Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Fall of Baghdad: Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PHD

Uploaded by

scribd2Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Fall of Baghdad: Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PHD

Uploaded by

scribd2Copyright:

Available Formats

The Fall of Baghdad

Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PhD

Genghiz Khan died in 1227. Upon his death, his vast empire

was divided up into five parts: (1) Mongolistan consisting of

the Mongol home turf, (2) Chagtai, consisting of Khorasan

and Farghana Valley, (3) Persia, ruled by the Il-Khans, (4)

Russia and Kazakhstan, ruled by the Golden Hordes and (5)

China. The Mongols continued their advance after Genghiz.

In 1229, they planned three great expeditions. The first was

to complete the conquest of southern China. This effort was

not completed until 1276 during the reign of Kublai Khan.

The second expedition was to complete the conquest of

southern Russia, Poland, Hungary and Bulgaria. The Mongols

were successful in this campaign and ruled these territories

for over two hundred years. The third expedition under

General Charmagun was against Prince Jalaluddin of

Khorasan.

After crossing the Indus at the Battle of Attock in 1221,

Jalaluddin sought refuge with Altumish, the able Mamluke

Sultan of Delhi. But Altumish knew the risks associated with

giving refuge to a foe of Genghiz. Although he was treated

with the dignity befitting a prince, Jalaluddin knew that his

welcome mat in Delhi was very thin. In 1223, he returned to

Isfahan via Sindh and Makran, suffering the ravages of that

inhospitable desert, much as Alexander had done fifteen

centuries earlier. Soon, with the help of his brother,

Jalaluddin was in possession of what was left of Khorasan,

Mazanderan and Iraq. In 1225, he marched against the

Caliph Al Nasir to seek revenge against an enemy of his

father. The armies of the Caliph were routed and Baghdad

was besieged. Jalaluddin continued his march into Georgia

and occupied Tiflis in 1226. This infuriated the Georgians

who made an alliance with the Mongols and the Russian

Kipchaks against Jalaluddin.

Jalaluddin now had to face the combined armies of the

Georgians, the Russian Kipchaks and the Mongols. At the

Battle of Isfahan in 1227, he defeated the Mongols. His

strategy in war was to face the Mongols in the open field and

to avoid the pitfalls of his father who had tried to hole

himself up in one fort after another. This gave him the

advantage of mobility and rapid enveloping movements,

tactics that the Central Asian horsemen were masters of. In

1229, he made peace with the new Caliph Al Muntasir (1226-

1242). But now his good fortune ran out. The Mongol armies

of Charmagun caught him unprepared on the Moghan plains

(1230) and Jalaluddin narrowly escaped with his life. Shortly

thereafter a Kurdish robber assassinated him.

Thus perished the bravest of Muslim soldiers who was the

only one amongst the kings and princes of his era, Muslim or

Christian, to face the Mongol hordes in open combat and

defeat them on several occasions. Brilliant as he was in war,

Jalaluddin suffered from a lack of organizational skills

required of a statesman. He was always restless, moving

from battle to battle. It would have taken a combination of

his prowess with the wisdom of a Nizam ul Mulk (d. 1091) to

contain the fierce Mongols.

In the meantime, the devastation of Khwarazm continued.

The Mongols revisited the cities and provinces they had

already destroyed and what was left after the invasions of

Genghiz Khan was devastated once again. In 1251, Mangu

was elected the Chief Khan of all Mongols. His first act was to

launch two expeditions, one under his brother Kublai Khan to

conquer southern China and the other under Hulagu Khan to

bring an end to the Caliphate in Baghdad. On both counts,

the Mongols were successful.

Hulagu established himself in Isfahan and methodically

moved to eliminate all resistance. His first objective was the

Assassins who posed a potential threat to his rear guard.

Hulagu knew that the Assassins, an offshoot of the Fatimid

sect, were a major factor in the instability of the Muslim

world during the 11th and 12th centuries and had terrorized

successive Muslim dynasties by assassinating generals,

viziers and sultans alike. It was the dagger of an assassin

that had brought to an end the life of the brilliant vizier,

Nizam ul Mulk (1091). During the year 1256, Hulagu

attacked the hideouts of the Assassins, eliminating them one

after the other.

