Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Audit of Mental Capacity Assessment by Primary Care Physicians Versus Consultation-Liaison Psychiatrists

Uploaded by

melissaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Audit of Mental Capacity Assessment by Primary Care Physicians Versus Consultation-Liaison Psychiatrists

Uploaded by

melissaCopyright:

Available Formats

East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:95-100 | DOI: 10.

12809/eaap1752 Original Article

Audit of Mental Capacity Assessment by

Primary Care Physicians Versus Consultation-

liaison Psychiatrists

CYW Chan, SWL Yong, AS Mhaisalkar, GL Sin, SH Poon, SM Tan

Abstract

Objective: To review the mental capacity assessment of in-patients referred to consultation-liaison

psychiatrists and to compare the assessment first made by primary care physicians.

Methods: Medical records of in-patients who were referred to consultation-liaison psychiatrists for mental

capacity assessment between May and October 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Assessment was first

made by a primary care physician; complex cases were referred to a consultation-liaison psychiatrist.

Audit of each case note was conducted independently by at least two of the authors.

Results: Medical records of 37 female and 26 male in-patients aged 24 to 91 (mean, 68.2) years were

audited. Only 33.3% of these patients had no psychiatric diagnosis. Overall, assessments by primary

care physicians were suboptimal. Assessments by consultation-liaison psychiatrists were more detailed,

with documentation of mental capacity (93.7%) and psychiatric diagnosis (88.9%). Nonetheless, patient

wishes and beliefs were poorly documented (19.0%), as were whether the patient had a lasting power

of attorney or a court-appointed deputy (6.3%) and whether the patient had made advance care planning

(0%).

Conclusion: Overall, mental capacity assessment was inadequately performed by primary care physicians

and consultation-liaison psychiatrists. More work needs to be done to engage, educate, and empower all

stakeholders involved.

Key words: Clinical audit; Mental competency

Clarice Yi Wen Chan, GCE A levels, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National the court to appoint a deputy to make decisions.1 This

University of Singapore, Singapore

Samantha Wei Lee Yong, GCE A levels, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine,

legislation was first passed in the United Kingdom in

National University of Singapore, Singapore 2005 to address caretaker concerns about the lack of legal

Abhishek Subodh Mhaisalkar, GCE A levels, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, guidance in decision making. It has since been adopted by

National University of Singapore, Singapore

Dr Gwen Li Sin, MD, MMED (Psychiatry), Singapore General Hospital,

New Zealand, Australia, Ireland, and Singapore.

Singapore Advance care planning is a non-legal series of

Dr Shi Hui Poon, MD, MRCPsych (UK), Singapore General Hospital, discussion among a patient, trusted person(s), and

Singapore

Dr Shian Ming Tan, MD, MMED (Psychiatry), Singapore General Hospital,

physicians to facilitate sharing and recording of the patient’s

Singapore personal beliefs, values, and goals of care. It guides the

trusted person(s) and physicians in decision making should

Address for correspondence: Dr Shian Ming Tan, Singapore General Hospital,

Outram Road, Singapore 169608. Email: tan.shian.ming@singhealth.com.sg

the patient become mentally incapacitated or be unable to

make/convey decisions.2

Primary care physicians are required to assess the

mental capacity of the patient, with the presumption that the

patient has mental capacity. They must determine whether

Introduction the patient is able to understand, retain, and weigh the

relevant information as part of the decision-making process

In Singapore, the Mental Capacity Act sets a legal framework and if he/she can communicate said information. Details

to allow individuals aged ≥21 years to appoint in advance, should be documented in the case notes, along with the

trusted person(s) to make decisions (concerning personal impression of the patient’s mental capacity and reasons to

welfare, healthcare, and assets) on their behalf in the event support the judgement, as should details of any lasting power

they lose mental capacity (temporarily or permanently) by of attorney or advance care planning and consultations with

signing a lasting power of attorney to legalise appointment trusted persons on patient wishes.3

of proxies. Should one become mentally incapacitated Nonetheless, inadequate assessment has resulted

before making a lasting power of attorney, the Act allows in incapacitated patients not being assessed as such, or

