Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Pilot Study of A Kindergarten Summer School Reading Program in High-Poverty Urban Schools

Uploaded by

Yannu JiménezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Pilot Study of A Kindergarten Summer School Reading Program in High-Poverty Urban Schools

Uploaded by

Yannu JiménezCopyright:

Available Formats

A Pilot Study of a Abstract

Kindergarten Summer This pilot study examined an implementation of

a kindergarten summer school reading program

School Reading in 4 high-poverty urban schools. The program

targeted both basic reading skills and oral lan-

guage development. Students were randomly

Program in High- assigned to a treatment group (n ⫽ 25) or a

typical practice comparison group (n ⫽ 28)

Poverty Urban Schools within each school; however, randomization

was compromised due to school circumstances,

resulting in a quasi-experimental design. In-

struction was delivered by the schools’ regular

teachers during 20 full-day summer school ses-

Carolyn A. Denton sions. Each day treatment group students re-

Emily J. Solari ceived large-group listening comprehension

and vocabulary lessons anchored in storybook

Dennis J. Ciancio reading, along with small-group lessons focused

Steven A. Hecht on basic reading skills and listening comprehen-

sion. The intervention was associated with im-

Paul R. Swank proved outcomes for treatment group students

University of Texas Health Science Center at in word reading and listening comprehension

Houston with mixed results for phonemic awareness and

no significant between-group differences in

reading fluency or vocabulary. Such an ap-

proach is potentially efficacious, suggesting the

need for further research.

Although recent educational initiatives

have recognized the importance of early

reading instruction, there remains a dispar-

ity in reading achievement between stu-

dents from high- and low-income families.

According to results of the 2007 National

Assessment of Educational Progress report

(Lee, Grigg, & Donahue, 2007), only half of

U.S. fourth-grade students who are eligible

for the free or reduced-price lunch program

are able to read at or above a basic level and

only 17% of the students within this low

The Elementary School Journal socioeconomic group read proficiently. In

Volume 110, Number 4

© 2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

contrast, 79% of students ineligible for the

0013-5984/2010/11004-0001$10.00 free or reduced-price lunch program read

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

424 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

at or above the basic level and 44% of the effective when words are taught both di-

students within this higher socioeconomic rectly and indirectly through exposure in the

group are proficient readers. In the absence context of reading and listening, when stu-

of quality reading intervention, it is highly dents receive multiple exposures to vocabu-

likely that primary-grade students with lary words, and when students are actively

reading difficulties will experience contin- engaged in vocabulary instruction. Regard-

ued reading problems in the upper elemen- ing reading comprehension, the NRP recom-

tary and secondary grades (Francis, Shay- mended that instruction should guide stu-

witz, Stuebing, Shaywitz, & Fletcher, 1996; dents toward an awareness of their own

Juel, 1988; Torgesen & Burgess, 1998). Thus cognitive processes while reading (i.e., meta-

the failure to provide effective instruction cognitive processing). In order for many stu-

virtually guarantees continuing gaps in dents to learn to comprehend text, it is nec-

reading performance between students essary that teachers model and directly teach

with and without economic disadvantage. the practice of applying cognitive and meta-

cognitive comprehension strategies. In a ran-

domized experimental study, Solari and Ger-

Early Reading Instruction ber (2008) found that kindergarten students

The problem is daunting but not insur- who received direct instruction in vocabulary

mountable. There is converging research ev- words as well as strategies for comprehen-

idence that most young students at risk for sion of text that was read to them signifi-

reading difficulties can make adequate cantly outperformed their peers in listening

progress when provided with quality class- comprehension. Additionally, effects of the

room reading instruction along with short- vocabulary and listening comprehension in-

term supplemental intervention if needed tervention in kindergarten were detected in

(Mathes & Denton, 2002; Torgesen, 2000). first grade when treatment students outper-

This quality reading instruction in the pri- formed comparison students on a simple

mary grades addresses phonemic awareness, reading-comprehension task.

phonics, spelling, reading fluency, vocabu-

lary, and reading comprehension (Foorman

& Torgesen, 2001; National Reading Panel, Summer Learning

2000; Rayner, Foorman, Perfetti, Pesetsky, & Research has suggested that students

Seidenberg, 2001; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, who come from low-income families tend

1998). It is particularly important that young to lose ground during the summer months

students at risk for reading difficulties re- while those from middle- and high-income

ceive explicit instruction in phonological families are more likely to maintain the

awareness and phonics with ample opportu- knowledge and skills learned during the

nities to apply skills in connected text (Na- previous school year (Alexander, Entwisle,

tional Reading Panel [NRP], 2000; Snow et & Olson, 2001, 2007; Borman, Benson, &

al., 1998). In their synthesis of research, the Overman, 2005; Cooper, Nye, Charlton,

NRP found an effect size for phonics-based Lindsay, & Greathouse, 1996). For example,

interventions of 0.98 for struggling readers in Cooper et al. (1996) found that, on average,

kindergarten through second grade (Ehri, children from low-income backgrounds

Nunes, Stahl, & Willows, 2001). showed significant academic losses, ending

In addition to phonological processing, the summer about 3 months behind their

oral language proficiency has been found middle-class peers.

to be an important predictor of later read- Alexander and colleagues (2001, 2007)

ing ability (Bishop & Adams, 1990; Scarbor- had a different, but no less important find-

ough, 1989). The NRP (2000) findings indi- ing when they analyzed the progress made

cate that vocabulary instruction is most during the school year and summer break

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 425

by high-, middle-, and low-SES children, us- peers. Other authors have suggested that

ing longitudinal data collected from a ran- the quality of summer school programs

dom representative sample of students in tends to be higher in schools that serve

Baltimore. The researchers analyzed scores higher-income populations (e.g., Roderick,

on the reading-comprehension subtest of the Bryk, Jacob, Easton, & Allensworth, 1999).

California Achievement Test administered in Lauer et al. (2006) conducted a compre-

the fall and spring of grades 1–5, and again at hensive meta-analysis of the effects of read-

the end of grade 9, reporting a discrepancy ing and mathematics intervention provided

between scores of high- and low-SES chil- outside of the regular school day, both after

dren of 26.48 scale score points at the begin- school and during summer school. Only

ning of first grade. Between the fall and studies that included comparison groups

spring test administrations in grades 1–5 were included, but few had true experi-

(during the school year), this score difference mental designs. The majority were con-

was virtually unchanged, indicating that ducted with students who were either low-

schooling was effective in at least maintain- performing or from low-income families.

ing the reading levels of low-income students The researchers identified 30 studies with

relative to high-SES students. However, the reading outcomes published between 1986

gap widened to 48.48 points by the end of and 2003 that met their inclusionary crite-

grade 5 due to changes between the spring ria. Based on their analyses, Lauer and col-

and fall test administrations (i.e., over the leagues reported a mean effect size for out-

summer breaks). Interestingly, the results in- of-school reading interventions (combining

dicated that the high-SES group made signif- summer school and after school programs)

icant gains over the summer while the low- of .13, with somewhat larger effects (.22) for

SES group declined only slightly or remained studies involving students in the lower

unchanged. By the end of grade 9 there was elementary grades. The meta-analysis in-

a difference of 73.16 points between the cluded five studies that specifically exam-

scores of the high- and low-SES groups. ined the effects of summer school reading

intervention for students in kindergarten

through first grade, with widely varying

Effects of Summer School Programs effect sizes (ranging from ⫺.17 to .73).

