Professional Documents

Culture Documents

4 Common Misconceptions About ACT - Russ Harris PDF

4 Common Misconceptions About ACT - Russ Harris PDF

Uploaded by

Thalita Vargas0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views14 pagesOriginal Title

4 Common Misconceptions About ACT - Russ Harris.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views14 pages4 Common Misconceptions About ACT - Russ Harris PDF

4 Common Misconceptions About ACT - Russ Harris PDF

Uploaded by

Thalita VargasCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

4 Common Misconceptions About ACT

There are unfortunately a lot of common misperceptions about ACT. Here are four of the most

common ones I encounter.

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 1

#1: ACT Doesn’t Change Your Thinking

One of the biggest misconceptions about ACT is that it “doesn’t change your thinking.” I hope

and trust you can see that isn’t the case. When clients (and therapists) encounter ACT, it

usually dramatically changes the way they think about a vast range of topics and issues,

including the nature and purpose of their own thoughts and emotions, the way they want to

behave, the way they want to treat themselves and others, what they want their lives to be

about, effective ways to live and act and deal with their problems, what motivates them, why

they do the things they do, and so on.

However, ACT doesn’t achieve this by challenging, disputing, disproving, or invalidating

thoughts; nor does it help people to avoid, suppress, distract from, dismiss, or “rewrite” their

thoughts or try to convert their “negative” thoughts into “positive” ones.

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 2

ACT helps people to change their thinking through:

(a) defusing from unhelpful cognitions and cognitive processes;

(b) developing new, more flexible and effective ways of thinking, in addition to their other

cognitive patterns.

Why did I italicize the words in addition? Because we don’t get to eliminate unhelpful

cognitive repertoires. As the ACT saying goes, “There’s no delete button in the brain.”

We can develop new ways of thinking, but that doesn’t eliminate the old ones.

As I say to clients, “If you learn to speak Hungarian, that won’t eliminate English from your

vocabulary.”

So again and again, we emphasize this important point to our clients in many different ways.

For example: “Logically and rationally you know these thoughts aren’t true—and that won’t

stop them from reappearing. Or: “Yes, you can see clearly that this pattern of thinking isn’t

helpful—and that won’t stop your mind from doing it.” Or: “So you know when this story

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 3

hooks you, it pulls you into away moves—and knowing that won’t get rid of the story; it will

keep coming back.”

Here are just some of the many ways ACT actively fosters flexible thinking:

• Reframing

• Flexible perspective taking

• Compassion and self-compassion

• Flexible goal setting, problem solving, action planning, and strategizing

• Considering your beliefs, ideas, attitudes and assumptions in terms of workability

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 4

#2: ACT Isn’t Interested In Symptom Reduction

The story goes that that the “ACT therapists are not interested in symptom reduction; they are

only interested in values-based living.” I can see where this story comes from, but it’s a

caricature. I think it's much fairer to say it something like this: "The common ACT stance is that

the therapist aims to increase the client's quality of life and reduce their suffering through

helping them to live by their values and utilise new skills to reduce the impact and influence of

their painful thoughts and feelings."

I personally encourage ACT therapists and coaches as part of informed consent to tell clients

"We'll be learning new skills to handle painful thoughts and feelings more effectively; to

reduce their impact and influence over you, so they don't hold you back, run your life, jerk you

around." Most clients respond very well to this.

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 5

For sure, the primary aim of ACT is values-based living, not symptom-reduction; however

significant symptom reduction almost always happens as a by-product of ACT – and often,

rapidly. And for sure we are interested in that symptom reduction; this is why it gets

measured in almost all of the 1000+ published studies on ACT. And what almost all of those

studies show is that ACT gives effective and sustainable symptom reduction as a by-product of

mindful, values-based living. Indeed, in many control trials, ACT gives better symptom

reduction than other models where this is the primary aim.

