Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taylor & Francis, LTD

Uploaded by

LazarovoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taylor & Francis, LTD

Uploaded by

LazarovoCopyright:

Available Formats

The Birth of the Judson Dance Theatre: "A Concert of Dance" at Judson Church, July 6, 1962

Author(s): Sally Banes

Source: Dance Chronicle, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1982), pp. 167-212

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1567516 .

Accessed: 26/06/2014 08:27

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Dance

Chronicle.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Birth of the Judson Dance Theatre:

"A Concert of Dance" at Judson Church,

July 6, 1962

Sally Banes

The Judson Dance Theatre was a loosely organized "collective"

for avant-gardechoreography in Greenwich Village in the early 1960s.

From 1962 to 1964, members of the group met weekly to present

choreography for criticism and they also cooperatively produced

twenty concerts of dance-sixteen group programsand four evenings

of choreography by individuals. The Judson Dance Theatre became

the focus of a new stage in American modern dance, the seedbed

out of which post-modern dance developed over the next two

decades.

The Judson Dance Theatre, which grew out of a choreography

class taught by Robert Dunn, drew on and consolidated various

currents of avant-gardechoreography in the 1950s-most notably

developing from Anna Halprin, James Waring,and Merce Cunning-

ham. It was a vital gathering place for artists in various fields who

exchanged ideas and methods, seeking explicitly to explore, propose,

and refute definitions of dance as an art form. The issues that con-

cerned the group ranged from training and technique to choreographic

process, music, performance style, and materials. There was no

single prevailing aesthetic in the group; rather, an effort was made

to preserve an ambiance of diversity and freedom. This attitude

gave rise to certain themes and styles: an attention to choreographic

? 1982 by Sally Banes

167

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168 DANCE CHRONICLE

process and the use of methods that metaphoricallystood for

democracy;the use of languageas an integralpart of the dance;

the use of "natural,"or ordinary,movements;dancesabcoutdance.

The first concert produced by the Judson Dance Theatre, "A

Concertof Dance[# 1]," waspresentedon July 6, 1962, at Judson

MemorialChurch.

In the springof 1962, the membersof Robert Dunn's

choreographyclass,givenat the MerceCunninghamstudio, decided

to put on a public concert of works they had been showingto

each other in class. At the end of the previousyear'scoursethere

had been a showingof dancesfor friendsat Cunningham'sstudio

in the LivingTheatre building at Fourteenth Street and Sixth

Avenue. By the end of the secondyear of the coursethe classwas

largerand the studentsmore ambitious. "Therewas a body of work

whichit was called a shameto waste withoutat least a publicshow-

ing, and Judson was asked and they were agreeable. But it was

intendedas a one-shotconcert,"John HerbertMcDowellremembers.

"Wedecided to put on the concertjust for the adventureof it,"

StevePaxtonadds. "Goingout and doingsomethingelsewhere. The

LivingTheatrewas too small."

YvonneRainer,who had seen the first JudsonPoets'Theatre

productionin the choirloft of JudsonMemorialChurch,suggested

that the classlook into holdingthe concertthere. Paxtonmet with

Al Carmines,the ministerin chargeof the church'sartsprogram,and

set up a date for an audition. On the appointeddate Paxton, Rainer,

Ruth Emerson,and perhapsRobertand JudithDunnwent to the

church,wherePaxton, Rainer,and Emersondanced. Rainerdanced

Three Satie Spoons; Emerson,her Timepiece;and Paxton may

haveperformedTransit.* Paxton'smemoryof the auditionis that

"it was a pretty weak showing. But they said, 'Fine."'2 Emerson,

who thinksthat much of the impetusin planningthe concertcame

from Rainer,who wasreadyto show her accumulatedwork,recalls:

*The "perhaps" and "may have" suggest some of the problems in reconstructing

events nearly twenty years later. There will be a number of places in this

account wherepeople's memoriesdiffer on a particularpoint, and there is now

no way to arrive at "the truth."

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 169

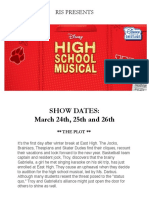

A CONC

OF DANCE

BILL DAVIS, JUDITH DUNN, ROBERTDUNN, RUTHEMERSON,SALLY GROSS, ALEX HAY,

DEBORAHHAY, FRED HERKO, DAVID GORDON,GRETCHEN MACLANE,JOHN HERBERTMCDOWELL,

STEVE PAXTON, RUDYPEREZ, YVONNERAINER, CHARLESROTMIL, CAROLSCOTHORN,

ELAINE SUMMERS,JENNIFER TIPTON

JUDSON MEMORIALCHURCH

55 WASHINGTONSQUARE SOUTH

FRIDAY, 6 JULY 1962, 8: 0 P.M.

The flyer designed by Steve Paxon for "A Concert of Dance," courtesy of

William Davis.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

170 DANCECHRONICLE

Steve and Yvonne and I went down one very hot evening, and I think I

was asked just because I was around. I remember having the feeling

that Al wondered if we'd take all our clothes off or do something ter-

rible. We did a couple of pieces. We came prepared to be really serious

and to show him how we worked. I don't even know if he saw all our

pieces. After ten minutes he said, "Oh, this is wonderful, this is great.

No problem." And we all started laughing.3

JudsonMemorialChurch,an architecturallyeclectic building

at 55 WashingtonSquareSouth, at the cornerof ThompsonStreet,

was designedby StanfordWhitein 1892. Its stained-glasswindows

were designedby John LaFarge,and its baptistrywas built by

HerbertAdamsfromplansby AugustusSt. Gaudens.The church

itself was built by EdwardJudson in memory of his father,

AdoniramJudson,who went to Burmain 1811 as one of the first

Americanmissionaries. The church, dually affiliated with the

AmericanBaptistChurchand the United Churchof Christ,was a

basefor laborunion organizingin the 1930s and for the civil rights

movement, school integrationactivities, and drug addiction re-

habilitationprogramsin the 1960s. In 1961 the parishplayedan

activerole in overturninga ban on folk-singingin WashingtonSquare

park-after a year of protestsand sit-ins-and in the sameyear the

chief minister,HowardMoody, was elected head of the Village

IndependentDemocrats.4

After WorldWarII, when many of the church'smembers

movedout of the city, RobertSpike,ministerfrom 1948 to 1955,

startedan artsprogram,partlyout of personalinclinationand partly

to stimulatethe life of the church. Concertsand playsweregiven

and paintingsexhibited. ThenMoody,who came to the churchin

1956, organizedthe JudsonGallery,which showed works by Pop

artistsJim Dine, Tom Wesselman,Daniel Spoerri,Red Grooms,

and ClaesOldenburgas earlyas 1959. The "JudsonGroup"put on

a programof Happenings,Ray GunSpex, in early 1960; and later

that year Dine presentedhis Apple Shrine, an Environment. A

group called the Judson Studio PlayersperformedFaust in the

sanctuaryof the churchin 1959.5

In 1960, when Moody decided to start a residenttheatre

group the church,he hiredAl Carmines,who hadjust graduated

in

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 171

from Union TheologicalSeminary,to coordinatethe arts program

and organizethe JudsonPoets' Theatre. Whileat the seminary,

Carmineshad gone to partiesfor divinitystudentsat Judson;he also

remembershavingattendedan earlyAllanKaprowHappeningthere.

WhenCarminesheardthat therewas an openingfor someoneto run

the artsprogramat the church,he appliedfor the position. Whenhe

becameassociateminister-on a part-timebasis for the first two

years, while he earneda master'sdegree-Carminescontinuedthe

churchpolicy of aidingas manyartistsas possibleand supporting

the avant-garde without censorship.6

The first productionat the Judson Poets' Theatre, on

November18, 1961, was a doublebill of one-actplays: Apollinaire's

The Breasts of Tiresias and Joel Oppenheimer's The GreatAmerican

Desert. About two weekslater,on December3, Carminesorganized

a "Hallof Issues"at the JudsonGallery,to whichthe publicwas

invitedto contributeartworksand polemics. Duringthe 1961-62

season,JudsonPoets'Theatrepresentedthreemore programsof one-

act plays (openingin January,March,and May),and in MayPeter

Schumanngavea maskeddance/play,Totentanz,with the Alchemy

Players. In the summerof 1962 Carminesbeganwritingmusicbased

on popularformsfor the JudsonPoets' Theatre,startingwith George

Dennison'sVaudevilleSkit.7 Carmines'sapproachto makingtheatre

in the churchwas,he admitted,unconventionalfor a minister.

