Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Cross-Cultural Study On Escalation of Commitment Behavior in Software Projects

Uploaded by

Rohit MishraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Cross-Cultural Study On Escalation of Commitment Behavior in Software Projects

Uploaded by

Rohit MishraCopyright:

Available Formats

A Cross-Cultural Study on Escalation of Commitment Behavior in Software Projects

Author(s): Mark Keil, Bernard C. Y. Tan, Kwok-Kee Wei, Timo Saarinen, Virpi Tuunainen and

Arjen Wassenaar

Source: MIS Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Jun., 2000), pp. 299-325

Published by: Management Information Systems Research Center, University of Minnesota

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3250940 .

Accessed: 11/09/2014 17:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Management Information Systems Research Center, University of Minnesota is collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to MIS Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keilet al./Culture&Escalationof Commitment

A CROSS-CULTURALSTUDY ON ESCALATION

OF COMMITMENTBEHAVIORIN

SOFTWAREPROJECTS1

By: Mark Keil Virpi Tuunainen

Department of Computer Information Department of Business Information

Systems Systems

Georgia State University Helsinki School of Economics and

Atlanta, GA 30302-4015 Business Administration

U.S.A. FIN-00100 Helsinki

mkeil@gsu.edu FINLAND

Tuunainen@HKKK.Fi

Bernard C. Y. Tan

Department of Information Systems Arjen Wassenaar

National University of Singapore Department of Information Systems

Singapore 119260 Management

REPUBLICOF SINGAPORE University of Twente

btan@comp.nus.edu.sg 7500 AE Enschede

THE NETHERLANDS

Kwok-Kee Wei d.a.wassenaar@sms.utwente.nl

Department of Information Systems

National University of Singapore

Singapore 119260 Abstract

REPUBLICOF SINGAPORE

weikk@comp.nus.edu.sg

One of the most challenging decisions that a

Timo Saarinen manager must confront is whether to continue or

Department of Business Information abandon a troubled project. Published studies

Systems suggest that failing software projects are often

Helsinki School of Economics and allowed to continue fortoo long before appropriate

Business Administration management action is taken to discontinue or

FIN-00100 Helsinki redirect the efforts. The level of sunk cost asso-

FINLAND ciated with such projects has been offered as one

SAARINEN@.HKKK.FI explanation for this escalation of commitment

behavior. Whatpriorstudies failto consideris how

concepts from risk-taking theory (such as risk

'KalleLyytinen

was the acceptingsenioreditorforthis propensity and risk perception) affect decision

paper. makers' willingness to continue a project under

MISQuarterlyVol.24 No. 2, pp. 299-325/June2000 299

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keilet al./Culture&Escalationof Commitment

conditions of sunk cost. To better understand commitment"behavior2 (Brockner 1992) in which

factors that may cause decision makers to con- failing projects are permittedto continue and good

tinue such projects, this study examines the level money is thrown after bad (Garland 1990).3 In

of sunk cost together with the risk propensity and recent years, researchers have drawn upon

risk perception of decision makers. These factors escalation of commitment literatureto understand

are assessed for cross-cultural robustness using

why software projects are often continued for so

matching laboratory experiments carried out in

three cultures (Finland, the Netherlands, and long before appropriate corrective action is taken

to abandon or redirect them (e.g., Drummond

Singapore).

1996; Keil 1995; Keil, et al. 1995a; Newman and

Sabherwal 1996).

Witha wider set of explanatory factors than prior

studies, we could account for a higher amount of While escalation of commitment behavior is a

variance in decision makers' willingness to

general phenomenon that can occur with any type

continue a project. The level of sunk cost and the of project, software projects may be very

risk perception of decision makers contributed

susceptible to this problem. When a software

significantly to their willingness to continue a project is underway, the intangible nature of its

project. Moreover, the risk propensity of decision products (Abdel-Hamidand Madnick1991) makes

makers was inversely related to risk perception. it difficult to obtain accurate estimates of the

Thisinverse relationshipwas significantlystronger proportion of work completed. This difficulty

in Singapore (a low uncertaintyavoidance culture) manifests itself in the "90%complete syndrome,"4

than in Finland and the Netherlands (high uncer- which may promote escalation of commitment

tainty avoidance cultures). These results reveal behavior by giving a false perception that suc-

that some factors behind decision makers'willing- cessful project completion is near. Besides the

ness to continue a project are consistent across difficultyof measuring progress, software projects

cultures while others may be culture-sensitive. also tend to have volatile requirements (Abdel-

Hamidand Madnick1991; Zmud 1980) that cause

Implications of these results for further research

and practice are discussed. project scope to change frequently. Projects that

are subjected to such volatilityare more difficultto

manage and control. The mismanagement of

Keywords: Software project management, esca- software projects can lead to situations in which

lation of commitment behavior, sunk cost, risk

projects continue to absorb resources withoutever

propensity, riskperception, uncertaintyavoidance delivering the intended benefits (Keil 1995). To

alleviate such wasteful practices, managers need

ISRL Categories: EE, EE01, EE0101, EE06,

EL0202

2Thisbehaviordoes notnecessarilyimplyan increasing

rate of investmentover time. Rather, it refers to a

growthin cumulativeinvestmentsovertime.

Introduction

3Throwing good moneyafterbad(oftencalled"thesunk

cost effect") represents one of several theoretical

One of the most challenging decisions confronting perspectivesthatexplainwhyescalationof commitment

managers aroundthe world is whether to continue behavioroccurs (forgood reviews,see Brockner1992;

Staw 1997;Staw and Ross 1987). Thispaperadoptsa

funding a project when its prospects for success sunk cost perspective on escalation of commitment

are questionable. Every day, managers have to behavior.Many studies have yielded evidence sup-

make such decisions on projects that vary tre- portingescalation of commitmentbehaviorbut a few

studies have raiseddoubtsaboutthe reproducibility

of

mendously in type and size. Very often, the this phenomenon(e.g., Armstrong1996).

amount of money already spent on a project (level

of sunk cost), along with other factors, can bias 4Thissyndromerefersto the tendencyforestimatesof

workcompletedto increase steadilyuntila plateauof

managers toward continuing to fund the project. 90% is reached. Software projectstend to be "90%

In many instances, this results in "escalation of complete"forhalfthe entireduration(Brooks1975).

300 MISQuarterly

Vol.24 No. 2/June2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keilet al./Culture&Escalationof Commitment

to know more about factors that influence their ignore the level of sunk cost when making such

willingness to continue a project so that they can decisions. Besides showing that the sunk cost

minimize unnecessary expenditures and cut their effect may be a critical factor contributing to

losses when appropriate. Prior research has escalation of commitment in software projects

shown that sunk cost is one such factor (Garland (e.g., Keil et al. 1995b; Mann 1996), this review

1990). revealed that the sunk cost effect may vary across

cultures (e.g., Chow et al. 1997; Keil et al. 1995a;

This paper has two objectives. First, it introduces Sharp and Salter 1997).

and tests a richertheoretical model than has been

examined previously in order to better explain

decision makers' willingness to continue a soft-

ware project. While previous studies have docu- Limitations of Previous

mented the sunk cost effect, there has been no Sunk Cost Studies

attempt to develop a theoretical model that

In reviewing the empirical literature on the sunk

incorporates this effect withinthe broader context

of decision making under conditions of risk and cost effect, two obvious limitations become

uncertainty. The proposed model extends existing apparent. First, previous studies have lacked an

models of escalation of commitment behavior by underlying theoretical model that can help to

incorporating concepts from risk-taking theory. explain the sunk cost effect. Aside from vague