So it’s very important how we present all this to clients. Present it somewhat as I've suggested

above, and it very much meets their expectations and needs. Present it as "We aren't

interested in symptom reduction here!" and you'll have many problems.

Before signing off on this point, one more thing to consider …

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 6

What Do We Actually Mean By Symptom Reduction?

The common understanding of ‘symptom reduction’ is a decrease in the frequency and

intensity of unwanted thoughts, feelings, emotions, sensations, memories, etc. However,

there’s another way to think about this. Suppose we conceive common client symptoms as

excessive or problematic degrees of:

• Distractibility, disengagement, dissociation

• Operating on autopilot, mindlessness

• Allowing cognitions to dominate actions or awareness in problematic ways

• Lack of meaning and purpose and fulfilment in life

• Ineffective or self-defeating patterns of action that tend to make life worse

• Amplifying the frequency and impact of painful emotions through struggling with them

If we think of these as ‘symptoms’, then for sure, ACT actively tries to reduce them!

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 7

#3: Experiential Avoidance (EA) is the Overarching Problem in ACT

EA is a common problem which we often target in ACT. But it isn’t always a problem, and it is

rarely if ever the only one. First, let’s be clear that EA is not the opposite of values-based

living. EA is often harmless, and sometimes extremely helpful. I do a lot of stuff that's

experiential avoidance but doesn't pull me away from my values.

A few examples:

I take aspirin when I have a headache, to make the pain go away.

At certain times, in certain contexts, I find it very useful and life-enhancing to distract myself.

Sometimes, in specific contexts, I will use relaxation techniques to actively reduce my stress

and anxiety.

Those are all examples of EA, but they are values-congruent behaviours that work well for me

and enhance my life and wellbeing in those specific contexts.

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 8

What Motivates Values-Incongruent Ineffective Behaviour?

Values-incongruent ineffective behaviours are often motivated by EA. However, they are also often

motivated by other factors. For example, they are often under appetitive control motivated by cognitive

fusion: fusion with rigid rules, fusion with desires, fusion with wanting to be right, and so on. Here are

some of the most common reinforcing consequences for values-incongruent ineffective behaviour:

• Escape/avoid people, places, situations, events, etc. (overt avoidance)

• Escape/avoid unwanted thoughts & feelings (experiential avoidance)

• Feel good

• Get your needs met

• Gain attention

• Look good (to yourself or others)

• Feel like you are right and others are wrong

• Make sense (of life, the world, yourself, others etc.)

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 9

The Overarching Problem in ACT is Cognitive Fusion

The overarching problem in ACT is cognitive fusion - not experiential avoidance. Experiential avoidance is

normal, and only becomes problematic when excessive, rigid, inappropriate.

And what underpins excessive, rigid inappropriate EA is cognitive fusion: most commonly, a) fusion with

judgments that these feelings/thoughts/emotions/sensations/memories are “bad”, and b) fusion with

the rule “I need to get rid of them.” So problematic levels of EA are one of the many problems that

cognitive fusion can give rise to.

(Footnote: keep this in mind when comparing the choice point, the bull’s eye, and the matrix. In the

matrix, the term “away moves” usually means “experiential avoidance” or “moving away from pain”; it

refers to behaviours under aversive control, motivated by experiential avoidance, which may or may not

be values-incongruent. In the bull’s eye and the choice point, the term “away moves” means “moving

away from values”; it refers to values-incongruent ineffective behaviours under appetitive or aversive

control, motivated by cognitive fusion or EA or any of the other reinforcers mentioned above)

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 10

#4: ACT Is Too Directive, Not Person-Centred

Person-centred (or client-centred) therapy or counselling is largely based on/shaped by the

work of the enormously influential psychotherapist, Carl Rogers. ACT has much in common

with person-centred therapy. For example, in ACT:

• client and therapist are equals

• therapist has a Rogerian stance of unconditional positive regard for the client (ACT even

borrows Rogers’ famous metaphor about “looking at our clients as sunsets”)

