Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aging and Down Syndrome - Implications For Physical Therapy

Uploaded by

Mónica ReisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aging and Down Syndrome - Implications For Physical Therapy

Uploaded by

Mónica ReisCopyright:

Available Formats

Update

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

Aging and Down Syndrome:

Implications for Physical Therapy

Robert C Barnhart, Barbara Connolly

RC Barnhart, PT, ScDPT, PCS, is

Assistant Professor and Academic

The number of people over the age of 60 years with lifelong developmental delays is

Coordinator of Clinical Education,

predicted to double by 2030. Down syndrome (DS) is the most frequent chromo- Department of Physical Therapy,

somal cause of developmental delays. As the life expectancy of people with DS East Tennessee State University,

increases, changes in body function and structure secondary to aging have the Box 70624, Johnson City, TN

potential to lead to activity limitations and participation restrictions for this popula- 37614. Address all correspon-

dence to Dr Barnhart at:

tion. The purpose of this update is to: (1) provide an overview of the common body

barnhart@etsu.edu.

function and structure changes that occur in adults with DS as they age (thyroid

dysfunction, cardiovascular disorders, obesity, musculoskeletal disorders, Alzheimer B Connolly, PT, EdD, FAPTA, is

UTNAA Distinguished Service Pro-

disease, depression) and (2) apply current research on exercise to the prevention of

fessor and Chairperson, Graduate

activity limitations and participation restrictions. As individuals with DS age, a shift in Program in Physical Therapy, Uni-

emphasis from disability prevention to the prevention of conditions that lead to versity of Tennessee Health Sci-

activity and participation limitations must occur. Exercise programs appear to have ence Center, Memphis, Tenn.

potential to positively affect the overall health of adults with DS, thereby increasing [Barnhart RC, Connolly B. Aging

the quality of life and years of healthy life for these individuals. and Down syndrome: implications

for physical therapy. Phys Ther.

2007;87:1399 –1406.]

© 2007 American Physical Therapy

Association

Post a Rapid Response or

find The Bottom Line:

www.ptjournal.org

October 2007 Volume 87 Number 10 Physical Therapy f 1399

Aging and Down Syndrome

A

pproximately 200,000 to strictions. The conceptual model Changes in Body Structure

500,000 individuals over the guiding the discussion in this update and Function Associated

age of 60 have lifelong devel- will be the World Health Organiza- With Aging in Individuals

opmental delays (DD), representing tion’s International Classification

approximately 12% of people of all of Function, Disability and Health

With DS

One of the goals of Healthy People

ages with DD.1,2 This number is pre- (ICF).12

2010 is to increase quality of life and

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

dicted to double by 2030.3 The ma-

the years of healthy life of all citizens

jority of these individuals live with The ICF provides a common lan-

of the United States.14 As individuals

family members.4 This living situa- guage and framework for the de-

with DS age, they are more suscep-

tion is a growing concern for social scription of health and health-related

tible to age-related physical and neu-

service agencies serving this popula- states, outcomes, and determi-

rological or psychiatric conditions

tion because many individuals with nants.12,13 The ICF emphasizes

than the general population.15

DD are now outliving their parents health and functioning, rather than

and family members. disability, and is a tool for measuring

Physical Conditions

functioning in society regardless of

The physical conditions seen in

Down syndrome (DS) is the most fre- the reason for an individual’s impair-

people with DS include thyroid dys-

quent chromosomal cause of DD, oc- ments.12 Thus, the ICF focuses on a

function, cardiovascular disorders,

curring in 1 out of every 700 to 1,000 person’s level of health rather than

obesity, and musculoskeletal disor-

live births.5–7 More than 350,000 on disability. The emphasis on an

ders.5,16 These physical problems

people in the United States have individual’s level of health is impor-

can have a negative effect on the

been diagnosed with DS.8 The non- tant because diagnosis alone does

quality of life not only for people

disjunctive type of trisomy 21 is not predict service needs, level of

with DS but their families as

present in 93% to 95% of individuals care, or functional outcomes.12

well.9,17,18

with DS.5,9 Less common causes of

DS are translocation, when part of The ICF model identifies 3 levels of

Thyroid dysfunction. Adults with

chromosome 21 breaks off and at- human functioning.12 Human func-

DS are at risk for developing both

taches to another chromosome, and tioning occurs at the level of body or

hyperthyroid and hypothyroid con-

mosaicism, where the nondisjunc- body part (body function and struc-

ditions as they age, with hypothy-

tion of chromosome 21 occurs be- ture), the execution of a task by a

roidism being more common.5–7,19

fore cell fertilization.5 Translocations person (activities), and the whole

Studies have shown that 20%

are responsible for approximately person in a social context (participa-

(age⫽6 –14 years)17 to 28.1% (age⫽5

3% to 4% of cases of DS, whereas tion). Figure 1 illustrates the ICF

days–10 years)18 of children with DS

mosaicism occurs in about 1% to 3% model.

have thyroid dysfunction on initial

of cases.9

thyroid function testing, with the

In the ICF model, disability and func-

majority of these children demon-

Like that for other individuals with tioning are seen as the outcome of

strating hypothyroidism.20 By adult-

DD, the life expectancy for individ- the interaction between health con-

hood, approximately 40% of all

uals with DS has been increasing ditions (diseases, disorders, and inju-

people with DS will develop hypo-

from an average of 9 years of age in ries) and contextual factors.12 Con-

thyroidism.5,6 Untreated hypothy-

1929,9 to 12 years of age in 1949,9 to textual factors include both

roidism often can lead to symptoms

35 years of age in 1982,9 to 55 years environmental and personal factors.

