Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IR Thermography For Wildlife Exposed To Oil-Reese-Deyoe

Uploaded by

alexanderOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IR Thermography For Wildlife Exposed To Oil-Reese-Deyoe

Uploaded by

alexanderCopyright:

Available Formats

Practical applications of Infrared Thermography in the rescue,

recovery, rehabilitation and release of wildlife following

external exposure to oil.

Judith Reese-Deyoe

Raven Infrared

ABSTRACT

As oil exploration, industry, and transportation reaches every corner of the globe, so too do the risks of the

inadvertent and hazardous exposure of wildlife to oil based pollutants. Once an accidental release has

occurred and wildlife has been exposed, persons or trained teams may respond to counter and correct the

often lethal affects of oiling. Practical applications of Infrared Thermography have yet to be fully applied to

such events and it is here proposed to be a potentially valuable tool at many of the sequential phases of

wildlife rescue: from recovery, rehabilitation and ultimately to release.

In early 2008 under the direction of US Fish and Wildlife Service, 31 oiled and injured Bald eagles were

transferred from Kodiak Island and admitted to the Bird Treatment and Learning Center, in Anchorage,

Alaska. This impromptu urban opportunity facilitated the first official local application of Infrared

Thermography for Eagle assessment and monitoring, but has since yielded encouraging quantitative data,

comparative digital documentation and baseline procedural recommendations for similar practical

applications.

In light of these developments - radiometric thermal imaging may also be well suited for remote wildlife rescue

scenarios by providing: day or night location of heat emitting survivors; immediate enhanced qualitative visual

assessments of rescued animals; aid in injury diagnosis; quantitative, non-invasive monitoring during

treatment; easily captured and stored digital documentation; and the establishment of species specific

thermal insulating criteria which may be used to validate rehabilitation and ultimate release of treated birds

and mammals.

Figure 1. An oiled Gannet just before being rescued at Prestige Oil spill. This bird and

thousands of others were affected by a tanker spill off the Spanish Coast in 2002 (IFAW Photo)

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

INTRODUCTION

This paper is an investigative report summarizing and suggesting practical applications of Infrared

Thermography in the rescue, recovery, rehabilitation and release of wildlife following external exposure to oil.

A recent application case history follows.

Did you know that a seemingly harmless glob of oil the size of a dime could kill a bird? Every year

millions of water birds die due to oil from a plethora of sources such a jet skis and outboard motors, to the

very oil washed off our streets after a rain. We remember all too well the devastating effects of those spills

that occur when tankers accidentally loose their cargo, but there are thousands of small spills occurring daily

and around the world that go unreported and unnoticed.

Wildlife inadvertently exposed to oil-based pollutants inevitably find the substance adhering to fur and

feathers; causing matting, separation, loss of thermal insulation, loss of buoyancy and sensitive skin

exposure. Ingestion of the substance frequently follows as the animal’s instinctual response to preen and

clean becomes incessant. This process then accumulates harmful toxins within the body which severely

compromise the internal organs and may lead to death. The rapid response and effective actions of wildlife

rescue teams in the field are critical elements in intercepting this deadly cycle and moving impacted animals

to higher probabilities of survival.

Figure 2. Left - An oiled sea lion awaits treatment Right – example of a Seal Thermogram, Courtesy of the

Alaska Sea Life Center

As in any disaster, an orderly progression of steps and processes can guide the responding groups to their

goals with maximum efficiency. In a wildlife response effort the steps involved are variably stated but

ultimately the same - they entail the initial response by the Oiled Wildlife Care Network (OWCN - activation);

the rescue and retrieval of the affected wildlife(OWCN Search and Collection); the assessment and treatment

(OWCN – Intake and Stabilization); the rehabilitation (OWCN – Cleaning) and the ultimate recovery and

release (OWCN – same). It is through these steps –each one uniquely diversified and incredibly valuable that

I believe Thermal Imaging can and will debut its own uniquely diverse potential. For to see the emitted heat

of a stranded animal as a marker of location; or an indication of injury; or a quantifier of health; a qualifier of

heat loss; or a form of documentation is the future of Infrared in our world. Transferred to us on a

wavelength, invisible but measurable, we have a new integral interpretive tool that represents the temporal

state of an energetic condition in time. Infrared Thermal Imaging can be and will be the next technological tool

to expedite and enhance the future efficiency of our responsible aid to oiled wildlife.

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

APPLICATION OF THERMAL IMAGING IN WILDLIFE RESCUE

Rescue and Retrieval:

After more than 30 years of military management and development, Infrared technology was released from its

secrecy and was given to the American people in the late 1970s. Despite its diversified capabilities –

equipment costs and fear laden follies had IRs mysterious potential shelved or discredited, until just recently.

As the public entered the electronic/information age, the place for Infrared in our

lives was honed by military marvels, marketing and movies of miraculous

technologies that will someday revolutionize our lives. For example, we are all

aware that most contemporary efforts in search and rescue are most effectively

done from the air. An aerial platform affords us a greater field of view, a more

perpendicular view minimizing some obstacles and a speedy way to cover more

ground. But the limitations to this method are our inability to see great distances;

to perceive objects of minimal contrast or small size; to see during the night or low

light and to discern what we see if we are moving rapidly. What one tool or

technology could possibly take all these limitations and mitigate better results?

Infrared Thermal Imaging could and that’s why our airplanes, missiles and space

crafts come fully equipped with IR devices, see example in figure 3.