In the winter of 1257, Hulagu moved towards Baghdad. A

de-facto alliance was formed between the Christian powers

and the Mongols to eliminate Islam. The Crusaders and the

Armenians attacked in northern Syria diverting some of the

Turkish contingents that might have been available for the

defense of Baghdad. Al Musta’sim was no military match for

Hulagu. Suffering from the same kind of fatalistic self-

delusion that had characterized the encounter of Shah

Muhammed of Khwarazm with Genghiz Khan, Al Musta’sim

failed to organize an effective defense of the capital. The

treasury of the Caliph that could have been used to raise a

large army remained closed. Hulagu sent a summons to

Caliph Musta’sim to surrender. When the Caliph refused,

Hulagu laid siege to the Abbasid capital and methodically

moved to reduce it.

In June 1258, the city of Baghdad surrendered. No

description can do justice to the horrors that followed. The

sack of Baghdad lasted a week. More than a million

inhabitants were slaughtered. Al Musta’sim was wrapped in a

carpet, beaten with clubs and tramped to death by Mongol

horses. Mosques were pulled down. Libraries burned. Great

men of learning were tortured to death. Artisans were

enslaved. Women were dragged, abused and left to die along

far-away roads. The dams on the Tigris and the Euphrates

that the Abbasids had built up over a period of five centuries

were demolished. The destruction of dams throughout

Central Asia depressed agriculture and slowed population and

economic recovery for many centuries. Baghdad, which was

once the premier city of the world, became a ghost town.

The fall of Baghdad marked a major event in world history.

With it, the curtain fell on the classic Islamic period. Baghdad

had been founded and established by the Abbasids as the

capital of orthodox Islam after Madina and Damascus. It was

the seat of the Caliphate and the vortex of Islamic political

life. It was to Baghdad that kings and sultans alike turned,

seeking legitimacy for their temporal power and guidance on

spiritual matters. With the demolition of the Caliphate in

Baghdad, Muslims had to reinvent that institution so that the

temporal and spiritual life of Islam might continue to have a

focus.

Hulagu established himself in Hamadan from where he

organized more expeditions. All of Iraq was subjugated.

Aleppo in northern Syria fell in 1260 to the combined

onslaught of Mongol, Armenian and Crusader armies.

Palestine lay ahead and held the key to Egypt and the cities

of Mecca and Madina. Only the Ganges plains of India

escaped the Mongol conquests thanks to the resistance of

the Mamluke sultans of India and the statesmanship of

Altumish and his daughter Razia Sultana. The hour was dark

indeed. It appeared that the light of Islam that had been lit

six hundred years earlier might be physically extinguished.

The classic Islamic civilization was the light that had kept

learning, art and culture alive for 600 years while Europe lay

in the stupor of its Dark Ages. This civilization, even in its

waning years, was at once spiritual and empirical, absorbing

and transforming the best that the ancient civilizations of

Greece, India, Persia and Egypt had to offer. After the fall of

Baghdad, Islam went through a process of self-renewal. It

turned increasingly inward, towards tasawwuf and the

sciences of the soul. It was this Sufic Islam that was to

conquer the conquering Mongols, win the hearts of millions in

India, Indonesia and Africa and shape the destiny of three

continents for the next 400 years.

Thus it was in the year 1258 that a civilization died even as it

renewed and expressed itself on a different plane.

You might also like

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Religion and the Role of Islam in the Mongol EmpireFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Religion and the Role of Islam in the Mongol EmpireNo ratings yet

- The Knights of Islam: The Wars of the Mamluks, 1250 - 1517From EverandThe Knights of Islam: The Wars of the Mamluks, 1250 - 1517Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Hulagu KhanDocument8 pagesHulagu Khanའཇིགས་བྲལ་ བསམ་གཏན་No ratings yet

- BTL of Ayan JulutDocument12 pagesBTL of Ayan Julutmisba100% (2)

- World HistoryDocument6 pagesWorld Historymusa naseerNo ratings yet

- Siege of Baghdad (1258)Document5 pagesSiege of Baghdad (1258)Syed Mohsin Mehdi TaqviNo ratings yet

- Hulegu and The Fall of BaghdadDocument18 pagesHulegu and The Fall of BaghdadAndrew Greenfield Lockhart100% (1)

- Hulagu KhanDocument10 pagesHulagu KhanAdnan Ahmed VaraichNo ratings yet

- The Last Great Nomadic Challenges: From Chinggis Khan To TimurDocument10 pagesThe Last Great Nomadic Challenges: From Chinggis Khan To TimurJose Luis Pino MatosNo ratings yet

- 5 .Expansion in The South KHILJIDocument10 pages5 .Expansion in The South KHILJIsehar mustafaNo ratings yet

- Hulagu Khan - WikipediaDocument50 pagesHulagu Khan - WikipediaAB BaliNo ratings yet