that mimic a decline in cognitive

of age or older currently.5,6,10,11 Environmental factors are external

skills; therefore, individuals may be

Therefore, changes in body function and include social attitudes, culture,

misdiagnosed as having Alzheimer

and structure secondary to aging geography, and architectural distinc-

disease (AD).5,6 Other frequently ob-

have the potential to lead to activity tiveness. Personal factors are internal

served symptoms of hypothyroidism

limitations and participation restric- and include sex, age, personality

in individuals with DS include de-

tions for individuals with DS. The characteristics, social background,

creased energy, decreased motiva-

purpose of this update is to: (1) pro- education, life experiences, voca-

tion, weight gain, constipation, bra-

vide an overview of the common tional and avocational activities, and

dycardia, and dry skin.5

body function and structure changes any other factors that might influ-

that occur in adults with DS as they ence how a person experiences

Cardiovascular disorders. Mitral

age and (2) apply current research disability.

value prolapse is reported to occur

on exercise to the prevention of ac-

in 46% to 57% of adults with DS.6,7

tivity limitations and participation re-

1400 f Physical Therapy Volume 87 Number 10 October 2007

Aging and Down Syndrome

Mitral value prolapse can lead to an

increased risk of endocarditis, cere-

brovascular accident, more severe

mitral value prolapse, and heart fail-

ure.5 Mitral value prolapse can occur

in adults with DS who have no pre-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

vious history of cardiac pathology.

Therefore, some experts7,21 contend

that a second cardiac assessment

should be given to all adolescents

and young adults with DS, regardless

of whether cardiac symptoms are

present, especially before dental or

surgical procedures. Early signs of

mitral value prolapse include fatigue,

irritability, weight gain, dyspnea Figure 1.

with physical activity, bilateral crack- The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Reprinted

les that do not clear with a cough, from Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability, and Health: ICF. Geneva,

and a third heart sound.5 As with Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002, with permission of the World Health

Organization, all rights reserved by the World Health Organization.

hypothyroidism, some symptoms of

mitral value prolapse could be con-

fused with symptoms frequently tions) to maximal exercise in young among body mass index (BMI), diet,

seen in people with AD. adults (15–20 years of age) with DS. and exercise in adults with DS. They

The lower cardiovascular capacities discovered a significant link (P⫽

Adults with DS may also have a lower reported in adults with DS may lead .033) between friendships or access

cardiovascular capacity than their to participation restrictions specifi- to recreation and BMI.19 They con-

peers who are mentally challenged cally related to job performance. Job cluded that community interactions

but do not have DS. Pitetti et al22 performance frequently is related to have a major effect on health. Their

studied the cardiovascular response physical fitness levels, and a lower findings are consistent with the the-

to exercise testing in adults with DS cardiovascular capacity may place oretical model underlying the ICF

and adults with mental retardation these adults at a disadvantage in that environmental factors can influ-

without DS. They discovered that in- performing job-related physical ence participation levels.

dividuals with DS had significantly activities.22

lower (P⬍.01) mean peak oxygen Andriolo et al31 and Luke et al32 the-

consumption, minute ventilation, Obesity. Men with more than 25% orized that a lower resting metabolic

and heart rate during exercise test- body fat and women with more than rate was a cause of increased rates of

ing. Similar results regarding maxi- 35% body fat are considered obese.26 obesity in individuals with DS. Be-

mum oxygen consumption in adults Adults with DS also have reported cause both of those studies involved

with DS also were reported by Pitetti high rates of obesity.23,26,27 Some au- children with DS, Fernhall et al33

and Boneh.23 thors28,29 have suggested that adults tested this hypothesis by measuring

with DS tend to lead a sedentary life- the resting metabolic rate in 22

The lower cardiovascular capacity in style, which results in increased adults with DS (17–39 years of age)

adults with DS may be secondary to rates of obesity. In a study of physical and compared these results with

a lower lean body muscle mass, inactivity among adults with mental those of 20 age-matched control sub-

lower muscle strength (force- retardation, Draheim et al30 reported jects who were not disabled. When

generating capacity), thyroid disor- that less than 46% of the men and the presence of thyroid disease was

ders, hypotonic muscle tone women participated in the recom- controlled, the resting metabolic rate

(velocity-dependent resistance to mended amount of physical activity in adults with DS was similar to that

stretch), higher incidences of obe- and no adults over 30 years of age in the general population. They con-

sity, or an impaired sympathetic re- reported participation in vigorous cluded that a lower resting meta-

sponse to exercise.22,24 For example, physical activity. bolic rate found in children with DS

Eberhard et al25 found impaired sym- may predispose them to obesity as

pathetic responses (lower peak heart However, Fujiura et al19 reported adults.

rate and blood lactate concentra- that there were not strong links

October 2007 Volume 87 Number 10 Physical Therapy f 1401

Aging and Down Syndrome

Musculoskeletal disorders. Be- thyroid disease observed in adults Neurological or

cause of premature aging, adults with DS compared with adults in the Psychiatric Conditions

with DS might experience musculo- general population and adults with The most commonly described neu-

skeletal disorders usually associated other forms of mental retardation rological or psychiatric condition as-

with elderly individuals earlier than also may contribute to the increased sociated with aging in individuals

the general population.5 Juvenile ar- prevalence of osteoporosis in people with DS is AD. Depression also may