Figure 3. Aircraft mounted

thermal imaging camera

To rescue an animal in need, it must first be located and this is where IR applications can be beneficial as

shown in figure 4. When it comes to locating injured albatross; oiled auklets or wallowing walrus along vast

lineages of coastline, on open oily oceans or hauled out in vegetative debris – thermal imaging which

captures the heat emitted from all bodies, can for most circumstances well exceed our ocular capabilities for

distance, contrast, acuity, cognition and night vision. Thermal imaging requires zero light and actually visible

light is blocked by the lens which allows only certain wavelengths of infrared radiation to enter the receiving

imager or bolometer. So searching at night when time mandates; when the weather is calmer; when

operations dictate; when survival is the issue or when aircraft are available can be a very positive possibility.

Also, at night because of diurnal cooling, the temperature differences widen between the environmental

background and the objects which emit a consistent temperature (such as a mammal or bird) so this

enhances the contrast of objects in the thermal image sometimes making objects/animals more visible – over

greater distances. The ability to see objects more easily over greater distance is always relative to the size of

the object, the contrast rendered by its emitted temperature, the distance from the object and the atmospheric

attenuation relative to that distance and the sky conditions between the imager and the object such as

moisture, dust, smoke etc.

Figure 4. Left--Grebe thermal detection Mono Lake, CA; Center-- Sea Otter Thermal signature; Right-- Thermal

detection of gulls on the beach Alaska

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

With the advent of other associated tools such as GPS, radio telemetry, cell service, target lock, laser

pointers, thermal paletting and video recording, detection of an animal in need with IR whether from a boat,

raft, airplane, or on-foot, can be quickly and easily documented by location coordinates or pictures or

“pointing” and then rescue and retrieval may follow implemented. The speed and efficiency that birds and

animals may be found can be imperative to their survival. In remote locations transportation resources can

also be in short supply dictating accelerated efforts and pointed accuracy. Infrared also finds people, whether

you are looking for them or not, but can be useful in situational awareness; public safety, poaching operations

or missing crew members.

An important limitation to consider is if the target you are looking for is not giving off heat (homeostasis) or

that heat has diminished to an emitted temperature similar to that of the surrounding environment, you will be

challenged to find the target with IR. Experimental imaging of oil coated wildlife also needs to be done so as

to identify the conductive or insulative property of the coating pollutant and make note of what the thermal

signature of that species, in that condition is for future rescue references.

Assessment and Treatment:

It isn’t any wonder that the horse racing industry has been using thermography on Thoroughbreds for over 25

years – look what those horses are worth! Obviously they deserve the best, but where does that leave us?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved thermal imaging as an acceptable breast screening

modality in the 1980s. Despite worldwide applications and utilization, it seems as though thermal imaging has

yet to make a shadow for itself in veterinary science and medicine. Possibly, as more zoos follow the lead of

San Diego and Berlin, both the diagnostic and monitoring potentialities of IR will be shared and understood.

As a certified medical thermal imaging Technician, the powerful insights and non-invasive practicality of

thermal imaging brings it to a close 2nd behind lifestyle choices for an investment in good health and early

detection.

For assessing health and subsequently diagnosing a condition, the IR camera again captures the emitted

heat as received from the surfical layer of the skin (outer 5mm in Humans) and translates the energy readings

into an image that has a facsimile to the animal or person being read. The heat that is detected is a dutifully

transferred byproduct of our largest organ – the skin- which is tasked with thermoregulation throughout the

body. The activity of small sphincter valves throughout the skin removes excess heat from its subsurface

area of responsibility and transfers it to the outer layers of the skin. This transfer can be so accurate and

detailed that occasionally thermal images can “by coincidence” resemble 3D pictures of internal anatomy. The

heat transfer is a response of the sympathetic nervous system, which unifies the messages from many of the

primary systems of the body such as the nervous system; endocrine system; lymphatic system; circulatory

system; and muscular system. The information consolidated and the message conveyed via the IR

Thermogram is truly a real time road map of a body’s current physiologic activity.

Figure 5. Eagle Image in grey scale. Eagle in rainbow palette. Raven Image in IS palette

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

With color paletting, subtle skin temperature differences become visually apparent, see examples in figure 5.

They may be evaluated as to their relative temperature reading or more generally applied as they relate to the

thermographic symmetry - inherently a part of each body’s birth right. Symmetry as a condition can be altered

permanently or over time, in a biological system, through injury (physical or neurological); structural

misalignment; illness; surgery or pathology. Asymmetrical occurrences - often called anomalies may be

correlated to body locations and temperature differences with adjacent tissue areas. Here we vest in the fact

that “the blood does not lie”. Anomalies which are relatively warmer may be indicative of inflammation,

infection, injury or pathology while relative cooler areas can point to neurological damage; circulatory

deficiencies; severe inflammation or scar tissue.

Applying this then to animal and bird assessments, one need only to incorporate some additional

considerations that will enhance the validity and accuracy of the results. Outermost are the influences or fur,

hair, feathers, scales and shells. Applying heat transfer theory, some of these coverings may be exceptionally

poor conductors of heat from the skin and hence excellent insulators (shell, feathers, fur). What I have seen

so far has been areas of excellent insulation which are still capable of transferring a thermal signature

(readable) to the camera which could be relatively proportional to actual conditions they’re under, while not

being radiometrically correct. Fortunately, when an animal is injured there can be a slight disturbance or

relocation of the normal hair/fur/feather nap in the area. This exterior anomaly in turn can alter the

assessment thermography enough that attention is drawn to the area to make the secondary discovery. This

was the case at the Alaska Zoo when the caribou received their TB shots. I will suggest that every animal and

bird species might have their very own unique thermal signature, likely falling along general patterns of body

form and covering. Also in birds, consistently the largest proportions of heat emitted are from the head and

especially around the eyes, then the legs, followed by the wings to between the shoulder blades. The very

best imaging results and accurate values are achieved when the animal’s exterior is relatively free of dirt and

debris (clean) and especially when they are dry (free of moisture). Moisture tends to alter greatly the

readability of the animal’s thermal signature and it seems unlikely that the wetness is equally-distributed over

the surface at any one time. Imaging river otters in and out of a stream, they were homogenous in

temperature per the camera until patterns of dryness in their pelts developed.

