Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ostracism 1

Uploaded by

Shaheena SanaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ostracism 1

Uploaded by

Shaheena SanaCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Behavior and Personality, Volume 47, Issue 11, e8244

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8244

www.sbp-journal.com

Workplace ostracism and job performance: Meaning at work and family

support as moderators

Liwei Feng1, Jiapei Li2, Taiwen Feng3, Wenbo Jiang2

1

School of Business Administration, Inner Mongolia University of Finance and Economics, People’s Republic of China

2

School of Management, Northwestern Polytechnical University, People’s Republic of China

3

School of Economics and Management, Harbin Institute of Technology (Weihai), People’s Republic of China

How to cite: Feng, L., Li, J., Feng, T., & Jiang, W. (2019). Workplace ostracism and job performance: Meaning at work and family

support as moderators. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 47(11), e8244

Keywords

The negative relationship between workplace ostracism and employees’ workplace ostracism; job

job performance has received increasing attention from academia and performance; innovation;

in practice. However, little is known about the conditions under which meaning at work; family

these negative effects can be alleviated. We investigated whether member support; health

workplace ostracism simultaneously predicts in-role job performance care

and innovative job performance, as well as exploring the moderating

roles of meaning at work and family member support in these

relationships. Using data collected from 727 employees of 3 Chinese

hospitals, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis to

test our hypotheses. The results indicated that workplace ostracism

predicted both poor in-role job performance and low innovative job

performance. Moreover, high levels of family support moderated the

relationship between workplace ostracism and innovative job

performance. These results have implications for theoretical and

practical understanding of workplace ostracism.

Workplace ostracism is a ubiquitous phenomenon and refers to individuals’ perception that they are

ignored or excluded by others at work (Ferris, Brown, Berry, & Lian, 2008). Robinson, O’Reilly, and Wang

(2013) proposed an integrated model of workplace ostracism, including antecedents, outcomes, and

moderators of reactions to, and effects of, workplace ostracism, and found the pervasive assumption of

workplace ostracism appears to be well founded because of its negative impacts on employees’ behavioral

outcomes, such as job performance, organizational citizenship behavior, withdrawal, and workplace

deviance. The relationships between workplace ostracism and both in-role job performance and innovative

job performance or creativity have been extensively examined (Chung & Kim, 2017; Kwan, Zhang, Liu, &

Lee, 2018). However, how workplace ostracism simultaneously influences these two types of job

performance remains unclear. Indeed, a balance is needed when setting structural procedures to make work

performance predictable but at the same time allow for spontaneous innovation (Jiang, Chai, Li, & Feng,

2018). As such, our study is crucial as we sought to link workplace ostracism to both in-role job performance

and innovative job performance.

It has been argued that innovation is a job performance dimension (Harari, Reaves, & Viswesvaran, 2016).

Whereas in-role job performance can be defined by employees’ job descriptions, innovative job

performance relates to the generation, promotion, and realization of new ideas within a work role, work

group, or organization for benefiting in-role job performance (Janssen & Van Yperen, 2004). Indeed,

innovative employees are likely to seek out information and use it to discover and develop new ideas to

CORRESPONDENCE Wenbo Jiang, School of Management, Northwestern Polytechnical University, 127 West Youyi Road, Beilin

District, Xi'an Shaanxi, 710072, People’s Republic of China. Email: jiangwenbo@mail.nwpu.edu.cn

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved.

Feng, Li, Feng, Jiang

perform work tasks, which facilitates job performance.

In this study we used the job demands–resources (JD–R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) to explore

how workplace ostracism influences employees’ in-role and innovative job performance. According to this

model, job demands can trigger stress and job resources can compensate for this stress (Bakker &

Demerouti, 2007). Workplace ostracism may reduce the employee’s ability to respond to the demands of

work and may deplete his or her job-related resources, reinforcing the employee’s emotional exhaustion and

fostering disengagement. Consequently, we argued that workplace ostracism would be negatively associated

with the two types of job performance.

Although researchers have demonstrated some negative effects of workplace ostracism on job performance,

little is known about what employees can do to mitigate these detrimental effects (De Clercq, Ul Haq, &

Azeem, 2019). Being ostracized may block the capabilities and resources that employees can utilize to

generate and implement new ideas and perform tasks. Employees who are ostracized by peers within the

organization might turn to alternative sources of support. Thus, we argued that meaning at work and family

member support could mitigate the negative impacts of workplace ostracism on the two types of job

performance. Whereas meaning at work refers to the value, purposes, or goal that individuals attach to

working (Clausen & Borg, 2011), family member support is defined as the extent to which persons perceive

their support needs, including information and feedback, to be fulfilled by family members (Gottlieb &

Bergen, 2010).

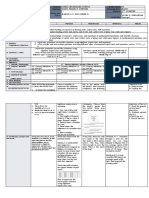

In sum, we sought to contribute to the literature on workplace ostracism by incorporating employees’ in-role

job performance and innovative job performance into one model. Further, we examined meaning at work

and family member support as potential boundary conditions under which the strength of the workplace

ostracism–job performance relationship could be attenuated. Finally, the relationship between workplace

ostracism and job performance has not been explicitly examined in the health-care environment that was

the context for our study. Our conceptual model is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual research model.

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 2

Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal

Theory Foundation and Research Hypotheses

Workplace Ostracism and In-Role Job Performance

Exposure to ostracism is a psychologically stressful and physically painful experience, impairing individuals’

ability to self-regulate and increasing the likelihood of outcomes such as social anxiety and poor in-role job

performance (Ferris et al., 2008). In the regulation process, the individual’s attentional resources are

directed toward rumination about causes and meanings of the ostracism event. According to the JD–R

model, a lack of job resources may hinder an employee’s motivation to accomplish his or her work-related

obligations (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001). When self-regulatory resources are

depleted, the resulting impairment in work effectiveness reduces in-role job performance. Thus, people who

perceive that they are the target of workplace ostracism may suffer emotional exhaustion and find

themselves less able to accomplish work-related duties and responsibilities.

