Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nomra. Ra Edvq.: by University of Tasmania Library User On 21 April 2018

Uploaded by

Alec BeattieOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nomra. Ra Edvq.: by University of Tasmania Library User On 21 April 2018

Uploaded by

Alec BeattieCopyright:

Available Formats

86 NOTES AND STUDIES

uniformly observed. Dr. Farrer still has to persuade me that, had the

evangelist wanted to render 'deliver the gospel into the bosom of all

nations' into Greek, he would have written icqpvcroeiv TO evayyeXiov els

•noMra. ra edvq.

Dr. Farrer recognizes that we differ in our approach to the interpreta-

tion of Mark (pp. 78 f.). Alas, I cannot agree with his statement of the

difference. Matthew's use of Mark is not central to my argument, though

I still believe that his treatment of Mark is in line with my interpreta-

tion. If there were no Matthew, I would still want to interpret Mark as I

do and would remain convinced that this interpretation is what Marcan

usage requires.

Here is a major difference between us. A large part of my argument

was philological and Professor Moule has discussed it in philological

terms. Except where Dr. Farrer seems to blur a distinction he refrains

from philology. Yet, for Mark philology is particularly important. He is

not writing literary Koine, but for all that is a careful writer. He is much

more regular than Luke, for example, and, if we neglect the rules of his

usage, we misinterpret him. I would not suggest that the exegesis of

Mark is entirely a matter for philology. Sometimes it can decide be-

tween disputed interpretations, sometimes it can set certain limits

within which the interpretation must be found, and sometimes it is of

little use at all. We cannot, however, ignore it in a passage where the

argument turns largely on linguistic considerations.

From these pages it is clear that neither Professor Moule nor Dr.

Farrer have persuaded me. If I remain firm in my main conclusion,

there are one or two points on which I modify my argument. Professor

Moule has made me think more precisely about the meaning of aradr)-

aeade els fiaprvpiov even if he finds the result of my discussion no

more acceptable.

Further, his modification of my arrangement of the line beginning

oTaOrjoeoBe must be considered. I had taken it with the two preceding

lines only: he attaches it also to what follows. This may be right. The

aradrjaeoBe line differs a little in structure from the two previous ones.

On the other hand, I still think that there is a bigger break in the sense at

Sei npanov. If this is so, my arrangement still holds good.

G. D. KILPATRICK

T H E H U N D R E D AND F I F T Y - T H R E E FISHES

I N J O H N X X I . 11

THE reference to 153 fishes in John xxi. 11 has proved a puzzle to com-

mentators. It is widely believed that there is some symbolic significance

in the number, but no interpretation has won universal acceptance. At

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jts/article-abstract/IX/1/86/1684732

by University of Tasmania Library user

on 21 April 2018

NOTES AND STUDIES 87

least eighteen different interpretations have been offered; no doubt a

thorough investigation would discover many more. It is unnecessary to

describe and discuss every interpretation individually;' many of them do

not fit the context, which suggests some connexion with the evangelistic

mission of the church. The interpretations which have been advanced

fall into three classes.

First, some commentators seek to find 153 entities corresponding to

the number of fishes. Perhaps the most widely known is that based on

Jerome's statement that it was believed by Greek and Latin naturalists

that there were 153 varieties of fish. Unfortunately, it is very doubtful

whether Jerome's statement is 'reliable.2 Another explanation3 is that

the passage echoes 2 Chron. ii. 17 f. (16 f. in the LXX), which refers to

153,600 foreigners in Israel in the time of Solomon. This suggestion is

not very plausible. John speaks of 153, not of 153,000, and it is difficult

to explain the loss of the 600. Nor are the gentiles who were subjected

to forced labour very suitable types of the gentiles to be converted to

the liberty of the gospel.