Figure 6. Rehabbing eagles can be a lot of work.

Using thermography as an initial assessment tool will be valuable in research and in setting up data trends

specific to species and circumstance. I don’t suggest that it will surpass palpation, direct observation or blood

work but I do suspect we might begin to find out more than we knew before, if it is applied. In imaging injured

and uninjured wildlife alike – we are more likely to notice bruising, inflammation, infection, small puncture

wounds, broken bones, lack of circulation, head and eye injuries and breathing/nasal imbalances or even

blockages using thermography. Like any other form of imaging, thermography is a screening tool to lead us in

the right direction of closer investigation. Thermography does not diagnose – by law – that is what Doctors

do!

REHABILITATION:

Rehabilitation is an important phase of the Responders process and allows caregivers to take the time

necessary to work directly with the wildlife through care, treatments and controlled conditions, while also

monitoring specific aspects of their health for change. One of the goals of rehabilitation is also to minimize

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

exposure to humans, traumatic procedures and unnatural settings. Using thermography as a tool in this

phase would and could provide for less handling of the “patient” and provide a consistent digital archive of

images monitoring the animals progressive changes, both physiological and physically. Monitoring should be

a non invasive, non biased, consistently applied and well documented. Thermal images would allow

quantitative and qualitative information to be gathered and digitally preserved for analysis at a later date.

Figure 7. Left--Oiled Penguin Center--The washing area Right--Coopers Hawk

Should washing of the wildlife be a part of the rehabilitation effort, thermal imaging can and will play a

premiere role in documenting the effectiveness and the needed follow-up to the cleaning process. Figure 7

shows examples of unwashed birds and the washing process. Because the objective of the wash is to allow

the natural restoration of the animals insulating capacity – monitoring with thermography literally documents

the amount of heat escaping and its locations. This allows for a direct treatment and/or focus on problem

areas as the feather or fur realign for maximum protection. Gathering thermal images of un-oiled, healthy

individuals of each species (eg figure 8), under treatment, would eventually allow for cross referencing

verification of progress and the eventual development of standard criteria for future releases to the wild by

species.

With some of the high end industrial and medical

cameras so portable (a pelican case and about 15

lbs), radiometric Infrared cameras can be taken to

the field or to a transient location of preferable

qualities and make scientific readings accurate to a

1/10 to 1/100th of a degree. Under imaging

protocols, a value change in even a 0.10 of a

degree is any opportunity to monitor subtle

changes over time. Monitoring is such a valuable

tool especially after the initial assessment and first

treatments are made. All too often we fail to critique

the treatments as we move forward and hence their

effectiveness is never truly known. Along with

exceptional sensitivity, most cameras have a 240 X

360 pixel focal plane array which provides digital

Figure 8. Left lateral view of Eagle Thermogram. resolution which is presentable, printable and often

very impressive. Since some cameras can store

images on location - again we have a tool that can not only capture and read infrared emissions to a 0.10 ºF

temperature but they can save them for later quantitative analysis, lab work or apply analytical program tools

with palettes in the field for immediate interpretive results.

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

RECOVERY AND RELEASE:

Documentation and standards pave the way for the ultimate phase of reconciliation for the aided wildlife and

long term guests. The sooner the better for all – but we must be sure. Often we are not sure, but the timing is

right, the lease is running out, the freezer stores are low, the plane is available or the staff is exhausted. To

be sure all that has been done needs to be assimilated in that final confirmation of health, wellness, fitness

and motivation to set free that which was free. Thermal imaging can again in its non-invasive way document

the heat retention capabilities of that short-timers coat or cape. Average body temperature measurements can

be made of the animal and be compared to peers and standards; eyes, head, nostrils, feet, wings – are they

balanced in the amounts of heat emitted and there asymmetries. “Anomaly Free is the Way to Be Free” could

be our motto for the final days of recovery and release. Possibly there are anomalies and asymmetries – but

this bird came that way. We have it documented and the images are

easily referenced. Their personal thermal finger print is on our books

and we can say yea or nay to their departure to the wild.

Should medical surgery, an implanted transmitter or pathological agents

have a part of this animals stay with us - the wound, the scar or the

impacted areas can all be checked via Infrared for abnormal heat which

might be suspect of infection or irritation. Once we are sure, we can

check the battery on the transmitter if it generates heat and set them

free. The release may be sad, but the pictures and thermographs will

Figure 9. Released Eagle gives a

always be great. For they will be the building blocks of better treatments, breathtaking view of a successful

more successful releases and memories of educational proportions. treatment.

CASE HISTORY: INFRARED APPLICATION INVESTIGATION

OCEAN BEAUTY BALD EAGLES

On January 12th 2008, at the Ocean Beauty Seafood cannery in Kodiak, Alaska 50 Bald eagles (Haliaeetus

leucocephalus) were tragically and inadvertently contaminated, injured and/or completely buried in a dump

truck full of oily, slurried, fish by-products. Following an intensive rescue effort, 31 birds survived the injurious

ordeal and were air transported under the direction of the US Fish & Wildlife Service to the cooperative Bird

Treatment and Learning Center (Bird

TLC), 252 miles away in Anchorage,

figure 10. TLC Bird Care is a non-profit

wildlife rehabilitation organization

which treats approximately 1,100 birds

per year and shares urban facilities

with the oil funded Alaska Wildlife

Response Center.