Besides level of sunk cost, a commonly-tested references to prospect theory, there has

situational factor, this model includes risk pro- apparently been no attempt to develop a robust

theoretical model of the sunk cost effect.5

pensity and risk perception, two individualfactors

from risk-takingtheory, which may affect decision Instead, priorstudies have manipulated the level

makers' willingness to continue a project (Singer of sunk cost, usually as the sole independent

and Singer 1986; Sitkin and Pablo 1992). variable, to assess its impact on decision makers'

willingness to continue a project, the dependent

variable. Such an approach has yielded simple

Second, this paper attempts to shed light on how

cross-cultural differences may affect decision models that do not incorporate intervening vari-

makers'willingness to continue a software project. ables and cannot be analyzed using multivariate

Prior research has suggested that the sunk cost approaches. Perhaps as a result of this, the

effect does vary across cultures but the reasons amount of variance explained in the dependent

behind such variations are not clear (Keil et al. variable has been low. For example, Garland's

1995a). Since risk propensity and risk perception (1990) analysis of variance model could only

are related to uncertainty avoidance, a cultural account for 8.5% of the variance in the dependent

factor that distinguishes people from different variable. Similarly, Keil et al. (1995a) could ex-

cultures in terms of their risk-taking tendency plain less than 14% of the variance in the depen-

dent variable. To gain a better understanding of

(Hofstede 1991), the proposed model is tested

with subjects from different cultures to identify the sunk cost effect, a stronger theoretical model

cross-cultural variations. that can account for more of the variance in

decision makers' willingness to continue a project

is needed. This study integrates the sunk cost

literaturewith the risk-takingliteratureto develop

Prior Literatureon and test a theoretical model.

Sunk Cost Effect

Contemporary financial theory recommends that 5Prospecttheory posits that the framingof decision

level of sunk cost should not be considered when situationsaffects decision-makingbehaviorand that

deciding whether to continue or abandon a project gains and losses are evaluatedwith respect to some

decisionframe.People tend to be more risk-seekingif

(Bonini 1977; Howe and McCabe 1983). However, the decisionsituationis framedas a choice amongloss

a review of the empirical literature (see Table 1) scenarios (Kahnemanand Tversky1979;Tverskyand

revealed that decision makers find it difficult to Kahneman1981),whichis alwaysthe case forstudies

on the sunk cost effect.

MISQuarterlyVol.24 No. 2/June2000 301

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

=Ii.11[U ~mIl

II I [*1E '4* 1.1. U1IHlUetU~I1

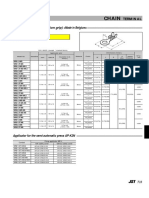

Study Key findings

Arkes and Blumer Level of sunk cost can influence people across a wide variety of decision

(1985) contexts.

Northcraftand Neale People fail to consider opportunitycosts and frame their decisions as a

(1986) choice between losses. Makingopportunitycosts explicit can alter framing

of decisions and reduce sunk cost effect.

Garland (1990) There is a linear sunk cost effect based on budget already invested. Higher

percentages of sunk cost can lead to greater willingness to continue with a

course of action.

Garland et al. (1990) De-escalation of commitment can occur when sunk costs are positively

correlated with unambiguous negative feedback.

Garland and Newport Absolute sunk cost is actual dollar amount already expended. Relative

(1991) sunk cost is percentage of total budget already spent. Relative rather than

absolute sunk cost affects people's likelihoodto commit additional funds to

some action.

Simonson and Nye Accountabilitycan alleviate susceptibility to decision errors and reduce the

(1992) sunk cost effect.

Conlon and Garland People's willingness to continue a project are driven by level of project

(1993) completion ratherthan level of sunk cost per se.

Heath (1995) People are likely to escalate commitment when they fail to set a budget or

when expenses are difficultto track.

Keil et al. (1995a) Sunk cost effect can be reduced if people have an alternative project for

which they can spend their money. Finnish subjects have a smaller ten-

dency to escalate their commitment at high levels of sunk cost compared to

U.S. subjects.

Keil et al. (1995b) People are more apt to justify their decisions to continue a project based on

level of sunk cost ratherthan level of completion.

Staw and Hoang (1995) Amount of money spent to acquire NBA players influences how much

playing time players get and how long players stay with NBA franchises,

controllingfor players' on-court performance.

Mann (1996) Informationsystems auditors report that level of sunk cost was used as a

justificationfor continuing in about 45% to 50% of software projects that

escalate.

Chow et al. (1997) Chinese subjects have a greater tendency to escalate their commitment on

projects than U.S. subjects. Chinese subjects may be more concerned

about saving face, due to their culture, and so more committed to their

earlier decisions. Alternatively,Chinese subjects may be simply more

willingto take risk.

Sharp and Salter (1997) Asian managers are more risky than NorthAmerican managers when

making decisions involving potential long-term benefits for the firm, but

Asian managers are less risky than NorthAmerican managers when

making decisions involving short-term financial gains. Asian managers may

have a longer-term orientation than NorthAmerican managers when

making decisions.

302 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

Second, there have been few attempts to explore Risk-taking theory suggests that risk perception

cross-cultural variations of the sunk cost effect. and risk propensity of individuals affect their risk

The few studies that have been carried out behavior (Sitkin and Pablo 1992). Given that the

suggest that there may be cross-cultural dif- decision to continue a software project is risk-

ferences in terms of decision makers' willingness seeking behavior, risk perception and risk

to continue a project. Although various retro- propensity are likely to affect decision makers'

spective explanations have been offered for these willingness to continue a project.6 Risk perception

findings, it is not possible to draw any firm is "a decision maker's assessment of the risk

conclusions because of the lack of a theoretical inherent in a situation" (Sitkin and Pablo 1992).

model that can account for such cross-cultural Based on our definition of risk, an event is

differences. In other words, it is not known considered risky if its outcome is uncertain and

whether the observed effects were actually due to may result in a loss (Barkiet al. 1993; Mellers and

cross-cultural differences, and if so, how these Chang 1994). Risk propensity is the tendency of

differences actually led to the observed results. a decision maker to take riskyactions (Kogan and

Using a theoretical model with culturally-sensitive Wallach 1964; Sitkin and Pablo 1992).7

constructs from risk-taking theory, this study

seeks to better understand how culturemoderates Since risk propensity and risk perception are

decision makers' willingness to continue a project. individualfactors, they are likely to be shaped to

some extent by a decision maker's cultural

background. A cultural factor related to risk

propensity and risk perception is uncertainty

Theoretical Model avoidance, defined as the extent to which people

of a culture feel threatened by unknown situations

and Hypotheses (Hofstede 1991). High uncertainty avoidance

cultures have a majority of people who accept

To builda theoretical model that can explain more only familiar risk and fear ambiguous situations.

of the variance in decision makers' willingness to Conversely, people from low uncertainty avoid-

continue a project, additional factors that poten- ance cultures tend to be comfortable with ambi-

tially contribute to this behavior must be consi- guous situations and unfamiliarrisk. Given their

dered and incorporated. Such factors have been greater comfort with risk, people from low uncer-

discussed in risk-takingtheory, which posits that tainty avoidance cultures may have higher risk

risk taking has positive and negative conse- propensity. Since they fear ambiguous situations

quences (Arrow1965). Although Charette (1989) less, people from low uncertainty avoidance cul-

defines software riskalong risk-theoreticlines, the tures may also have lower risk perception. Hence,

software risk management literature has largely a theoretical model that includes individualfactors

focused on negative outcomes (Barkiet al. 1993; in its explanation of decision makers' willingness

Lyytinen et al. 1998). This is because continuing

a software project involves uncertainty arising

from inaccurate estimation of projectprogress and

6In some organizationalcontexts, the decision to

volatile project requirements (Abdel-Hamid and continuea softwareprojectmaybe risk-aversebehavior.