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

thritis–like arthropathy develops in with DS.5,17,38 be seen. Early identification and

approximately 1% to 2% of adoles- treatment of AD and depression

cents with DS.7 Mid-cervical arthritis Other frequent conditions. Sev- could reverse the functional decline

also has been reported to occur at a eral other conditions have been as- frequently associated with these

higher rate in adults with DS than in sociated with the aging process in disorders.45

the general population.5,6 Possibly as DS. Children and young adults with

a result of low muscle tone, adults DS have a high prevalence of middle Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer

with DS are at increased risk for hip ear infections and conductive hear- disease continues to be an ongoing

dysplasia with dislocation and foot ing loss.39,40 The prevalence of hear- area of research in adults with DS.46

pronation.5 Hresko et al34 found pro- ing impairment increases with age.40 Almost all adults with DS over 40

gressive hip instability after skeletal Conductive hearing loss has been re- years of age display neuropathology

maturity in individuals with DS, ported to be occurring at rates as consistent with AD.47 Prevalence

which led to a decrease in ambula- high as 70% in adults with DS com- rates for AD among adults with DS

tion skills. Foot pronation may lead pared with 8% in adults who are increase with age, with rates of 10%

to an increased incidence of pedal mentally challenged but do not have at 30 to 39 years of age, up to 55% at

arthritis in adults with DS.7 DS.5,41 Therefore, examinations of 50 to 59 years of age, and almost 75%

hearing should occur every 2 years at 60 to 65 years of age.6,47 In addi-

Individuals with DS also appear to be once adulthood is reached.5 tion, women with DS who experi-

at higher risk for developing osteo- ence menopause before 46 years of

porosis than the general population. Adults with DS also may be at risk for age have an increased risk for and an

In a study of individuals with mental the development of vision problems. earlier onset of AD.37

retardation who were living in the The prevalence of visual impairment

community, Center et al35 found a in adults with DS who are 65 to 74 The increased prevalence of AD is

significantly lower bone mineral den- years of age is 70% compared with theorized to be caused by an over-

sity (BMD) (P⫽.0008 for women and 6.5% of adults of the same age who expression of the gene for amyloid

P⫽.0006 for men) in these individu- are not mentally challenged and precursor protein due to a triplica-

als compared with the general pop- compared with 17.4% of adults of tion of chromosome 21 found in

ulation. Down syndrome was discov- the same age who are mentally chal- most cases of DS.24 This over-

ered to be an independent risk factor lenged who do not have DS.42 Vision expression leads to an increased ac-

for osteoporosis. The relatively problems include cataracts, blepha- cumulation of -amyloid, the princi-

young age (mean⫽35 years) of the ritis, keratoconus, and excessive pal component of senile plaques in

individuals in the study is of particu- myopia, all of which appear to in- the brain.24 Symptoms of AD fre-

lar concern. crease in frequency with increasing quently observed in adults with DS

age.5–7,41,43 The loss of either hearing include memory loss, weight loss,

Other researchers36 also have found or vision can have a detrimental ef- decreased skills in activities of daily

that individuals with DS appear to be fect on adaptive behavior in adults living leading to increased depen-

at risk for developing osteoporosis as with DS.44 dency, personality changes, apathy,

they age. Subsequently, long-bone late-onset epilepsy, and loss of con-

fractures and compression factures Skin disorders such as atopic derma- versation skills (Fig. 2).7,16,46,48 –51 In

of the vertebral bodies are common titis, fungal infections of skin and addition, increased rates of depres-

in this population.18 The increased nails, and xerosis are common in sion and mobility problems appear

incidence of osteoporosis among adults with DS.7 Finally, sleep apnea to develop as AD progresses.49,51

adults with DS may be secondary to is reported to occur in approxi- Eighty-four percent of adults with DS

several factors, including their short mately 50% of adults with DS.5 Sleep who have end-stage AD also develop

stature, low muscle tone, decreased apnea in adults with DS may lead to late-onset epilepsy.51

physical activity, early menopause, depression, paranoia, irritability, or

and decreased muscle strength.37 In other behavioral changes.6 Depression. Mental illness occurs

addition, the increased incidence of in approximately 30% of all adults

1402 f Physical Therapy Volume 87 Number 10 October 2007

Aging and Down Syndrome

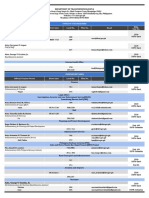

with DS.5 Depression is the most fre- Weight loss48

quent mental health issue in adults Memory loss46

with DS and is a common cause of Increased dependency in activities of daily living46

decreased function among these Personality changes, including depression 7,16,46

adults. Other common symptoms of Decrease in conversation skills7,16

depression in DS include sleep and Loss of mobility skills49,51

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

behavior disturbances, apathy, and Development of seizures 50

weight change.5 One difficulty in di- Figure 2.

agnosing depression in this popula- Frequently observed symptoms of Alzheimer disease in adults with Down syndrome.

tion is differentiating between de-

pression and the symptoms of AD or

thyroid disease.7,48 In conclusion, exercise to improve with an increase in the level of dis-