Once in professional care and on the

road to recovery, the oil slurried eagles

were identified, documented,

evaluated, and treated for known

injuries. Blood tests were done to

assess the bird’s internal conditions

and tube feeding of weakened

individuals was deemed vitally

Figure 10. Ocean beauty eagles waiting for a free ride to Anchorage

necessary for re-hydration or nutritional

fortification. Stabilizing the admitted

eagles was next and equally important to their survival. The goal of stabilization is to help mitigate the

negative psychological, physical and physiological stresses endured by the birds prior to rescue and also

while in human care. Stabilization is accomplished through fluids, food/vitamins/antibiotics, radiant heat, quiet

conditions, low lighting, and minimal human contact. The process of stabilization may take several days and

during this time animals are closely monitored for health changes, behavioral indicators, mobility, appetite,

physical strength, alertness and attitude.

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

Once deemed stable, the soiled individuals then proceeded to the infamous washing stations where trained

groups of volunteers and professionals alike washed them in a 105 ºF bath water mixed with 1% Dawn liquid

soap. Both the wash and the rinse cycles can each take 45-60 minutes per bird. Dirty birds are bathed

continuously until the water stays clean and floating oil sheen is not observed. Procedures such as “washing”

are done in earnest and with alignment to rigorous protocols using the current “best practice standards”

accepted both nationally and internationally to remove oil on a wide variety of species. A total of 201 different

species of birds, 9 mammals and 8 reptiles have already benefited from such oil cleansing standardizations

worldwide.

Figure 11. Providing the essentials for our Kodiak Guests

It was at this point in the oiled eagle treatment that the impromptu invitation and investigative opportunity

arose to integrate Thermal Imaging into the rehabilitation process. Aside from the new potential discoveries

we might make, it was agreed and known that my previous IR imaging volunteer work at TLC had

accumulated a sizeable collection of eagle thermograms. With these as potential baseline images of clean,

un-oiled eagles we now could start to build a conceptual comparison of how the images would support our

future interpretation of eagles’ heat loss characteristics and in turn assess how clean and in what locations

the feathers may still be oily. Two thermal imaging visits to Bird TLC took place during the rehabilitation phase

of treatment.

After setting the camera up to the appropriate internal environmental conditions of the TLC Bird Center - we

started to apply the Thermal Imaging Camera as an interpretive tool. Because it equally has the ability to

store large amounts of digital thermal imagery as well as color pictures on it memory card, we were also able

to apply it as a documentation tool – recording times, dates, emitted temperatures and the overall infrared

characteristics of each bird on that visit.

Equipment: The thermal images gathered for investigative study and reference by the attending TLC staff

were taken by a certified Level II FLIR Thermographer using a FLIR P-65 handheld radiometric Imager.

Emissivity was set at 0.98 for consistency among birds and gray scale image palette was used to optimize

focus.

INVESTIGATIVE IMAGING METHODOLOGY

Indoor thermal imaging at Bird TLC:

Lighting indoors overall was fluorescent, minimally reflective and sufficient to see. When imaging throughout

the Bird TLC facility, an escort and the director usually would accompany the Thermographer Eagle to Eagle,

cage to cage. This worked well in most all cases as one person could block cage door and hold the

informational clip board while the other person could encourage and prod the Eagle to adjust their cage

bound posture, profile and or location for the best viewing and imaging. Birds inside the cage were imaged as

individuals – 1 per cage was the norm. With proper focusing of the P-65, the cage wire could be nullified in

the image foreground, making perpendicular imaging through a closed cage door a feasible option, but less

desirable. The preferred view for evaluating the washing process and monitoring rehabilitation was a frontal,

full bird view including head and feet. During this session, a variety of poses and oblique images of the

eagles were taken in an effort to after the fact, select the preferred views for oiled bird rehab IR monitoring

protocol, examples in figure 12. We found the ease of imaging each eagle was almost directly correlated to

the demeanor, comfort and vulnerability of each particular bird. It was also noted that birds with wing or leg

injuries would tend to put the injury to the back of the cage and with great reluctance would they turn or switch

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

sides enough to permit a good view f the injured area. Occasionally there would be a feisty or flighty

individual who would either try to make a break or would get so nervous about the duration of our visit that the

director would dismiss the imaging to keep the bird calm. Occasionally, a more settled or observant eagle

would take note of the metal coated reflective lens on the thermal imager and make obvious jesters and head

motions to track the device more closely- as if intrigued or watching itself in the lens. In a few situations, the

unique configuration or placement of the eagles in their cages, made imaging of the feet impossible due to a

steep imaging angle or not being able to negotiate the bird farther back into its cage for the view.

After setting the camera up to the appropriate

internal environmental conditions of the TLC bird

Center - we started to apply the Thermal Imaging

Camera as an interpretive tool. Because it

equally has the ability to store large amounts of

digital thermal imagery as well as color pictures

on it memory card, we were also able to apply it

as a documentation tool – recording times, dates,

emitted temperatures and the overall infrared

characteristics of that bird at that visit.

Figure 12. Examples of IR imaging of eagles under treatment.