Madnick 1991). The greater uncertainty asso- This issue is explored as a possibilityfor further

ciated with continuing, rather than terminating, a research.However,it does not applyin this study. The

mean score for Riskper3 and Riskper4 (see the

software project is a riskthat often leads to nega-

appendix)is 3.61 on a scale of 1 to 5, showing that

tive outcomes. Consistent with this focus, risk is subjects in this study had indeed considered the

defined as the non-zero probability that some decisionto continuea projectas risk-seekingbehavior.

undesirable outcomes will occur. This definition

7Somescholarshave conceptualizedriskpropensityas

agrees with the risk-takingliterature,which views a generalpersonalitytraitthatcauses decision makers

uncertain courses of action (e.g., continuing a to exhibitconsistentrisk-seekingor risk-aversetenden-

project in the hope that it will be successful) as cies across situations (e.g., Harnettand Cummings

risk-seeking behavior and certain courses of 1980). While agreeing that risk propensity is a

action (e.g., terminating a project) as risk-averse personalitytrait,others have suggested that an indivi-

dual's risk propensity is situation-specific (e.g.,

behavior. MacCrimmon andWehrung1990).

MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000 303

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

Note: Paths in bold are hypothesized to be culturallysensitive.

_I~]L~II~t~ll~~l

I~I~I=

to continue a project needs to be assessed for This leads to over-optimism, which lowers the risk

cross-cultural variations. perception of decision makers. Conversely, risk-

averse decision makers tend to focus on negative

To overcome limitations of previous sunk cost outcomes and disregardpositive outcomes. These

studies, we propose a theoretical model to decision makers may be very affected by software

account for decision makers' willingness to risk,which often results in negative outcomes, and

continue a project (see Figure 1). It incorporates overestimate the probabilityof a loss (Schneider

level of sunk cost (a situational factor) as well as and Lopes 1986). This results in over-pessimism,

risk propensity and risk perception (two individual which elevates the risk perception of decision

makers.

factors). As in previous studies, decision makers'

willingness to continue a project reflects escala-

tion of commitment behavior. In this model, each In every culture, there are people with high and

path is a hypothesis to be tested. Given that people with low risk propensity because risk

certain paths (those in bold) may be moderated by propensity is a personalitytrait,8butthe translation

culture, the model must be validated using data of risk propensity into risk perception may be

from several culturalsettings. moderated by culture. People from low uncertainty

avoidance cultures tend to be more comfortable

with ambiguous situations and have less fear for

The empirical literaturesuggests that risk propen-

negative outcomes (Hofstede 1991). Over time,

sity may impact risk perception (Brockhaus 1980;

they may have developed liberal lower limits9for

Vlek and Stallen 1980). When people have high

risk propensity, they tend to be more risk-seeking

in a given situation. Such risk-seeking decision

makers are more likely to focus on positive out- 8However,average riskpropensityof an entirepopula-

tion of people tends to be higherfor low uncertainty

comes and pay less attention to negative out- avoidance cultures and lower for high uncertainty

comes. Since software risk often results in nega- avoidancecultures.

tive outcomes, these decision makers may ignore

software risk and underestimate the probabilityof 9McCain(1986) showed thatpeople didexhibitvarying

a loss (Brockhaus 1980; Vlek and Stallen 1980). limitsin termsof theirtendenciesto escalate a project.

Giventhe strongcausal relationshipbetweenriskper-

304 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keilet al./Culture&Escalationof Commitment

risk perception. Hence, people with high risk perception is low. Their result provides support for

propensity may have very low risk perception the inverse relationship between risk perception

while people with low risk propensity may still and decision makers' willingness to continue a

have high risk perception. Since risk perception project.

varies greatly with risk propensity, the result is a

strong path coefficient. Conversely, people from H2: In all cultures, risk perception will

high uncertaintyavoidance cultures tend to avoid have a significant inverse effect on

ambiguous situations and fear negative outcomes willingness to continue a project.

(Hofstede 1991). Over time, they may have

developed conservative lower limits for risk Within a given context, decision makers may

perception. Hence, people with high risk propen- exhibit relatively stable tendencies to either take

sity may not have very low risk perception or avoid risky actions depending on their risk

whereas people with low risk propensity may still propensity (Harnett and Cummings 1980; Kogan

have high risk perception. If risk perception does and Wallach 1964; Sitkin and Pablo 1992).

not vary greatly with risk propensity, the result is Therefore, risk propensity may be a determinant

weak path coefficient. In short, uncertaintyavoid- of decision makers' behavior when they are

ance may magnify the inverse relationship confronted with risky choices, including decisions

between risk propensity and risk perception. about whether or not to continue a project. An

issue that remains unresolved, however, is the

HI: In all cultures, risk propensity will extent to which the relationship between risk

have a significant inverse effect propensity and risk behavior is mediated by risk

on risk perception. perception. Ithas been observed that people differ

in risk propensity (Fishburn 1977; MacCrimmon

H1a: The inverse relationship between and Wehrung 1990), but there is little consensus

risk propensity and risk percep- about how it affects risk behavior. Based on an

tion will be stronger in cultures extensive review of the risk literature, Sitkin and

lower on uncertainty avoidance. Pablo (1992) propose a theoretical model in which

there is a direct effect of risk propensity on risk

Few empirical studies have directly manipulated behavior. In an experiment, however, Sitkin and

risk perception. However, many studies have Weingart (1995) found no direct effect of risk

examined the impact of variables (e.g., task propensity on risk behavior. Instead, they found

nature, problem domain familiarity, and self- the effect of risk propensity on risk behavior to be

efficacy) that are thought to have exerted an fully mediated by risk perception. Given that the

indirecteffect on risk behavior through changes in theoretical literaturesuggests a direct effect of risk

riskperception (Kruegerand Dickson 1994; Slovic propensity on risk behavior, further research is

et al. 1982). Priorresearch suggests that decision warranted to determine if such an effect is direct,

makers tend to exhibit risk-averse behavior when mediated, or partiallydirectand partiallymediated.

risk perception is high and risk-seeking behavior

when risk perception is low (e.g., March and H3: In all cultures, risk propensity will

Shapira 1987; Staw et al. 1981). As discussed have a significant direct effect on

above, a decision to continue a software project is

willingness to continue a project.

a kind of risk-seeking behavior. Therefore, deci-

sion makers tend to be more willingto continue a

project when their risk perception is low. Sitkin Existing evidence concerning the sunk cost effect

and Weingart (1995) reportthat decision makers (e.g., Arkes and Blumer 1985; Garland 1990; Keil

tend to make more riskydecisions when their risk et al. 1995a) suggests that as the level of sunk

cost increases, the likelihoodthat decision makers

will continue a project increases correspondingly.

While this behavior is consistent with the kind of

ceptionandriskbehavior(Sitkinand Weingart1995),it cognitive bias explained by prospect theory

is plausiblethatthe varyinglimitsof peopleto escalate (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Tversky and

a projectresultfromdifferencesin theirlimitsfor risk Kahneman 1981), another explanation is that an

perception.

