Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arestis Finance and Development Institutional and Policy Alternatives To Financial Liberalization PDF

Uploaded by

Ana GuevaraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arestis Finance and Development Institutional and Policy Alternatives To Financial Liberalization PDF

Uploaded by

Ana GuevaraCopyright:

Available Formats

Finance and Development: Institutional and Policy Alternatives to Financial Liberalization

Theory

Author(s): Philip Arestis, Machiko Nissanke and Howard Stein

Source: Eastern Economic Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Spring, 2005), pp. 245-263

Published by: Palgrave Macmillan Journals

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40315489 .

Accessed: 09/01/2014 11:37

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Palgrave Macmillan Journals is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Eastern

Economic Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FINANCE AND DEVELOPMENT:

INSTITUTIONAL AND POLICY ALTERNATIVES TO

FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION THEORY

Philip Arestis

ofCambridge

University

MachikoNissanke

ofLondon

University

and

HowardStein

ofMichigan

University

INTRODUCTION

On August7, 2002,Brazilreceiveda $30 billiondollarpackagethatwas thelarg-

estloangrantedinInternational Monetary Fund(IMF) history andbrought totalIMF

lending to the countryto $63 billion since 1998. The bailout was simply the latest

chapter in a recent of

saga unprecedented financial instability and crisisaffecting

virtuallyeveryregionoftheglobaleconomymercilessly. Since 1997therehave also

beenmajorcrisesinArgentina, Ecuador,Thailand,Russia,Uruguay,Columbia,Indo-

nesia, Kenya,and Korea. This instability has been associatedwithrapidfinancial

liberalizationwithoutexception.Forexample,in Korea,thecrisisofNovember1997

followed thederegulation ofinterestrates,theopeningofthecapitalmarket,foreign

exchangeliberalization,thegranting ofnewbankinglicenses,and thedismantling of

government monitoringmechanisms thatwere part ofthe policy loan system.

Thepost-1997patternofliberalization leadingtocrisisis a continuation ofearlier

trendsthathave becomeubiquitous in Latin America and elsewhere. In 1989,Ven-

ezuela implemented financialliberalizationas partofa standardorthodox IMF and

WorldBankadjustment package and sectoral loan. Policiesrelated tofinance included

the removalofquotas forpriority lending, the liberalization of interestrates,the

openingup ofthebankingsectorto foreign ownership, and the privatizationofcom-

mercialbanks.By 1994,thebankingsystemwas in a full-fledged meltdown. Between

January 1994 and August 1995, 17 financial institutions failed,encompassing 60 per-

centofthetotalassets ofthefinancialsystemand 50 percentofthedepositsand an

Philip Arestis: CambridgeCentreforEconomicand Public Policy,Departmentof Land Economy,

ofCambridge,19 SilverStreet,CambridgeCB3 9EP, UK. E-mail:pa267@cam.ac.uk.

University

EasternEconomicJournal,Vol.31,No. 2, Spring2005

245

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

246 EASTERNECONOMICJOURNAL

estimated20 percentoftheGDP tocleanup [Vera2002].In Mexico,liberalization and

privatizationintheearly1990shas provenalso tobe enormously costly.By 1999,the

costofthegovernment intervention reached$65 billionorroughly17 percentofthe

1998GDP [FinancialTimes1999]. Othercountries in differentregions,including the

CaribbeanandAfrica, havefollowed orthodoxcourses of financial with

liberalization,

verysimilarresults(see, forexample,Stein,Ajakaiye,and Lewis [2002]and Stein,

Cuesta,and McLennon[2002],fora numberofindividualcases in theseregions).

These examplesare notisolatedexceptionsbut morethe rule.Demirguc-Kunt

and Detragiache[1999] surveybankingcrisesin 53 countriescoveringthe period

between1980and 1995and findthat78 percentofall criseswerelinkedtoperiodsof

financialliberalization(see also WorldBank [2001,83] Table 2.1 fora comprehensive

listofthecostsinvolvedin theseand othercrises,amounting to 50 percentofGDP in

somecases). Giventheubiquityofthesecrises,whydo governments pursuefinancial

Answerstothisquestionincludetheinstitutionalization

liberalization? inrecentdecades

ofnormsof"acceptable"financialpolicies,theperceivedpotentialgainsofattracting

privatecapitalinflows, thenatureofglobalsystemsand theasymmetric powerrela-

tionsembeddedinglobalstructures thatdelimitnation-state options,and,finally,the

expectedgains arisingfromthe economiclogicembeddedin the theoryunderlying

financialliberalization.

Thispaperwillfocuson thelatterquestion,arguingthatfinancialliberalization

policyis builton shakytheoreticalpremises.We suggestthatthe recentfinancial

crisesthat have hit so manydevelopingcountriesand transitionaleconomiesare

inducednotmerelybytheinappropriate sequencing,pacing,ortimingofinternaland

externalfinancialliberalization, buttheyare theinevitableoutcomeofadoptingthe

policythatis based on a veryshallowunderstanding ofthe dynamicrelationships

betweenfinanceand economicdevelopment. In ourview,financialtransformation in

the imageofMcKinnon-Shaw has engenderedwidespreadbankingcrisesprecisely

becauseoftheweakfoundations ofthetheory.Ourviewis thatbad theorygivesrise

topoliciesthatgiveriseto crises.In contrast, theproponents ofthefinancialliberal-

izationthesissee financialcrisesas somehowirrelevant totheirtheoryand thepolicy

thatit has inspired.This is paradoxicalin thatproponents argue,whencrisestake

place,that more oftheir policyprescriptions should thecure,whenit is precisely

be

thosepoliciesthatcausedthecrisesinthefirstinstance.Polanyi[1957]describesthis

paradoxverywellwhenhe arguesthattheapologists, thedefenders offinancialmar-

ketliberalization,"arerepeatingin endlessvariationsthatbutforthepoliciesadvo-

catedbyits critics,liberalismwouldhave deliveredthegoods;thatnotthecompeti-

tivesystemand the self-regulating market,but interference withthatsystemand

interventions withthatmarketare responsible forourills"(p. 143).Hence,thepaper

aims at sketchingan alternativetheoreticalperspective byexamininginstitutional

for

requirements buildingand transforming financialsystemsforeconomicdevelop-

ment.The focusis howto enhancetheoperationaland developmental roleofbanks

and otherfinancialentitieswithinthebroaderfinancialsystem.The aim is totrans-

form themeso-level, whichmediatesmicroandmacrofinancial relationsinan economy.

We are notlookingspecifically at themicrolevel,butat factorsthataffect themicro

dimensions.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TO FINANCIALLIBERALIZATION

ALTERNATIVES THEORY 247

The paper is structuredas follows:We firstgive a briefpresentationofmain

thesesin financialliberalizationtheory(section2). Thisis followedbya critiquefrom

boththeoretical(sections 3 and 4) and empirical(section5) pointsofview.Section6

offersan alternativeperspectiveon financialtransformation moreconsistentwith

economicdevelopment (thatis, consistentwithbothan institutionalist theoryofeco-

nomicdevelopment and withtherealityoftheinstitutional structureofdeveloping

economies)thatdrawson a ratherdifferent setoftheoretical toolsand ideas. Finally,

section7 summarizesand concludes.

FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION THEORY: RETURNING TO THE ORIGINAL

TEXTS

Financialliberalizationtheory has itsoriginsintheworkofMcKinnon[1973]and

Shaw [1973].It was Patrick[1966],however, whopublishedtheseminalworkonthe

relationshipbetweenfinancialdevelopment and economicgrowth.He hypothesized

twopossiblerelationships, a "demand-following" approach,inwhichfinancialdevelop-

mentarisesas theeconomydevelops,and a "supply-leading" phenomenon, in which

thewidespreadexpansionoffinancialinstitutions leads toeconomicgrowth. Priorto

Patrick[1966]therehad been a greatdeal ofdebateon theissue,withcontributors

ranging fromBagehot[1873]andSchumpeter [1912],whosupported thesupply-leading

view, toRobinson [1952],who voicedstrongsupport for thedemand-following approach,

tomention onlythemainprotagonists. Thefinancial liberalization

schoolleanstowards

thesupply-leading relationship betweengrowthand development [McKinnon, 1973].

Theargument arisesoutofa highlysimplified worldwithoutfinancialintermediaries,

wherebythe purchaseofcapitalcan onlyarise fromself-finance; forwhenan indi-

vidualwhois limitedtoself-finance wishesto"purchasephysicalcapitalofa typethat

is differentfromhis own output...He may storeinventoriesofhis own outputfor

eventualsale whenthecapitalassetsare acquiredorhe maysteadilyaccumulatecash

balancesforthesamepurpose"McKinnon,1973,57].