Outdoor thermal imaging at Bird TLC in natural lighting:

Winter outdoor temperatures in Alaska during both Kodiak Eagle imaging sessions were cold, cold, and cold -

usually between -10 º F and +10 º F. The P-65 thermal imager seemed to operate well in this weather, with

the only exception being quicker battery consumption. Meanwhile the Thermographer had to dress for the

weather and give special attention to the uncladden fingertips required to work the controls of the IR camera.

The good thing about the outdoor work was it generally created a steeper thermal gradient between the

eagles themselves and the ambient air temperature – yielding crisper details and stronger contrasts with the

adjoining ambient backdrops. At this point the TLC escorts or director would usually let me float between the

4 or 5 mews or avian holding areas on my own (figure 13), allowing more time to think about the process and

objectives, as well as the capturing of more shots. Usually in each of the mews there would be two to as

many as 5-6 eagles co-habitating. In these situations, even though given the ID numbers of each of the birds

there in – it was nearly impossible to identify them individually as they flew, walked and roosted in a

multiplicity of places and poses during the IR session. But because these eagles had more room to move, it

was easier to reposition my self to get the optimal image angles or capture individual birds side by side for

direct comparisons. All went well imaging within the mews so long as I did not approach the eagles too

closely or move about the enclosure too quickly. In this setting, I could also get improved views of their talons,

especially if they were on peripheral perches. Occasionally, upon entering the mew – one or two individuals

would become uncomfortable with my invasion. Through obvious body gestures I knew a retreat was

necessary to minimize the raucous behavior or reduce the risk of the eagles injuring themselves. In the mews,

heat lamps were occasionally used to comfort those still not ready for the elements. Specific eagles would

then need to be monitored for “sun bathing” as the ability of the externally gathered radiant heat did and

would affect their true thermal signatures for a short duration. This was also true of those eagles who would

sit in direct sunlight within the mews, at certain times of the day.

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

Figure 13. Home sweet home options for Bird TLC guests and their friends.

INVESTIGATIVE IMAGING METHODOLOGY RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVED INDOOR THERMAL IMAGING AT BIRD TLC:

1. Imaging to be done time of day when birds are most settled

2. Image ID # and take color picture prior to thermals of each animal

3. Minimize possibilities of reflective overhead lighting

4. Birds and animals must be relatively clean and thoroughly dry

5. Bandages are best to be removed if possible

6. Full crops after meals should be avoided

7. Shoot through cage bars only when mandated

8. Mirrors may be used to view body areas not easily seen or accessed

9. Establish prioritized view sequence for each species

10. Maintain a consistent 10 degree temperature spread per image

11. Capture all images in grayscale white hot paletting

12. Review and advise on image results before departing Center

13. Store images on an accessible and easily used web based data site for sharing.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVED OUTDOOR THERMAL IMAGING AT BIRD TLC:

1. Imaging to be done time of day when birds are most settled

2. Image ID # and take color picture prior to thermals of each animal

3. Birds and animals must relatively clean and dry

4. Imaging from within the mews is acceptable but imaging portals would be preferred so behavior is not

modified.

5. Capture images of animals alone and with companion animals for comparison.

6. Turn off heat lamps one hour prior to visiting/imaging

7. Full crops after meals to be avoided

8. Bring ample batteries to meet cold day field needs.

9. Imaging to be done when direct sun light does not penetrate the holding area

10. Similar statements as addressed for indoor imaging

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

EXAMPLES OF COMPARATIVE THERMAL IMAGING:

Figures 14 through 17 give IR image examples of methods and techniques discussed in the body of this

manuscript.

Figure 14. Examples of Comparative Thermal Patterns and Delta Temperature Calculations

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

Figure 15. Examples of Undetected Foot Injuries discovered through thermal paletting

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

Figures16. Examples of Avian posing possibilities for optimal infrared imaging, information, monitoring and research.

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

Figure 17. Heat Loss by location and between comparative individuals

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank the IBRRC, the OWCN and the Bird Treatment and Learning Center for their

encouragement, support and all of the great pictures shared to make this manuscript graphic and

comprehensive. And a special thanks to Gary Orlove for his patience.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Judy Reese-Deyoe is a level II FLIR Thermographer, certified Clinical Thermographer and is President of

Raven Infrared. Judy is an Environmental Thermographer and specializes in medical thermography; thermal

animal imaging; airborne wildlife surveys; wild land fire mapping; structural heat loss and environmental

documentation. Judy is the official Thermographer for the Alaska Zoo in Anchorage and frequently provides

thermal imaging for various wildlife groups in Alaska.

For additional information: raveninfrared@aol.com or (907) 262-6547

InfraMation 2008 Proceedings ITC 126 A 2008-05-14

You might also like

- Graphic Storytelling and Visual NarrativeDocument232 pagesGraphic Storytelling and Visual NarrativeTimothy Bussey56% (41)

- Visual DesignDocument35 pagesVisual Designbogarguz33% (6)

- Furuno DS 80 Service ManualDocument52 pagesFuruno DS 80 Service ManualNishant Pandya70% (10)

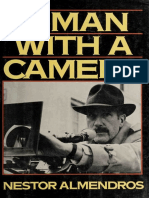

- A Man With A Camera - Almendros, NestorDocument326 pagesA Man With A Camera - Almendros, Nestorakshay kumaresh100% (3)

- Speed Measuring Unit User Manual (ESP-2000-B)Document9 pagesSpeed Measuring Unit User Manual (ESP-2000-B)alexander100% (6)

- BFD-180-570 DN65 GBDocument25 pagesBFD-180-570 DN65 GBalexander100% (3)