Although common sense suggests that In an experimental study, Schacter and

summer school programs should be effec- Jo (2005) demonstrated the efficacy of a

tive in reducing summer learning losses or summer school reading intervention for

facilitating reading gains over the summer first-grade students at risk for reading dif-

break, existing research on the topic has ficulties. Students who were randomly as-

produced mixed results. There have been signed to an experimental condition partic-

few experimental or quasi-experimental ipated in a 2 hour reading program 5 days

studies in this area, leaving many unan- per week for 7 weeks. Instruction in both

swered questions regarding summer school word- and text-level reading skills was pro-

program effectiveness. Cooper, Charlton, vided in both whole-group and small-

Valentine, and Muhlenbruck (2000) per- group formats. The program consisted of

formed a meta-analysis of research on 93 40 minutes of small-group reading instruc-

summer school programs (with only a tion, 15 minutes of whole-group instruc-

small number of studies that had compari- tion, 15 minutes of independent phonics

son groups), finding average gains of one- practice, 10 minutes of paired reading us-

fifth of a standard deviation for participat- ing decodable text, 10 minutes of teacher

ing students. This review suggested that read-aloud, and 30 minutes of writing ac-

middle-class students benefited from sum- tivities. Results indicated significant differ-

mer school more than their lower-SES ences between the experimental and control

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

426 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

groups at posttest on measures of decoding district in the Southwest. The schools were

and comprehension. Furthermore, these all rated academically acceptable by the

gains were maintained at 3 months and at the state education agency. The average ethnic

end of the following academic school year. composition of the schools was 50% Afri-

This study was unique in that the interven- can American, 48% Hispanic, 1% white,

tion addressed both word-level and text-level and 1% Asian and other ethnicities. On av-

skills. Extant research suggests that summer erage, 95% of the students who attended

reading programs for at-risk populations the schools were classified as economically

tend to concentrate instructional time on disadvantaged.

word-level reading skills with less attention Schools 1 and 2 served students in pre-

to vocabulary and comprehension (Roderick kindergarten through fifth grade. Each of

et al., 1999). these schools had two kindergarten summer

school classrooms. In each school the teacher

in one classroom taught the experimental

Purpose of the Study reading program while the other teacher im-

Given the limited and contradictory re- plemented typical summer school instruc-

search base relative to summer school read- tion. School 3 served only early childhood

ing programs, as well as the continued through kindergarten and was paired with

prevalence of reading difficulties among School 4 which served only grades 1–5, be-

students from economically disadvantaged cause most of the students in School 3 would

backgrounds, there is a need for further attend School 4 when they entered first

research examining the efficacy of summer grade. In this study School 3 provided the

school reading intervention provided in the comparison classroom and School 4 pro-

early grades. The purpose of this pilot vided the experimental classroom. School 4

study was to examine the effects of an im- did not typically offer kindergarten summer

plementation of a kindergarten summer school but was piloting a model in which

school reading program that focused on kindergarten students who would be enter-

both word-level (i.e., phonemic awareness, ing the school as first graders would attend

phonics) and text-level (i.e., vocabulary, summer school at School 4 in order to be-

comprehension) skills in four high-poverty come acclimated to their new school. A fifth

urban schools. We addressed the following school that agreed to participate had to be

research question: Is participation in the dropped from the study because its kinder-

experimental summer school reading pro- garten summer school attendance was signif-

gram associated with better outcomes in icantly lower than expected and did not al-

word reading, phonemic awareness, vocab- low for the provision of both an experimental

ulary, listening comprehension, and oral and comparison classroom within the school.

reading fluency than participation in typi- Students. All students who attended

cal summer school instruction? We hypoth- English-only summer school classes in par-

esized that children who received the ex- ticipating schools were eligible to partici-

perimental reading program would have pate in the study, including those with

higher outcomes in each domain than those identified mild to moderate disabilities.

who received typical summer school in- Students were selected by their schools us-

struction. ing the schools’ normal procedures for de-

termining which students attend summer

school. Parents and guardians of these stu-

Method dents were informed of this decision by

Schools and Participants school personnel. In May, before the end of

This study was conducted in four ele- the regular school year, we randomly as-

mentary schools in a large urban school signed these students to the treatment or

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 427

comparison summer school classrooms and TABLE 1. Student Demographic Information by

Group

administered standardized pretests. Sum-

mer school instruction began during the Treatment Comparison

first week of June. (n ⫽ 25) (n ⫽ 28)

Summer school was also open to any Characteristics n % n %

student whose parents wanted them to at-

Ethnicity:

tend. Eight additional students who had African-American 21 84 19 68

not been selected by their schools enrolled Hispanic 2 8 8 28

in summer school after the term began. White 0 0 1 4

Asian and other 2 8 0 0

Since school personnel needed to immedi- Gender:

ately assign these children to a classroom, Male 16 64 7 25

they were asked to alternate the assignment Female 9 36 21 75

Economically

between the treatment and comparison disadvantaged:

classes within their schools and thus these Yes 23 92 25 89

students were not randomly assigned to No 1 4 2 7

Data unavailable 1 4 1 4

condition. We have reason to believe that

the schools did not strictly alternate be-

tween treatment and comparison class-

rooms when placing these students, but day of summer school at participating

tended to place students with lower read- schools and had some data (44 treatment,

ing performance in treatment classrooms. 48 comparison). Twenty-six of these stu-

For example, the mean pretest standard dents withdrew from summer school be-

scores on the Woodcock-Johnson Tests fore the end of the term, eight others had

of Achievement–III (WJ III; Woodcock, incomplete standardized test data for vari-

McGrew, & Mather, 2001) letter-word iden- ous reasons, and five were excluded be-

tification subtest for the treatment and cause the schools violated their randomiza-

comparison students who were placed by tion to condition. This left a final sample of

their schools were 105.25 (SD ⫽ 11.79) and 53 students (25 treatment, 28 comparison).

120.75 (SD ⫽ 8.58), respectively. Therefore, The mean age of treatment-group students

we characterize this pilot study as quasi- at posttest was 74.68 months (SD ⫽ 3.82),

experimental rather than experimental. In and the mean age of comparison-group stu-

addition, 10 students who had been ran- dents was 75.14 months (SD ⫽ 3.61). Table

domized to the comparison condition were 1 displays other demographic characteris-

moved by school personnel to the treat- tics, revealing gender differences between

ment classrooms without the researchers’ the groups (the treatment group was pre-

knowledge. We did not include the data dominantly male, while the comparison

from these students in our analyses. group was predominantly female).

