Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Offffprinted Ffrom Modern Language Review: Volume 112, Part 1 JANUARY 2017

Offffprinted Ffrom Modern Language Review: Volume 112, Part 1 JANUARY 2017

Uploaded by

Klir0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views4 pagesOriginal Title

Книга 02.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views4 pagesOffffprinted Ffrom Modern Language Review: Volume 112, Part 1 JANUARY 2017

Offffprinted Ffrom Modern Language Review: Volume 112, Part 1 JANUARY 2017

Uploaded by

KlirCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Offprinted from

MODERN LANGUAGE REVIEW

VOLUME 112 , PART 1

JANUARY 2017

© Modern Humanities Research Association

Reviews

close textual readings and a steady sense of history. e study reveals how

the de- piction of Borges has changed over time, responding to different

historical/political junctures. It maps a sure path through the complex and

labyrinthine nature both of Borges’s own work and of the critical, oen highly

polemical, responses to Borges, with one scholar, Beatriz Sarlo, offering particular

guidance. For it was Sarlo, and colleagues such as Ricardo Piglia, who, during and

aer the military dictatorship in Argentina, encouraged critics to think

through and beyond such Manichaean categories as Europe/Argentina,

elite/popular, placing Borges in the productive, liminal, space of ‘las orillas’, on the

borders between genres, languages, and cul- tures. A particularly fruitful application

of Sarlo’s insights comes in Chapter , ‘El desaforado caminador’, which explores

how Borges fictionalized and mythologized the streets of Buenos Aires and how, in

turn, ‘the figure of Borges is constructed and narrated in the life and spaces of the

city’ (p. ). e entire study turns on the observation made by Borges in

the aerword to his book of stories, El Hacedor (), which speaks of a man

who sets out to draw a world. He peoples it for many years with kingdoms and

mountains before discovering at the end of his life that the ‘patient labyrinth of lines

traces the lineaments of his own face’. Draw the world that is Argentina, this

book convincingly demonstrates, and the face of Borges will always appear, will

always be appropriated and disputed.

As I write these lines in May , I read that the pope has recently quoted a

line from Borges’s s ‘urban’ poetry—analysed in Chapter —in his apostolic

exhortation ‘Amoris Laetitia’. Media sources have unearthed a photograph—the

focus of Chapter —from , when Borges travelled to Santa Fe to give a class on

gauchesque literature at a Jesuit school at the invitation of a young scholar, Jorge

Bergoglio, who, many years later, would be elected pope. e handshake

between Borges and a shy, baby-faced priest, captured in a photograph now travelling

across the world, points to the enduring relevance of this fascinating study.

U W J K

e Child in Spanish Cinema. By S W. Manchester: Manchester University

Press. . viii+ pp. £. ISBN ––––.

Given the child’s perennial presence in Spanish cinema since its inception, it may

come as some surprise to those not working on the topic that Sarah Wright’s

book is the first monograph to treat this expansive and vital subject. Wright’s

excellent book does not simply fill a heretofore glaring gap in scholarship on the

child in film, both more generally and in the (particularly rich) Spanish context.

It also provides valuable insights into the ways Spain’s cinema continually turns

to the child in order to work through the legacies of the nation’s violent and

authoritarian past, to reflect new political, social, and economic realities that arise

in its present, and to forge investment in the child’s symbolic futurity.

Admirably wide-ranging—in terms both of the genres and periods of films it

explores and of the theoretical and critical frameworks it adopts to examine them

—

e Child in Spanish Cinema is a foundational text for the field, demonstrating

MLR, .,

how Spanish film alternately brings the child to life (as child, but also as doll,

as monster, as automaton) and condemns the child to death on screen. Wright

tackles the daunting task of addressing the child’s central role in several decades

of Spanish cinema with impressive economy, condensing her treatment into

four chapters plus an Introduction. Aer an overview of the book’s arguments

and what Wright mod- estly terms a ‘brief, imperfect, potted pre-history of the

child in Spanish cinema up to the s’ (p. ) the four chapters move in

broad chronological strokes, each centred on a key theme, performer, or motif

of the respective historical moment, varied in scope and diverse in theoretical

framing.