MISQuarterlyVol.24 No. 2/June2000 305

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keilet al./Culture&Escalationof Commitment

inverse relationship exists between level of sunk a direct relationship between level of sunk cost

cost and risk perception. Such a relationship may and decision makers' willingness to continue a

exist, for example, if decision makers equate level project. However, these studies have never tested

of sunk cost with level of project completion. This the possible mediating role of risk perception (as

possibility cannot be ignored because level of represented by H4 and H4a). Therefore, to assess

sunk cost and level of projectcompletion are often whether this relationship is direct, mediated, or

manipulated jointly in experiments. A higher partially direct and partially mediated, it is

perceived level of projectcompletion may result in necessary to add a hypothesis asserting that level

a lowering of risk perception. Ifthis explanation is of sunk cost has a direct effect on decision

true, higher levels of sunk cost should lower risk makers' willingness to continue a project.

perception of decision makers, causing them to be

more willing to continue the project. Research is H5: In all cultures, level of sunk cost will

warrantedto determine if the commonly observed have a significant direct effect on

relationship between level of sunk cost and willingness to continue a project.

decision makers' willingness to continue a project

is mediated by risk perception.

This translation of level of sunk cost into risk Design and Methodology

perception may be moderated by culture. As dis-

cussed earlier, people from low uncertainty Consistent with previous studies that investigated

avoidance cultures may have developed liberal decision makers' willingness to continue a project,

lower limits for risk perception over time. Thus, laboratoryexperiments were used to address the

people confronted with a high level of sunk cost research questions. This approach allowed extra-

may have very low risk perception while people neous variables to be controlled so that causal

confronted with a low level of sunk cost may still relationships between constructs inthe theoretical

have high risk perception. Since risk perception model could be tested with minimal interference

varies greatly withthe level of sunk cost, the result from extraneous variables. Therefore, results of

is a strong path coefficient. Also, people from high this study should have strong internal validity.

uncertainty avoidance cultures may have deve- Each experiment had a single-factor, four-cell

loped conservative lower limitsfor risk perception design (each cell corresponding to a differentlevel

over time. Thus, people confronted with a high of sunk cost, presented to subjects in the form of

level of sunk cost may not have very low risk a scenario).

perception whereas people confronted with a low

level of sunk cost may still have high risk per-

ception. When risk perception does not vary Cultures

greatly with level of sunk cost, the result is a weak

path coefficient. Thus, uncertaintyavoidance may The work of Hofstede (1991) and Keil et al.

magnify the inverse relationship between level of (1995a) suggested that people from different

sunk cost and risk perception. cultures might engage in different risk behavior

when exposed to the same decision situation. As

H4: In all cultures, level of sunk cost will discussed above, people from low uncertainty

have a significant inverse effect on avoidance cultures might have developed a lower

risk perception. limitfor risk perception, and thus be more willing

to continue a project,than people fromhigh uncer-

H4a: The inverse relationship between tainty avoidance cultures. To assess the cross-

level of sunk cost and risk per- cultural hypotheses in our theoretical model,

ception willbe stronger in cultures matching experiments were conducted in three

lower on uncertainty avoidance. cultures (Finland, the Netherlands, and Singa-

pore) which differ on uncertainty avoidance.

Previous studies (e.g., Arkes and Blumer 1985; Finland, the Netherlands, and Singapore have

Garland 1990; Keil et al. 1995a) have suggested uncertainty avoidance scores of 59, 53, and 8,

306 MISQuarterly

Vol.24 No. 2/June2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

respectively (Hofstede 1991).1' These differences Finnish and Dutch versions of the scenario were

on uncertaintyavoidance were assessed using a created respectively. In these instances, the

manipulationcheck (described below). scenario was firsttranslated into Finnish or Dutch

by a person from the respective cultures. Next, it

These three cultures were selected for several was back-translated into English by another

reasons. First, the bulk of priorwork in this area person fromthe respective cultures. Based on this

had been carried out in the U.S. and it would be double translationprocess, minorcorrections were

interesting to see if earlier results apply in other made to the Finnish and Dutch versions of the

cultures. Second, people from these three scenario to ensure that the meanings of all

cultures have high literacy levels and comparable elements of the scenario had been preserved

language skills because they were educated in during translation.

English and one other major language. Third,

these three cultures represent developed

countries, each with a nation-wide technology Procedure

infrastructureand a fast-growing computer soft-

ware industry.

Subjects were told that this was an experiment on

business decision making and that their answers

would remain anonymous. They were reminded

Scenario that their participation was voluntary and those

who did not wish to participate could leave. More

The experimental scenario and manipulations than 95% of all subjects from each culture chose

used in this study were identical to those to participate. In each culture, participating

employed by Keil et al. (1995a). Subjects were subjects were randomly assigned to one of four

asked to play the role of president of a small treatment conditions (each representinga different

level of sunk cost). The experimental procedure

computer software company that had been

consisted of two parts. In the first part, subjects

developing a software product for external sale. received a copy of the scenario corresponding to

After receiving information on the level of sunk

their respective treatment conditions. They were

cost, subjects were told that another company had asked to read the scenario and indicate the

just started marketing a similar software package probabilitythat they would be willing to continue

that was reported to have more functionalityand with the project. Inthe second part, subjects were

greater ease of use. Based on this information, asked to complete a questionnaire that measured

subjects were asked to provide an indication of their risk propensity and risk perception, and

their willingness to continue the software project. collected their demographic information(gender,

Four versions of this scenario, each corres- age, and years of work experience).

ponding to a different level of sunk cost in relation

to the total budget, were provided to the subjects.

This way, the level of sunk cost became a

manipulated factor. Subjects

A total of 536 subjects (185 from Finland, 121

English versions of the scenario were used in

from the Netherlands, and 230 from Singapore)

Singapore. In Finland and the Netherlands,

completed this study. Subjects were under-

graduate and master's students enrolled in an

introductory information systems course at a

10Hofstede's avoidancescores for53

(1991)uncertainty university in their respective countries. Keil et al.

culturesrangefrom8 (Singapore)to 112 (Greece).The

factthatFinlandandthe Netherlandshaveclose uncer- (1995a) reportedthat undergraduate and master's

students exhibited no significant differences in

taintyavoidancescores does notwarrantthe exclusion

of eitherculturefromthis study because bothcultures their willingness to continue a project. Since this

differ on factors other than uncertaintyavoidance study used the same scenario as Keil et al.

(Hofstede 1991; Trompenaarsand Hampden-Turner (1995a), undergraduate and master's students

1998).Currentliteraturehas notbeen conclusiveabout were used to increase generalizability of the

whichculturalfactors actuallyaffect decision makers'

willingnessto continuea project. results.

MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000 307

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

T-tests revealed no significant differences The level of sunk cost was a construct mani-

between undergraduate and master's students on pulated at four different levels (15%, 40%, 65%,

any construct in the theoretical model. While the and 90% of the total budget) using four versions of

use of students as subjects might limit the the same scenario (Keilet al. 1995a). Willingness

generalizability of the results to organizational to continue a projectwas a construct measured by

decision makers (Hughes and Gibson 1991), there asking subjects, after they had read their task,

was some support for using students as surro- how likely were they to continue with the project

gates for managers, particularlywhen the tasks (see the appendix). The exact wording of this

being studied involved human decision making question was similar to that used in numerous

(Ashton and Kramer1980), which was the case in other studies (e.g., Garland 1990; Keil et al.

this study. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics 1995a).

on the demographic informationof subjects.1

Constructs and Questions Analyses and Results

The riskpropensity construct was measured using Given the large sample of subjects used in this

a single question taken from an established port- study, a very strict significance level of 0.01 was

folio of risk measures developed by MacCrimmon used for all statistical tests.'4

and Wehrung (1985) (see the appendix).'2 The

riskperception constructwas measured using four

questions specifically designed for this study (see Manipulationand Control Checks

the appendix). These questions were grounded in

the risk-takingliterature.Two questions assessed The manipulation on uncertainty avoidance was

the level of perceived risks directly. Two other checked based on three questions (see the

questions assessed perceived probability of

appendix) from Hofstede (1980). People from high

success, which contributed indirectly to risk

uncertainty avoidance cultures are likely to value

perception (Barkiet al. 1993; Mellers and Chang

security of employment, clearly prescribed (rather

1994).13 than freedom of) job approach, and stable job

nature using existing skills (rather than changing

11Sincethe ratioof males to females variedsomewhat job nature requiringnew skills). An F-test showed

across subjectgroups,we firstconducteda separate that uncertainty avoidance differed among the

PLS analysis for the combineddataset and for each three cultures (F = 305.86, p < 0.01), confirmedby

cultureto see whether gender helped to shape the a non-parametricKruskal-Wallistest (X2= 296.49,

results.Ineach case, resultsformale and femalesub-

groupsweresimilarto theoverallmodel,suggestingthat p < 0.01). Singapore subjects (mean = 1.60, std

genderdidnot affectthe overallresults.We conducted dev = 0.44) had lower uncertaintyavoidance than

similaranalysesforage andworkexperiencebysplitting Dutch subjects (mean = 2.37, std dev = 0.39) and

the dataforthe combineddataset andforeach culture Finnish subjects (mean = 2.60, std dev = 0.44).

into two subsets using the median.Again,resultsfor

each subset were the same as the overall results. The subjects from these three cultures appeared

Therefore, we concluded that these demographic to differ on uncertaintyavoidance in the direction

variableswerenotsignificantfactors.Hence,we present suggested by Hofstede (1991).

the findingswithoutbreakingdownthe samples further

by gender,age, or workexperience.

12Atthe timeourexperimentswereconducted,we were

unableto identifya multi-itemmeasureforriskpropen-

sitythathadgood psychometricproperties.Single-item directlyassess probability

of loss and directlyassess

measures may pose theoreticaldifficulties.However, perceivedrisk(whichcapturedboththe magnitudeand

this does not render results of structuralequation componentsof risk).

probability

modelinganalysisinvalid(Hairet al. 1998).

14Whensample sizes are large,statisticaltests can be

3Risk is often defined as a combinationof the verysensitiveandmaydetectspuriouseffects.Oneway

magnitudeand probability

of loss. Ourquestionsdidnot to overcome this problemis to use a very strict

directlyassess magnitudeof loss. However,they did significancelevelfordataanalyses (Hairet al. 1998).

308 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

E16JINIiJ mule!. I 1 sill IU 131leJil itU[eJ life] III 6] [Ie. I

Gender

Age in Years Work Experience in Years

Culture Mean (std dev) Mean (std dev) Males Females

Combined 21.45 (2.91) 1.26 (2.28) 59.7% 40.3%

Finland 22.46 (4.05) 2.62 (3.18) 40.0% 60.0%

The Netherlands 19.22 (1.71) 0.85 (1.59) 80.2% 19.8%

Singapore 21.81 (1.21) 0.38 (0.57) 64.8% 35.2%

Control checks were carried out on the subject 1982). Given that this study is an early attempt to

demographics for each culture. Kruskal-Wallis advance a theoretical model on decision makers'

tests showed that the gender ratio of subjects did willingness to continue a software project, PLS

not differ across the four levels of sunk cost for can be used to analyze the data. Many prior

each culture. F-tests revealed that age, work studies on informationsystems have used PLS to

experience, and riskpropensity of subjects did not test early versions of theoretical models (e.g.,

differ across the four levels of sunk cost for each Igbariaet al. 1994; Thompson et al. 1991). In this

culture. study, PLS-Graph Version 2.91 (Chin 1994) was

used.

PLS Analyses

Measurement Model

Partial least squares (PLS) is an advanced statis-

tical method that allows optimal empiricalassess- The strength of the measurement model can be

ment of a structural (theoretical) model together demonstrated through measures of convergent

with its measurement model (Wold 1982). The and discriminant validity (Hair et al. 1998). Con-

structural model consists of a network of causal vergent validity is normally assessed using three

relationships linkingmultiple constructs while the tests: reliabilityof questions, composite reliability

measurement model links each construct with a of constructs, and variance extracted by con-

set of indicators (typically questions) measuring structs (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Discriminant

that construct. PLS is superior to traditionalstatis- validitycan be assessed by looking at correlations

tical methods (e.g., factor analysis, regression, among questions (Fornell and Larcker 1981) as

and path analysis) because it assesses the well as variances of and covariances among

measurement model within the context of the constructs (Igbaria et al. 1994).

structural model. To do so, PLS first estimates

loadings of indicators on constructs and then Risk perception was a perceptual construct

estimates causal relationships among constructs measured using multiplequestions so it had to be

iteratively(Fornell 1982). assessed for convergent validity. Reliability of

these questions was assessed by examining the

PLS was selected to test the hypotheses for two loading of each question on the risk perception

reasons. First, it is not contingent upon data construct. More evidence on reliabilitycould be

having multivariate normal distributions and obtained from the correlation between each ques-

intervalnature (Fornelland Bookstein 1982). This tion and the risk perception construct. In order for

makes PLS suitable for handling manipulated the shared variance between each question and

constructs such as level of sunk cost. Second, it the risk perception construct to exceed the error

is appropriate for testing theories in the early variance, the reliability score for the question

stages of development (Fornell and Bookstein should be at least 0.707. However, a reliability

MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000 309

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

I I

Question Loading on Question-Construct

Culture Question Construct Correlation

Combined Riskperl 0.88 0.82

Riskper2 0.86 0.81

Riskper3 0.71 0.77

Riskper4 0.69 0.76

Finland Riskperl 0.91 0.85

Riskper2 0.90 0.85

Riskper3 0.57 0.64

Riskper4 0.72 0.79

The Netherlands Riskperl 0.75 0.62

Riskper2 0.57 0.62

Riskper3 0.79 0.81

Riskper4 0.76 0.82

Singapore Riskperl 0.88 0.79

Riskper2 0.88 0.79

Riskper3 0.71 0.81

Riskper4 0.69 0.79

score of at least 0.5 might be acceptable if some adequate reliabilityfor the combined dataset and

other questions measuring the same construct for each culture (see Table 4). PLS computed the

had high reliabilityscores (Chin 1998). Given that variance extracted by the riskperception construct

all questions had reliabilityscores above 0.5, and based on the extent to which its four questions

most questions had reliabilityscores exceeding tapped into the same underlying construct (Chin

0.707 (see Table 3), the questions measuring risk 1998). A score of 0.5 indicates acceptable level of

perception had adequate reliabilityfor the com- variance extracted (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

bined dataset and for each culture. Other informa- Based on this criterion, the risk perception

tion systems studies employing PLS had also construct had an acceptable level of variance

used 0.5 as an indicationof reliabilityof questions extracted for the combined dataset and for each

(e.g., Igbariaet al. 1994; Thompson et al. 1991). country (see Table 4). Variance extracted was

computed as follows (Fornell and Larcker1981):