In total, some assessment data were col- Teachers. Three teachers delivered the

lected for 147 students. For nearly all of experimental curriculum while three other

these students we collected standardized teachers delivered their typical summer

pretest data before the end of the regular school instruction. All of the participating

school year. Of the 147 students, 44 did not teachers were regular school district em-

attend summer school at all, leaving a sam- ployees selected by their schools to teach

ple of 103. Of these, 11 were dropped from summer school. During the previous school

the study because they attended the school year all of the teachers had taught kinder-

in which there were too few kindergarten garten except for one, who had taught first

summer school students to form treatment grade. Three noncertified paraprofessionals

and comparison classrooms, leaving a sam- also delivered small-group instruction in

ple of 92 students who attended at least one reading comprehension in the treatment

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

428 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

classrooms. The research team provided and supplies missing words. Split-half reli-

the treatment-group teachers and parapro- ability is .82–.85 in the age range of interest.

fessionals with 2 full days of professional For WJ III analyses we used W scores, a

development, periodic coaching support, continuously scaled standard score.

instructional materials, and fully devel- The CTOPP blending-words and sound-

oped lesson plans for implementing the matching subtests assess phonological

curriculum. awareness. The reliability of the CTOPP was

investigated using estimates of content sam-

pling, time sampling, and scorer differences.

Measures Most of the average internal consistency and

At pretest and posttest we administered alternate form reliability coefficients exceed

standardized assessments measuring pho- .80. The test/retest coefficients range from .70

nological awareness, word reading, text to .92. In the blending-words subtest the sub-

reading fluency, listening comprehension, ject is orally presented with isolated parts of

and vocabulary. In addition, we adminis- a word and is asked to put these parts to-

tered researcher-developed, curriculum- gether to make the whole word (e.g., t-r-a-p:

based measures (CBMs). All assessments trap). In the sound-matching subtest students

were individually administered to each select from pictures the one that represents a

participating child by a trained adult exam- word beginning or ending with the same

iner. Pretests were administered to most sound as a target word (e.g., Which word

students in May during the last 2 weeks of starts with the same sound as pan: pig, hat, or

the regular school year; students who came cone?). For CTOPP subtests we analyzed raw

to summer school after it had already be- scores because some students could not be

gun without having been previously iden- assigned standard scores at pretest due to

tified by their schools were pretested dur- very low raw scores.

ing the first week of summer school. Post- The TPRI oral reading fluency task is an

testing occurred for all children during the individually administered test of fluent and

last 3 days of the summer school session. accurate reading of connected text. Stu-

Standardized measures. The standard- dents’ fluency is evaluated with a timed

ized measures were (a) the WJ III (Woodcock 1-minute oral reading sample. The score is

et al., 2001) letter-word identification and oral the number of correctly read words per

comprehension subtests; (b) the Comp- minute. Researchers have consistently doc-

rehensive Test of Phonological Processing umented a moderate to strong positive re-

(CTOPP; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, lationship between oral reading fluency

1999) blending-words and sound-matching and reading comprehension for students in

subtests; (c) the Texas Primary Reading In- grades 1–5 (Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, & Jenkins,

ventory (TPRI; Foorman, Fletcher, & Francis, 2001). In the current study we administered

2004) oral reading fluency task; and (d) the the same TPRI story, which is approxi-

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test– 4 (PPVT-4; mately on a beginning-of-first-grade level,

Dunn & Dunn, 2007). at both pretest and posttest. Analyses uti-

The WJ III is a nationally standardized, lized raw scores.

individually administered achievement bat- The PPVT-4 is a well-established stan-

tery widely used in reading intervention dardized receptive vocabulary assessment

research. Letter-word identification as- in which students select from pictures the

sesses the ability to identify letters and read one that matches a word pronounced by

words presented in a list format. Split-half the tester. Split-half reliability is .93–.97 in

reliability is .98 –.99 in the age of interest. In the age range of interest. The PPVT-4 man-

the oral comprehension subtest the partici- ual recommends using growth scale value

pant listens to sentences or short passages (GSV) scores for measuring change in a

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 429

student’s vocabulary over time, stating that read-aloud session included planned interac-

the GSV measures “an examinee’s vocabu- tive comprehension instruction, while the af-

lary with respect to an absolute scale of ternoon session incorporated planned inter-

knowledge. As an examinee’s vocabulary active vocabulary instruction. Each of these

grows, the GSV will increase” (Dunn & sessions was followed by a set of small-group

Dunn, 2007, p. 21). rotations. During each rotation (in the morn-

Curriculum-based measures. The CBMs ing and again in the afternoon) small groups

were designed to assess mastery of con- of children rotated between two teaching ta-

cepts and skills taught in the treatment bles and two learning centers. Each group

classrooms. Pretest results on the CBMs spent 20 minutes at each of these four sta-

were used by teachers to guide their in- tions; every 20 minutes the teacher cued the

structional planning. The reading CBMs as- students to move to their next station. At one

sessed (a) identification of letter-sound teaching table, the teacher delivered basic

correspondences (30 items consisting of reading instruction during both the morning

upper- and lower-case letters; 15 letters that and afternoon rotations, while at the second

were taught in the research curriculum and teaching table the paraprofessional taught

15 untaught letters), (b) decodable word mathematics in the morning and reading

reading (25 three-letter words composed of comprehension in the afternoon. Each small-

letter-sounds taught in the research curric- group comprehension lesson focused on the

ulum), (c) high-frequency word reading (30 book that had been read aloud during the

items; 15 words students were taught in the days’ large-group sessions. Thus, every day

experimental curriculum and 15 untaught each child received a total of four 20-minute

words), and (d) identification of pictures small-group lessons (two basic reading, one

representing the vocabulary words that mathematics, and one reading comprehen-

were taught in the program (54 items). sion) at the teaching tables and worked at a

Each measure was untimed and individu- total of four learning centers. At one learning

ally administered. Raw scores consisted of center students independently completed a

the number of correct items. journal writing activity designed to reinforce

vocabulary that had recently been taught.

Other learning centers addressed reading

Procedures and math objectives and were planned by the

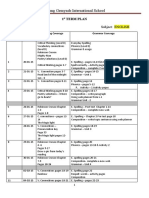

The summer school session lasted for 20 individual teachers. Figure 1 illustrates a

days in June and early July. Classes were sample daily schedule. Small-group sizes

held daily from 8:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. ranged from two to five students; most teach-

Treatment-group students attended an av- ers taught their most at-risk students in

erage of 18.24 days of summer school smaller groups and higher-performing stu-

(SD ⫽ 1.83); comparison-group students at- dents in larger groups.

tended an average of 18.54 days (SD ⫽ Contents of the reading program. The

1.60). Class sizes at the beginning of the experimental reading program was devel-

summer school session ranged from 11 to oped by the authors specifically for this study

16 in the treatment classrooms and 12 to 16 and is unpublished. Treatment-group stu-

in the comparison classrooms. dents received explicit, systematic instruction

The experimental reading intervention in phonemic awareness, phonics, recognition

was incorporated across the school day and of high-frequency words, and sentence read-

followed a consistent daily schedule. Each ing in the two basic reading lessons every

day teachers read the same picture book day. Teachers provided direct instruction in

aloud to the children during two 45-minute new phonics and phonemic awareness skills,

whole-group sessions: once in the morning and students practiced these skills through a

and again in the afternoon. The morning variety of hands-on activities with teacher

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

430 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

FIG. 1.—Sample daily schedule for summer school research curriculum

feedback. Emphasis was placed on teaching Vocabulary instruction occurred in a

students to blend sounds together to sound whole-group setting and through indepen-

out words and to map sounds to print to dent practice in the form of journal writing.

spell words phonetically (i.e., recognize The whole-group instruction consisted of a

sounds in spoken words and record these storybook read-aloud with integrated explicit

sound with letters). Students applied reading vocabulary instruction. Three new vocabu-

skills and strategies in brief decodable text. lary words were taught daily (words were