Chapter takes on the child in the cine religioso of the s, pivoting

around the film Marcelino, pan y vino (dir. Ladislao Vajda, ) and its

figuration (and celebration) of the child’s death as glorious sacrifice under

Francoism. Its engage- ment with the repeated trope of the dead, helpless, or

orphaned (boy) child links up the historical realities of both early Francoist

National Catholic ideology and the incipient consumerism of the desarrollismo

years, and a final section on the voice and dubbing shows how in bringing the

child to life as loving automaton, this cinema might also be robbing him of his

own breath and voice (p. ). Chapter centres on child star Marisol (Pepa

Flores) and the intense, troubling, public scrutiny of her child’s (and later,

woman’s) body as she grew up in and was metaphorized by the public sphere

under both dictatorship and democracy. Employing theories of trauma and

cultural amnesia, it traces the repetition of Marisol’s function as exchange

commodity (living doll) passed between older men, unfolding several parallel

analyses to further problematize uses of children and their bodies in Spanish

film.

Chapter takes Víctor Erice’s iconic El espíritu de la colmena as a

lens through which to read the child’s gaze—and the child as object of the gaze

—in art- house and horror cinema from the end of Francoism to the present. It

proposes that the child in this film (and its inheritors) can help spectators

recuperate historical memory or work through the traumatic past by generating

what Alison Landsberg has called ‘prosthetic memory’—a key concept for

Wright, who dely negotiates its contradictions throughout. Looking at the

child’s connection to the monstrous, and the child as monster, it shows how the

‘child and the Spanish Civil War’ genre is both reified and deconstructed in recent

films. e final chapter explores adoles- cents in contemporary cinema,

focusing close attention on two films exemplifying ‘wound culture’ (see Mark

Seltzer, ‘Wound Culture: Trauma in the Pathological Public Sphere’, October,

(Spring ), –) in Spain’s cinema of the present century. Reading

Achero Mañas’s child-abuse film El Bola alongside Camino, Javier

Fesser’s cancer drama-cum-Opus Dei critique, the chapter examines marks

le on adolescents’ skin as well as how their bodies’ on-screen abuse can

engage the viewer in an ethical relationship to the child. In circular fashion, we

return through Camino to the martyrdom of the child seen in Chapter ,

revealing the lingering legacies of Francoism that persist down to the present

day.

Much of the book speaks to this re-emergence of the past in the present via the

figure of the child. While theoretical approaches relating to (historical) memory

Reviews

and its recuperation predominate in the book, Wright also carves out space for

a variety of rich parallel analyses using a range of theories from Film Studies,

psychoanalysis, and queer theory, among others. e multiplicity of

approaches mirrors the book’s multiple children: across this diverse material,

Wright resists the impulse to claim that the child is or does one particular thing

in Spain’s cinema.

e study will therefore be of great value to scholars and students of

Spanish culture and film, not only as a survey of the child’s presence therein but

also as an engaging series of creatively theorized close readings that enrich

understanding of films canonical and otherwise.

B U S T

e Foreign Passion/La pasión extranjera. By C A. Trans. by B B.

London: Influx Press. pp. £.. ISBN ––––.

Since the s, Argentinian poetry has been a major point of reference

across the Hispanic world. e combined impact of political turmoil

and openness to cultural avant-gardes has resulted in a potent tradition that

ranges from inter- nationally acclaimed authors such as Juan Gelman or

Alejandra Pizarnik to the neobarroco experiments of Osvaldo Lamborghini or

Néstor Perlongher, and to the younger generations of authors that bridge past and

present, such as Fabián Casas, Washington Cucurto, and Martín Gambarotta.