Ostracized employees are likely to perceive themselves as belonging to the out-group rather than the in-

group. Being the target of workplace ostracism may decrease employees’ belongingness and organizational

identification (Gkorezis & Bellou, 2016). People with low levels of organizational identification are likely to

be perceived as less trustworthy, honest, and cooperative, which may negatively affect their in-role job

performance (Mao, Liu, Jian, & Zhang, 2018). Moreover, conflicts may arise when individuals hold

divergent values, interests, and beliefs, thus interfering with their task performance (Chung, 2015) and

inducing divergence in individuals’ interests or goals, which is negatively related to in-role job behavior and

performance (Van Quaquebeke, Zenker, & Eckloff, 2009). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a: Workplace ostracism will be negatively associated with employees’ in-role job

performance.

Workplace Ostracism and Innovative Job Performance

Workplace ostracism reduces the chance for social interaction with others along with reducing feelings of

belonging to and identifying with the organization, which negatively predicts innovative job performance

(Dotan-Eliaz, Sommer, & Rubin, 2009). When ostracized employees perceive that they are being excluded

by peers, they may feel “out of the loop” (Jones & Kelly, 2010); thus, despite being included in a group, they

are less likely to interact with other members. For example, ostracized employees tend to inhibit their

sharing of work-related information and to engage in knowledge-hiding behaviors (Zhao, Xia, He, Sheard, &

Wan, 2016). Sharing and exchanging work-related information among members may facilitate radical

innovation performance. According to the JD–R model, information sharing can contribute to the

replenishment of job resources (Nahrgang, Morgeson, & Hofmann, 2011). Thus, we believed that workplace

ostracism would negatively predict information-sharing intentions by distracting employees from

innovative job performance.

Workplace ostracism may cause employees to become emotionally exhausted, which undermines their

intrinsic motivation for creative idea generation (Chung & Kim, 2017). In the JD–R model it is stated that

high job demands foster emotional withdrawal and eventual disengagement from work (Tims, Bakker, &

Derks, 2013). Job demands are associated with energy depletion, whereby employees’ emotional resources

may be overstretched where there is workplace ostracism (Jahanzeb & Fatima, 2017). Employees who are

the target of workplace ostracism may fail to show high personal initiative and to seek out potential

opportunities (Zhao, Peng, & Sheard, 2013), leading to low levels of innovative job performance. As such, we

proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1b: Workplace ostracism will be negatively associated with employees’ innovative job

performance.

The Moderating Effect of Meaning at Work

Meaning at work has been perceived as an effective approach to buffering work stress by facilitating greater

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 3

Feng, Li, Feng, Jiang

motivation and an increased desire to exert oneself at work (Jung & Yoon, 2016). If employees have high

levels of meaning at work, they may maintain related resources and engage in sustained working, making

them resilient to workplace ostracism. Under such circumstances ostracized employees are encouraged to

maintain a sustained effort in work-related activities and innovation activities.

Conversely, employees with low levels of meaning at work may exhaust their energy budget and emotional

resources (Van Wingerden, Derks, & Bakker, 2017), increasing the possibility of burnout. In this case,

ostracized employees may withdraw from their usual work responsibilities and disengage from innovative

behavior. Thus, high levels of meaning at work may attenuate the negative influence of workplace ostracism

on job performance, and we formed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: Meaning at work will moderate the relationship between workplace ostracism and in-role

job performance, such that high levels of meaning at work will weaken the relationship.

Hypothesis 2b: Meaning at work will moderate the relationship between workplace ostracism and

innovative job performance, such that high levels of meaning at work will weaken the relationship.

The Moderating Effect of Family Member Support

Family member support can boost energy and resources related to creative work involvement, and reduce

stress that interferes with one’s ability to work (Menges, Tussing, Wihler, & Grant, 2017). Employees who

perceive high levels of support from family members are likely to experience energy and obtain extensive

resources. In this case, ostracized employees will still be motivated to invest the effort needed to perform

their usual tasks and generate innovative ideas.

Conversely, employees who perceive low levels of support from family members may lack energy and

resources (Menges et al., 2017). Under these circumstances they are prone to emotional exhaustion and

disengagement when coping with workplace ostracism. On the basis of the above argument, we formed the

following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Family member support will moderate the relationship between workplace ostracism and

in-role job performance, such that a high level of family member support will weaken the relationship.

Hypothesis 3b: Family member support will moderate the relationship between workplace ostracism and

innovative job performance, such that a high level of family member support will weaken the relationship.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The data used in this study were collected from hospitals in Beijing, Jinan, and Xi’an, China. Each of the

hospital locations reflects one of the three different levels in service industry development in China: Beijing

represents the most developed cities in China’s service industry; Jinan is a city with a prosperous, modern

service industry; and Xi’an has a relatively backward service industry.

First, under the guidance of the Municipal Health Commission, we contacted the human resources manager

of each hospital. Our project was approved by the designated authority within the hospitals and by ethics

committees. Employees were informed of the objectives of this research to encourage their willingness to

participate. Human resources managers prepared a list of employee names and the departments in which

they were employed. At each of the three hospitals 400 employees (including physicians and nurses) were

selected utilizing a random number generator. Survey forms were mailed to the human resources managers

and then delivered randomly to employees and their supervisors in a hermetically sealed package to ensure

anonymity. Only the researchers were able to access the information on the pairing relationships between

employees and their supervisors.

