Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Osteoporosis in Men Suspect Secondary Disease First

Uploaded by

megatOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Osteoporosis in Men Suspect Secondary Disease First

Uploaded by

megatCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW

ANGELO LICATA, MD, PhD*

CME

CREDIT

Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes,

and Metabolism, The Cleveland Clinic

Osteoporosis in men:

Suspect secondary disease first

■ A B S T R AC T ONTRARY TO POPULAR NOTIONS, osteo-

C porosis is a disease not only of women. In

Since osteoporosis in men is more often secondary rather fact, men account for about 20% of cases of

than primary (idiopathic), we need to seek the underlying osteoporosis and 25% of hip fractures.

cause through the history and laboratory testing. Treatment But there are differences. The conse-

options are similar to those for women, although data are quences are worse for men than for women.

limited about their efficacy in men. Compared with women, men with hip frac-

tures have higher rates of mortality and mor-

■ KEY POINTS bidity.1,2 More are institutionalized, and 30%

to 50% die within a year of fracture vs about

Prevention is the best approach to treatment of osteoporosis 20% of women.

in men, given the limited options at the moment. Another difference of note: from 50% to

70% of cases of osteoporosis in men are sec-

Glucocorticoids top the list of drugs that can cause ondary to another condition, whereas osteo-

osteoporosis. Prescribe a bisphosphonate prophylactically porosis in women is usually primary (idiopath-

when starting long-term glucocorticoid therapy. ic). Hence, in assessing a man, we should

think of secondary osteoporosis first and pri-

mary second.

Bone densitometry can be problematic in men, as the T Many advances have occurred in the past

score is often indexed to a reference database in young decade, including increased awareness of

women. Men are currently not covered for reimbursement osteoporosis, the technology to diagnose it in

under the Bone Mass Measurement Act, but they should its early, asymptomatic stage, and many new

undergo densitometry as women do. treatments. Osteoporosis is now viewed as a

treatable disease, rather than as an inevitable

The biochemical evaluation tends to be more extensive in consequence of aging. Unfortunately, aware-

men with osteoporosis because the bone loss is usually ness of osteoporosis in men lags behind that in

secondary to another condition. The younger the male women, as do research and rates of detection

patient, the more important the laboratory evaluation. and treatment.

This article outlines the unique features

of osteoporosis in men, including its patho-

Alendronate has been shown to increase skeletal density in physiology, causes, diagnosis, and treat-

men comparably to levels seen in women. It is now ment.

approved for use in men. Teriparatide, a parathyroid

hormone preparation, is now approved to increase bone ■ BIMODAL PREVALENCE BY AGE

mass in men with primary or hypogonadal osteoporosis at

high risk for fracture. The prevalence of osteoporosis by age in men

and in women is quite different (FIGURE 1).

*Theauthor has indicated that he has received grant or research support from Merck, Lilly, Pfizer,

Whereas in women the distribution of osteo-

Aventis, Wyeth Ayerst, and Novartis corporations. This paper discusses treatment that is not porosis with age is skewed toward the later

approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the use under discussion. years, in men many cases occur before age 50,

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003 247

OSTEOPOROSIS IN MEN LICATA

Ascertainment bias. Fewer men than

Distribution of osteoporosis cases women undergo bone density measurement,

by age in men and women leading to the incorrect conclusion that men

do not get osteoporosis. However, the third

40

National Health and Nutrition Examination

Men Women Survey,3 using T-score criteria, found that

Percent of total cases

30

28% to 47% of men over age 50 have

osteopenia at the femoral neck, and 36%

have osteoporosis. For a 50-year-old man, the

20 lifetime risk for any fracture of the femur, ver-

tebrae, or distal forearm ranges from 13% to

50%.3

10

■ PRIMARY OSTEOPOROSIS

MAY BE DIFFERENT IN MEN

0

<40 41-50 51-60 61-70 71-80 81-90 >90 Primary osteoporosis is often ascribed to aging.

Some believe that in men it results from tra-

Age (years)

becular thinning rather than from trabecular

FIGURE 1. In women most cases of osteoporosis occur destruction, as seen in women.4

in the later years; in men the distribution is bimodal. With age, a variety of metabolic and

The early peak is mostly due to secondary osteoporosis, endocrine changes combine to weaken the

while the later peak mostly represents primary skeleton.5–10 Production of testosterone and

osteoporosis. growth hormone decreases, and muscles dete-

riorate. Calcium absorption becomes ineffi-

cient. Secondary hyperparathyroidism arises.

with a second peak in the later years. The Ambient parathyroid hormone levels are

Glucocorticoids cases early in life in men tend to be secondary higher in older than in younger patients.

osteoporosis and the later cases tend to be pri- Varying degrees of vitamin D dysfunction

attack the mary, although this is not always true. may be seen, from ineffective function to

skeleton on deficiency.

■ WHY FEWER MEN GET OSTEOPOROSIS

two fronts ■ CAUSES OF SECONDARY OSTEOPOROSIS

Although men do get osteoporosis, they have

a lower prevalence than women, for several Many diseases and drugs can cause secondary

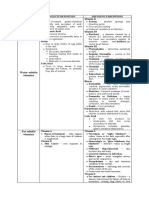

reasons: osteoporosis (TABLE 1).

Men accumulate more bone mass dur-

ing the peak growth years, making the adult Drug-induced bone loss

male skeleton generally stronger. They also Glucocorticoids top the list of drugs that

accumulate more muscle mass during puber- can cause osteoporosis. Although oral gluco-

ty, which contributes to skeletal strength. corticoids are the major culprits, potent

Men do not go through menopause. Male inhaled glucocorticoids may also have sys-

hormone production does not abruptly cease. temic effects on the skeleton.11

Instead, testosterone levels decline slowly Excessive doses of glucocorticoids have

throughout life unless there is an abrupt many bad effects on calcium and bone metab-

change (eg, due to surgical or chemical olism.12 They blunt intestinal calcium absorp-

orchiectomy). tion directly, even with adequate serum levels

Life expectancy for men has been short- of vitamin D, and secondary hyperparathy-

er than for women, so that primary osteoporo- roidism develops. Osteoclasts increase their

sis had less time to develop and cause fragility activity, and skeletal turnover increases. The

fractures. However, more men are now living drugs also directly blunt osteoblastic activity,

long enough to develop primary osteoporosis. thus attacking skeletal integrity on two fronts.