In theirview,priorsavingsare seen to help the accumulationprocess.Conse-

quently,accordingto thisview,thekeyis to altertheincentivesbetweenconsump-

tionand saving.Followingclassicaleconomics, interestrates are seen as providing

thereturnforthischoice.1 Wheninterestratesarekeptartificially low,theresultwill

For

be shallowfinancing. example, Shaw [1973,8] argues:"Deepeningimpliesthat

interestratesmustreportmoreaccuratelytheopportunities thatexistforsubstitu-

tionofinvestment forcurrentconsumption and the disinclination ofconsumersto

wait. Real rates ofinterestare highwherefinanceis deepening."UnlikeKeynes

[1936],inwhichinterest ratesaffectthedemandforand supplyofmoney, Shaw [1973]

followstheclassicalmodel,inwhichtheequilibrium betweensavingsand investment

is determined by interestrates. A rise in real interestrates increasesthe flowof

savingsand reducestheexcessdemand.Ratesofreturnonholdingmoneyalso playa

rolein increasinginvestment levels[McKinnon, 1973].

In thisparadigm,thedesiretoholdmoneyis also positively affectedbytherateof

returnon capital,contrary to theportfolio approach(whichhas a negativerelation-

ship).Withhigherinvestment, therewillalso be a relatedimprovement inthequality

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

248 EASTERNECONOMICJOURNAL

ofinvestment and a riseinthesavingslevelsallocatedthrough themarket.Rationing

ofcreditreducesthequalityofintermediation, however, withnegativeconsequences

to investment: "Rationingis expensiveto administer.It is vulnerableto corruption

andconspiracy individing betweenborrowers andofficers oftheintermediary monopoly

rentthatarisesfromthedifference betweenlow,regulatedloanrateand themarket-

clearingrate.Borrowers whosimplydo notrepayloans and keep theirplace in the

rationqueuebyextending maturitiescan frustrate it.Therationing processdiscrimi-

nates poorlyamonginvestment and

opportunities... the social cost of thismisalloca-

tionis suggestedbythehighincremental ratiosofinvestment tooutputthatlagging

economiesreport"[Shaw,1973,86].

It is further arguedthatcompetition throughprivateownershipcan shrinkthe

difference betweendepositandloanrates,encouraging "optimal" agreements between

banks,and amongborrowers andlenders,inturnincreasingtheefficiency ofinterme-

diation.Moreover, "fragmentation" indeveloping countries: "...inthesensethatfirms

and householdsface...different effective

prices for land, labor, capitaland produced

commodities. ..hasbeenlargelytheresultofgovernment policy"[McKinnon, 1973,5-7].

Reversing fragmentation bycreatinga singlecapitalmarketthrough theretractionof

state intervention is thenregardedas the sine qua non ofeconomicdevelopment:

"Arbitrary measuresto introducemoderntechnology via tariffs,or to increasethe

rateofcapitalaccumulation on

byrelying foreign aid or domestic forced saving,will

notnecessarily lead toeconomic development. Thusitis hypothesized thatunification

ofthecapitalmarket,whichsharplyincreasesratesofreturnto domesticsaversby

widening exploitable investmentopportunities,is essentialforeliminating otherforms

offragmentation" [McKinnon, 1973,9].2Byimplication, McKinnon [1973]and Shaw

[1973]supporttheliberalizationofthecapitalaccountin orderto providea unified

capital market forprivate decision makers to undertake utility-maximizing

intertemporal choice.3

A THEORETICAL COMMENT ON THE FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION

HYPOTHESIS

Thereare severalfundamental problems withthefinancialliberalizationhypoth-

esis. To beginwith,theargumentis developedin an almostRobinsonCrusoeframe-

work,in whichall investment is self-financing.Thisis abstractedfromthecomplexi-

tiesofmoneyas a socialinstitution. In reality,moneyis bynaturesociallyembedded.

Theholdingofmoneyevenin thesimpleruralsettingdiscussedbyMcKinnon[1973],

is subjectto socialobligationsand constraints, and notsimplydrivenbyinvestment

needs,theproductivity ofcapital,and real returnon holdingmoney.Moreover, the

is It

presentation contradictory. justis not possible totalkabout self-financing no

as if

otherfinancialoptionsexist,and discussa returntoholdingmoneyas some"weighted

averageofnominalinterestratesofall formsofdeposits"[McKinnon, 1973,39],which

presupposestheexistenceofa sophisticated financialsystem.

McKinnon[1973]is, ofcourse,determined to showa positiverelationshipamong

higherinterestrates,financialdevelopment, and investment and growth.He is criti-

cal oftheneoclassicalportfolio approach,inwhichindividualschoosebetweenmoney

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TO FINANCIALLIBERALIZATION

ALTERNATIVES THEORY 249

and assets,sinceit positsa negativerelationship betweenthe demandforreal bal-

ancesand thereturnonnonfinancial assets.He reallyis notescapingfroma portfolio

approach,however;he simplyredefines it as a choicebetweena noninterest-bearing

asset(own stocks of products) money(whichis interestbearing).Byintroducing

and a

laggedtimedimensionintothe choicebetweenmoneybalances and nonmonetary

assets,holdingtheportfolio as a storeofvaluebecomesthefocalpointinhis analysis.

The totalofthisportfolio is relatedto thedesiredrate offuturecapitalinvestment.

Thehighertheexpectedrateofreturn, thegreaterthedesiretoholdmoneybalances.

McKinnon[1973]wouldarguethat,inproperly operatingcapitalmarketswithout

fragmentation, all that is necessary is a single unifying marginal rate ofreturn.

Economy-wide choices then simplyoperate like individual choices.The problemwith

thisperception is thatcapitalmarketshave neveroperatedin thismanner.Markets

are alwaysfragmented and repletewithdifferent levelsofriskand uncertainty even

in the mostadvancedeconomies.Perceptionsofrates ofreturnvarynotonlywith

differenttypesoffinancialvehiclesbutalso byindividuals. Anindividualona particu-

lar projectperceivesinterestrates paid by governments verydifferently fromthe

anticipated futurereturn.Nothingwillautomatically unifythemintoa singleconcat-

enatingvisionofa futurepayout.

Thetheoryoffinancialliberalization also reliesontheassumptionofthecompeti-

tivemodel.The divergence betweenthefinancialworldand thecompetitive modelis

profound, however.Financeis repletewithasymmetries ofriskand information that

are less evidentin goodsmarkets.Stiglitz[1989,1994] pointsto a hostofmarket

imperfections embeddedinfinancialmarketsthatgobeyondthewell-known issuesof

moralhazard and adverseselection.Theyinclude:1) the largedivergence between

thesocialand privatecostsofbankfailures;2) thepublicgoodnatureofthesolvency

ofinstitutions that are likelyto be undersupplied;3) the externality effectofthe

presenceofa fewbad banks on the confidence of the sector;and 4) the divergence

betweentheprivate(thosewithrapidturnover) and social(projectsare likelytohave

longerturnover periodsandhigherrisk)benefits ofloans.Furthermore, and contrary

tothestandardassumptionofmarkets,financialmarketswillnotbe Paretoefficient

(wherethepricerepresents themarginalbenefit tothebuyerand themarginalcostto

thesupplier),sincetheborrower (buyer)willingto pay themostfora loan,maynot

the

provide highestprofit to the lender (seller).An important recentcontribution by

theimperfect information schoolgoes to theheartoffinancialliberalizationthesis,

thatis,theenhanceddegreeofcompetition itcreates[Hellman,Murdock, and Stiglitz,

2000].Morecompetition, according tothiscontribution, erodesfranchise value,which

reducesincentivesforprudentialbehavior,therebysubstantially increasingriskin

thesystem.The problemoffinancein developing countriesis muchdeeperand more

multifaceted, however, thansuggestedbytheimperfect information school,as argued

below.

Thefocalpointoffinancialliberalization is onretracting thesourcesofrepression

thathavedistorted thesignalingeffect ofinterestrates.Eitherthesignalsthemselves

are disruptedbythe"fragmentation" createdbygovernment policyorthesignalsare

misreaddue to thestateownershippatternoffinancialorganizations. On thelatter

point,it is an axiomaticbeliefthatthe publicownershipor controlalwaysleads to

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

250 EASTERNECONOMICJOURNAL

politicalorpatronageinfluences, whileprivateownerswillreactto thesignalswith

Paretoefficient decisionson the allocationofcredit.Stiglitz[1989,1994],and the

imperfect informationschool,recognize thatfinancialmarketslefttotheirowndevices

aregenerally of

incapable providing correctsignals.Stateintervention shouldbe aimed

at creatingmoderateformsoffinancialrepression to alterthe signalsthatlead to

moresociallyoptimaloutcomes. Theproblem is that,giventhepoorlydevelopednature

offinancialmarketsin developingcountries, evenadjustedsignalingmaynothave

thedesiredresultsand mayevenlead tounintendedconsequences.In countrieslike

Nigeria- whereregulationis poor,normsoftrustare notdeveloped,and a military

government handsoutbankinglicensestomilitary officials- subsidizing interestrates

wouldhave donelittleto reversethe financialchaos createdbyliberalizationafter

1986.Whileinterestratesare important, theyare onlyone dimensionoftheincen-

tivesanddisincentives thatinfluence thedecision-making processinfinancial systems.