Listening comprehension instruction took preselected from the storybook text). Vocab-

place in both whole-group and small-group ulary instruction consisted of introducing the

formats. Whole-group comprehension in- words in the context of the storybook, pro-

struction consisted of a whole-book read- viding students with a short and easy-to-

aloud with discussion focused through guid- remember definition, teaching the meaning

ing questions written specifically for each of the words in new contexts or usages, and

book. Small-group instruction included ex- practicing word use orally and through writ-

plicit, direct instruction in three comprehen- ing and drawing pictures associated with the

sion skills: finding the main idea, summariz- words (at the journal-writing center).

ing, and sequencing. The length of material Fidelity of implementation. We col-

to be comprehended increased as students lected observational data to measure the

progressed within each of these skills. For fidelity with which teachers and parapro-

example, during the first few intervention fessionals implemented the experimental

sessions, concentrating on direct recall of program. Treatment-group teachers and

facts from text, students were presented with paraprofessionals were observed during in-

short sentences and asked to answer ques- struction using an observation instrument

tions related to facts in the sentences. Once that allowed for ratings of program adher-

students mastered this skill at the sentence ence, student on-task behavior, and instruc-

level, they moved onto multisentence pas- tional quality. Instructional quality for all

sages and finally to full paragraphs. intervention components was evaluated

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 431

using a three-point scale rating the teach- engaging students in using the words, and

ers’ provision of appropriate positive and (d) using the words in novel contexts and in

corrective feedback, lesson pacing, redirec- varied grammatical forms. These were in-

tion of off-task behavior, use of instruc- corporated into the program materials pro-

tional time, and warmth and enthusiasm vided to the treatment teachers and they

toward students (with a rating of 3 mean- achieved an average rating of 100% for

ing the behavior was observed for “most of these indicators. Their mean rating for stu-

the lesson,” 2 meaning “some of the les- dent on-task behavior was 98%, and the

son,” and 1 meaning “rarely”). We report mean quality rating was 96%.

fidelity as percentages, comparing each For the large-group comprehension com-

teacher’s ratings for each observation with ponent, treatment fidelity indicators included

a “perfect” rating on the instrument. (a) introducing the book to students in an

Each teacher was observed three times understandable way, (b) providing students

delivering basic reading instruction and with a problem/guiding question, (c) asking

two times delivering comprehension and appropriate questions to guide students to

vocabulary instruction. Each paraprofes- answer the problem/guiding question, (d)

sional was observed two times delivering engaging students in discussion of the key

small-group comprehension instruction. elements of the book, and (e) allowing stu-

Observations of basic reading were con- dents multiple opportunities to respond.

ducted by the first author, who was the Treatment-group teachers were provided

lead developer of that component. Obser- curriculum materials that included these ele-

vations of comprehension instruction were ments, and, on average, they achieved a rat-

conducted by the second author, the pri- ing of 99% for these indicators. The mean

mary developer of that component. Obser- rating for on-task behavior was 97% and the

vations of vocabulary instruction were con- mean quality rating was 95%. The nature of

ducted by a research assistant who had a the small-group comprehension instruction

primary role in the development of that was different in that it was more focused on

component. Since each component was ob- explicit instruction in comprehension skills,

served by only one person, interobserver and therefore fidelity of implementation was

reliability was not established. On some measured according to a different set of cri-

occasions, observations of basic reading teria: (a) presenting the lesson in a clear way,

skills, comprehension, and vocabulary may (b) modeling expected student behaviors

have been completed on the same day, but when needed, (c) providing students multi-

sometimes these were conducted on differ- ple opportunities to respond, (d) scaffolding

ent days. responses when necessary, and (e) providing

For the basic reading (decoding and appropriate corrective feedback. Paraprofes-

text reading) instructional component, pro- sionals in the treatment group achieved an

gram adherence was defined as implement- average rating of 96% for these behaviors

ing the lessons as they were described in during small-group instruction. The mean

the teacher’s manual, which was loosely on-task behavior rating was 98% and the

scripted. Treatment-group teachers had av- mean quality rating was 94%.

erage scores of 95% on program adherence, Comparison classroom instruction. Each

student on-task behavior, instructional comparison classroom teacher was observed

quality, and average overall fidelity. during one full reading lesson to verify the

For the vocabulary component, pro- nature of typical school practice. Following

gram adherence was defined as (a) provid- the observation, each teacher was asked

ing an understandable word definition or whether the observed lesson was typical of

explanation for each target word, (b) pro- their daily instruction, and all stated that this

viding explicit vocabulary instruction, (c) was the case. Observations indicated that in-

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

432 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

TABLE 2. Pretest and Posttest Observed Score Means and Standard Deviations; Cohen’s d Effect Sizes

Comparing Groups on Pretest-Posttest Difference Scores

Treatment (n ⫽ 25) Comparison (n ⫽ 28)

Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest

Measure M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) d

a

Letter-word ID 105.08 (11.62) 109.64 (11.86)* 106.89 (17.87) 106.46 (17.89) .91

Oral comprehensiona,d 98.08 (9.67) 100.75 (7.74)* 99.00 (11.67) 99.08 (10.46) .45

b

Blending words 11.56 (1.73) 13.16 (2.19)* 11.89 (2.66) 12.25 (2.73) .76

b

Sound matching 9.28 (2.23) 9.84 (2.34) 9.50 (1.99) 9.71 (2.67) .27

Oral reading fluencyc,e 27.10 (26.91) 32.10 (29.02) 35.88 (29.68) 43.73 (33.95) ⫺.28

Picture vocabularya,d 86.42 (8.91) 89.75 (7.62) 89.61 (10.67) 92.00 (7.84) .31

Letter-sounds CBMc,e 23.82 (4.65) 25.23 (2.93) 22.81 (6.84) 24.00 (6.79) .10

High-frequency CBMc,e 17.05 (10.52) 23.36 (7.74)* 19.12 (10.88) 21.73 (10.62) .81

Decodable-words CBMc,e 10.73 (8.09) 19.55 (6.71) 13.77 (9.87) 17.77 (8.75) .76

Vocabulary CBMc,e 36.82 (4.93) 42.00 (5.89) 37.50 (5.23) 41.69 (6.11) .30

NOTE.—Letter-word ID ⫽ Letter-word identification; CBM ⫽ curriculum-based measure.

a

Standard scores reported.

b

Scale scores reported.

c

Raw scores reported.

d

Treatment group n ⫽ 25; comparison group n ⫽ 26.

e

Treatment group n ⫽ 22; comparison group n ⫽ 26.

*p ⬍ .05, one tailed.

struction in comparison classrooms differed aloud to the students. Little direct instruc-

from that in the treatment classrooms on im- tion was observed in this classroom.

portant dimensions. All observed lessons, ex- We observed no formal vocabulary in-

cept for a few minutes in one classroom struction in comparison-group classrooms.

when students worked in learning centers, On very few occasions teachers paused

were implemented in whole-class formats. while reading aloud to students to provide

The comparison-group teachers were a quick explanation of a word, but this ac-

observed implementing a variety of activi- tivity did not meet the criteria described

ties. In the first classroom, the teacher im- above for the treatment condition. Simi-

plemented a published summer school cur- larly, we did not observe purposeful in-

riculum, including phonological awareness struction focused on comprehension. Refer-

and worksheet activities as well as individ- ences to comprehension took place during

ual text reading. Students in this classroom whole-group lessons when the teacher read

were mostly on task during instruction, a book to or with the students and asked

which included explicit modeling of the them for predictions related to the book.

use of analogies to known words to help However, we did not observe a book read-

spell unknown words. No direct instruc- aloud session for one of the three compar-

tion was observed in the second classroom; ison teachers, and it is possible that she

students recited poems and sang songs re- may have provided contextualized vocab-

lated to alphabetic knowledge, after which ulary or comprehension instruction during

the teacher read a book aloud to the class. such a read-aloud format.