BMD in adults with DS may have ability.56 Therefore, involvement in

Exercise and limited benefits because of their cardiovascular conditioning pro-

Down Syndrome long-standing low BMD as well as grams would appear to be important

This section reviews the literature additional comorbidities.55 Exercise for individuals with mental retarda-

examining the effect of exercise on during skeletal growth has been tion. However, can the cardiovascu-

osteoporosis, cardiovascular func- demonstrated to influence BMD dur- lar fitness levels of individuals with

tion, and muscle strength in adults ing the adult years.54 Physical thera- mental retardation, specifically those

with DS. Only studies specifically tar- pists, therefore, should emphasize with DS, be improved with exercise?

geting adults (subjects over 18 years dynamic (active) weight bearing

of age) with DS are summarized. when working with children with Varela et al59 investigated the effects

DS who are either ambulatory or of an aerobic rowing program on the

Osteoporosis nonambulatory. Partial body-weight– cardiovascular fitness of young

As stated previously, individuals with supported treadmill training may adults with DS. Sixteen men (mean

DS have been shown to have de- provide a means for dynamic weight age⫽21.4 years) with DS were as-

creased BMD compared with other bearing to improve BMD for both signed to either an exercise group or

people with mental retardation and children who are nonambulatory a no-exercise (control) group. All

individuals without DD.52 Physical and adults with DS. Additional re- participants were tested on treadmill

activity has been shown to be related search is needed to determine which and rowing machines before and af-

to increased BMD in individuals therapies are best for improving and ter the exercise program. The exer-

without DD.53 Could increased phys- maintaining BMD in adults with DS. cise group was involved in a rowing

ical activity also increase BMD program using rowing machines for

among individuals with DS? Angelo- Cardiovascular Fitness 25 minutes per session, 3 sessions

poulou et al52 found a significant re- Compared with their peers who are per week, for 16 weeks. The authors

lationship (r⫽.877, P⬍.01) between not mentally retarded, individuals found no significant difference be-

quadriceps femoris muscle strength with DS, regardless of their age, have tween the exercise and control

and BMD among men with DS. They lower cardiovascular fitness lev- groups in peak oxygen uptake, max-

concluded that encouraging an ac- els.28,56,57 This lower level of cardio- imal heart rate, and minute ventila-

tive lifestyle and exercise for indi- vascular fitness may be the result of tion following the 16-week rowing

viduals with DS would help pre- poor eating habits, sedentary life- program. However, they found that

vent osteoporosis. In their review style, lack of opportunity for recre- the exercise group was able to row

of literature on the effect of exercise ational activities, poor coordination, and walk for longer distances

on BMD, however, Turner and and poor motivation for physical ac- (P⬍.05) following involvement in

Robling54 concluded that exercise tivity.28,56 In addition, the lack of car- the rowing program, demonstrating

has only a minor effect on increasing diovascular fitness may be secondary improvements in exercise capacity

BMD after skeletal maturity but that to or caused by the elevated obesity without improvements in cardio-

exercise can reduce fracture risk by rates observed among adults with vascular fitness.

decreasing the number of falls an el- mental retardation.30 Poor cardio-

derly person may experience by vascular fitness levels also may con- Tsimaras et al28 investigated the car-

improving balance and postural tribute to the increased risk for heart diovascular response in young adults

stability. disease and stroke in adults with (mean age⫽24.5 years) with DS fol-

mental retardation.58 In addition, lowing a 12-week jog-walk aerobic

cardiovascular fitness levels decrease program. Unlike Varela et al,59 how-

October 2007 Volume 87 Number 10 Physical Therapy f 1403

Aging and Down Syndrome

ever, Tsimaras et al monitored the uals with DS who are over 30 years and without resistance and ended

participants’ exercise heart rate of age. with a 5-minute recovery period.

closely and gave reinforcements (ed- The experimental group demon-

ible, verbal, and visual) to the partic- Strength Training strated significant (P⬍.01) improve-

ipants during the exercise program. Rimmer et al29 investigated the ef- ments in isokinetic peak torque and

The authors believed that these fects of a strength training program isokinetic endurance of the lower

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

changes in the exercise protocol ex- on adults (mean age⫽38.6 years) extremities following the training

plained why their results were differ- with DS. In this study, 30 adults with program. The control group showed

ent from the results reported by DS participated in 15 to 20 minutes no improvement in peak torque or

Varela et al. of strength training, 3 days per week, endurance. The experimental group

for 12 weeks. Muscle strength was also showed a significant improve-

Unlike the study by Varela et al,59 measured before and after training ment (30 seconds: P⬍.01; 45 sec-

participants in the exercise program and compared with that in 22 indi- onds: P⬍.001; 60 seconds: P⬍.01) in

in the study by Tsimaras et al28 dem- viduals with DS who did not par- dynamic balance.61

onstrated significant improvement ticipate in any strength training dur-

(P⬍.05) in all physiological parame- ing the same time period. The The results from both of these stud-

ters compared with the control authors found that the individuals ies29,61 are important because many

group, which did not exercise. As in who participated in the strength individuals with DS will need to

the study by Varela et al, lower base- training program demonstrated sig- maintain or improve their muscular

line maximal heart rate and baseline nificant (P⬍.0001) gains in muscular strength in order to keep working as

peak oxygen uptake were found in strength compared with the individ- they grow older. Furthermore, be-

individuals with DS compared with uals in the control group. The indi- cause individuals with DS are at risk

individuals without DS. Baynard et viduals in the exercise group also for obesity, strength training may

al27 hypothesized that the lower demonstrated a significant (P⬍.01) provide a means for weight control.