The McKinnon-Shaw worldoffinanceis one wherefinancialintermediaries via

marketsfordepositing andlendingsimplysetinterestratestobalancethesupplyand

demandforsavingsofborrowers and depositors. In thisworld,thereare threeactors

in twoexchangeswiththedifference in thepriceofthetwoexchangessimplyreflect-

ingthecostofintermediation (whichwillbe keptlowwithsufficient competition). One

only needs the unfettered of

operation self-seeking atomistic individuals to arriveat

Paretooptimality. Thereis noneedforinstitutions. However, in the real world,inter-

estratesandincentivesare onlyonedimensionoffinance, whichis a complexinstitu-

tionembeddedin a broadersystemofnonfinancial institutions. As we willsee below,

many of the econometric studies have difficultypinpointing clear causalitybetween

financeand development. We wouldarguethisis preciselybecauseoftheintertwin-

ingand interaction betweenthedevelopment offinancialinstitutions andthefinance

ofdeveloping institutions.

Theseissueswillbe exploredbelow.

Financialtransformation in theimageofMcKinnon-Shaw has engendered wide-

spreadbanking crisespreciselybecause ofthe weak foundations ofthe theory.How-

ever,McKinnon[1993]has arguedthatit is not a problemwiththe theoryor the

policiesarisingfromthetheory, butone ofsequencing,particularly whenderegula-

tionis introducedbeforemacroeconomic stabilization is completed. Weturnouratten-

tionnextto thisissue.

SEQUENCING, MACROSTABILITY, AND POLITICAL ECONOMY

McKinnon[1993]attemptedto accountforinstitutional capabilitiesand weak-

nesses under"theoptimumorderofeconomicliberalisation." He arguesthat"How

fiscal,monetary, andforeignexchangepoliciesaresequencedis ofcriticalimportance.

Government cannot,and perhapsshouldnot,undertakeall liberalizing measuressi-

multaneously. Instead,thereis an order

'optimal' of economicliberalisation, which

mayvaryfordifferent liberalizingeconomiesdependingon theirinitialconditions"

[McKinnon' 1993,4] Thisoptimalorderwouldbeginwiththecontrol ofinflation, lead-

ingtothe deregulationofinterest and

rates,bankingprivatization commercialization,

foreign exchangerateunification, tradeliberalization,

and onlythenopeningup the

capitalaccount.Caprio,Atiyas,andHanson[1994]reviewfinancialreforms in a num-

berofprimarily developingcountrieswiththeexperienceofsix countriesstudiedat

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALTERNATIVES

TO FINANCIALLIBERALIZATION

THEORY 251

somedepthand length.Theyconcludethatmanagingthereform processratherthan

adoptinga laissez-faire stanceis important, andthatsequencingalongwiththeinitial

conditions infinanceandmacroeconomic stability are criticalelementsinimplement-

ingsuccessfully financial reforms. It is thusrecommended nowthatgradualfinancial

liberalizationis to be preferred. In thisgradualprocess,a "sequencingoffinancial

liberalization" is recommended, emphasizing theachievement ofstabilityinthebroader

macroeconomic environment and adequatebanksupervision withinwhichfinancial

reforms are to be undertaken[Choand Khatkhate,1989a; McKinnon,1988; Sachs,

1988;VillanuevaandMirakhor, 1990]. Employing credibilityarguments, Calvo[1988]

and Rodrik[1987]suggesta narrowfocusofreforms withfinancialliberalization left

as last.

The argumentembeddedin theorderoffinancialliberalization has increasingly

beenchallenged. A morerecentliterature has indicatedthatfinancialliberalization in

has

anysequence engendered the same Even

difficulties. where the "correct"sequencing

tookplace (forexample,Chile),wheretradeliberalizationhad takenplace before

financialliberalization, not muchsuccesscan be reported.It is also truein those

cases,likeUruguay,wherethe"reverse"sequencingtookplace- financialliberaliza-

tionbeforetradeliberalization - thatthe experiencewas verymuchthe same as in

Chile.The experience with financial liberalization, in bothdevelopedand developing

countries, in the 1980s and 1990s suggestsa markedincreasein thefrequency and

severity of financial crisesirrespective ofthe order of sequencing [Lindgreen, Garcia,

and Saal, 1996; Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache,1998; Grabel,1995; Arestisand

Demetriades, 1997].

Moreover,the studyby Weller[2001]surveys26 countriesrepresenting every

region ofthe world to evaluate the relationship between financial liberalizationand

crisis.Amongthesampleare manyvariationsin thesequencingofpolicies.Drawing

ontheworkofMinsky[1984], a numberofhypotheses abouttherelationship between

financial liberalization andthebankingcrisesthattypically followaretested.Internal

and externalderegulation fostersfinancialfragility byencouraging flowsto specula-

tiveventures.Assetinflationcan raise the collateralofborrowers and increasethe

euphoria.Speculationbecomesself-fulfilling as greaterflowsintospeculationin turn

perpetuatethespeculativeboom.Short-term capitalinflowsafterliberalization can

raisetheexchangeratesleadingtodeterioration inthecurrentaccount,withimplica-

tionsto real growthin sectorslike industry.This is exacerbatedby the shiftaway

from investment finance tospeculation. Eventually, assetpricesbegintodeflate, default

riskrises,and maturity riskincreasesas short-term outflows increasein responseto

theworsening balancesheetofbanks.Ultimately, theeconomy is markedbya risein

interest rates, credit contraction,import and

priceinflation, depleteddomestic demand.

Weller's[2001]resultsconfirm thesehypotheses, especiallythatofthegrowthof

financialfragility afterfinancialliberalization.Indeed,morespeculativefinancing

greatlyenhancesthechancesofa bankingcrisisafterfinancialliberalization. Ofpar-

ticularinterest is howlongfinancial liberalization willcontinue toincreasethechances

offuturefinancialcrises.It has beenfrequently arguedthatfinancialliberalization

mightlead to short-term dislocationbut it will be beneficialin the longterm.The

resultsindicatethatthelikelihoodofa bankingcrisisdoes notdisappear,however,

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

252 EASTERNECONOMICJOURNAL

butit in factincreasesovertime.The studybyArestisand Glickman[2002]reaches

similarconclusions inthecaseoftheSouthEastAsiancrisis,supporting thesehypotheses.

Otherstudieshavealso confirmed thelackofsignificance of"sequencing." Arestis,

Demetriades, and Fattouh [2003]survey theliteratureand offertheir own empirical

investigation, and findno evidencethatvaryingthesequenceoffinancialliberaliza-

tionalongMcKinnon's[1993]optimallinesleads toanydifferent results.In linewith

Weller's[2001]findings, thereis strongevidenceofincreasingfrequency and severity

offinancialcrisesinthewakeofliberalization. A WorldBankeconometric studyofthe

relationship betweenbankingcrisesand a seriesofexplanatory factors [Demirguc-

Kuntand Detragiache,1999],foundthemtobe highlycorrelated withfinancialliber-

alizationpoliciesevenwhencontrolling forfactorslikethesequencingrecommended

by McKinnon [1993]. Other problems with "sequencing"includethe questionofits

timing, thatis, howdo policymakersknowwhenit is timetomovefromone stageto

thenext?Sequencing,ofcourse,can easilycreateinertiain reform, ifindeedreform

is necessary.

The notionoftheexistenceofsomeoptimalsequencecan be questionedforother

reasons.Anyevaluationoffinancialliberalization shouldnotbe merelybased oneco-

nomiccriteria,but shouldalso containelementsfromthe realmofpolitics(Armijo,

1999).Thereis also theratherflawedbeliefthatorthodox financialliberalization will

lead toan improvement thatis growth enhancing. Underhill [1997], contrast, far

in is

less sanguineconcerning theprospectofeconomicgainsfromfollowing someoptimal

sequenceoffinancial transformation. Bynature,anychangeinexisting financialarrange-

mentscreatesnew winnersand loserswithimplications to the politicalrealm.He

characterizes thenewchangesin a financialsystemas constituting desegmentation

(unifying variousbranchesoffinanceintoa singlebranch),marketization (domestic

financialmarketliberalization) and transnationalization(integrating financialmar-

ketsacrossnationalboundaries).The actualoutcomeofchangevariesin accordance

withthe relativestrengthofthe constituent membersofthe financialcommunity

(government players,including centralbankersandregulators, nationalandmultina-

tionalbanks,pressuresfrominternational financialinstitutions,

strength ofprivate

involvement in privatization, etc.).The finaloutcomeis unpredictable withno guar-

anteeofanyeconomicimprovements and involvesconsiderable downsideriskfollow-

inganysequence.