Second, others have pointed out that the number 153 is the sum of

the numbers from 1 to 17, and that 153 dots can be arranged as an

equilateral triangle with 17 dots on the base line.4 This interpretation,

which is at least as old as Augustine, demands that some significance be

found for 17 as well as for 153. It is possible to suggest reasons why 17,

the sum of 10 and 7, is a significant number, but it is not so easy to see

what relevance it has to this context. There is justice in R. H. Lightfoot's

remark on such theories, which would apply equally well to many other

mathematical explanations, '. . . i t remains to be explained, in a form

which will carry conviction, what bearing this has upon the number of

fishes here taken'.5 There might be more probability in the view that

there is a reference to the 17 nations in Acts ii. 7 ff.6 But it is not certain

1

For lists of interpretations see T. Zahn, Einleitung in das N.T.2 (1900),

pp. 498 f.; M. Goguel, Introduction auN.T., vol. ii (1923), pp. 292 f.; W. Bauer,

Das Johannesevangelium (1925), p. 231; R. Bultmann, Das Evangelium des

Johannes (1952), p. 549-

2

R. M. Grant in Harvard Theological Review, xlii (1949), pp. 273 ff.

3

M. Pole, Synopsis Criticorum Aliorumque Scripturae Sacrae Interpretum et

Commentatorum, vol. iv (1712), col. 1311. Verse 16 in the LXX describes the

foreigners as npo<rqXvTovs.

4

See the diagram in E. C. Hoskyns, The Fourth Gospel (edited F. N. Davey,

1947). P- 553-

5

R. H. Lightfoot, St. John's Gospel (edited C. F. Evans, 1956), p. 343.

6

G. A. van den Bergh van Eysinga in Zeitschrift fur die neutestamentliche

Wissenschaft, xiii (1912), pp. 296 f. Acts ii. 7 ff. may be intended to offer a repre-

sentative list of the nations of the world; see S. Weinstock in Journal of Roman

Studies, xxxviii (1948), pp. 43 ff. But there is, as far as I am aware, no evidence

that the number 17 was itself traditional.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jts/article-abstract/IX/1/86/1684732

by University of Tasmania Library user

on 21 April 2018

88 NOTES AND STUDIES

that these verses give a list of exactly 17 nations. It is also uncertain

whether the fourth evangelist knew Acts, and whether, if he did know it,

he would have thought ii. 7 ff. a sufficiently comprehensive list of the

nations of the world. In any case, it has to be explained why he did not

say that there were 17 varieties of fish, instead of adding the numbers

from 1 to 17.

Third, there are many explanations in terms of words which can be

derived from 153 by the principle of what the Jews called gematria.

Hebrew or Greek words are found whose letters have a numerical value

of 153. Most of these suggestions are particularly open to the objection

that such expressions as 'the age to come',1 and 'the high priest of

Judah', 2 have little or no relevance to the context. Eisler3 believed that

153 is to be interpreted as the sum of 76, which has the numerical value

of Sifjuov, and 77, which has the numerical value of ixOvs- This would,

if stated as simply as this, be open to the objection that Simon is one of

the fishermen, not one of the fish, and that it is tautologous to see in the

number of the fish itself a word for a fish. In fact, Eisler builds up an

elaborate symbolical interpretation of the whole passage which need not

be discussed here but which, it may be confidently stated, is unlikely to

find any more support in the future than it has found in the past.

As none of the above suggestions is entirely satisfactory it is not

superfluous to offer another. It has often been observed that the story

of the fishes in John xxi may be partly dependent on Ezek. xlvii, especially

on verse io. 4 The prophecy tells of the miraculous stream of waters

which will flow from Jerusalem and bring healing and life to the Dead

Sea. There will be many fish, and fishermen will stand from En-gedi to

En-eglaim, which will be a place for the spreading out of nets. If the

number 153 does represent gematria, it is not unreasonable to look for

it in the proper names in this Old Testament passage. ]'J? may not be

significant since it means 'spring' and is not necessarily to be thought

of as an essential part of the proper names. The numerical value of HI

is 17 (X = 3 , "T = 4, "* = 10), and that of D^JS? is 153 (S? = 70, 1 = 3,

\> = 30, ' = 10, D = 40).

It may, therefore, be that John observed the fact that the numerical

values of Gedi and Eglaim were 17 and 153 and that these numbers

were mathematically related. The number of fishes may thus represent

the places in Ezek. xlvii where the fishermen were to stand and spread

their nets. It would, perhaps, have been better if the number 153 could

have been more directly related to the contents of the nets, rather than

1 2

Cited by Bultmann, loc. cit. Cited by Goguel, loc. cit.