© 2018 Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 95

CYW Chan, SWL Yong, AS Mhaisalkar, et al

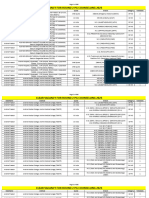

being treated without true valid consent,4,5 with a lack of or Table 1. Reasons for referral to psychiatrist.

minimal documentation.6 Patients may be determined to be

Reason for referral to No. (%) of patients

incapacitated if the physician sets the threshold too high and

psychiatrist (n = 63)*

does not take all reasonable steps to improve the patient’s

decision-making capacity. This raises concerns about abuse Treatment consent 17 (25.3)

of the assessment. Patients are then vulnerable to coercion Placement 16 (23.9)

from family members and physicians, and their freedom of

Operation consent 13 (19.4)

action severely restricted.7

In Singapore, primary care physicians assess the Discharge 12 (17.9)

mental capacity of every patient; a second opinion from Others 4 (6.0)

a consultation-liaison psychiatrist is sought when there is

Procedure 2 (3.0)

any doubt, usually if the patient has a mental disorder. This

study aimed to review the mental capacity assessment of Legal 2 (3.0)

in-patients referred to consultation-liaison psychiatrists Unclear 1 (1.5)

and to compare the assessment first made by primary care *

Some patients had multiple reasons for referral

physicians.

Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the SingHealth

Central Institutional Research Board. Patient consent was Table 2. Psychiatric diagnosis of patients.

waived. Medical records of Singapore General Hospital Psychiatric diagnosis No. (%) of

in-patients who were referred to consultation-liaison patients (n = 63)

psychiatrists for mental capacity assessment between

May and October 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. Dementia and cognitive impairment 16 (25.4)

Assessment was first made by a primary care physician; Delirium 10 (15.9)

complex cases were referred to a consultation-liaison Schizophrenia or psychotic disorders 4 (6.3)

psychiatrist.

Two of the authors independently reviewed the Depression 3 (4.8)

previous assessment tools and standards8 and each Others 2 (3.2)

developed an audit framework. The final audit framework Unknown 1 (1.6)

was developed after consensus on what was culturally and

legally relevant in the local context (Appendix). Patient More than one psychiatric diagnosis *

6 (9.5)

characteristics were recorded, along with whether patient None 21 (33.3)

family and/or legal representatives (e.g. lasting power of *

Usually a known past psychiatric condition in the background

attorney) were consulted. of newly diagnosed dementia or delirium

Audit of each case note was conducted independently

by at least two of the authors. Responses were tallied

and discrepancies resolved by consensus. Data were

dichotomised according to whether they had been elicited

or not; data that were not documented were considered not

elicited. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

Frequency of responses and trends were tabulated. Prior to referral to the psychiatric team, most primary

care physicians had determined if the patient had impaired

Results functioning of the mind (71.4%) and had actively engaged

the patient’s family or close acquaintances in patient care

Medical records of 37 female and 26 male in-patients (80.9%) [Table 3]. Nonetheless, they seldom sought the

aged 24 to 91 (mean, 68.2) years were audited. Requests family’s opinion of the patient’s values and pre-expressed

for assessment were sometimes incomplete and were wishes (11.1%). In contrast, assessments conducted by the

embedded in referrals for psychiatric management. The psychiatric team were more detailed, with documentation

main reasons for referral for mental capacity assessment of mental capacity (93.7%) and psychiatric diagnosis

were: treatment consent (25.3%), placement (23.9%), (88.9%). Nonetheless, patient wishes and beliefs were

operation consent (19.4%), and discharge (17.9%) [Table poorly documented (19.0%), as were whether the patient

1]. Of these patients, 25.4% were diagnosed with dementia had a lasting power of attorney or a court-appointed deputy

and cognitive impairment and 15.9% with delirium. Only (6.3%) and whether the patient had made advance care

33.3% had no psychiatric diagnosis (Table 2). planning (0%).

96 East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018, Vol 28, No.3

Audit of Mental Capacity Assessment

Table 3. Comparison of primary care physicians with consultation-liaison psychiatrists in terms of completion of

assessment.