ExamplesofUnderhill's[1997]observation abound.In Nigeria,underthemilitary

rule ofBabingida,applicationsforall new bankinglicenseswerereviewedby the

President'sofficeand FederalExecutiveCouncilcontrolled bythemilitary.Retired

militaryofficials withnobankingexperience wereinstrumental inobtaining banking

licenseswithoutthe properproceduresbeingfollowed.Centralbank officials who

wereinterviewed indicatedthenearimpossibility ofturningdownapplicationsinthe

climateofmilitary control.It is hardtoconceiveofanysequenceofreform working in

thisclimateor changingtheresultsofthenowwell-documented bankingcrisisthat

followed.In addition,politicsplayeda majorrolein the attemptto reorganizethe

financialsystemafterthebankingcrisis.In Nigeria,after1996,GeneralAbachaused

theopportunity topunishpoliticalopponents and challengetheindependence ofsome

businessgroups[Lewisand Stein,2002].

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TO FINANCIALLIBERALIZATION

ALTERNATIVES THEORY 253

Finally,somehave suggestedthatMcKinnon[1993]was implicitly arguingfor

greaterprudenceandgradualisminfinancialreform. Based onourabovearguments,

however, thattheproblemis neithertimealonenorsequence,but

itis ourcontention

linkedto a fundamental misconceptualizationofthe underlying

theorybehindthe

financialliberalization oftheorder.

thesis,irrespective

EMPIRICAL STUDIES OF THE FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION

HYPOTHESIS

The importance ofexaminingthebroaderconditions beforetransforming finan-

cial systemsgoesbeyondtheframework ofpoliticaleconomy totheunderlying struc-

turesofany developingeconomy. While there is broad agreement on the complica-

tionsofundertaking liberalization inthemidstofmacroinstability, whereeconomies

are structurallyweak,subjectto thevicissitudesofinternational commodity prices

and shiftingfinancialflowswithfewstabilizingreserves,instability is likelytobe the

ruleratherthantheexception. Evenwhenbankersare completely honestandregula-

torysystemsare in place,macroinstability or thelikelihoodofa futureoccurrence

will encouragebankersto holdreservesin government paper and to limitloans to

short-term duration. In places like Venezuela,Nigeria, and Russia,financialliberal-

izationledtoa decreaseinthedurationofloansandincreaseintheholdingofgovern-

mentpaper [Stein,Ajakaiye,and Lewis,2002]. In Tanzania, althoughmostofthe

bankingsystemis nowin foreign privatehandsand inflation has fallenbelow5 per-

cent, banks are sitting on 60 percent excess reserves with much ofit beingheld in

government paper[TheAfrican, 2002].

Giventhecentralroleofthefinancialliberalization hypothesis in liberalization

programs and the evolvingliterature, there has been a proliferation ofeconometric

testingofthetheory and attendant policycorrectives. In general,despitecontinuing

effortstodiscernthepostulatedpositiverelationship betweenfinancialliberalization

andgrowth bymainstream economists through cross-country studies,4 supportforthe

financialliberalization hypothesis is not verystrong and there is growingevidence

confirming Keynes'[1936]viewofthelinkageamong interest rates,investment, and

savings.

We beginwiththeliteraturethatteststhefinance-to-development causationor

supply-leadingrelationship. Habibullah [1999] surveys the literature for the financial-

led growthhypothesis and undertakes his own testing,finding little evidence to sup-

portthis hypothesis.5 Akinboade[1998] also uses Grangercausalitytestingin a

cointegrationframework on Botswanadata coveringtheperiod1972to 1995,tofind

clearbi-directionalcausality.Similarly, Sahoo,Geethanjali,andKamaiah [2001]note

in

thatinthecase ofIndia the 1970s highlevelsofsavingsdidnotlead tohigherlevels

ofgrowth.Later periodsofgrowthseemedto occurwithoutan appreciablerise in

savings.To examinethis moresystematically, theyapplycausalitytestingofreal

savings and realGDP data from 1950/51 to 1998/99. Theymanagetoestablisha strong

one-waylinkage from to

growth savings and therebyrefutetheproposition thatsav-

ingswas theengineofgrowthin thecase ofIndia.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

254 EASTERNECONOMICJOURNAL

The growth-to-savings causalityhas also been confirmed bysomeWorldBank's

studies.Countriesin Asia wereverysuccessfulin mobilizing savings,yetstrongevi-

denceindicatesthatinvestment and growthled to savingsratherthan savingsto

growth. It was notsavings thatled tothephenomenal investment and growth ratesof

recentdecades,buttheriseofincomethatincreasedsavings.The WorldBank [1993]

foundthecausationfromgrowth tosavingsinfivecountries (Indonesia,Japan,Korea,

Thailand, and Taiwan) and ambiguity in two (HongKong and Malaysia);inoneitwas

due tootherfactors(in Singapore,thestateprovident fundwas salient).

Surveysoftheliteratureindicatelittleor no evidenceofa positiverelationship

betweeninterestratesand savings[Dornbuschand Reynoso,1993]. Variousecono-

metrictestingfromAsia, LatinAmerica,and Africaalso confirms thelack ofcorre-

spondence between interest and savings, even amongstrongproponents oforthodoxy

likeFry[1988]as wellas manyothers(forexample,Giovannini[1985],Gupta[1987],

Cho and Khatkhate[1989b], GonzalezArrieta[1988],De Melo and Tybout[1986],

WarmanandThirlwall[1994],Oshikoya[1992],Taiwo[1992],andReichel[1991]).The

overwhelming evidencehas evenencouraged McKinnon[1993]toabandonthehigher-

interest-to-prior-savings argument in favorofa risein the"quality" ofinvestment after

liberalization.

Worseforthefinancialliberalization thesis,thereare studiesthathave actually

showna negativerelationship between interest ratesand savings.Matsheka[1998]

teststherelationship betweenthevariablesfortheperiod1976to 1995in thecase of

Botswana.A negativeand significant relationship betweenrealdepositinterestrates

and thelogofrealdomesticsavingsis foundtoprevail.The samestudyalso examines

theeffect ofdepositrateson privatesavinglevels(sincesavingsare overwhelmingly

dominatedbythegovernment in themineraleconomyofBotswana)and stillfindsit

negativeand significant. Matsheka[1998]takesitonestepfurther and disaggregates

theimpactofrealinterestratesintothenominalportionandtheinflation component.

The financialliberalization schoolpredictsthatthenominalinterestratewillhave a

positiveimpactonprivatesavingsand theinflation ratea negativeimpact.Contrary

to theirprediction, the resultsare the opposite.The nominalrate is negativeand

significant and the inflationrate positiveand significant. This is consistentwitha

Keynesian-type precautionary motiveofsavingsratherthana monetarist-type portfo-

lio shiftfromsavingsto assetsthatare inflation hedges.

Studiesutilizingdata on real interestratesand financialsavingshave produced

moremixedresults,eventhoughtheyare consistent withbothKeynesianand finan-

cial liberalization theory.Warmanand Thirlwall[1994]showa strongcorrelation be-

tweenrealinterestratesand M4,netofdemanddepositsintheMexicancontext. Seek

and Yasim [1993]indicatea correlation betweenM2/GDPand real depositinterest

ratesfora pooledsampleof21 countries withinAfrica(and also fora subgroupofnine

ofthe countriesthatincludesBotswana).This is usinga simpleregressionwithan

absurdlylow adjustedR2(.084), however.Moreover,Matsheka [1998]is unable to

confirm theseresultsforBotswana.Therealdepositrateis negativeandinsignificant.

Further, literaturetestingtherelationship betweenrealinterest ratesand invest-

mentseldomconfirms therelationship predictedbyMcKinnonand Shaw. Warman

and Thirlwall[1994]use Mexicandata and findan overallnegativerelationship. In a

sample of nine Africancountries, Seek and Yasim [1993]find a positiverelationship

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALTERNATIVES

TO FINANCIALLIBERALIZATION

THEORY 255

betweenreal depositratesand investment ratesin a simpleregressionwithridicu-

louslylow adjustedR2(0.039). Oncetheeffect is brokendownintonominalinterest

ratesand inflation and othervariablesare introduced, however,therelationship no

longer holds. Nominal interest rates have a and

negative significant relationship with

investment. In thecase ofBotswana,Matsheka[1998]showsa negativebutinsignifi-

cantrelationship betweenrealdepositratesand thelogofgrossdomesticinvestment.

the

Bycontrast, availability ofcreditand a laggedaccelerator relationshiparepositive

and significant. As theauthorpointsout,credithas actuallybecomeless availableto

theprivatesectorin thewake offinancialliberalization, a phenomenon also seen in

Nigeria and in Jamaica. In the case of Jamaica, for real to

example, lending manufac-

83

turingplummeted percent between 1989, when financialliberalizationbegan,and

1999 [Stein,Cuesta,andMcLennon2002].Similarly, inNigeria,therewas a negative

andverysignificant relationship betweenthenumberofbanksandreallendingtothe

privatesectorand thenumberofbanksand theleveloffinancialsavingsrelativeto

GDP. Financialdisintermediation and a viciouscirclearosefromliberalization, not

thevirtuouscirclepredicted byMcKinnon-Shaw [Lewisand Stein,2002].

Othersurveyshave indicatednegativeconsequencesoffinancialliberalization.

