishoulder 160528142230Risa Marissa100% (1)

- Chapter 12: The Back: Vertebral ColumnDocument7 pagesChapter 12: The Back: Vertebral ColumnJyrra NeriNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in NeuroanatomyDocument752 pagesLecture Notes in NeuroanatomyDenver NcubeNo ratings yet

- Cycling Strength & Conditioning Guide: Exercises Strength, Flexibility. MosleyDocument18 pagesCycling Strength & Conditioning Guide: Exercises Strength, Flexibility. MosleyJoseph GpNo ratings yet

- Ayurvedic Treatment of Cervical Disc BulgeDocument11 pagesAyurvedic Treatment of Cervical Disc BulgeParijatak AurvedaNo ratings yet

- 4.management of Vertical Discrepancies (2) 2Document97 pages4.management of Vertical Discrepancies (2) 2Arun Joy100% (2)

- Brief Note Tinnel SignDocument3 pagesBrief Note Tinnel SigncryystinaNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal System: Rizke, Najwa Abdelalim ADocument16 pagesMusculoskeletal System: Rizke, Najwa Abdelalim AChelo Jan GeronimoNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Electrophysiology and The Electrocardiogram - ClinicalkeyDocument40 pagesCardiac Electrophysiology and The Electrocardiogram - ClinicalkeyMelanie DascăluNo ratings yet

- OroAntral Communications and OroAntral Fistula PDFDocument22 pagesOroAntral Communications and OroAntral Fistula PDFAlejandro MejiaNo ratings yet

- Thoracic Cavity and Mediastinum: Anggraeni Janar WulanDocument36 pagesThoracic Cavity and Mediastinum: Anggraeni Janar WulanAfina HasnaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology Nails E-BookDocument22 pagesAnatomy and Physiology Nails E-BookdzemamejaNo ratings yet

- Surface MarkingDocument45 pagesSurface MarkingLucifer GNo ratings yet

- Tashia Individual Class AssessmentDocument78 pagesTashia Individual Class Assessmentapi-254739414No ratings yet