3

R. Eisler, Orpheus—the Fisher (1921), pp. noff.

4

This O.T. passage may also be one of those underlying John vii. 38.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jts/article-abstract/IX/1/86/1684732

by University of Tasmania Library user

on 21 April 2018

NOTES AND STUDIES 89

to the place where they were spread, but the latter interpretation, never-

theless, makes sense in the context. Whether the evangelist understood

Ezek. xlvii. 8 to be a reference to Galilee is a question which need not

be discussed here.

This hypothesis is not without difficulties. The other numbers in the

fourth gospel are not, as far as I can see, to be interpreted by gematria.

This does not, however, exclude the possibility that this particular

number is to be interpreted by that principle. Similarly, the fact that in

ix. 7 the evangelist sees significance in the meaning of a Hebrew name

is reconcilable with the view that other names are not to be interpreted

in a comparable way. The evangelist is certainly aware of some signi-

ficance in some numbers. It is, for example, generally admitted that it is

not by chance that there are seven signs and seven sayings beginning

with 'I am'.

Another possible difficulty is that this hypothesis presupposes that

readers of a Greek book could be expected to refer to an O.T. passage

in Hebrew which is not explicitly cited, and to recognize in it an example

of gematria. This difficulty is eased, if not removed, if it is believed that

Rev. xiii. 18 presupposes a knowledge of the numerical value of Hebrew

letters. John ix. 7 shows that the evangelist was aware of the possible

significance of a Semitic name, though, admittedly, the meaning there

is given in Greek.

Finally, there is the difficulty that this hypothesis is too speculative

to be certain. This may be conceded; the hypothesis is advanced tenta-

tively and with a sense of its uncertainty. But if it be granted that some

explanation of the number 153 is needed, the suggestion here offered

may seem more plausible than many which have been offered. There is,

at the very least, an interesting coincidence. J. A. EMERTON

T R I N I T A R I A N T H E O L O G Y AND T H E ECONOMY1

ONE of the perplexing episodes in the history of Christian doctrine is

that of the fate of Tertullian's trinitarian theology, cast in 'economic'

terms. Broadly speaking, two views of this have been held: Harnack and

Loofs have bracketed it together with fourth-century trinitarian theo-

logies like that of Marcellus of Ancyra under the label okonomisch-

trinitarische Anschauungen; these later trinitarian theories treated the

procession of the persons from the godhead in historical terms: both

the Son and the Holy Spirit found their place alongside the Father in

1

I have to thank Mr. C. H. Roberts, Secretary to the Delegates, The Claren-

don Press, Oxford, and Professor G. W. H. Lampe, for allowing me to consult

material in the files of the forthcoming Lexicon of Patristic Greek.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jts/article-abstract/IX/1/86/1684732

by University of Tasmania Library user

on 21 April 2018

You might also like

- Books by Gauranga Darshan Das-1Document48 pagesBooks by Gauranga Darshan Das-1Anant Kumar50% (2)

- Campione! 1 - Heretic GodDocument263 pagesCampione! 1 - Heretic GodRaffy Gomez100% (5)

- I'm Not A Boy PrevinDocument5 pagesI'm Not A Boy PrevinAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Beasts at Ephesus (A. J. Malherbe)Document11 pagesBeasts at Ephesus (A. J. Malherbe)sabioNo ratings yet

- Weidemann Wheel Loader 3002 DP Spare Part ListDocument22 pagesWeidemann Wheel Loader 3002 DP Spare Part Listsandrapeters110902bak100% (125)

- Reckford, Studies in PersiusDocument30 pagesReckford, Studies in Persiusoliverio_No ratings yet

- Hebrews WestcottDocument585 pagesHebrews WestcottLeonardo MendietaNo ratings yet

- A Study in The First GospelDocument17 pagesA Study in The First GospelCarmelo B. CulveraNo ratings yet

- Bright. St. Augustine 'De Spiritu Et Littera'. 1914.Document106 pagesBright. St. Augustine 'De Spiritu Et Littera'. 1914.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Honeyman 1949 - Two Contributions To Canaanite ToponymyDocument4 pagesHoneyman 1949 - Two Contributions To Canaanite ToponymyJoshua AlfaroNo ratings yet

