Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rhetoric and Persuasion Techniques

Uploaded by

xtheleOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rhetoric and Persuasion Techniques

Uploaded by

xtheleCopyright:

Available Formats

Rhetoric and Persuasion1

Webster’s dictionary gives this definition for rhetoric: “Rhetoric is the art of speaking or

writing effectively”. But we find this too general for our purposes here. One Classical

Greek formulation, from Aristotle, that does seem suitable, refers to rhetoric as “the

faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion”. This definition

refers to the importance of understanding the context in which we find ourselves, in

order to be able to know just how best to deal with its communication requirements. And

it refers to a very, very important quality in powerful communicators in business:

persuasiveness.

Effective informative messages, (i.e., messages the main point of which is to present

clear, concise information) will, in a sense, persuade our audience to engage with and

accept the information we want them to receive, and to act on it appropriately. Effective

bad-news messages end up persuading our audience to accept the bad news,

maintaining the necessary goodwill for a continued relationship (if that is what we want).

As effective communicators in this way, we persuade people of our credibility and our

general suitability to be conducting relationships with them. Our overall business

effectiveness is enhanced.

A large part of rhetorical effectiveness comes from understanding our situations and

contexts so well that we can find the most effective means of being persuasive in our

communication (or of sending informative messages that people can accept and will act

on, or bad-news messages that they will accept with goodwill). We will now discuss the

three main factors of any situation or context that we need to address rhetorically. They

are what Aristotle called the three rhetorical “appeals”, or “proofs”.

The three rhetorical appeals

In any situation or context within which we must communicate, there are three main

elements that we can focus on, as we try to find the best means of fulfilling our

objectives. They are the logic of the situation (logos), any emotion that may be present

within it (pathos), and our own place or role in it, our character and credibility (ethos).

Logos, or logic: In any situation there is always something about which we must be

“rational”; there are reasons for things, about which we can be “reasonable”. To

some degree, in any message, we must be logical, make good sense. But in some

situations, rigour, precision and comprehensiveness are essential. Appeals to

logos are necessary where facts or processes are of utmost importance. Scholarly

documents, reports of all kinds, and textbooks, are heavy on logos.

Pathos, or emotion: In any situation, there is an emotional dimension; there is always at

least some kind of subjective involvement. Some situations are relatively neutral,

while some are highly charged. Appeals to pathos work well where strong

emotions can be harnessed. They are vital in times of crisis, where emotions tend

to run high, and people are not thinking straight. Advertising works more on

people’s sense and subjectivity than on their logic and objectivity. Branding also

works like this.

Adapted from Wong, I., Connor, M. & Murfett, U. (2007). Business communication: Asian

1

Perspectives, Global Focus. Singapore: Pearson, Prentice Hall. 54-56.

Ethos, or character and credibility: In any situation we might be communicating in

different capacities; as a friend, a boss, a colleague, a professor, a student, a

client, an expert. Just how we represent ourselves in each of these capacities

reflects our character, and also our credibility. Aristotle maintained that ethos

depended on a person’s common sense (or intelligence), moral character, and

goodwill. An ethos driven message relies on the reputation or authority of the

sender. Leadership communication of all kinds is high in ethos, and politicians

rely on it a lot.

Sometimes, our contexts will demand that we Logos

approach our communicative task with one of

these dimensions as clearly the main one

(advertising soft drinks or perfume needs very

little logic, and the citing of support data in a

report needs no emotion quotient at all). But

usually, we are able to find some element of

each in every situation, and manage our actual

communication for the optimal mix of appeals.

Ethos Pathos

We can consider the appeals as existing in a

triangular relationship, each connected to the

other, to some extent.

Take this opening to an address, the general nature of which should be self-evident,

which engages all three, in equal measure, at the outset:

Friends, Staff and Management of this great company,

I know you must be very anxious, and some of you possibly angry, at the recent

developments in our merger with XXX. As your CEO, and as a veteran of 35 years

in this industry, I am here to address these matters, and hopefully put you more

at ease. Today, I shall outline the history of events, examine the current situation

in detail, and tell you what will happen in the future.