When I started the theatre in 1961 with the help of Robert Nichols,

who's an architect and playwright, we had two principles. One, not to

do religious drama. Two, no censoring after acceptance.... [The fact

that our plays are performed in] a church liberates me more than any

other place would. I've discovered for myself that God doesn't dis-

appear when you don't talk about him.

Like a lot of ministers, the real world was not part of my life.

Ministers are often preoccupied with themselves. The theatre broke

it all open for me. A source of revelation.8

Carminesremembersthat when the dancersapproachedhim

to ask whetherthey could put on a concertin the church,"I was

scaredof the kind of dancethey did. I wasused to ballet,maybe

MarthaGraham. I hadn't seen MerceCunningham.I said they'd

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

172 DANCECHRONICLE

have to give their first three concertsin the gymnasium,and the

board of the churchwould have to decide whetherit was proper

to do it in the sanctuary."9

The concert was plannedfor July 6, 1962. Accordingto

Rainer,"the selection of the programhad been hammeredout at

numerousgab sessions,with Bob Dunn as the cool-headedprow of

a sometimesoverheatedship. He was responsiblefor the organiza-

tion of the program."Paxtonremembersthat "it was largelyreasons

of necessity that determinedwhat had to follow what: who had

time to be wherewhen, who neededto be free at a certaintime so

they could change. Certainthingsweren'tpossible." He also recalls

that "Dunnmadethe orderof the dances,includingsome that were

shown with each other, which was a popularidea at that time:

'Let's havechocolateand strawberryat the sametime."'10

ElaineSummersrecalls:

Steve and Yvonne and Bob and Judy said, "Let's do a concert and

everybodycan pick one work of their own, or two, and it can be any-

thing you want. Makeyour own decision about what you're going to

present,and let's do a concert in July. It'll be hot, and there won't

be anyone there, and we'll just have a wonderfultime." And then we

all did whateverit was we had to do.

Everyonein the group was extremely responsible. Everybody

had their chores to do, and everybodydid them. And lo and behold,

we had this concert. And we had so much materialit startedat eight

and went until midnight. It was hot in there-ninety degrees-and we

were totally amazedbecauseso many people came. It was absolutely

crushed!l

Steve Paxton and Fred Herkoformed the publicity com-

mittee. Paxton designedthe flyer, which is plain, clear, and also

witty in its hint of repetitionandreversal.Herkowrote the press

release,dated June 22, whichexplainedthat the "youngprofessional

dancers"involvedin "A Concertof Dance"used a varietyof choreo-

graphictechniques. The participantswerenamed: Bill Davis,Judith

Dunn, Robert Dunn, Ruth Emerson,DeborahHay, Fred Herko,

RichardGoldberg,DavidGordon,GretchenMaclane[sic], John

HerbertMcDowell,StevePaxton,Rudy Perez,YvonneRainer,Carol

Scothorn, Elaine Summers,JenniferTipton. This release lists

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 173

choreographersand performerstogether as participants,without

settingup a hierarchy. "Indeterminacy,rulesspecifyingsituations,

improvisations,spontaneous determination,and various other

means"were named as choreographicstrategies,and a concluding

paragraphstated that the event would show a diversityof work,

and that the concert would "be of interest as it signalizes[sic] a

new concernon the partof the youngerdancersto exploredance

with the concernsand responsibilitiesof the choreographer as well

as those of the performer."An abbreviatedversionof this notice,

consistingof the firstparagraphand the namesof all the participants,

appearedin the VillageVoiceon June 28. The flyer was sent to

names on the churchmailinglist, as well as the dancers'friends

and acquaintances.12

The programfor the concert lists the followingcredits:

lightingdesign,CarolScothorn;lightingoperation,Alex Hay;musical

direction,RobertDunnandJohn HerbertMcDowell;costumecon-

sultant,Ruth Emerson;stagemanager,JudithDunn;film projector

operation,EugeneFreeman[sic]; advisory,Judith Dunn, Robert

Dunn.13

DespiteCarmines'originalplan, the concertwas givenin the

sanctuaryof the church,one flightup from the street-levelentrance

on WashingtonSquare. A curtainwashung from the edge of the

choirloft, at the oppositeend of the room from the altar,and served

as a dividerbetween the lobby-entranceand the performingspace

in the sanctuaryproper. It also servedas a backdropfor the "stage,"

which was simplythe spacein front of the curtain. An architectural

rhythmfor this settingwasprovidedby the four columnssupporting

the loft. The audiencewalkedin throughthe lobby, acrossthe bare

space,and to their seats. At that time the churchstill held tradi-

tional "highBaptist"services. Therewas a pulpit and a largecross

at the altar,at the south end of the sanctuary,and the congregation

sat in movablepews facingthe altar. The Poets'Theatreperformed

in the large choir loft, not on the sanctuaryfloor. The dancers

alteredthe arrangementof the sanctuaryby movingthe pews around

and puttingthem in front of the altar,facingnorth, and alongthe

sidesof the room, clearingthe rest of the spacefor the dancing.14

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

174 DANCECHRONICLE

"A Concertof Dance"was arrangedwith a slightly asym-

metricalbalanceof solo and group dances,solos by men and by

women, danceswith and without music, with live and recorded

music, talkingand singing,slow and fast and variabletempi,

simple and complex choreographicstructures,plain and fancy

costumes. The twenty-threeitems on the programwere divided

into fifteen units. Dance numberone was actuallya film, and it

was billedundera musicalterm: Overture.So from the moment

the concertstarted,the irreverenttrespassingof artisticboundaries

was present. A group work followed, then a solo by a woman,

then three solos by men, then anothergroupwork. In mirror

sequence,the next six dancesweregroup,male solo, threefemale

solos, anothergroup. The only duet was performedduringthe

intermission. Followingthe intermission,there were nine more

dances: group,two male solos, group,two femalesolos, male solo,

femalesolo, group. Two pieces of musicby ErikSatiewereheard

as accompanimentsin the firsthalf of the program(perhapsthe same

piece), but in betweenthem were two dancesin silencethat them-

selvessandwicheda danceto musicby Marc-AntoineCharpentier.

CartridgeMusic by John Cage,which was also used for two dif-

ferentdances,wasplayedonly once, as the dancesweredone either

simultaneouslyor overlappingone another.s1

Severalaspectsof this concertwouldlaterbecomeessential

featuresof the JudsonDanceTheatre,as this groupof choreographers

soon came to call itself: the democraticspiritof the enterprise;a

joyous defianceof rules, both choreographicand social;a refusal

to capitulateto the requirementsof "communication"and "mean-

ing" that were generallyregardedas the intention of even avant-

gardetheatre; a radicalquestioning,at times throughseriousanalysis

and at times throughsatire,of what constitutethe basicmaterials

and traditionsof dance.

As the audienceenteredthe sanctuaryat 8:15 on the evening

of July 6, a film was beingprojected. McDowellrecalls:

[The film] was Bob Dunn's doing and was beautiful. The dance con-

cert was announced to start at 8:30. The audience was admitted at

8:15, and they went upstairs into the sanctuary to find that in order

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSON DANCE THEATRE 175

to get to their seats they had to walk acrossa movie that was going on.

It was embarrassing,and Bob's whole point was to discombobulate

them, to quash their expectations. This movie consisted of some

chance-editedfootage by Elaine [Summers] and test footage that I

made, all of which was blue-y.... And W. C. Fields in TheBankDick.

And we went on exactly, preciselyfor fifteen minutes. The last

sequencein the film was the final chase scene from TheBankDick.

And then there was a marveloussegue between the unexpected film

and the dance. The first dance, which was by Ruth Emerson,started

on the dot of 8:30. As the movie wasjust about to go off, the six or

so people involvedcame out, the movie sort of dissolvedinto the dance,

and as the stage lights came up the dancerswere already on stage

and the dancehad alreadystarted.16

The authors of Overtureare listed as W. C. Fields, Eugene Freeman

[sic], John Herbert McDowell, Mark Sagers, and Elaine Summers.

