Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Administrative Professionals and The Diffusion of Innovations: The Case of Citizen Service Centres

Uploaded by

AmandaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Administrative Professionals and The Diffusion of Innovations: The Case of Citizen Service Centres

Uploaded by

AmandaCopyright:

Available Formats

doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01882.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND THE

DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS: THE CASE OF CITIZEN

SERVICE CENTRES

YOSEF BHATTI, ASMUS L. OLSEN AND LENE HOLM PEDERSEN

This article examines how administrative professionals affect the diffusion of one-stop shops in

the form of integrated citizen service centres (CSC) in a Danish local government setting. CSCs

are an example of a new organizational form: functionally integrated small units (FISUs). The

diffusion of the CSCs among municipalities is used to analyse how administrative professionals

act as drivers in the process of organizational level innovation. Furthermore, it is examined how

institutional, political and economic characteristics of municipalities influence the likelihood of

adoption. The findings highlight that a high concentration of administrative professionals indeed

make the adoption of CSCs more likely. Additionally, the findings confirm three commonly stated

hypotheses from the diffusion of innovations literature, namely that need based demands, wealth

and the regional supply of CSC increase the likelihood of its adoption.

INTRODUCTION

What determines the diffusion of organizational level innovations across jurisdictions? In

the early diffusion literature, highly skilled and professional staff were hypothesized to

be positively associated with the motivation and ability to innovate (Mohr 1969; Walker

1969; Rogers 2003). Walker (1969, p. 883), for instance, pointed to professional staff as one

of many ‘slack resources’, which provide organizations with the luxury of experimenting

with the adoption of new programmes or policies. Recently, a growing empirical body

of diffusion literature has pointed to the facilitating role of legislative and administrative

professionals due to their skills (Mintrom 1997; Sapat 2004; Shipan and Volden 2006),

incentives (Teodoro 2008, 2009), norms (Moon and deLeon 2001; Yang 2007) and networks

(Mintrom 1997, Mizruchi and Fein 1999; Balla 2001).

The present paper adds to this newer literature on professionals in the diffusion

processes as it investigates the effect of administrative professionals on the likelihood

of adopting a new organizational form in a local government context. This is done by

studying the diffusion of citizen service centres (CSCs) in Danish municipalities 1987–2005.

CSCs can be seen as a reflection of an alternative, theoretical organizational form – the

functionally integrated small units (FISU) model – which has been described as a solution

to problems of functional fragmentation (Fountain 1994; Seidle 1995; Bent et al. 1999).

The contribution of the article is twofold: First, it examines the role of administrative

professionals in the diffusion of the new organizational form. By focusing on this distinct

subset of public employees, we are able to highlight how the skills, incentives and

shared norms of a particular professional group may bring about organizational level

innovations in a local government setting. As it will turn out, administrative professionals

have a robust impact on the spread of CSCs in Danish municipalities. Second, it adds

to the general diffusion literature that empirically tests the determinants of adoption of

innovation, in this case in the field of municipalities (Knoke 1982; Tolbert and Zucker

1983; Gregersen 2000; Moon and deLeon 2001; Dahl and Hansen 2006). By including

Yosef Bhatti and Asmus L. Olsen are in the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen. Lene Holm

Pedersen is in the Danish Institute of Govermental Research, Copenhagen.

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ,

UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

578 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

variables commonly discussed in the existing literature, we provide a new venue for

testing the generality of previous findings. The analysis confirms the importance of

regional emulation (Walker 1969; Gray 1973; Berry and Berry 1990; Shipan and Volden

2006), economic wealth (Walker 1969; Pallesen 2004) as well as need driven demands

(Walker 1969; Sapat 2004) for organizational level innovation.

It should be emphasized that by innovation, we refer to Walker’s (1969) definition,

which states that an innovation is to be understood as a policy, programme or idea

which is new to the organization adopting it. Thereby, the focus is when an organization

does something new – not whether this innovation is new or merely imitative from a

field level perspective. Hence, by the term ‘innovation’ we refer to organizational level

innovation. This is in line with most of the existing diffusion literature (Rowe and Boise

1974, p. 285; Berry and Berry 1999). In the section that follows, the case of CSCs in

Danish municipalities is presented. Next, the administrative professionals hypothesis and

alternative hypotheses are presented with departure in the existing literature. Then the

estimation method and the measures are discussed before the analysis of diffusion is

carried out. Finally, the results are discussed and put into perspective.

THE DANISH PUBLIC SECTOR AND CSCs AS A NEW ORGANIZATIONAL FORM

The empirical field of investigation is Danish municipalities. Though formally a unitary

state, Denmark is an interesting case for diffusion studies as the municipal level enjoys a

high degree of autonomy (like for instance the state level in the US which is the context for

a large part of the diffusion literature). First, fiscal decentralization to the municipal level

is considerable, including the right of taxation and expenditures amounting to around 50

per cent of overall public spending. Second, the municipalities have relative discretion in

service provision and the organization of the administrative and political level. Hence, the

possibility of decentralized institutional or policy experimentation which has motivated

diffusion studies in mostly federal systems (Shipan and Volden 2006), also apply to the

context of Denmark.

During the period under investigation (1987–2005), the Danish public sector was

organized on three levels. The highest level was the state, where overall national policy

strategy was established and where some general services such as the police and army

were organized. On the next level, the 16 regions were mainly responsible for hospitals,

the environment and some specialized social services. The remaining, and thus the vast

majority, of public services were carried out at the lowest administrative level, namely the

municipality. The municipal sector consisted of 271 entities with an average population

of slightly less than 20,000. The average size of a municipality was about 159 square

kilometres and the average budget slightly more than 10,000 US dollars per inhabitant

per year (Ministry of Interior and Health 2008).

The idea of CSCs was introduced at the municipal level in 1987 and spread to other local

entities. Hence, the introduction of CSCs occurred voluntarily without any formal pressure

from the government. Local Government Denmark (the interest group and member

authority of Danish municipalities) promoted experiences from the municipalities that

adopted the idea but did not exert any pressure on its members to adopt it. Hence, the idea

of CSCs was available to municipalities at an early stage but whether they chose to adopt

it was entirely voluntary. The maps in figure 1 show the spread of the organizational

form in Denmark since CSCs were presented in the municipal arena for the first time

in 1987 (Laursen 2006). Over the course of 18 years, the organizational form has spread

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 579

FIGURE 1 The prevalence of CSCs in Danish municipalities in 1987, 1993, 1998 and 2005, respectively

widely throughout the country such that slightly less than 50 per cent of municipalities

had adopted it by 2005.

The idea behind CSCs can be described as providing citizens with one entrance point

where they can access a variety of public services. The CSCs aim to provide services

for the citizen on the spot, and they are often organized in a way where the aim is that

one person can serve all customers. Furthermore, they have a unified leadership at the

production level and the case-work is mostly completed in the CSCs rather than being

passed on to other administrative units (Pedersen 2009). The services carried out in a CSC

can include the handling of forms, replacement of passports and driving licences and so

on (Local Government Denmark 2006).

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

580 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

Among one-stop shops one can differentiate between: (1) information counters, which

guides the citizen to the relevant services; (2) convenience stores, where many different

transactional services are located in a single office or on one web site; and (3) true one-stop

shops, which integrates concerns of specific client groups or specific events, and the

services are integrated rather than just co-located (Kubicek and Hagen 2001). The Danish

CSCs can be characterized as true one-stop shops, and may also be seen as examples

of functionally integrated small units (FISUs), as they attempt to integrate the citizen-

oriented services in the municipalities. The FISU model is an alternative organizational

form that was firstly described in the 1960s. It envisions small, but complete production or

service units, and is thus characterized by social compactness, unified supervision at the

intended production level, merged production functions and output closure. The synergy

of these factors is seen as making this form of organization distinct from other attempts

to increase cooperation and coordination (Rainey 1990). The downside of this type of

organization could be that the focus on comprehensive administration comes at the costs

of specialization.