• therapist focuses on the client's subjective view of the world

• client is responsible for improving his own life (as opposed to being diagnosed and

treated by the therapist)

• therapist works with what the client brings to session and wants to focus on,

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 11

• therapist raises client's awareness & helps them live by their own values (similar to

Rogers’ concept of ‘congruence’)

• therapist helps client to function like the person they want to be (similar to Rogers

concept of 'self-actualization')

• therapist is genuine and willing to self-disclose

• therapist focuses mostly on the present and the future, rather than the past

For sure there are many differences between ACT and person-centred or client-centred

therapy; at the same time, there are many commonalities. (No surprise that ACT has been

described as an existential, humanistic, person-centred, mindfulness-based, cognitive

behavioural therapy � �)

This discussion of course begs the question …

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 12

How Directive Are We In ACT?

To have a Rogerian or person-centred stance as a therapist does not mean you have to be

totally non-directive in your sessions. When doing ACT, we are Rogerian or person-centred in

all the ways outlined above; and we can also be as directive or nondirective as we wish.

How directive we are depends on a) the capabilities of the client and b) the demands of the

situation.

For low-functioning clients, with many problems and significant deficits in coping skills, we will

usually need to be fairly directive. For example, we’ll usually need to set a clear agenda at the

start of each session, and steer the client back to it as often as needed in order to ensure she

actively learns new skills, clarifies values, sets goals, and creates action plans during the

session.

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 13

But with higher-functioning, self-motivated clients, we can be much less directive. So we can

titrate how directive we are in any given session to suit the needs of the unique client in front

of us.

It’s impossible, however, to be completely nondirective when teaching people mindfulness

skills; we do need to give instructions, suggestions, and feedback to people to ensure they

learn and apply their new skills. However, this doesn’t mean we are telling people how to live

their lives; rather we are helping people build and apply the skills that will enable them to live

their lives the way they really want to.

© Russ Harris 2018 | www.ImLearningACT.com Page 14

You might also like

- Being Flexible With Dropping Anchor - Don't Stick To The Script - Russ HarrisDocument5 pagesBeing Flexible With Dropping Anchor - Don't Stick To The Script - Russ HarrisThalita VargasNo ratings yet

- ACT Case Formulation Worksheet - April 2019 Version - Russ HarrisDocument2 pagesACT Case Formulation Worksheet - April 2019 Version - Russ HarrisBeaNo ratings yet

- Being Flexible With Dropping Anchor - Don't Stick To The Script - Russ HarrisDocument5 pagesBeing Flexible With Dropping Anchor - Don't Stick To The Script - Russ HarrisThalita VargasNo ratings yet

- Act Exposures Worksheet Think CBT V 27.11.17Document1 pageAct Exposures Worksheet Think CBT V 27.11.17Thalita VargasNo ratings yet

- Rebuilding Trust - by Russ HarrisDocument2 pagesRebuilding Trust - by Russ HarrisThalita VargasNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (843)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5808)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Purpose Risk Identification Responsibilities Risk Assessment Risk Response Risk Mitigation Risk Contingency PlanningDocument4 pagesPurpose Risk Identification Responsibilities Risk Assessment Risk Response Risk Mitigation Risk Contingency PlanningQuality Unit 1 Ajay PandeyNo ratings yet

- Sepsis in A SnapDocument1 pageSepsis in A SnapjufnasNo ratings yet

- The 7 Biggest Mistakes Made by Singers..Document17 pagesThe 7 Biggest Mistakes Made by Singers..César De La Cruz OlivaNo ratings yet

- Terlaris Shopee Oktober 2022Document1,025 pagesTerlaris Shopee Oktober 2022Gflexku TeNo ratings yet

- Try Scribd FREE For 30 Days To Access Over 125 Million Titles Without Ads or Interruptions!Document1 pageTry Scribd FREE For 30 Days To Access Over 125 Million Titles Without Ads or Interruptions!eyaNo ratings yet