Second, we collected data in two waves: December 2015 and June 2016. All the participants were assured of

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 4

Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal

the confidentiality of their responses and that their personal information would not be revealed. To match

respondents over the two waves of the survey, each questionnaire was coded with an identification number

known only to the researchers. Finally, completed surveys were returned directly to the researchers in

sealed and preaddressed envelopes to ensure the authenticity of data.

The questionnaire was originally developed in English, then translated into Chinese by three independent

bilingual researchers by following the back-translation procedure to ensure that the translations were

precise (Feng, Huang, & Avgerinos, 2018; Taoketao, Feng, Song, & Nie, 2018). To improve the scale’s

reliability we conducted a pilot test with 12 physicians employed at two of the hospitals from which we

sourced our participants, whose responses were excluded from the practical data collection. They were

asked to review the questionnaire and provide feedback (Feng, Wang, Lawton, & Luo, 2019).

At Time 1 we asked 1,200 employees to report their gender, age, and tenure at the hospital, and their

perception of having been a target of workplace ostracism by peers, meaning at work, and family member

support. After deleting questionnaires with missing data, we received 756 usable responses (response rate =

63.00%). Six months later (Time 2) we sent 756 forms to supervisors who were asked to evaluate their group

members’ in-role job performance and innovative job performance. We received 727 usable questionnaires

at Time 2 that we matched with the equivalent employee questionnaire at Time 1 (response rate of

employees = 60.58% vs. response rate of supervisors = 96.16%). The average age of all participants (73.04%

women, 26.96% men) was 30.88 years (SD = 7.15, range = 18–64), and the average tenure was 8.92 years

(SD = 7.33, range = 0.5–40.9). Comparing the Time 1 and Time 2 responses, all t statistics were

nonsignificant, suggesting that nonresponse bias was not a major concern.

Measures

Workplace ostracism. Ten items adapted from Ferris et al. (2008) were utilized to measure workplace

ostracism. We changed the item “Others at work did not invite you or ask you if you wanted anything when

they went out for a coffee break” to fit the Chinese context so that it read “Others at work did not invite you

or ask you if you wanted anything when they went out for lunch.” Respondents rate the extent to which they

have experienced each item in the past 6 months, using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7

(always).

Job performance. Five items adopted from Janssen and Van Yperen (2004) were utilized to measure in-

role job performance. A sample item is “This worker always completes the duties specified in his/her job

description.” Immediate supervisors of employees indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with

statements about the quality and quantity of role-related activities, using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from

1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Nine items adopted from Janssen and Van Yperen (2004) were used to measure innovative job

performance. A sample item is “This employee creates new ideas for improvements.” Immediate supervisors

rate how often employees perform innovative work behaviors in the workplace, using a scale 7-point Likert

scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always).

Meaning at work. Seven items adopted from Duchon and Plowman (2005) were utilized to measure

meaning at work. A sample item is “I experience joy in my work.” Responses are made on 7-point Likert

scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Family member support. Six items adapted from Procidano and Heller (1983) and Westring and Ryan

(2010) were utilized to measure family member support. We adapted the item “My family supports my

decision to go here” to read “My family supports my decision to be a doctor/nurse.” We also added the item

“There is a member of my family I could go to if I were just feeling down, without feeling funny about it

later.” Responses are made on 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 5

Feng, Li, Feng, Jiang

Control variables. Age, tenure, and gender are likely to be associated with workplace ostracism (Fiset, Al

Hajj, & Vongas, 2017). To follow a normal distribution, age and tenure were controlled for in the subsequent

analyses by using the log of age (Jiang et al., 2018) and the log of self-reported years worked at the hospital

(Li, Feng, & Jiang, 2018). Gender was dummy coded as men = 1 and women = 0 (Wang, Feng, & Lawton,

2017).

Results

Construct Reliability and Validity

The reliability of the scale was evaluated using Cronbach’s α coefficients and composite reliability values

(see Table 1). All scales possessed adequate internal reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis was also

performed to verify the scales’ convergent and discriminant validity. The results showed that the five-factor

model fit the data well: chi square (df = 619) = 2722.13, root mean square error of approximation = .074,

nonnormed fit index = .96, comparative fit index = .97, standardized root mean square residual = .065. All

factor loadings were significant on the latent constructs they were designed to measure (see Table 1) with t

values greater than 2.0, indicating good convergent validity. We calculated the average variance extracted

(AVE) to check for discriminant validity. The square roots of AVE values along the diagonal were greater

than the correlations for all constructs in the lower left off-diagonal of the matrix, indicating good

discriminant validity.

Common Method Variance

To alleviate the potential threat of common method variance, we employed two post hoc procedures: First,

there was a 6-month interval between the two data collection times of predictors. Second, data used in this

study were collected from two groups of respondents—supervisors and employees—minimizing concerns

about sampling bias. The supervisors were asked to rate the effort, quality, and quantity of performance of

each of their employees. A separate form was used to gather predictors.

Relationship Between Workplace Ostracism and In-Role Job Performance

Hypotheses were tested using hierarchical multiple regression analysis with a three-step procedure (see

Table 3, Models 1–8). Table 3 shows that work ostracism predicted poor in-role job performance (Model 2),

supporting Hypothesis 1a. The coefficient associated with the work ostracism–meaning at work interaction

was nonsignificant (Model 4); thus, Hypothesis 2a was not supported. The coefficient associated with the

work ostracism–family member support interaction was nonsignificant (Model 4); hence, Hypothesis 3a

was not supported.