Thus, the present study is an analysis of the factors driving the diffusion of this new

organizational form, which is hoped to solve the problems of an increasingly fragmented

public sector.

RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

Following Walker’s definition (1969, p. 881), an innovation may simply be defined as a

policy, programme or idea which is new to a political entity. The process by which an

innovation spreads in a social system is denoted as ‘diffusion’ (Rogers 2003). The literature

has isolated a number of economic, political and institutional correlates of diffusion, that

is, factors that promote or inhibit the spread of innovations among jurisdictions (see, for

example, Mohr 1969; Walker 1969; Gray 1973; Berry and Berry 1990; Sapat 2004). Since no

unified theory has emerged for studying the correlates of innovation, looser frameworks

which combine both internal (economical, societal or political) factors and external factors

(emulation, learning and competition among jurisdictions within a social system) have

gained dominance in the literature (Walker 1969; Berry and Berry 1999).

In line with the majority of modern empirical diffusion studies, we employ an explo-

rative approach to the adoption of innovations with hypotheses derived from theoretical

extensions of existing contributions, including both internal and external factors, rather

than from grand theory (Berry and Berry 1999). First, we develop the argument underlying

our central hypothesis concerning the influence of administrative professionals on the

likelihood of adoption. Second, we discuss and propose five general alternative hypothe-

ses for the most prevalent factors in the existing literature. The inclusion of the alternative

hypotheses allows us to test the most debated causes of adoption in yet another venue as

well as it allows us to achieve an appropriate specified model.

Administrative professionals and the diffusion of innovations

Part of the literature on the diffusion of innovations has recently turned to the facilitating

or constraining role of professional skills, incentives norms and networks in the diffusion

process (see, for example, Balla 2001; Moon and deLeon 2001; Sapat 2004; Shipan and

Volden 2006; Teodoro 2009). We consider a particular interesting group of actors, namely

administrative professionals. Administrative professionals are public employees with a

university degree in economics, political or other social sciences, which have increasingly

gained importance in the municipal labour market (Bhatti et al. 2009).

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 581

The literature is far from unified in its view on professions (compare, for instance,

Roberts and Dietrich 1999 and Teodoro 2009). In the present study we emphasize the

importance of occupation as well as degrees of theoretical and analytical skills (see

also Andersen and Pedersen 2010). Among people occupied with teaching, for instance,

university teachers are seen as having a higher level of professionalism than school

teachers, who again hold a higher level of professionalism than pre-school teachers.

This is due to the fact that the university teachers possess more theoretical knowledge

and more training in analytical skills, even if university teachers may have different

areas of specialization and different intra-occupational norms. Similarly, in the health

sector physicians have a higher level of professionalism than nurses, who again hold

a higher level of professionalism than health assistants. One can argue that physicians

have different specializations (for example, surgery vs. medicine); nevertheless they hold

the same overall occupation and their level of professionalism is seen as higher as

they have more theoretical knowledge than for instance nurses or health assistants. In

administration – the area at scrutiny here – university trained administrators are seen as

more professionalized than administrators with a vocational training, which traditionally

has been the occupation employed in the Danish municipalities. They have high level

of analytical knowledge and share the same occupation (see, for example, Dahler-Larsen

and Ejersbo 2003), namely administration.

It should be noted that the administrative professionals in this study do only partly

qualify as professionals in the sense of the sociology of professions (Roberts and Dietrich

1999; Andersen 2005, p. 25). Here professions are not only defined as belonging to

an occupation with a certain level of theoretical knowledge but also with firm intra-

occupational norms. While the administrative professionals in this study have similar

occupations and hold significant theoretical knowledge, their norms may differ since

they have different educational backgrounds. However, this is essentially a question that

should be subject to a more through empirical analysis.

Drawing on the existing literature on administrative professionals (Balla 2001; Moon

and deLeon 2001; Sapat 2004; Shipan and Volden 2006; Teodoro 2009) we argue that

this group is particularly likely to act as facilitators of innovations for two main supple-

mentary reasons: Their analytical skills and theoretical knowledge, and their incentives.

Furthermore, we briefly discuss the theoretical possibility that shared professional norms

and professional networks could work as a causal operator for adoption.

First, in order for a municipality to bring about the adoption of an innovation, certain

skills and knowledge are needed. We argue that administrative professionals, due to

their university degree, have relatively strong theoretical knowledge and analytical skills

which are important for the adoption of organizational innovations, including CSC.

As innovations are characterized by being some sort of disjuncture from the standing

operation procedures and routines within an organization (Roberts 1992, p. 57), the ability

to persuade relevant actors, motivate subordinates and build coalitions becomes crucial

(Teske and Schneider 1994). Furthermore, as any other disjuncture does, the adoption

of innovations encompasses uncertainty and a need for risk-taking. Hence, necessary

information and ability to reduce that uncertainty and promote risk-taking should

facilitate the adoption of innovations (Rogers 2003). Walker (1969) pointed to the skills of

professional staff as one of many ‘slack resources’, which provides organizations with the

luxury of experimenting with the adoption of new programmes or policies. In line with

this, Sapat (2004) finds that the ‘ability and capacity of institutional actors’ positively affects

the adoption of environmental innovations to administrative agencies. The importance of

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

582 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

knowledge and ability to define and solve problems as means for adopting innovations is

also well known in the policy entrepreneur literature (Roberts 1992; Teske and Schneider

1994; Mintrom 1997). Hence, also within this perspective, administrative professionals act

as facilitators of innovation as they serve as bureaucratic entrepreneurs (Roberts 1992).

Second, administrative professionals have the necessary incentives to seek and success-

fully adopt innovations. Following Teske and Schneider’s (1994, p. 338) description of city

managers’ entrepreneurial incentives, we argue that administrative professionals enhance

their professional reputation and career possibilities through the successful adoption of

professionally approved innovations. That is, administrative professionals are largely

recruited to take up an entrepreneurial role (Munck 2003) and thus their performance is

widely evaluated on their ability to carry out innovations. Teodoro (2008, 2009) found evi-

dence that diagonally recruited professional bureaucrats (that is, from outside of the orga-

nization) are potential suppliers of policy innovation, as they indeed are evaluated on their

reputation for supplying organizational innovation. Thus, administrative professionals

may have strong incentives to signal their credentials through the adoption of innovations.

Finally, we briefly review the possibility of shared norms and professional networks

among administrative professionals as an alternative explanation for the adoption of

innovations. As Brehm and Gates (1997) have suggested, professional socialization moti-

vates administrators to pursue their professions’ favoured policies. If administrative

professionals could be considered a unified profession; they could bring about a diffusion

of innovations from their professional communities to the municipal organizational field

(Balla 2001; Yang 2007). Furthermore, diffusion as a mechanism of shared professional

norms and networks would equally capture the notion of normative isomorphism as pro-

posed by Dimaggio and Powell (1983). Some studies have indeed attempted to capture

such an effect through both organization membership of formal professional networks

(see, for example, Balla 2001; Yang 2007) as well as the manager’s educational background

(see, for example, Budros 2004). Professionalism in terms of networks has been studied

by Balla (2001), who examines the link between professional networks and health policy

diffusion. Rabe (1999) has found that entrepreneurial administrators borrow innovations

from ‘policy communities’ related to their professions. A similar idea has also been

touched on by Walker (1969, p. 895) who refers to ‘occupational contact networks’, which

spreads knowledge of innovations among jurisdictions. However, as we have noted in

the beginning of the chapter, the object of our study is not a unified profession with firm

intra-occupational norms (Roberts and Dietrich 1999; Andersen 2005, p. 25). Accordingly,

suspect that shared norms and professional network are of less importance when explain-

ing the role of administrative professionals in the adoption of innovations. In sum, with

reference to their level of analytical skills theoretical knowledge and incentives adminis-

trative professionals can be hypothesized as facilitators of the adoption of innovations,

including that of CSC.