Item Completion of assessment (No. [%] of patients)

Primary care physicians Consultation-liaison

psychiatrists

Condition 37 (58.7) -

Treatment alternatives 21 (33.3) -

Consequences of options 25 (39.7) -

Consequences of no action 17 (27.0) -

Impairment 45 (71.4) 62 (98.4)

Understand 25 (39.7) 51 (81.0)

Retain 23 (36.5) 49 (77.8)

Weigh 14 (22.2) 47 (74.6)

Communicate 33 (52.4) 52 (82.5)

Mental capacity 7 (11.1) 59 (93.7)

Identify substitute 51 (81.0) -

Opinion substitute 7 (11.1) -

Question clear 51 (81.0) -

Speak to others for background information - 39 (61.9)

Psychiatric diagnosis - 56 (88.9)

Speak to others for patient’s preferences and values - 12 (19.0)

Advance care planning - 0 (0)

Lasting power of attorney - 4 (6.3)

Recommend reassessment - 16 (25.4)

Reassessment completed - 13/16 (81.3)

Mental capacity - 10/16 (62.5)

Discussion survey to assess doctors’ knowledge of the Act, only 70%

of doctors in an emergency department were able to outline

Documentation of mental capacity assessment by primary the steps involved in mental capacity assessment.10 It seems

care physicians was inadequate, consistent with findings that doctors have failed to keep pace with rapidly evolving

of previous audits.4,6 Inadequate documentation may be medical practice and have not developed the appropriate

due to time pressure or reluctance to alter routine care and new skill sets.

undermine the doctor-patient relationship.4 In our audit, only 11.1% of primary care physicians

Assessment of mental capacity is in two stages: documented their impression of the patient’s mental capacity

(1) establishing impairment of the mind and that (2) the prior to referral to the psychiatry team. They may have felt

impairment causes inability to make a decision. In our audit, that there was no role for them given that they had already

primary care physicians were particularly inadequate at solicited input from the psychiatry team. Nonetheless, there

assessing how the impairment affected the patient’s ability is no mandate that mental capacity assessment be performed

to understand/retain/weigh information and communicate only by a psychiatrist. Primary care physicians are qualified

the decision. One explanation is that most primary care to perform mental capacity assessment11 because (1) they

physicians erroneously assume that patients ‘automatically’ know the patient’s medical circumstances and the question

lack mental capacity in the presence of an active psychiatric to be decided; (2) they are in the best position to know the

illness.9 Primary care physicians may be ill-equipped to patient’s and family’s values and cultural and religious

assess mental capacity based on the Code of Practice. In a views; (3) they know the patient’s medical history so the

East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018, Vol 28, No.3 97

CYW Chan, SWL Yong, AS Mhaisalkar, et al

assessment is longitudinal based on multiple interactions; Evaluation is an eight-question tool that takes about 10

and (4) they are in the best position to re-evaluate mental to 20 minutes to complete; it has good agreement with

capacity because of their ongoing medical relationship with assessment by a forensic psychiatrist.17 The tool is mainly

the patient. Psychiatrists are no better at assessing mental used in Canada but can be adapted for more widespread use.

capacity than physicians.12 A flowchart should be made available to assist clinicians

Documentation of informed consent was scant. In with the due process when arriving at decisions in the best

an audit of 1057 outpatients in the offices of primary care interests of an incapacitated individual. Patients should be

physicians and surgeons, only 9% were deemed to have given written information about advance care planning and

the necessary information to make an informed decision.13 the Act regarding execution of lasting power of attorney.

Among 141 cases in whom orthopedic surgical interventions They should be engaged early in advance care planning

were discussed, no case had all elements fully discussed, based on their wishes and intent rather than deferring to the

with only 62% being informed of alternatives and 59% last minute.

advised about any pros and cons.14 The concept of informed

consent is based on the ethical principle of the right to Conclusion

self-determination. Informed consent means that patients

must be given options to choose, and not just information Mental capacity assessment was inadequately performed

about one line of treatment. Although mental capacity by primary care physicians and consultation-liaison

of our patients is likely to be questionable, omission of psychiatrists. More work is necessary to engage, educate,

informed consent based on a doctor’s impression of the and empower all stakeholders involved.

patient’s mental capacity cannot be justified. Such cases are

contentious and increase the risk of litigation. Acknowledgement

Consultation-liaison psychiatrists rarely enquired

patients about advance care planning or lasting power The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

of attorney. Even when a substitute decision-maker was

References

identified, discussion invariably focused on what the

substitute decision-maker wanted for the patient, not what 1. Mental Capacity Act (Chapter 177A). Singapore Statutes Online;

the patient wanted based on their prior wishes and values. 2008.