The first sentence after the salutation takes account of the audience’s possible emotional

state (appeal to pathos). The second refers to the speaker’s authority for speaking at all

on this matter and draws on what the audience knows of his or her character, in this way

establishing his or her credibility; thus it is a statement of ethos. (The salutation,

“friends” is also a statement of ethos, because it helps define a relationship between

speaker and audience.) The third sentence indicates to the audience just how the

elements of the situation will be related logically, in a reasonable manner, and is thus an

appeal to logos.

In this example, we can see all three dimensions reinforcing one another. That the

speaker addresses the audience’s emotions first tends to enhance his or her credibility,

and indicates a reasonable assessment of the situation (mergers and acquisitions usually

involve lots of emotion). Reminding the audience of his or her seniority and long

experience in the industry not only re-establishes his or her credibility, but makes him or

her the logical person to be making this address, and provides a sense of reassurance

and trust.

Logic, emotion, and character: three very important things that we need to be aware of

as we approach any communicative situation.

You might also like

- The Power of PersuasionDocument10 pagesThe Power of Persuasionthornapple25No ratings yet

- Effective communication as a key to success for managers: The art of convincing and winning over others to achieve one's goals.From EverandEffective communication as a key to success for managers: The art of convincing and winning over others to achieve one's goals.No ratings yet

- The Art of Convincing: How the skill of persuasion can help you develop your careerFrom EverandThe Art of Convincing: How the skill of persuasion can help you develop your careerNo ratings yet

- A General Summary of Aristotle RethoricDocument10 pagesA General Summary of Aristotle Rethoricharsapermata100% (1)

- Ethos, Pathos, and LogosDocument5 pagesEthos, Pathos, and LogosJuliana HoNo ratings yet

- Business Communication Management: The Key to Emotional IntelligenceFrom EverandBusiness Communication Management: The Key to Emotional IntelligenceNo ratings yet

- NGO301 - Nguyễn Thùy Dương - MA3-2019Document4 pagesNGO301 - Nguyễn Thùy Dương - MA3-2019Thuỳ DươngNo ratings yet

- Approaching A Forensic TextDocument10 pagesApproaching A Forensic TextKhadija SaeedNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Communication: A Quick Guide to Effective, Ethical InfluenceFrom EverandPersuasive Communication: A Quick Guide to Effective, Ethical InfluenceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Ethos Pathos LogosDocument8 pagesEthos Pathos LogosHafizul IdhamNo ratings yet

- Conflict management in 4 steps: Methods, strategies, essential techniques and operational approaches to managing and resolving conflict situationsFrom EverandConflict management in 4 steps: Methods, strategies, essential techniques and operational approaches to managing and resolving conflict situationsNo ratings yet

- Conversation Skills: How to Overcome Shyness, Initiate Small Talk, and Scale Your Communication SkillsFrom EverandConversation Skills: How to Overcome Shyness, Initiate Small Talk, and Scale Your Communication SkillsNo ratings yet

- HOW TO ANALYZE PEOPLE: Master the Art of Reading Minds, Understanding Behaviors, and Building Stronger Connections (2024 Guide)From EverandHOW TO ANALYZE PEOPLE: Master the Art of Reading Minds, Understanding Behaviors, and Building Stronger Connections (2024 Guide)No ratings yet

- Relationships for All: A Comprehensive Perspective on Gaining and Maintaining Better Communication for CompatibilityFrom EverandRelationships for All: A Comprehensive Perspective on Gaining and Maintaining Better Communication for CompatibilityNo ratings yet

- Empathy, Normalization and De-escalation: Management of the Agitated Patient in Emergency and Critical SituationsFrom EverandEmpathy, Normalization and De-escalation: Management of the Agitated Patient in Emergency and Critical SituationsMassimo BiondiNo ratings yet

- How to Speed Read People in Seconds: Learn How to Read, Analyze and Understand a Person's Body Signals like a PsychologistFrom EverandHow to Speed Read People in Seconds: Learn How to Read, Analyze and Understand a Person's Body Signals like a PsychologistNo ratings yet