In the third classroom students participated

in chants and songs related to alphabetic

knowledge for a portion of the class, fol- Results

lowed by an activity related to word read- Descriptive statistics for all pretest and

ing and spelling and another activity in posttest measures by treatment condition

which volunteers read sentences. The les- can be found in Table 2. For the WJ III

son concluded with the teacher reading subtests, analyses were performed using W

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 433

TABLE 3. Posttest Effects for Pretest, Intervention Group, and Teacher on Standardized Measures

WJ III Letter-Word WJ III Oral

Identification Comprehension CTOPP Blending Words

Source df F p df F p df F p

Pretest 1, 46 283.98 ⬍.0001 1, 44 16.63 .0001 1, 46 41.70 ⬍.0001

Group 1, 46 5.71 .011 1, 44 2.83 .049 1, 46 3.54 .033

Teacher 4, 46 3.04 .013 4, 44 .83 .257 4, 46 2.27 .038

Peabody Picture

CTOPP Sound Matching TPRI Oral Reading Fluency Vocabulary

df F p df F p df F p

Pretest 1, 46 33.84 ⬍.0001 1, 40 289.63 ⬍.0001 1, 44 90.88 ⬍.0001

Group 1, 46 .015 .350 1, 40 .29 .295 1, 44 .38 .269

Teacher 4, 46 .099 .210 4, 40 .59 .338 4, 44 .26 .451

NOTE.—P-values reflect one-tailed tests of significance.

scores, but we report pre-post standard the standardized measures are presented in

scores in Table 2 to enable comparison to Table 3.

other studies. Similarly, the PPVT analyses Preliminary data investigations in-

were performed using GSV scores and the cluded analyses of pretest equivalence and

CTOPP analyses were conducted on raw examination of outliers, potential depar-

scores, but we report pre-post standard tures from normality, and homogeneity of

score descriptive statistics for ease of inter- variance. Simple ANOVA indicated no sig-

pretation. Oral Reading Fluency analyses nificant between-group differences on pre-

were performed and results reported using test scores on any variable; however, we

raw scores reflecting the number of words included pretest in our analyses because of

read correctly per minute. For this pilot its significant contribution to outcomes on

study, we were interested in estimating the all variables. We also included teacher as a

effects of the intervention on students’ fixed effect in our models to account for the

growth over the 4-week period; we calcu- effects of individual teachers beyond those

lated Cohen’s d effect sizes comparing the of treatment-group assignment. As our hy-

treatment and comparison groups on their pothesis was unidirectional and the inter-

pre-post difference scores for each variable. vention was not expected to result in wors-

Effect sizes ranged from small (on growth

ening performance, we conducted one-

in sound matching, PPVT, and the letter-

tailed tests of significance. Moreover, in a

sound CBM) to large (on growth in blend-

pilot test, for which the goal is not evaluat-

ing words and all measures of word read-

ing the efficacy of an intervention but de-

ing) favoring the treatment group. The

termining whether a randomized trial is

effect on growth in oral comprehension

warranted, we judged that type II error was

was moderate. Only one effect size favored

more serious than type I error.

the comparison group, a small effect on

oral reading fluency. Several of the distributions were found

to violate the assumption of homogeneity

of variance and some were also found to

Standardized Measures depart significantly from the normal distri-

First we report the results for standard- bution. The problem of heterogeneous vari-

ized measures, followed by the results for ances in analysis of variance (ANOVA) can

the researcher-created CBMs. Results for be handled in one of several ways. One way

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

434 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

is to use a nonparametric ANOVA such as Von Mises, p ⫽ .2289; Anderson-Darling, p ⬎

the Kruskal-Wallis test, but this limits one to .15) were not. However, two outliers were

simple analyses. Since in this case we needed evident in the comparison group (precisely

to control for pretest levels on the measures the same as evident in the PPVT distribu-

and teacher effects, the nonparametric ap- tion). From pretest to posttest, these two stu-

proach was not appropriate. An alternative dents lost 29 and 36 standard score points,

method involves using a mixed-models anal- indicating likely testing error. If these stu-

ysis to model the variance separately. Using dents’ data are eliminated, the results do not

this model results in a log-likelihood statistic change appreciably, except that there is no

that can then be compared to the log likeli- longer any hint of nonnormality; there are

hood for a model assuming equal variances. still differences in variances and the group

Twice the difference in the log likelihoods is effect is significant (F(1, 44) ⫽ 2.83, p ⫽ .0498,

approximately distributed as chi-square and one-tailed). The teacher effect was not signif-

can be used to test the homogeneity assump- icant for this variable, but the pretest effect

tion as well. This method allows us to include was. After the outliers were dropped, the ef-

other terms in the model, such as pretests fect size for the difference score on this vari-

and teacher effects, and thereby provides a able was in the medium range (d ⫽ .45).

reasonable solution to the case of heteroge- For CTOPP analyses, we utilized raw

neous variance across groups in our data. scores since some students scored too low at

Thus, for each outcome we ran an initial pretest to be assigned standard scores. For

model that included the pretest assessment, CTOPP sound matching, there was no indi-

treatment-group assignment, and teacher cation of heterogeneous variances or of non-

(nested within group) as predictors of the normality in the data. The model, however,

posttest allowing for the variances to be dif- did not show any group or teacher effects,

ferent across groups. A second model was only that of the pretest. For CTOPP blending

then run that kept all the predictors in the words, there was no indication of heteroge-

model but restricted the variance to be held neous variances nor of nonnormality in the

constant across groups. The log-likelihood residuals, but the group effect was significant

differences were then tested to see which (F(1, 46) ⫽ 3.54, p ⫽ .033, one-tailed) over and

model was more appropriate for the data. above the effect of the pretest and that of

The residuals for each model were also ob- teacher nested within group. The effect size

tained and tested for normality, as this is the for the difference score in blending words

actual assumption for such models. was in the large range (d ⫽ .76).