248 CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003

Renal tubulopathy and calciuria develop (a TA B L E 1

direct effect of the steroids), drawing calcium

from the body and exaggerating the hyper- Causes of secondary osteoporosis

parathyroid state. Sex steroid production Drugs

declines by suppression of gonadal function Alcohol

Anticonvulsants

and pituitary gonadotropin secretion. Antigonadotropins

However, many other drugs can cause Glucocorticoids (oral, inhaled)

osteopenia, osteoporosis, and osteomalacia,13 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

including: Thyroxine

• Anticonvulsants, which enhance vita- Tobacco

min D metabolism and cause calcium malab- Endocrine

sorption and secondary hyperparathyroidism Acromegaly

• Antigonadotropic drugs used in treating Hypercortisolism

Hyperparathyroidism

prostate cancer are known to cause osteope- Hyperprolactinemia

nia, but the true incidence of clinical osteo- Hyperthyroidism

porosis and fracture rates is not known. Hypogonadism

Tobacco and alcohol are both directly Gastrointestinal

toxic to the skeleton. Alcohol use is an inde- Cirrhosis

pendent risk factor for osteoporosis.14 It sup- Inflammatory bowel disease

presses osteoblast activity: intake of as little as Malabsorption

50 g (four standard drinks) per day causes a Genetic and metabolic

dose-dependent decrease in osteocalcin, a Homocystinuria

marker of osteoblastic activity. Higher intakes Hypophosphatasia

(>100 g/day) used for years cause decreased Marfan syndrome

Osteogenesis imperfecta

skeletal mass.15 However, moderate drinking

is not deleterious. Neoplastic

Anemia (vitamin B12 deficiency, thalassemia)

Leukemia

Gastrointestinal diseases Myeloma, benign gammopathies

Gastrointestinal diseases such as primary liver

disease (with or without cirrhosis), ulcers Neurologic

Disuse syndrome

requiring gastrectomy, inflammatory bowel Glucocorticoid, adrenocorticotropin therapy for myasthenia

disease, pancreatic insufficiency, and malab- gravis, multiple sclerosis

sorptive problems cause osteoporosis and, at Immobilization

times, osteomalacia.16–19 Alcoholic cirrhosis, Muscle atrophy

primary biliary cirrhosis, and steroid-treated Paralysis

autoimmune hepatitis lead more to osteoporo- Pulmonary

sis than to osteomalacia. Cystic fibrosis

Drug therapy for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Hypercalciuria:

Hyperabsorptive or renal tubular? Renal

Hypercalciuria, with or without stone disease, Chronic renal failure, dialysis

Mineral-losing tubulopathies

is found in 20% of men with osteoporosis eval- Stone disease

uated in our clinic. Often, it is occult and is

not associated with overt stone disease. In my Transplantation bone disease

Lung, liver, heart, kidney

experience, patients with latent calciuria may

have normal calcium excretion because their

calcium intake is low, but if you give them a

calcium supplement for a week and remeasure The hyperabsorptive problem is associated

their calcium excretion, it will be high. with increased or high-normal levels of 1,25

Both hyperabsorptive hypercalciuria and dihydroxyvitamin D. This above-normal level

renal tubular hypercalciuria (renal leak) are increases bone metabolism and, consequently,

associated with osteopenia and osteoporosis. skeletal loss.20–24

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003 249

OSTEOPOROSIS IN MEN LICATA

In renal tubular hypercalciuria, initially Primary hyperthyroidism is an unlikely

there is a failure to reclaim urinary calcium, cause of osteoporosis because it is usually diag-

and serum levels decline. A sustained com- nosed long before it can destroy the skeleton.

pensatory rise in serum parathyroid hormone The real concern is exogenous hyperthy-

corrects this drop in calcium at the expense of roidism caused by thyroxine supplementation

increased bone turnover. that suppresses thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Renal tubular acidosis is another entity to However, this should not be a clinically signif-

be mindful of.25 icant issue now that we have sensitive assays

for thyroid-stimulating hormone, bone densit-

Endocrine disorders ometry, and therapy to counteract bone loss.

Several endocrine disorders are well-known Acromegaly can lead to osteoporosis para-

causes of osteoporosis. The clinical challenge doxically, apparently when a growing pituitary

is when they occur in an atypical or occult tumor produces less gonadotropin, thus sup-

fashion. pressing testosterone synthesis.

Hypogonadism during puberty is an estab-

lished cause of adult skeletal deficiency, pri- Other causes

marily as it inhibits the development of peak Plasma cell dyscrasias cause osteoporosis

bone mass.26–28 In a young patient, replace- or osteopenia.

ment of sex steroids may reverse the problem. Multiple myeloma and even benign mon-

Abrupt hypogonadism in adult men fol- oclonal gammopathy increase bone

lowing chemical or surgical orchiectomy (eg, turnover.30 This skeletal effect arises from

for the treatment of prostate cancer)29 is increased osteoclastic activity due to the elab-

comparable to menopause in women and is oration of cytokines within the bone marrow.

equally destructive to the skeleton. On the The degree to which these disorders are occult

other hand, the milder forms of hypogo- and go undiagnosed determines the extent of

nadism of aging have not been shown to skeletal destruction.

cause bone loss. Leukemia may also be associated with

Fracture may be Hyperparathyroidism causes bone bone destruction if sufficiently occult and

the only destruction, although skeletal problems such chronic.31

as osteitis fibrosis cystica are rare nowadays Benign hematologic disorders such as

presenting because this disorder is usually discovered thalassemia and vitamin B12 deficiency also

early in routine health care evaluations and contribute to bone loss.32,33

feature in some laboratory testing. More than 80% of patients Focal metastatic disease causes local bone

men with occult with hyperparathyroidism have no symptoms, destruction, not systemic osteoporosis.

however. Secondary and tertiary hyper- Humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy is

endocrine parathyroidism of renal disease is not a diag- not a clinically significant cause of osteoporo-

disorders nostic challenge, but it is often overlooked, sis, since it portends a short prognosis.

even in patients on renal dialysis. Genetic or metabolic disorders known to

Endogenous hypercortisolism can pre- cause osteoporosis or osteopenia include

sent atypically. About 5% of patients present homocystinuria, Marfan syndrome, hypophos-

with osteoporosis and never show the typical phatasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta.34–37 A

features of cortisol excess, such as centripetal family history of any skeletal disorder should

obesity, aberrant deposition of fat, diabetes raise our suspicion, although the rarity of

mellitus, or hypertension. Fractures may be many of these disorders makes them less likely

the only presenting characteristic. considerations in general medical practice.

Hyperprolactinemia in men is insidious.

Unrecognized, it decreases testosterone pro- ■ BONE DENSITOMETRY AND T SCORES

duction and libido and in theory can cause

osteoporosis. Whether fractures develop, how- Bone densitometry is the greatest single

ever, depends on other issues, such as chronic- advance that has made possible the awareness,

ity of the disorder, initial peak bone mass, and diagnosis, and early treatment of osteoporosis.

traumatic events. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry of the spine

250 CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003

and hip can detect osteoporosis in women and TA B L E 2

men quite early in its course.

I believe that bone density evaluation Diagnostic evaluation

should be mandatory for men after age 60 or of osteoporosis in men

65 if there is no specific history of unex- History

plained fracture, and certainly before this age Family history

in any man with a history of low trauma frac- Past medical history (secondary causes identifiable)

ture. Guidelines for its use are likely to be the Health habits (use of alcohol or tobacco, lack of exercise)

same for men as for women, although this has Drug use (bone-toxic agents)

not been clearly delineated. Physical examination

Unfortunately, although the federal Bone Signs of specific diseases

Mass Measurement Act requires Medicare to

pay for bone density measurements for women Initial laboratory evaluation

within certain guidelines, men have not yet Complete blood cell count

Complete chemical profile

been included. One hopes that Congress will

Parathyroid hormone

rectify this omission. 25 vitamin D

24-hour urinary calcium

Caveats about T scores

The T score, used to determine the risk for Follow-up laboratory evaluation

fracture in women, is also used in men, but Urine cortisol

Serum testosterone

with a caveat: a male data base must be used

Protein electrophoresis of serum

for deriving the score. Serum growth hormone

Recall that the T score is the number of Insulin-like growth factor 1

standard deviations (SD) below or above the Prolactin

mean value in a reference population. If a

female data base is used, only 3% to 5% of

men have osteoporosis, whereas 30% of men

over age 50 have osteopenia or osteoporosis Do not

when a male data base is used. Hence, a male dard deviations below the mean) are at greater

data base is mandatory for accurate diagnosis risk than people with higher scores, but the withhold

of osteoporosis in men. score alone does not diagnose osteoporosis: treatment until

The definitions of disease by T scores are the clinician diagnoses osteoporosis on the

the same for men as for women. A T score of basis of the personal and family history, phys- the T score

2.5 or more standard deviations (SD) below ical examination, laboratory values, and bone reaches an

the mean (ie, < –2.5 SD) is classified as osteo- densitometry.

porosis. (Remember that these are negative arbitrary

numbers, so –3.5 is less than –2.5.) A T score ■ CLINICAL AND LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS number

of –1.5 to –2.5 is classified as osteopenia, and OF OSTEOPOROSIS IN MEN

a T score of –1.5 or higher is normal.

But T scores should only be considered as In men, we should consider primary osteo-

guidelines for detection of osteoporosis. porosis only after ruling out a specific cause. In

Treatment should not be withheld until a women, too, we should never assume that

patient’s T score reaches a specific level. osteoporosis is primary: the high incidence of

Rather, the diagnosis and decision to treat primary disease in women often obscures con-

should be based on clinical criteria. sideration of secondary causes, but secondary

Sometimes, treatment should be started before causes do exist and need to be considered.

the T score declines to –2.5, for example, in

patients taking glucocorticosteroids. History and physical examination

Moreover, there is no “safe” T score, ie, no In most men with osteoporosis, the history

discrete cutoff for “osteoporosis” or “no osteo- raises the suspicion of a possible cause, which

porosis.” The scores are a continuum of frac- is then pursued with appropriate laboratory

ture risk. People with lower scores (more stan- and radiologic testing (TABLE 2).

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003 251

OSTEOPOROSIS IN MEN LICATA

A family history of osteoporosis is as ing, tetracycline-labeled biopsy of the skeleton

important a consideration in men as it is in might be helpful. Histologic study may show

women. Osteoporosis in family members is a unexpected findings, such as hematologic dis-

risk factor, especially in families with a ten- ease or osteomalacia. In our clinical experi-

dency toward small, thin stature. In addition, ence, however, biopsy has not proven as help-

pediatric data show similarities in bone densi- ful as laboratory or clinical data. Nonetheless,

ty of parents and their children.38,39 it should be kept in mind, such as in a patient

The physical examination may reveal with a continuing history of fractures or bone

cushingoid features, acromegaly, or hypogo- pain and no obviously abnormal laboratory

nadism, or evidence of blood dyscrasias or can- tests.

cer, liver disease, or pathognomonic skeletal

abnormalities. ■ TREATING SECONDARY

OSTEOPOROSIS IN MEN

Laboratory testing more extensive in men

The biochemical evaluation tends to be more Treating osteoporosis in men usually implies

extensive in men with osteoporosis because treating the underlying cause. The

the bone loss is usually secondary to another reversibility of osteoporosis after the under-

condition. The younger the male patient, the lying cause is controlled or eliminated

more important the laboratory evaluation. depends on the degree of bone damage.

A tiered evaluation is recommended, pro- Treatment of hypercortisolism, hyper-

ceeding from routine to more exotic metabol- parathyroidism, acromegaly, or hyperpro-

ic and endocrine tests. lactinemia can reverse bone loss to varying

Routine biochemical profiles and a com- degrees. Resolution of a deficiency, such as

plete blood cell count may reveal suspicious hypogonadism or vitamin D deficiency, may

findings that should be evaluated further, such be all that is needed.

as abnormalities in calcium, phosphorus, other Skeletal disease due to intestinal or drug-

electrolytes, alkaline phosphatase, liver or kid- induced malabsorption often responds well to

Measure 24- ney function, and blood counts. calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

hour calcium Routine urine testing for 24-hour excre- Drug-related bone loss should, in theory,

tion of calcium is suggested initially in all men respond to stopping the drug, but this may not

excretion in all because hypercalciuria is common. Levels of be easy. For example, the therapeutic need for

men with urinary phosphorus and other substances, such glucocorticoids may preclude stopping them.

as amino acids or sugars, may be evaluated Fortunately, the bisphosphonates alendronate

osteoporosis later if there is suspicion of renal tubulopathy (Fosamax) and risedronate (Actonel) are

and associated bone disease. available for patients using glucocorticoids,

Measurement of parathyroid hormone and and these two drugs should be prescribed pro-

25-hydroxyvitamin D may uncover subtle sec- phylactically when chronic steroid treatment

ondary hyperparathyroidism or vitamin D is started.

deficiency. Thiazide diuretics can stop renal calcium

In rare cases, evaluation for hypophos- loss and reverse skeletal deficiency to varying

phatasia, homocystinuria, or osteogenesis degrees.

imperfecta might be needed. Evaluate for Treatment of various neoplastic diseases

hypophosphatasia in patients with fracture may control the skeletal disease and fractures

and low serum alkaline phosphatase. Evaluate attending these illnesses, but additional bone-

for homocystinuria in those with physical fea- specific therapies are often needed.

tures and a history of fracture. Evaluate for

osteogenesis imperfecta in those with a family ■ TREATING IDIOPATHIC

history, fracture as a child, and physical fea- OSTEOPOROSIS IN MEN

tures.

Idiopathic osteoporosis in men was not satis-

Skeletal biopsy factorily treated until the recent approval of

If no abnormality is found on laboratory test- alendronate for use in men.

252 CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003

Nonpharmacologic measures high cost and parenteral route of administra-

Nonpharmacologic measures alone are not tion are limitations to its widespread use,

sufficient. Nevertheless, calcium and vitamin however.

D supplementation and exercise should be

part of any treatment program for men. A Sodium fluoride

healthy lifestyle with smoking cessation and Sodium fluoride has long been used in women

limited use of alcohol is as important in men as an osteoblastic stimulator, and most studies

as it is in women. of its efficacy have been in women. Its use in

men has not been fully evaluated, but there

Hormonal therapy are limited studies.50 Unfortunately, the safety

Testosterone therapy is marginally effec- margin is narrow.51 In women, excessive doses

tive in the hypogonadism of aging but is more produce dense but poor-quality bone that is

effective in hypogonadism of younger prone to fracture.

men.40,41

Estradiol has been found, in a few rare Bisphosphonates

cases, to have a positive effect on the male Alendronate is the first drug to show effi-

skeleton, although the true clinical signifi- cacy in men in a well-controlled trial, increas-

cance of this is not yet known.42,43 ing skeletal density comparably to levels seen

Calcitonin has not undergone any large in women. Its effects do not appear to depend

studies in men with primary osteoporosis, on testosterone levels. The study was not sta-

although small increases in bone density and a tistically powered to evaluate the efficacy of

reduction in vertebral fractures were seen in fracture reduction, but a tendency in that

major studies in women.44 direction was noted.52

Parathyroid hormone increases skeletal Etidronate in cyclical regimens is used in

density in men,45 but its full potential has not women and, theoretically, should help men.

been explored. A commercial product, teri- Risedronate should also be beneficial.53–55

paratide (Forteo), has received FDA approval

for use in men and women.46 ■ PREVENTION IS BEST TREATMENT Calcium,

Growth hormone increases bone density

in patients with adult growth hormone defi- The take-home message is essentially the

vitamin D,

ciency.47 Since growth hormone secretion same as that for women: prevention is better exercise are

decreases with aging, its use has theoretical than treatment, given the limited treatment

merit in the treatment of osteoporosis.48,49 Its options at the moment.

part of any

treatment plan

■ REFERENCES

1. Diamond TH, Thornley SW, Sekel R, Smerdely P. Hip frac- 8. Gallagher JC, Kinyamu HK, Fowler SE, Dawson-Hughes B, in men

ture in elderly men; prognostic factors and outcomes. Med Dalsky GP, Sherman SS. Calciotropic hormones in bone

J Aust 1997; 167:412–415. markers in the elderly. J Bone Miner Res 1998;

2. Center JN, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman 13:475–482.

JA. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture 9. Lau KH, Baylink DJ. Vitamin D therapy of osteoporosis:

in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 1999; plain vitamin D therapy vs active vitamin D analog (D-hor-

353:878–882. mone) therapy. Calcif Tissue Int 1999; 65:296–306.

3. Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston CC, et al. Prevalence of 10. Orwoll ES, Meier DE. Alterations in calcium, vitamin D in

low femoral bone density in older US adults from the parathyroid hormone physiology in normal men with

NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 1997; 12:1761–1783. aging: relationship to the development of senile osteope-

4. Jaron JJ, Makins NB, Sagreiya K. The microanatomy of tra- nia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986; 63:1262–1269.

becular bone loss in normal aging men and women. Clin 11. Lipworth BJ. Systemic adverse effects of inhaled cortico-

Orthop 1987; 215:260–271. steroid therapy: a systematic review and meta analysis.

5. Portale AA, Lonergan ET, Tanney D, Halloran BP. Aging Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:941–955.

alters calcium regulation of serum concentration of 12. Zaqqa D, Jackson R. Diagnosis and treatment of glucocorti-

parathyroid hormone in healthy men. Am J Physiol 1997; coid-induced osteoporosis. Cleve Clin J Med 1999; 63:221–230.

272:139–146. 13. Tannirandom P, Epstein S. Drug-induced bone loss.

6. Cahaupey MC, Durr F, Chapui P. Age-related changes in Osteoporos Int 2000; 11:637–659.

parathyroid hormone and 25 hydroxy cholecalciferol lev- 14. Turner RT. Skeletal response to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp

els. J Gerontol 1983; 38: 19–22. Res 2000; 24:1693–1701.

7. Haden ST, Brown VM, Hurwitz S, Scott J, El-Elajj FG. The 15. Diamond T, Stiel D, Lunzer ML, et al. Ethanol reduces

effects of Asian gender on parathyroid hormone dynam- bone formation and may cause osteoporosis. Am J Med

ics. Clin Endocrinol 2000; 52:329–338. 1989; 86:282–288.

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003 253

OSTEOPOROSIS IN MEN LICATA

16. Valentine F, Snisky CA. Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in 18:48–51.

patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 38. Ferrari S, Rizzoli R, Slosman D, Bonjour TP. Familial resemblance for

94:878–883. bone mineral mass is expressed before puberty. J Clin Endocrinol

17. Vasquez H, Mazure R, Gonzalez D, et al. Risk of fractures in celiac dis- Metab 1998; 83:358–361.

ease patients: a cross-sectional, case control study. Am J 39. Lonzer MD, Imrie R, Rogers D, Worley D, Licata A. Effects of heredity,

Gastroenterol 2000; 95:183–189. age, weight, puberty, activity, and calcium intake on bone mineral

18. Vleggaar FP, VanBuuren HR, Wolfhagen FH, Schalm SW, Pols HA. density in children. Clin Pediatr 1996; 35:185–189.

Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. 40. Finkelstein JS, Klibanski A, Neer RM, et al. Increase in bone density

Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 11:617–621. during treatment of men with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogo-

19. McCaughan W, Feller RB. Osteoporosis in chronic liver disease: patho- nadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84:1966–1975.

genesis, risk factors and management. Dig Dis 1994; 12:223–231. 41. Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, et al. Effect of testosterone treat-

20. Borghi L, Meschi T, Guerra A, et al. Vertebral mineral content in diet- ment on bone mineral density in men over 65 years of age. J Clin

dependent and diet-independent hypercalciuria. J Urol 1991; Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84:1966–1972.

146:1334–1338. 42. Slemenda CW, Longcope C, Zhou L, et al. Sex steroids and bone mass

21. Bataille P, Achard JM, Fournier A, et al. Diet, vitamin D, and vertebral in older men; positive associations with serum estrogens and negative

mineral density in hypercalciuric calcium stone formers. Kidney Int associations with androgens. J Clin Invest 1997; 100:1755–1759.

1991; 39:1193–1205. 43. Smith EP, Boyd J, Frank GR, et al. Estrogen resistance caused by a

22. Ghazali A, Fuentes V, Desanaint C, et al. Low bone marrow density mutation in the estrogen receptor gene in a man. N Engl J Med 1994;

and peripheral blood monocyte activation profile in calcium stone 331:1059–1061.

formers with idiopathic hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 44. Chesnut CH 3rd, Silverman S, Andriano K, et al. A randomized trial of

82:32–38. nasal spray salmon calcitonin in postmenopausal women with estab-

23. Audran M, Legrand E. Hypercalciuria. Joint Bone Spine 2000; lished osteoporosis. PROOF Study Group. Am J Med 2000;

67:509–515. 109:267–276.

24. Pietschrnann F, Bleslau NA, Pak CY. Reduced vertebral bone density 45. Slovik DM, Rosenthal DI, Doppelt SH, et al. Restoration of spinal bone

in hypercalciuric nephrolithiasis. J Bone Miner Res 1992; 7:1383–1388. in osteoporotic men by treatment with human parathyroid hormone

25. Domrongkitchaiporn S, Pongsakul C, Stitchantrakul W, et al. Bone (1-34) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Bone Miner Res 1986;

mineral density and histology in distal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney 1:377–381.

Int 2001; 59:1086–1093. 46. Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hor-

26. Finkelstein JS, Neer RM, Biller B, et al. Osteopenia in men with a his- mone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in post-

tory of delayed puberty. N Engl J Med 1992; 226:600–604. menopausal women osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2001; 19:1434–1441.

27. Finkelstein JS, Klibanski A, Neer RM. A longitudinal evaluation of 47. Ho KK, Hoffman DM. Aging and growth hormone. Horm Res 1993;

bone mineral density in adult men with histories of delayed puberty. 40:80–86.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:1152–1155. 48. Lissett CA, Shalet SM. Effects of growth hormone on bone and mus-

28. Berteloni S, Baroncelli G, Battini R, et al. Short-term effective testos- cle. Growth Horm IGF Res 2000; 10(suppl B):95–101.

terone treatment from reduced bone density in boys with constitu- 49. Baurn BM, Biller BMK, Finkelstein JS, et al. Effect of physiological

tional delay of puberty. J Bone Miner Res 1995; 10:140–148. growth hormone therapy on bone density and body composition in

29. Daniell HW. Osteoporosis after orchiectomy for prostate cancer. J patients with adult onset growth hormone deficiency: a randomized

Urol 1997; 157:439–444. placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1996; 125:883–890.

30. Pecherstorfer M, Seibel MJ, Woitge HW, et al. Bone resorption in 50. Ringe JD, Rovaati LC. Treatment of osteoporosis in men with fluoride

multiple myeloma and in monoclonal gamrnopathy of undetermined alone or in combination with bisphosphonates. Calcif Tissue Int 2001;

significance: quantification by urinary pyridinium links of collagen. 69:252–255.

Blood 1997; 103:743–750. 51. Ringe JD, Rovati LC. Treatment of osteoporosis in men with fluoride

31. Hoorweg-Numan J, Kardos G, Roos JC, et al. Bone mineral density alone or in combination with bisphosphonates. Calcif Tissue Int 2001;

and markers of bone turnover in young adult survivors of childhood 69:252–255.

lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Endocrinol 1999; 50:227–244. 52. Orwoll E, Ettinger M, Weiss S, et al. Alendronate for the treatment of

32. Wonke B, Jensen C, Hanslip JJ, et al. Genetic and acquired predispos- osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 604–610.

ing factors in treatment of osteoporosis and thalassemia major. J 53. Haguenauer D, Welch V, Shea B, Tugwell P, Adachi JD, Wells G.

Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 1998; 11:795–801. Fluoride for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporotic fractures:

33. Goerss JB, Kim CH, Atkinson EJ, et al. Risk of fractures in patients a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2000; 11:727–738.

with pernicious anemia. J Bone Miner Res 1992; 7:573–579. 54. Cortet B, Vasseur J, Grardel B, et al. Management of male osteo-

34. Brenton DP, Dow CJ. Homocystinuria and Marfan syndrome: a com- porosis. Joint Bone Spine 2001; 68:252–256.

parison. J Bone Joint Surg 1972; 54:277–298. 55. Miller PD, Watts NB, Licata AA, et al. Cyclical etidronate in the treat-

35. Magid D, Pyeritz R, Fishman EK. Musculoskeletal manifestations of ment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: efficacy and safety after seven

the Marfan syndrome. Am J Roentgenol 1990; 155:99–104. years of treatment. Am J Med 1997; 103:468–476.

36. Weinstein RS, Whyte MP. Management of adult hypophosphatasia:

report of severe and mild cases. Arch Intern Med 1981; 141:727–731. ADDRESS: Angelo Licata, MD, PhD, Department of Endocrinology,

37. Bischoff H, Freitag P, Jundt G, Steinmann B, Tyndall A, Theiler R. Type Diabetes, and Metabolism, A30, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, 9500

1 osteogenesis imperfecta: diagnostic difficulties. Clin Rheumatol 1999; Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44195.

INTERNAL

INTERNAL Clinical vignettes and questions on the differential

diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions

MEDICINE

MEDICINE likely to be encountered on the Qualifying IN THIS ISSUE

BOARD

BOARD Examination in Medicine — as well as in practice. PAGE 192

Take the challenge.

REVIEW

REVIEW

254 CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 70 • NUMBER 3 MARCH 2003

You might also like

- Osteoporosis: How To Treat Osteoporosis: How To Prevent Osteoporosis: Along With Nutrition, Diet And Exercise For OsteoporosisFrom EverandOsteoporosis: How To Treat Osteoporosis: How To Prevent Osteoporosis: Along With Nutrition, Diet And Exercise For OsteoporosisNo ratings yet

- 2014 OsteoporosisInMen ThematicReport EnglishDocument24 pages2014 OsteoporosisInMen ThematicReport EnglishTatia TsnobiladzeNo ratings yet

- Mayo Clinic Guide to Preventing & Treating Osteoporosis: Keeping Your Bones Healthy and Strong to Reduce Your Risk of FractureFrom EverandMayo Clinic Guide to Preventing & Treating Osteoporosis: Keeping Your Bones Healthy and Strong to Reduce Your Risk of FractureRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- New and Developing Pharmacotherapy For Osteoporosis in Men: Expert Opinion On PharmacotherapyDocument13 pagesNew and Developing Pharmacotherapy For Osteoporosis in Men: Expert Opinion On Pharmacotherapyarber mulolliNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis Men 10Document7 pagesOsteoporosis Men 10Claudia IrimieNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis in The Aging Male: Treatment Options: BackgroundDocument16 pagesOsteoporosis in The Aging Male: Treatment Options: BackgroundcumbredinNo ratings yet

- The Pharmacological Management of OsteoporosisDocument6 pagesThe Pharmacological Management of Osteoporosisarber mulolliNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis Self-Tool (OST) and Other Interventions At: Rural Promising Practice Issue BriefDocument6 pagesOsteoporosis Self-Tool (OST) and Other Interventions At: Rural Promising Practice Issue Briefaldex10No ratings yet

- Osteoprosis PDFDocument6 pagesOsteoprosis PDFsaeed hasan saeedNo ratings yet

- OsteoporosisDocument8 pagesOsteoporosisSoraya FadhilahNo ratings yet

- Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoporosis: A Brief ReviewDocument7 pagesScreening, Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoporosis: A Brief ReviewraffellaNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis A ReviewDocument8 pagesOsteoporosis A ReviewAliza MustafaNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis: Best PracticeDocument7 pagesOsteoporosis: Best PracticePerez Wahyu PurnasariNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis: The Increasing Role of The Orthopaedist: ClassificationDocument10 pagesOsteoporosis: The Increasing Role of The Orthopaedist: ClassificationMila RevalinaNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis A ReviewDocument8 pagesOsteoporosis A ReviewIga AmanyzNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis and Periodontal Disease: History and Physical ExaminationDocument15 pagesOsteoporosis and Periodontal Disease: History and Physical ExaminationYenniy IsmullahNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis: A Review: June 2016Document8 pagesOsteoporosis: A Review: June 2016Yolan TiaraNo ratings yet

- 2018 Update On OsteoporosisDocument16 pages2018 Update On OsteoporosisManel PopescuNo ratings yet

- What Is Osteoporosis?: Osteoposis Is A Disease ofDocument48 pagesWhat Is Osteoporosis?: Osteoposis Is A Disease ofTaruna GargNo ratings yet

- AAFP - Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis PDFDocument10 pagesAAFP - Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis PDFEvelyn LeonieNo ratings yet

- The Worldwide Problem of Osteoporosis: Insights Afforded by EpidemiologyDocument7 pagesThe Worldwide Problem of Osteoporosis: Insights Afforded by EpidemiologymgobiNo ratings yet

- A Review On Some Physiological Studies Related To OsteoporosisDocument14 pagesA Review On Some Physiological Studies Related To OsteoporosisAndy KumarNo ratings yet

- Health Teaching Plan - OsteoporosisDocument9 pagesHealth Teaching Plan - OsteoporosisAudrie Allyson Gabales100% (2)

- OsteoporosisDocument12 pagesOsteoporosisAzharul Islam ArjuNo ratings yet

- Orthopedic May 2013Document11 pagesOrthopedic May 2013javi222222No ratings yet

- Menopause: Medical Author: Medical EditorDocument4 pagesMenopause: Medical Author: Medical EditorJanethcita SencaraNo ratings yet

- Div Class Title Diet Nutrition and The Prevention of Osteoporosis DivDocument17 pagesDiv Class Title Diet Nutrition and The Prevention of Osteoporosis DivLucas Oliveira MouraNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis: Current Concepts: Ibrahim Akkawi Hassan ZmerlyDocument6 pagesOsteoporosis: Current Concepts: Ibrahim Akkawi Hassan ZmerlyDimas M IlhamNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis GTDocument15 pagesOsteoporosis GTZelalem AbrhamNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis The Evolution in DiagnosisDocument12 pagesOsteoporosis The Evolution in DiagnosisPakistan RevolutionNo ratings yet

- General - OsteoporosisDocument9 pagesGeneral - OsteoporosisAsma NazNo ratings yet

- Shoolar Ederly OsteoDocument9 pagesShoolar Ederly OsteoBayu Surya AwalludinNo ratings yet

- Anchala Mahilange - jemds-ORADocument4 pagesAnchala Mahilange - jemds-ORAdrpklalNo ratings yet

- 1042 FullDocument9 pages1042 Fulloki harisandiNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Low Bone Density or Osteoporosis To Prevent Fractures in Men and Women: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update From The American College of PhysiciansDocument28 pagesTreatment of Low Bone Density or Osteoporosis To Prevent Fractures in Men and Women: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update From The American College of PhysiciansRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Osteoarthritis in Women: Effects of Estrogen, Obesity and Physical ActivityDocument15 pagesOsteoarthritis in Women: Effects of Estrogen, Obesity and Physical ActivitypakemainmainNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis PaperDocument7 pagesOsteoporosis Paperapi-558387899No ratings yet

- Osteoporosis in Older AdultsDocument12 pagesOsteoporosis in Older AdultsJuan Diego Sandoval RojasNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis PHD ThesisDocument5 pagesOsteoporosis PHD Thesislizsimswashington100% (2)

- Osteoporosis Essay ThesisDocument8 pagesOsteoporosis Essay Thesisnatalieparnellcolumbia100% (2)

- Osteoporosis PEDocument51 pagesOsteoporosis PENitin BansalNo ratings yet

- Patogenesis Osteoporosis V PDFDocument15 pagesPatogenesis Osteoporosis V PDFaji pangestuNo ratings yet

- Patogenesis Osteoporosis VDocument15 pagesPatogenesis Osteoporosis Vaji pangestuNo ratings yet

- Nutrition and Osteoporosis PreventionDocument9 pagesNutrition and Osteoporosis PreventionElizabeth DesiNo ratings yet

- 0059 The Osteoporosis RXDocument8 pages0059 The Osteoporosis RXJason YunNo ratings yet

- Clinical Review: OsteoarthritisDocument4 pagesClinical Review: OsteoarthritismarindadaNo ratings yet

- Menopause Di Puskesmas Stabat Kabupaten Langkat: Analisis Faktor Yang Memengaruhi Osteoporosis Pada IbuDocument13 pagesMenopause Di Puskesmas Stabat Kabupaten Langkat: Analisis Faktor Yang Memengaruhi Osteoporosis Pada IbuRun CapNo ratings yet

- ARTIGO OsteoporoseDocument25 pagesARTIGO OsteoporoseIndiara Lorena Barros Ribeiro Da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Group 5 OsteoporosisDocument17 pagesGroup 5 OsteoporosisFranchezka BeltranNo ratings yet

- Primary Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal WomenDocument5 pagesPrimary Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal WomenAzmi FarhadiNo ratings yet

- Osteoarthritis in Women Effects of Estrogen, Obesity and Physical ActivityvDocument15 pagesOsteoarthritis in Women Effects of Estrogen, Obesity and Physical ActivityvKanliajie Kresna KastiantoNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis - 2022 CanvasDocument61 pagesOsteoporosis - 2022 CanvasSHEILA HADIDNo ratings yet

- Mpu3313 - v2 Mohamad Shafik Bin Supaat 821022145381001Document12 pagesMpu3313 - v2 Mohamad Shafik Bin Supaat 821022145381001محمد شافق ابنو شافعتNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Programme On Knowledge Regarding Osteoporosis and Its Management Among Menopausal WomenDocument12 pagesEffectiveness of Structured Teaching Programme On Knowledge Regarding Osteoporosis and Its Management Among Menopausal WomenEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Public Health Nut8Document17 pagesPublic Health Nut8Fiki FerindraNo ratings yet

- Epid 1Document4 pagesEpid 1Annafiatu zakiahNo ratings yet

- AndrologyDocument298 pagesAndrologyPrakash JanakiramanNo ratings yet

- OsteoporosisDocument10 pagesOsteoporosisSandra Arely Rodriguez EscobarNo ratings yet