Hypothesis 1: The greater the concentration of administrative professionals, the higher

the likelihood of adoption.

Alternative hypotheses

In the following discussion we propose five alternative hypotheses for the adoption

of CSC – for specifically regional emulation (Walker 1969; Gray 1973; Berry and Berry

1990; Shipan and Volden 2006), organizational wealth and size (Mohr 1969; Walker

1969; Moon and Norris 2005; Dahl and Hansen 2006), problem severity and needs

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 583

(Walker 1969; Sapat 2004) and the political composition of local councils (Berry and Berry

1990; Shipan and Volden 2006). Political entities do not act in a vacuum. On the contrary,

most political entities are highly interdependent, that is, the adoption of innovations may

foster emulation in the form of mimicry, learning or yard-stick competition (Shipan and

Volden 2006). Often such interdependence is tested in terms of regional or neighbouring

diffusion patterns (Berry and Berry 1990, 1999).

First, emulation is likely to trigger a regional pattern of adoption as proximity

increases the likelihood of interaction, joint formal organization and shared norms among

municipalities (Knoke 1982, p. 1316). Thus, the existence of formal regional municipal

organizations, employee transfers (Heugens and Lander 2007) and regional cooperation

in service provision are just a few illustrations of the factors driving regional mimetic

isomorphism (Dimaggio and Powell 1983). Thus, the argument is therefore basically a

relational one, stressing that the likelihood of adoption by imitation is a function of the

amount of interaction (Strang and Meyer 1993, p. 488), which, all things considered, makes

neighbouring or regional mimicry more likely (Dahl and Hansen 2006, p. 449).

Second, emulation may take the form of learning. That is, to look for innovations which

have succeeded elsewhere. Often political entities learn from nearby states as they can

more easily be analogized to proximate states, with which they often share economic or

political environments (Berry and Berry 1999). Third, as political entities compete with

mostly neighbouring states over citizens and firms, their adoption or non-adoption of a

specific innovation may be highly contingent on the adoption practices of neighbours.

In the case of CSCs, their adoption may be viewed as an improvement of the municipal

services, which could put pressure on neighbouring states to supply the service as well.

The presence of regional or neighbouring emulation has been confirmed empirically in a

municipal context in a number of studies (see, for example, Knoke 1982; Gregersen 2000;

Dahl and Hansen 2006). In a Danish municipal context regional emulation is particularly

likely due to the presence of regional municipal communities. These organizations, which

exist at the regional level, are interest organizations which have the coordination of

interests among the municipalities in a particular region as their primary responsibility

(Blom-Hansen 2002).

Hypothesis 2: Municipalities emulate other municipalities within their region.

Third, organizational wealth and capacity is generally believed to give room for

innovation (Mohr 1969; Walker 1969; O’Toole and Meier 2004; Ni and Bretschneider

2007). Walker (1969, p. 883) has argued that organizations with numerous ‘free floating’

or slack resources enjoy the luxury of experimenting with the adoption innovations, as

they are less vulnerable toward the risks of adopting such innovations. Thus, innovation

may be a ‘the politics of good times’ (Pallesen 2004). At the same time, municipal wealth is

a proxy measurement of the wealth of its citizens, whose demands to the service delivery

might be positively related to income (see, for example, Brown 1988).

Hypothesis 3: The greater the municipal wealth, the higher the likelihood of adoption.

Another factor often debated in the literature is organizational size (Walker 1969; Dahl

and Hansen 2006). A large municipality should increase the likelihood of adoption, since

it often has a greater organizational capacity to do so (Walker 1969; Moon and Norris

2005). In addition, there is a potential economy of scale, since fixed costs are spread over

a large number of citizens. On the other hand, greater organizational capacity might lead

large municipalities to develop idiosyncratic organizational forms. In the case of CSCs,

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

584 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

the need for a coordinating centre is greater in a large administration than in a small one.

The organizational size is also an important control for administrative professionalism

(Walker 1969), since the concentration of professionals is greatest in the largest cities (Dahl

and Hansen 2006).

Hypothesis 4: The larger the organizational size, the higher likelihood of adoption.

Furthermore, the possible need for solving a problem may drive the adoption of inno-

vations (Walker 1969; Gray 1973; Gregersen 2000). In the case of CSCs a number of factors

may be seen indicating ‘problem severity’ or a genuine ‘need’ for the one-stop-government

service provided by CSCs. This would be the case for municipalities. The coordinating

and integrating functions of CSCs would be of greatest benefit in municipalities with

large groups of weak clients, as they typically have more frequent contact with the

administration and have a greater need to be guided through bureaucratic procedures.

Hypothesis 5: The greater need for the specific innovative organizational form, the

higher likelihood of adoption.

Finally, ideological factors are regularly studied in the policy diffusion literature, where

party politics or interest organization pressure easily can be identified (see, for example,

Berry and Berry 1990; Shipan and Volden 2006). NPM reforms in general have been

associated with a liberal ideology (Christensen et al. 2007). One might argue that CSCs are

more in line with the conservative-liberal programme of generating a more efficient, user-

friendly public service, which was initiated with the Danish governmental modernization

programme in 1982.

Hypothesis 6: The more conservative/liberal a municipality is, the higher is its likeli-

hood of adoption.

ESTIMATION

In order to estimate the effects of the covariates on the probability of adopting CSCs, the

most appropriate framework is an event history model with a binary dependent variable

(Beck et al. 1998; Beck 2001). The unit of analysis is the individual municipality. The

dependent variable, the diffusion of CSCs, is a binary variable denoting whether or not a

CSC was established in the municipality a given year (Laursen 2006). The advantage of

such an analysis is not only that it is possible to model covariates but also that it exploits

the variation across the entire period.

The event history model is estimated with logistic regression where the value 1 is given

for the dependent variable in the year the CSC is adopted. In all previous years, the

dependent variable is zero for the case. After adoption, the given municipality drops out

of the analysis. If, for instance, a municipality adopts after nine years, it appears as nine

observations in the analysis, scoring 0 each of the first eight years and 1 in year nine. What

is modelled in the event history model is if and when a municipality adopt – a positive

logistic coefficient implies that the covariate is positively correlated with adoption and

vice versa. The model thus exclusively relates to transfer of the organizational form. That

is, the statistical model informs us about how certain covariates affect the probability of

adopting CSC, but not how CSC is transformed and translated afterwards (Clark 1985;

Berry and Berry 1999, p. 189).

A challenge in the binary choice event history models is modelling temporal depen-

dence. Since we are only interested in the coefficients of the substantive variables and not

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 585

the hazard rate per se, an appropriate way to deal with this problem is to include temporal

dummies as suggested by Beck et al. (1998, p. 1271). The relevance of temporal dummies

in our specification is justified by a likelihood ratio test of the joint significance of the

dummies (p < .05).

MEASURES

As commonly done in the diffusion literature (see, for example, Sapat 2004; Dahl and

Hansen 2006; Yang 2007; Teodoro 2009), the dependent variable, adoption of CSCs, is

based on self-reporting by the municipalities, that is, when a municipality reported to

have opened its first CSC. The drawback of this measure is the organization may develop

gradually. There may be an element of judgement in defining precisely when the CSC

was actually formed. This is likely to cause some random error in the dependent variable,

which can decrease the efficiency of the estimates (King et al. 1994). However, the results

would still be unbiased apart from the unlikely case that the judgment is correlated with

our key independent variables. The uncertainty induced by the measurement challenges

is something we share with most studies in the field (see, for example, Sapat 2004; Dahl

and Hansen 2006; Yang 2007; Teodoro 2009).