However, as Ben Bollig rightly argues (pp. –) in the Prologue to this book,

this creative diversity has not been reflected in a balanced circulation and recep-

tion. Authors based in the provinces—what is usually called ‘el interior’, the

inland territories—tend to receive less attention than those who work from the

main literary cities, in a clear example of that tension between ‘centre’ and

‘periphery’ studied by Pascale Casanova and Franco Moretti, among many others.

e work of the poet Cristian Aliaga (b. ), born in Buenos Aires

but based in the southern region of Patagonia, has been marked by this spatial

imbalance, which Bollig calls ‘a form of internal exile’ (p. ). Logically, space

plays a central role in Aliaga’s poetry, as the expression of political and economic

practices that shape both human and physical landscape. is concern is

palpably clear in e Foreign Passion, which emerged aer a visiting

professorship that Aliaga took at the University of Leeds in . In fact, the

book’s structure resembles a travelogue or a travel diary, as every text is rooted in a

geographical reference—most of them in the north of England, but occasionally in

continental Europe. In this process of travel and displacement, Aliaga isolates spaces

and reworks them, turning them into a set of symbols: children playing in a military

museum embody the unex- pectedness of war, while a pub and its multiple

micro-scenes become a parable of resistance against the hardships of daily life.

Bollig suggests a certain affinity (p. ) with the ‘harshness’ and ‘brutality’ of

omas Bernhard’s e Voice Imitator, although the fiercely

monotonous and grinding voice of the Austrian is replaced here by a disposition

for wonder: events

You might also like

- Documents of West Indian HistoryDocument14 pagesDocuments of West Indian Historykarmele91No ratings yet

- Geography Paper 1 HLSL MarkschemeDocument14 pagesGeography Paper 1 HLSL MarkschemeVikram DevanathanNo ratings yet

- 2017 Evaluation of The Marginal and Internal Discrepancies of CAD-CAM Endocrowns With Different Cavity DepthsDocument7 pages2017 Evaluation of The Marginal and Internal Discrepancies of CAD-CAM Endocrowns With Different Cavity Depthsitzel lopezNo ratings yet

- Balnço de Estudos Utopicos No BRASILDocument21 pagesBalnço de Estudos Utopicos No BRASILElza TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Cangoma Calling Spirits and Rhythms of FDocument27 pagesCangoma Calling Spirits and Rhythms of Fmyahaya692No ratings yet

- Affect and Realism in Contemporary Brazilian FictionFrom EverandAffect and Realism in Contemporary Brazilian FictionNo ratings yet

- RESEÑA. LA NOVELA DE LA REVOLUCION MEXICANA. ANTONIO CASTRO LEAL. 1958. Idioma InglesDocument2 pagesRESEÑA. LA NOVELA DE LA REVOLUCION MEXICANA. ANTONIO CASTRO LEAL. 1958. Idioma InglespapeleritoNo ratings yet

- Trajectories of Empire: Transhispanic Reflections on the African DiasporaFrom EverandTrajectories of Empire: Transhispanic Reflections on the African DiasporaJerome C. BrancheNo ratings yet

- Statement of Teaching Interests and Research: TH THDocument4 pagesStatement of Teaching Interests and Research: TH THJuan Antonio HernandezNo ratings yet

- Inherited Exile and The Work of María Rosa Lojo: Studies in 20th & 21st Century LiteratureDocument21 pagesInherited Exile and The Work of María Rosa Lojo: Studies in 20th & 21st Century LiteraturecarlosNo ratings yet

- Rappaport Utopias InterculturalesDocument8 pagesRappaport Utopias InterculturalesIOMIAMARIANo ratings yet

- Brazilian PostcolonialitiesDocument155 pagesBrazilian PostcolonialitiesCarol Cantarino100% (1)

- Contemporary Literary Genre: Contemporary Literature Is A QuarterlyDocument11 pagesContemporary Literary Genre: Contemporary Literature Is A QuarterlyMe-AnneLucañasBertiz100% (2)

- The Space In-Between Essays On Latin American Culture (Silviano Santiago)Document197 pagesThe Space In-Between Essays On Latin American Culture (Silviano Santiago)Alexandra ErdosNo ratings yet