2. Advance Care Planning. Agency of Integrated Care. Singapore Silver

Most patients who lacked mental capacity did not have a

Pages. National Medical Ethics Committee; 2009.

reassessment recommended or completed. Reasons for 3. Code of Practice: Mental Capacity Act (Chapter 177A). Office of the

this include limited understanding of the Act and their Public Guardian; 2008.

obligations,15 and the belief that patients do not utilise 4. Sleeman I, Saunders K. An audit of mental capacity assessment on

the provisions of the Act. This inevitably undermines general medical wards. Clin Ethics 2013;8:47-51. cross ref

5. Spencer BW, Wilson G, Okon-Rocha E, Owen GS, Wilson Jones C.

the intention of the Act to promote patient autonomy in

Capacity in vacuo: an audit of decision-making capacity assessments

decisions related to care, treatment, and well-being. in a liaison psychiatry service. BJPsych Bull 2017;41:7-11. cross ref

There are limitations to our study. Assessments that 6. Sorinmade O, Strathdee G, Wilson C, Kessel B, Odesanya O. Audit

did not refer to consultation-liaison psychiatrists were not of fidelity of clinicians to the Mental Capacity Act in the process of

audited. It is possible that primary care physicians had capacity assessment and arriving at best interests decisions. Qual

Ageing Older Adults 2011;12:174-9. cross ref

performed a complete assessment, and that assessment

7. Stewart R, Bartlett P, Harwood RH. Mental capacity assessments and

of the referred cases was incomplete because the primary discharge decisions. Age Ageing 2005;34:549-50. cross ref

care physicians assumed that it would be completed by 8. The British Psychological Society. Professional Practice Board and

the consultation-liaison psychiatrists. It is possible that Social Care Institute for Excellence; c 2000 - 2017. Audit Tool for

assessments were indeed thorough verbally, just without Mental Capacity Assessments. Available from www.bps.org.uk/

sites/default/files/.../audit-tool-mental-capacity-assessments_0.pdf.

documentation in the case notes. The issue is thus not

Accessed 24 Jan 2018.

inadequate assessment but rather shoddy documentation. 9. Schofield C. Mental Capacity Act 2005–what do doctors know? Med

In addition, the findings of this local audit may not be Sci Law 2008;48:113-6. cross ref

applicable to other regions. Nonetheless, we separately 10. Evans K, Warner J, Jackson E. How much do emergency healthcare

audited the performance of the primary care physicians workers know about capacity and consent? Emerg Med J 2007;24:391-

3. cross ref

and consultation-liaison psychiatrists to explore the pitfalls

11. Tunzi M. Can the patient decide? Evaluating patient capacity in

committed by the former and the added value of the latter. practice. Am Fam Physician 2001;64:299-306.

Primary care physicians should adequately document 12. Markson LJ, Kern DC, Annas GJ, Glantz LH. Physician assessment of

their assessment of mental capacity before referring patients patient competence. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:1074-80. cross ref

for psychiatry consultation. Information should be made 13. Braddock CH 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson

accessible to enhance clinician adherence to the Mental W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to

basics. JAMA 1999;282:2313-20. cross ref

Capacity Act Code of Practice. The use of a structured 14. Braddock C 3rd, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, Bereknyei S, Frankel RM,

assessment format is recommended. A systematic review has Levinson W. “Surgery is certainly one good option”: quality and time-

evaluated several assessment tools.16 The Aid to Capacity efficiency of informed decision-making in surgery. J Bone Joint Surg

98 East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018, Vol 28, No.3

Audit of Mental Capacity Assessment

Am 2008;90:1830-8. cross ref medical decision-making capacity? JAMA 2011;306:420-7. cross ref

15. Jackson E, Warner J. How much do doctors know about consent and 17. Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, Singer PA, McKenny J, Naglie

capacity? J R Soc Med 2002;95:601-3. cross ref G, et al. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen

16. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have Intern Med 1999;14:27-34. cross ref

East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018, Vol 28, No.3 99

CYW Chan, SWL Yong, AS Mhaisalkar, et al

Appendix. Audit framework.