maximal heart rate may be due to a decrease in body weight following

reduced sympathetic drive and circu- the exercise program. Summary

lating catecholamines. The lower Exercise programs appear to have

peak oxygen uptake may be due to Tsimaras and Fotiadou61 studied the the potential to positively affect the

increased body fat in individuals effects of training on quadriceps overall health of adults with DS,

with DS.28 femoris and hamstring muscle thereby increasing the quality of life

strength and dynamic balance (bal- and years of healthy life for these

In summary, young adults with DS ance associated with walking62) in individuals. However, there is a need

between the ages of 21 and 24 years 25 men (mean age⫽24.5 years) with for more research investigating the

may show improvements in cardio- DS. Fifteen men were assigned to an effects of exercise on adults with DS

vascular fitness following a well- exercise group, and 10 men were over 40 years of age. In their meta-

designed and closely supervised assigned to a control group. All sub- analysis of aerobic exercise pro-

aerobic exercise program. The im- jects took part in testing of peak grams for adults with DS, Andriolo et

provements shown in peak oxygen torque, isokinetic muscle endur- al31 identified only 2 studies of good

uptake following aerobic exercise ance, and dynamic balance before quality.

are particularly important because and after the exercise program. Dy-

individuals with DS have a lower namic balance was measured No studies were found investigating

baseline peak oxygen uptake com- through the use of a balance deck the effects that exercise may have on

pared with individuals without DS. and determined by a stabilometer in the symptoms of AD in the popula-

Without intervention, the peak oxy- 30-, 45-, and 60-second intervals. tion with DS. Because exercise has

gen uptake can be expected to de- been shown to modify brain func-

crease as people with DS age, which The experimental group was in- tion63 and may be related to im-

could result in their inability to per- volved in a 12-week exercise pro- proved cognitive functioning among

form activities of daily living and per- gram at a frequency of 3 sessions per adults without DS,64,65 exercise may

form light work duties, leading to week for 30 to 35 minutes per ses- help decrease the severity of symp-

activity and participation restric- sion. Each session consisted of a 10- toms experienced by adults with DS

tions.28,60 Unfortunately, no studies minute warm-up period followed by who also have AD. Additional re-

have investigated the effects of an a 15- to 20-minute training period search investigating the effects of ex-

aerobic exercise program on individ- consisting of dynamic balance activ- ercise on the symptoms of AD

ities and plyometric exercises with

1404 f Physical Therapy Volume 87 Number 10 October 2007

Aging and Down Syndrome

among individuals with DS is 6 Smith DS. Health care management of 23 Pitetti KH, Boneh S. Cardiovascular fitness

adults with Down syndrome. Am Fam as related to leg strength in adults with

needed. Physician. 2001;64:1031–1038. mental retardation. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

1995;27:423– 428.

7 Roizen NJ, Patterson D. Down’s syn-

Conclusion drome. Lancet. 2003;361:1281–1289. 24 Lott IT, Head E. Down syndrome and Alz-

heimer’s disease: a link between develop-

Healthy People 2010 has set a goal of 8 Steiner WA, Ryser L, Huber E, et al. Use of ment and aging. Ment Retard Dev Disabil

the ICF model as a clinical problem-

increasing the quality of life and solving tool in physical therapy and reha- Res Rev. 2001;7:172–178.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

years of healthy life for all the citi- bilitation medicine. Phys Ther. 2002;82: 25 Eberhard Y, Eterradossi J, Therminarias A.

1098 –1107. Biochemical changes and catecholamine

zens of the United States.14 Individu- responses in Down syndrome adolescents

9 Bittles AH, Glasson EJ. Clinical, social, and

als with DS face many challenges as ethical implications of changing life ex- in relation to incremental maximal exer-

cise. J Ment Defic Res. 1991;35:140 –146.

they age, including a number of age- pectancy in Down syndrome. Dev Med

Child Neurol. 2004;46:282–286. 26 Wilmore JH, Costill DL. Physiology of

related conditions that could lead to Sport and Exercise. 2nd ed. Champaign,

10 Glasson EJ, Sullivan SG, Hussain R, et al.

activity and participation limitations. The changing survival profile of people Ill: Human Kinetics; 1999.

Therefore, a shift in emphasis from with Down’s syndrome: implications for 27 Baynard T, Pitetti KH, Guerra M, Fernhall

genetic counseling. Clin Genet. 2002;62: B. Heart rate variability at rest and during

disability prevention to the preven- 390 –393. exercise in persons with Down syndrome.

tion of conditions that could poten- 11 Silverman W, Zigman WB, Huykang K, Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:

1285–1290.

tially lead to activity and participa- et al. Aging and dementia among adults

with mental retardation and Down syn- 28 Tsimaras V, Giagazoglou P, Fotiadou E,

tion limitations must occur.66 drome. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilita- et al. Jog-walk training in cardiorespiratory

Physical therapists who frequently tion. 1998;13:49 – 64. fitness of adults with Down syndrome.

