Professional Documents

Culture Documents

LIT Lesson Only (Week 4)

Uploaded by

Tet BCOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

LIT Lesson Only (Week 4)

Uploaded by

Tet BCCopyright:

Available Formats

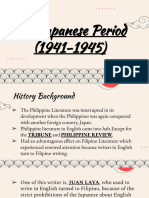

Philippine Republic, Martial Law Period and Post-Martial Law Period

New award-giving bodies came out, and one of these was the Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Award for Literature, known

to be the most prestigious and the longest-running award-giving body in the field of literature, equivalent to the world-renowned

Pulitzer Prize. By this time, the Philippine writers were producing works in English, the vernacular, and Filipino (one of the official

languages of the country and the Tagalog-based national language as promulgated by Pres. Manuel L. Quezon during the

Commonwealth Period, opposed to the Tagalog, the language spoken by the majority of dwellers in Southern Luzon). The following

names bywords in the Philippine literary scene because of their outstanding contributions:

Lazaro Francisco Wilfrido D. Nolledo

Amado V. Hernandez Wilfrido P. Virtusio

Jose Garcia Villa Ricaredo Demetillo

Alejandro G. Abadilla Virgilio Almario (aka Rio Alma)

Genoveva Edroza-Matute Efren Abueg

Claro M. Recto Rogelio R. Sikat

Paul A. Dumol Edgardo M. Reyes

Tony Perez Bienvinido A. Ramos

Emmanuel Torres Bienvinido N. Santos

Nick Joaquin (aka Quijano Manila) Kerima Polotan Tuvera

N.V.M. Gonzalez Lamberto E. Antonio

Under the administration of Roxas, Quirino, Magsaysay, Garcia and Macapagal, the writers enjoyed greater liberty in terms

of content, style, and genre. However, after the declaration of Martial Law by Marcos on September 21, 1972, the writers’ freedoms

were curtailed in much the same way as the other freedoms were suppressed. During the Martial Law years, only the government

publications continued to see print; the rest was discontinued. Anti-government and anti-Marcos writings proliferated in the form of

underground publications led by Malaya. The lives of oppositionist writers were controlled by the state. Some of them whose works

were found subversive or seditious were silenced by means of summary execution; others were illegally detained and torture. Even

after the lifting of Martial Law on January 1, 1981, the censorship of publications continued. Publishing companies that were closed

did not reopen. The literary works were much the same as those composed during the first year of the Period of the New Society

(Kilusang Bagong Lipunan or KBL). Anti-Marcos writers voice out their sentiments in the form of poems, short stories, essays, and

plays.

The assassination of Sen. Benigno Aquino on August 21, 1982 revived the nationalistic spirit in the Filipino writers. The

desire was most intense as the protest reached its climax during the EDSA revolution, the much-celebrated bloodless struggle

between the Reform the Army Movement (RAM) soldiers led by Col. Gregorio Honasan and the Marcos-loyalist soldiers as a

result of the February 1986 snap presidential polls. Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) Chief of Staff Fidel V. Ramos and

the Secretary of the Department of National Defense Juan Ponce Enrile, sided with Honasan’s group that Pres. Marcos decided to

leave the Philippines. It spelled good news to the writers who exposes about the family’s ill-gotten wealth, Imelda’s jewelry and shoe

collections, Swiss accounts, and innumerable cases of human rights’ violations.

The EDSA Revolution of 1986 was responsible for the restoration of the lost freedoms, among which was the freedom to

express one’s ideas and emotions in writing. It was this unlimited freedom that prompted feminist writers and their supporters

(GABRIELA) to speak out their views about male chauvinism, equality of rights between men and women, women’s liberation,

violation of women’s rights, etc. Similarly, LGBT writers enjoyed as much freedom and made their voices heard through their

revealing writings about discrimination, same-sex marriages, homosexual and bisexual relationships, and violation of their rights.

To inspire the Filipino artists in the different genres of art, the National Artist Awards were given to deserving individuals.

In the field of literature, the recipients of the National Artist are as follows:

Jose Garcia Villa (1973) Francisco Sionil Jose (2001)

Amado V. Hernandez (1973 Alejandro Roces (2003)

Nick Joaquin (1976) Virgilio Almario (2003)

Carlos P. Romulo (1982) Bienvinido Lumbera (2006)

Edith Tiempo (1999) Lazaro Francisco (2009)

With your group, dramatize the poem while one member reads it aloud. Make sure that certain metaphors or symbols in the

poem should stand out. Afterward, one member should explain the theme of the poem, and how this was shown in your skit.

Apo on the Wall

By BJ Patino

There’s this man’s photo on the wall

Of my father’s office at home, you

Know, where father brings his work,

Where he doesn’t look strange

Still wearing his green uniform

And colored breast plates, where,

To prove that he works hard, he

Also brought a photo of his boss

Whom he calls Apo, so Apo could,

You know, hang around the wall

Behind him and look over his shoulders

To make sure he’s snappy and all.