- 5srw Program Study PDFDocument6 pages5srw Program Study PDFJoão Paulo67% (3)

- Common Hippopotamus Husbandry GuidelinesDocument105 pagesCommon Hippopotamus Husbandry Guidelinesgabrielwerneck0% (1)

- MAIHAK Shaft Power Meter MDS 840 Manual V1-1Document80 pagesMAIHAK Shaft Power Meter MDS 840 Manual V1-1alexander100% (2)

- Gen4000 Service W455H (Wash Machine)Document100 pagesGen4000 Service W455H (Wash Machine)alexanderNo ratings yet

- SRF HRF SSR DanjouxDocument12 pagesSRF HRF SSR Danjouxalexander100% (1)

- Finding Oil Filled Circuit Breaker Resistance With IRDocument8 pagesFinding Oil Filled Circuit Breaker Resistance With IRalexanderNo ratings yet

- Important Mesurements For IR Surveys in SubstationsDocument7 pagesImportant Mesurements For IR Surveys in SubstationsalexanderNo ratings yet

- Secrets of Bushing Oil Level-GoffDocument8 pagesSecrets of Bushing Oil Level-Goffalexander100% (1)

- IP Video Surveillance. An Essential Guide - Alexandr LytkinDocument196 pagesIP Video Surveillance. An Essential Guide - Alexandr LytkinFahad GhanyNo ratings yet

- Shot AbbreviationsDocument2 pagesShot Abbreviationsapi-356656080No ratings yet

- IR_1Document4 pagesIR_1yanivNo ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S0025326X20301442-mainDocument16 pages1-s2.0-S0025326X20301442-mainBagus Tri AtmojoNo ratings yet

- Preserving Biodiversity - Technology For Biology - SAP InsightsDocument10 pagesPreserving Biodiversity - Technology For Biology - SAP InsightsGabrielle RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Innovation For SARDocument9 pagesInnovation For SARkumarrishabh7102002No ratings yet

- Drones and Risk ManagementDocument2 pagesDrones and Risk Managementrameshkanu1No ratings yet

- Use of Drones in Disaster ManagementDocument3 pagesUse of Drones in Disaster ManagementElsie TupazNo ratings yet

- Santos Ecuatorian Lidar Corrected FormatedDocument29 pagesSantos Ecuatorian Lidar Corrected FormatedJuan MolinaNo ratings yet

- Koh and Wich-2012Document12 pagesKoh and Wich-2012Ryan RamdayalNo ratings yet

- Avian Mortality at Solar Energy Facilities in Southern California: A Preliminary AnalysisDocument28 pagesAvian Mortality at Solar Energy Facilities in Southern California: A Preliminary AnalysisThe Press-Enterprise / pressenterprise.comNo ratings yet

- 2014 597368Document12 pages2014 597368CintiaNo ratings yet

- Applications of thermal imaging in avian scienceDocument13 pagesApplications of thermal imaging in avian scienceTinuszkaNo ratings yet

- C10461183S319 3Document10 pagesC10461183S319 3Habiba AtiqueNo ratings yet

- LANL HB of Radiation Monitoring 3rd Ed. LA-1835 11-1958Document186 pagesLANL HB of Radiation Monitoring 3rd Ed. LA-1835 11-1958DJSeidelNo ratings yet

- Remote Sensing ReefsDocument147 pagesRemote Sensing ReefsRoberto Hernandez-landaNo ratings yet

- LC811 Camera Traps ReportDocument13 pagesLC811 Camera Traps ReportNoThanksNo ratings yet

- Active Fire Detection For Fire Emergency Management: Potential and Limitations For The Operational Use of Remote SensingDocument16 pagesActive Fire Detection For Fire Emergency Management: Potential and Limitations For The Operational Use of Remote Sensingrayen vpNo ratings yet

- Technical Newsletters Agriculture Web 062016Document8 pagesTechnical Newsletters Agriculture Web 062016swatijoshi_niam08No ratings yet

- Active Fire Detection For Fire Emergency ManagemenDocument17 pagesActive Fire Detection For Fire Emergency ManagemenDéborah CelsoNo ratings yet

- Rep 810 INTERVENTION IN THE SITUATION OF CHRONIC AND EMERGENCY EXPOSURE - 063116Document18 pagesRep 810 INTERVENTION IN THE SITUATION OF CHRONIC AND EMERGENCY EXPOSURE - 063116ISHAQNo ratings yet

- Search and Rescue Operation Requirements in GNSS 2Document11 pagesSearch and Rescue Operation Requirements in GNSS 2CaptSameh RashedNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2212827119307978 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S2212827119307978 MainRaheem BaigNo ratings yet

- Nuclear 101 topics on radiation and its applicationsDocument3 pagesNuclear 101 topics on radiation and its applicationsBORA BORANo ratings yet

- Forest Fire Detection Using Computer VisionDocument30 pagesForest Fire Detection Using Computer VisionPRANAV KAKKARNo ratings yet

- Remote Sensing New TecnologyDocument2 pagesRemote Sensing New TecnologyJhéssica VianaNo ratings yet

- Pi-Rard Et Al-2015-Journal of Cosmetic DermatologyDocument7 pagesPi-Rard Et Al-2015-Journal of Cosmetic DermatologyputrisarimelialaNo ratings yet

- IR For Dummies 1999Document6 pagesIR For Dummies 1999Zvonko DamnjanovicNo ratings yet

- Capstone Final Paper Chap 1 5Document93 pagesCapstone Final Paper Chap 1 5BISNAR, Annette Reian S.100% (1)