Audit standard Remarks

Before referring to psychiatry team… (only consider done if

done before referral)

Before referral to the psychiatry team, did the primary care team

speak to the patient regarding:

• His condition • Condition: ‘Yes’, so long as patient informed of diagnosis

• Treatment options and alternatives • Need both (option and no action) to be told; does not need to

• Consequences that can be expected for each option chosen include alternative procedure/treatment as auditors may not be

• Consequences if no decision is made in the best position to judge/know what these are

• Need consequences for option and no action

Did the team clearly state whether the patient has capacity?

Did the team assess if the patient: ‘Yes’, so long as documented in case notes that patient said yes/no

• Has an impairment of, or disturbed functioning of the mind or

brain

• Can understand the information

• Can retain information

• Can weigh risks and benefits

• Can communicate a decision

Did the team verify if there is an identified substitute decision ‘Yes’, so long as next-of-kin/close acquaintance consulted

maker?

Did the team seek the opinion of the identified substitute decision Opinion of patient’s values and wishes, not their consent

maker?

Is/are the question(s) to be answered stated clearly and

specifically?

Assessment by the psychiatry team… (only considered done

within 72 hours)

Did psychiatry team assess if the patient -

• Has an impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of mind

or brain

• Can understand the information

• Can retain information

• Can weigh risks and benefits

• Can communicate his decision

Did psychiatry team clearly state whether the patient has capacity? ‘Yes’, if mentioned in case notes that unable to assess

Did psychiatry consult relevant parties/next of kin for background ‘Yes’, if psychiatry team spoke to next-of-kin/others

information?

If the patient lacks capacity, did psychiatry team clearly state the

psychiatric diagnosis?

In acting in the best interests of the patient, did psychiatry team ‘Yes’, even if psychiatry team does this on a separate occasion

ascertain the patient’s past/present feelings/wishes and beliefs and after stating impression of patient’s capacity

values by

• Speaking to other individuals who may know the patient well

(this is different to discussing with the family what they would

have wanted for the patient)

• Checking if the patient has made advance care planning

• Checking if the patient has a lasting power of attorney/court-

appointed deputy

If the patient lacks capacity, did psychiatry team recommend a ‘Yes’, if mentioned in case notes that psychiatry team will review

re-assessment? later

After assessment by psychiatry team (applies only to those

patients who are deemed by psychiatry to lack capacity)

If a re-assessment was recommended, was the patient re-assessed ‘Yes’ so long as done by primary care team / psychiatry team

at another time?

Did re-assessment clearly state whether the patient has capacity? There must be a definitive answer (“has/no capacity”) by assessor

100 East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018, Vol 28, No.3

Copyright of East Asian Archives of Psychiatry is the property of Hong Kong Academy of

Medicine Press and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print,

download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- 00130478-202105000-00006 Serial Neurologic Assessment in Pediatrics (SNAP) : A New Tool For Bedside Neurologic Assessment of Critically Ill ChildrenDocument13 pages00130478-202105000-00006 Serial Neurologic Assessment in Pediatrics (SNAP) : A New Tool For Bedside Neurologic Assessment of Critically Ill ChildrenYo MeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Critical ThinkingDocument3 pagesChapter 1 Critical Thinkingsam100% (2)

- Language and Students With Mental RetardationDocument22 pagesLanguage and Students With Mental Retardationmat2489100% (4)

- HSR 2179Document13 pagesHSR 2179Lisa SariNo ratings yet

- ndt-18-891Document7 pagesndt-18-891Julio DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18Document6 pagesChapter 18lrdn_ghrcNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Evaluation of The Agitated Patient - Consensus Statement of The American Association For Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA Psychiatric Evaluation Workgroup - PMCDocument9 pagesPsychiatric Evaluation of The Agitated Patient - Consensus Statement of The American Association For Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA Psychiatric Evaluation Workgroup - PMCKaren C. ManoodNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Psychiatry: Paul T. Van Der Heijden, Irma Cefo, Cilia L.M. Witteman, Koen P. GrootensDocument4 pagesComprehensive Psychiatry: Paul T. Van Der Heijden, Irma Cefo, Cilia L.M. Witteman, Koen P. GrootensAnita DewiNo ratings yet

- Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine: SciencedirectDocument5 pagesJournal of Forensic and Legal Medicine: SciencedirectliyaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice Guidelines For Management of SchizophreniaDocument36 pagesClinical Practice Guidelines For Management of SchizophreniajheyfteeNo ratings yet

- Poreddi 2015 Mental Health Literacy Among CaregiDocument6 pagesPoreddi 2015 Mental Health Literacy Among CaregiSantosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Afr 106Document7 pagesAfr 106ribkaNo ratings yet

- Telepsychiatry ConsultationDocument5 pagesTelepsychiatry Consultationleslieduran7No ratings yet

- An Evaluation Study of Schizophrenia National Institute of Mental HealthDocument1 pageAn Evaluation Study of Schizophrenia National Institute of Mental HealthMatthew KennardNo ratings yet

- 2012 Article 2129Document9 pages2012 Article 2129RodrigoSachiFreitasNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceDocument4 pagesEffectiveness of Counselling To Increase The Family of Soul Patients About Drug ComplianceMarlisa LionoNo ratings yet

- Informed Consent and Capacity 2019Document38 pagesInformed Consent and Capacity 2019DewiNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Field Manual - CaliforniaDocument44 pagesMental Health Field Manual - CaliforniaTom RueNo ratings yet

- Da3623 Appendix 1. Beds Luton BPDDocument24 pagesDa3623 Appendix 1. Beds Luton BPDNada KhanNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Emergency Medicine: Amalia MuhaiminDocument22 pagesEthics in Emergency Medicine: Amalia MuhaiminAngkat Prasetya Abdi NegaraNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Trial of Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For DepressionDocument9 pagesA Randomized Trial of Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care For DepressionMoira P. ShawNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nursing JudgementDocument5 pagesClinical Nursing Judgementapi-546503916No ratings yet

- First Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaDocument14 pagesFirst Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaAbirajanNo ratings yet

- Centre For Addiction Mental Health - SkinnerDocument8 pagesCentre For Addiction Mental Health - SkinnerAmelia NewtonNo ratings yet

- 2011 Detection of Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care Friendly)Document9 pages2011 Detection of Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care Friendly)rocksurNo ratings yet

- Patient Autonomy and Informed ConsentDocument10 pagesPatient Autonomy and Informed ConsentShreeyaNo ratings yet

- End of Life CareDocument18 pagesEnd of Life CareselvarajNo ratings yet

- Advance DirectiveDocument5 pagesAdvance DirectiveVidushi SinghalNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychological Assessment: Principles, Pearls and PerilsDocument8 pagesNeuropsychological Assessment: Principles, Pearls and Perilsnellianeth orozco garciaNo ratings yet

- USA Atencion PrimariaDocument12 pagesUSA Atencion PrimariaClaudia Evelyn Calcina MuchicaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0003999320303841 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0003999320303841 MainAFRIDATUS SAFIRANo ratings yet

- 12 Mental Health SBA-1Document23 pages12 Mental Health SBA-1Arjun KumarNo ratings yet

- Psychdrugforpeds PDFDocument22 pagesPsychdrugforpeds PDFAnna HungNo ratings yet

- (10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Informed Consent in Neurosurgery - A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pages(10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Informed Consent in Neurosurgery - A Systematic ReviewOnilis RiveraNo ratings yet

- Informed Consent and The AnaesthesiologistDocument4 pagesInformed Consent and The AnaesthesiologistdrbadontaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice in Management of Patients With Mental Health Disorders in Emergency Departments in Makkah Region of Saudi ArabiaDocument8 pagesKnowledge, Attitude, and Practice in Management of Patients With Mental Health Disorders in Emergency Departments in Makkah Region of Saudi ArabiaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Crisis Counselling - Caring People With Mental DistubancesDocument6 pagesCrisis Counselling - Caring People With Mental DistubancesVictor JamesNo ratings yet