Father snapped at me once, caught me

Sneaking around his office at home

Looking at the stuff on his wall – handguns,

Plaques, a sword, medals, a rifle –

Told me that was no place for a boy,

Only men, when he didn’t really

Have to tell me because, you know,

That photo of Apo on the wall was already

Looking at me while I moved around,

His eyes following me like he was

That scary Jesus in the hallway, saying

I know, I know what you’re doing.

In order to appreciate the poem about martial law and former President Marcos, try to find out what older people think or feel

about martial law. Interview two people and ask them the following questions:

1. What do you remember about martial law & Ferdinand Marcos?

2. Do you think Martial Law was a good or a bad time in Philippine history? Why do you say so?

3. Why should we study this period in our history and what can we learn from this period?

You might also like

- Contemp FinalDocument25 pagesContemp FinalGibreel SHNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Lit Lesson 4Document10 pages21st Century Lit Lesson 4Melanie Jane Daan100% (1)

- Apo On The WallDocument12 pagesApo On The WallDivine RamosNo ratings yet

- 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldDocument7 pages21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldJasNo ratings yet

- 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldDocument7 pages21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldJasNo ratings yet

- 7 NationalArttist (LITERATURE)Document12 pages7 NationalArttist (LITERATURE)Victoria R. SibayanNo ratings yet

- NewDocument52 pagesNewDina ValdezNo ratings yet

- SHS 21ST4G12Document3 pagesSHS 21ST4G12Shane UgayNo ratings yet

- IAS. Kultura NG PagtutolDocument5 pagesIAS. Kultura NG Pagtutolreginaroyo25No ratings yet

- 7 Philippine Literature NewDocument40 pages7 Philippine Literature NewAngelo Bagaoisan PascualNo ratings yet

- Apo On The WallDocument15 pagesApo On The WallAlexandria Brűchweiler100% (3)

- The Rebirth of Freedom FinalDocument8 pagesThe Rebirth of Freedom FinalDonalyn Bita-olNo ratings yet

- Villegasjerome Floyd SDocument18 pagesVillegasjerome Floyd Sapi-587944514No ratings yet

- Share 21st Cen - Lit. (Module 3)Document6 pagesShare 21st Cen - Lit. (Module 3)Kei VenusaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature During The American PeriodDocument12 pagesPhilippine Literature During The American PeriodDanna Mae Terse YuzonNo ratings yet

- 04 Learners Handouts - 21st Century LiteratureDocument75 pages04 Learners Handouts - 21st Century LiteratureChristine BustamanteNo ratings yet

- Life and Works of RizalDocument4 pagesLife and Works of RizalJerica Mae GabitoNo ratings yet

- 7 Philippine LiteratureDocument48 pages7 Philippine LiteratureJuanito Jr. RafananNo ratings yet

- Japanese Period in The PhilippinesDocument45 pagesJapanese Period in The PhilippinesShalom Wenceslao74% (19)

- Horacio de La CostaDocument10 pagesHoracio de La CostaJulioNo ratings yet

- American Regime (1898-1941)Document29 pagesAmerican Regime (1898-1941)Conie Borabo PanchoNo ratings yet

- 21st Lit Module 2 National ArtistsDocument26 pages21st Lit Module 2 National ArtistsJennie KImNo ratings yet

- Literary Periods of Philippine LiteratureDocument7 pagesLiterary Periods of Philippine LiteratureJustine Airra Ondoy100% (1)

- The Third Republic ReportDocument54 pagesThe Third Republic ReportLowellyn Grezen VillaflorNo ratings yet

- Module in 21 Century Literature From The Philippines To The WorldDocument6 pagesModule in 21 Century Literature From The Philippines To The WorldSalima A. PundamdagNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet - Tonyo Pepe & PuleDocument3 pagesFact Sheet - Tonyo Pepe & Pulepaulo empenioNo ratings yet

- Prepared Module For 21ST W4Q1Document5 pagesPrepared Module For 21ST W4Q1Lielanie NavarroNo ratings yet

- Jose Garcia VillaDocument19 pagesJose Garcia VillaMyles JhayneNo ratings yet

- Analytical PaperDocument3 pagesAnalytical PaperKian VeracionNo ratings yet

- Padre Faura Witnesses The Execution of Rizal: by Danton RemotoDocument8 pagesPadre Faura Witnesses The Execution of Rizal: by Danton RemotoCabuhat, Julianna P.No ratings yet

- Lit ReviewerDocument9 pagesLit ReviewerCarie Joy UrgellesNo ratings yet

- GRP 1 American Period by MariaDocument2 pagesGRP 1 American Period by MariaMaria RamirezNo ratings yet