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 6

Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal

Table 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results for Study Constructs

Note. AVE = average variance extracted.

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 7

Feng, Li, Feng, Jiang

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between Constructs

Note. N = 727. Numbers in bold on the diagonal indicate the square root of average variance extracted.

* p < .05, ** p < .01.

Table 3. Hierarchical Regression Results

Note. N = 727. All coefficients are standardized, and variables were centered in the moderated regression

analysis. Gender: men = 1, women = 0.

* p < .05, *** p < .001.

Relationships Between Workplace Ostracism and Innovative Job Performance

Table 3 shows that work ostracism predicted employees’ poor innovative job performance (Model 6),

supporting Hypothesis 1b. The workplace ostracism–meaning at work interaction was nonsignificant

(Model 8); thus, Hypothesis 2b was not supported. The work ostracism–family member support interaction

was significant and positive (Model 8); hence, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 8

Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal

A simple slope test was conducted to plot the interaction effect of workplace ostracism and family member

support in predicting innovative job performance (see Figure 2). The relationship between workplace

ostracism and innovative job performance was significantly negative at a low level of family member

support (β = -.072, p < .05), but not at a high level of family member support (β = .045, ns). Thus,

Hypothesis 3b was further supported.

Figure 2. Joint moderating effects of meaning at work and family member support on the

relationship between workplace ostracism and innovative job performance.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine whether workplace ostracism can predict employees’ in-role and

innovative job performance, and to address meaning at work and family member support as moderators in

these relationships. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that workplace ostracism was related to both

poor in-role job performance and low innovation. As being ostracized depletes employees’ resources, a

reduction in access to valuable resources hinders the ability to fulfill all responsibilities required by their

job, and undermines their intrinsic motivation for developing new ideas. These results are consistent with

those of Chung and Kim (2017) and Ferris and colleagues (2008), who found that ostracism is negatively

related to in-role and innovative behavior.

Theoretical Implications

In accordance with our prediction, family member support moderated the relationship between workplace

ostracism and innovative job performance, as high levels of family member support weakened this

relationship. Our findings support those of Kaynak, Lepore, and Kliewer (2011), who reported that social

support improves family communication and relationships, reducing negative psychological outcomes

associated with violence. Family member support serves as a continuing replenishment of the resources

required in overcoming challenges. If employees experience workplace ostracism, perceived family member

support may replenish the affected employees’ resources, buffering the victims from a decrease in

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 9

Feng, Li, Feng, Jiang

psychological and physical well-being. Contrary to our expectation, the interaction of workplace ostracism

and family member support did not have a significant impact on in-role job performance. One possible

explanation is that exploring and developing innovative ideas needs more social support in terms of

providing employees with the space, time, and information than is required to perform in-role work (Birdi,

Leach, & Magadley, 2016). When employees perceive their families as supportive, they are better able to

cope with ostracism through acquiring alternative resources from their families; thus, the support of the

family weakens the negative influences of workplace ostracism on innovative rather than in-role job

performance.

Although Leung, Wu, Chen, and Young (2011) argued that having meaning at work allows people to adapt

more effectively to work stress and protects them against the impact of negative stressors, our hypotheses to

test these relationships were not supported. This can be explained in that the focus of meaningfulness is

primarily on responses to stress; however, experiencing traumatic life events may create a discrepancy

between people’s understanding of the event and their understanding of life satisfaction and personal

growth. As such, a stressful situation would threaten a person’s meaning at work if he or she is exposed to

traumatic life events.

Managerial Implications

This study has several implications for managers of organizations. First, they should monitor ostracism

behavior as well as its adverse impacts on employees’ psychological and physical well-being. If ostracized

individuals display higher levels of social anxiety, then managers can provide a face-to-face intervention that

helps assist them in their work behaviors. Managers should also be careful with their own relationships with

other organizational members because engaging in even slight ostracism may encourage employees to act in

a similar manner. Further, managers should address the importance of trust and cooperation among team

members to help employees cope with workplace ostracism and protect their psychological health. We also

recommend managers assist with replenishing the affected employees’ resources by, for example,

establishing formal family-supportive policies so that those family members who are actively involved in

supporting employees in better understanding ostracism can help to resolve the situation.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting our results. The supervisors’

subjective performance evaluation may be strongly associated with demographic variables (e.g., age, gender)

and personality traits (e.g., optimism, openness, and conscientiousness). Thus, an alternative measure of

job performance will need to be validated in future studies. Further, replication of the findings is limited by

the source of the data. The perception of meaning at work, work–family relationships, and work ostracism

may differ across different cultures. Further studies will be required to replicate our research in other

settings. Finally, future studies may benefit from the incorporating of other potential moderators, such as

emotional exhaustion and job burnout, to provide a more contextualized understanding of the experience of

being ostracized in the workplace.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund Project of China (17BGL107) for the project

Research on Job Stability of Chinese Enterprises Expatriating Mongolian and Russian Employees.