- The Wanderer" and "The SeafarerDocument11 pagesThe Wanderer" and "The SeafarerNorthman57No ratings yet

- Levitical Priests Criticism of The PentateuchDocument312 pagesLevitical Priests Criticism of The PentateuchDavid BaileyNo ratings yet

- George Melville Bolling Analyzes Homeric and Vergilian TextsDocument4 pagesGeorge Melville Bolling Analyzes Homeric and Vergilian TextsPietro VerzinaNo ratings yet

- Baines. Interpreting The Story of The Shipwrecked Sailor.Document19 pagesBaines. Interpreting The Story of The Shipwrecked Sailor.Belén CastroNo ratings yet

- Two Centuries of Pentateuchal Scholarship - Joseph BlenkinsoppDocument31 pagesTwo Centuries of Pentateuchal Scholarship - Joseph BlenkinsoppGarrett JohnsonNo ratings yet

- The Ptolemy and The HareDocument10 pagesThe Ptolemy and The HareJoshua GonsherNo ratings yet

- Bart D. Ehrman (1993) - Heracleon, Origen, and The Text of The Fourth Gospel. Vigiliae Christianae 47.2, Pp. 105-118Document15 pagesBart D. Ehrman (1993) - Heracleon, Origen, and The Text of The Fourth Gospel. Vigiliae Christianae 47.2, Pp. 105-118Olestar 2023-08-04No ratings yet

- Delphi and The Homeric H Ymn To A PolloDocument18 pagesDelphi and The Homeric H Ymn To A PolloHenriqueNo ratings yet

- A Survey of Greek DefixionesDocument47 pagesA Survey of Greek DefixionesMrBond666No ratings yet

- HeSogdian GodDocument14 pagesHeSogdian GodBatsuren BarangasNo ratings yet

- Und Seine Stelle in Der ReligionsgeschichteDocument17 pagesUnd Seine Stelle in Der ReligionsgeschichteYehuda GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Was There A Nominative Gerund (Iterum de Gerundio Et Gerundivo) - Hahn 1965Document28 pagesWas There A Nominative Gerund (Iterum de Gerundio Et Gerundivo) - Hahn 1965Konstantin PredachenkoNo ratings yet

- New Testament StudiesDocument17 pagesNew Testament Studiesjavier andres gonzalez cortesNo ratings yet

- Philippians 3:7-11Document15 pagesPhilippians 3:7-11Steven E. A. HernandezNo ratings yet

- How Fulgentius Interpreted Apollo's HorsesDocument17 pagesHow Fulgentius Interpreted Apollo's HorsesluliexperimentNo ratings yet

- The LotsDocument93 pagesThe LotsJean Henrique Costa100% (1)

- Why 1 John 5 7 8 is in the BibleDocument13 pagesWhy 1 John 5 7 8 is in the BibleAl DobkoNo ratings yet

- Dios No Esta Muerto (A)Document6 pagesDios No Esta Muerto (A)Andres CubilloNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Terapi WicaraDocument6 pagesJurnal Terapi WicaraPandu SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Studies in Hebrew Roots and Their EtymologyDocument6 pagesStudies in Hebrew Roots and Their Etymologykiki33No ratings yet

- Classical Association of Canada: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument12 pagesClassical Association of Canada: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPmasanta11No ratings yet

- Biblical Greek and post-biblical Hebrew in the minor Greek versions. On the verb συνϵτ �ζω "to render intelligent" in a scholion on Gen 3:5, 7Document11 pagesBiblical Greek and post-biblical Hebrew in the minor Greek versions. On the verb συνϵτ �ζω "to render intelligent" in a scholion on Gen 3:5, 7Gamal NabilNo ratings yet

- A Grammar of The Vulgate (BW New OCR and Margin Cropped - 19 Jan 2017 For All PDFDocument175 pagesA Grammar of The Vulgate (BW New OCR and Margin Cropped - 19 Jan 2017 For All PDFVarga BennóNo ratings yet