Ndung*u [1997]surveysnineEnglish-speaking African countriesintroducing orthodox

financialliberalization and findsdeclininginvestment; fewexamplesofa risein sav-

ings;reducedefficiency ofintermediation, as measuredbytherisingspreadbetween

depositand lendingrates;and fallingGDP growthrates.Otherauthorshave docu-

mentedrisinginterestratespreadsinplaceslikeVenezuela[Vera,2002]and a mixof

African countries[Nissanke,2002].ForJamaica,Stein,Cuesta,andMcLennon[2002]

testtherelationship betweenthegrowth offinancial institutions

andthespreadbetween

deposit and lending rates,and establish a positive and significant

relationshipbetween

thenumberoffinancialinstitutions andthespread,completely contraryto the predic-

tionofMcKinnon-Shaw. The chaoscausedbyfinancialliberalization was leadingto

growing inefficiencyofintermediation.

It followsfromthe aboveanalysisand empiricalresultsthatit is paramountto

developalternativesto the McKinnon-Shaw thesis,givenits weak theoreticalbase

andpoorempiricalperformance. Forthis,we proposetoadoptan institutional-centric

viewoffinance anddevelopment as a waytowards alternativefinancial formulation.

policy

FINANCIAL SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT: TOWARD AN INSTITUTIONAL

PERSPECTIVE

Our analysisso farclearlyindicatesthat the focuson priceformation largely

rendersfinancialliberalization italso lendsitselftomisunder-

theorya-institutional;

standinghowinstitutions in developingcountries

work,whenscantattention is paid

tothem.Yet,thecriticalimportanceof"institutional

endowments" foreconomic growth

beenemphasized

has increasingly bymanyrecenteconometric - see,forexample,

studies

Rodrik[1999]and Acemogluet al. [2002]fortheinstitutions-growth-macroeconomic

performances,and Chinnand Ito [2002]forthe institutions-financial development

link.Even authorslargelyin favorofthegoal ofmonetary restrainthave recognized

theimportanceofdesigning newpoliciesinthecontextofthe"institutional

endowments"

ofcountries[Ball, 1999].The performance ofnew institutional arrangements, like

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

256 EASTERNECONOMICJOURNAL

independent centralbanks,dependsonthecountry's otherformalarrangements, such

as fiscalpolicy,and manyinformal institutional arrangements, likedomesticinterest

grouporganizations; international relations;andthehistory, norms,andideology ofa

country. What is useful from Ball's [1999]analysis is the recognition that financial

transformation is fundamentally an institutional phenomenon, whichinteractswith

theexistinginstitutional endowment. Whatis less usefulis thedichotomous distinc-

tionbetweenformaland informal institutions. Theformal-informal distinction arises

fromtheworkofNorth[1990]and is aimedat explainingthehiddenconstraints on

formallevelsoftransformation. In the case ofBall [1999]thesehiddenconstraints

affecttheextentoftherigidity neededin newmonetary institutions in creatingrules

formonetary constraint. The greateris the informal commitment to monetary con-

the

straint, greater is the in

flexibility usingmonetary in

policy reacting to unfore-

seen shocks.

Thereare problemswithBall's [1999]framework. First,thedistinction between

formaland informal is ratherarbitrary. As Sindzingreand Stein [2002]note,differ-

encesbetweenthe formaland informalconstitutea continuumofactivitiesrather

thana dualityofpolaropposites.Second,theformal/informal distinction is usedinthe

sense ofmaximizing an objectivefunction subjectto constraints. The relationship is

unidirectional in thesensethattheinformal acts to limittheformalin reachingthe

goal or objectivefunction. In fact,the aim oftransformation is notone ofdesigning

formalrulestobe consistent withinformal institutional constraints, buttotransform

theexistinginstitutional endowment forspecificpurposes.Thisis complicated in the

framework duetoa thirdproblem, the

namely conflating ofdimensions ofinstitutions

withtheframework ofinstitutions themselves. NormsintheVebleniansenseof"hab-

itsofthoughtcommontothegenerality ofmenand women"can be institutions them-

selves.Thus,ideologyand historyplay a centralrolein creatingthe framework of

institutional while

transformation, organizations, or even interest groups, are an impor-

tantdimension ofinstitutions in thesenseofconcatenating peoplein a structure with

commonrulesand purposes.Lumpingall thesetogetheras informal institutions is

ratherconceptually problematic.

A greatdeal ofbackingoftheimportance ofinstitutions emanatesfromtheimper-

fectinformation school(forexample,Stiglitz,[1985,1994]).Imperfect information in

thefinancial markets dictates theexistence ofinformation-gathering institutions. Institu-

tionsmatter, therefore, especiallythoseofthefinancialintermediation variety.Under

such circumstances, the structureoffinance,debtversusequity,becomesofpara-

mountimportance. Threeschoolsofthoughtcan be identified onthisscore:thebank-

based view,whichemphasizesthepositiveroleofbanksin development and growth

[Gerschenkron, 1962;Stiglitz,1985;Singh,1997];themarket-based view,whichhigh-

lightsthe advantagesofwell-functioning markets[Beckand Levine,2002]; and the

financialservicesview,accordingto whichneitherbanksnormarketsmatter - it is

financialservicesthemselvesthatare byfarmoreimportant thantheformoftheir

delivery. They are different components of thefinancial system;theydo notcompete,

and as such amelioratedifferent costs, transaction and information, in the system

[Boydand Smith,1998].These viewsare concernedwithbuildinginstitutions that

supportthedevelopment ofmarkets.The workingsoftheseinstitutions becomethe

focusoftheanalysis,especiallytheregulatory aspectsoftheinstitutional framework.6

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TO FINANCIALLIBERALIZATION

ALTERNATIVES THEORY 257

Whileinformation gatheringis an important aspectofinstitutional design,it is

onlyonedimensionoffinancialinstitutions. We proposegoingbeyondtheideas that

underliethoseofthe imperfect information school,and also beyondthe misleading

distinctionbetweenformalandinformal institutions,toan institutional-centric theory

ofthetransformation ofa developmentally orientedfinancialsystem.It is important

to distinguish institutional forcesfrominstitutional purposesand institutional out-

comesin termsofthegenesis,evolution, and maturationofinstitutions. Forconcep-

tual clarity,thereneeds to be a carefulunderstanding ofthe relationshipbetween

institutionalcontexts andpotentialinstitutional transformation paths.Financialsys-

temscan be disaggregated intofiveinstitutionally relatedcomponents thatare inter-

activein producing particular outcomes. Each operates in a particularinstitutional

context.Thefivecomponents arenorms, incentives,regulations, andorganizations.7

capacities,

In thecontextoffinancialsystems,normsare habitsofthoughtthatarise from

socialesteemandsanctionsderivedfrom establishedpatternsofbanking.Theyinvolve

rulesofthumb,thedevelopment oftrustand professional habitsthatencouragepro-

bity,and theproperconductthatis thebackboneofbanking.Whiletheseare central

to the development and operationofanybankingsystem,bankingfordevelopment

mustalso incorporate normsthat encouragethe extensionoftimehorizonsas an

integralpart ofintermediation.

Incentivesfocuson therewardsand penaltiesthatarisefromdifferent modesof

behavior.The institutional-centric viewofincentivesis dissimilartomarginalcalcu-

latingutilitymaximizersembeddedin neoclassicaleconomics.First,incentivesare

notsimplydeliveredvia marketsbutcan arisewithina varietyofdifferent organiza-

tionalconstructs. Second,humansare foremost socialbeingswhoare motivatedby

rewardsand penaltiesthatgowellbeyondincomeormaterialfactors.In thecontext

ofbanking,financialvariableslikeinterestratesare onlyonedimensionofa variety

offactorsthatshape bankingdecisionsand behavior.Promotions, the loss ofsocial

esteem,threatsofostracism,socialresponsibility, legal repercussions, professional-

ism, and pride,etc., are all central to generating the incentives for expandingand

operating in

bankingsystems developing countries.

Regulationsconstitute thelegalboundariesthathelpsettherulesofoperationin

financialsystems.The regulatory dimensionsare wellknownand includeprudential

guidelines on the provisions forand categorization ofassetrisk;accounting standards;

auditingschedules;deposit insurance stipulations;capitalrequirements; licensingrules

and procedures;regulationon interestrate determination and interbankmarkets;

scopeofoperationsin termsofthetypesoffinancialdevicessold;and property right

issues,including rules to access collateral when loan payments are in default, etc.

Whatis particularly important is a careful specification ofthe spheres ofinteraction

amongthecomponents oftheeconomy, includingownership amongthedifferent seg-

mentsofthefinancialsystemand theirlinkagetoindustrial,agricultural, and other

servicesectors.One ofthereasonswhyempiricaltestingbetweenfinanceand growth

is so indeterminate is preciselybecause cases ofsuccessfulbankingin developing

countrieshave arisenwhenthereis a dynamicinterface amonginvestment, produc-

tion,and banking.