References

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 10

Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal

Birdi, K., Leach, D., & Magadley, W. (2016). The relationship of individual capabilities and environmental

support with different facets of designers’ innovative behavior. Journal of Product Innovation

Management, 33, 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12250

Chung, Y. W. (2015). The mediating effects of organizational conflict on the relationships between

workplace ostracism with in-role behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of

Conflict Management, 26, 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-01-2014-0001

Chung, Y. W., & Kim, T. (2017). Impact of using social network services on workplace ostracism, job

satisfaction, and innovative behaviour. Behaviour and Information Technology, 36, 1235–1243.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2017.1369568

Clausen, T., & Borg, V. (2011). Job demands, job resources and meaning at work. Journal of Managerial

Psychology, 26, 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111181761

De Clercq, D., Ul Haq, I., & Azeem, M. U. (2019). Workplace ostracism and job performance: Roles of self-

efficacy and job level. Personnel Review, 48, 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2017-0039

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model

of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512. https://doi.org/ckks28

Dotan-Eliaz, O., Sommer, K. L., & Rubin, Y. S. (2009). Multilingual groups: Effects of linguistic ostracism

on felt rejection and anger, coworker attraction, perceived team potency, and creative performance. Basic

and Applied Social Psychology, 31, 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530903317177

Duchon, D., & Plowman, D. A. (2005). Nurturing the spirit at work: Impact on work unit performance. The

Leadership Quarterly, 16, 807–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.008

Feng, T., Huang, Y., & Avgerinos, E. (2018). When marketing and manufacturing departments integrate:

The influences of market newness and competitive intensity. Industrial Marketing Management, 75,

218–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.06.007

Feng, T., Wang, D., Lawton, A., & Luo, B. N. (2019). Customer orientation and firm performance: The joint

moderating effects of ethical leadership and competitive intensity. Journal of Business Research, 100,

111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.021

Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the

Workplace Ostracism Scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 1348–1366.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012743

Fiset, J., Al Hajj, R., & Vongas, J. G. (2017). Workplace ostracism seen through the lens of power. Frontiers

in Psychology, 8, 1528. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01528

Gkorezis, P., & Bellou, V. (2016). The relationship between workplace ostracism and information exchange:

The mediating role of self-serving behavior. Management Decision, 54, 700–713.

https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-09-2015-0421

Gottlieb, B. H., & Bergen, A. E. (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic

Research, 69, 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001

Harari, M. B., Reaves, A. C., & Viswesvaran, C. (2016). Creative and innovative performance: A meta-

analysis of relationships with task, citizenship, and counterproductive job performance dimensions.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25, 495–511.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1134491

Jahanzeb, S., & Fatima, T. (2017). The role of defensive and prosocial silence between workplace ostracism

and emotional exhaustion. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2017, (1).

https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2017.17107abstract

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 11

Feng, Li, Feng, Jiang

Janssen, O., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2004). Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member

exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47,

368–384. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159587

Jiang, W., Chai, H., Li, Y., & Feng, T. (2018). How workplace incivility influences job performance: The role

of image outcome expectations. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources,57,

445–469.https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12197

Jones, E. E., & Kelly, J. R. (2010). “Why am I out of the loop?” Attributions influence responses to

information exclusion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1186–1201.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210380406

Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2016). What does work meaning to hospitality employees? The effects of

meaningful work on employees’ organizational commitment: The mediating role of job engagement.

International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 59–68.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.12.004

Kaynak, Ö., Lepore, S. J., & Kliewer, W. L. (2011). Social support and social constraints moderate the

relation between community violence exposure and depressive symptoms in an urban adolescent sample.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30, 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.3.250

Kwan, H. K., Zhang, X., Liu, J., & Lee, C. (2018). Workplace ostracism and employee creativity: An

integrative approach incorporating pragmatic and engagement roles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103,

1358–1366. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000320

Leung, A. S. M., Wu, L. Z., Chen, Y. Y., & Young, M. N. (2011). The impact of workplace ostracism in service

organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30, 836–844.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.01.004

Li, Y., Feng, T., & Jiang, W. (2018). How competitive orientation influences unethical decision-making in

clinical practices? Asian Nursing Research, 12, 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2018.07.001

Mao, Y., Liu, Y., Jiang, C., & Zhang, I. D. (2018). Why am I ostracized and how would I react? — A review of

workplace ostracism research. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35, 745–767. https://doi.org/

10.1007/s10490-017-9538-8

Menges, J. I., Tussing, D. V., Wihler, A., & Grant, A. M. (2017). When job performance is all relative: How

family motivation energizes effort and compensates for intrinsic motivation. Academy of Management

Journal, 60, 695–719. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0898

Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of

the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 96, 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021484

Procidano, M. E., & Heller, K. (1983). Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family:

Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11, 1–24.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00898416

Robinson, S. L., O’Reilly, J., & Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace

ostracism. Journal of Management, 39, 203–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312466141

Taoketao, E., Feng, T., Song, Y., & Nie, Y. (2018). Does sustainability marketing strategy achieve payback

profits? A signaling theory perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management,

25, 1039–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1518

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and

well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18, 230–240.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032141

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 12

Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal

Van Quaquebeke, N., Zenker, S., & Eckloff, T. (2009). Find out how much it means to me! The importance

of interpersonal respect in work values compared to perceived organizational practices. Journal of Business

Ethics, 89, 423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-0008-6

Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). The impact of personal resources and job crafting

interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56, 51–67.

https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21758

Wang, D., Feng, T., & Lawton, A. (2017). Linking ethical leadership with firm performance: A

multidimensional perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 95–109.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2905-9

Westring, A. F., & Ryan, A. M. (2010). Personality and interrole conflict and enrichment: Investigating the

mediating role of support. Human Relations, 63, 1815–1834. https://doi.org/dswxjt

Zhao, H., Peng, Z., & Sheard, G. (2013). Workplace ostracism and hospitality employees’ counterproductive

work behaviors: The joint moderating effects of proactive personality and political skill. International

Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.08.006

Zhao, H., Xia, Q., He, P., Sheard, G., & Wan, P. (2016). Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding in

service organizations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 59, 84–94.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.09.009

© 2019 Scientific Journal Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 13

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

You might also like

- Ariani 2012 PDFDocument11 pagesAriani 2012 PDFMichelle Elfreda JuangtaNo ratings yet