PLS took into account relationships among

constructs when computing composite reliability rA2

scores for the risk perception construct (Chin Variance extracted =

1998). Additionalevidence on reliabilityof the risk :Ai2 + (1 - A2)

perception construct was obtained by calculating

where A = loading of question i on the

Cronbach's alpha. A score of 0.7 indicates

construct

adequate reliability of constructs, although a

slightly lower score might be acceptable for

Risk propensity and risk perception were percep-

exploratory research (Hairet al. 1998). Based on

this criterion, the risk perception construct had tual measures so they had to be assessed for dis-

criminantvalidity.Correlationsbetween all pairs of

310 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

Culture Composite Reliability Cronbach's Alpha Variance Extracted

Combine 0.87 0.80 0.62

Finland 0.86 0.79 0.62

The Netherlands 0.81 0.70 0.52

Singapore 0.87 0.81 0.63

Culture Question Riskper1 Riskper2 Riskper3 Riskper4 Riskprop

Combined Riskperl 1.00

Riskper2 0.79 1.00

Riskper3 0.44 0.36 1.00

Riskper4 0.36 0.40 0.67 1.00

Riskprop -0.22 -0.17 -0.17 -0.10 1.00

Finland Riskperl 1.00

Riskper2 0.82 1.00

Riskper3 0.39 0.26 1.00

Riskper4 0.45 0.50 0.50 1.00

Riskprop -0.22 -0.20 -0.06 -0.04 1.00

The Netherlands Riskper1 1.00

Riskper2 0.46 1.00

Riskper3 0.28 0.20 1.00

Riskper4 0.22 0.24 0.77 1.00

Riskprop -0.03 -0.04 -0.08 -0.03 1.00

Singapore Riskperl 1.00

Riskper2 0.87 1.00

Riskper3 0.39 0.37 1.00

Riskper4 0.35 0.36 0.78 1.00

Riskprop -0.22 -0.24 -0.20 -0.17 1.00

MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000 311

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

questions measuring these constructs were com- could be determined by examining the sign

puted. As evidence of discriminant reliability, (positive or negative) and statistical significance

each question should correlate more highly with of the T-value for its corresponding path. With a

other questions measuring the same construct significance level of 0.01, the acceptable T-value

than with other questions measuring other would be 2.326.

constructs (Chin 1998). The risk propensity and

risk perception constructs had discriminant Risk propensity had an inverse effect on risk

validityfor the entire dataset and for each culture perception but had no direct effect on willingness

(see Table 5). to continue a project. Decision makers with

higher risk propensity tended to have lower risk

perception. Thus, H1 was supported but H3 was

not supported. Risk perception had an inverse

StructuralModel

effect on willingness to continue a project. Deci-

sion makers with lower risk perception tended to

The use of PLS (or any variance-based approach

be more willing to continue a project in the face

to structuralequation modeling)for data analyses

of difficulties. Thus, H2 was supported. Level of

tends to bias the results toward higher estimates

sunk cost did not affect risk perception but had a

for indicatorloadings in the measurement model

direct effect on willingness to continue a project.

at the expense of lower estimates for path

The higher the level of sunk cost, the greater the

coefficients in the structural model (Chin 1998).

This tradeoff between measurement and struc- willingness of decision makers to continue a

tural models can be avoided by having a large project. Hence, H4 was not supported but H5

was supported.

sample size, at least 10 times the largest number

of independent constructs affecting a dependent

construct (Chin 1998). Since the largest number Figures 3, 4, and 5 depict the structuralmodels

for Finland, the Netherlands, and Singapore

of independent constructs affecting a dependent

construct in the theoretical model was three, the respectively. Hypotheses on culturaldifferences

(Hla and H4a) could be tested by statistically

sample size for each culture was large enough to

overcome the problem of biased results. comparing corresponding path coefficients in

these structural models. The lack of support for

H4 suggested that level of sunk cost did not

With adequate measurement models, the hypo-

affect risk perception in general (across various

theses were tested by examining the structural

models. The explanatory power of a structural cultures). Thus, there was no support for H4a.

model could be evaluated by looking at the R2 Singapore subjects had lower uncertaintyavoid-

ance than Finnish and Dutch subjects. Hence,

value (variance accounted for) in the final

Hla was tested by statistically comparing the

dependent construct. In this study, the final

path coefficient from risk propensity to risk per-

dependent construct (willingness to continue a

ception in the structuralmodel for Singapore with

project) had R2 values of 0.45 for the combined

the corresponding path coefficients in the struc-

dataset, 0.53 for Finland, 0.48 for the Nether-

tural models for Finland and the Netherlands.

lands, and 0.39 forSingapore. Since priorstudies

This statistical comparison was carried out using

could explain no more than 14% of the variance

the following procedure:15

in decision makers' willingness to continue a

project, the structural models proposed in this

study possessed greater explanatory power than

earlier models, making interpretation of path

coefficients meaningful. After computing path

estimates in the structuralmodel using the entire

sample, PLS used a jackknifing technique to '5WethankWynneChinforsuggestingthis procedure.

obtain the corresponding T-values. Each We providethe detailsof this procedurebecause it has

not been documentedelsewhere. Earlierstudies that

hypothesis (H1 to H5) corresponded to a path in comparedcorresponding pathsacrossstructural models

the structural model for the combined dataset had simply looked at the numericalvalues of path

(see Figure 2). Support for each hypothesis coefficientswithoutconductinga statisticaltest (e.g.,

Thompsonet al. 1994).

312 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

*

p < 0.01

Note: Hypotheses in bold were supported.

[_ill t?.~1~

1_ ii [~(ll ti*n [oIs[JE(e]ft~e] muon

- .ris u Ir.jtii

*

p < 0.01

Note: Hypotheses in bold were supported.

c

MI. 'TAR ;;l 'kI ; * ; ' -- ' .';

MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000 313

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

* p < 0.01

Note: Hypotheses in bold were supported.

a - 0S- S . S

*

p < 0.01

Note: Hypotheses in bold were supported.

314 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

Note: Paths in dash are unsupported, path in bold is culturallysensitive, and ovals are

Indicatorsfor constructs (see the appendix).

SE"di i S ESSilli SI 1

Spooled = v{[(Nj- 1)/(N, + N2- 2)]x SE,2 + [(N2- Discussion and

1)/(N1 + N2- 2)]x SE22}

Implications

t = (PC - PC2) / [SpooledX V(1/N1+ 1/N2)]

By integratingboth situational (level of sunk cost)

and individual factors (risk propensity and risk

where = pooled estimator for the variance

Spooled

perception) into a theoretical model, this study

t = t-statistic with N, + N2 - 2 has accounted for a substantial portion of the

degrees of freedom variance in decision makers' willingness to

Ni = sample size of dataset for culture continue a project. Moreover, it illustrates how

i cross-cultural differences (on uncertainty avoid-

SE, = standard error of path in

ance) may moderate the relationship between

structuralmodel of culture i risk propensity and risk perception, and adds a

PC, = path coefficient in structural cultural dimension to the theoretical model.

model of culture i

Figure 6 summarizes the results of this study.