Summers was then learning filmmaking from Gene Friedman, an

assistant camerman in commercial television and cinema who was

also a friend of McDowell's. Summers remembers being so stimu-

lated by the chance methods Dunn taught that she suggested making

a chance movie. Friedman had been giving Summers assignments

that, though they were traditional problems for beginning film-

makers, bear a striking similarity to some of Dunn's assignments

in the choreography class.

He would say, "Takea three-minutereel of film and do a complete

story nonverballywith it. And no cutting, you have to do it in the

camera." And then he would want one that had zooms.

So I had a lot of scrapmovies, and Gene was contributingnot

only his gurushipbut also films-tail ends of movies, called short

ends, from the TV stations where he was working. And John had

some W. C. Fields movies.

John, Gene, and I got together and used a chancesystem from the

telephone book. Wetook all the film stripsand we rolled them up

and we put them in a big paperbag. They had numberson them, like

one foot, two feet, three feet. We'dget a numberfrom the telephone

book, like 234-5654, and we'd have to put the film strips together

in that sequence.

I remembersaying, "Thiscertainlybringsout the stubbornin one,

becauseI don't want to put a two-foot strip here, I want to use a six-

foot one." And of course, that was one of the exciting thingsabout the

chancemethod. You suddenlyrealizethat you have a lot of opinions.17

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A CONCERTOF DANCE

Judson Memorial Church

55 Washington Square South

Friday, 6 July, 8:30 P.M.

1. OVERTURE:W. C. Fields, Eugene Freeman, John Herbert

McDowell, Mark Sagers, Elaine Summers

2. Ruth Emerson: NARRATIVE

(performers: Judith Dunn, John Herbert McDowell, Steve

Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Elaine Summers)

Ruth Emerson; TIMEPIECE

3. Fred Herkb: ONCEOR TWICEA WEEKI PUTON SNEAKERS TO

GOUPTOWN

(music: Erik Satie; pianist: Robert Dunn; costume:

Remy Charlip)

Steve Paxton: TRANSIT

John Herbert McDowell: FEBRUARY FUNAT BUCHAREST

(music: Marc-Antoine Charpentier)

k. Elaine Summers: INSTANTCHANCE

(performers: Ruth Emerson Deborah Hay, Fred Herko,

Gretchen MacLane, Steve Paxton, John

Herbert McDowell, Elaine Summers)

5. David Gordon: HELEN'SDANCE

(music: Erik Satie; pianist, Robert Dunn)

6. Deborah Hay: 5 THINGS

Gretchen MacLane: QUBIC

Deborah Hay: RAIN FUR

7. Yvonne Rainer: DANCEFOR 3 PEOPLEAND6 ABMS

(performers: William Davis, Judith Dunn, Yvonne Rainer)

8. INTERMISSION: (coffee will be served in the lounge)

Yvonne Rainer: DIVERTISSEMENT

(performers: William Davis, Yvonne Rainer)

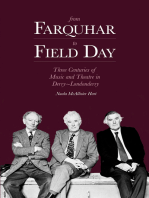

The originalprogramfor "A Concertof Dance,"courtesyof

WilliamDavis.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSON DANCE THEATRE 177

9. Elaine Sumers; THE DAILY WAKE

(structure realized by the following performers;

Ruth Emerson, Sally Gross John Herbert McDowell,

Rudy Perez Carol Scothorn)

(music: Robert Dunn, John Herbert McDowell,

Elaine Summers, Arthur Williams)

10. David Gordon; MANNEQUIN DANCE

(music: James Waring; costume; Barbara Kastle)

Fred Herk9-Cecil Taylor; LIKE MOSTPEOPLE--for Soren

(costume: Remy Charlip)

11. Steve Paxton- PROXY

(performers; Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Jennifer

Tipton)

12. John Cage: MUSIC

CARTRIDGE

Carol Scothorn ISOLATIONS

Ruth Emerson. SHOULDER

13. William Davis: CRAYON

(music The Volumes, Dee Clark, The Shells)

14. Yvonne Rainer: ORDINARYDANCE

15. Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Charles Rotmil: RAFLADAN

Lighting design: Carol Scothorn; operator: Alex Hay

Musical direction; Robert Dunn, John Herbert McDowell

Costume onsultant: Ruth Emerson

Stage manager; Judith Dunn

Film operator; Eugene Freeman

Publicity: Fred Herko, Steve Paxton

Advisory: Judith Dunn, Robert Dunn

(Thanks are due to the public spirit of Judson

Memorial Church for the use of their facilities

and for coffee; further thanks to the Merry-Go-

Rounders, to Thomas Skelton, and to Michael Malce,

for vital assistance.)

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

178 DANCECHRONICLE

Accordingto McDowell,some of the segmentswere upside-down

and backwards.18

Allen Hughes,the dance critic for the New York Times,

called Overture"a movingpicture 'assemblage"'and wrote in his

reviewof the concert:

The overture was, perhaps, the key to the success of the evening, for

through its random juxtaposition of unrelated subjects-children play-

ing, trucks parked under the West Side Highway, Mr. Fields, and so

on-the audience was quickly transported out of the everyday world

where events are supposed to be governed by logic, even if they are

not.19

Item numbertwo consistedof two dancesby Ruth Emerson.

JudithDunn,John HerbertMcDowell,StevePaxton,YvonneRainer,

and Elaine Summersdancedin Narrative,a three-sectiondance.

Eachdancerwas givena scorethat indicatedwalkingpatterns,focus,

and tempo, and also cues for action based on the other dancers'

actions. The instructionswere not dramaticor psychologically

descriptive;they referredto abstractmovementsand individual

focus ratherthan interaction. For instance,directionsto dancerB

(Paxton)includethe directive"Takegreatcareneverto focus on G

[Rainer] or to directyour movementat her." Threeof the dancers

walkedalong geometricalpaths duringpart one: Paxton along

diagonals,Dunn along a rectangle,and Summersalong a circle;

McDowellwalked backwardsat random,and Rainerwalkedside-

ways at random. The focus for each dancerwas quite specific,and

eachhad to cue his or her tempo to those of the other dancers. In

the secondsection Dunnsat with focus down, Paxtondid a move-

ment pattern(two quickdiagonalextensionsof the foot and arm,

and a turningarmgesturein plie, with focus up) seventimes, and

Rainerdid anothermovementpattern(fouette with arms,break

at elbow and relax), four times. (The scores for the other two

dancersin the second section have been lost.) Part three was an

orchestrationof patternedexits, chiefly along diagonallines.20

Narrativewas not taught to the dancersor written with

expressiveovertonesin psychologicalterms,but Emersonsays that

she was tryingto makeit a dramaticdance-

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 179

Dramaticin the sense that by placingpeople in the space and by

turningthem in different directions, I could show somethingabout

relationships. Therewas little that happened,except people changed

their [spatialand temporal] relationshipsto one another. It had very

little tension, which is what I obviouslywould have liked to achieve.

I didn't feel it was a brilliantsuccess. I think I did not know very

much about groups of people and was finding out more about my

body and how to construct material for me. That was more

productive.21

The firstlive danceon the program,then, wasa new twist

on an old modem-dancetheme. The title suggestsa literalmeaning,

of the sort that the older generationof modem dancersalways

offeredan audience. And moder-dance choreographers often used

diagonal lines to connote dramatictensions. But Emerson's

Narrativewas a dramawithout a narrative,withoutspecificor co-

herentsymbolicmeaning.

The next dance was Emerson'ssolo Timepiece. It was

anotherdancestructuredby chance,basedon a chartthat extended

the categoriesshe had workedwith in earlierdances. The charthad

columnsfor quality(percussiveor sustained);timing(on a scalefrom

one to six, rangingfrom very slow to very fast); time (units of

fifteen seconds,multipliedby factorsrangingfrom one to six);

movements(five possibilities: "redbag,untying;turn,jump,jump;

hands,head, plie; walkingforwardside backside side;heronleg to

floor");space time (ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, or stillness);

space (five areasof the stage plus offstage);front (directionfor

the facingof the body, with four squaredirections,four diagonals,

and one wild choice, marked"?");andhigh,low, or mediumlevels

in space. The qualitieshavingto do with movementand timingwere

put together,alongthe graphof absolutetime, separatelyfromthe

qualitiesdealingwith space. Thuschangesin area,facing,andlevel

in spacemightoccur duringa singlemovementphrase. Timepiece

startedout with stillness. "To my utterhorror,"Emersonrecalls,

"I had to get over the fact that I could start a piece with forty

secondsof stillness. One of the reasonsI liked the piece was that I

learnedI could do that."22

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

180 DANCECHRONICLE

Timepiece,with its componentstightly governedby various

independenttemporalcontrols,punninglyrefersto a stopwatchor

clock, the legendaryaccoutermentof both John Cageand Robert

Dunn. It also seemsan appropriatestep, in termsof the increasingly

upset expectationsof the audience,in instructingthe spectator.