Percept Mot Skills. 2003;96:1239 –1251.

serve children with DS and their fam- 12 Towards a Common Language for Func-

tioning, Disability, and Health: ICF. Ge- 29 Rimmer JH, Heller T, Wang E, Valerio L.

ilies need to keep in mind that the neva, Switzerland: World Health Organiza- Improvements in physical fitness in adults

majority of these children will live tion; 2002. with Down syndrome. Am J Ment Retard.

2004;109:165–174.

well into adulthood. Emphasizing 13 Palisano RJ, Campbell SK, Harris SR.

Evidence-based decision making in pediat- 30 Draheim CC, Williams DP, McCubbin JA.

the importance of consistent exer- ric physical therapy. In: Campbell SK, Prevalence of physical inactivity and rec-

cise, good diet, community involve- Vander Linden DW, Palisano RJ, eds. Phys- ommended physical activity in

ical Therapy for Children. 3rd ed. St community-based adults with mental retar-

ment, and regular health examina- Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders; 2006:3–32. dation. Ment Retard. 2002;40:436 – 444.

tions throughout their life may help 14 Healthy People 2010: Understanding and 31 Andriolo RB, El Dib RP, Ramos LR. Aerobic

these children and their families to Improving Health. Washington, DC: US exercise training programs for improving

Department of Health and Human Servic- physical and psychosocial health in adults

increase the length and quality of es; 2000. with Down syndrome. Cochrane Data-

their life. 15 Day SM, Strauss DJ, Shavelle RM, Reynolds base Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD005176.

RJ. Mortality and causes of death in per- 32 Luke A, Roizen NJ, Sutton M, Schoeller

sons with Down syndrome in California. DA. Energy expenditure in children with

Dr Barnhart provided concept/idea/research Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:171–176. Down syndrome: correcting metabolic

rate for movement. J Pediatr. 1994;125(5

design. Both authors provided writing. 16 Thompson SB. Examining dementia in Pt 1):829 – 838.

Down syndrome (DS): decline in social

This article was submitted November 3, 2006, abilities in DS compared to other learning 33 Fernhall B, Figueroa A, Collier S, et al.

and was accepted May 29, 2007. disabilities. Topics in Clinical Gerontol- Resting metabolic rate is not reduced in

ogy. 1999;20:23– 44. obese adults with Down syndrome. Ment

DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20060334 Retard. 2005;43:391– 400.

17 Kapell D, Nightingale B, Rodriguez A,

et al. Prevalence of chronic medical con- 34 Hresko MT, McCarthy JC, Goldberg MJ.

ditions in adults with mental retardation: Hip disease in adults with Down syn-

comparison with the general population. drome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:

References Ment Retard. 1998;36:269 –279. 604 – 607.

1 Connolly BH. Aging in individuals with 18 van Allen MJ, Fung J, Jurenka SB. Health 35 Center J, Beange H, McElduff A. People

lifelong disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pe- concerns and guidelines for adults with with mental retardation have an increased

diatr. 2001;21:23– 47. Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999; prevalence of osteoporosis: a population

2 Nochajski SM. The impact of age related 89:100 –110. study. Am J Ment Retard. 1998;103:

changes on the functioning of older adults 19 –28.

19 Fujiura GT, Fitzsimons N, Marks B, Chi-

with developmental disabilities. Phys Oc- coine B. Predictors of BMI among adults 36 Tyler CV Jr, Snyder CW, Zyzanski S.

cup Ther Geriatr. 2000;18:5–21. with Down syndrome: the social context Screening for osteoporosis in community-

3 Hammel J, Nochajski SM. Aging and devel- of health promotion. Res Dev Disabil. dwelling adults with mental retardation.

opmental disability: current research, pro- 1997;18:261–274. Ment Retard. 2000;38:316 –321.

gramming, and practice implications. Phys 20 Tuysuz B, Beker DB. Thyroid dysfunction 37 Schupf N, Pang D, Patel BN, et al. Onset of

Occup Ther Geriatr. 2000;18:1– 4. in children with Down’s syndrome. Acta dementia is associated with age at meno-

4 Braddock D, Emerson E, Felce D, Stancliffe Paediatr. 2001;90:1389 –1393. pause in women with Down’s syndrome.

RJ. Living circumstances of children and Ann Neurol. 2003;54:433– 438.

21 Feingold M, Geggel RL. Health supervision

adults with mental retardation or develop- for children with Down syndrome. Pedi- 38 Cooper SA. Clinical study of the effects of

mental disabilities in the United States, atrics. 2001;108:1384. age on the physical health of adults with

Canada, England and Wales, and Australia. mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard.

Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001; 22 Pitetti KH, Climstein M, Campbell KD, 1998;102:582–589.

7:115–121. et al. The cardiovascular capacities of

adults with Down syndrome: a compara- 39 Smith DS. Health care management of

5 Finesilver C. A new age for childhood dis- tive study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24: adults with Down syndrome. Am Fam

eases: Down syndrome. RN. 2002;65: 13–19. Physician. 2001;64:1031–1038.

43– 48.

October 2007 Volume 87 Number 10 Physical Therapy f 1405

Aging and Down Syndrome

40 Evenhuis HM. Medical aspects of ageing in 50 McVicker RW, Shanks OE, McClelland RJ. 58 Sutherland G, Couch M, Iacono T. Health

a population with intellectual disability, II: Prevalence and associated features of epi- issues for adults with developmental dis-

hearing impairment. J Intellect Disabil lepsy in adults with Down’s syndrome. ability. Res Dev Disabil. 2002;23:

Res. 1995;39(Pt 1):27–33. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:528 –532. 422– 445.