The ‘administrative professionals hypothesis’ (hypothesis 1) is measured by the number

of DJØF members per 1000 capita in the municipality. DJØF is a trade union that organizes

most employees within the fields of law, administration, state governance, research,

education, communication, economics, political and social science, that is, administrative

professionals in the municipal context. We include all DJØF employees, regardless of

whether they are managers or consultants, since our proposal causal operators do not

depend on the professionals occupying a managerial position. The indicator is directly

calculated on the basis of DJØFs own register of members. It should be noticed that the

percentage of organization is very high and that trade union membership is therefore a

very good indicator of the level of administrative professionals in the municipalities.

Though their educational background at first seem diverse, DJØF members are generally

recruited for similar executive positions or specialized functions, and are assigned to tasks

such as long term planning, evaluation and fiscal monitoring. Hence, in the context

of the municipal job market, they may be described as a relatively unified occupational

profession. At the same time, administrative professionals are a rather exclusive profession

in the municipal organizational field. Of the approximately 360,000 municipal employees

in 1998, less than 0.5 per cent were administrative professionals.

In order to avoid spuriousness in the estimation of the ‘administrative professionals’

effect, a number of specific control variables for hypothesis 1 are added to the model. First,

‘public employees’ and ‘bureaucrats’ separate the explanatory power of administrative

professionalism from other distinct characteristics of the municipal workforce. Second,

the level of education of inhabitants in a municipality is also included to preclude the

possibility that an association between administrative professionalism and the adoption

of CSCs is a spurious reflection of population-specific variables. It is indeed plausible that

a highly educated citizenry simultaneously leads to a professionalized administration and

a positive atmosphere for innovations.

In order to operationalize the regional emulation hypothesis (hypothesis 2), a variable

is constructed to measure the cumulative percentage of municipalities in a region which

had adopted CSCs prior to the year in question. The idea is the more CSCs in a region;

the greater will be the pressure for an individual municipality to create its own CSC.

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

586 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

Hence, the variable basically measures a cumulative regional pressure, highlighting the

already mentioned interaction argument for regional mimicry. Though regional emulation

seems particularly likely in a Danish context due to the presences regional municipal

communities, we also include a similar variable for the percentage of neighbours which

had adopted CSCs to control for the potential influence of proximity.

Economic wealth (hypothesis 3) is measured by municipal taxation per capita (after

governmental redistribution), controlled for per capita expenses (Ministry of the Interior

and Health 2008). Expenditures per capita are included as a control, since high municipal

taxation revenue in itself may not guarantee a surplus, if the municipality also has

high costs. The organizational size hypothesis (hypothesis 4) is easily operationalized

with population size data from official statistics (2008). A similar operationalization for

organizational size has previously been applied in both an American (Moon and Norris

2005) and Danish (Dahl and Hansen 2006) municipal context.

As for the need hypothesis (hypothesis 5), a social indicator, the so-called ‘social index’,

is added to the model (Ministry of the Interior and Health 2008). The social index is a

government issued summary measure of social conditions in the municipality, capturing

among other things the number of unemployed, immigrants, ghettoes and so on. A coor-

dinating centre, such as a CSC, is of greatest benefit in a municipality where we can expect

many contacts with the administration and where the clients have complex problems.

Weak clients typically have more frequent contact with the administration and have a

greater need to be guided through bureaucratic procedures. Furthermore, they often have

more complex problems, requiring a coordinated service, which CSCs can deliver. Thus,

one would expect municipalities with the greatest number of ‘weak clients’ with complex

problems to have a greater tendency to set up a CSC. A similar explanation has shown

explanatory power in a study of the diffusion of organizational changes in the social ser-

vice administration among municipalities (Gregersen 2000). In order to capture possible

reversed effects on the adoption of CSCs where there are many ‘weak clients’ a squared

version of the social index is also entered in to the model. Municipal size in square kilome-

tres is also included (Ministry of the Interior and Health 2008) as the need for a CSC should

intuitively be greater in a municipality with a large area. CSCs are not necessarily situated

at the city hall but are sometimes used as disaggregated access points to the public sector.

The need for alternative access points increases when distances are greater, since the time

cost to citizens of physically accessing the administration rises with the average distance.

Finally, as an operationalization of the ideological factor (hypothesis 6), the share of

the vote for the liberal/conservative parties in the last local election is entered into the

model. This controls for possible ideological reasons for adoption. Summary statistics for

the variables applied in the analysis are given in table 1. A full correlation matrix can be

found in the appendix. It should be noted that, for most of the independent variables

(except ideology and regional imitation), data was typically only available for the last

13 years under investigation. To avoid losing cases, we imputed 1987–1992 data simply

by using the value of the last available year. This strategy can be criticized from the

perspective that the variables will probably be slightly attenuated. If control variables are

estimated with error, the main independent variables may pick up some of the variance,

leading to anti-conservative evaluations of the hypotheses.

In the present case, this should not be a problem. Our main independent variable,

the ratio of administrative professionals, was among the variables with imputed years.

Hence, the estimate should, if anything, be attenuated, leading to a conservative hypothesis

test. In order to avoid any uncertainty, we ran a regression excluding 1987–1992 with

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 587

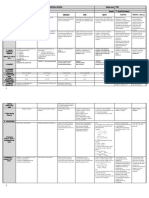

TABLE 1 Summary statistics for the variables

Variable Variable type Mean Std. Dev. Min Max N

Adoption of CSCs Dependent variable .033 .179 0 1 3949

Administrative professionals Hypothesis 1 .204 .185 0 1.51 3931

Public employees per capita Extra control for H1 16.3 2.87 11.9 31.3 3949

Bureaucrats per capita Extra control for H1 2.37 .502 1.45 5.52 3949

Education level Extra control for H1 13.5 4.77 6.8 40.8 3949

Regional imitation Hypothesis 2 18.0 16.5 0 95 3949

Neighbouring imitation Extra control for H2 .191 .245 0 1 3949

Tax base per capita (1000s) Hypothesis 3 109 12.4 95.2 155 3949

Expenses per capita (1000s) Extra control for H3 32.9 8.43 20.7 68.0 3949

Inhabitants (1000s) Hypothesis 4 17.7 40.6 2.15 501.7 3949

Social index Hypothesis 5 .760 .256 .35 2 3949

Area (1000s) Hypothesis 5 .160 .092 .009 .564 3949

Conservative/liberal share of vote Hypothesis 6 .425 .132 0 .774 3949

substantively identical results for all variables of primary interest. The professionalism

coefficient even increased by more than 50 per cent, as we will return to in the next section.

Thus, the results are robust to non-imputation and even seem to be conservative for our

main dependent variable.

ANALYSIS

Now the analysis of the diffusion for the period under investigation (1987–2005) can be

carried out. As indicated above, the model is estimated by logistic regression added tem-

poral dummies (Beck 2001) (see table 2). Due to the unbalanced nature of the dependent

variable, with only 3.3 per cent of the cases scoring the value one, we also ran rare-events

corrected logit, implemented by the ReLogit package in Stata 9 (King and Zeng 2001). This

did not make any substantial difference to the results in table 2. Furthermore, the main

independent variables of interests are very robust against alternative specifications. We

experimented with a range of alternative controls for economic surplus and bureaucrats

but the administrative professionalization and the regional imitation variables remained

stable around 1.3 and .02, respectively.

The analysis provides robust evidence in favour of the ‘administrative professionals’

hypothesis (hypothesis 1): the more professionalized an administration is, the higher the

likelihood of adoption of CSCs. Figure 2 illustrates the likelihood of adoption a given year

as the DJØF variable moves from its minimum to its maximum.

As indicated above, the ‘administrative professional’ variable is imputed for the early

part of the period due to lack of data. This might result in a slightly attenuated estimate.

When only 1993–2005 are analysed, the coefficient increases to 2.22 (standard error .645)

and the marginal effect to .041. This indicates that our imputation of the missing values is

conservative with respect to hypothesis 1. We also tried only to include only those DJØF

members occupying a managerial position. In that case the effect dropped dramatically

and became statistically insignificant. This implies that it is professionalization of the

administration as such which matters and not professionals occupying a superior position.