After the first dance,Narrative,made clear what this new work

would not be, the second dance presenteda paradigmaticchance

dance,an exampleof what much of the new workwould be.

Paxton remembersEmerson'sdancing in Timepiece as

"boundy"-"Very long-limbed. Not particularlyarticulate. A lot

of large shapes, big sweeps.... "We talked a lot about her per-

formance,becauseshe looked very glazed when she performed.

I remembertrying to encourageher to be less glazed. And I re-

memberJudith Dunn looking disapproving,perhapsbecausethat's

how she [Dunn] looked when she performed. But somehowthat

was appropriateto her."23 The question of the dancer'sper-

formingpresencewas one of the issues this groupwas trying to

understandand resolvein a way consonantwith their emerging

styles. "Wedidn'twant to emote,"Paxtonexplains. "Onthe other

hand, the glazed look was obviously becoming or alreadyhad

become such a cliche."24

Unit numberthree on the programcomprisedthree solos

by men, whichmay haveindicatedthat they wereperformedsimul-

taneously,or else that they wereperformedin close sequence,with-

out a break. Thesesolos wereHerko'sOnceor Twicea WeekI Put

on Sneakers to Go Uptown; Paxton's Transit; and McDowell's

February Fun at Bucharest.

Jill Johnston,writingin the VillageVoice,describedOnceor

Twicea Week... (whichhad musicby ErikSatieplayedby pianist

RobertDunn,and a costumedesignedby Remy Charlip): "Herko

did a barefootSuzie-Qin a tassel-veilhead-dress,movingaroundthe

big open performingarea... in a semi-circle,doingonly the bare-

foot Suzie-Qwith sometimesa lazy armsnakingup and collapsing

down." He performed"withno alternationof pace or accent."25

Allen Hughesdevotedone-fifthof his reviewof the concertin the

Timesto this dance.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 181

Fred Herkocame out dressedin multicoloredbath or beach robe with

a veil of lightweightmetal chainscoveringhis head and face ... One's

attention was rivetedto his dance, which was no more than a kind of

unvariedshufflingmovementaroundthe floor to the accompaniment

of a piano piece by ErikSatie. (Satie, incidentally,would have loved

it.)

This was the Sneakersdance, but Mr.Herkowas barefoot all the

while.26

Remy Charlipremembersthat he made a cap based on an

Africandesignfor Herko,with stringsof beads endingin small

shellsthat hung down overhis face andhead, expresslyto emphasize,

in sound and movement,the swayingthat was the dance'smotif.

Charlipalso thinks that the title was a kind of ironic reverse

snobbishness:if the bohemiansand avant-gardists downtowndanced

proudly in bare feet, then to put on sneakerswas to dressup, a

humorousconcessionto "aboveFourteenthStreet."27 Like the Pop

artiststhen workingin GreenwichVillage,Herkowasusingmaterial

frompopularcultureas the subjectof his work,for what Johnston

calleda Suzie-Qmightalso havebeen describedas the Twist,just

then enjoyingan enormousvoguein New Yorkdanceclubs.

Herkowas friendlywith Andy Warhol,whomhe had met at

the San Remo Coffee Shop at Bleeckerand MacDougalstreetsin

the Village. WarholremembersHerko(who committedsuicidein

1964) as "a very intense, handsomeguy in his twenties . . . who

conceivedof everythingin termsof dance." Warholnotes:

He could do so many things well, but he couldn't supporthimself on

his dancingor any of his other talents. He was brilliantbut not

disciplined-the exact type of person I would become involved with

over and over and over againduringthe sixties.... Freddy eventually

just burnedhimself out with amphetamine;his talent was too much

for his temperament. At the end of '64 he choreographedhis own

death and dancedout a window on CorneliaStreet.28

Paxtonwasnot impressedby Herko'sworkin generalduring

the JudsonDanceTheatreworkshopsandperformance.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

182 DANCECHRONICLE

It seemed very campy and self-conscious, which wasn't at all my

interest. As I rememberhe was a collagistwith an archperformance

manner. You would get ballet movement,none of it very high-energy.

Maybe a few jetes every now and then. As a dancerhis real forte

was some very, very elegantlines. But in termsof actualmovement,

transitionsfrom one well-defined place to another, he did it rather

nervously. Holdinga position was more what he did than movingfrom

place to place.29

Allen Hugheswas more enthusiasticabout Herko'sstyle, as both

dancerand choreographer.

His dances were architecturally organized. He didn't just go willy-

nilly from here to there. He always had a sense of theatrical structure.

Herko was a performer with charisma. He may not have been a great

choreographer; I'm only saying that he vitalized that movement, he

gave it a vividness that many of the others did not. Herko was the

brightest performing star of all. He was a happy exhibitionist, which

makes theatre. He wouldn't allow himself to go too far off into inner-

somethings, because he never wanted to lose his public.30

Al Carmines,who workedmore closely with Herkoin the Judson

Poets' Theatre,recallsthat Herko'swork "alwaysincludedhumor

and pathos and high-classcamp. He was an unusualactor, and

adudiencesadoredhim. He learnedto be totally accessibleto an

audience."31

Steve Paxton's Transit, following Once or Twice a Week ...,

was a solo that presenteda spectrumof movementstyles, from

classicaldance (ballet) to "markeddance"(technicalmovement

performedwithout the high energy usually expended in per-

formance)to pedestrianmovement. It also presenteda spectrumof

speeds, from runningto slow motion. Paxton would performa

classicalballet phrase,then repeatit in a markedversion,run at

differentspeeds, and stand in tense or relaxedpositions. "It was

just takingitems and playingtheirscales,"32he recollects. Transit

was an analysisby dissection of ballet movement, which is

recognizableon stageby one of its essentialcomponents: a taut,

chargedbody.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 183

Transit,whichPaxtonthinksof as a collage,wasmadespe-

cificallyfor the concertat the Judson,not for RobertDunn'sclass.

It was eightminuteslong. Paxtonperformedthe dancebarefootin

blackfootless tightsandleotard. Therewas no soundaccompani-

ment. Paxtonrehearsedthe dancefor a month;most of the time

was spentperfectingthe balletphrase,whichwas "a pet phraseof

MargaretCraske's.That'swhy I wantedit." Paxtonhad learnedthe

phrasesecondhandfromCarolynBrown,who regularlytook ballet

class at Craske'sstudio in the MetropolitanOperaHouse, as did

severalothermembersof the Cunninghamcompany. Paxtonwent

to Craskeonly occasionally.33

John HerbertMcDowellwas among the performersand

choreographers in the Judsonconcert with the least formaldance

training. He was a composer,trainedat ColumbiaUniversity,who

had begun writingmusic for dancein the early 1950s. Among

others, he had workedwith RichardEnglund,JamesWaring,Paul

Taylor, and Aileen Passloff. McDowellhad met Robert Dunn in

1961, when he hired Dunn to play the piano for Taylor'sInsects

and Heroes. McDowellfirst took movementcoursesfor theatre

from Alec Rubin at the MasterInstituteand then joined Dunn's

choreographycourse.34

Jill Johnston wrote approvinglyof McDowell'sFebruary

Fun at Bucharest

John Herbert McDowell is a composer. He has no dance training....