- Bem Estar Proprio e Engajamento No TrabalhoDocument12 pagesBem Estar Proprio e Engajamento No TrabalhoAdrianeNo ratings yet

- EJ1392623Document11 pagesEJ1392623tyrabialaNo ratings yet

- Workplace Ostracism: The Moderating Effect of Gender Differences On Job PerformanceDocument8 pagesWorkplace Ostracism: The Moderating Effect of Gender Differences On Job PerformanceTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- We SatisfactionDocument11 pagesWe SatisfactiongeoNo ratings yet

- Personality Traits and WorkaholismDocument17 pagesPersonality Traits and Workaholism079851292No ratings yet

- Ran Xiong e Yuping Wen - 2020 - Employees' Turnover Intention and Behavioral OutcoDocument8 pagesRan Xiong e Yuping Wen - 2020 - Employees' Turnover Intention and Behavioral OutcoAlexandreNo ratings yet

- Czarnota Bojarska2015Document12 pagesCzarnota Bojarska2015Iskhaq ZulkarnainNo ratings yet

- Work Engagement and Its Relationship With State and Trait Trust A Conceptual AnalysisDocument25 pagesWork Engagement and Its Relationship With State and Trait Trust A Conceptual AnalysisNely Noer SofwatiNo ratings yet

- Final Research ProposalDocument17 pagesFinal Research ProposalAsif NawazNo ratings yet

- The Relationship between Employee Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Counterproductive Work BehaviorDocument12 pagesThe Relationship between Employee Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Counterproductive Work BehaviorDaman WaruwuNo ratings yet

- Workplace Ostracism and Family Social Support A MoDocument41 pagesWorkplace Ostracism and Family Social Support A MoMariaIoanaTelecanNo ratings yet

- 05 Waseem FINAL PDFDocument12 pages05 Waseem FINAL PDFAmmara NawazNo ratings yet

- Job Involvement and Job Performance (Organizational Behavior)Document16 pagesJob Involvement and Job Performance (Organizational Behavior)Ahmed TarekNo ratings yet

- Effect of Workplace Incivility On OCB Through BurnoutDocument14 pagesEffect of Workplace Incivility On OCB Through BurnoutDuaa ZahraNo ratings yet

- SOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTFrom EverandSOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTNo ratings yet

- Relationship Leadership, Employee Engagement and Organizational Citizenship BehaviorDocument17 pagesRelationship Leadership, Employee Engagement and Organizational Citizenship BehaviorRudine Pak MulNo ratings yet

- Impact of Workplace Bullying in Employee Performance of Banking Sector of Nepal.Document14 pagesImpact of Workplace Bullying in Employee Performance of Banking Sector of Nepal.sujanNo ratings yet

- Demographic differences in work engagement Psihologija Nauka i PraktikaDocument15 pagesDemographic differences in work engagement Psihologija Nauka i PraktikatomovskaNo ratings yet

- Eatough Et Al (2011)Document14 pagesEatough Et Al (2011)azn1nfern0No ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Employee Engagement ADocument7 pagesFactors Affecting Employee Engagement AVijayibhave SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Work Stress On Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Modified Role of Emotional Intelligence (Centre For Lombok District Health Service Staff Study)Document6 pagesThe Influence of Work Stress On Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Modified Role of Emotional Intelligence (Centre For Lombok District Health Service Staff Study)International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Job Crafting We Ad WFCDocument11 pagesJob Crafting We Ad WFCShaffira WibowoNo ratings yet

- Stoeber Et Al Perfectionism and W in Employees - Motivation RoleDocument6 pagesStoeber Et Al Perfectionism and W in Employees - Motivation RoleVictoria DereckNo ratings yet

- 9360Document5 pages9360mamdouh mohamedNo ratings yet

- Hussein S ProposerDocument22 pagesHussein S ProposerHussein OlowuNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Work Engagement Behavior and Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational ClimateDocument11 pagesThe Relationship Between Work Engagement Behavior and Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational ClimateBakialetchumy TanasikaranNo ratings yet

- CWB 3Document21 pagesCWB 3Rebecca FrangklinNo ratings yet

- Role Stressors and Job Attitudes: A Mediated Model of Leader-Member ExchangeDocument18 pagesRole Stressors and Job Attitudes: A Mediated Model of Leader-Member Exchangerabiaw20No ratings yet

- 24 Hour Banking Deal or Dilemma - AIMS 2006 - IIM AhmadabadDocument7 pages24 Hour Banking Deal or Dilemma - AIMS 2006 - IIM AhmadabadVikram VenkateswaranNo ratings yet

- Journal of Business Research: A B B BDocument12 pagesJournal of Business Research: A B B BRanganadh PanchakarlaNo ratings yet

- IJMRES 6 Paper Vol 7 No1 2017Document14 pagesIJMRES 6 Paper Vol 7 No1 2017International Journal of Management Research and Emerging SciencesNo ratings yet

- Occupational Stress, Job Satisfaction, Mental Health, Adolescents, Depression and the Professionalisation of Social WorkFrom EverandOccupational Stress, Job Satisfaction, Mental Health, Adolescents, Depression and the Professionalisation of Social WorkNo ratings yet

- Ankur Final ReportDocument70 pagesAnkur Final ReportAnkur GoyatNo ratings yet

- Penney & Spector JOB 2005Document21 pagesPenney & Spector JOB 2005artha wibawaNo ratings yet

- Workplace Stressors in Private Sector Banks A Study of Women ExecutivesDocument17 pagesWorkplace Stressors in Private Sector Banks A Study of Women Executivesarcherselevators100% (1)