- Transactional Analysis: A valuable tool for understanding yourself and othersFrom EverandTransactional Analysis: A valuable tool for understanding yourself and othersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Social Change Through Training and Education: Volume Iii— the 'Clothing' for Effective Policing: Cultural Competency, Spirituality and Ethics (Cultural Competency Self-Assessment Tool Included)From EverandSocial Change Through Training and Education: Volume Iii— the 'Clothing' for Effective Policing: Cultural Competency, Spirituality and Ethics (Cultural Competency Self-Assessment Tool Included)No ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document5 pagesChapter 3Amin HoushmandNo ratings yet

- Body Language: Body Language And Non-Verbal Communication: How To Detect Lies And Communicate Without Saying A WordFrom EverandBody Language: Body Language And Non-Verbal Communication: How To Detect Lies And Communicate Without Saying A WordNo ratings yet

- NM1101E Key Communication ConceptsDocument2 pagesNM1101E Key Communication ConceptsKunWeiTayNo ratings yet

- Definitions for Living: making sense of words and ideas that define our livesFrom EverandDefinitions for Living: making sense of words and ideas that define our livesNo ratings yet

- I Feel You: The Surprising Power of Extreme EmpathyFrom EverandI Feel You: The Surprising Power of Extreme EmpathyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- Rhetoric: From Persuasion to IdentificationDocument60 pagesRhetoric: From Persuasion to IdentificationMuhammed DamlujiNo ratings yet

- Argument, Rhetoric, and WritingDocument7 pagesArgument, Rhetoric, and WritingMaggie VZNo ratings yet

- Eloquence: Public Speaking Skills for Lawyers and Other ProfessionalsFrom EverandEloquence: Public Speaking Skills for Lawyers and Other ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- Ethos Logos Pathos: The Aristotle Way to PersuadeDocument4 pagesEthos Logos Pathos: The Aristotle Way to PersuadeairelliottNo ratings yet

- Little John and Face CommunicationDocument2 pagesLittle John and Face CommunicationFarel HakimNo ratings yet

- Rapport: The Art of Connecting with People and Building RelationshipsFrom EverandRapport: The Art of Connecting with People and Building RelationshipsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Art of Persuasive Communication: Influencing StakeholdersFrom EverandThe Art of Persuasive Communication: Influencing StakeholdersNo ratings yet

- Conversational Strategy HandoutDocument4 pagesConversational Strategy Handoutapi-361098001100% (1)

- Ethos, Pathos, Logos: Fundamental Factors of PersuasionDocument2 pagesEthos, Pathos, Logos: Fundamental Factors of PersuasionTanzy SNo ratings yet

- Ethos, Logos, PathosDocument3 pagesEthos, Logos, PathosZakaria LahrachNo ratings yet

- B1bffcommunication Patterns 1Document16 pagesB1bffcommunication Patterns 1Sana KhanNo ratings yet

- Relational Intelligence (2 books in 1): Relational Psychotherapy - How to Heal Trauma + From Relationship Trauma to Resilience and BalanceFrom EverandRelational Intelligence (2 books in 1): Relational Psychotherapy - How to Heal Trauma + From Relationship Trauma to Resilience and BalanceNo ratings yet

- Curs Dan StoicaDocument12 pagesCurs Dan StoicaAndreea HomoranuNo ratings yet

- The Art of Adaptive Communication: Build Positive Personal Connections with AnyoneFrom EverandThe Art of Adaptive Communication: Build Positive Personal Connections with AnyoneNo ratings yet

- The Nonverbal Factor: Exploring the Other Side of CommunicationFrom EverandThe Nonverbal Factor: Exploring the Other Side of CommunicationNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of Relationships: Unlocking Happiness Through Social ConnectionFrom EverandThe Psychology of Relationships: Unlocking Happiness Through Social ConnectionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Communication Theory ChapterDocument13 pagesCommunication Theory ChapterMia SamNo ratings yet

- Master Effective Business Communication SkillsDocument214 pagesMaster Effective Business Communication Skillsrajeshpavan92% (13)

- Business Communication NotesDocument214 pagesBusiness Communication NotesAnonymous xpdTqv100% (1)