- Protection From Near-Infrared To Prevent Skin Damage: ArticleDocument7 pagesProtection From Near-Infrared To Prevent Skin Damage: ArticleAsril SenoajiNo ratings yet

- Uses of Radiations in Various FieldsDocument5 pagesUses of Radiations in Various FieldsAdia ChatthaNo ratings yet

- Illegal Dumping InvestigationDocument9 pagesIllegal Dumping InvestigationRetro CosplayNo ratings yet

- Emergency Floating BagDocument10 pagesEmergency Floating BagAman RedhaNo ratings yet

- Sensors 23 03684 v2Document12 pagesSensors 23 03684 v2hani1986yeNo ratings yet

- Remote Sens Ecol Conserv - 2020 - McKellarDocument13 pagesRemote Sens Ecol Conserv - 2020 - McKellarTinuszkaNo ratings yet

- Economic Appraisal of Predator Free Stewart IslandDocument52 pagesEconomic Appraisal of Predator Free Stewart IslandgarethmorgannzNo ratings yet

- Handbook For Radiological MonitorsDocument44 pagesHandbook For Radiological MonitorsChó MèoNo ratings yet

- Infrared Background and Missiles Signature SurveyDocument5 pagesInfrared Background and Missiles Signature Surveyamiry1373No ratings yet

- LoRa Based Ship Man Overboard Rescue System Integrated Long Distance Wireless CommunicationDocument6 pagesLoRa Based Ship Man Overboard Rescue System Integrated Long Distance Wireless CommunicationIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Remote Sensing: Life Signs Detector Using A Drone in Disaster ZonesDocument12 pagesRemote Sensing: Life Signs Detector Using A Drone in Disaster ZonesJuris NuqueNo ratings yet

- A Revw & Inventory of UAS For Detect'n & Monitor'n of Key Biological ResourcesDocument12 pagesA Revw & Inventory of UAS For Detect'n & Monitor'n of Key Biological ResourcesJesus WayneNo ratings yet

- Sip - ContentDocument3 pagesSip - ContentPADERON, JEAN FRANCEL R.No ratings yet

- Emt314 1Document3 pagesEmt314 1Ehigie promiseNo ratings yet

- Activity 2 STSDocument4 pagesActivity 2 STSVince Andrei MayoNo ratings yet

- Engineering Solutions To Prevent or Minimize Impacts: Next SlideDocument4 pagesEngineering Solutions To Prevent or Minimize Impacts: Next SlideMarkAllenPascualNo ratings yet

- Work Method Statement and Safety ConceptsDocument35 pagesWork Method Statement and Safety ConceptsnadeemNo ratings yet

- The Lixiscope Portable Accident Department: Device: of Its in The andDocument4 pagesThe Lixiscope Portable Accident Department: Device: of Its in The andعايد التعزيNo ratings yet

- WWF Camera Trap Final PDFDocument181 pagesWWF Camera Trap Final PDFDiego JesusNo ratings yet

- Practical Applications ofDocument43 pagesPractical Applications ofLouigie DagonNo ratings yet

- 12 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument106 pages12 - Chapter 2 PDFGizachew Zeleke100% (1)

- AWR-930W Unit 1 Lesson 6: Levels of EmergenciesDocument2 pagesAWR-930W Unit 1 Lesson 6: Levels of EmergenciesMagnifico DionicioNo ratings yet

- Automating Insect Monitoring Using Unsupervised Near Infrared SensorsDocument11 pagesAutomating Insect Monitoring Using Unsupervised Near Infrared SensorsKikoNo ratings yet

- An Ultra-Wideband High-Dynamic Range GPR For Detecting Buried People After Collapse of BuildingsDocument6 pagesAn Ultra-Wideband High-Dynamic Range GPR For Detecting Buried People After Collapse of Buildingslpgx1962No ratings yet

- Abstracts-of-Presentations-2021-TWS-Drone-Symposium-as-of-1Jul21Document9 pagesAbstracts-of-Presentations-2021-TWS-Drone-Symposium-as-of-1Jul21TinuszkaNo ratings yet

- 1stproposal ConceptPaperDocument5 pages1stproposal ConceptPapergrayisahayNo ratings yet

- IRT Home Work Assignment 1 16Document1 pageIRT Home Work Assignment 1 16Trần Vĩnh TrúcNo ratings yet

- By NaanaDocument29 pagesBy Naanajuicypine14No ratings yet

- Herpetological Bulletin: Number 106 - Winter 2008Document45 pagesHerpetological Bulletin: Number 106 - Winter 2008Umair AneesNo ratings yet

- Automatic Detection, Tracking and Counting of Birds in Marine Video ContentDocument6 pagesAutomatic Detection, Tracking and Counting of Birds in Marine Video ContentJulio ArticaNo ratings yet

- Schraft & Clark, 2019Document7 pagesSchraft & Clark, 2019Beatriz BritoNo ratings yet

- Model Number StructureDocument12 pagesModel Number StructurealexanderNo ratings yet

- DSC 60Document132 pagesDSC 60alexanderNo ratings yet

- Ecdis Ec 1000: With Conning DisplayDocument184 pagesEcdis Ec 1000: With Conning DisplayalexanderNo ratings yet

- EC1000 Conning&interfaceDocument198 pagesEC1000 Conning&interfacealexanderNo ratings yet

- DS 30Document148 pagesDS 30alexanderNo ratings yet

- Stem Cell Use in Surgical Treatment of Tennis Elbow-SandickDocument8 pagesStem Cell Use in Surgical Treatment of Tennis Elbow-SandickalexanderNo ratings yet