- 1.1.capacity To Consent For Treatment in Patients With Psychotic Disorder A Cross-Sectional Study From North KarnatakaDocument6 pages1.1.capacity To Consent For Treatment in Patients With Psychotic Disorder A Cross-Sectional Study From North KarnatakaJulio DelgadoNo ratings yet

- 2470 PDFDocument8 pages2470 PDFPreetha Kumar AJKKNo ratings yet

- Judges Guide To Mental Health DiversionDocument20 pagesJudges Guide To Mental Health DiversionAaron ArnoldNo ratings yet

- APA Resource DocumentDocument17 pagesAPA Resource DocumentAxel Robinson HerreraNo ratings yet

- The Psychiatric Assessment NotebookDocument4 pagesThe Psychiatric Assessment NotebookSean Goddard NPNo ratings yet

- Effects of Physical Therapy On Mental Function in Patients With StrokeDocument6 pagesEffects of Physical Therapy On Mental Function in Patients With StrokeTeuku FadhliNo ratings yet

- AHRQ Research in Action: Advance Care PlanningDocument20 pagesAHRQ Research in Action: Advance Care PlanningNational Healthcare Decisions DayNo ratings yet

- 1 Critical Thinking and The Nursing ProcessDocument12 pages1 Critical Thinking and The Nursing ProcessANA CATARINA DOS SANTOS OLIVEIRA100% (1)

- LL LLLLL LLLLLDocument22 pagesLL LLLLL LLLLLalwanNo ratings yet

- CU02A WEEK02-NursingProcessinPMHNPractice28VAL2928129MODULEDocument8 pagesCU02A WEEK02-NursingProcessinPMHNPractice28VAL2928129MODULEduca.danrainer02No ratings yet

- Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) : Expanded VersionDocument29 pagesBrief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) : Expanded VersionNungki TriandariNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Contemporary Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing 3rd Edition Carol R KneislDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Contemporary Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing 3rd Edition Carol R Kneislbustcrouchvquc1100% (48)

- Assessment Writeup FinalDocument31 pagesAssessment Writeup FinalKkrNo ratings yet

- Livro - Foundation of Mental Health CareDocument459 pagesLivro - Foundation of Mental Health CareDesiree Dias100% (1)

- A Case For Psychiatric Leadership in Dispositional Capacity AssessmentDocument3 pagesA Case For Psychiatric Leadership in Dispositional Capacity AssessmentRicardo EscNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument9 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kedokteran Dan Kesehatan IndonesiaDocument8 pagesJurnal Kedokteran Dan Kesehatan IndonesiaFatmanisa LailaNo ratings yet

- Patient Instructions: Name of Patient: MR Lur PakDocument7 pagesPatient Instructions: Name of Patient: MR Lur PaksarfirazNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Clinical AssessmentDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Clinical AssessmentJahnaviNo ratings yet

- CORONA VIRUS - PublishedDocument8 pagesCORONA VIRUS - PublishedPremkant UparikarNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document21 pagesUnit 1DENNIS N. MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Your Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022From EverandYour Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022No ratings yet

- Finding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareFrom EverandFinding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareNo ratings yet

- Your Child's First Consultation Questions You Should Ask Your 31st Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 22, 2022From EverandYour Child's First Consultation Questions You Should Ask Your 31st Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 22, 2022No ratings yet

- Tashi Report Revised 16feb2021Document63 pagesTashi Report Revised 16feb2021MAHassanChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Dermawound Original Venous Stasis Wound CareDocument8 pagesDermawound Original Venous Stasis Wound CareNew Medical Solutions - Your Source for Dermawound, BurnBGone and more...No ratings yet

- Case 24-2022: A 31-Year-Old Man With Perianal and Penile Ulcers, Rectal Pain, and RashDocument10 pagesCase 24-2022: A 31-Year-Old Man With Perianal and Penile Ulcers, Rectal Pain, and RashCorina OanaNo ratings yet

- Cancer and Oncology Nursing NCLEX Practice Quiz ANSDocument5 pagesCancer and Oncology Nursing NCLEX Practice Quiz ANSyanyan cadizNo ratings yet