- The History in The TextDocument4 pagesThe History in The Texttrivium206100% (2)

- Ethics of Liberation in The Age of GlobaDocument3 pagesEthics of Liberation in The Age of GlobaDiogo FidelesNo ratings yet

- Transpoetic Exchange: Haroldo de Campos, Octavio Paz, and Other Multiversal DialoguesFrom EverandTranspoetic Exchange: Haroldo de Campos, Octavio Paz, and Other Multiversal DialoguesMarília LibrandiNo ratings yet

- Klaud AbDocument5 pagesKlaud AbJoycel ManabatNo ratings yet

- Persistence of Folly: On the Origins of German Dramatic LiteratureFrom EverandPersistence of Folly: On the Origins of German Dramatic LiteratureNo ratings yet

- 3 - John Beverley - The Margin at The Center (On Testimonio)Document19 pages3 - John Beverley - The Margin at The Center (On Testimonio)js back upNo ratings yet

- 1986 3206 1 PBDocument26 pages1986 3206 1 PBnpNo ratings yet

- Colloquium AbstractsDocument9 pagesColloquium AbstractsΝότης ΤουφεξήςNo ratings yet

- Allegory and NationDocument26 pagesAllegory and NationJavier RamírezNo ratings yet

- Philippines and Its Grandeur's MetamorphosisDocument5 pagesPhilippines and Its Grandeur's MetamorphosisRangerbackNo ratings yet

- An Immodest Proposal For Literary StudiesDocument10 pagesAn Immodest Proposal For Literary StudiesMaria Cristina FloresNo ratings yet

- Adorno, Rolena - New Perspectives in Colonial Spanish American Literary StudiesDocument20 pagesAdorno, Rolena - New Perspectives in Colonial Spanish American Literary StudiesStranger NoneNo ratings yet

- An Integration Paper For Survey of Philippine LiteraturesDocument10 pagesAn Integration Paper For Survey of Philippine Literatureseugene_slytherin1556No ratings yet

- The Literary Work and Values Education Two Texts and ContextsDocument7 pagesThe Literary Work and Values Education Two Texts and ContextsDana Elysse Madulid100% (1)

- English Afro-Diasporic Imaginaries PDFDocument6 pagesEnglish Afro-Diasporic Imaginaries PDFMichel Mingote Ferreira de AzaraNo ratings yet

- History and GenresDocument8 pagesHistory and GenresBrylle CapiliNo ratings yet

- Baroque PDFDocument0 pagesBaroque PDFLary BagsNo ratings yet

- Discovering and Re-Discovering Brazilian Science Fiction: An OverviewDocument27 pagesDiscovering and Re-Discovering Brazilian Science Fiction: An OverviewPedro FortunatoNo ratings yet

- Flamenco Passion Politics and Popular CuDocument2 pagesFlamenco Passion Politics and Popular Cue.agaslangeNo ratings yet

- The Literary Work and Values EducationDocument6 pagesThe Literary Work and Values EducationBrandon Perez100% (1)

- Jackson, Three Glad RacesDocument24 pagesJackson, Three Glad Racesjeronimo_pizarroNo ratings yet

- 6790 19260 1 PBDocument18 pages6790 19260 1 PBTomNo ratings yet

- Cel 347100392Document31 pagesCel 347100392cel resuentoNo ratings yet

- CartuchoDocument21 pagesCartuchocesarsandNo ratings yet

- Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural StudiesDocument19 pagesArizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural StudiesfauzanrasipNo ratings yet

- Anna RZEPKA, Natalia CZOPEK: WstępDocument27 pagesAnna RZEPKA, Natalia CZOPEK: WstępBengt HörbergNo ratings yet

- Librepensador Progressive Thoughts in The Writings of Vicente Sotto, 1900-1915Document61 pagesLibrepensador Progressive Thoughts in The Writings of Vicente Sotto, 1900-1915Rufus Casiño MontecalvoNo ratings yet