- The Lucan Christ and Jerusalem - τελειοῦμαι (Lk 13,32) - J Duncan M. DerretDocument8 pagesThe Lucan Christ and Jerusalem - τελειοῦμαι (Lk 13,32) - J Duncan M. DerretDolores MonteroNo ratings yet

- Numenius and Alcinous On The First Principle John WhittakerDocument11 pagesNumenius and Alcinous On The First Principle John WhittakerClassicusNo ratings yet

- Ta Hagia Na Epístola de HebreusDocument12 pagesTa Hagia Na Epístola de HebreusjtpadilhaNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Use of "HagiaDocument12 pagesUnderstanding the Use of "Hagiahugo rubenNo ratings yet

- Philo L261 PDFDocument595 pagesPhilo L261 PDFΒασίλειος ΣωτήραςNo ratings yet

- HermippusDocument7 pagesHermippusEduardo Gutiérrez GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Zeno Clean The Spears OnDocument368 pagesZeno Clean The Spears OnumitNo ratings yet

- Philo, Volume IVDocument10 pagesPhilo, Volume IVgolemgolemgolemNo ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument30 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldPreetidevNo ratings yet

- QumramDocument7 pagesQumramtecnico.carlosaguilarpNo ratings yet

- Short Study: Jack CollinsDocument8 pagesShort Study: Jack CollinsRazia MushtaqNo ratings yet

- The Authorship of the Peshitta: Were Its Translators Jewish, Christian, or BothDocument9 pagesThe Authorship of the Peshitta: Were Its Translators Jewish, Christian, or Bothivory2011No ratings yet

- American PhylologyDocument29 pagesAmerican PhylologyMishel TinitanaNo ratings yet

- Once Again On Eusebius On Aristocles On Timon On PyrrhoDocument22 pagesOnce Again On Eusebius On Aristocles On Timon On PyrrhoGustavo Adolfo OspinaNo ratings yet

- The Magnificat: Cento, Psalm or ImitatioDocument22 pagesThe Magnificat: Cento, Psalm or ImitatioJavi FNo ratings yet

- Vlastos G. - Theology and Philosophy in Early Greek ThoughtDocument28 pagesVlastos G. - Theology and Philosophy in Early Greek Thoughthowcaniknowit100% (3)

- Luraghi - 2002 - Helots Called Messenians A Note On Thuc 11012Document5 pagesLuraghi - 2002 - Helots Called Messenians A Note On Thuc 11012Anonymous Jj8TqcVDTyNo ratings yet

- 89306-Article Text-237951-2-10-20220713-1Document5 pages89306-Article Text-237951-2-10-20220713-1Rodney AstNo ratings yet

- Taran - The First Fragment of Heraclitus PDFDocument16 pagesTaran - The First Fragment of Heraclitus PDFMicheleCondòNo ratings yet

- (Joshua Katz, Gods and VowelsDocument32 pages(Joshua Katz, Gods and VowelsLucy Velasco OropezaNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Ritual of Opening The MouthDocument15 pagesNotes On The Ritual of Opening The MouthPatrick Andrew McCoyNo ratings yet

- Explore Society's Ancient Egyptian StelaDocument8 pagesExplore Society's Ancient Egyptian StelaImhotep72No ratings yet

- D. W. Thomas VT 10 (1960), Kelebh 'Dog' Its Origin and Some Usages of It in The Old TestamentDocument19 pagesD. W. Thomas VT 10 (1960), Kelebh 'Dog' Its Origin and Some Usages of It in The Old TestamentKeung Jae LeeNo ratings yet

- Second Millenium Antecedents To The Hebrew ObDocument18 pagesSecond Millenium Antecedents To The Hebrew Obevelinflorin100% (1)

- Whittaker - A Hellenistic Context For John 10.29Document20 pagesWhittaker - A Hellenistic Context For John 10.29Kellen PlaxcoNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Spinozas LatinityDocument37 pagesAspects of Spinozas LatinityannboukouNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Society of America Language: This Content Downloaded From 140.206.154.236 On Sun, 02 Apr 2017 05:08:33 UTCDocument6 pagesLinguistic Society of America Language: This Content Downloaded From 140.206.154.236 On Sun, 02 Apr 2017 05:08:33 UTCyumingruiNo ratings yet