- Popular Poems in The PhilippinesDocument35 pagesPopular Poems in The Philippinesjunebohnandreu montanteNo ratings yet

- National Artist For LiteratureDocument17 pagesNational Artist For Literaturechristian franciaNo ratings yet

- Rizal's Family, Childhood, and Early Education ActivitiesDocument14 pagesRizal's Family, Childhood, and Early Education ActivitiesNicole Mercadejas NialaNo ratings yet

- Japanese PeriodDocument23 pagesJapanese PeriodAJ SAN JUANNo ratings yet

- Reviewer LitDocument11 pagesReviewer LitLea HaberNo ratings yet

- Nick Joaquin: Born: May 4, 1917 Place of Birth: Paco, ManilaDocument6 pagesNick Joaquin: Born: May 4, 1917 Place of Birth: Paco, ManilaSky RavenaNo ratings yet

- Midterm NotesDocument2 pagesMidterm NotesAndrea Faith RecanaNo ratings yet

- Philippine National ArtistsDocument62 pagesPhilippine National ArtistsAlexandra A. GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Coronado - ST - Padre Pio, SET ADocument3 pagesCoronado - ST - Padre Pio, SET ALucas RooweNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature in The Japanese EraDocument3 pagesPhilippine Literature in The Japanese EraRose MarieNo ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument32 pagesPhilippine LiteratureMarielley82% (11)

- Lit Lecture 1Document7 pagesLit Lecture 1Janina Pearl LocsinNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5Document10 pagesLesson 5JESSICA CALVONo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature During The Japanese PeriodDocument4 pagesPhilippine Literature During The Japanese Periodjohn reycel gacaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Arts - American Colonial Tradition (HUMSS 11-D)Document68 pagesContemporary Arts - American Colonial Tradition (HUMSS 11-D)Dulce J. Luaton100% (1)

- The American RegimeDocument7 pagesThe American RegimeMieca Dalion BaliliNo ratings yet

- American Regime LiteratureDocument36 pagesAmerican Regime LiteratureMiconNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Lesson 4: Context and Text'S MeaningDocument9 pages21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Lesson 4: Context and Text'S MeaningEdwin Peralta IIINo ratings yet

- Main Article: 2009 National Artist of The Philippines ControversyDocument9 pagesMain Article: 2009 National Artist of The Philippines Controversyjessica navajaNo ratings yet

- 21STcentury LiteratureDocument5 pages21STcentury LiteratureFheng Tan100% (2)

- American Era in Phlippine LiteratureDocument7 pagesAmerican Era in Phlippine LiteratureJoseph TobsNo ratings yet

- A.1.3 Philippine Literary History - American PeriodDocument43 pagesA.1.3 Philippine Literary History - American PeriodAnna Dalin-MendozaNo ratings yet

- Period To ActivismDocument31 pagesPeriod To ActivismJohn Ver100% (1)

- Philippine Literature During American PeriodDocument5 pagesPhilippine Literature During American PeriodMi-cha ParkNo ratings yet

- Japanese PDFDocument4 pagesJapanese PDFChristine Joy Olano CastilloNo ratings yet

- Life and Works of Jose Garcia VillaDocument12 pagesLife and Works of Jose Garcia VillaHansen Jam von MatinagnosNo ratings yet

- Living Carelessly in Tokyo and Elsewhere: A MemoirFrom EverandLiving Carelessly in Tokyo and Elsewhere: A MemoirRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

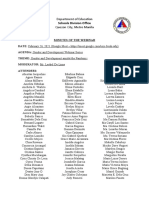

- Minutes - Gender and Development Webinar 02-26-2021Document4 pagesMinutes - Gender and Development Webinar 02-26-2021Tet BCNo ratings yet

- Lit (From Reference Book)Document1 pageLit (From Reference Book)Tet BCNo ratings yet

- Jesus T. Peralta: PhilippinesDocument3 pagesJesus T. Peralta: PhilippinesTet BC0% (1)

- LIT Lesson Only (Week 2)Document1 pageLIT Lesson Only (Week 2)Tet BCNo ratings yet

- Khatrina BonaguaDocument1 pageKhatrina BonaguaTet BCNo ratings yet

- LIT Lesson Only (Week 3)Document1 pageLIT Lesson Only (Week 3)Tet BCNo ratings yet

- LIT Lesson Only (Week 5)Document4 pagesLIT Lesson Only (Week 5)Tet BCNo ratings yet

- LIT Lesson Only (Week 1)Document1 pageLIT Lesson Only (Week 1)Tet BCNo ratings yet

- LIT Lesson Only (Week 6)Document2 pagesLIT Lesson Only (Week 6)Tet BCNo ratings yet