41 van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk HM, 51 McCarron M, Gill M, McCallion P, Begley 59 Varela AM, Sardinha L, Pitetti KH. Effects

Haveman MJ, Maaskant MA, et al. The C. Health co-morbidities in ageing persons of an aerobic rowing training regimen in

need for assessment of sensory function- with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s de- young adults with Down syndrome. Am J

ing in ageing people with mental handi- mentia. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005;49(Pt Ment Retard. 2001;106:135–144.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/87/10/1399/2742283/ by B-On Consortium Portugal user on 08 October 2019

cap. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1994;38(Pt 3): 7):560 –566. 60 Fernhall B. Physical fitness and exercise

289 –298. 52 Angelopoulou N, Matziari C, Tsimaras V, training of individuals with mental retar-

42 Kapell D, Nightingale B, Rodriguez A, et al. Bone mineral density and muscle dation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:

et al. Prevalence of chronic medical con- strength in young men with mental retar- 442– 450.

ditions in adults with mental retardation: dation (with and without Down syn- 61 Tsimaras VK, Fotiadou EG. Effect of train-

comparison with the general population. drome). Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66: ing on the muscle strength and dynamic

Ment Retard. 1998;36:269 –279. 176 –180. balance ability of adults with Down syn-

43 Evenhuis HM. Medical aspects of ageing in 53 Prior JC, Barr SI, Chow R, Faulkner RA. drome. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18:

a population with intellectual disability, I: Prevention and management of osteoporo- 343–347.

visual impairment. J Intellect Disabil Res. sis: consensus statements from the Scien- 62 Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Motor

1995;39(Pt 1):19 –25. tific Advisory Board of the Osteoporosis Control: Translating Research Into Clini-

Society of Canada, 5. Physical activity as

44 Prasher VP, Chung MC. Causes of age- cal Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lip-

therapy for osteoporosis. CMAJ. 1996;155:

related decline in adaptive behavior of pincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

940 –944.

adults with Down syndrome: differential 63 Sutoo D, Akiyama K. Regulation of brain

diagnoses of dementia. Am J Ment Retard. 54 Turner CH, Robling AG. Designing exer- function by exercise. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;

1996;101:175–183. cise regimens to increase bone strength. 13:1–14.

Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003;31:45–50.

45 Evenhuis HM, Henderson CM, Beange H, 64 Ball LJ, Birge SJ. Prevention of brain aging

et al. Healthy Ageing—Adults With Intel- 55 Baer MT, Kozlowski BW, Blyler EM, et al. and dementia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:

lectual Disabilities: Physical Health Is- Vitamin D, calcium, and bone status in 485–503.

sues. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health children with developmental delay in re-

Organization; 2000. lation to anticonvulsant use and ambula- 65 Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ. The

tory status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65: effects of exercise training on elderly per-

46 Prasher V, Cunningham C. Down syn- 1042–1051. sons with cognitive impairment and de-

drome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2001;14: mentia: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med

431– 436. 56 Horvat M, Croce R. Physical rehabilitation Rehabil. 2004;85:1694 –1704.

of individuals with mental retardation:

47 Shamas-Ud-Din S. Genetics of Down’s syn- physical fitness and information process- 66 Rimmer JH. Health promotion for people

drome and Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psy- ing. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 1995;7: with disabilities: the emerging paradigm

chiatry. 2002;181:167–168. 233–252. shift from disability prevention to preven-

48 McCallion P, McCarron M. Aging and in- tion of secondary conditions. Phys Ther.

57 Millar LA, Fernhall B, Burkett LN. Effects of

tellectual disabilities: a review of recent 1999;79:495–502.

aerobic training in adolescents with Down

literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2004;17: syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:

349 –352. 270 –274.

49 Evenhuis HM. The natural history of de-

mentia in Down’s syndrome. Arch Neurol.

1990;47:263–267.

1406 f Physical Therapy Volume 87 Number 10 October 2007

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ayurvedam For Hair Related IssuesDocument14 pagesAyurvedam For Hair Related IssuesGangadhar Yerraguntla100% (1)

- FCE Reading and Use of English - Practice Test 14Document13 pagesFCE Reading and Use of English - Practice Test 14Andrea LNo ratings yet

- PDS Syncade RADocument6 pagesPDS Syncade RAKeith userNo ratings yet

- Newton Papers Letter Nat Phil Cohen EdDocument512 pagesNewton Papers Letter Nat Phil Cohen EdFernando ProtoNo ratings yet

- Basic SCBA: Self-Contained Breathing ApparatusDocument51 pagesBasic SCBA: Self-Contained Breathing ApparatusPaoloFregonaraNo ratings yet