For WJ III letter-word identification there For TPRI oral reading fluency, the vari-

was no indication of heterogeneous variances ances again appeared to be different

or nonnormality. Controlling for the pretest (2(1) ⫽ 6.90, p ⬍ .01) and the residual dis-

and teachers nested within group, the result tribution was determined to be nonnormal

for treatment group was significant (F(1, on all tests (Shapiro-Wilks, p ⫽ .0094). The

46) ⫽ 5.71, p ⫽ .0106, one-tailed). The effect data did not fit the pattern that might have

size for letter-word identification difference allowed a generalized model, so we ap-

scores was large (d ⫽ .91). plied a square-root transformation, which

For WJ III oral comprehension, the data removed the significant nonnormality.

indicated that the group variances were dif- However, this model did not demonstrate

ferent (2(1) ⫽ 18.1, p ⬍ .01). Regardless, the any significant group effects.

group differences were also significant (F(1, For the PPVT-4 GSV score, there was a

46) ⫽ 3.25, p ⫽ .039, one tailed). Normality significant difference in the models assum-

was borderline as one test (Shapiro-Wilks) ing equal versus unequal variances (2(1) ⫽

was significant ( p ⫽ .043), but the other three 18.1, p ⬍ .01). In addition, the residuals for

(i.e., Kolmogorov-Smirnov, p ⬎ .15; Cramer- this model showed a marked skewness

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 435

TABLE 4. Posttest Effects for Pretest Errors, Intervention Group, and Teacher on Curriculum-Based Measures

High-Frequency- Decodable-Words

Letter-Sound CBM Words CBM CBM Vocabulary CBM

Source df F p df F p df F p df F p

Pretest 1, 41 82.11 ⬍.0001 1, 41 149.18 ⬍.0001 1, 41 50.08 ⬍.0001 1, 41 102.49 ⬍.0001

Group 1, 41 1.74 .097 1, 41 2.98 .046 1, 41 1.85 .090 1, 41 .44 .256

Teacher 4, 41 2.36 .035 4, 41 1.46 .116 4, 41 1.83 .071 4, 41 .38 .412

NOTE.—P-values reflect one-tailed tests of significance.

which was reflected in a significant lack of words (F(1, 41) ⫽ 2.98, p ⫽ .046, one-tailed).

normality detected by the Shapiro-Wilks The effects of pretest were significant for all

test ( p ⬍ .0001). However, the results were variables, and effects for teacher were sig-

primarily due to two cases, both in the nificant for letter-sounds. No effects be-

comparison group, who were substantially yond those of pretest were evident for de-

different at posttest compared to pre, but in codable words or vocabulary.

the opposite from the expected direction.

These were the same two cases with outli- Discussion

ers in the WJ III oral comprehension distri-

The purpose of this pilot study was to exam-

bution. One showed a PPVT standard score

ine the potential efficacy of a kindergarten

decline of 57 points over 4 weeks, while the

summer school reading intervention for

other lost 21 standard score points. Drop-

students attending high-poverty schools in

ping these two cases from the analysis re-

order to determine whether further ex-

moved the significant nonnormality from

perimental research of the intervention

the residual distribution; however, this did

approach was warranted. Through a quasi-

not affect the results, which showed that

experimental design, outcomes in phonemic

the pretest GSV score was related to post-

awareness, word reading, text reading flu-

test but neither teacher effects nor group

ency, listening comprehension, and vocabu-

effects were statistically significant.

lary were investigated to determine if a brief,

intensive summer school reading program

Curriculum-Based Measures could be associated with positive effects on

Since the CBMs were untimed and con- student outcomes. Results indicated that stu-

sisted of items normally taught in kinder- dents who attended the intensive summer

garten and first grade, they had the poten- reading program made significantly better

tial for ceiling effects, which were evident gains on measures of word reading and lis-

in the distributions. Therefore, using the tening comprehension when compared to

GLIMMIX procedure in SAS, we analyzed students who received typical summer

probabilities of the error frequencies on school instruction, although word reading

each measure based on a Poisson distribu- outcomes could also be attributed in part to

tion. Again, we accounted for pretest and differences between teachers. Results related

teacher effects in evaluating between- to phonological awareness were mixed, and

group effects. Table 4 presents the results. there were no significant between-group dif-

Although the treatment group made ferences detected in oral reading fluency or

larger mean gains than the comparison vocabulary. These findings are encouraging,

group on all CBMs, significant between- especially considering that past research sug-

group differences were detected in only gests that the gap in academic performance

one of the four measures after accounting between students who come from low-

for teacher and pretest: high-frequency income and higher-income backgrounds

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

436 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

tends to widen during the summer months word reading and listening comprehension

(Borman et al., 2005; Cooper et al., 1996). development are aligned with those of

The most robust effect size was associ- Schacter and Jo (2005), who found positive

ated with growth in word reading as mea- effects for a summer school program de-

sured by the WJ III. Treatment-group stu- livered to children in kindergarten and first

dents also performed significantly better grade when instruction addressed both

than comparison-group students in high- word- and text-level reading skills. For

frequency word recognition. Although stu- young students at risk for reading difficulties,

dents in the treatment classrooms outper- particularly those from low-income back-

formed comparison students in reading grounds who possibly have more limited op-

decodable words, this difference was not portunities to build wide background knowl-

statistically significant after accounting for edge, it may be particularly important to

teacher-level effects. These results are en- provide instruction in listening comprehen-

couraging, as learning to read words accu- sion in addition to word-level reading in-

rately and fluently is an essential goal of struction. More research directly examining

early reading instruction. Although some this question is warranted.

children in the treatment classrooms re- In the area of phonemic awareness, the

mained at risk for reading failure at the end treatment group had significantly better

of summer school, the instruction they re- outcomes in phoneme blending, but not in

ceived in phonics and word recognition sound matching. Nonetheless, the positive

may have created a foundation to support outcome for phoneme blending may be im-

their progress in decoding in first grade. portant. The ability to segment words into

Students’ growth in listening comprehen- smaller parts (i.e., onsets and rimes, pho-

sion in this study is also noteworthy. The nemes) and blend word parts together to

relationship between listening and reading form words has been shown to be strongly

comprehension is strong; students’ ability to related to early reading development (e.g.,

comprehend written text is similar to their Stahl & Murray, 1994), and deficits in this

comprehension of the text when it is spoken domain have been reliably associated with

(Bell & Perfetti, 1994; Gernsbacher, Varner, reading difficulties and disabilities (e.g.,

& Faust, 1990). This relationship has been Fletcher, Lyon, Fuchs, & Barnes, 2007; Vel-

confirmed by studies that demonstrate a sig- lutino, Fletcher, Snowling, & Scanlon,

nificant predictive relationship between lis- 2004). Although the treatment group had

tening comprehension and reading compre- more standard score growth than the com-

hension (Aarnoutse, van den Bous, & Brand- parison group on sound matching, the dif-

Gruwel, 1998; Garner & Bochna, 2004; Nation ference was not statistically significant. Ob-

& Snowling, 2004). Moreover, research indi- servations in comparison classrooms

cates that listening comprehension may be a indicated that these students practiced re-

precursor target skill that could be useful citing and singing rhyming poems and

for identifying students at risk for reading- songs, and direct instruction in phonologi-

comprehension failure (Carlisle & Felbinger, cal awareness was observed in one class-

1991; Catts & Hogan, 2003; Duke, Pressley, & room. This instruction may have been suf-

Hilden, 2004). The approach to comprehen- ficient to promote growth in identifying

sion instruction implemented in the current initial sounds in words.

study was also found to be efficacious in a As beginning readers learn to recognize

previous study of listening comprehension many words orally at sight and quickly de-

instruction delivered to English language code unknown words, their reading becomes

learners in kindergarten (Solari & Gerber, more fluent (Ehri, 2005). Although between-

2008) and appears to merit further study. group differences in oral reading fluency

The findings of this study in terms of were not statistically significant, comparison-

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 437

group students made greater gains than tion in each condition limited our ability to

treatment-group students on this variable. distinguish between the effects of the inter-