- The Semantics of A Political ConceptDocument29 pagesThe Semantics of A Political Conceptgarabato777No ratings yet

- CBS Annual Conference Abstracts 2021Document7 pagesCBS Annual Conference Abstracts 2021Alec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Tasmanian Road Rules Handbook Version 2 2021Document82 pagesTasmanian Road Rules Handbook Version 2 2021Alec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Tasmanian Road Rules HandbookDocument82 pagesTasmanian Road Rules HandbookandyhilbertNo ratings yet

- Nomra. Ra Edvq.: by University of Tasmania Library User On 21 April 2018Document4 pagesNomra. Ra Edvq.: by University of Tasmania Library User On 21 April 2018Alec BeattieNo ratings yet

- 39087009930571score PDFDocument286 pages39087009930571score PDFdenieren 3421No ratings yet

- Trombone Lipping ArticleDocument12 pagesTrombone Lipping ArticleAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Another Look at Mature Creation: P.G. NelsonDocument7 pagesAnother Look at Mature Creation: P.G. NelsonAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Seed Industry Plan: Tasmanian Crop and PastureDocument8 pagesSeed Industry Plan: Tasmanian Crop and PastureAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Flathead Abundance Population Oct 2014 PDFDocument44 pagesFlathead Abundance Population Oct 2014 PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Impact of Gillnet Fishing On Inshore Temperate Reef Species PDFDocument138 pagesImpact of Gillnet Fishing On Inshore Temperate Reef Species PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Flathead Abundance Population Oct 2014 PDFDocument44 pagesFlathead Abundance Population Oct 2014 PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Impact of Gillnet Fishing On Inshore Temperate Reef Species PDFDocument138 pagesImpact of Gillnet Fishing On Inshore Temperate Reef Species PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Stump, Eleonore, Atonement, The Anselmnian Interpretation of Atonement 71-112, Oxford Scholarship Online, Sept. 2018Document65 pagesStump, Eleonore, Atonement, The Anselmnian Interpretation of Atonement 71-112, Oxford Scholarship Online, Sept. 2018Alec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Tasmania's Plan to Grow a $10 Billion Agri-Food Sector by 2050Document12 pagesTasmania's Plan to Grow a $10 Billion Agri-Food Sector by 2050Alec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Impact of Gillnet Fishing On Inshore Temperate Reef Species PDFDocument138 pagesImpact of Gillnet Fishing On Inshore Temperate Reef Species PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Hebrew For WievDocument85 pagesHebrew For WievGoran Jovanović80% (5)

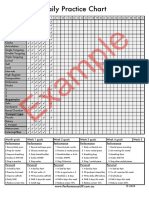

- Daily Practice Chart Portrait Sheet1 PDFDocument2 pagesDaily Practice Chart Portrait Sheet1 PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Tasmanian Road Rules HandbookDocument82 pagesTasmanian Road Rules HandbookandyhilbertNo ratings yet

- A 14 SZ Motet Tenorja - Clark PHDDocument317 pagesA 14 SZ Motet Tenorja - Clark PHDCsaba KissNo ratings yet

- Daily Practice Chart Portrait Sheet1 PDFDocument2 pagesDaily Practice Chart Portrait Sheet1 PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Girg, Walter - 0005 PDFDocument18 pagesGirg, Walter - 0005 PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Girg, Walter - 0005 PDFDocument18 pagesGirg, Walter - 0005 PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Pub Trumpet-Technique PDFDocument199 pagesPub Trumpet-Technique PDFRicardo de AragãoNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 Theory 2017 ExamDocument18 pagesGrade 5 Theory 2017 ExamAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Heiser Psa82inJohn10 RegSBL2011Document14 pagesHeiser Psa82inJohn10 RegSBL2011Alec Beattie100% (1)

- Operation of The Australian Defence Force's Resistance To Interrogation TrainingDocument30 pagesOperation of The Australian Defence Force's Resistance To Interrogation TrainingAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Dilley and Tafa Cory Damned Final Print VersionDocument35 pagesDilley and Tafa Cory Damned Final Print VersionAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Zygo PDFDocument10 pagesZygo PDFAlec BeattieNo ratings yet