- Historia de La LIJ Crítica (Interesante)Document11 pagesHistoria de La LIJ Crítica (Interesante)JesusMNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Literature and the Public Sphere: From the Plantation to the PostcolonialFrom EverandCaribbean Literature and the Public Sphere: From the Plantation to the PostcolonialRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Current Critical Perspectives in Literature, Film, and Cultural StudiesDocument6 pagesCurrent Critical Perspectives in Literature, Film, and Cultural StudiesIrma LiteNo ratings yet

- Hau Laughter in NoliDocument8 pagesHau Laughter in NoliSalimNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Pre Colonial To ContemporaryDocument10 pages21st Century Pre Colonial To ContemporaryaroseollagueNo ratings yet

- Martínez Ethnographic WritingDocument20 pagesMartínez Ethnographic Writingfm fmNo ratings yet

- M2. 21st Century Lit Phil and WorldDocument6 pagesM2. 21st Century Lit Phil and WorldErickson SongcalNo ratings yet

- Introduction To PhilippineDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Philippinesaramina CandidatoNo ratings yet

- Transpacific Connections: Literary and Cultural Production by and about Latin American NikkeijinFrom EverandTranspacific Connections: Literary and Cultural Production by and about Latin American NikkeijinMaja ZawierzeniecNo ratings yet

- American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese HispaniaDocument3 pagesAmerican Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese HispaniaLis AraújoNo ratings yet

- A Portrait of The Present: Sergio Chejfec's Photographic Realism.Document23 pagesA Portrait of The Present: Sergio Chejfec's Photographic Realism.Luz HorneNo ratings yet

- Monsters by Trade: Slave Traffickers in Modern Spanish Literature and CultureFrom EverandMonsters by Trade: Slave Traffickers in Modern Spanish Literature and CultureNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 21st LitDocument21 pagesLesson 6 21st LitAllen TicarNo ratings yet

- A Note From Editor of Diliman ReviewDocument22 pagesA Note From Editor of Diliman Reviewjack thegoodNo ratings yet

- Owen Hilary and Anna M Klobucka Eds Gender EmpireDocument3 pagesOwen Hilary and Anna M Klobucka Eds Gender EmpireEduardo da CruzNo ratings yet

- 14 - Aesthetics: Modernismo and Vanguardismo, Which in Spite of Their Strong European InfluencesDocument8 pages14 - Aesthetics: Modernismo and Vanguardismo, Which in Spite of Their Strong European InfluencesPatrick DoveNo ratings yet

- Supplemental Lecture FinalsDocument26 pagesSupplemental Lecture FinalsREYCY JUSTICE JOY VASQUEZNo ratings yet

- The Fabrication of New Cultural HeroesDocument27 pagesThe Fabrication of New Cultural HeroesGuillermo Molina MoralesNo ratings yet

- Art 02Document12 pagesArt 02ImpregnadorNo ratings yet

- Shipwreck in the Early Modern Hispanic WorldFrom EverandShipwreck in the Early Modern Hispanic WorldCarrie L. RuizNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Letter 101/3/2020: Introduction To Research Methodology For Law and Criminal JusticeDocument19 pagesTutorial Letter 101/3/2020: Introduction To Research Methodology For Law and Criminal JusticeMichelle UngererNo ratings yet

- Special Publication No.3 of The Society For Geology Applied To Mineral DepositsDocument416 pagesSpecial Publication No.3 of The Society For Geology Applied To Mineral Depositskiss dalmaNo ratings yet

- CVS 215 - Course OutlineDocument2 pagesCVS 215 - Course OutlineBenard Omondi100% (1)

- FINAL - PHD Brochure 02 July 2021 UpdatedDocument402 pagesFINAL - PHD Brochure 02 July 2021 UpdatedIkshvaku ShyamNo ratings yet

- ISO 31010 Risk Assessment Techniques TableDocument3 pagesISO 31010 Risk Assessment Techniques Tablemohamed sobhyNo ratings yet

- Far04410 PDFDocument9 pagesFar04410 PDFAlfred FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Pink Simple School NewsletterDocument4 pagesPink Simple School NewsletterCarla Flor LosiñadaNo ratings yet