The issue oflegallysettingoutincentivesto loan,monitor, and superviseactivi-

tiesthathave higherriskbutare moredevelopmental becomesan important partof

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

258 EASTERNECONOMICJOURNAL

thejuridicaldesignoffinancialsystems.An equallyimportant issue is the mecha-

nismstoinstitutionalize thelegalsystemin thesenseofencouraging theinternaliza-

tionoftherulesofoperation.Rewardsand punitivemeasuresmaybe necessaryto

enforce regulationsin theinitialphases.The ultimateaim ofthedesignofanyregu-

latorysystemis tohave monitoring becometheprimefunction and have intervening

enforcement becomethe exception, nottherule.

Capacitiesare relatedtotheunderlying capabilitiesoftheconstitutive members

(individuals and other subunits) of to

organizations operate in an effectivemanner to

achievethegoalsofan organization withintheconfines ofits norms and rules.These

capabilitiesmustbe developedin a consonantmanneron boththe regulatory and

bankingsides. One ofthegreattragediesofliberalization has been the asymmetric

expansionofbankingentitiescomparedto theauditingand otherregulatory capaci-

ties ofsupervisingagencies.Whilenewlegal organizations expandedin places like

Nigeria,thecapabilitiesoftheindividualswithinthesenewstructures wereextremely

weak,providing theopportunity formisuserelativetotheirstatedpurpose.

Organizationsare legallyrecognizedstructuresthat combinegroupsofpeople

withdefinedcommon rulesand purposes.Theyincludebothstateregulatory agencies

andfinancialintermediaries. As intermediaries, countries shouldfocusoncreatingan

assortmentofownershipand bankingtypesto deal withthe multitiered financial

needs ofa developingeconomy(merchant, development, commercial, microfinance,

local,state,international, and cooperativeownership, etc.). In all thesestructures

thestatewillneedto assumeriskbothon thedepositside and loan side (giventhat

themostdevelopmental projectwilloftenhave thehigherrisks).Withoutthesocial-

izationofprivaterisk,it is difficult to see howprivateinvestment and accumulation

will occurin developingcountries.There are manyoptionsforensuringthat the

criteriaforsubsidizationor access to fundsare beingmetand are consistentwith

developmental needs(Korean-style policyloans,Japanesemainbanksystem,busi-

ness-government councils,planningagencies,partialstateownership ofbanks,devel-

opmentalbanks,etc.).To avoidinstability, capitalaccountsneedtobe carefully con-

trolled,includingtheaccessofbankingsystemsto international loans.

Unfortunately, littleofthisis currently happening.In thewakeofthewidespread

failureoffinancialliberalization(includingprivatization to domesticowners)in the

1990s,developingand transitional economieshavebeenturningincreasingly to sell-

ing offfinancialinstitutions to foreignbanks usinga singletypeoforganizational

construct, the commercialbank. The movehas been particularly strongin transi-

tionaleconomieslikeHungaryand theCzechRepublic.The CzechRepublichas paid

an estimated21 percentoftheGDP tocleanup thefinancialsystemafteran exercise

in orthodox liberalization.In response,95 percentofthebankingsectorhas beensold

off.Thefocusofthesebanksis onservicing richerclientsand multinational investors.

Few fundsare beingmadeavailableto domesticinvestors.Small and mediumenter-

prises(SMEs) employnearly60 percentofthecountry's workforce andgenerateabout

40 percentoftheGDP. However,itis estimatedthatonly2 percentofSMEs wereable

toobtaina loan in 2000.Manyare holdingtheirassets in government paperorloans

totheinterbank market{FinancialTimes,2001;November21,2002).Forsomecoun-

tries,likeTanzania,theyhave simplymovedfromstateownership toforeign owner-

ship. While this has avoided the enormously costlyexercisein financialliberalization

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALTERNATIVES

TO FINANCIALLIBERALIZATION

THEORY 259

experiencedby theirneighborsin East Africa,the new foreignbanks are holding

massiveexcessreservesin theformofgovernment paperwithonlyfewloans in the

handsofa handfulofwealthycustomers.Moreover,insteadofaccessingglobalfinance,

banks

foreign in many countries

are national

exporting savingsto saferhavens.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

We have arguedin thispaperthatthefinancialliberalization thesisis weak on

boththeoreticaland empiricalgrounds.An alternativeis desperatelyneeded.We

have sketchedthe essentialsof such an alternative,but moreresearchis clearly

required.At the coreofthe projectis the institutionalizationoffinance.For new

financialsystemstobe institutionalized,

theymustbecomelegitimateentitiesin the

sensethattheyare embeddedin thecircuitsofsocialand economicproduction. Ulti-

for

mately, banking norms to be developmental,they need to be absorbed intothe

consciousnessofthegeneralpopulation, whichis morelikelyto happenwhenstruc-

turesarediverse,

participatory, A beliefthatfinancial

andaccessible. systems indevelop-

ingcountriescan be builtbyadjustingpricesignalsand retracting stateintervention

willcontinuetolead tothechaoswe havewitnessedin manyplacesforfartoomany

years.

NOTES

1. In neoclassicalterms,the first-order conditionforintertemporal utilitymaximization fromcon-

sumption is suchthattheratiobetweenmarginalutilitiesin anytwoperiodsmustbe equal to the

expecteddiscountrate.In thismodel,it is assumedthatfinancialliberalization notonlyraisesreal

interestrates,but also allows individualsnew access to borrowing to smoothconsumption over

timewithina lifecycleframework. In thecredit-constrained world,themarginalutilityofpresent

consumption exceedsthemarginalutilityoffutureconsumption. The newaccessto creditincreases

consumption initiallysincethe consumption oftheyoungrises.The fallin savingsthatresultsis

shortlivedas individualsadjust theirconsumption overtime(consumption will fall as theyget

older).Whatis mostimportant is an increasein sensitivitytovariableslikeinterestrates.A risein

the interestrate decreasesthe incentiveto borrowand lowersthe utilityofconsumption, raising

the inducement to save and loweringthe excessdemandforsavings.See, forexample,Gersovitz

[1988],Bayoumi[1993],and Mavrotasand Kelly [2001].

2. McKinnon[1973] uses a Fisher/Hirshleifer (see, forexample,Hirshleifer[1970]) approachto

capitaltheory, in whichtheutilityofan entrepreneur in intertemporal decisionmakingis related

to threeissues: his endowmentor potentialself-deployed capital,his investment opportunities,

and his marketopportunities forexternallendingor borrowing. In a fragmented markettypicalof

developing countries, the threecomponents ofdecisionmakingare badlycorrelated. For example,

thosewithinternalfundsmighthave fewprofitable opportunities.The wayforward is through the

reductionofthe dispersionofrates ofreturnto a "singleallocativemechanism"that can "accu-

ratelyreflecttheprevailing scarcityofcapital"[McKinnon, 1973,11-12].BydrawingonHirshleifer's

[1970]viewofcapital,McKinnon[1973]is takinga ratherextremeposition,in whichtheinterest

rateis notonlyequal to thereturnto capital- theopportunity costofusinginternalfunds - butit

therateofintertemporal

also reflects preference (forexample, the rate of the

discounting future).

3. The financialliberalizationschoolhas heavilyinfluencedWorldBank thinkingthroughout the

1980sand 1990s.This is evidentthroughout theirownpublications: see, forexample,WorldBank

[1983,58-59;1989,171; 1994,114-115].

4. For mostrecentcross-country exercisesforthis purpose,see Reinhartand Tokatlidis[2002],

Galindo,Micco,and Ordonez[2002],and Bekaert,Harvey,and Lundbrad[2002].

5. Habibullah's[1999]statisticalworkuses Grangercausalitytestsand quarterlydata spanningthe

period 1981-94forseven Asian countries.This periodwas one that exhibiteda good deal of

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

260 EASTERN ECONOMIC JOURNAL

in thesecountries,

financialliberalization including and a varietyofnew

interestrateliberalization

financialinstruments.In fiveof the seven cases the causal relationshipwas fromgrowthto

financeor bi-directionality.

6. This definitionofinstitutions as "rules,enforcement mechanisms,and organizations... that sup-

portmarkettransactions"[WorldBank, 2002, 6] drawson twocontributions. The firstis North

[1990], in which,as mentionedabove, thereis the formal/informal aspect, complemented by

"humanlydevisedconstraints," such as "codesof conduct,""formalrules,"and "laws,"that are

aimed"tocreateorderand reduceuncertainty in exchange"[North,1991,97]. The secondis the

workofNabli and Nugent[1989],whoare concerned withhowinstitutions changewithrespectto

theirorganizational nature.Theirfocusis on the extentto whichinstitutions and organizations

coincide.Our approach,by contrast,looksat fiveinstitutionally relatedbut conceptuallydistinct

components thatinteractto producevalid outcome.

7. See Nissankeand Stein [2003]fora moredetailedbreakdownofthesecomponents.

REFERENCES

Acemoglu D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J., and Thaicharoen, Y. InstitutionalCauses, Macroeco-

nomicSystems:Volatility,Crises and Growth.NBER WorkingPaper 9124. September2002.