- Current Research in Social Psychology: Emotional and Behavioral Reactions To Work Overload: Self-Efficacy As A ModeratorDocument15 pagesCurrent Research in Social Psychology: Emotional and Behavioral Reactions To Work Overload: Self-Efficacy As A ModeratorKo Moe ZNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction of Executives in HyderabadDocument13 pagesJob Satisfaction of Executives in HyderabadHenry WaribuhNo ratings yet

- Penney & Spector JOB 2005Document20 pagesPenney & Spector JOB 2005Humera SattarNo ratings yet

- Effects of Workplace Incivility on Job Satisfaction and TrustDocument4 pagesEffects of Workplace Incivility on Job Satisfaction and TrustArin FerdianNo ratings yet

- Changes in The Frequency of Coworker Incivility - Roles of Work Hours, Workplace Sex Ratio, Supervisor Leadership Style, and IncivilityDocument13 pagesChanges in The Frequency of Coworker Incivility - Roles of Work Hours, Workplace Sex Ratio, Supervisor Leadership Style, and Incivilitytâm đỗ uyênNo ratings yet

- Future Directions Justice Types As Mediator, Jobe Level, Piccoli - 2017 - Scandinavian - Journal - of - PsychologyDocument11 pagesFuture Directions Justice Types As Mediator, Jobe Level, Piccoli - 2017 - Scandinavian - Journal - of - PsychologyMehr NawazNo ratings yet

- Job Attitude To Job Involvement - A Review of Indian EmployeesDocument9 pagesJob Attitude To Job Involvement - A Review of Indian EmployeesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- 1744-7941.12204Document26 pages1744-7941.12204Michelle PorterNo ratings yet

- 2. Commitment to Non Work Roles and Job Performance.enrichment and Conflict PerspectivesDocument11 pages2. Commitment to Non Work Roles and Job Performance.enrichment and Conflict Perspectivescharmaine.patocNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Workplace Incivility On Employee Absenteeism and Organization Commitment PDFDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Workplace Incivility On Employee Absenteeism and Organization Commitment PDFAqib ShabbirNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Workplace Ostracism, TMX, Task Interdependence, and Task Performance: A Moderated Mediation ModelDocument11 pagesThe Relationship Between Workplace Ostracism, TMX, Task Interdependence, and Task Performance: A Moderated Mediation ModelSubramani A.KNo ratings yet

- 10 3390@ijerph17030912Document12 pages10 3390@ijerph17030912Rieka Rahma WilyadantiNo ratings yet

- Assignment EngagementDocument9 pagesAssignment EngagementVidhi JoshiNo ratings yet

- Bakker, A.b., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A.I. (2014)Document4 pagesBakker, A.b., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A.I. (2014)L. BaptisteNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Deviant Workplace BehaviorDocument15 pagesDeterminants of Deviant Workplace Behaviorerfan441790No ratings yet

- The Impact of Ethical Leadership on Organizational CommitmentDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Ethical Leadership on Organizational CommitmentReyKarl CezarNo ratings yet

- A Study of Organizational Role Stress An PDFDocument8 pagesA Study of Organizational Role Stress An PDFPutri Celandine BremeniaNo ratings yet

- Understanding People at WorkDocument11 pagesUnderstanding People at Workapi-533953403No ratings yet

- Impact of Role Identity Salience Between Inter-Role Conflict, Domestic and Professional OutcomesDocument21 pagesImpact of Role Identity Salience Between Inter-Role Conflict, Domestic and Professional OutcomesDr. Sahira ZamanNo ratings yet

- Incivility EditedDocument7 pagesIncivility EditedDalmas SuarezNo ratings yet

- 2004 Colbert Et Al JAPDocument11 pages2004 Colbert Et Al JAPdanstane11No ratings yet

- Factors intrinsic to motivationDocument38 pagesFactors intrinsic to motivationArvin Jay AgillonNo ratings yet

- 2013 The Impact of Psychological Capital On Job Burnout of Chinese Nurses - The Mediator Role of Organizational CommitmentDocument8 pages2013 The Impact of Psychological Capital On Job Burnout of Chinese Nurses - The Mediator Role of Organizational CommitmentMary MonikaNo ratings yet

- Zhan et al 2018Document25 pagesZhan et al 2018Michelle PorterNo ratings yet

- Performance Management SystemDocument17 pagesPerformance Management SystemShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Research Variables DefinitionsDocument75 pagesResearch Variables DefinitionsShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts Organizational Composition & Role of HRM Management, Managers and OrganizationDocument12 pagesBasic Concepts Organizational Composition & Role of HRM Management, Managers and OrganizationShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Ridha Rahim Research Methodology MSMS-2019: Basic and Applied Research, N.D)Document14 pagesRidha Rahim Research Methodology MSMS-2019: Basic and Applied Research, N.D)Shaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Perception & DMDocument15 pagesPerception & DMShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Exercises of Paraphrasing - 1Document3 pagesExercises of Paraphrasing - 1Shaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Perception & DMDocument15 pagesPerception & DMShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Compensation Management SystemDocument10 pagesCompensation Management SystemShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- RMM Lecture 30 Data Transformation ADocument26 pagesRMM Lecture 30 Data Transformation AShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Employee Relation ManagementDocument11 pagesEmployee Relation ManagementShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- RMM Lecture 31-32 Data PresentationDocument40 pagesRMM Lecture 31-32 Data PresentationShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- International Human Resource ManagementDocument4 pagesInternational Human Resource ManagementShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Research Methods: FieldworkDocument21 pagesResearch Methods: FieldworkShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Assignment No 4 of RMDocument12 pagesAssignment No 4 of RMShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Baron & Kenny PDFDocument10 pagesBaron & Kenny PDFBitter MoonNo ratings yet