Results showed that the path coefficient from risk

propensity to risk perception in the structural Discussion of Findings

model for Singapore was significantly stronger

than the corresponding path coefficients in the In a previous study using U.S. subjects, Sitkin

structuralmodels for Finland(t = 11.57, p < 0.01) and Weingart (1995) reportedthat riskpropensity

and the Netherlands (t = 27.45, p < 0.01). As affected riskbehavior of decision makers through

hypothesized, cultures lower on uncertainty their risk perception. Specifically, decision

avoidance yielded a significantlystronger inverse makers high on risk propensity tended to have

relationship between risk propensity and risk low risk perception, causing them to be more

perception than cultures higher on uncertainty willing to take risk. The results of this study

avoidance. Thus, H a was supported. support such a relationship by showing that the

MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000 315

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

effect of risk propensity on decision makers' invested substantial resources. A priorstudy by

willingness to continue a projectwas mediated by Keilet al. (1995a) found that the sunk cost effect

risk perception. The strong relationship between existed in both the U.S. and Finland. Results of

risk propensity and risk perception, reported by the study reported here show that the sunk cost

Sitkin and Weingart, also ties in with the cross- effect also exists in the Netherlands and

cultural finding of this study. Based on Hofstede Singapore.

(1991), the U.S. is higher on uncertainty

avoidance than Singapore but lower on uncer-

tainty avoidance than the Netherlands and for Future Research

Implications

Finland. Collectively, both sets of results pointto

the fact that lower uncertaintyavoidance cultures

One direction for future research would be to

(e.g., Singapore and the U.S.) may have stronger

replicate this study across a broader range of

relationships between risk propensity and risk cultures. While Singapore is on the low end of

perception than higher uncertainty avoidance Hofstede's (1991) uncertainty avoidance index,

cultures (e.g., the Netherlands and Finland).

the Netherlands and Finland are closer to the

middle. Thus, an obvious extension would be to

To furtherexplore how cross-cultural differences replicate this study in very high uncertainty

may impact decision makers' willingness to avoidance cultures (e.g., Greece, Portugal, or

continue a project, an F-test using culture as the Guatemala) (Hofstede 1991) to determine

independent variable was carried out. The result whether the results observed for the Netherlands

showed that the three cultures had significant and Finlandwould still hold. Likewise, this study

differences in terms of decision makers' willing- could be conducted in other low uncertainty

ness to continue a project (F = 15.40, p < 0.01), avoidance cultures (e.g., Jamaica, Denmark, or

confirmed by a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis Sweden) (Hofstede 1991) to see if the results

test (X2= 27.15, p < 0.01). A multiplecomparison obtained for Singapore would still apply.

procedure revealed that Singapore subjects

(mean = 66.04, std dev = 21.73) were more Another avenue for future research would be to

willing to continue with the project than Dutch extend decision making from an individual to a

(mean = 56.03, std dev = 26.25) and Finnish group level. Cohesive groups that operate with a

subjects (mean = 53.62, std dev = 25.05). Thus, "groupthink" attitude tend to be more committed

the stronger relationshipbetween risk propensity to their current courses of action (Street and

and risk perception in a low uncertainty avoid- Anthony 1997). It would be interesting to study

ance culture appears to be translated into greater how group factors (e.g., group cohesion) may

decision makers' willingness to continue a interactwith individualfactors (e.g., risk propen-

project. sity and risk perception) to affect groups' willing-

ness to continue a project. Given that groups in

The effect of the level of sunk cost on willingness some cultures may be more cohesive and prone

to continue a project (the sunk cost effect) was to groupthinkthan groups in other cultures (Tan

direct and not mediated by risk perception. This et al. 1998), it would be interesting to observe

lack of mediated impact (H4 not supported) whether multi-culturalgroups could be used to

suggests that decision makers were unlikely to reduce escalation of commitment tendencies at

have equated level of sunk cost with level of a group level. This research area is important

project completion. A likely explanation for this because groups, rather than individuals, are

result, consistent with prospect theory (Kahne- usually responsible for critical organizational

man and Tversky 1979; Tversky and Kahneman decisions. Hence, knowing the circumstances

1981), is that the level of sunk cost creates a under which groups may yield to escalation of

cognitive bias at a subconscious level, prompting commitmenttendencies could help organizations

decision makers to take risk. This subconscious to alleviate such problems.

cognitive bias may be manifested in the form of

emotional attachment that decision makers A third possible direction for future research

commonly display for projects in which they have would be to study how escalation of commitment

316 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keilet al./Culture&Escalationof Commitment

tendencies could be alleviated so as to reduce apply. For example, the results showed that there

wasteful commitmentof money to failingprojects. was an inverse relationship between risk

The results of this study suggest that risk identi- perception and willingness to continue a project.

fication techniques (Barkiet al. 1993; Ropponen However, this relationship may be moderated by

and Lyytinen2000) may help decision makers to organizational factors. Ifthe level of sunk cost is

develop more conservative assessments of the considered low by the standard of the organi-

situation by increasing their risk perception and zation and decision makers can abandon the

making them more conscious of software risk. project with no adverse consequences (e.g.,

Since projectinformationtends to be ambiguous losing his or her job), decisions to continue the

or even contradictory, a critical role of risk project would be considered risk-seeking. Thus,

identificationtechniques is to improve the quality decision makers with low risk perception may be

of feedback available to decision makers. Such more willing to continue the project. But if the

level of sunk cost is considered high by the

techniques may reduce decision makers'

standard of the organization and decision makers

willingness to continue a project (Lyytinenet al.

cannot abandon the project without any adverse

1996). Awareness of software risk may also

consequences, decisions to continue the project

prompt decision makers to develop strategies would be considered risk-averse. Therefore,

(Ropponen and Lyytinen 1997) to deal with decision makers with high risk perception may be

unavoidable risk. Such issues have not been

more willing to continue the project. Another

adequately studied but some scholars have

organizational issue is the availability of slack

initiated efforts in this direction by putting

resources. Decision makers who have the luxury

together various types of software risk with of such resources tend to demonstrate higher

appropriate risk management strategies (e.g., risk propensity. These issues can be tested in

Keil et al. 1998; Lyytinenet al. 1998; Ropponen field studies.

and Lyytinen2000).

The theoretical model proposed in this study

Fourth, it would be useful to identify additional could be refined for future research. Specifically,

situationalor individualfactors that may influence the two paths that were not supported by the

decision makers' willingness to continue a pro- results may be omitted. Other constructs that

ject. Examples of situational factors are the may contributeto decision makers' willingness to

availability of an alternative project (Keil et al. continue a project or moderate certain paths in

1995a) and foreseeability of the negative the model may be added. Figure 7 consolidates

feedback (Conlon and Wolf 1980). Examples of all of the research ideas discussed above into a

individual factors are the responsibility level theoretical model to guide future research efforts

(Staw et al. 1997) and the education and (the bold lines are culturally-sensitive paths).

experience of the decision maker (Ropponen and While this study focuses on cultural factors

Lyytinen2000). Empiricalstudies have reported affecting decision makers, future studies could

that decision makers were more willing to also examine organizational culture.

continue a projectwhen there were no alternative

projects, when the negative feedback was

foreseeable, when they were responsible for

initiatingthe project, and when they were lacking Implications for Practice

in education and experience withsimilarprojects.

However, it is plausible that these factors The strength of the escalation of commitment

affected decision makers by altering their risk behavior appears to vary from one culture to

perception. Future versions of this study could another. While prior work has tentatively attri-

incorporate these factors into the theoretical buted such variations to culturalfactors (Chow et

model to see whether it could account for even al. 1997; Keil et al. 1995a; Sharp and Salter

more of the variance in decision makers' 1997), this study is the first to incorporate a

willingness to continue a project. manipulation check to show that uncertainty

avoidance (a culturalfactor) affects escalation of

Finally, this study can be replicated in organi- commitment behavior. This finding is useful for

zational settings to see if the findings would still managers undertaking global software projects.

MISQuarterlyVol.24 No. 2/June2000 317

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

Note: Paths in bold may be culturallysensitive.