The African. June2002.

Akinboade, O. A. FinancialDevelopmentand EconomicGrowthin Botswana:A Test of Causality.

Savingsand Development 22 (3) 1998,331-48.

Arestis,P. and Demetriades, P. FinancialDevelopmentand EconomicGrowth:Assessingthe Evi-

dence.EconomicJournal,May 1997, 783-99.

Arestis,P., Demetriades, P., and Fattouh, B. FinancialPoliciesand theAggregateProductivityof

the Capital Stock:EvidencefromDeveloped and DevelopingCountries."Eastern Economic

Journal,Spring2003, 219-44.

Arestis,P. and Glickman,M. FinancialCrisisin SouthEast Asia: DispellingIllusionthe Minskyan

Way. CambridgeJournalofEconomics,March2002, 237-60.

Armijo, L. MixedBlessing:Expectationsabout ForeignCapital Flows and Democracyin Emerging

Markets.In Financial Globalizationand Democracyin EmergingMarkets,editedbyL. Armijo.

Basingstoke:Macmillan,1999.

Bagehot, W. LombardStreetHomewood,111.:RichardD. Irwin,1873.

Ball, R. The InstitutionalFoundationsof MonetaryCommitment: A ComparativeAnalysis.World

Development, October1999, 1821-42.

Bayoumi, T. FinancialSaving and HouseholdSaving.EconomicJournal,November1993, 1432-43.

Beck, T. and Levine, R. IndustryGrowthand Capital Allocation:Does Havinga Market-or Bank-

Based SystemMatter?NBER WorkingPaper No. 8982,2002.

Bekaert G., Harvey, C. R., and Lundbrad, C. Does FinancialLiberalizationSpur Growth?Paper

presentedat WorldBank Conference May 2002.

on FinancialGlobalization,

Boyd, J. H., and Smith,B. D. The EvolutionofDebt and EquityMarketsin EconomicDevelopment.

EconomicTheory,November1998, 519-60.

Calvo, G. Servicingthe PublicDebt: the Role ofExpectations.AmericanEconomicReview,September

1988,647-61.

Caprio, G. Jr., Atiyas, I., and Hanson, J. A. (eds.) Financial Reform:Theoryand Experience,

Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press, 1994.

Chinn D. M. and Ito, H. Capital AccountLiberalization,Institutionsand FinancialDevelopment:

Cross CountryEvidence."Departmentof Economics,Universityof California-SantaCruz,

2002.

Cho, Y-J. and Khatkhate, D. Lessons of Financial Liberalisationin Asia: A ComparativeStudy.

WorldBank DiscussionPapers,50, Washington, D.C.: WorldBank, 1989a.

20 May

. FinancialLiberalization:Issues and Evidence.Economicand PoliticalWeekly,

1989b.

De Melo, J. and Tybout, J. The EffectsofFinancialLiberalizationon Savingsand Investment in

Uruguay.EconomicDevelopment and CulturalChange,April1986,561-87.

Demirguc-Kunt,A. and Detragiache, E. The Determinants ofBankingCrises in Developingand

DevelopedCountries.IMF StaffPapers,45, 1998,81-109.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALTERNATIVES TO FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION THEORY 261

. FinancialLiberalizationand FinancialFragility.In Proceedings ofthe1998 WorldBank

Conference on Development Economics,editedby B. Pleskovicand J. E. Stiglitz.Washington,

D.C.: WorldBank, 1999.

Dombusch, R. and Reynoso, A. FinancialFactorsin EconomicDevelopment. In PolicyMakingin

theOpenEconomy: Concepts and Case StudiesinEconomicPerformance, editedbyR. Dornbusch.

Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press, 1993.

Financial Times. 12 March1999,

. 12 December2001.

. 21 November2002.

Fry,M. Money,Interestand Bankingin EconomicDevelopment, Baltimore:JohnsHopkinsUniversity

Press, 1988.

Galindo A., Micco, A., and Ordonez, G. FinancialLiberalizationand Growth:EmpiricalEvidence.

Paper presentedat WorldBank Conference on FinancialGlobalization, May 2002.

Gerschenkron,A. EconomicBackwardnessin HistoricalPerspective. A Book ofEssays, Cambridge,

Mass.: HarvardUniversity Press,1962.

Gersovitz, M. Savings and Development.In Handbook of DevelopmentEconomics,edited by H.

Cheneryand S. Srinivasan.Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1988.

Giovannini,A. Savingsand Real InterestRates in LDCs. JournalofDevelopment Economics,18 (2-3)

1985,197-217.

Gonzalez Arrieta, G. M. InterestRates, Savings and Growthin LDCs: An Assessmentof Recent

EmpiricalResearch.WorldDevelopment, May 1988,589-605.

Grabel, I. Speculation-LedEconomicDevelopment:A Post-KeynesianInterpretation of Financial

LiberalizationPrograms.International ReviewofAppliedEconomics,9 (2) 1995, 127-49.

Gupta, K. L. AggregateSavings,FinancialIntermediation and InterestRates. ReviewofEconomics

and Statistics,May 1987,303-11.

Habibullah, M. S. Financial Developmentand EconomicGrowthin Asian Countries:Testingthe

Financial-LedGrowthHypothesis.Savingsand Development, 23 (3) 1999,279-90.

Hellman, T. F., Murdock, K. C, and Stiglitz,J. E. Liberalization, MoralHazard in Banking,and

PrudentialRegulation:Are Capital Requirements Enough?AmericanEconomicReview,March

2000, 147-165.

Hirshleifer,J. Investment, Interestand Capital. EnglewoodCliffs,N.J.:Prentice-Hall, 1970.

Keynes, J. M. The General Theory ofEmployment, and

Interest, Money. New York: Harvest/Harcourt

Brace Johanovich, 1936.

Lewis, P. and Stein, H. The PoliticalEconomyofFinancialLiberalization in Nigeria.In Deregulation

and theBankingCrisisin Nigeria:A Comparative Study,editedby H. Stein,O. Ajakaiye,and

P. Lewis,21-52.Basingstoke:Palgrave,2002.

Lindgreen, C-J.,Garcia, G., and Saal, I. S. Bank Soundnessand Macroeconomic Policy.Washing-

ton,D.C.: International MonetaryFund, 1996.

Matsheka, T. C. InterestRates and the Saving-Investment Processin Botswana.AfricanReviewof

Money,Financeand Banking,(1-2) 1998,5-23.

Mavrotas, G. and Kelly, R. Savings Mobilizationand Financial SectorDevelopment:The Nexus.

Savingsand Development, 25 (1) 2001, 33-64.

McKinnon, R. Moneyand Capital in EconomicDevelopment. Washington, D.C.: BrookingsInstitu-

tion,1973.

. FinancialLiberalisationin Retrospect:InterestRate Policiesin LDCs. In The State of

Development Economics,editedby G. Ranis and T. P. Schultz.Oxford:Basil Blackwell,1988.

. The OrderofFinancial Liberalization.Baltimore:JohnsHopkinsPress, 1993.

Minsky,H. P. Can "It"HappenAgain?Essayson Instability and Finance.Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe,

1984.

Nabli, M. K. and Nugent,J. B., eds. TheNew Institutional Economicsand Development Theoryand

Applicationsto Tunisia. Amsterdam: NorthHolland,1989.

Ndung'u, N. The Impactof Financial SectorLiberalizationon Savings,Investment,Growth,and

FinancialDevelopmentin Anglophone Africa.AfricanDevelopment Review,June 1997,20-51.

Nissanke, M. AfricanExperiencewithFinancialSectorReforms: WhatHas Been AchievedSo Far? In

Deregulationand theBankingCrisisin Nigeria:A Comparative Study,editedby H. Stein,O.

Ajakaiye,and P. Lewis,129-67.Basingstoke:Palgrave,2002.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

262 EASTERN ECONOMIC JOURNAL

Nissanke, M. and Stein, H. FinancialGlobalizationand EconomicDevelopment: Towardan Institu-

tionalFoundation.EasternEconomicJournal,Spring2003, 287-308.

North, D. C. Institutions, InstitutionalChangeand EconomicPerformance. Cambridge:Cambridge

University Press, 1990.

. Institutions.JournalofEconomicPerspectives, Winter1991, 97-112.

Oshikoya, T. W. InterestRate Liberalization, Savings, Investment, and Growth:The Case ofKenya.

Savingsand Development 16, 1992,305-21.

Patrick, H. FinancialDevelopmentand EconomicGrowthin DevelopingCountries.EconomicDevel-

opmentand CulturalChange,14 (2) 1966, 174-89.

Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economicoriginsof Our Time. Boston:

Beacon Press,Inc., 1957.

Reichel, R. The Macroeconomic ImpactofNegativeReal InterestRates in Nigeria:SomeEconometric

Evidence.Savings and Development 15, 1991,273-83.

Reinhart, C. M. and Tokatlidis, L. Beforeand AfterFinancialLiberalization.Paper presentedat

WorldBank Conference on FinancialGlobalization, May 2002.