The analysis provides strong support for our assumption that administrative profes-

sionals, due to their distinct analytical knowledge, skills and incentives facilitate the

adoption of innovations. Unfortunately, the data at hand does not allow us directly to

distinguish between the unique effects of the three proposed causal operators but they

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

588 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

TABLE 2 Determinants of diffusion of CSCs, 1987–2005

Coefficient (b) Marginal effects

Administrative professionals (H1) 1.34∗ (.548) .023

Public employees per capita (control) .094 (.093) .002

Bureaucrats per capita (control) −.883∗ (.378) −.016

Education level (control) .001 (.023) .0000

Regional imitation (H2) .022∗ (.009) .0004

Neighbour imitation −.028 (.499) −.0005

Tax base per capita (1000s) (H3) .044∗ (.017) .0008

Expenses per capita (1000s) (control) −.009 (.040) −.0002

Inhabitants (1000s) (H4) −.003 (.002) −.0001

Social index (H5) 6.76∗∗∗ (1.85) —

Social index squared (H5) −2.38∗∗ (.847) —

Area (1000s) (H5) 2.03 (1.26) .036

Conservative/liberal share of votes (H6) 1.66 (.945) .029

Intercept −14.6∗∗∗ (2.60)

N 3931

log likelihood −498.9

LR χ-squared 151.1

Pseudo r2 -squared (McFadden) .132

Note: The coefficients in the left column are the unstandardized logistic coefficients. Standard errors are shown

in parentheses. In the right column, marginal effects with all variables at their means are shown (social

index squared held at the mean of social index squared). Temporal dummies are not shown due to space

considerations but were jointly significant at p < .05. We ran regressions with and without the municipalities of

Copenhagen and Frederiksberg due to their dual status as municipalities and regions. The results did not differ

substantially. The municipality of Bornholm was excluded, since it underwent a major amalgamation during

the period. Multicollinearity was evaluated using Stata ‘collin’. Apart from the squared term, some signs of

multicollinearity can be found due to the strong correlation between expenses per capita (the only variable apart

from the squared term with a VIF above 10) and public employees per capita (see also table A1 in the appendix).

However, none of the variables changed significance levels when the other was excluded from the specification.

Significance levels: ∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗ p < 0.01; ∗∗∗ p < 0.001.

are all plausible operators in the case of Danish CSCs. The knowledge factor fits well

with findings in the contracting out literature, where administrative professionals have

been found to be instrumental for the contracting process because of its complexity

(Bhatti et al. 2009). In the present case complexity is caused by the risk and uncertainty

related to innovations, as they are defined in terms of being a sort of disjuncture from

the standing operation procedures and routines within an organization (Roberts 1992,

p. 57). Clearly, administrative professionals are widely perceived to have the skills and

knowledge to adopt and successfully implement innovations. Accordingly, this has been

the argument underlying the increasing administrative professionalization of the Danish

municipalities’ top-level bureaucracies in the period under study (Munck 2003; Lykkebo

2006). Interestingly, the results hold, even though the general number of public employees

and bureaucrats are explicitly controlled for. Hence, the relationship cannot be attributed

to the general size of the administration or bureaucratic capacity as has been argued to

matter in some of the previous literature (Walker 1969; Sapat 2004). On the contrary,

the finding highlight that one should look closer at how this bureaucratic capacity is

compounded of distinct groups with varying degrees of professionalism. This need for

‘decomposing’ the different bureaucratic capacities has also been found in a recent study

of the correlates of contracting out (Bhatti et al. 2009).

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 589

.1 .08

Probability of adoption

.02 .04 0.06

0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1

Administrative professionals

Predicted probability 95% upper limit

95% lower limit

FIGURE 2 Computed effect of administrative professionals variable from its minimum to maximum (confi-

dence intervals are calculated by the delta method using SPost for Stata).

Furthermore, we argued that administrative professionals may enhance their profes-

sional reputation and career possibilities through the successful adoption of professionally

approved innovations. Hence, besides the ability to innovate, the finding indicates that

administrative professionals may have significant incentives for successfully seeking the

adoption of innovations. The incentives operator proposed by Teodoro (2008, 2009), that

administrative professionals gain traction in the adoption of innovations when job market

characteristics provide them with incentives for bureaucratic entrepreneurship, seems a

particularly plausible case. It resonates well with the administrative professionals in a

Danish municipal context, who are recruited into the municipalities from outside and

are, as such, expected to be able to contribute with something new and innovative. The

traditional municipal bureaucrat was typically trained within the municipal organization

or in institutions specifically established to feed the municipal job market, but in contrast

administrative professionals have much less constrained qualifications and job market

possibilities: They are university educated and recruited for both the private and public

sector. As such their skills are expected to differ from those present inside the organization.

Hence, administrative professionals may have strong incentives to signal their credentials

through the adoption of innovations.

Finally, we argued that the finding that administrative professionals matter is probably

less due to professional norms and networks, which in many empirical studies have

been identified as important sources of institutional or policy innovations (Balla 2001;

Yang 2007). That is, professional socialization motivates administrators to pursue their

professions’ favoured innovations (Brehm and Gates 1997). Functionally integrated small

units (FISUs) have been seen as a solution to problems of fragmentation and are therefore

strongly supported by public administration experts, underscoring the crucial role of

integration for achieving citizen or customer-oriented government (Fountain 1994; Seidle

1995; Bent et al. 1999). This means that the model should hold a good deal of legitimacy

among certain professionals. This being said, the norms and network argument is

weakened for theoretical reasons by the fact that administrative professionals are only

unified in terms of occupational status and not educational background, which may cover

many different social sciences with possible conflicting norms and networks. For instance,

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

590 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

economist and lawyers may have very different norms on matters concerning a trade-off

between efficiency and legal rights. This argument would be in line with empirical studies,

which have found no significant variations in leadership values between administrative

professionals and other municipal managers (Dahler-Larsen and Ejersbo 2003).

Though the main focus of the analysis was public labour and administrative pro-

fessionals in particular, interesting findings can be extracted from the investigation of

alternative hypotheses derived from the general diffusions of innovations literature. The

regression provides evidence in favour of the regional emulation hypothesis (hypothe-

sis 2), which suggested mimicry, learning or competition to foster innovations to cluster

geographically. The results support the findings of, for instance, Dahl and Hansen

(2006) by suggesting that CSCs diffuse in regional clusters, even when other factors

are controlled for, that is, regions have strong independent explanatory power (see

also Knoke 1982; Gregersen 2000). It should be noted that the result is highly reliant

on an appropriate specification of the model to preclude the possibility that apparent

regional imitation is due to homogeneity within regions. To take this possibility into

account, social and economic variables were thoroughly controlled for, while the neigh-

bouring imitation variable precludes the possibility that the effect is merely due to local

imitation.

Also the taxation variable is positive (hypothesis 3). The results are interesting, since

they indicate that adoption can be associated with the ‘politics of good times’ (Pallesen

2004). This means that municipalities with the greatest resources/capacity adopt. Similar

findings have been made by Moon and deLeon (2001), showing that reinvention pro-

grammes are not typically promoted by poorer municipalities. Conversely, it contradicts

earlier findings of the spread of bureaucratic standards in a Danish local government

setting (Dahl and Hansen 2006). Nevertheless, the conclusion that wealth and capacity in

the most general terms increases the likelihood of innovating is probably the most well

documented in the literature (Berry and Berry 1999).

There is no evidence in favour of the population size hypothesis (hypothesis 4). This

is contrary to much of the existing literature (Dahl and Hansen 2006) and it may seem

surprising, since larger municipalities could have a greater need for coordinated services

and a greater capacity to provide them due to their ability to bear relatively high fixed

costs. Nevertheless, it is important to include this variable in the specification in order

to preclude that the effect of administrative professionals is a reflection of the higher

concentration of professionals in big cities.