- Systems engineering: understand each other to engineer togetherFrom EverandSystems engineering: understand each other to engineer togetherNo ratings yet

- Police Explorer Communication SkillsDocument18 pagesPolice Explorer Communication SkillsRama NathanNo ratings yet

- Love, Admiration and SafetyDocument18 pagesLove, Admiration and SafetyNancy Azanasía Karantzia90% (10)

- Integrative Clinical Social Work Practice: A Contemporary PerspectiveFrom EverandIntegrative Clinical Social Work Practice: A Contemporary PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Interpersonal Communication 1Document4 pagesRunning Head: Interpersonal Communication 1Taha OwaisNo ratings yet

- Travel Guard Direct Policy Wording On After 26 June 2021Document46 pagesTravel Guard Direct Policy Wording On After 26 June 2021xtheleNo ratings yet

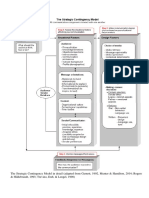

- The Strategic Contingency Model PDFDocument1 pageThe Strategic Contingency Model PDFxtheleNo ratings yet

- Signpost ExpressionsDocument1 pageSignpost ExpressionsxtheleNo ratings yet

- Travel Insurance Policy ContractDocument49 pagesTravel Insurance Policy ContractxtheleNo ratings yet

- The Strategic Contingency Model PDFDocument1 pageThe Strategic Contingency Model PDFxtheleNo ratings yet

- Class11-Revenue MGT - Before ClassDocument37 pagesClass11-Revenue MGT - Before ClassxtheleNo ratings yet

- Consent Form (Interview) Evidence Based Reflective Learning ReportDocument2 pagesConsent Form (Interview) Evidence Based Reflective Learning ReportxtheleNo ratings yet

- Consent Form (Interview) Evidence Based Reflective Learning Report PDFDocument2 pagesConsent Form (Interview) Evidence Based Reflective Learning Report PDFxtheleNo ratings yet

- Roaming SettingsDocument7 pagesRoaming SettingsxtheleNo ratings yet

- Time Series Predictive Models LectureDocument15 pagesTime Series Predictive Models LecturextheleNo ratings yet

- Functions of ManagementDocument3 pagesFunctions of ManagementxtheleNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Summary SlideDocument1 pageLesson 1 Summary SlidextheleNo ratings yet

- For Class Only Briefing On Individual Ethical Reasoning AssignmentDocument17 pagesFor Class Only Briefing On Individual Ethical Reasoning AssignmentxtheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Model Building TutorialDocument11 pagesAB1202 Model Building TutorialxtheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Statistics and AnalysisDocument18 pagesAB1202 Statistics and AnalysisxtheleNo ratings yet

- BE2601 Course Assessments GuideDocument24 pagesBE2601 Course Assessments GuidextheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Lect 06Document14 pagesAB1202 Lect 06xtheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Statistics and AnalysisDocument16 pagesAB1202 Statistics and AnalysisxtheleNo ratings yet

- Model Building and Selection TechniquesDocument20 pagesModel Building and Selection TechniquesxtheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Statistics and Analysis: (Part 1 of 2) Concepts of ProbabilityDocument17 pagesAB1202 Statistics and Analysis: (Part 1 of 2) Concepts of ProbabilityxtheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Statistics and Analysis: Sampling Distributions and Confidence IntervalsDocument15 pagesAB1202 Statistics and Analysis: Sampling Distributions and Confidence IntervalsxtheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Lect 05Document17 pagesAB1202 Lect 05xtheleNo ratings yet

- AB1202 Statistics and Analysis: (Part 1 of 2) Concepts of ProbabilityDocument17 pagesAB1202 Statistics and Analysis: (Part 1 of 2) Concepts of ProbabilityxtheleNo ratings yet

- Redes HetNetDocument2 pagesRedes HetNetVlaku AlejandroNo ratings yet

- Econometrics I: Professor William Greene Stern School of Business Department of EconomicsDocument47 pagesEconometrics I: Professor William Greene Stern School of Business Department of EconomicsAnonymous 1tv9MspNo ratings yet