Future implementation of the intervention vention and the effects of assignment to

may include more practice reading con- particular teachers. Also related to the

nected text to develop the automaticity asso- small sample size is our high attrition rate;

ciated with fluent reading (Chard, Vaughn, & many of the students we had pretested and

Tyler, 2002). assigned to the treatment or comparison

There is evidence that vocabulary devel- conditions at the end of the regular school

opment can be promoted in young children year did not attend summer school and

when teachers use an interactional read- were subsequently unavailable for assess-

aloud style and extended book discussion to ment, while several others left before the

decontextualize language (e.g., Dickinson & end of the summer school term and thus

Smith, 1993), and other research has demon- lacked posttest data. Equally important, the

strated significant effects for approaches to randomization of students to classrooms

vocabulary instruction similar to the one im- was compromised by the schools. These

plemented in the current study (e.g., Elley, factors may have biased our results, al-

1989; Wasik & Bond, 2001). However, stu- though schools’ apparently nonrandom

dents who attended the treatment classrooms placement of newly arriving students into

did not differ significantly from comparison- classrooms probably resulted in a more

group students on the PPVT-4 or on the challenging test of the intervention since

vocabulary CBM. This may be due to the students placed in treatment classrooms

short duration of summer school; however, were more impaired than those placed in

even with a short-term intervention, one comparison classrooms. However, the vio-

would expect some differential movement of lation of randomization limits the general-

treatment-group students on the CBM of vo- izability of our results. Other limitations

cabulary words that were specifically taught related to study implementation are (a) the

in the program. The relatively high perfor- experimental condition incorporated small-

mance of both groups at pretest on the group instruction provided by paraprofes-

vocabulary CBM suggests that the lack of sionals, while paraprofessionals were not

differences could be due to the fact that available to the comparison-group teach-

many children in both groups already ers, and (b) interrater reliability for class-

knew the meanings of the instructed room observations was not established

words. An alternative explanation is that since only one person observed each inter-

the research curriculum introduced words vention component (i.e., one person ob-

at too quick a pace (three new words per served basic reading instruction, another

day) and that students were unable to use observed comprehension, and a third ob-

the words to the extent necessary to de- served vocabulary) and only one person

velop an understanding of them and re- observed in the comparison classrooms.

member their meanings. Both possibilities

should be considered prior to beginning an

efficacy study of this intervention. Implications for Research and Practice

In spite of these limitations, this pilot

study demonstrates that larger-scale exper-

Limitations of the Pilot Study imental research of similar interventions is

The results of this pilot study are not warranted. Summer school provides edu-

necessarily generalizable to other student cators with an important opportunity to

populations. The study was limited by its provide instruction that may have positive

small sample size. In particular, the fact effects on reading outcomes for students

that only three teachers provided instruc- from low-income families. As it is currently

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

438 THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOURNAL

implemented, summer school instruction Catts, H. W., & Hogan, T. P. (2003). Language

offered to primary-grade students often basis of reading disabilities and implications

for early identification and remediation.

consists of low-intensity activities that are

Reading Psychology, 24, 223–246.

not guided by clear instructional objectives. Chard, D. J., Vaughn, S., & Tyler, B. (2002). A

Often, summer school programs fail to uti- synthesis of research on effective interven-

lize research-based curricular programs tions for building reading fluency with ele-

(Heyns, 1987; Roderick et al., 1999). Requir- mentary students with learning disabilities.

ing kindergarten and first-grade students Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35, 386 – 406.

Cooper, H., Charlton, K., Valentine, J. C., & Mu-

who are at risk for reading difficulties to hlenbruck, L. (2000). Making the most of

attend summer school and using that time summer school: A meta-analytic and narra-

to provide instruction similar to that pro- tive review. Monographs of the Society for Re-

vided in this study may help narrow the search in Child Development, 65, 1–130.

persistent gap in reading outcomes be- Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J., &

Greathouse, S. (1996). The effects of summer

tween children from low- and higher- vacation on achievement scores: A narrative

income backgrounds. This question merits and meta-analytic review. Review of Educa-

further empirical study. tional Research, 66, 227–268.

Dickinson, D. K., & Smith, M. W. (1993). Long-

Note term effects of preschool teachers’ book

readings on low-income children’s vocabu-

lary and story comprehension. Reading Re-

Correspondence concerning this article search Quarterly, 29, 104 –123.

should be addressed to Carolyn Denton, Chil- Duke, N. K., Pressley, M., & Hilden, K. (2004).

dren’s Learning Institute, 7000 Fannin St., UCT Difficulties with reading comprehension. In

2443, Houston, TX 77030. E-mail: Carolyn. C. A. Stone, R. Stillman, B. J. Ehren, & K.

A.Denton@uth.tmc.edu. Apel (Eds.), Handbook of language and literacy

(pp. 501–520). New York: Guildford.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody

References

Picture Vocabulary Test (4th ed.). Minneapo-

lis: Pearson Assessments.

Aarnoutse, C. A. J., van den Bos, K. P., & Brand- Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: The-

Gruwel, S. (1998). Effects of listening com- ory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of

prehension training on listening and read- Reading, 9, 167–188.

ing. Journal of Special Education, 32, 115–126. Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Stahl, S. A., & Willows,

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., & Olson, L. S. D. M. (2001). Systematic phonics instruction

(2001). Schools, achievement, and inequal- helps students learn to read: Evidence from

ity: A seasonal perspective. Educational Eval- the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis.

uation and Policy Analysis, 23(2), 171–191. Review of Educational Research, 71(3), 393– 447.

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., & Olson, L. S. Elley, W. B. (1989). Vocabulary acquisition from

(2007). Lasting consequences of the summer listening to stories. Reading Research Quar-

learning gap. American Sociological Review, terly, 24, 174 –187.

72, 167–180. Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Fuchs, L. S., & Barnes,

Bell, L. C., & Perfetti, C. A. (1994). Reading skill: M. A. (2007). Learning disabilities: From identifi-

Some adult comparisons. Journal of Educa- cation to intervention. New York: Guildford.

tional Psychology, 86, 244 –255. Foorman, B. R., Fletcher, J. M., & Francis, D. J.

Bishop, D. V., & Adams, C. (1990). A prospective (2004). Early reading assessment. In W. Ev-

study of the relationship between specific ers & H. J. Walberg (Eds.). Testing student

language impairment, phonological disor- learning, evaluating teaching effectiveness (pp.

der and reading retardation. Journal of Child 81–125). Stanford, CA: Hoover Press.