There seems to be some evidence in support of the importance of the pure functional

pressure/need (hypothesis 5), since the municipalities with the most demanding clients

are more likely to set up CSCs when other relevant factors are controlled for. Hence,

need seems to matter. At first sight, this might seem paradoxical since it was established

earlier that the municipalities with the greatest surplus have the strongest tendency to

adopt. However, functional need and economic surplus/capacity are not necessarily

in opposition to each other, since a challenging clientele does not preclude economic

surplus. This is in line with Gregersen (2000) who has found a ‘need’ driven demand for

innovations to be important among later adopters in a municipal context. Finally, there

is no evidence that political ideology plays any role (hypothesis 6). This is not entirely

surprising, since local government politics in the Scandinavian countries is often seen as

less ideologically driven than national politics. Hence, adoption in the present case rather

seems to be a matter of professionalism and functional needs as well as capacity.

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 591

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the determinants of adoption indeed seemed to confirm the important role

of administrative professionals. The more professional a municipal administration is, the

higher the likelihood of adopting the CSC. These results add to the growing body of

literature arguing that professionalism matters due to knowledge (Mintrom 1997; Sapat

2004; Shipan and Volden 2006) incentives (Teodoro 2008, 2009) and norms (Moon and

deLeon 2001; Yang 2007). It is likely to be of great importance that the administrative

professionals are recruited from outside the municipalities in contrast to the traditional

municipal administrators who were largely trained on the job. This creates an incentive

for the professional administrator to demonstrate her ability to do something new and

innovative in the municipality. In addition, she may have distinct skills due to a longer and

more specialized education. This may be important in order to minimize the uncertainty

related risk from adopting innovations that occurs because innovations often entail a

disjuncture from the standing operation procedures and routines within an organization.

Though as both causal operators are plausible, it should be emphasized that this study

cannot tell us anything definitive about which of them that matters (the most). Here is a

clear motivation for further research on the impact of administrative professionals. Also,

the analysis focused exclusively on how administrative professionals affect the probability

of adopting CSC. A natural further step in the study of administrative professionals would

be to explore how the innovations are translated and transformed after their adoption.

Equally interestingly as the support for the main hypothesis, regional emulation was

also significant in the regression, indicating that a distinctively regional pattern was

pronounced over the examined period: even when neighbouring imitation was accounted

for. This is in line with the findings from the large body of literature examining mimicry,

learning or yard-stick competition in terms of regional or neighbouring diffusion patterns

(Berry and Berry 1990, 1999).

Two further alternative hypotheses were confirmed, namely the influence of organi-

zational wealth/capacity and need driven diffusion. The former result resonates with

Walker’s (1969, p. 883) argument that organizations with slack resources can experiment

with innovations, since they are less vulnerable toward the risks of innovating. The later

result, however, indicates that need may also facilitate innovation (Walker 1969; Gray

1973; Gregersen 2000), as it turned out that municipalities with the greatest need for one-

stop-government services also have the highest likelihood of adopting CSCs. The results

indicate that need and capacity are not mutually exclusive but can affect innovation

simultaneously.

A vital question is the broader scope for our findings. In which contexts are they likely

to apply? What we have studied is the spread of an organizational form, not a policy idea.

The importance of administrative professionals should be greatest in cases where the

administration has some leverage in the political system (Shipan and Volden 2006). Diffu-

sion of organizational forms and administrative practices are examples of that, since they

are typically relatively depoliticized. Our findings, however, are not necessarily restricted

to these areas; since administrators may play facilitating or restricting roles even in areas

that are highly politicized (for instance administrators play an important role in part of

the contracting out literature; see, for example, O’Toole and Meier 2004, Bhatti et al. 2009).

It is our hope that future research will continue to examine administrative professionals

in the context of other innovations in order to further examine the variables and their

underlying mechanisms.

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

592 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank the Danish Independent Research Council which provided the funding for

this study. Earlier versions of the article were presented at the Scancor 20th Anniversary

Conference, Sessions VII, Panel: Analysing organizational change in the public sector,

Stanford University, California, November 21–23, 2008 as well as at internal seminars

at the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen (May 2008) and at the

Danish Institute of Governmental Research (September 2008). We thank all the partici-

pants for their comments. Our gratitude also goes to Kasper M. Hansen, Kurt Houlberg,

Søren Winter, Barry Bozeman, Eskil Heinesen and the Journal’s referees for intriguing

suggestions. Michael Laursen and DJØF graciously provided access to their data on CSCs

and administrative professionals, respectively. The usual disclaimer applies.

REFERENCES

Andersen, L.B. 2005. Offentligt ansattes strategier: Aflønning, arbejdsbelastning og professionel status for dagplejere, forlkeskolelærere og

tandlæger. Aarhus: Politica.

Andersen, L.B. and L.H. Pedersen. 2010. ’Public Service Motivation and Professionalism’, 14. IRSPM Conference, Bern, 7–9

April.

Balla, S.J. 2001. ‘Interstate Professional Associations and the Diffusion of Policy Innovations’, American Politics Research, 29, 3,

221–45.

Beck, N. 2001. ‘Time-series-cross-section-data: What Have We Learned in the Past Few Years?’, Annual Review of Political Science,

4, 271–93.

Beck, N., J.N. Katz and R. Tucker. 1998. ‘Taking Time Seriously: Time-series-cross-Section Analysis with a Binary Dependent

Variable’, American Journal of Political Science, 42, 4, 1260–88.

Bent, S., K. Kernaghan and B.D. Marson. 1999. Innovations and Good Practices in Single-Window Service. Ottawa: CCMD.

Berry, F.S. and W.D. Berry. 1990. ‘State Lottery Adoptions as Policy Innovations – An Event History Analysis’, American

Political Science Review, 84, 2, 395–415.

Berry, F.S. and W.D. Berry. 1999. ‘Innovation and Diffusion Models in Policy Research’, in P. Sabatier (ed.), Theories of the Policy

Process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 169–200.

Bhatti, Y., A.L. Olsen and L.H. Pedersen. 2009. ‘The Effects of Administrative Professionals on Contracting Out’, Governance, 22,

1, 121–37.

Blom-Hansen, J. 2002. Den fjerde statsmagt? Kommunernes Landsforening i dansk politik. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Brehm, J. and S. Gates. 1997. Working, Shirking, and Sabotage: Bureaucratic Response to a Democratic Public. Ann Arbor, MI:

University of Michigan Press.

Brown, J.C. 1988. ‘Coping with Crisis – the Diffusion of Waterworks in Late 19th-Century German Towns’, Journal of Economic

History, 48, 2, 307–18.

Budros, A. 2004. ‘Causes of Early and Later Organizational Adoption: The Case of Corporate Downsizing’, Sociological Inquiry,

74, 3, 355–80.

Christensen, T., A.L. Fimreite and P. Lægreid. 2007. ‘Reform of the Employment and Welfare Administrations – The Challenges

of Co-coordination Diverse Public Organizations’, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 73, 3, 389–408.

Clark, J. 1985. ‘Policy Diffusion and Program Scope: Research Directions’, Publius, 15, 4, 61–70.

Dahl, P.S. and K.M. Hansen. 2006. ‘The Diffusion of Standards – The Importance of Size, Region and External Pressure’, Public

Administration, 84, 2, 441–59.

Dahler-Larsen, P. and N. Ejersbo. 2003. Djøficering–myte eller realitet? Aarhus: Magtudredningen.

Dimaggio, P.J. and W.W. Powell. 1983. ‘The Iron Cage Revisited – Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in

Organizational Fields’, American Sociological Review, 48, 2, 147–60.

Fountain, J.E. 1994. Customer Service Excellence. Using Information Technologies to Improve Service Delivery in Government. Strategic

computing and Telecommunications in the Public Sector. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gray, V. 1973. ‘Innovation in States – Diffusion Study’, American Political Science Review, 67, 4, 1174–85.