S .0. . 06'

6rkmgoTi uj4z;l-

In particular,managers need to take into account tion of such projects usually depends on over-

such culturaldifferences when outsourcing soft- coming (rather than avoiding) risk, appointing

ware projects to development teams from dif- managers with high risk propensity reduces the

ferent cultures. Teams from low uncertainty likelihood of such projects being terminated

avoidance cultures may be more risk-seeking prematurely.Conversely, managers with low risk

and more susceptible to escalation of commit- propensity (common in high uncertainty avoid-

ment behavior than teams from high uncertainty ance cultures) can be assigned to software

avoidance cultures. Ifmanagers want to alleviate projects that use familiartechnologies or deve-

such differences in behavior among all the deve- lopment methods. Since such projects can be

lopment teams, they need to establish common completed with minimal risk, having managers

policies to guide teams on when to continue with low risk propensity reduces the possibility

working on projects with questionable prospects that such projects would be allowed to continue

for success. when prospects for success are questionable.

Matching managers to projects can enhance the

Risk propensity appears to influence decision probability of project success (Lyytinen et al.

makers' willingness to continue a project through 1998).

risk perception. This result, consistent with Sitkin

and Weingart (1995), has two practically useful Second, it may be possible to modify managerial

implications. First, it may be possible to match behavior by manipulating risk perception. For

managerial characteristics to project nature. managers with very high risk propensity, which

Managers with high risk propensity (common in can translate into very low risk perception

low uncertainty avoidance cultures) can be (especially in low uncertaintyavoidance cultures),

assigned to software projects involvingadvanced measures can be employed to alter their risk

or new technologies. Since successful comple- perception. These include promoting open

318 MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keil et al./Culture & Escalation of Commitment

discussion to get perceptions of people outside took a necessarily narrowfocus so as to achieve

the projectteam (Lyytinenet al. 1998), reminding a high degree of control over extraneous

them about the availabilityof alternative projects variables. There are organizational and political

(Keil et al. 1995a), advising them to focus on the factors that may also influence decision makers'

decision process rather than outcomes (Simon- willingness to continue a project. These factors

son and Staw 1992), and assuring them that the have not been investigated here and may not

decision outcomes do not reflecttheir managerial lend themselves to experiments.

abilities (Simonson and Staw 1992). These mea-

sures can help managers to form a more realistic Third,the scenario used in this study represented

risk perception and possibly avoid delaying deci- an over-simplification of options available to

sions to discontinue or redirecttroubled projects. managers who face the decision of how to handle

a projectwith uncertain prospects for success. In

A finding that is consistent across cultures is that this study, the decision was framed as a choice

decision makers tend to be more willing to of whether or not to continue the project. Clearly,

continue a project when the level of sunk cost is managers can make other choices such as

high. Thus, when the level of sunk cost is very redirecting the project by replacing key indivi-

high, some "de-escalation" tactics (Keil and duals involved or changing the requirement

Robey 1999) can be used to help managers specifications of the project (Keil and Robey

avoid escalation of commitment behavior or at 1999). Fourth, this study used a single-item

least minimize its impact when it does occur. measure for the risk propensity construct.

Promising tactics include making costs of con- Although such a measure does not render the

tinuing a project salient to decision makers results of structural equation modeling analysis

(Brockner et al. 1979), encouraging decision invalid (Hair et al. 1998), it does weaken the

makers to set absolute spending limits(Brockner measurement models and can pose theoretical

et al. 1979), asking decision makers to set target difficulties.The similarfinding on risk propensity,

levels of completion at specific time intervals reported by Sitkinand Weingart (1995), provides

(Simonson and Staw 1992), and advising deci- support for the findings of this study. Never-

sion makers to disregard level of sunk cost when theless, findings pertainingto the risk propensity

deciding whether or not to continue a project construct should be validated in future studies

(Howe and McCabe 1983). Another tactic is to using multiple-itemmeasures for this construct.

reduce project size by breaking large projects

into smaller chunks, so that total sunk cost is

minimized, while the relative sunk cost on a

specific deliverable rises quickly, thus pushing Conclusion

people to complete various segments of the

This study makes some novel contributions to

project (Keil and Robey 1999). Together, these

tactics are organizational safeguards against the software project management knowledge. First,

sunk cost effect. it advances a theoretical model to explain

decision makers' willingness to continue a soft-

ware project.By incorporatingconcepts from risk-

taking theory, in addition to the commonly-tested

Limitations of This Study level of sunk cost, this theoretical model has

greater explanatory power than earlier models.

As is the case with all laboratoryexperiments, we Second, it illustrates how uncertainty avoidance

need to be cautious when generalizing the results (a cultural factor) can impact decision makers'

of this study for several reasons. First, results willingness to continue a software project. While

obtained using student subjects may be some- earlier studies have speculated on the impor-

what different from results obtained using actual tance of culturalfactors, this study pinpoints the

managers, who have been victims of the moderating impact of a culturalfactor withthe aid

escalation of commitment phenomenon and who of a theoretical model. In doing so, it adds a

may be more sensitive to such a phenomenon. cultural dimension to existing knowledge on the

Second, the experiments conducted in this study escalation of commitment phenomenon.

MIS QuarterlyVol. 24 No. 2/June 2000 319

This content downloaded from 172.12.137.157 on Thu, 11 Sep 2014 17:23:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Keilet al./Culture&Escalationof Commitment

As organizations become more computerized, Brockhaus, R. H. "Risk Taking Propensity of

software projects will consume an ever Entrepreneurs," Academy of Management

increasing amount of organizational resources. Journal (23:3), 1980, pp. 509-520.

Useful theories on escalation of commitment Brockner, J. "The Escalation of Commitment to

behavior can potentially lead us to "de- a Failing Course of Action: TowardTheoretical

escalation" tactics (Keil and Robey 1999) that Progress," Academy of Management Review

may help organizations to save millionsof dollars (17:1), 1992, pp. 39-61.

in unnecessary expenses. And as multicultural Brockner, J., Shaw, M. C., and Rubin, J. Z.

teams are increasingly being deployed for large "Factors Affecting Withdrawal From an Esca-

software projects, these theories need to be lating Conflict: Quitting Before It's Too Late,"

evaluated for cross-cultural applicability. This Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

study is an initialattempt to develop a theory on (15:5), 1979, pp. 492-503.

escalation of commitment behaviorwitha cultural Brooks, F. P. The MythicalMan-Month: Essays

dimension. on Software Engineering, Addison-Wesley,

Reading, MA 1975.

Charette, R. N. Software Engineering Risk

Analysis and Management, McGraw Hill,New

Acknowledgements

York, 1989.

We thank the senior editor, the associate editor, Chin, W. W. PLS-Graph Manual Version 2.7,

three anonymous reviewers, and Wynne Chin for University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, 1994.

their many constructive and insightfulcomments Chin, W. W. "The Partial Least Squares

on this paper. Approach to StructuralEquation Modeling,"in

Modern Methods for Business Research, G. A.

Marcoulides (ed.), Lawrence Erlbaum Asso-

ciates, Mahwah, NJ, 1998, pp. 295-336.

References Chow, C. W., Harrison,P., Lindquist,T., and Wu,

A. "Escalating Commitment to Unprofitable

Abdel-Hamid, T., and Madnick, S. E. Software Projects: Replication and Cross-Cultural

Project Dynamics: An Integrated Approach, Extension,"ManagementAccountingResearch

Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1991. (8:3), 1997, pp. 347-361.