- Dental Radiography Associated With Term Low Birth Weight: RD 2.1 Radiasi Pada KehamilanDocument4 pagesDental Radiography Associated With Term Low Birth Weight: RD 2.1 Radiasi Pada KehamilanAnastasia PinkyNo ratings yet

- OsteopeniaDocument9 pagesOsteopeniaMohamed EssallaaNo ratings yet

- Conclusion Motor ControlDocument1 pageConclusion Motor ControlmegatNo ratings yet

- Background AthletesDocument1 pageBackground AthletesmegatNo ratings yet

- Casal2017 PDFDocument11 pagesCasal2017 PDFmegatNo ratings yet

- Informative Speech Template: (Describing Chart(s) And/or Graph(s) )Document2 pagesInformative Speech Template: (Describing Chart(s) And/or Graph(s) )megatNo ratings yet

- Notes Aerobic SystemDocument2 pagesNotes Aerobic SystemmegatNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantage Lactate SystemDocument1 pageAdvantages and Disadvantage Lactate SystemmegatNo ratings yet

- Lactate SystemDocument1 pageLactate SystemmegatNo ratings yet

- Vitamins, Minerals, Antioxidants, Phytonutrients, Functional FoodsDocument32 pagesVitamins, Minerals, Antioxidants, Phytonutrients, Functional Foodssatrijo salokoNo ratings yet

- Radical Longevity - Ann Louise GittlemanDocument444 pagesRadical Longevity - Ann Louise Gittlemandjole100% (3)

- Food and NutritionDocument7 pagesFood and NutritionprashantdhanvijayNo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis PowerpointDocument45 pagesOsteoporosis PowerpointAgustina Anggraeni Purnomo100% (1)

- Primal Hormones Made by Aesthetic Primal 1Document59 pagesPrimal Hormones Made by Aesthetic Primal 1enzopark776No ratings yet

- Drug Study Medcor AguinaldoDocument6 pagesDrug Study Medcor AguinaldoYana PotNo ratings yet

- NCM 105 Prelims NotesDocument24 pagesNCM 105 Prelims NotesJustine FloresNo ratings yet

- Oleh Ilham Syifaur Pembimbing Dr. Rahmad Syuhada, Sp. MDocument20 pagesOleh Ilham Syifaur Pembimbing Dr. Rahmad Syuhada, Sp. MMeta MedianaNo ratings yet

- Images - SupportArticles - PRODUCT PPT New 2018Document48 pagesImages - SupportArticles - PRODUCT PPT New 2018Shailendra Singh ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 Nut 116alDocument6 pagesCase Study 1 Nut 116alapi-249635202No ratings yet

- Centenarian inDocument155 pagesCentenarian inViktória MolnárNo ratings yet

- Covid Protocol DetoxDocument20 pagesCovid Protocol DetoxAlfred Sambulan83% (6)

- Vitamin D FracturesDocument11 pagesVitamin D FracturesHolger LundstromNo ratings yet

- Supplement Reference Guide: 1 Edition 2009Document234 pagesSupplement Reference Guide: 1 Edition 2009domNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Osteoporosis 2: Cli Ord J. RosenDocument13 pagesPathogenesis of Osteoporosis 2: Cli Ord J. RosenRonald TejoprayitnoNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D and CalciumDocument33 pagesVitamin D and CalciumAkhmadRoziNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D and Skin DiseasesDocument32 pagesVitamin D and Skin DiseasesShree ShresthaNo ratings yet

- L37 - FPSC Saharanpur 4 G-36, Parshvnath Plaza, Court Road, SAHARANPUR-247001, Cont. - 9319141888Document13 pagesL37 - FPSC Saharanpur 4 G-36, Parshvnath Plaza, Court Road, SAHARANPUR-247001, Cont. - 9319141888Saurabh SinghNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Nutrition and HealthDocument31 pagesThe Relationship of Nutrition and Healthcoosa liquorsNo ratings yet

- 2015 Evidence Analysis Library Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline For The Management of Hypertension in AdultsDocument31 pages2015 Evidence Analysis Library Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline For The Management of Hypertension in AdultscrackintheshatNo ratings yet

- BalanceOil Plus Premium enDocument4 pagesBalanceOil Plus Premium enTóthné MónikaNo ratings yet

- Water Soluble Vitamins: Vitamins Toxicity/Definition Deficiency/Definition Niacin Vitamin ADocument3 pagesWater Soluble Vitamins: Vitamins Toxicity/Definition Deficiency/Definition Niacin Vitamin ARoshin TejeroNo ratings yet

- Nutrition DietaryDocument35 pagesNutrition DietaryAbdul Quyyum100% (2)

- CV DR Aysha Habib KhanDocument18 pagesCV DR Aysha Habib KhanJumadil MakmurNo ratings yet

- Mcqs Upse 2007 Part 2Document14 pagesMcqs Upse 2007 Part 2Jasmine KumarNo ratings yet

- B2 - Effects of UV-C Treatment and Cold Storage On Ergosterol and Vitamin D2 Contents in Different Parts of White and Brown Mushroom (Agaricus Bisporus)Document6 pagesB2 - Effects of UV-C Treatment and Cold Storage On Ergosterol and Vitamin D2 Contents in Different Parts of White and Brown Mushroom (Agaricus Bisporus)Nadya Mei LindaNo ratings yet

- A Functional Approach Vitamins and MineralsDocument15 pagesA Functional Approach Vitamins and MineralsEunbi J. ChoNo ratings yet

- Orthopedics 5 1085Document8 pagesOrthopedics 5 1085Renata YolandaNo ratings yet

- Calcium and Oral Health: A Review: International Journal of Scientific Research September 2013Document3 pagesCalcium and Oral Health: A Review: International Journal of Scientific Research September 2013Maqbul AlamNo ratings yet

- Chap 18 Musculoskeletal SystemDocument29 pagesChap 18 Musculoskeletal SystemAna Dominique Espia100% (1)