Gregersen, O. 2000. ‘Organisationsforandringer i kommunale socialforvaltninger’, in Forandringer i teori og praksis. Copenhagen:

Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forlag, pp. 215–38.

Heugens, P. and M.W. Lander. 2007. Testing the Strength of the Iron Cage: A Meta-Analysis of Neo-Institutional Theory. Erasmus

Universität Rotterdam, ERIM Report Series Research in Management.

King, G., R.O. Keohane and S. Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

King, G. and L.C. Zeng. 2001. ‘Explaining Rare Events in international Relations’, International Organization, 55, 3, 693–715.

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE PROFESSIONALS AND DIFFUSION 593

Knoke, D. 1982. ‘The Spread of Municipal Reform – Temporal, Spatial, and Social Dynamics’, American Journal of Sociology, 87,

6, 1314–39.

Kubicek, K. and M. Hagen. 2001. One-stop-government in Europe: An Overview. Bremen: University of Bremen.

Laursen, M. 2006. Legitimerende symbol eller effektiviserende redskab? – en analyse af spredningen af kommunale servicecentre i

Danmark. Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen.

Local Government Denmark. 2006. Guide om etablering af borgerservicecentre – Til kommunalbestyrelsen og ledelsen. Copenhagen:

Local Government Denmark.

Lykkebo, O.B. 2006. Kommunerne professionaliserer i højt tempo (http://www.djoef.dk/online/view_SHTML?ID=11130&attr_

folder=F), accessed 30-01-2009.

Ministry of Interior and Health. 2008. De Kommunale Nøgletal. Copenhagen: Ministry of Interior and Health.

Mintrom, M. 1997. ‘Policy Entrepreneurs and the Diffusion of Innovation’, American Journal of Political Science, 41, 3, 738–70.

Mizruchi, M.S. and L.C. Fein. 1999. ‘The Social Construction of Organizational Knowledge: A Study of the Uses of Coercive,

Mimetic, and Normative Isomorphism’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 4, 653–83.

Mohr, L.B. 1969. ‘Determinants of Innovation in Organizations’, American Political Science Review, 63, 1, 111–26.

Moon, M.J. and P. deLeon. 2001. ‘Municipal Reinvention: Managerial Values and Diffusion among Municipalities’, Journal of

Public Administration Research and Theory, 11, 3, 327–51.

Moon, M.J. and D.F. Norris. 2005. ‘Does Managerial Orientation Matter? The Adoption of Reinventing Government and

E-government at the Municipal Level’, Information Systems Journal, 15, 1, 43–60.

Munck, L. 2003. DJØFernes jobmuligheder i den (amts)kommunale sektor–en kvalitativ og kvantitativ undersøgelse. Copenhagen:

Danmarks Jurist- og Økonomforbund.

Ni, A.Y. and S. Bretschneider. 2007. ‘The Decision to Contract Out: A Study of Contracting for E-government Services in State

Governments’, Public Administration Review, 67, 3, 531–44.

O’Toole, L.J. and K.J. Meier. 2004. ‘Parkinson’s Law and the New Public Management? Contracting Determinants and Service-

Quality Consequences in Public Education’, Public Administration Review, 64, 3, 342–52.

Pallesen, T. 2004. ‘A Political Perspective on Contracting Out: The Politics of Good Times. Experiences from Danish Local

Governments’, Governance, 17, 4, 573–87.

Pedersen, L.H. 2009. Med borgeren I centrum–Politisk forandring, forvaltningsmæssige hensyn og fordelingsmæssige konsekvenser af

borgerservicecentrene I Danmark. Copenhagen: AKF forlaget.

Rabe, B.G. 1999. ‘Federalism and Entrepreneurship: Explaining American and Canadian Innovation in Pollution Prevention and

Regulatory Integration’, Policy Studies Journal, 27, 2, 288–306.

Rainey, G.W. 1990. ‘Implementation and Managerial Creativity: A Study of the Development of Client-Centered Units in Human

Service Programs’, in D.J. Palumbo and D.J. Calistra (eds), Implementation and Policy Process: Opening up the Black Box. New

York: Greenwood.

Roberts, J. and M. Dietrich. 1999. ‘Conceptualizing Professionalism: Why Economics needs Sociology’, American Journal of

Economics and Sociology, 58, 4, 977–98.

Roberts, N.C. 1992. ‘Public Entrepreneurship and Innovation’, Review of Policy Research, 11, 1, 55–74.

Rogers, E. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th edn. New York: The Free Press.

Rowe, L.A. and W.B. Boise. 1974. ‘Organizational Innovation – Current Research and Evolving Concepts’, Public Administration

Review, 34, 3, 284–93.

Sapat, A. 2004. ‘Devolution and Innovation: The Adoption of State Environmental Policy Innovations by Administrative

Agencies’, Public Administration Review, 64, 2, 141–51.

Seidle, L.F. 1995. Rethinking the Delivery of Public Services to Citizens. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Shipan, C.R. and C. Volden. 2006. ‘Bottom-up Federalism: The Diffusion of Antismoking Policies from US Cities to States’,

American Journal of Political Science, 50, 4, 825–43.

Strang, D. and J.W. Meyer. 1993. ‘Institutional Conditions for Diffusion’, Theory and Society, 22, 4, 487–511.

Teodoro, M.P. 2008. Bureaucratic Mobility and the Adoption of Water Conservation Rates, paper presented at the annual meeting of

the MPSA Annual National Conference, Palmer House Hotel, Hilton, Chicago, IL, 3 April.

Teodoro, M.P. 2009. ‘Bureaucratic Job Mobility and the Diffusion of Innovations’, American Journal of Political Science, 53, 1,

175–89.

Teske, P. and M. Schneider. 1994. ‘The Bureaucratic Entrepreneur – The Case of City-Managers’, Public Administration Review,

54, 4, 331–40.

Tolbert, P.S. and L.G. Zucker. 1983. ‘Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal-Structure of Organizations – The Diffusion

of Civil-Service Reform, 1880–1935’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 1, 22–39.

Walker, J.L. 1969. ‘Diffusion of Innovations among American States’, American Political Science Review, 63, 3, 880–99.

Yang, S.-B. 2007. ‘The Diffusion of Organizational Practice: Institutional Factors Affecting the Adoption of Self-Managed Work

Teams’, International Review of Public Administration, 12, 1, 93–107.

Date received 26 April 2009. Date accepted 24 August 2009.

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

594 YOSEF BHATTI ET AL.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1 Correlation matrix for the variables included in the analysis

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13)

Adoption of —

CSCs (1)

Administrative 0.09 —

professionals (2)

Public employees (3) 0.06 0.35 —

Bureaucrats (4) 0.04 0.35 0.82 —

Education level (5) 0.08 0.27 0.24 0.18 —

Regional 0.07 0.22 0.57 0.54 0.20 —

imitation (6)

Neighbouring 0.05 0.11 0.42 0.39 0.20 0.68 —

imitation (7)

Tax base per capita 0.08 0.35 0.78 0.71 0.45 0.60 0.44 —

(1000s) (8)

Expenses per capita 0.06 0.35 0.93 0.80 0.20 0.60 0.42 0.77 —

(1000s) (9)

Inhabitants 0.05 0.38 0.14 0.10 0.80 0.07 0.08 0.08 0.16 —

(1000s) (10)

Social index (11) 0.09 0.26 0.24 0.25 0.15 0.15 0.10 0.06 0.38 0.39 —

Area (1000s) (12) −0.02 −0.02 −0.09 −0.27 −0.21 −0.22 −0.15 −0.17 −0.05 0.13 −0.18 —

Conservative/liberal 0.01 −0.04 −0.04 −0.07 0.18 0.10 −0.01 0.13 −0.08 −0.18 −0.36 0.04 —

share of vote (13)

Note: The coefficients are the pair-wise correlations.