- Chronic Sialadenitis With Sialolithiasis Associated With Parapharyngeal Fistula and TonsillolithDocument4 pagesChronic Sialadenitis With Sialolithiasis Associated With Parapharyngeal Fistula and TonsillolithguleriamunishNo ratings yet

- TS Nicaragua Health System RPTDocument74 pagesTS Nicaragua Health System RPTAlcajNo ratings yet

- Ncma219 Course Task 3Document18 pagesNcma219 Course Task 3NikoruNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse and Neglect-Dr - Anisha NandaDocument49 pagesChild Abuse and Neglect-Dr - Anisha NandaHaripriya SukumarNo ratings yet

- INDIVIDUAL Assignment For The Course Inclusiveness (SNIE 1012) (15%) For Engineering S and Applied A, B, & C Groups Instruction I: Choose The Best Answer For The Ten Questions That FollowDocument3 pagesINDIVIDUAL Assignment For The Course Inclusiveness (SNIE 1012) (15%) For Engineering S and Applied A, B, & C Groups Instruction I: Choose The Best Answer For The Ten Questions That FollowErmi ZuruNo ratings yet

- Social Perspectives - Unit 10 - Task 1 - Copy 123Document13 pagesSocial Perspectives - Unit 10 - Task 1 - Copy 123zxko24No ratings yet

- The Impact of The Peepoo Scheme On EducationDocument1 pageThe Impact of The Peepoo Scheme On EducationDa BestNo ratings yet

- The Health Promotion Model by Nola J PanderDocument9 pagesThe Health Promotion Model by Nola J PanderJek Amidos PardedeNo ratings yet

- HEALTH-TEACHING-PLAN sUGATON EVALDocument9 pagesHEALTH-TEACHING-PLAN sUGATON EVALPrincess Faniega SugatonNo ratings yet

- H02E Assignment 8Document4 pagesH02E Assignment 8Good ChannelNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (Ri)Document50 pagesAntimicrobial Stewardship Program (Ri)Erni Yessyca SimamoraNo ratings yet

- Clear Vacancy R2Document696 pagesClear Vacancy R2bhuviNo ratings yet

- Glasgow Come ScaleDocument11 pagesGlasgow Come ScaleMaria Jose Gonzalez SarangoNo ratings yet

- Bacteria Resistance To Antibiotics Science Fair ProjectDocument3 pagesBacteria Resistance To Antibiotics Science Fair ProjectZaina ImamNo ratings yet

- Pa Australian Guidelines On Adhd Draft PDFDocument291 pagesPa Australian Guidelines On Adhd Draft PDFJonNo ratings yet

- Antihypertensive Drugs - Classification and SynthesisDocument14 pagesAntihypertensive Drugs - Classification and SynthesisCường NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Task 2 Engineering English (Redho Triwinoko, METO 5B)Document3 pagesTask 2 Engineering English (Redho Triwinoko, METO 5B)Redho TriwinokoNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Controversies: Antmi Yric Prophylaxis in Cesarean SectionDocument6 pagesTherapeutic Controversies: Antmi Yric Prophylaxis in Cesarean Sectionnurul wahyuniNo ratings yet

- Adnexal Torsion: Clinical, Radiological and Pathological Characteristics in A Tertiary Care Centre in Southern IndiaDocument6 pagesAdnexal Torsion: Clinical, Radiological and Pathological Characteristics in A Tertiary Care Centre in Southern IndiaKriti KumariNo ratings yet

- Increased Intracranial PressureDocument10 pagesIncreased Intracranial Pressureapi-3822433100% (10)

- UNICEF Innocenti Prospects For Children Global Outlook 2023Document53 pagesUNICEF Innocenti Prospects For Children Global Outlook 2023sofiabloemNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0895435615000141 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0895435615000141 MainBarron ManNo ratings yet

- Fetal Growth Restriction Acog 2013Document14 pagesFetal Growth Restriction Acog 2013germanNo ratings yet

- InsuracneDocument4 pagesInsuracnesathishbabuNo ratings yet

- Tuansi-Pa ManuscriptDocument11 pagesTuansi-Pa Manuscriptallkhusairy6tuansiNo ratings yet