- IR NDT On Aeronautical Plastics-Flores-BolarinDocument8 pagesIR NDT On Aeronautical Plastics-Flores-BolarinalexanderNo ratings yet

- IR For Triage in Emergency Medical Services-BrioschiDocument12 pagesIR For Triage in Emergency Medical Services-BrioschialexanderNo ratings yet

- IR Theromgraphy in The NFL-GarzaDocument8 pagesIR Theromgraphy in The NFL-GarzaalexanderNo ratings yet

- Breast Thermography and Clinical Applications-MostovoyDocument6 pagesBreast Thermography and Clinical Applications-MostovoyalexanderNo ratings yet

- Thermography PrimerDocument28 pagesThermography PrimerR. Mega MahmudiaNo ratings yet

- NETA Thermal Testing Criteria for Electrical EquipmentDocument1 pageNETA Thermal Testing Criteria for Electrical EquipmentalexanderNo ratings yet

- IR Thermography in Sand Minining-BlanchDocument4 pagesIR Thermography in Sand Minining-BlanchalexanderNo ratings yet

- IR Imaging in Engineering Applications - HuntDocument8 pagesIR Imaging in Engineering Applications - HuntalexanderNo ratings yet

- Lock in Thermography of Plasma Facing Components-Courtois ADocument12 pagesLock in Thermography of Plasma Facing Components-Courtois AalexanderNo ratings yet

- High Speed IR For Machinability-Arriola AldamizDocument10 pagesHigh Speed IR For Machinability-Arriola AldamizalexanderNo ratings yet

- IR Theromgraphy in The NFL-GarzaDocument8 pagesIR Theromgraphy in The NFL-GarzaalexanderNo ratings yet

- IR Benefits-Thinking Outside The Box - BlackDocument12 pagesIR Benefits-Thinking Outside The Box - BlackalexanderNo ratings yet

- Infrared Techniques for Condition Assessment of Isolated Phase Bus DuctDocument6 pagesInfrared Techniques for Condition Assessment of Isolated Phase Bus DuctalexanderNo ratings yet

- Guess The Real World Emissivity-DeMonteDocument14 pagesGuess The Real World Emissivity-DeMontealexanderNo ratings yet

- Framing Photographs, Denying Archives: The Difficulty of Focusing On Archival PhotographsDocument18 pagesFraming Photographs, Denying Archives: The Difficulty of Focusing On Archival PhotographsGross EduardNo ratings yet

- Physics EntertainmentDocument124 pagesPhysics EntertainmentthryeeNo ratings yet

- Camera TimelineDocument1 pageCamera Timelineapi-278315005No ratings yet

- Solved Paper BVCLSDocument25 pagesSolved Paper BVCLSsanya narangNo ratings yet

- Amateur Photographer - 26 September 2020Document68 pagesAmateur Photographer - 26 September 2020Andres RoldanNo ratings yet

- Late Night Talking - Harry Styles AnalysisDocument2 pagesLate Night Talking - Harry Styles AnalysisMolly MillsNo ratings yet

- ASME V Art 22 RT PDFDocument136 pagesASME V Art 22 RT PDFKhalidMoutaraji100% (1)

- Corona Renderer Feature ListDocument6 pagesCorona Renderer Feature Listzidan zidanNo ratings yet

- Describe A Photo You Took That You Are Proud ofDocument3 pagesDescribe A Photo You Took That You Are Proud ofDespair TheNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 4 PhotogrammetryDocument48 pagesCHAPTER 4 Photogrammetryaduyekirkosu1scribdNo ratings yet

- Unit 10: Sitcom: How Much Do You Want? Scene 1Document2 pagesUnit 10: Sitcom: How Much Do You Want? Scene 1Alex SantosNo ratings yet

- Berenice Abbott - New Guide To Better Photography-Crown Publishers (1953) PDFDocument280 pagesBerenice Abbott - New Guide To Better Photography-Crown Publishers (1953) PDFZdravkoMicanovicNo ratings yet

- Contoh Soalan Exam Spa9: Kefahaman Bahasa InggerisDocument6 pagesContoh Soalan Exam Spa9: Kefahaman Bahasa InggerisMuhammad Fakruhayat Ab RashidNo ratings yet

- Directors Statement - Sam MckeownDocument8 pagesDirectors Statement - Sam MckeownSam McKeownNo ratings yet

- LiarDocument2 pagesLiarShinadeWilkieNo ratings yet

- CV Ankit Shandilya Media Production SkillsDocument1 pageCV Ankit Shandilya Media Production SkillsAnkit ShandilyaNo ratings yet

- Cme Standard For Colo Completion Picture Report - Bts Outdoor TypeDocument9 pagesCme Standard For Colo Completion Picture Report - Bts Outdoor TypeHarisa Dinda MerinaNo ratings yet

- International Speech ContestDocument7 pagesInternational Speech ContestVaibhav VernekarNo ratings yet

- Đề chọn đt hsg hhtDocument30 pagesĐề chọn đt hsg hhtNguyễn Quốc HuyNo ratings yet

- Video 19: Oil PastelsDocument9 pagesVideo 19: Oil PastelsMARCOSFERRAZZNo ratings yet

- IVSA Program 18 JuneDocument101 pagesIVSA Program 18 JuneberoizapNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument239 pagesUntitledDonia GhaithNo ratings yet

- (1206) PinterestDocument1 page(1206) PinterestMohamed Abou El hassanNo ratings yet

- Astm - E1382 PDFDocument24 pagesAstm - E1382 PDFGowtham Vishvakarma100% (1)