- South West AssignDocument2 pagesSouth West AssignShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- AWS Seeks Engineer to Build Customer Billing SystemDocument3 pagesAWS Seeks Engineer to Build Customer Billing SystemShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document6 pagesAssignment 2Shaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Shifa Hospital Problem ID and SolutionsDocument12 pagesShifa Hospital Problem ID and SolutionsShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Why Job Satisfaction and Employee Engagement MatterDocument4 pagesWhy Job Satisfaction and Employee Engagement MatterShaheena Sana100% (1)

- Last AssignDocument2 pagesLast AssignShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- OBDocument2 pagesOBShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Shaheena Hafeez S19MSMS011 HR Communication Strategy of Zong Internal CommunicationDocument5 pagesShaheena Hafeez S19MSMS011 HR Communication Strategy of Zong Internal CommunicationShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Job Opportunity: Sui Northern GasDocument3 pagesJob Opportunity: Sui Northern GasShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Int PMS Final PaperDocument12 pagesInt PMS Final PaperShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Self EfficacyDocument80 pagesSelf EfficacyShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Job Stress On Employee Performance: Research PaperDocument21 pagesImpact of Job Stress On Employee Performance: Research PaperShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Wellbeing Meta AnalysisDocument16 pagesPsychological Wellbeing Meta AnalysisShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Job Opportunity: Sui Northern GasDocument3 pagesJob Opportunity: Sui Northern GasShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 AdministrationDocument552 pagesRed Hat Enterprise Linux 5 Administrationsalmi20008No ratings yet

- ABORTIONDocument6 pagesABORTIONMarice Abigail MarquezNo ratings yet

- IELTS Writing Task 2 PatternDocument18 pagesIELTS Writing Task 2 Patternfaisal abdaNo ratings yet

- Kom Course File New Format M V ReddyDocument44 pagesKom Course File New Format M V ReddyVenkateswar Reddy MallepallyNo ratings yet

- Fibromyalgia and Cognitive Behavioral TherapyDocument2 pagesFibromyalgia and Cognitive Behavioral TherapyАлексNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics and Governance CitizenshipDocument4 pagesPhilippine Politics and Governance CitizenshipJoeriel AgtasNo ratings yet

- CivicslessonDocument2 pagesCivicslessonapi-220292228No ratings yet

- Intern PresentationDocument33 pagesIntern PresentationFirzan0% (1)

- Measure Academic Progress with Key Performance IndicatorsDocument21 pagesMeasure Academic Progress with Key Performance IndicatorsAbraham EshetuNo ratings yet

- Hillsdale Collegian 3.27Document12 pagesHillsdale Collegian 3.27HillsdaleCollegianNo ratings yet

- The System of Education in PakistanDocument43 pagesThe System of Education in Pakistanshaaz1209100% (1)

- Report On Performance Management System at InfosysDocument12 pagesReport On Performance Management System at InfosysDiksha Singla100% (2)

- Performance Appraisal Study at Wheels IndiaDocument14 pagesPerformance Appraisal Study at Wheels IndiaKalidoss DossNo ratings yet

- Cover PageDocument8 pagesCover PageAnonymous BAWtBNm100% (1)

- DLL Mathematics-6 Q3 W3Document10 pagesDLL Mathematics-6 Q3 W3Santa Yzabel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Capizzi's Supposed Proposals For Lincoln School Are LackingDocument136 pagesCapizzi's Supposed Proposals For Lincoln School Are LackingRC100% (1)

- What Is Debate?Document3 pagesWhat Is Debate?Bhavesh KhillareNo ratings yet

- Character Building FrameworkDocument6 pagesCharacter Building FrameworkfaradayzzzNo ratings yet

- Talent MGMT at NTPCDocument21 pagesTalent MGMT at NTPCfriendbce100% (1)

- NSTP SyllabusDocument1 pageNSTP SyllabusfrancisNo ratings yet

- Grade 12 - Class Program 2023-2024Document2 pagesGrade 12 - Class Program 2023-2024Rovelyn ClementeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ikram Ramadhan ValDocument7 pagesJurnal Ikram Ramadhan ValTeuku Muhammad ShandoyaNo ratings yet

- QUALIFICATION FILE - Embedded System Design Using 8-Bit: MicrocontrollersDocument3 pagesQUALIFICATION FILE - Embedded System Design Using 8-Bit: MicrocontrollersTarigAlmehmadiNo ratings yet

- Lesson Script For Teachers Math 9 Quarter 2-Week-4-TutorialDocument4 pagesLesson Script For Teachers Math 9 Quarter 2-Week-4-TutorialRichel PizonNo ratings yet

- Gynaecological Surgery D BissonDocument36 pagesGynaecological Surgery D BissondrdeegeeNo ratings yet

- Eng4 Q4 Mod1 Writing A Short Story v4Document20 pagesEng4 Q4 Mod1 Writing A Short Story v4Eugel GaredoNo ratings yet

- Organizational CultureDocument19 pagesOrganizational CultureNaya Cartabio de CastroNo ratings yet

- Action Research Title:: Improving Female Class Participation in 1 Year Section 1 Computer Science StudentsDocument4 pagesAction Research Title:: Improving Female Class Participation in 1 Year Section 1 Computer Science Studentsmehari kirosNo ratings yet

- Final Educ 8Document40 pagesFinal Educ 8Ive EspiaNo ratings yet

- Alumni Induction Ceremony Scripts: This Packet Contains Three Scripts For The Intended Uses ShownDocument22 pagesAlumni Induction Ceremony Scripts: This Packet Contains Three Scripts For The Intended Uses Shownapi-26283715No ratings yet