Having no ties or tensions arising from a training and having an in-

ordinate sense of fun, McDowell distinguishes himself as a "natural"-

not a natural dancer (although you could think of it that way if you're

not too set in your idea of what dancing is): I mean a natural person

going about the business at hand, which in this case consisted of a few

zany actions performed in a red sock and a yellow sweater.35

Dianedi Primadescribedthe danceas "JohnMcDowellin a red sock,

leapingaboutlike a dementedpixie." McDowellhimselfremembers

that he stood on his headin front of a mirrorandpulledhis hair

out. But these "zanyactions"wereset againstthe baroqueweight

of music by Marc-AntoineCharpentier.McDowellsays that the

music had nothing to do with the dancing;he simplyhad to use

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

184 DANCE CHRONICLE

other people's music to accompany his own dances. Perhaps

McDowell's choice was also governed by an ironic tribute to a

special alliance between theatrical dance and religion that preceded

Judson Church and its Dance Theatre: Charpentierwas, after all,

one of the most important composers of Louis XIV's court-re-

nowned for its opera-ballets-where he composed both theatrical

and religious music.36

The dance listed as item number four on the program was

Elaine Summers' Instant Chance. Summers used high, numbered

Styrofoam blocks, carved into different shapes and painted dif-

ferent colors on different surfaces, to cue movement for the dancers

(Ruth Emerson, Deborah Hay, Fred Herko, Gretchen MacLane,

Steve Paxton, John Herbert McDowell, and Summers herself). The

dancers would throw the blocks up in the air. Each dancer had a

separate movement choice in response to the three different factors

that fell top up. The shape dictated the place or type of movement;

the color told the rate of speed; the number governed the rhythm.

For instance, Emerson's score indicates that for the cone, her move-

ment should be in the air; for the cube, in releve; for the column,

standing; for the sphere, sitting or kneeling; for the oblong, on the

floor. If she saw yellow, she should move very fast; blue, fast;

purple, medium; red, slowly; pink, very slowly. The instructions

for following the cues dictated by the numbers reads: "Repeat

movement, every movement 5 times but the number equals a

rhythm. 1=1 (an insistent pulse), 2=2/4, 3=3/4, 5=5/4." Each

performer was also assigned a color as an identifying mechanism;

Emerson, called Pink, wore a pink leotard.37

Summers says that she called the dance Instant Chance be-

cause she felt that most chance dances used hidden operations:

the moves were determined by chance beforehand, but then the

dance was set and the audience had no way of knowing what method

the choreographer had used. (For instance, Merce Cunningham

has used this technique.) In Instant Chance the overt display of the

chance method was central to the viewing of the dance. The dance

also incorporated improvisation, because Summers gave very broad

parameters for movement choices. Although the choreographer

set up rules for her dancers, how these rules would come to be

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 185

expresseddependedon both the rollingof the "dice"and the im-

mediate decisionsthose circumstancesand instructionsprompted

in the dancers. Summersexplains,"If 'red'and 'one' meantcover

spaceandleap, I didn'tknow how that personwas goingto leap,

or how they weregoingto coverspace." Withthis score, Summers

was also tryingto confrontthe glazedor else overlyexpressivefaces

that plaguedso much of modem dance,and to produceinsteada

look of engagementand intelligentconcentration.The dancealso

promoteda senseof spontaneityand childlikeplay, valuingfreedom

of choice and action.38

In his reviewof the concertin the Times,Hughesexplained

the apparentmechanismof the dance,but he could not explainhis

reactionto it

Six performers appeared to be playing on a beach. They had various

objects, including a ball, that they tossed around like dice, and the

objects were numbered. The numbers that came up on the objects

probably gave the dancers clues as to what they would do next. In

any event, there was movement of all kinds going on steadily, and

for some reason or other, it was interesting much of the time.39

Accordingto DavidGordon,whoseHIelen'sDance wasitem

numberfive on the concert,his piece was one of the weaponshe

used in an ongoingattempt to make Dunn'sclass uncomfortable.

The primary concern of the Dunns was to teach chance proce-

dures, and they rigidly persevered against any chance occurrence that

might alter the course of an evening's schedule. A flick of the long

yellow pad and "let's get on with what we have to do" generally put

an end to spontaneous discussion. The dogmatic approach of the class

often irritated me, and I sought ways to beat the system. Helen's

Dance was made to a piece by Satie as a class assignment. We were

given the options of using the music in various ways. None of these

options included the possibility of ignoring the music, which is what I

chose to do. The apartment that I lived in then was a three-room rail-

road flat, and I had no studio space available to me so I made a long

narrow piece that moved through the three rooms. I performed it in

about twelve feet of space at the Judson. Helen's Dance was a series

of twenty-odd activities performed in a straight line, one after another,

including some gestural dance material. Miming planting a flower was

one of the things.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

t.

.I

S***.6

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 187

The costume, I rememberlater, had black-and-whitestripedtights

and a black-and-whitegeometricallypatternedtop trimmed with jet

fringe. At the JudsonperformanceI probablywore black tights and a

black tank top leotard.... The piece was namedfor a friend who died

of cancer at that time, and it became inexorably confused with her

death in my mind until I realizedthat I was performingit in a terribly

sentimentalfashion, and I neverdid it again.40

LikeHerko,like the choreographerSimoneForti, who had been an

early memberof the Dunn choreographyclass,like the composer

La MonteYoung,and perhapseven like Satiein a way that he never

intended,Gordonchose to amplifyconcentrationon a singlephe-

nomenon-anotherway to get closerto the "facts"of things,to list

thingsis an elementalform.

Numbersix on the programcontainedthree solos: Deborah

Hayin her 5 Things,GretchenMacLanein her Qubic,and Hay again,

this time in RainFur. All threedancesweredone in silence,and

it may be that they overlappedin some way, as Paxtonsuggested

about the arrangementof the programas a whole. (Neitherchore-

ographercan remember,however,whetherthis was the case or not.)

Hay,one of the youngestmembersof the group,had grown

up in Brooklyn,learningdancingfirst with her mother and then

at the Henry Street Playhouse. After a summerat Connecticut

College,whereshe becamefascinatedby MerceCunningham's work,

she enrolledin Dunn'schoreographyclass with her husband,the

painterAlex Hay. Hay destroyedher dancescoresin 1971, and she

remembersvery little about her early dancesat the Judson. She

thinks that in Rain Fur she reclinedon the floor in front of the

audience,with her backto them, "in a very familiar,painterlylying

posture." She then rolled over to the other side and faced the

audience. Perhapsthis is the dancethat Rainerrecallsfrom the first

concertin whichHay wore a skirtmadeof smallhoops that hobbled

her, severely restrictingher movement possibilities.41

Like Hay, Gretchen MacLane, who had grown up in Chicago

studyingballet, tap, and characterdancing,discoveredCunningham

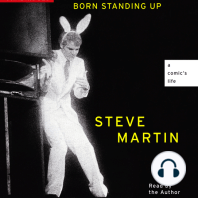

David Gordin in Manequin Dance, photographed in 1966.

? 1966 by Peter Moore.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188 DANCECHRONICLE

duringa summerat ConnecticutCollege. She remembersseeing

Cunninghamand CarolynBrowndancingNight Wandering, and for

the first time being moved by modem dance. About her Qubic

(pronounced"cubic")she remembersonly that it was made for

Dunn'sclass,and that it must have been in responseto an assignment

about space, because she named it after the three-dimensional

tic-tac-toegamethen popular.42Paxtonremembersthat in Dunn's

class,MacLanewas "somebodywho had a gift for beingreallydroll

and constantlyfoughtit." MacLanerememberswatchingPaxton's

work and being "boredout of my mind." "But," she adds, "it

wasn'tbad beingboredin those days."43

The twelfth dancein the concert(item numbersevenon the

printedprogram)was Yvonne Rainer'sindeterminateDance for 3

Peopleand 6 Arms. It had first been performedon the March24

programat the MaidmanPlayhouseduringthe New York Poets'

Theatrefestival of 1962. Rainerdescribesthe dance as "a trio

consistingof an improvisedsequenceof predeterminedactivities."

It was first dancedby Rainer,WilliamDavis,and TrishaBrown;at

the Judson concert Judith Dunn replacedBrown, who was in

Californiafor the summer.44

The movementoptions, as mightbe expectedfrom the title,

emphasizedthe dominanceof the arms,althoughthe whole body

was set in motion. The armsoften led, workedindependentlyof,

or wereset againstthe rest of the body'smotion. In a sensethe

dancewas a probinganalysisof the functionof the balleticport de

bras. The choicesthat the dancerscould makeincludedten "move-

ments,"three "actions,"and two "positions." At the beginningof

the dance,the threeperformersstood upstagefor a moment,then

all threedid the third "movement":a turned-inattitude with spread-

eaglearmsthat pulledthe body around,the whole action traveling

downstage. For the next fifteen minutes,the performersfreely

madetheirown choicesfrom the gamutsuppliedby Rainer,except

for one restriction: when anyone startedone of the "actions"-

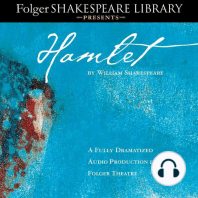

Yvonne Rainer in Ordinary Dance as performed in February

1963 at Judson Hall. Photograph by V. Sladon.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Pefln18891PI

611r mer

Iee w

--e

,

?-

c i? 8,

Btgjd( '?

i.cY

.iL?.: ..?:?