Public Administration Vol. 89, No. 2, 2011 (577–594)

© 2010 The Authors. Public Administration © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

You might also like

- The Boat by Nam LeeDocument1 pageThe Boat by Nam LeeMichellee Dang0% (1)

- Engineering Mathematics Formula SheetDocument2 pagesEngineering Mathematics Formula Sheetsimpsonequal100% (1)

- New Steering Concepts in Public ManagementDocument11 pagesNew Steering Concepts in Public ManagementAlia Al ZghoulNo ratings yet

- The Buried Giant LitChartDocument57 pagesThe Buried Giant LitChartJanNo ratings yet

- Ob MicrosoftDocument20 pagesOb MicrosoftHoang LingNo ratings yet

- Baldersheim & Per Stava - 1993Document12 pagesBaldersheim & Per Stava - 1993akshat gargNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management-Collaborative and Network-Based Forms of StrategyDocument19 pagesStrategic Management-Collaborative and Network-Based Forms of StrategyNoemi G.No ratings yet

- Does Decentralization Affect Regional Public Spending in Italy?Document26 pagesDoes Decentralization Affect Regional Public Spending in Italy?Keuler HissaNo ratings yet

- Gender Mainstreaming As Transnational FL PDFDocument19 pagesGender Mainstreaming As Transnational FL PDFDavid SpiderKingNo ratings yet

- The Public Sector in An In-Between TimeDocument20 pagesThe Public Sector in An In-Between TimeMaurino ÉvoraNo ratings yet

- Due Date: 6 September 2021Document7 pagesDue Date: 6 September 2021Steven Matchaya0% (1)

- Collaborative Innovation in The Public Sector - New Perspectives On The Role of Citizens? Sjpa 21Document21 pagesCollaborative Innovation in The Public Sector - New Perspectives On The Role of Citizens? Sjpa 21tim fisipNo ratings yet

- Scalar Politics and Network Relations in The Governance of Highly Skilled MigrationDocument20 pagesScalar Politics and Network Relations in The Governance of Highly Skilled MigrationclaramcasNo ratings yet

- RP - Inovation ParadoxDocument14 pagesRP - Inovation Paradox'Jomar PadiernosNo ratings yet

- p2p Public Services Finland 2012Document132 pagesp2p Public Services Finland 2012HD49No ratings yet

- Smalskys-2017 - Civil Service SystemsDocument16 pagesSmalskys-2017 - Civil Service SystemscarolNo ratings yet

- Birokrasi Sosial MediaDocument22 pagesBirokrasi Sosial MediaFirli FarhatunnisaNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document32 pagesFULLTEXT01aNo ratings yet

- Onumah, Simpson The Accounting Discipline and The Government Budgeting ConceptDocument18 pagesOnumah, Simpson The Accounting Discipline and The Government Budgeting ConceptInternational Consortium on Governmental Financial Management100% (1)

- The Myths of E-Government: Looking Beyond The Assumptions of A New and Better GovernmentDocument17 pagesThe Myths of E-Government: Looking Beyond The Assumptions of A New and Better GovernmentKelas 701 DIV 2018No ratings yet

- Fascismoe EconomiaDocument36 pagesFascismoe EconomiaanarquistahistoriaNo ratings yet

- Dollery Grant 2011 Financial Sustainability and Financial ViabilityDocument21 pagesDollery Grant 2011 Financial Sustainability and Financial Viabilityeero.ylistaloNo ratings yet

- Eshag J E. (2008) Fiscal FederalismDocument8 pagesEshag J E. (2008) Fiscal FederalismAndré AranhaNo ratings yet

- Decentralization and Efficiency of Local Government: Maria Teresa Balaguer-Coll Emili Tortosa-AusinaDocument31 pagesDecentralization and Efficiency of Local Government: Maria Teresa Balaguer-Coll Emili Tortosa-AusinaSumesh C SNo ratings yet

- Government Information Quarterly: EditorialDocument12 pagesGovernment Information Quarterly: EditorialLeandro Manassi PanitzNo ratings yet

- W08-6 Ostrom DLCDocument22 pagesW08-6 Ostrom DLCMridu MehtaNo ratings yet

- On The Determinants of Local Government Performance: A Two-Stage Nonparametric ApproachDocument27 pagesOn The Determinants of Local Government Performance: A Two-Stage Nonparametric ApproachJoseLuisTangaraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4. Management Accounting in The Public SectorDocument59 pagesChapter 4. Management Accounting in The Public SectorMohaiminul Islam MominNo ratings yet

- Acrefore 9780190224851 e 129 PDFDocument25 pagesAcrefore 9780190224851 e 129 PDFAgZawNo ratings yet

- Public Service', Public Management' and The Modernization' of French Public AdministrationDocument23 pagesPublic Service', Public Management' and The Modernization' of French Public Administrationhari karyadiNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Social Innovation by Rethinking Collaboration, Leadership and Public GovernanceDocument12 pagesEnhancing Social Innovation by Rethinking Collaboration, Leadership and Public GovernanceNestaNo ratings yet

- The Optimum Size of Local Public Administration.: Jacob A. Bikker Daan Van Der LindeDocument24 pagesThe Optimum Size of Local Public Administration.: Jacob A. Bikker Daan Van Der LindeveronicaNo ratings yet

- Temporary Grant Programmes in Sweden and Central Government BehaviourDocument15 pagesTemporary Grant Programmes in Sweden and Central Government Behaviourrizal jingglongNo ratings yet

- The State, Democracy and The Limits of New Public Management: Exploring Alternative Models of E-GovernmentDocument14 pagesThe State, Democracy and The Limits of New Public Management: Exploring Alternative Models of E-GovernmentFadli NoorNo ratings yet

- Coordination For Policy in Transition Countries: Case of CroatiaDocument43 pagesCoordination For Policy in Transition Countries: Case of CroatiaZdravko PetakNo ratings yet

- Libfile Repository Content Holman, N Holman Effective Strategy Implementation 2013 Holman Effective Strategy Implementation 2012Document33 pagesLibfile Repository Content Holman, N Holman Effective Strategy Implementation 2013 Holman Effective Strategy Implementation 2012sapphire4uNo ratings yet

- Public Sector Innovativeness in Poland and in Spain Comparative AnalysisDocument16 pagesPublic Sector Innovativeness in Poland and in Spain Comparative AnalysisFerry SetyadhiNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Federalism NotesDocument142 pagesFiscal Federalism NotesPragya Shankar100% (1)

- Bekkers 1999Document13 pagesBekkers 1999ana mariaNo ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis of Decentralization Process in Croatia and DenmarkDocument12 pagesComparative Analysis of Decentralization Process in Croatia and DenmarkAnamaria PejkovicNo ratings yet

- Voice and Local Governance in The Developing World: What Is Done, To What Effect, and Why?Document43 pagesVoice and Local Governance in The Developing World: What Is Done, To What Effect, and Why?RuskanulMaarifNo ratings yet

- International Trade: Literature ReviewDocument2 pagesInternational Trade: Literature Reviewioana_doncaNo ratings yet

- Smalskys UrbanovicoxfordencDocument19 pagesSmalskys UrbanovicoxfordencMaha Sara Nada PhDNo ratings yet

- Government at A Glance 2019Document34 pagesGovernment at A Glance 2019Yulia RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Ache (2011) Nested Action SituationDocument60 pagesAche (2011) Nested Action SituationMarcos Rehder BatistaNo ratings yet

- Oates 202 NdgenfisfedDocument26 pagesOates 202 NdgenfisfedAlvaro MedinaNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Policy in Dutch Municipalities. Understanding The Process, Identifying Strengths andDocument23 pagesRisk Management Policy in Dutch Municipalities. Understanding The Process, Identifying Strengths andsalem3333No ratings yet

- 6 When Is Fiscal Decentralization Good For GovernanceDocument20 pages6 When Is Fiscal Decentralization Good For GovernanceCAMILLE MARTIN MARCELONo ratings yet