- Monolithic Solutions CHAIRSIDE: Instructions For UseDocument52 pagesMonolithic Solutions CHAIRSIDE: Instructions For UsemohammadNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Attitude of Dental Hygiene Practice Among Primary 4 - 6 Pupils of Archbishop Peter Akinola International School in Afikpo, Ebonyi StateDocument50 pagesKnowledge and Attitude of Dental Hygiene Practice Among Primary 4 - 6 Pupils of Archbishop Peter Akinola International School in Afikpo, Ebonyi StateSamuel NwachukwuNo ratings yet

- Significance of The StudyDocument2 pagesSignificance of The StudyMiguel VienesNo ratings yet

- Roehampton Hospital Case Study - Part 2Document2 pagesRoehampton Hospital Case Study - Part 2akhil paulNo ratings yet

- A Immediate Implant With Provisionaliztion Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyDocument12 pagesA Immediate Implant With Provisionaliztion Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyAhmed BadrNo ratings yet

- 5.0 Indoor Air PollutionDocument107 pages5.0 Indoor Air Pollutionsarah575No ratings yet

- TokoJAV.comDocument166 pagesTokoJAV.comKsatrio Pinayung Rizqi50% (2)

- 107 RLE Group 5 1F Newborn Delivery Final OutputDocument79 pages107 RLE Group 5 1F Newborn Delivery Final OutputJr CaniaNo ratings yet

- New Ao Trauma PR Acetab Pelvic Szeged 08.22Document16 pagesNew Ao Trauma PR Acetab Pelvic Szeged 08.22Dr.upendra goudNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration (Rembulat v. Rembulat)Document9 pagesMotion For Reconsideration (Rembulat v. Rembulat)cagayatNo ratings yet

- 904 New Jeevan Arogya PresentationDocument2 pages904 New Jeevan Arogya PresentationDhiman NaskarNo ratings yet

- 3 Simple Steps EbookDocument33 pages3 Simple Steps EbookDušan PaničNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mapeh 6 - Q4 - W2Document4 pagesDLL - Mapeh 6 - Q4 - W2Aldrin Moreno EpagoNo ratings yet

- Hope 1Document3 pagesHope 1Novy MoranNo ratings yet

- Biginner's Guide To Feldenkrais PDFDocument4 pagesBiginner's Guide To Feldenkrais PDFAna Carolina PetrusNo ratings yet

- 115 Part BDocument5 pages115 Part Bapi-662326591No ratings yet

- GHS Format-sds-Gp CleanDocument8 pagesGHS Format-sds-Gp CleanAlan TanNo ratings yet

- Can Marijuana Help With or Prevent Alzheimer'sDocument10 pagesCan Marijuana Help With or Prevent Alzheimer'sLorina BoligNo ratings yet

- Pmls Transes Prelims 1Document5 pagesPmls Transes Prelims 1Kimberly Jean OkitNo ratings yet

- PeplauDocument13 pagesPeplauAnusha Verghese100% (1)

- Legal Aspects of General Dental Practice: Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument6 pagesLegal Aspects of General Dental Practice: Multiple Choice QuestionsDinda OkkyanaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Practice in Arab CountriesDocument5 pagesMental Health Practice in Arab CountriesRebecca AntoniosNo ratings yet

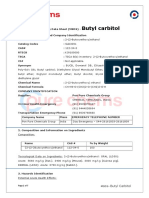

- MSDS Butyl CarbitolDocument7 pagesMSDS Butyl CarbitolrezaNo ratings yet

- Workplace Resilience Scale Winwood2013 PDFDocument8 pagesWorkplace Resilience Scale Winwood2013 PDFAmy BCNo ratings yet

- PE POV On COVID-19 - v1.0 FINALDocument21 pagesPE POV On COVID-19 - v1.0 FINALTony GemayelNo ratings yet