*;i. ;?-;;

.i?;;?- r

I IPI 3 ? ;::?.?

;i-

i::-???;::

.* : ;:)i.i?.??;?.

??.??i : : ?:- ??"':

;i.

?:-

i:' s ?:? i?-.

: :"?? i ? : ?-;?:?:?.

f-?'' :;

?il ? i 'rr.;???:

iir??: ??..: ?:

ii :

...i

:: ?i

?:?

'?'?.'' ? r F : ?? ?. ??

?:? :

?I' '? ' "?::?.'?. ci

?:

:.:'?? '* I ??

?. ??: "

??:

"

: :':.

?5:':

:

"'

i

::';':::

?r?

.?

i i?

: ' '

.?:jr?:

:?;???

::?

i.?I' ?

?: ?.: i:?

???..??--i:.*-?:'P

.'?*rmr*!jl''..? ':? '?.?".???

????.????'IP.r,???

?;?;.;???i"l'....'...'""**..'......

:?? i :i??l

:'C-:;;*C?.r?,4..*

? .$:

i: iI;. . ;;?"?'-:,

?'

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

190 DANCE CHRONICLE

*

I _ ^' ii.

^ i' ** X

R^

rI I

'" * Yvonne

F1'963 aJus

*

Rainer in Orinr

Hal. P

in.:

g

Dac

by

as perfonned

...

V. Sladon.

**WW~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

February

!I ? "1'^~~~~~~~~

^B ^^H~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~?

j~ ~~ ~~?:ci ?, s

i

_:? :: . ;?

I ~~~~~~~~

.'^;. ~ .::^-' o' ;*?::.. ^w^HH .

^^

Rainer in Ordina~ryDceapeordinFbay

Yvonne

1963

Judson

at Hall. Photograph by V. Sladon.~~~:

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 191

the one that Rainerdescribesas "'Blam-blam.Blam. Blam-blam,'

accompaniedby flat-footedjumpingabout"-the other two had to

stop what they were doingandjoin in. Rainer'sexaminationof arm

movementsincludeda balleticport de bras,nicknamed"Flapper,"

done with limp arms,while the dancertraveledforwardin a relaxed

alternatingfourth position. In another "movement"the body

engagedin "foot-playwith one hand 'consciously'movingthe other

hand about the body. Handsalternatebeing 'animate'and 'in-

animate."' Another"movement"was a seriesof activitiesincluding

a releve with the right palm glidingup the nose, scratchingthe

arm while walkingin a circle, then throwingthe head back while

bendingthe knees in parallelplie. The arms"swim"or droop,

the handsplacethemselveson the body while the dancerwalksin

plie and squeaks,or the hands clasp the anklesduringbourree

steps, or the hand and head vibratewhile the rest of the body

collapsesinto a squat. The other two "actions,"besidesthe flat-

footed "blam-blam,"were movingthe armsas quickly as possible

and simultaneouslydescendinginto the prone position as slowly

as possible,and rockingfrom side to side while the handsplay a sort

of gamewith the head-trying to claspeach other without the head

noticing. The two "positions"were "ghoul"and "twistwith eye-

ballsup-perched on one leg. Placedeither d.[own] s.[tage] right

or d.s. left."45

After seeingthe firstperformanceof Dancefor 3 Peopleand

6 Arms, at the Maidman,Jill Johnstoncalled it "dazzling"and

announcedthat Rainerhad "arrived"as a choreographer.Maxine

Munt, writingin Show Businessabout the same concert, thought

the dance"redundantand disaffectinglygauche."46

WilliamDavis,who was a memberof MerceCunningham's

company at the time, remembers Dance for 3 People and 6 Arms

as one of his happiestperformingmoments.

I rememberwaitingfor the curtainto go up at the MaidmanTheatre.

I think it was the first time dancerswere waitingfor a curtainto go

up without havingany idea whatsoeverof the shapethe dancewas

going to take.

That kind of thing was being done musically [in the work of Cage

and his colleagues]. But what this reallyresembledwasjazz musician-

ship, more than chance operations,in the sense that we knew the

"themes," but not the "orchestration." We would all be working

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

192 DANCECHRONICLE

for a time when we might, for example, do this, or, seeing what some-

one else was doing, think, "Oh yes, I can connect this to that," or

"They'redoing fine, I'll just let them go at it." It was a sense of shape

takingplace in three people's minds as the dance was going on. It was

wonderfulto perform.47

The demandsof the movementsthemselvesso taxed the

dancers'coordinationthat to be as awareof each other'sactionsas

Davisdescribesrequireda finely tuned sensitivityto the other per-

formers. LogicallyextendingJohnCage'suse of indeterminatemusic

scores-somethingCunninghamhimselfhad not attempted-Rainer

createda dancethat both gavecontrolgenerouslyto the performers

and demanded their utmost concentration, attention, and

intelligence.

Intermission,numberedeight on the program,followed

Dance for 3 People and 6 Arms. The program noted that coffee

would be servedin the lobby. But Raineralso presentedDivertisse-

ment, in the traditionof balletentr'actesin Europeanoperas. Spoof-

ing dancepartnering,Rainerand Davisenteredthe sanctuaryfrom

behindthe curtain,graspingone anotherclumsily. Theirlegs inter-

locked so that they could barelywalk,and then only sideways. They

stumbledacrossthe floor, lurchingthroughthreeor four different

steps, then exited throughthe lobby.48

In a way, Divertissementwas a comment on Rainer'sown

workand the workof her colleaguesas well as a satireon traditional

theatricaldance. ComingdirectlyafterDancefor 3 Peopleand 6

Arms, probablythe most radicaldance on the programin terms

of its structureand movements,Divertissementacknowledgedthat

Dance for 3 People and 6 Arms and the other unconventional dances

on the programwere not devoid of roots in a historicaldance

tradition.

Afterintermissioncame Summers'TheDaily Wake,number

nine on the programand the fourteenthdance. Thiswas a group

piece basedon readingnewspapersas scores. The creditssay that

the "structure[was] realizedby the followingperformers: Ruth

Emerson,Sally Gross,John HerbertMcDowell,Rudy Perez, Carol

Scothom." The musicwas by RobertDunn,John HerbertMcDowell,

Elaine Summers,and ArthurWilliams,a downtown playwright.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSON DANCE THEATRE 193

Summers herself made up a movement sequence inspired by the

scores, then gave the dancers written instructions specifying move-

ment qualities for the three sections of the dance. She also per-

sonally taught them a series of poses taken from photographs in the

newspaper. The dance began in stillness. Then all five dancers

performed individual dances at individual tempos during the first

section of the piece. When they had finished, each assumed the first

pose assigned him or her for section two, until all five had assumed

poses, and the series, including group poses, began. The positions

included the Twist, swimming, an umpire, soldiers, a handshake,

Rockefeller, a bride, graduation, and a Pantino advertisement. In

the third section, each dancer was assigned certain numbered move-

ment phrases, certain actions and qualities to apply to these phrases,

a floor pattern that corresponded graphically to a newspaper layout

design, and a time pattern.49

Summers explains her use of the newspaper as a method for

generating a score:

The Daily Wake was based on the front page of a daily newspaper, the

Daily News. What they have reported is already dead and finished,

so it has a wakelike quality. I took the front page and laid it out on

the floor and used the words in it to structure the dance, and used the

photographs in it so that they progressed on the surface of the page

as if it were a map. If you start analyzing that way, vou get deeper

and deeper. You get more clues for structure, like how many para-

graphs are there? Beginning with The Daily Wake, I became very

interested in using photos as resource material, and other structures

as maps.50

The interest in photographic freeze-framesof movement, which also

informed Paxton's Proxy, signals an analytic concern with the

moment-to-moment process of human movement, almost as if the

choreographers wished to appropriate the filmmaker's ability to

slow down a film and watch it frame by frame. It is also a strategy

for making movement without submitting to personal taste.