Robinson, J. The Generalizationofthe GeneralTheory.In The Rate ofInterestand OtherEssays,

editedbyJ. Robinson.London:MacMillan,1952.

Rodrik, D. Trade and Capital AccountLiberalisationin a KeynesianEconomy.JournalofInterna-

tionalEconomics,August1987, 113-29.

. InstitutionsforHigh-Quality Growth:WhatTheyAre and How to AcquireThem.Paper

presentedat the IMF Conference on Second-Generation Reform,8-9 November1999.

Sachs, J. Conditionally, Debt Reliefand the DevelopingCountries'Debt Crisis.In DevelopingCoun-

tryDebt and EconomicPerformance, editedby J. Sachs. Chicago:University ofChicagoPress,

1988.

Sahoo, P., Geethanjali, N., and Kamaiah, B. Savings and EconomicGrowthin India: The Long-

Run Nexus.Savingsand Development 25 (1) 2001, 66-80.

Schumpeter, J. A. The TheoryofEconomicDevelopment. Leipzig:Dunkerand Humblot,1912.

Seek, D. and Yasim, H. E. N. FinancialLiberalization in Africa.WorldDevelopment. November1993,

1867-90.

Shaw, E. Financial Deepeningin EconomicDevelopment. New York:OxfordUniversity Press, 1973.

Sindzingre,A. and Stein, H. Institutions, Development, and GlobalIntegration: A TheoreticalCon-

tribution. CNRS, July2002.

Singh, A. Financial Liberalisation,StockMarketsand EconomicDevelopment.EconomicJournal,

May 1997,771-82.

Stein, H., Ajakaiye, O., and Lewis, P., eds. Deregulationand theBankingCrisis in Nigeria:A

ComparativeStudy.Basingstoke:Palgrave,2002.

Stein,H., Cuesta, M. and McLennon,R. FinancialLiberalization and theJamaicanFinancialDebacle.

Departmentof Economics,RooseveltUniversity, 2002.

Stiglitz,J. E. CreditMarketsand theControlofCapital.JournalofMoney,Credit,and Banking,May

1985,133-52.

. FinancialMarketsand Development.OxfordReviewofEconomicPolicy,Winter1989,

55-68.

. The Role ofthe State in Financial Markets.In WorldBank Proceedingsof the World

Bank Annual Conference on DevelopmentEconomics,1993. Washington,D.C.: WorldBank,

1994.

Taiwo, I. O. A Flow-of-Funds Approachto SavingsMobilizationUsing NigerianData. Savings and

Development, 16 (2) 1992, 168-82.

Underhill, G., ed. The New WorldOrderin International Finance,Basingstoke:Macmillan,1997.

Vera, L. A Chronicleofa LatinAmericanCountryFinancialCrash:The Case ofVenezuela.In Deregu-

lationand theBankingCrisisin Nigeria:A Comparative Study,editedbyH. Stein,O. Ajakaiye,

and P. Lewis,168-92.Basingstoke:Palgrave,2002.

Villanueva, D. and Mirakhor, A. InterestRate Policies,Stabilisationand Bank Supervisionin

DevelopingCountries:StrategiesforFinancialReform. InternationalMonetary Fund Working

Papers,WP/90/8. Washington, D.C.: International MonetaryFund, 1990.

Warman,F. and Thirlwall,A. P. InterestRates,Savings,Investment and Growthin Mexico1960-90:

TestoftheFinancialLiberalization Hypothesis. JournalofDevelopment Studies,April1994,629-649.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ALTERNATIVES TO FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION THEORY 263

Weller, C. Financial Crises and Financial Liberalization:ExceptionalCircumstancesor Structural

Weaknesses?Journalof Development Studies,October2001, 98-126.

World Bank. WorldDevelopment Report,1983. WashingtonD.C., 1983.

. Sub-Saharan Africa,From Crisis to Sustainable Growth:A Long TermPerspective

Study.Washington D.C., 1989.

. The East Asian Miracle:EconomicGrowthand Public Policy.Washington, D.C., 1993.

. Adjustment in Africa,Reforms, Resultsand theRoad Ahead. WashingtonD.C., 1994.

. FinanceforGrowth:PolicyChoicesin a VolatileWorld.A WorldBank PolicyResearch

Report.Washington D.C., 2001.

. WorldDevelopment Report,2002, BuildingInstitutionsforMarkets.Washington, D.C.,

2002.

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Thu, 9 Jan 2014 11:37:32 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Wild - Best Practice in Inventory ManagementDocument295 pagesWild - Best Practice in Inventory ManagementMaría SáenzNo ratings yet

- APQP-ADVANCED PRODUCT QUALITY & CONTROL PLAN 2 ND Edi Manual 115 PagesDocument115 pagesAPQP-ADVANCED PRODUCT QUALITY & CONTROL PLAN 2 ND Edi Manual 115 PagesPaul RosiahNo ratings yet

- Free Siemens NX (Unigraphics) Tutorial - Surface ModelingDocument53 pagesFree Siemens NX (Unigraphics) Tutorial - Surface Modelingitltechnology73% (11)

- SUDHA DairyDocument50 pagesSUDHA DairyAtul Kumar78% (18)

- Micro Matic Student ManualDocument86 pagesMicro Matic Student ManualrtkobyNo ratings yet

- The Components of SQA: 435-INFS-3 Software Quality AssuranceDocument16 pagesThe Components of SQA: 435-INFS-3 Software Quality AssuranceAAMNo ratings yet

- Master in Tourism ManagementDocument2 pagesMaster in Tourism ManagementArchana SarmaNo ratings yet

- HR Internship Resume FormatDocument1 pageHR Internship Resume FormatjennynicholasNo ratings yet

- Sample Thesis Supply Chain ManagementDocument5 pagesSample Thesis Supply Chain Managementvqrhuwwhd100% (2)

- Hazard Identification Process For A Chlor Alkali Operation: AlbertoDocument17 pagesHazard Identification Process For A Chlor Alkali Operation: AlbertoRathish RagooNo ratings yet

- 10118919305301003Document2 pages10118919305301003Parth ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Fantasy Fashions Had Used The Lifo Method of Costing InventoriesDocument6 pagesFantasy Fashions Had Used The Lifo Method of Costing Inventorieslaale dijaanNo ratings yet

- Lockbox AgreementDocument4 pagesLockbox AgreementL Joshua EikovNo ratings yet

- BMM 2021 Assignment 1Document1 pageBMM 2021 Assignment 1Ishita jain-RM 20RM921No ratings yet

- Nalla Malla Reddy Engineering College: Notes of Unit-1Document8 pagesNalla Malla Reddy Engineering College: Notes of Unit-1VIJETHA RINGU100% (1)

- Block-05 Case Studies On Development Planning and Management PDFDocument62 pagesBlock-05 Case Studies On Development Planning and Management PDFrameshNo ratings yet

- Catalogo Cabo MilitarDocument80 pagesCatalogo Cabo MilitarCesar MarquesNo ratings yet

- Adani Power LTD - 20 PDFDocument258 pagesAdani Power LTD - 20 PDFAbhishek MurarkaNo ratings yet

- QUIZ No. 1Document6 pagesQUIZ No. 1Kathleen FrondozoNo ratings yet

- Finance (Salaries) Department: Loans and Advances by The State Government - Advances ToDocument2 pagesFinance (Salaries) Department: Loans and Advances by The State Government - Advances ToGowtham RajNo ratings yet

- Terms and Conditions Current Account/Current Account-I or Savings Account/Savings Account-I (CASA/CASA-i) Double Cash Bonus Campaign 2.0Document12 pagesTerms and Conditions Current Account/Current Account-I or Savings Account/Savings Account-I (CASA/CASA-i) Double Cash Bonus Campaign 2.0mohd addinNo ratings yet

- Zl-Mutual NdaDocument9 pagesZl-Mutual NdapavanNo ratings yet

- 6th Merit List of UG Vacant SeatDocument4 pages6th Merit List of UG Vacant SeatRavindra RathoreNo ratings yet

- Marketing Plan Sample1Document25 pagesMarketing Plan Sample1NoreL Jan PinedaNo ratings yet

- In Partial Fulfillment of MarDocument27 pagesIn Partial Fulfillment of Marnathan casinaoNo ratings yet

- Curiculum Vitae: ExperienceDocument12 pagesCuriculum Vitae: ExperienceDesi Hendaryanie WiramiharjaNo ratings yet

- Practice Test 3-Date 9.3Document9 pagesPractice Test 3-Date 9.3Bao TranNo ratings yet

- 000Document8 pages000DUAA ALJEFFRINo ratings yet

- Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth Group 3Document17 pagesSustainable Development Goals: Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth Group 3Toby ChungNo ratings yet

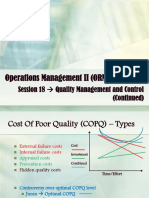

- ORM2BJ (D) 22-3 - Session 18Document16 pagesORM2BJ (D) 22-3 - Session 18mohit9811No ratings yet