- Heat Shrink CoatingDocument5 pagesHeat Shrink CoatingMekhmanNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Complications of SDDocument18 pagesRespiratory Complications of SDMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy and Women's Health Promotion: ReviewDocument8 pagesPelvic Floor Physical Therapy and Women's Health Promotion: ReviewMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Balloon-Blowing Exercise On Lung Function of SmokersDocument4 pagesEffects of A Balloon-Blowing Exercise On Lung Function of SmokersMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Cancer, Physical Activity, and ExerciseDocument71 pagesCancer, Physical Activity, and ExerciseMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- How To Systematically Assess Serious Games Applied To Health CareDocument8 pagesHow To Systematically Assess Serious Games Applied To Health CareMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Dementia and Parkinson's Disease: Similar and Divergent Challenges in Providing Palliative CareDocument13 pagesDementia and Parkinson's Disease: Similar and Divergent Challenges in Providing Palliative CareMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Dementia Associated With Parkinson's Disease: ReviewDocument9 pagesDementia Associated With Parkinson's Disease: ReviewMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinsonõs Disease: W. PoeweDocument7 pagesNon-Motor Symptoms in Parkinsonõs Disease: W. PoeweMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Multidimensional Care Burden in Parkinson-Related DementiaDocument10 pagesMultidimensional Care Burden in Parkinson-Related DementiaMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Parkinsonism and Related Disorders: Joseph H. Friedman, MDDocument4 pagesParkinsonism and Related Disorders: Joseph H. Friedman, MDMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Games For Health 2014: Ben Schouten Stephen Fedtke Marlies Schijven Mirjam Vosmeer Alex Gekker EditorsDocument161 pagesGames For Health 2014: Ben Schouten Stephen Fedtke Marlies Schijven Mirjam Vosmeer Alex Gekker EditorsMónica ReisNo ratings yet

- Unit 2Document9 pagesUnit 2Quinn LilithNo ratings yet

- 2023.01.25 Plan Pecatu Villa - FinishDocument3 pages2023.01.25 Plan Pecatu Villa - FinishTika AgungNo ratings yet

- 4K Resolution: The Future of ResolutionsDocument15 pages4K Resolution: The Future of ResolutionsRavi JoshiNo ratings yet

- Catchment CharacterisationDocument48 pagesCatchment CharacterisationSherlock BaileyNo ratings yet

- Mono and DicotDocument3 pagesMono and Dicotlady chaseNo ratings yet

- Material Balance & Energy Balance - Reactor-2Document32 pagesMaterial Balance & Energy Balance - Reactor-2Xy karNo ratings yet

- Língua Inglesa: Reported SpeechDocument3 pagesLíngua Inglesa: Reported SpeechPatrick AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Updated DOTr Directory As of 29 October 2021Document9 pagesUpdated DOTr Directory As of 29 October 2021Twinkle MiguelNo ratings yet

- Cause and Effect PowerpointDocument20 pagesCause and Effect PowerpointSherly V.LizardoNo ratings yet

- View Result - CUMS Comprehensive University Management System - M.K.Bhavnagar University Powered by AuroMeera A College Management System ProviderDocument1 pageView Result - CUMS Comprehensive University Management System - M.K.Bhavnagar University Powered by AuroMeera A College Management System ProviderKiaanNo ratings yet

- The Laws of Motion ¿ ¿ Cengage LearningDocument57 pagesThe Laws of Motion ¿ ¿ Cengage LearningNguyễn Khắc HuyNo ratings yet

- Thank You For Your Order: Power & Signal Group PO BOX 856842 MINNEAPOLIS, MN 55485-6842Document1 pageThank You For Your Order: Power & Signal Group PO BOX 856842 MINNEAPOLIS, MN 55485-6842RuodNo ratings yet

- Optoelectronics Circuit CollectionDocument18 pagesOptoelectronics Circuit CollectionSergiu CristianNo ratings yet

- Tecnical Data TYPE 139 L12R / L16RDocument1 pageTecnical Data TYPE 139 L12R / L16RLada LabusNo ratings yet

- A 388 - A 388M - 03 - Qtm4oc9bmzg4tqDocument8 pagesA 388 - A 388M - 03 - Qtm4oc9bmzg4tqRod RoperNo ratings yet

- Lighting Movements-The Fox On The FairwayDocument1 pageLighting Movements-The Fox On The FairwayabneypaigeNo ratings yet

- Jotafloor: Traffic Deck SystemDocument12 pagesJotafloor: Traffic Deck SystemUnited Construction Est. TechnicalNo ratings yet

- Queueing TheoryDocument6 pagesQueueing TheoryElmer BabaloNo ratings yet

- Wednesday 12 June 2019: ChemistryDocument32 pagesWednesday 12 June 2019: ChemistryMohammad KhanNo ratings yet

- FAB-3021117-01-M01-ER-001 - Rev-0 SK-01 & 02Document91 pagesFAB-3021117-01-M01-ER-001 - Rev-0 SK-01 & 02juuzousama1No ratings yet

- Scientific Approaches For Impurity Profiling in New Pharmaceutical Substances and Its Products-An OverviewDocument18 pagesScientific Approaches For Impurity Profiling in New Pharmaceutical Substances and Its Products-An OverviewsrichainuluNo ratings yet

- Design and Modeling of Zvs Resonantsepic Converter For High FrequencyapplicationsDocument8 pagesDesign and Modeling of Zvs Resonantsepic Converter For High FrequencyapplicationsMohamed WarkzizNo ratings yet

- Radiation Physics and Chemistry: L.T. Hudson, J.F. SeelyDocument7 pagesRadiation Physics and Chemistry: L.T. Hudson, J.F. SeelyThư Phạm Nguyễn AnhNo ratings yet

- AnorexiaDocument1 pageAnorexiaCHIEF DOCTOR MUTHUNo ratings yet