Item number ten on the evening's format consisted of David

Gordon's Mannequin Dance and Fred Herko's collaboration with

Cecil Taylor Like Most People-for Soren. According to Gordon,

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

194 DANCE CHRONICLE

MannequinDance was made, in responseto anotherclass assignment,

while standingin a bathtubwaitingfor A-200 to take effect on a bad

case of crabs. In the piece, I turnvery slowly from facing stageright

to diagonallyupstageleft and slowly make my way down to lie on the

floor. That about covers the territorythat a bathtub has to offer.

The piece took about nine minutes to perform, duringwhich I sang

"SecondHandRose" (after Fanny Brice and before BarbraStreisand)

and "Get MarriedShirley,"two songs to which I had become addicted.

It was slow, tedious, concentrated,theatrical,virtuosic, and long.51

After he had begunloweringhimself to the floor, Gordonraised

his hands graduallyuntil they extended out in front of him and

wiggledhis fingersslowly and regularly.The effect was both sooth-

ing andmacabre. Besidesthe singing,musicwas providedby James

Waring,who passedout balloonsto the audienceand askedthem to

blow up the balloonsand to let the air out slowly.52

The reasonthe piece was calledMannequinDance . . . was that I had

had the idea to rent department-storemannequinsand place them

dressedor nude at variouspoints in the performingareaand to perform

the piece ten times in one eveningwith two- or three-minuteintermis-

sions between performances. Duringthe intermissions,the mannequins

would be moved to differentpositions, or have their costumes changed.

I neverperformedit more than once in an evening,and I neverrented

the mannequins,but the name stuck.53

Diane di Prima,who was fascinatedby Gordon'ssingingduring

MannequinDance,noted the touchingqualitiesof his performance:

"DavidGordonstandsstill a lot. The flow of energy,like a good

crystal set. The receivingand giving out one operation,no

dichotomy there. One incredibledance, Mannequin, where he

moved slowly from one off balanceplie to one other, singingall

the while, [was] somehow terribly moving." Jill Johnston

describedsome of the movementsin Gordon'stwo dancesmore

specifically: "The body bent off center, the head awkwardly

strainedback, the elbows squeezedinto the ribs as the flattened

handsand forearmsmadethe painfulbeauty of spastichelplessness.

As thoughthe body were straining,yelling,againstan involuntary

violence." 54

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 195

Rainerand Gordonwerenot the firstmodem choreographers

to use awkwardmovements. The modem dancersof the 1930s

were criticizedfor using distortionand dissonancein their chore-

ography, and they respondedby arguingthat these were the

qualitiesnecessaryto representmodem times.55 The awkward-

ness of Rainerand Gordon,however,wasnot symbolicallyexpres-

sive. It did not mean pain, as the Grahamcontractionsdid in

Lamentation,for example. In the matter-of-factattitude toward

life and art of the dance of the early 1960s (with movementone

componentof both), awkwardnesswas one partof a gamutof move-

ment and body possibilities-and,perhapsbecauseless familiarin

art but more familiarin life, a moreintriguingone to young choreg-

rapherswho had neverseen firsthandthe stridentmodem danceof

the 1930s, but only its mutated,classicizeddescendants(like the

dancesof Cunninghamand Taylor)and its more dilutedor softened

forms (late Grahamandher followers).

The only extant descriptionof FredHerkoand CecilTaylor's

Like Most People is di Prima'sreview in The Floating Bear, in which

she was frankabouther friend'sshortcomings.

Fred Herko'swork still less clearly defined than those two [Gordonand

Rainer]. Seemsto come from more variedplaces. His danceshappen

inside his costumesa lot ... Like Most People he performedinside

one of those Mexicanhammocks (brightly colored stripes) and Cecil

Taylorplayed the piano. It was some of Cecil'svery exciting playing,

and after a while the dance startedto work with it, and the whole thing

turnedinto somethingmarvelousand unexpected.56

Paxton remembersthat Taylor fell asleepbackstage,and Herko

woke him up just beforethe dancebegan. Taylor"stumbledright

out and startedto play." Thejazz pianistTaylorand Herkoprob-

ably met throughLeRoi Jones and di Prima,co-editorsof The

FloatingBear, a literarynewsletterthat primarilypublishednew

poetry, but also carriedreviews of music (especiallyjazz), art,

theatre,and dance. Herko,a friendandneighborof di Prima'ssince

the mid-l 950s, occasionallywrote for TheFloatingBearandhelped

with its production,as did JamesWaringand Cecil Taylor;Soren

Agenoux (whose pseudonymwas taken from Kierkegaardand the

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

196 DANCECHRONICLE

Frenchphrasemeaning"on one's knees")was anothermemberof

The Floating Bear circle.57

Steve Paxton had madeProxy, item numbereleven, while

on tour with the Cunninghamcompanyin 1961. A trio, danced

by Paxton,YvonneRainer,and JenniferTipton,Proxy wasa "slow-

paceddancein four sections,with two photo movementscoresfor

[sections] two and three:instructionsfor [sections] one and four."

The danceinvolveda greatdeal of walking,standingin a basinfull

of ball bearings,gettinginto poses taken fromphotographs,drink-

ing a glassof water,and eatinga pear. Paxtonspeaksof the dance

as a responseto the workin Dunn'sclasswith John Cage'sscores.

He wantedto go beyond arrangingmovementby chanceProcedures

and actuallymade the movementusing aleatorytechniques. "If

you had the chance process,"Paxton wondered,"why couldn't

it be chance all the way?" Paxton wanted to removethe chore-

ographicprocessalso from the cult of personalimitationthat sur-

roundedmodem dance,a cult that beganwith a directtransmission

of movementsfrom teacherto pupil andended with a hierarchically

structureddance company.58 In Proxy, that learningprocesswas

mediatedby the use of a photo score, which had been made by

gluingcut-outphotographsof people walkingand engagedin sports,

and cartoonimages(Muttand Jeff, plus one froma traveladvertise-

ment) on a largepiece of brownpaper. A movablered dot marked

the beginning,which could be chosen at randomby each dancer.

The score was largeenough that the dancerscould look at it on

the wall while they were dancing. After choosingtheir beginning

point on the score,the dancerscould also choose whetherto take a

linearor a circularpath throughthe images. The rulesset down by

Paxtondictatedthat they must go all the way throughthe scoreand

performas manyrepeatsas wereindicatedon it. But timingand

transitionsbetween the postureswere left up to the dancers. In

rehearsingthe dance,Paxtonprimarilyworkedon gettingthe details

of the posturestranslatedaccurately.59

The first section consistedof eatingand drinking.A small

square had been markedoff with yellow tape on the floor;one per-

formercameinto the square,sat down, and ate a pear. The next

personcameout, stood in the square,and dranka glassof water.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IL~~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Steve Paxton'sProxy in a 1966 performancewith LucindaChilds,Robert

Brown. ?) 1966 by PeterMoore.

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

198 DANCE CHRONICLE

The dancers then walked around the backdrop seven times in large

circles. On one of the circuits, the basin with ball bearings was

deposited on the floor, and one of the dancers stood in it while

another led her around in a circle. In the next two sections, the

picture scores were performed, and in the final section, the per-

formers walked again and picked up the basin.60

The walking, which by the late 1960s would become a hall-

mark of Paxton's choreography, was intended to create a placid,

authoritative, reduced pace. "I tried not to tamper with it too much,

so that it wasn't too special and it just occurred.... Just someone

walking," Paxton explains. The title was a deliberate play on words,

also a hallmark of Paxton's later dances. "The word as a proxy for

the dance, the title being the encapsulation of the thing, and the fact

that the dancers made decisions about what the movement was.

Also, a proxy marriageis one in which a picture is used instead of

the person's actually being there."61 The implication is that the

participant can also be the detached observer who-through a Zen-

like emotional neutrality, repetition of simple actions, and concen-

tration on ordinary things-can examine and confront personal

attachment.

One of the assignments Robert Dunn had given his class

was to take something, cut it up, and reassemble it. Both Carol

Scothorn and Ruth Emerson had done their dances for this assign-

ment to Cage's CartridgeMusic. These cut-ups, Isolations and

Shoulder r, together with CartridgeMusic, are listed on the program

as item number twelve. Scothorn, who taught dance at the Univ-

ersity of Californiaat Los Angeles, was in New York for a year to

study Labanotation; for Isolations she chose to cut up Labanotation

scores. While making the dance, according to Emerson, Scothorn

"had a horrible time. The first thing she had to do was shorten her

neck. She almost gave up the whole project, but she's a very stub-

born person and she worked it out."62

Scothorn remembersIsolations as an attempt to "'push back

the barriers,' that is, to expand the body possibilities beyond the

reflex vocabulary." She recalls the assignment not as a cut-up but

as based on John Cage's Fontana Mix score. One or two trans-

parencies were placed on a page of Labanotation score (rather than

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 199

music paper). The transparencyhad crisscrossinglines on it, and

Scothor assignedeachline a movementvaluebasedon Labanota-

tion concepts. The ends of the lines representedextremesof the

movementvaluesand the middles,neutralor mediumaspectsof the

values. For instance,one line rangedfrom the symbolfor extension

to the symbolfor contraction,anotherfromhigh spatiallevel to low

spatiallevel, a third from clockwiserotation to counterclockwise

rotation. As the lines crossedthe Labanotationstaff, whichmoves

up the pageverticallyandrepresentsbody partswith its columns,

the movementvalue of the line had to be expressedby the body

part intersectingwith that line. Thus the first movementof the

dancerequiredthat the headmove to "placemiddle." Accordingto

Scothorn:

This means the head must telescope into the neck like a turtle's, a very

challenging task! Actually, it was very satisfying in a mind over matter

sort of way. It required total physical concentration to perform the

movement sequences in which different parts performed the same

movement in rapid succession in a non-logical order.

For instance,the line for clockwiserotation passedthrougheach

column,so that the resultingphrasewas a seriesof rotationsthat

passedfromhead to righthand,rightarm,chest, rightleg gesture,

rightsupport,left support,left leg gesture,torso, left arm,left hand.

There were no horizontal lines on the Fontana Mix score, so no move-

ment "chords" were produced. Everything passed rapidly from one

part of the body to the other. There were long periods of silence (when

no line was crossing the staff). The score was assigned a time value

of 1 second to the square.

I remember Merce's reaction, which was one of interest except that

it didn't travel in space. For that to happen, one of the lines would

have had to provide for some other kind of spatial values.63

AlthoughEmersondoesn'trememberwhat kind of material

she herselfcut up, her scoreindicatesthat she also used elements

from Labanotation.Herscorefor Shoulderr lists severalcategories

of elements: space-coveringmovements(walk, run, triplet, crawl,

skip, hop); space(five differentareasof the performancespaceplus

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

200 DANCECHRONICLE

off-stage); geometric patterns (yin-yang circle, circle, vertical

rectangle,horizontalrectangle,triangle,wavyline). Therearealso

elementsof timingand of absolutetime. A secondset of categories

dealt with body parts(rightleg, arm,hand,ribs,head, foot, andleft

leg, arm, hand, shoulder,hips, and spine) and movementqualities

(percussive,swinging,violent, sustained,rotary,heavy). Further

instructionsincludedlow and high levels, stillness,in the air, sit

down;contact floor, focus right,forward,left, down, up, back,still-

ness, front facing,and smile. Five sets of elementswerereshuffled

and set in one order;the secondgroupwas also recombinedand laid

next to the first seriesalong the same time-grid,sometimesover-

lapping. For example,duringthe first five secondsof Shoulderr,

the elementswere "triplet4 very slow wavyline low" and "ribsspine

slow rotaryfloor." For the next fifteen seconds,the firstpartof

the chart reads "hop 4-triangle high," while for the first five of

those secondsit also reads"ribships-rotary floor"and for the next

ten secondsreads"headspinevery fast rotarysmile."64

Although Emersondoes not rememberwhat the dance

looked like, in trying to reconstructit from the score I felt that

Emerson'sresponseto the cut-up assignmentmust have been as

demandingto performas Scothorn'shad been. She had to keep

trackof both locomotion and the changingmovementof separate

body parts. Despitethe fact that the scoresometimescalls for very

slow movement,the dance(as I interpretit) has a qualityof wild

abandon,as if the body weregoingoff in countlessdirectionsall at

once. Thereis an energeticawkwardness,derivingfrom the justa-

position of actions and quickly shiftinglevels that was presentin

the earlyworkof PaulTaylorand MerceCunningham.Emerson's

title was also a joke, because "shoulderr" was one element that

neverenteredinto the chartat all.

WilliamDavis'sCrayonwas item numberthirteenon the

program. Davis,who had been dancingsince he was a child in

southernCalifornia,had moved to New York in 1959 and joined

MerceCunningham's companyin 1961. AlthoughDavishad never

taken Dunn'schoreographyclass,he wasclose to many of Dunn's

students;he took dance classeswith them both at the Cunning-

ham studio and at the JoffreyBallet School, and he dancedin

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 201

Cunningham'scompanywith Steve Paxton and Judith Dunn. He

dancedwith Rainerin Waring'swork. He also dancedin Rainer's

Dance for 3 People and 6 Arms in the Judson program. So he was

invitedto contributea dance.

Crayonwas a solo accompaniedby threerock-and-rollsongs:

"I Love You," by the Volumes;"Iey Little Girl,"by Dee Clark;

and "Baby,Oh Baby,"by the Shells. In the traditionof Merce

Cunninghamand John Cage,the dancingwasnot done to the music,

but co-existedwith it in time and space,an effect that wasjarring

when the music had the four-square,propulsivebeat of rock-and-

roll. The dancebeganin silence,and afterabout twenty secondsthe

threesongsfollowedin sequence. Davisrecalls:

I was hoping to set up an exhilaratingsurprise,and I felt if I didn't

establisha kinetic line first, it might not be possibleto keep any separa-

tion. The movementwas to ride along on top of the sound like riding

a wave, and I wanteda paddlinghead start, to get aheadof the crest

and avoid being swampedin the rhythmor the sentimentof the music.

The first recordwas the Volumes' "I Love You," which takes off

with insistent rhythmand a loud rush of harmonicsweetnessof sound

and lyrics. This was pre-Beatles,and pop music was still just for its

own audience. I went straightfor sentimentalforce.

Therewereno populardancestepsin Crayonto correspondwith the

popularmusic,nor weretherecharacterizations or movementjokes.

"It wasn't overtly funny, though I rememberthat people reacted

with laughter,"Davissays. "I supposethe movementmust have

seemedCunninghamesque, with overtonesof ballet."

Of the actual movements,amongthe few things I can rememberare a

large, vertical-circlingone-arm port de bras, rather like the "lyre

strumming"in Balanchine'sApollo; a horizontalcirclingof one hand

aroundthe head (as though wipinga gianthalo) while the other hand

shimmeredpalm down out to the side at the end of a straight,extended

arm;and some skittering,rabbit-hopping,two-step jumps in releve

plie on a downstagediagonal. There were severaluses of a pointing

fingerin the dance, to indicate a directionof energy,or just as little

emblems-like Paul Klee arrows.65

WalterSorrell,reviewingCrayonat a laterconcert,suggests

that the dance is emblematicof a hip, angryyoung generationof

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

William Davis in Crayon as performed in February 1963 at Judson Hall. P

This content downloaded from 194.80.193.190 on Thu, 26 Jun 2014 08:27:19 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JUDSONDANCETHEATRE 203

rebels.65 Perhaps,despite Davis'srepudiationof characterization

in the solo, the dancedid exude the senseof joyous defiancethat

popularsongsin the early 1960s extolled. Paxtonremembersbeing

thrilledby Crayon'sfreshness

It seemedlike a logical thing to do in a way; it was a collagistmentality.

But no one was collaging what was really current. Everybody [in

dance] seemed to be into esotericaor surrealqualitiesin their work.

Bill seemed to be pretty up-frontabout includingthe whole realmof

pop music in the dance scene, suggestinga kind of earthinessand

raunchinessthat was totally lacking otherwise. Everybodyelse was

either in an intellectual sphere or involved in artistic choice-making

that included fairly decadent, decorativeart. Crayonwas very re-

freshingin this slightly rarefiedatmosphere.67

FollowingCrayon,Rainerperformeditem numberfourteen,

her solo OrdinaryDance. Choreographed duringthe time of Dunn's

class,OrdinaryDance was not a solutionto an assignment;nor did

it springfrom a scoreor from chanceprocedures."By then I was