- Church History 79:1 (March 2010), 1 –39. Mission from Below: Captive Women and Conversion on the East Roman FrontiersDocument39 pagesChurch History 79:1 (March 2010), 1 –39. Mission from Below: Captive Women and Conversion on the East Roman FrontiersEm RNo ratings yet

- Three Main Types of SermonsDocument4 pagesThree Main Types of SermonsShiela Losloso0% (1)

- Jadal Al Madhhab 17 10 2023Document407 pagesJadal Al Madhhab 17 10 2023MaxNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Ecumenical MovementDocument5 pagesMeaning of Ecumenical MovementAjo Alex100% (1)

- Federal Guidance on Religious Liberty ProtectionsDocument25 pagesFederal Guidance on Religious Liberty ProtectionsDrew ReadyNo ratings yet

- The Birth of The MessiahDocument55 pagesThe Birth of The MessiahMika NainggolanNo ratings yet

- Sixth and Seventh Books of MosesDocument70 pagesSixth and Seventh Books of MosesEmmanuella Obi Ogochukwu100% (12)

- Chess Results ListDocument18 pagesChess Results Listmananthadhani898No ratings yet

- Three Signata: Anicca, Dukkha, AnattaDocument17 pagesThree Signata: Anicca, Dukkha, AnattaBuddhist Publication Society100% (1)

- Cruzada Church Guest Music Teams Schedule and ConfirmationsDocument6 pagesCruzada Church Guest Music Teams Schedule and ConfirmationsPaolo Roel Ulangca RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Ethical Principle of BuddhismDocument3 pagesLesson 1 Ethical Principle of BuddhismRandom TvNo ratings yet

- UD Y Purpo SE S: ONE ONEDocument52 pagesUD Y Purpo SE S: ONE ONEJoanne ManacmulNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Jainism On Early Kannada Literature Sheldon Pollock'S Work Language of GodsDocument24 pagesThe Influence of Jainism On Early Kannada Literature Sheldon Pollock'S Work Language of GodsRajender BishtNo ratings yet

- Weekly Activities and Needs of the Church Diocese of NsuKKaDocument2 pagesWeekly Activities and Needs of the Church Diocese of NsuKKaCHIAMAKA NWAGUNo ratings yet

- The Book of Revelation: From God's Word The Holy Bible, KJVDocument41 pagesThe Book of Revelation: From God's Word The Holy Bible, KJVSohrabNo ratings yet

- Chakras JoSDocument2 pagesChakras JoSWalter EichnerNo ratings yet

- Vdocument - in The Necronomicon Ritual Book by Kuriakos Magicthe This Necronomicon RitualDocument54 pagesVdocument - in The Necronomicon Ritual Book by Kuriakos Magicthe This Necronomicon RitualAnthonyNo ratings yet

- Jesus Prays for Our Protection and UnityDocument6 pagesJesus Prays for Our Protection and UnityMax MbiseNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Veena DasDocument13 pagesEthics, Veena DasPatrice SchuchNo ratings yet

- Part-23-Event-13-Describe A Festival or National Holiday in Your CountryDocument9 pagesPart-23-Event-13-Describe A Festival or National Holiday in Your CountryAnhĐăngNo ratings yet

- 0125 Conversion of ST PaulDocument4 pages0125 Conversion of ST PaulVincent InsingaNo ratings yet

- Altar ServersDocument4 pagesAltar ServersWellsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Through The Eyes of TravelersDocument11 pagesChapter 5 Through The Eyes of TravelersShivie VashishthaNo ratings yet

- James Chapter 1 Bible StudyDocument4 pagesJames Chapter 1 Bible StudyPastor Jeanne100% (1)

- Star-Gazing In: CologneDocument16 pagesStar-Gazing In: Colognejyjc_admNo ratings yet

- الحسبة في السنة النبوية،Document30 pagesالحسبة في السنة النبوية،ZAMM ZammNo ratings yet

- 1080 - Esau - Edom, and The Trail of The Serpent - IIDocument15 pages1080 - Esau - Edom, and The Trail of The Serpent - IIAgada PeterNo ratings yet

- Substance of Amulets and Cultural DutyDocument17 pagesSubstance of Amulets and Cultural DutyGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet