Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oxfordhb 9780199686476 e 30 PDF

Uploaded by

CatalinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oxfordhb 9780199686476 e 30 PDF

Uploaded by

CatalinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Oxford Handbooks Online

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity,

power, and economy

Salima Ikram

The Oxford Handbook of Zooarchaeology

Edited by Umberto Albarella, Mauro Rizzetto, Hannah Russ, Kim Vickers, and Sarah Viner-

Daniels

Print Publication Date: Mar 2017

Subject: Archaeology, Scientific Archaeology, Environmental Archaeology, Egyptian

Archaeology

Online Publication Date: Apr 2017 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199686476.013.30

Abstract and Keywords

In addition to providing food, companionship, and raw materials for clothing, furniture,

tools, and ornaments, animals also played a key role in religious practices in ancient

Egypt. Apart from serving as sacrifices, each god had one or more animal as a totem.

Certain specially marked exemplars of these species were revered as manifestations of

that god that enjoyed all the privileges of being a deity during their lifetime and which

were mummified and buried with pomp upon their death. Other animals, which did not

bear the distinguishing marks, were mummified and offered to the gods, transmitting the

prayers of devotees directly to their divinities. These number in the millions and were a

significant feature of Egyptian religious belief and self-identity in the later periods of

Egyptian history.

Keywords: Egypt, mummy, deity, sacred animal, votive offerings, ibis, dog, Theban tombs

Introduction

ANIMALS play an important part in religious rituals throughout the world. This was no

more so than in ancient Egypt and Nubia, where animals were vital to religious practices.

The most obvious and significant feature of Egyptian religion was that most divinities

were theriomorphic, either completely or partially (Fig. 29.1), and that specific living

animals, such as the Apis Bull, were, during their lifetime, revered as manifestations of

particular deities on earth, with oracular powers (Kessler, 1986; Ikram, 2015a). Upon

their death, these sacred animals were prepared for burial and interred with great pomp.

Page 1 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

In addition to being potential manifestations of gods, animals also served deities. The

flight of birds was used to celebrate certain festivals (Kessler and Nur el-Din, 2015: 128–

9) and possibly for divination (Murnane, 1980: 37). Animals provided the raw materials,

such as hides, shell, fur, guts, bones, ivory, and feathers, used to fabricate a variety of

objects including amulets, regalia, furniture, and musical instruments for use in temple

cults, as well as in private religious life. The foundation of temples and tombs was also

sanctified through animal sacrifice, with bucrania and forelimbs of cattle deposited at the

buildings’ corners (Weinstein, 1973). Bucrania were also used in the external adornment

of early Egyptian tombs (Emery, 1949; 1954; 1958; 1974), as well as playing a part in

Nubian burials (Grant, 1991; Chaix and Grant, 1992; Davis, 2008; Ikram, 2012) as

manifestations of wealth, offerings to the deceased, and for protection. Funerary

offerings included meat and poultry, as attested both by texts and funerary (p. 453)

remains, which sustained the deceased throughout eternity (Barta, 1963; Ikram, 1995;

2009; 2011; 2012).

Living animals played a

crucial role in temple cult,

and by extension, the

Egyptian economy. There

were hundreds of animals,

primarily cattle (Bos

taurus) and birds (for

example Anas spp., Anser

spp., and Columba spp.),

although sheep (Ovis

ammon f. aries) and goat

(Capra aegagrus f. hircus)

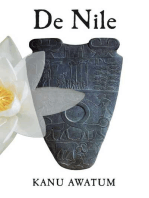

Figure 29.1 The raptor-headed god Horus, also feature in offering

associated with solar worship and divine kingship,

and the crocodile headed god Sobek, also a solarlists and were sacrificed

deity, as well as a fertility god, from Kom Omboon a daily basis as

temple, near where mummified raptors and

offerings in temples

crocodiles were found.

throughout Egypt. After

Author’s own image.

consecration, much of this

meat was redistributed as

payment to temple personnel, who then either consumed it or used it for barter, thus

making such offerings a significant component of the economic engine of Egypt (Posener-

Kriéger, 1976; Ikram, 1995; Lehner, 2000; Warburton, 2000; Posener-Kriéger et al., 2006;

Rossel, 2007). Huge herds of cattle, goats, and sheep had to be purpose-raised for this,

with the temples having enormous holdings of livestock (Ghoneim, 1977).

Offerings did not only take the form of food; in later Pharaonic history, during the seventh

century BC through the third century AD (Late and Graeco-Roman periods), a curious new

type of animal offering came into prominence, associated with the formal sacred animal

cults: votive animal mummies (Ikram and Iskander, 2002; Ikram, 2015a). (p. 454)

Page 2 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Studying animal use in religious contexts binds together many diverse strands of inquiry,

allowing one to investigate the relationships between Ancient Egyptian society and

culture and its fauna. These include:

• the human impact on the environment and ecology of an area;

• animal husbandry/management of animal resources;

• a study of society and social change;

• forms of ethnic identity and acculturation;

• cultural contacts;

• manifestation of political power;

• the economy and the role of trade within it;

• and religious constructs.

This brief essay focuses on the animal cults that reached their apogee in Late and

Graeco-Roman Egypt, and the implications that these had for the relationship between

humans and animals.

Animal Cults

The Romans derided the Egyptians for their reverence of animals (Smelik and Hemelrijk,

1984), with Juvenal writing in his Satires (XV) ‘Who has not heard, Volusius, of the

monstrous deities those crazy Egyptians worship? One lot adores crocodiles, another

worships the snake-gorged ibis … you’ll find whole cities devoted to cats, or to river-fish

or dogs …’ (Juvenal Satires 15.1, Rudd trans., 1991). For the Egyptians, however, animals

seemed to be endowed with supernatural powers and gifts, with intimate access to the

gods, and these attributes, together with their ‘otherness’, provided the basis for many

Egyptian religious beliefs that linked specific animals to certain deities that shared their

attributes and strengths (Dunand et al., 2005; Ikram, 2015a). Most gods had at least one

totemic animal that exemplified his or her attributes, and often the heads of these

animals were shown on human bodies as manifestations of the gods (Fig. 29.1). Thus, cats

were identified with Bastet, goddess of love, beauty, and self-indulgence—all

characteristics seen in living cats. Dogs and other canines were associated with Anubis,

god of cemeteries, embalming, and travel, because these creatures frequented

embalming houses (no doubt lured by the scent of flesh) and cemeteries, and were adept

at navigating the desert. Raptors were associated with the sun god as they flew high into

the sky, able to see even the smallest creature from their lofty height, as well as due to

their coloration, and the way in which their eyes are evocative of the sun. The sacred ibis

was an avatar of Thoth, the god of writing and wisdom, no doubt because the beak of the

ibis took the form of a reed pen, and the bird was seen bent over, ever questing with its

beak, in search of some truth—or at least a true lunch! However, despite their

associations with divinities, the Egyptians did not worship all cats, dogs, and birds,

although acknowledging their link with the gods. (p. 455)

Page 3 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Certainly, animals played a prominent role in religion in Egypt by the second century AD,

when Juvenal knew the country, but the employment of living and dead creatures had not

always been manifested as he saw them. Until about the seventh century BC, animal cults

were limited in scope, with single sacred animals, recognized by special markings, being

revered as the avatar of a particular deity at a particular location. It was believed that

each god could manifest him- or herself in that specific creature during its lifetime, and

after its death the spirit of the god would move to a different animal of its species,

recognizable by identical markings, a concept not dissimilar to the manifestation of the

Dalai and other Tibetan lamas. Upon their death, such animals were, at least from the

middle of the New Kingdom (fourteenth century BC), elaborately mummified and buried

in catacombs with considerable splendour (Kessler, 1986; Ray, 2001; Ikram, 2015a).

Examples of sacred animal interments survive in the bull cemeteries at Saqqara,

Heliopolis, and Armant, and of the rams at Elephantine. It was only from the seventh

century AD onward that the cult of the living animals became widespread, as previously

such cults seem to have been limited to only a few sites: Memphis/Saqqara, Heliopolis,

and Thebes and its environs. It is at this time that large-scale votive mummies started to

be offered to the animal manifestations of divinities, with cults appearing all over the

country, from Alexandria to Aswan, as well as in the oases of the Western Desert (Fig.

29.2). Individual pilgrims apparently purchased mummies of animals associated with a

particular deity, and dedicated it to its corresponding divinity so that the donor’s prayers

would reach the god through the medium of the deities’ own animal. It may be that

animal mummies, perhaps because they had once been alive, were deemed more effective

intercessors than offerings of a statue or stela, and once transformed by mummification

into a semi-divine state, they could interact eternally with the gods.

Thus far, there is no incontrovertible explanation as to why this era saw a massive

expansion of animals employed in cults. No doubt a variety of factors fed into this

phenomenon. Perhaps primarily, this was a manifestation of the uniqueness of Egyptian

religion and a way of separating and defining Egyptians from other ethnic groups. The

26th Dynasty (c.664–525 BC) was a time when Egypt was recovering from foreign rule

(first Nubian, then Assyrian) and struggling to re-establish its independence and reassert

its former greatness. As a result, the rulers (probably in conjunction with the higher-

ranking priesthood) consciously established a culture that hearkened back to times when

Egypt was great. Archaism is apparent in art, literature, rhetoric, and modes of

presenting the king and the gods. Religion was also key to uniting the country and

reasserting the domination of kings and priests. It is probable that animal cults and votive

mummies were a major part of this propagandistic programme, creating a unique way in

which people could engage with the gods, recalling the earliest times of Egyptian history

when the animal aspects of deities were emphasized. These cults, with their animal votive

offerings, provided a more accessible route to the more important deities of the Egyptian

pantheon, such as the sun god, who had hitherto been the preserve of rulers rather than

the populace. Texts found inside catacombs suggest that a greater number of people had

direct contact with these gods than with the deities who resided as statues within a

temple (Kessler and Nur el-Din, 2015; Ray, 2011; 2013; Smith et al., 2011). (p. 456) (p. 457)

Page 4 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

This ‘democratization’ of religion allowed for a more intimate relationship between

people and gods, particularly as access to the living animal deities was more possible

than access to the images of gods that were kept in close seclusion within a temple. No

doubt this accessibility was significantly responsible for the success of these cults.

Subsequently, when the

Persians seized Egypt in

525 BC, animal cults

united the Egyptians and

provided a very distinct

way for them to define

themselves religiously as

separate from the Persians

—an aspect of this cult

that persisted through the

Roman domination. The

Macedonian dynasties

(332–30 BC) seem to have

embraced animal cults

(Dodson, 2015; Kessler and

Nur el-Din, 2015), which

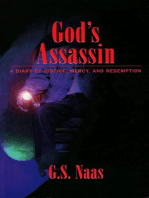

Figure 29.2 A map showing the major animal

mummy cemeteries and sacred sites in Egypt. were extremely active

Drawing by N. Warner. during this time. The

popularity of the cults also

served to support the associated temples and local shrines, which burgeoned during this

time, seemingly serving an increasing number of cities and towns throughout the country,

as can be seen by the proliferation of sites that contain animal mummies (Fig. 29.2). As

the temples and the rulers were allied (albeit in an uneasy alliance at times), it was in

their interest to maintain and encourage popular cults that ultimately benefited the state,

forming part of the economic (and social) web between state, temple, and the people. In

the Roman period the practice continued, but with less state support; however, it

maintained a way for Egyptians, and those who embraced their religion (Smelik and

Hemelrijk, 1984), to forge and maintain a distinct and separate identity for themselves,

and maybe even created a power-base from which to defy, in a small way, their

conquerors periodically.

The Votive Mummies

Although sacred animals were buried throughout the course of Egyptian history, it is the

votive mummies that make up the majority of animal mummies that are found in

museums today, as well as excavated in catacombs and other tombs throughout the Nile

Valley and the oases of the Western Desert. The number of species represented in these

cults of the Late Period onward include almost all animals, with the notable exceptions of

hippopotami and donkeys, both of which were associated with Seth, an inimical god in

charge of deserts, among other things (Wilkinson, 2003: 197–9). Thus, cats, dogs, foxes,

Page 5 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

jackals, mongooses, sheep, goats, gazelles, shrews, monkeys, rodents, snakes, crocodiles,

lizards, fish, raptors, ibises, other birds, scarab beetles, and even their dung balls are

offered to various deities (Lortet and Gaillard, 1903–1909; Daressy and Gaillard, 1905;

Kessler, 1986; Ikram and Iskander, 2002).

What is most striking about these mummies is their vast number. Unfortunately, it is only

recently that a systematic approach to the study of animal mummies from excavations has

been established, thus it is difficult to calculate the number of mummies that might have

existed in each catacomb. However, some estimates are available. The Catacomb of

Anubis at Saqqara contained some 7.8 million canine mummies (Ikram et al., 2013); five

hundred canines were identified at el-Deir (Dunand et al., 2015); the Ibis Galleries at

Saqqara yielded at least 4 million ibises (Ray, 1976); well over 1.8 million ibises were

offered in Tuna el-Gebel (von den Driesch et al., 2005; Kessler and (p. 458) Nur el-Din,

2015); more than five thousand ibises were discovered at Abydos (Loat, 1914; Ikram,

personal observation); in a single chamber of a much larger burial complex associated

with Theban Tomb (TT) 12, ten thousand ibises and two thousand raptors were identified

(Ikram et al., in prep.); more than six hundred monkeys of different sorts were found at

Tuna el-Gebel (Kessler and Nur el-Din, 2015); and at least one thousand cat mummies

were recovered from the Bubasteion at Saqqara (A. Zivie, personal communication); at

Tebtunis in the Fayum a deposit of ten thousand crocodiles is estimated (Bagnani, 1952).

These figures represent a small proportion of the votive animal mummy deposits found

throughout Egypt (Table 29.1), and do not, save for the estimates for the Catacomb of

Anubis and the chamber in TT 12, provide an accurate estimate for the total number of

animals in any single catacomb. If one were to be able to calculate the true number of

votive animal mummies from all the known cemeteries in Egypt, the number for each

species would be well into the millions.

Table 29.1 Table showing the MNI of votive mummies from diverse cemeteries dating

from c.600 BC to c. AD 300

Species Site MNI

Canine Saqqara 7,800,000

Canine el-Deir 500

Ibis diverse cemeteries 5,815,000

Baboons Tuna el-Gebel 600+

Raptors Thebes TT 12 2,000

Cats Saqqara 1,000+

Page 6 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Crocodiles Tebtunis 10,000+

Implications of the Production of Votive Mummies

Clearly, the huge amount of mummification materials needed to produce millions of

mummies had a marked impact on the economy, both national and international (Ikram,

2015a: 16–43). Natron, the prime ingredient in mummification, used to desiccate and de-

fat, came from two places in Egypt: the Wadi Natrun and el-Kab. This had to be processed

and transported in vast quantities throughout the country in order to carry out basic

mummification; at least 400 kg of natron are necessary to properly mummify a sheep

(Ikram, 2015b); thus a single dog would need c.200 kg, while smaller creatures would

require less. Oils (lettuce, castor, sesame) were locally produced, but resins for anointing

the animals were imported from the Levant and East Africa as well as, possibly, Arabia. At

least thousands of kilometres of linen had to be used for wrapping (p. 459) the animals,

though these were locally available, and were often reused. More striking, though, is the

sheer number of animals that were mummified. These had to play a major role in the

economy, particularly providing revenue for temples and their dependents.

All the animals offered as ex-votos were indigenous to Egypt, save for baboons. Although

once native, by the seventh century BC they were long extinct within Egypt, having

retreated further south, and thus had to be imported for cult purposes. Quite possibly

attempts at breeding them took place, but there is no evidence for a successful breeding

programme. Osteological evidence from the extensively studied baboon mummies from

Tuna el-Gebel (von den Driesch and Boessneck, 1985; von den Driesch, 1993; Nerlich et

al., 1993) and from Saqqara (Goudsmit and Brandon-Jones, 2000), indicate that many of

the animals showed pathologies indicative of ill health, some due to being kept in

constrained spaces and poor diet, which most scholars think is due to the time the

animals spent in the temple areas. Indeed, poor living conditions and care by people who

were unversed in what these animals needed to survive and thrive might have been

largely responsible for their condition, but responsibility for this did not lie solely with the

care-takers associated with the temples. The long journey from sub-Saharan and northern

East Africa, often taking months, even in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when

camels were commonly used (Walz, 1978), necessitated that the animals be kept in

confined spaces, most probably with a restricted and often insufficient diet. Thus, these

creatures probably arrived, at great expense, in Egypt, already malnourished and prone

to disease. Perhaps this is one reason why breeding groups could not be established

successfully, thereby accounting for the limited number of baboon mummies in

comparison with those of animals that were indigenous.

Given their number, the native animals must have been bred for the purpose as it was

impractical to think of trapping so many animals, particularly those that could be easily

bred, such as ibises, dogs, and cats. It is more likely that creatures such as raptors were

trapped, although they too could be bred in captivity, albeit less effectively than the other

Page 7 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

animals. Indeed, if all these animals had been trapped and killed, rather than reared

especially for their fate, it quite likely would have resulted in the extinction of these

species (Ikram et al., 2015). The vast number of animals in the catacombs is not the only

argument to support the idea of breeding programmes to supply the cult. Eggs (Lortet

and Gaillard, 1903–1909; Ray, 1976; Bresciani, 2015; Ikram, personal observation from

Sharuna, Thebes, and Abydos), particularly of ibises, feature amongst the votive

offerings, with crocodile hatcheries being posited in association with temples dedicated

to the crocodile god, Sobek (Bresciani, 2015).

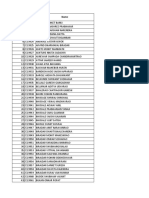

Furthermore, the number of immature individuals found in animal cemeteries is

remarkable, and argues for breeding programmes. In the Galleries of the Catacombs of

Anubis at Saqqara 75% of the number of identified specimens (NISP) of 6,034 bones

belonged to immature animals (Ikram et al., 2013) (Fig. 29.3). At el-Deir, out of five

hundred individuals, 25% were puppies between 1 and 2 months of age, and 36% were

juveniles between 6 and 14 months (Dunand et al., 2015). (p. 460)

(p. 461)

At TT 12, a subterranean

chamber measuring 9 m2

was filled with the remains

of disarticulated and

somewhat-burnt bird

Figure 29.3 Distribution of the ages at death of the mummies. In order to

dogs from the Catacombs of Anubis at Saqqara. sample the remains, a

Prepared by L. Bertini. four-litre container was

filled with bones chosen

from three of the nine square metre contexts; the sample was taken at random, and was

examined in detail. The samples were scooped up by hand and thus some anatomical

elements escaped inclusion as we did not want to dig down too violently and grasp the

bones too firmly lest they break. Each sample was analysed to obtain an overall idea of

species represented, minimum number of birds placed in the room, their ages, and

whether entire birds had been mummified or just specific portions. Information recorded

also included pathologies, anatomical element and portion thereof, side, approximate age,

and degree of burning. In addition, ‘cherry-picked’ bones (those not belonging to ibises)

from the sieved remains of the chamber, extraneous to the four litre samples, were also

analysed with a view to gaining a better perspective of the non-sacred ibis remains that

were given as offerings. This yielded a total of 3,867 bones. Of these, a total of 756

immature/juvenile bones were noted, about 20% of the total number of bones. It is

difficult to differentiate species in bones belonging to such young birds (including

fledglings), but the general impression is that at least six hundred of these bones were

from ibises, while the rest were of raptors (Ikram et al., in prep.). Although neither

numbers nor percentages are currently available from the other ibis catacombs, it is

likely that a large percentage of young or even eggs comprised their population.

Page 8 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

The amount of disease and trauma found on the dog bones from the Anubis Catacomb

also argues for their being kept in confined spaces (breeding pens) and not being well

looked after. Out of the 3,867 bones examined, 266 of the canid bones (c.5%) showed

evidence of pathology (Ikram et al., 2013). Another canine cemetery at Saqqara also

yielded evidence for dogs being housed in a closely confined space, and poorly fed and

looked after (Hartley et al., 2011).

It would seem that the puppies found in these cemeteries had been deliberately killed to

supply the demand for animal mummies (Ikram et al., 2013; Dunand et al., 2015), as has

been found in the case of kitten mummies recovered from similar catacombs at Saqqara

and elsewhere (Armitage and Clutton-Brock, 1980; 1981; Charron, 1990; Zivie and

Lichtenberg, 2015). Other votive animals probably also were deliberately killed in order

to meet the demand of the thousands of pilgrims who required them. Quite possibly birds

such as ibises had their necks broken (strangled), although this is difficult to determine

due to the twisted position of the necks necessitated by the way in which they were

wrapped. Some young crocodiles with dented skulls appear to have been killed by blows

to the head, while it has been posited that others were dispatched by the slitting of their

nostrils (E. Bresciani, personal communication; Bresciani, 2015).

Clearly, animals such as dogs and cats were being farmed in dedicated spaces in order to

support the temples and their pilgrims (Ikram et al., 2013). Such large-scale animal

farming might well have extended beyond the immediate confines of temple personnel,

and be part of the larger village/town/city economy, or even include a wider regional

catchment area for people to supply the temples. Non-domesticates such as ibises and

crocodiles were probably kept in environments such as pools or lakes where they were

fed regularly and maintained by temple personnel, and thus were managed, and

(p. 462)

to some extent, one might say that they were ‘farmed’ (Strabo, Falconer trans., 1912;

Preisigke and Spiegelberg, 1914; Ray, 1976; Herodotus, Gould trans., 1989; Bresciani,

2015). It is also possible that ibises were acquired by enterprising folk who lived near ibis

breeding areas and thus could capture birds or raid nests and supply the temples with

even more sacrificial victims. Thus, it is clear that the sourcing and maintenance, to

whatever degree, of the animals was a major component of economic activity in animal

cults. Further work on animal catacombs will elucidate exactly how significant a role they

played in both the cult and the economy.

Discussion

There is no doubt that animals played a major role in Egyptian religious and economic

life, particularly as sacrificial victims. While one is accustomed to the idea of a single or

even several animals being killed as food offerings to a deity (Posener-Kriéger, 1976;

Posener-Kriéger et al., 2006), it is the vast scale of animal mummies that gives one pause.

Unlike the meat from offerings, which was redistributed, animal mummies played no

further role in the economy or the physical life of either the priests or the populace.

Indeed, it is curious that creatures that were linked so closely with the gods were

Page 9 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

paradoxically bred (or imported) specifically to be killed, often brutally by strangulation,

having their skulls bashed in, or their nostrils slit. Paradoxically, the continuations of

these cults also guaranteed the local survival for many species, such as the Sacred Ibis,

which is now extinct in Egypt.

One can take the cynical view that for the priests at least, the production of animal

mummies as ex-votos was a way of wielding economic and social power: it provided

employment for themselves and the villagers around them in terms of breeding, caring

for, and feeding the animals and preparing the mummies; the sale of the mummies was a

way of enriching temple coffers, as well as tying their donors and producers to the

temples, the gods, and the state (Ikram, 2015c). However, the vast number of these votive

mummies indicates a heartfelt belief in their efficacy on the part of their givers, and

provided the donors with a mode of self-expression, identification, and interaction with

the divine that was uniquely Egyptian. For the donors, probably, the animals not only

conveyed prayers to the gods, but were themselves given a chance at an immortal

existence in close proximity to their gods, and thus were achieving a state of grace and

immortality that the donors themselves sought, and could only properly achieve with

their own death.

References

Armitage, P. L. and Clutton-Brock, J. (1980) ‘Egyptian mummified cats held by the British

Museum’, MASCA, Research Papers in Science and Archaeology, 1, 185–8.

Armitage, P. L. and Clutton-Brock, J. (1981) ‘A radiological and histological

(p. 463)

investigation into the mummification of cats from ancient Egypt’, Journal of

Archaeological Science, 8, 185–96.

Bagnani, G. (1952) ‘The great Egyptian crocodile mystery’, Archaeology, 5(2), 76–8.

Barta, W. (1963) Die Altägyptische Opferliste von der Frühzeit bis zur Griechisch-

Römischen Epoche, Berlin: Hessling.

Bresciani, E. (2015) ‘Sobek, Lord of the Land of the Lake’, in Ikram, S. (ed.) Divine

Creatures: Animal Mummies from Ancient Egypt, pp. 199–206. Cairo: American

University in Cairo Press.

Chaix, L. and Grant, A. (1992) ‘Cattle in ancient Nubia’, in Grant, A. (ed.) Les animaux et

leurs produits dans le commerce et les échanges/Animals and Their Products in Trade

and Exchange: actes du 3éme colloque internationale de l’homme et l’animal, Société de

Recherche Interdisciplinaire (Oxford 8–11 Novembre 1990). Anthropozoologica 16, pp.

61–6. Clichy: L’Homme et L’Animal, Société de Recherche Interdisciplinaire.

Charron, A. (1990) ‘Massacres d’animaux à la Basse Epoque’, Revue d’Égyptologie, 41,

209–13.

Page 10 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Daressy, G. and Gaillard, C. (1905) La faune momifiée de l’antique Égypte, Cairo: Institut

Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Davis, S. J. M. (2008) ‘‘Thou shalt take of the ram … the right thigh; for it is a ram of

consecration …’: some zoo-archaeological examples of body-part preferences’, in

D’Andria, F., De Grossi Mazzorin, J., and Fiorentino, G. (eds) Uomini, piante e animali

nella dimensione del sacro, pp. 63–70. Lecce: Università degli Studi di Lecce/Consiglio

Nazionale delle Ricerche.

Dodson, A. M. (2015) ‘Bull cults’, in Ikram, S. (ed.) Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies

from Ancient Egypt, pp. 72–105. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Driesch, von den, A. (1993) ‘The keeping and worshipping of baboons during the Later

Phase in Ancient Egypt’, Sartoniana, 6, 15–36.

Driesch, von den, A. and Boessneck, J. (1985) ‘Krankhaft veränderte Skelettreste von

Pavianen aus altägyptischer Zeit’, Tierärztliche Praxis, 13, 367–72.

Driesch, von den, A., Kessler, D., Steinmann, F., Berteaux, V., and Peters, J. (2005)

‘Mummified, deified and buried at Hermopolis Magna—the sacred birds from Tuna El-

Gebel, Middle Egypt’, Ägypten und Levante, 15, 203–44.

Dunand, F., Lichtenberg, R. and Charron, A. (2005) Des animaux et des hommes: une

symbiose égyptienne, Paris: Rocher.

Dunand, F., Lichtenberg, R., and Callou, C. (2015) ‘Dogs at el-Deir’, in Ikram, S., Kaiser, J.,

and Walker, R. (eds) Egyptian Bioarchaeology: Humans, Animals, and the Environment,

pp. 169–76. Amsterdam: Sidestone.

Emery, W. B. (1949) Great Tombs of the First Dynasty I, Cairo: Service des Antiquités.

Emery, W. B. (1954) Great Tombs of the First Dynasty II, London: Egypt Exploration

Society.

Emery, W. B. (1958) Great Tombs of the First Dynasty III, London: Egypt Exploration

Society.

Emery, W. B. (1974) Archaic Egypt, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Ghoneim, W. (1977) Die ökonomische Bedeutung des Rindes im alten Ägypten, Bonn:

Habelt.

Goudsmit, J. and Brandon-Jones, D. (2000) ‘Evidence from the Baboon Catacomb in North

Saqqara for a west Mediterranean monkey trade route to Ptolemaic Alexandria’, Journal

of Egyptian Archaeology, 86, 111–19.

Grant, A. (1991) ‘Economic or symbolic? Animals and ritual behaviour’, in Garwood P.,

Jennings, D., and Toms, J. (eds) Sacred and Profane: Archaeology, Ritual and Religion, pp.

109–14. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.

Page 11 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Hartley, M., Buck, A., and Binder, S. (2011) ‘Canine interments in the Teti Cemetery

North at Saqqara during the Graeco-Roman period’, in Coppens, F. and Krejsi, J. (eds)

Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010, pp. 17–29. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology.

(p. 464) Herodotus, trans. by Gould, J. (1989) The Histories II, III, New York: St. Martin’s

Press.

Ikram, S. (1995) Choice Cuts: Meat Production in Ancient Egypt, Leuven: Peeters.

Ikram, S. (2009) ‘Funerary food offerings’, in Barta, M. (ed.) Abusir XIII, Abusir South 2.

Tomb Complex of the Vizier Qar, His Sons Qar Junior and Senedjemib, and Iykai, pp. 294–

8. Prague: Dryada/Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University.

Ikram, S. (2011) ‘Food and funerals: sustaining the dead for eternity’, Polish Archaeology

in the Mediterranean, 20, 361–71.

Ikram, S. (2012) ‘From food to furniture: animals in ancient Nubia’, in Fisher, M.,

Lacovara, P., Ikram, S., and D’Auria, S. (eds) Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the

Nile, pp. 210–28. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Ikram, S. (ed.) (2015a) Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt, Cairo:

American University in Cairo.

Ikram, S. (2015b) ‘Experimental Archaeology: From Meadow to Em-baa-lming Table’, in

Graves-Brown, C. (ed.) Egyptology in the Present: Experiential and Experimental Methods

in Archaeology, pp. 53–74. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales.

Ikram, S. (2015c) ‘Speculations on the Role of Animal Cults in the Economy of Ancient

Egypt’, in Massiera, M., Mathieu, B., and Rouffet, Fr. (eds) Apprivoiser le sauvage/Taming

the Wild (CENiM 11), pp. 211–28. Montpellier: University Paul Valéry Montpellier 3.

Ikram, S., Bosch, C., and Spitzer, M. (in prep.) ‘Offerings to Thoth and Horus: the avian

deposit of Theban Tomb 12, the Chapel of Hery’, Journal of the American Research Center

in Egypt.

Ikram, S. and Iskander, N. (2002) Catalogue Général of the Egyptian Museum: Non-

Human Mummies, Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquities Press.

Ikram, S., Nicholson, P. T., Bertini, L., and Hurley, D. (2013) ‘Killing man’s best friend?’,

Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 28(2), 48–66.

Ikram, S., R. Slabbert, I. Cornelius, A. du Plessis, L. C. Swanepoel, and H. Weber. (2015)

‘Fatal force-feeding or Gluttonous Gagging? The death of Kestrel SACHM 2575’, Journal

of Archaeological Science, 63, 72–7.

Juvenal, trans. by Rudd, N. (1991) The Satires—Juvenal, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kessler, D. (1986) ‘Tierkult’, in Helck, W. and Westendorf, W. (eds) Lexikon der

Ägyptologie VI, pp. 571–87. Weisbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Page 12 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Kessler, D. and Nur el-Din, A. (2015) ‘Tuna El-Gebel: millions of ibises and other animals’,

in Ikram, S. (ed.) Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies from Ancient Egypt, pp. 120–63.

Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Lehner, M. (2000) ‘The fractal house of pharaoh: ancient Egypt as a complex adaptive

system, a trial formulation’, in Kohler, T. A. and Gumerman, G. G. (eds) Dynamics in

Human and Primate Societies, pp. 275–353. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Loat, W. L. S. (1914) ‘The ibis cemetery at Abydos’, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 1,

40.

Lortet, L. C. and Gaillard, C. (1903–1909) La faune momifiée de l’ancienne Egypte, Lyon:

Archives du Muséum Histoire Naturelle de Lyon VIII.

Murnane, W. J. (1980) United with Eternity: A Concise Guide to the Monuments of

Medinet Habu, Chicago/Cairo: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago/American

University in Cairo Press.

Nerlich, A. G., Parsche, F., Driesch, von den, A., and Löhrs, U. (1993) ‘Osteopathological

findings in mummified baboons from Ancient Egypt’, International Journal of

Osteoarchaeology, 3, 189–98.

Posener-Kriéger, P. (1976) Les archives du temple funéraire de Neferirkare-Kakai, 1–2,

Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

(p. 465) Posener-Kriéger, P., Verner, M., and Vymazalova, H. (2006) Abusir X: The Pyramid

Complex of Raneferef, the Papyrus Archive, Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology.

Preisigke, F. and Spiegelberg, W. (1914) Die Prinz-Joachim Ostraka, Strasbourg: K. J.

Trübner.

Ray, J. D. (1976) The Archive of Hor, London: Egypt Exploration Society.

Ray, J. D. (2001) ‘Animal cults’, in Redford, D. B. (ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient

Egypt, pp. 345–8. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ray, J. D. (2011) Texts from the Baboon and Falcon Galleries: Demotic, Hieroglyphic and

Greek Inscriptions from the Sacred Animal Necropolis, North Saqqara, London: Egypt

Exploration Society.

Ray, J. D. (2013) Demotic Ostraca and Other Inscriptions from the Sacred Animal

Necropolis, North Saqqara, London: Egypt Exploration Society.

Rossel, S. (2007) ‘The Development of Productive Subsistence Economies in the Nile

Valley: Zooarchaeological Analysis at El-Mahasna and South Abydos, Upper Egypt’.

Unpublished PhD dissertation, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA).

Page 13 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

Animals in ancient Egyptian religion: belief, identity, power, and economy

Smelik, K. A. D. and Hemelrijk, E. A. (1984) ‘‘Who knows not what monsters demented

Egypt worships?’ Opinions on Egyptian animal worship in antiquity as part of the ancient

conception of Egypt’, in Haase, W. (ed.) Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt

17(4), pp. 1853–2000. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Smith, H. S., Andrews, C. A. R., and Davies, S. (2011) The Sacred Animal Necropolis at

North Saqqara: The Mother of Apis Inscriptions 1–2, London: Egypt Exploration Society.

Strabo, trans. by Falconer, W. (1912) The Geography of Egypt, Vol. 17, London: G. Bell

and Sons.

Walz, T. (1978) Trade Between Egypt and Bilad-as-Sudan, 1700–1820, Cairo: Institut

Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

Warburton, D. (2000) ‘State and economy in ancient Egypt’, in Denemark, R., Friedman,

J., Gills, B. K., and Modelski, G. (eds) World System History: The Social Science of Long

Term Change, pp. 169–84. London: Routledge.

Weinstein, J. M. (1973) ‘Foundation Deposits in Ancient Egypt’. Unpublished PhD

dissertation, University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia).

Wilkinson, R. (2003) The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, London/Cairo:

Thames and Hudson/American University in Cairo Press.

Zivie, A. and Lichtenberg, R. (2015) ‘The cats of the goddess Bastet’, in Ikram, S. (ed.)

Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt, pp. 106–19. Cairo: American

University in Cairo Press.

Salima Ikram

Salima Ikram is Distinguished University Professor of Egyptology at the American

University in Cairo and has worked throughout Egypt on faunal assemblages as well

as animal mummies, in addition to working as a mortuary archaeologist. Her

research interests focus on the changing role that animals played in the diet and

economy of ancient Egypt. She has published extensively on these and other topics.

Page 14 of 14

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Universidad de Chile; date: 09 April 2019

You might also like

- Mackenzie Egyptian Myth and LegendDocument162 pagesMackenzie Egyptian Myth and LegendPoliane da PaixãoNo ratings yet

- Uljas Sami The Modal System of Earlier Egyptian Complement CDocument445 pagesUljas Sami The Modal System of Earlier Egyptian Complement COsnat YoussinNo ratings yet

- The Ancient Egyptian City of Thebes: Prepared By: Professor Dr. Abeer AminDocument14 pagesThe Ancient Egyptian City of Thebes: Prepared By: Professor Dr. Abeer AminHanin AlaaNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Mathematics: Hieroglyphs and Ancient NumeralsDocument2 pagesEgyptian Mathematics: Hieroglyphs and Ancient NumeralsJaymarkCasasNo ratings yet

- Papiro Hawara PDFDocument192 pagesPapiro Hawara PDFJoshua PorterNo ratings yet

- Art of Ancient EgyptDocument16 pagesArt of Ancient EgyptDesiree MercadoNo ratings yet

- 3 CairoDocument1,242 pages3 CairoShihab Eldein0% (1)

- Pope, 25th DynastyDocument22 pagesPope, 25th DynastyAnonymous 5ghkjNxNo ratings yet

- Arkell 1955 Hator PDFDocument3 pagesArkell 1955 Hator PDFFrancesca IannarilliNo ratings yet

- ANCIENT EGYPT: KEYS TO HIEROGLYPHSDocument6 pagesANCIENT EGYPT: KEYS TO HIEROGLYPHSgabisaenaNo ratings yet

- Brand, JAC 31 (2016), Reconstructing The Royal Family of Ramesses II and Its Hierarchical Structure PDFDocument45 pagesBrand, JAC 31 (2016), Reconstructing The Royal Family of Ramesses II and Its Hierarchical Structure PDFAnonymous 5ghkjNxNo ratings yet

- Cave of Beasts Ancient Egyptian Rock ArtDocument7 pagesCave of Beasts Ancient Egyptian Rock ArtEllieNo ratings yet

- Throne of TutankhamunDocument10 pagesThrone of Tutankhamunapi-642845130No ratings yet

- Shasu Nomads of Ancient LevantDocument22 pagesShasu Nomads of Ancient LevantLaécioNo ratings yet

- An Archaic Representation of HathorDocument3 pagesAn Archaic Representation of HathorFrancesca Iannarilli100% (1)

- LexicografiaDocument331 pagesLexicografiamenjeperreNo ratings yet

- Predynastic Period: Badarian CultureDocument2 pagesPredynastic Period: Badarian CulturejamessonianNo ratings yet

- The Wine Jars Speak A Text StudyDocument191 pagesThe Wine Jars Speak A Text StudyPaula VeigaNo ratings yet

- Archaeological S 04 e GypDocument138 pagesArchaeological S 04 e GypEgiptologia BrasileiraNo ratings yet

- Naqada CultureDocument3 pagesNaqada CultureNabil RoufailNo ratings yet

- Kherty (Neter)Document2 pagesKherty (Neter)Alison_VicarNo ratings yet

- Archaic EgyptDocument24 pagesArchaic Egyptapi-428137545No ratings yet

- Excavating The Afterlife The ArchaeologyDocument6 pagesExcavating The Afterlife The ArchaeologyClaudiaPirvanNo ratings yet

- GenealogicalDocument34 pagesGenealogicalMohamed SabraNo ratings yet

- A Handbook of Egyptian Religion - A ErmanDocument281 pagesA Handbook of Egyptian Religion - A ErmanDan LangloisNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian Art Forms and Their Significance in Preserving CultureDocument4 pagesAncient Egyptian Art Forms and Their Significance in Preserving CultureManishaNo ratings yet

- The Dream Stela of Thutmosis IvDocument6 pagesThe Dream Stela of Thutmosis IvNabil RoufailNo ratings yet

- 604270Document9 pages604270Mohamed NassarNo ratings yet

- Verner - Taweret Statue - ZAS 96 (1970)Document13 pagesVerner - Taweret Statue - ZAS 96 (1970)Imhotep72100% (1)

- Ancient Egypt Art Architecture 3-4Document2 pagesAncient Egypt Art Architecture 3-4ermald1100% (1)

- Geisen - The Ramesseum DramaticDocument327 pagesGeisen - The Ramesseum DramaticPaula VeigaNo ratings yet

- AJA No.3Document902 pagesAJA No.3zlatkoNo ratings yet

- Abusir Archive Administraion هاااامArchives in Ancient Egypt 2500-1000 BCEDocument101 pagesAbusir Archive Administraion هاااامArchives in Ancient Egypt 2500-1000 BCEShaimaa AbouzeidNo ratings yet

- F. Ll. Griffith, The Inscriptions of Siut and Der RifehDocument64 pagesF. Ll. Griffith, The Inscriptions of Siut and Der RifehKing_of_WeddingNo ratings yet

- Museum Bulletin Details Amulets from Giza CemeteryDocument8 pagesMuseum Bulletin Details Amulets from Giza CemeteryomarNo ratings yet

- Lorton - The Theology of Cult Statues in Ancient EgyptDocument88 pagesLorton - The Theology of Cult Statues in Ancient EgyptAnthony SooHooNo ratings yet

- War in Old Kingdom Egypt-LibreDocument43 pagesWar in Old Kingdom Egypt-LibreAlairFigueiredoNo ratings yet

- Foriegn PharaohsDocument43 pagesForiegn PharaohsnilecruisedNo ratings yet

- Coffin Texts shed light on granariesDocument53 pagesCoffin Texts shed light on granariesObadele KambonNo ratings yet

- Spell to Prevent Being Ferried to the EastDocument25 pagesSpell to Prevent Being Ferried to the EastAnonymous lKMmPk0% (1)

- 01 AllenDocument26 pages01 AllenClaudia MaioruNo ratings yet

- MESKELL, An Archaeology of Social RelationsDocument35 pagesMESKELL, An Archaeology of Social RelationsRocío Fernández100% (1)

- Egypt and Nubia Prehistory ReviewedDocument4 pagesEgypt and Nubia Prehistory Reviewedsychev_dmitry100% (1)

- The Silver Pharaoh MysteryDocument4 pagesThe Silver Pharaoh MysteryHaydee RocaNo ratings yet

- Palermo StoneDocument8 pagesPalermo StoneArie Reches PCNo ratings yet

- Reisner Indep 4 11 1925Document6 pagesReisner Indep 4 11 1925Osiadan Khnum PtahNo ratings yet

- Ethics and The Archaeology of ViolenceDocument3 pagesEthics and The Archaeology of ViolencePaulo ZanettiniNo ratings yet

- Aram17 2005 Patrich Dionysos-DusharaDocument20 pagesAram17 2005 Patrich Dionysos-Dusharahorizein1No ratings yet

- A Concise Dictionary of Egyptian Archaeology 1000036059 PDFDocument245 pagesA Concise Dictionary of Egyptian Archaeology 1000036059 PDFsoy yo o noNo ratings yet

- 3bulletin de L Institut D EgypteDocument54 pages3bulletin de L Institut D Egyptefadyrodanlo0% (1)

- End of Early Bronze AgeDocument29 pagesEnd of Early Bronze AgeitsnotconfidentialsNo ratings yet

- Biggs Medicine, SurgeryDocument19 pagesBiggs Medicine, Surgerymary20149No ratings yet

- Prophecy of NefertyDocument21 pagesProphecy of NefertyDr. Ọbádélé KambonNo ratings yet

- Who Are The Deities Concealed Behind The Rabbinic ExpressionDocument13 pagesWho Are The Deities Concealed Behind The Rabbinic ExpressionJohn KellyNo ratings yet

- Scorpions in Ancient Egypt - El-Hennawy 2011Document14 pagesScorpions in Ancient Egypt - El-Hennawy 2011elhennawyNo ratings yet

- The Ancient Egyptian Doctrine of the Immortality of the SoulFrom EverandThe Ancient Egyptian Doctrine of the Immortality of the SoulNo ratings yet

- Journal of Archaeological ScienceDocument10 pagesJournal of Archaeological ScienceCatalinaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Archaeological ScienceDocument7 pagesJournal of Archaeological ScienceCatalinaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Archaeological ScienceDocument10 pagesJournal of Archaeological ScienceCatalinaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Archaeological ScienceDocument7 pagesJournal of Archaeological ScienceCatalinaNo ratings yet

- BK88PUB4 Table of ContentDocument17 pagesBK88PUB4 Table of ContentwalNo ratings yet

- Aws Cwi BrochureDocument16 pagesAws Cwi BrochureMS SIVAKUMARNo ratings yet

- Class Notations Table - Jan14Document269 pagesClass Notations Table - Jan14shepeNo ratings yet

- New Worlds Emerging: European Colonization of the Americas and OceaniaDocument8 pagesNew Worlds Emerging: European Colonization of the Americas and OceaniaSkyler KesslerNo ratings yet

- 2018 Basic Rate Making SampleDocument333 pages2018 Basic Rate Making SampleBNo ratings yet

- French PolynesiaDocument5 pagesFrench PolynesiaMuhammad Jafor IqbalNo ratings yet

- SeptemberDocument5 pagesSeptemberElks371No ratings yet

- Name Sr. No. Exam Seat NoDocument9 pagesName Sr. No. Exam Seat NoSakshi HulgundeNo ratings yet

- Marx's Dialectic of LabourDocument28 pagesMarx's Dialectic of LabourbarbarelashNo ratings yet

- US Islamic World Forum Doha, Qatar February 2010Document58 pagesUS Islamic World Forum Doha, Qatar February 2010Kim HedumNo ratings yet

- Global Production NetworksDocument25 pagesGlobal Production NetworksMatthew AndrewsNo ratings yet

- The Incan DeclineDocument3 pagesThe Incan DeclineAndre GuignardNo ratings yet

- The Hogbetsotso FestivalDocument3 pagesThe Hogbetsotso FestivalTheophilus BaidooNo ratings yet

- Study on Feasts and Festivals of the Maring TribesDocument5 pagesStudy on Feasts and Festivals of the Maring TribesThangminlun HaokipNo ratings yet

- Marine Piping System PDFDocument233 pagesMarine Piping System PDFNaresh100% (4)

- All Saints Costume IdeasDocument4 pagesAll Saints Costume Ideasceci75No ratings yet

- 57 Iwori OturuponDocument20 pages57 Iwori OturuponIfadara Elebuibon100% (2)

- ASME B31.9 - 2014 Building Services Piping Pages 1 - 50 - Text Version - AnyFlipDocument89 pagesASME B31.9 - 2014 Building Services Piping Pages 1 - 50 - Text Version - AnyFlipEstuardo Olan100% (4)

- The CaseDocument12 pagesThe CaseAshok Avs100% (1)

- Cadet HandbookDocument58 pagesCadet HandbookBlairnutritionNo ratings yet

- WWF METT Handbook 2016 FINAL PDFDocument75 pagesWWF METT Handbook 2016 FINAL PDFMagdalena TabaniagNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Community Development District Performance in Makassar CityDocument12 pagesEvaluating Community Development District Performance in Makassar CityAkhmad Edwin Indra PratamaNo ratings yet

- Drying sodium carbonate at 270°C for 1 hourDocument4 pagesDrying sodium carbonate at 270°C for 1 hourShaina Anne BuenavidesNo ratings yet

- History of The Statistical Classification of Diseases and Causes of DeathDocument71 pagesHistory of The Statistical Classification of Diseases and Causes of DeathvthiseasNo ratings yet

- Zimbabwe University 2018 Exams Question on Ubuntu Philosophy and Corporate GovernanceDocument7 pagesZimbabwe University 2018 Exams Question on Ubuntu Philosophy and Corporate GovernancejrmutengeraNo ratings yet

- Philippine History - La Liga FilipinaDocument1 pagePhilippine History - La Liga FilipinaDummy OneNo ratings yet

- UN-Habitat - 2015 - Training Module Slum UpgradingDocument54 pagesUN-Habitat - 2015 - Training Module Slum UpgradingUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)100% (2)

- ICMSETDocument9 pagesICMSETPramudyo BayuNo ratings yet

- Ads 452 Chapter 6Document36 pagesAds 452 Chapter 6NadhirahNo ratings yet

- Pollinia - The Irish Orchid Society NewsletterDocument32 pagesPollinia - The Irish Orchid Society NewsletterLaurence MayNo ratings yet