- Fault Report SayausiDocument15 pagesFault Report SayausiDaniel Alejandro ZúñigaNo ratings yet

- NOS Lab - Viva 2Document37 pagesNOS Lab - Viva 2revathysrsNo ratings yet

- How To Motivate YourselfDocument4 pagesHow To Motivate YourselfAbialbon PaulNo ratings yet

- A Dramatic Interpretation of Plato's PhaedoDocument14 pagesA Dramatic Interpretation of Plato's PhaedoDiego GarciaNo ratings yet

- SAS Universal Viewer 1.2: User's GuideDocument32 pagesSAS Universal Viewer 1.2: User's GuideSmita AgrawalNo ratings yet

- 10 Meaningful Pros and Cons of Mandatory Military ServiceDocument4 pages10 Meaningful Pros and Cons of Mandatory Military ServiceJoseph LopezNo ratings yet

- Mobile Phones in the Classroom: Pros and ConsDocument11 pagesMobile Phones in the Classroom: Pros and ConsRohit AroraNo ratings yet

- Interactive Curve Design Using Digital French CurvesDocument8 pagesInteractive Curve Design Using Digital French CurveswupuweiNo ratings yet

- How to Apply for UST College Admission - Attach Photo, Signature, and FormsDocument3 pagesHow to Apply for UST College Admission - Attach Photo, Signature, and FormsCharles GunitaNo ratings yet

- Effective Human Relations Interpersonal and Organizational Applications 13th Edition Reece Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesEffective Human Relations Interpersonal and Organizational Applications 13th Edition Reece Solutions ManualDianaFloresfowc100% (49)

- CV3B EW1 Group5 Experiment2&3Document6 pagesCV3B EW1 Group5 Experiment2&3jml aguilarNo ratings yet

- Decimal FractionDocument15 pagesDecimal Fractionsathish14singhNo ratings yet

- Module 8Document7 pagesModule 8Maiden UretaNo ratings yet

- The PROJECT PERFECT White Paper CollectionDocument2 pagesThe PROJECT PERFECT White Paper CollectionBlackmousewhiteNo ratings yet

- Implementing Guidelines On Electronic Registration of Land Titles and DeedsDocument18 pagesImplementing Guidelines On Electronic Registration of Land Titles and DeedsSybil Salazar Vios100% (1)

- Wringinputih Village Attracts Local and Foreign TouristsDocument16 pagesWringinputih Village Attracts Local and Foreign TouristsBlegedez MetaohNo ratings yet

- CLVCD CL V Alpha: E387 (E387-Il)Document1 pageCLVCD CL V Alpha: E387 (E387-Il)FurqanNo ratings yet

- Distribution of Full Master Data Objects From C..Document5 pagesDistribution of Full Master Data Objects From C..raky0369No ratings yet

- Project AcknowledgementDocument2 pagesProject AcknowledgementTanzila Mulla100% (2)

- Rate of Respiration in Small InvertebratesDocument2 pagesRate of Respiration in Small InvertebratestahjsalmonNo ratings yet

- Assignment No.1Document5 pagesAssignment No.1Pheng TiosenNo ratings yet

- QPR - Technical Cleanliness (TC) RequirementsDocument12 pagesQPR - Technical Cleanliness (TC) RequirementsOliver SteinrötterNo ratings yet

- Topo ManualDocument10 pagesTopo ManualGrigoruta LiviuNo ratings yet

- What Does The Charter Document?: Get A Free Project Charter Template!Document10 pagesWhat Does The Charter Document?: Get A Free Project Charter Template!Marubadi SKNo ratings yet

- Level 1 Unit 10 TEDocument20 pagesLevel 1 Unit 10 TEjose luis gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Roland XP-60 PDFDocument36 pagesRoland XP-60 PDFeliasNo ratings yet

- Sociological Foundations of EducationDocument7 pagesSociological Foundations of EducationDxc Corrales100% (1)

- s3 Unit of Work - Maths - Volume and CapacityDocument5 pagess3 Unit of Work - Maths - Volume and Capacityapi-464819855No ratings yet