- Competency: Employ Variety of Strategies For Effective Interpersonal CommunicationDocument5 pagesCompetency: Employ Variety of Strategies For Effective Interpersonal CommunicationJaymar MagtibayNo ratings yet

- Body Language Week 7Document16 pagesBody Language Week 7carlosNo ratings yet

- Physical Geography 12 Weather and Climate Unit Plan Lesson PlansDocument28 pagesPhysical Geography 12 Weather and Climate Unit Plan Lesson Plansapi-499589514No ratings yet

- D420 7656Document8 pagesD420 7656D IZomer Oyola-GuzmánNo ratings yet

- L10 Data Report Student's Name: Lab Section:: Your Data May Have More or Fewer Cycles Than The 7 Allotted in TheDocument7 pagesL10 Data Report Student's Name: Lab Section:: Your Data May Have More or Fewer Cycles Than The 7 Allotted in ThehiviNo ratings yet

- Bill Harvey On Arch FailuresDocument8 pagesBill Harvey On Arch FailuresChuck NorrieNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan For Mathematics 4Document3 pagesLesson Plan For Mathematics 4Nathaniel RemendadoNo ratings yet

- OEP a262A7EDocument2 pagesOEP a262A7EPaoloNo ratings yet

- Spelling Rubric - Within Writing: Advanced Proficient Proficient Approaching Proficiency NoviceDocument1 pageSpelling Rubric - Within Writing: Advanced Proficient Proficient Approaching Proficiency NoviceYani anggraeniNo ratings yet

- Politically Incorrect Guide To ScienceDocument274 pagesPolitically Incorrect Guide To ScienceAgnieszka WisniewskaNo ratings yet

- 2013 Vcaa Physics Exam Solutionsv2 PDFDocument4 pages2013 Vcaa Physics Exam Solutionsv2 PDForhanaliuNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Evolutionary Game Theory and Its Applications - Fundamentals of Evolutionary Game Theory and Its Applications (PDFDrive)Document223 pagesFundamentals of Evolutionary Game Theory and Its Applications - Fundamentals of Evolutionary Game Theory and Its Applications (PDFDrive)Montes Gerald D.100% (1)

- Unit-4 Symbolism of ColoursDocument15 pagesUnit-4 Symbolism of ColoursЧулуунбаатар БаасанжаргалNo ratings yet

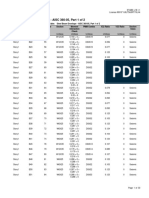

- Tabla de RatioDocument33 pagesTabla de RatioLuis Antonio GuerraNo ratings yet

- ML-UP 3ed Quiz U. 1 StudentsDocument4 pagesML-UP 3ed Quiz U. 1 StudentsНикита ЛунтовскийNo ratings yet

- (21st Century Skills Library - Animal Invaders) Barbara A. Somervill - Gray Squirrel-Cherry Lake Publishing (2008) PDFDocument36 pages(21st Century Skills Library - Animal Invaders) Barbara A. Somervill - Gray Squirrel-Cherry Lake Publishing (2008) PDFmisterNo ratings yet

- Takehome - Exam DiD and RDDDocument36 pagesTakehome - Exam DiD and RDDAlejandro Moral ArandaNo ratings yet

- School ID 415509 Region 2 Division Isabela District South School Name Ameci School Year 2017-2018 Grade Level 9 Section ArchaeopteryxDocument17 pagesSchool ID 415509 Region 2 Division Isabela District South School Name Ameci School Year 2017-2018 Grade Level 9 Section ArchaeopteryxCamille ManaloNo ratings yet

- STS Finals ReviewerDocument31 pagesSTS Finals ReviewerFranchezka NapayNo ratings yet

- PDF 1Document302 pagesPDF 1LuckyNo ratings yet

- Ufc+3 220 01 PDFDocument183 pagesUfc+3 220 01 PDFNicolas Fuentes Von KieslingNo ratings yet