Psychology and Psychiatry, 31(7), 1027–1050. Foorman, B. R., & Torgesen, J. K. (2001). Critical

Borman, G. D., Benson, J., & Overman, L. T. elements of classroom and small-group in-

(2005). Families, schools, and summer learn- struction promote reading success in all chil-

ing. Elementary School Journal, 106, 131–150. dren. Learning Disabilities Research and Prac-

Carlisle, J. F., & Felbinger, L. (1991). Profiles in tice, 16(4), 202–211.

listening and reading comprehension. Jour- Francis, D. J., Shaywitz, S. E., Stuebing, K. K.,

nal of Educational Research, 84, 345–354. Shaywitz, B. A., & Fletcher, J. M. (1996). De-

JUNE 2010

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SUMMER SCHOOL READING PILOT 439

velopmental lag versus deficit models of & Allensworth, E. (1999). Ending social promo-

reading disability: A longitudinal, individ- tion: Results from the first two years. Chicago:

ual growth curves analysis. Journal of Educa- Consortium on Chicago Public Schools.

tional Psychology, 88, 3–17. Scarborough, H. S. (1989). Prediction of reading

Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, disability from familial and individual dif-

J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indi- ferences. Journal of Educational Psychology,

cator of reading competence: A theoretical, 81(1), 101–108.

empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Schacter, J., & Jo, B. (2005). Learning when school

Studies of Reading, 5, 239 –256. is not in session: A reading summer day-camp

Garner, J. K., & Bochna, C. R. (2004). Transfer of intervention to improve the achievement of

a listening comprehension strategy to inde- exiting first-grade students who are economi-

pendent reading in first-grade students. cally disadvantaged. Journal of Research in

Early Childhood Education Journal, 32, 69 –74. Reading, 28(2), 158 –169.

Gernsbacher, M. A., Varner, K. R., & Faust, M. E. Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (Eds.).

(1990). Investigating differences in general (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young

comprehension skill. Journal of Experimental children. Washington, DC: National Acad-

Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, emy Press.

16, 430 – 445. Solari, E. J., & Gerber, M. M. (2008). Early com-

Heyns, B. (1987). Schooling and cognitive devel- prehension instruction for Spanish-speaking

opment: Is there a season for learning? Child English language learners: Teaching text-

Development, 58, 151–160. level reading skills while maintaining effects

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A on word-level skills. Learning Disabilities Re-

longitudinal study of 54 children from first search and Practice, 23(4), 155–168.

through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Stahl, S. A., & Murray, B. A. (1994). Defining

Psychology, 80, 437– 447. phonological awareness and its relationship

Lauer, P. A., Akiba, M., Wilkerson, S. B., Apthorp, to early reading. Journal of Educational Psy-

H. S., Snow, D., & Martin-Glenn, M. L. (2006). chology, 86, 221–234.

Out-of-school-time programs: A meta-analysis Torgesen, J. K. (2000). Individual differences in

of effects for at-risk students. Review of Educa- response to early interventions in reading:

tional Research, 76, 275–313. The lingering problem of treatment resisters.

Lee, J., Grigg, W., & Donahue, P. (2007). The Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 15,

nation’s report card: Reading 2007 (NCES 55– 64.

2007-496). Washington, DC: National Center Torgesen, J. K., & Burgess, S. R. (1998). Consis-

for Education Statistics, Institute of Educa- tency of reading-related phonological pro-

tion Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. cesses throughout early childhood: Evidence

Retrieved March 10, 2009, from http:// from longitudinal-correlational and instruc-

nationsreportcard.gov tional studies. In J. Metsala & L. Ehri (Eds.),

Mathes, P. G., & Denton, C. A. (2002). The preven- Word recognition in beginning reading (pp.

tion and identification of reading disability. 161–188). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 9(3), 185–191. Vellutino, F. R., Fletcher, J. M., Snowling, M. J.,

Nation, K., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Beyond & Scanlon, D. M. (2004). Specific reading

phonological skills: Broader language skills disability (dyslexia): What have we learned

contribute to the development of reading. in the past four decades? Journal of Child

Journal of Reading, 27, 342–356. Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 2– 40.

National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., & Rashotte, C. A.

to read: An evidence-based assessment of the sci- (1999). Comprehensive test of phonological pro-

entific research literature on reading and its im- cessing. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

plications for reading instruction. Washington, Wasik, B. A., & Bond, M. A. (2001). Beyond the

DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pages of a book: Interactive book reading

Rayner, K., Foorman, B. R., Perfetti, C. A., Pe- and language development in preschool

setsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2001). How classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology,

psychological science informs the teaching 93, 243–250.

of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Woodcock, R. W., McGrew, K. S., & Mather, N.

Interest, 2, 31–74. (2001). Woodcock-Johnson III tests of achieve-

Roderick, M., Bryk, A. S., Jacob, B. A., Easton, J. Q., ment. Itasca, IL: Riverside.

This content downloaded from 207.162.240.147 on July 24, 2016 14:02:16 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Extra Practice For Struggling Readers - High Frequency WordsDocument80 pagesExtra Practice For Struggling Readers - High Frequency WordsNosan Alo100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Our World 2E AmE Starter Lesson Planner LoResDocument87 pagesOur World 2E AmE Starter Lesson Planner LoResLuzma AHNo ratings yet

- English 3 TG Quarter 4Document100 pagesEnglish 3 TG Quarter 4almera malik67% (3)

- My Phonics Grade 1 Teacher BookDocument95 pagesMy Phonics Grade 1 Teacher BookTrần Khoa Nguyên100% (2)

- Sli and SlaDocument15 pagesSli and SlaYannu JiménezNo ratings yet

- Do Working Memory Deficits Underlie Reading Problems in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ?Document14 pagesDo Working Memory Deficits Underlie Reading Problems in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ?Yannu JiménezNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Speed Theories of Cognitive Development: Increasing The Rate of Recall Without Affecting AccuracyDocument7 pagesRethinking Speed Theories of Cognitive Development: Increasing The Rate of Recall Without Affecting AccuracyYannu JiménezNo ratings yet

- A Serial Position Effect in Recall of United States PresidentsDocument4 pagesA Serial Position Effect in Recall of United States PresidentsYannu JiménezNo ratings yet

- Society For Research in Child Development, Wiley Child DevelopmentDocument8 pagesSociety For Research in Child Development, Wiley Child DevelopmentYannu JiménezNo ratings yet

- Action Research PowerpointDocument16 pagesAction Research Powerpointapi-297838790No ratings yet

- Boyer Kate ResumeDocument2 pagesBoyer Kate Resumeapi-661434263No ratings yet

- Decodable Words and SentencesDocument30 pagesDecodable Words and SentencesmarychakkourNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Ela Progress ReportDocument5 pagesKindergarten Ela Progress Reportapi-259778858100% (1)

- SNC Catalogue NewDocument66 pagesSNC Catalogue NewHASSAAN UMMENo ratings yet

- GoalsDocument3 pagesGoalsapi-595567391No ratings yet

- Studyladder - Orange Spelling Program - Overview and Recording Sheet (29 Page PDF)Document29 pagesStudyladder - Orange Spelling Program - Overview and Recording Sheet (29 Page PDF)Jayanthi LoganathanNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Primary Curriculum Doha British School WakraDocument7 pagesOverview of The Primary Curriculum Doha British School WakraParaskevi AlexopoulouNo ratings yet

- Common Core State Standards For English Language Arts Grade 5Document10 pagesCommon Core State Standards For English Language Arts Grade 5Chym LimeNo ratings yet

- LND Kitaabcha Final-V7 0Document61 pagesLND Kitaabcha Final-V7 0KHANNo ratings yet

- Primary Year 1 SK Scheme of WorkDocument382 pagesPrimary Year 1 SK Scheme of WorkElmi MellieNo ratings yet

- Today We Discussed AboutDocument108 pagesToday We Discussed AboutKaye UyvicoNo ratings yet

- English Teacher Guidebook Year 2Document330 pagesEnglish Teacher Guidebook Year 2Azlan Ahmad100% (2)