- Mongol Transition to IslamDocument42 pagesMongol Transition to IslamSarbash BalochNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Growth of Muslim Society in The Sub-ContinentDocument2 pagesEvolution and Growth of Muslim Society in The Sub-ContinentSaleemAhmadMalikNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Growth of Muslim Society IDocument3 pagesEvolution and Growth of Muslim Society IMehreen AbbasiNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Growth of Muslim Society in The Sub-ContinentDocument3 pagesEvolution and Growth of Muslim Society in The Sub-ContinentShahab Uddin ShahNo ratings yet

- Unit 1-Topic 1-Advent of Islam in South AsiaDocument5 pagesUnit 1-Topic 1-Advent of Islam in South AsiaS Alam100% (4)

- Genghis Khan's Death and The Continuation of The EmpireDocument2 pagesGenghis Khan's Death and The Continuation of The EmpirePooja GuptaNo ratings yet

- Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Sultanate Period NotesDocument38 pagesTnpsc Group 1 & 2 Sultanate Period NotesNivetha SNo ratings yet

- Rise and Fall of the Mamluk Sultanate in EgyptDocument11 pagesRise and Fall of the Mamluk Sultanate in EgyptIntan SyahidahNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Growth of Muslim Society in SubcontnentDocument8 pagesEvolution and Growth of Muslim Society in Subcontnentanon_203046281No ratings yet

- The Heritage of Ghazni and BukharaDocument12 pagesThe Heritage of Ghazni and Bukharasehar mustafaNo ratings yet

- Mohammad Bin Qasim Raja Dahir: Early Muslim InvasionsDocument15 pagesMohammad Bin Qasim Raja Dahir: Early Muslim Invasionsshy_88No ratings yet

- Evolution of Muslim Society in Sub-ContinentDocument70 pagesEvolution of Muslim Society in Sub-Continentfatima vohraNo ratings yet

- Foundation and Consolidation of The SultanateDocument10 pagesFoundation and Consolidation of The SultanateYinwang KonyakNo ratings yet

- The Muslims Came To The Indian Subcontinent in Waves of ConquestDocument2 pagesThe Muslims Came To The Indian Subcontinent in Waves of ConquestMehreen AbbasiNo ratings yet

- Mongol Bangsa Mendirikan Dinasti Ilkhan Berbasis IslamDocument13 pagesMongol Bangsa Mendirikan Dinasti Ilkhan Berbasis IslamVelLa Lilinsa AsbanuNo ratings yet

- The KhiljiDocument2 pagesThe KhiljiKiranNo ratings yet

- Hisotry of South Asia Abdul RazzaqDocument12 pagesHisotry of South Asia Abdul RazzaqShazeb KhanNo ratings yet

- Khiljis and TughlaqsDocument8 pagesKhiljis and Tughlaqskonyakpangshing904No ratings yet

- Iran Under Mongol Domination: The Effectiveness and Failings of A Dual Administrative SystemDocument15 pagesIran Under Mongol Domination: The Effectiveness and Failings of A Dual Administrative SystemTya KusumahNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of the Delhi Sultanate Dynasties (1206-1526)/TITLEDocument7 pagesThe Rise and Fall of the Delhi Sultanate Dynasties (1206-1526)/TITLEabhiroopboseNo ratings yet

- The Age of Pax MongolicaDocument38 pagesThe Age of Pax Mongolicamirzatech100% (1)

- Idc AssignmentDocument10 pagesIdc AssignmentAnila NawazNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Muslim Rule Over Sub-Continent: Umayyad DynastyDocument8 pagesEvolution of Muslim Rule Over Sub-Continent: Umayyad Dynastyimarnullah jatoiNo ratings yet

- Problem of MongolDocument2 pagesProblem of MongolRita UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- 75816-Venegoni - Hulagu's Campaign in The West (1256-1260) A011Document11 pages75816-Venegoni - Hulagu's Campaign in The West (1256-1260) A011Rodrigo Méndez LópezNo ratings yet

- History Short NoteDocument5 pagesHistory Short NoteAbdul Rehman AfzalNo ratings yet

- Late Baghdad Abbasids and Fatimid CaliphatesDocument7 pagesLate Baghdad Abbasids and Fatimid CaliphatessidraNo ratings yet

- DelhiDocument5 pagesDelhiTheebiha JeysankarNo ratings yet

- The Conquest of Sindh: Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PHDDocument6 pagesThe Conquest of Sindh: Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PHDMubashir MalikNo ratings yet

- Ala-ud-Din Khilji: Military Conquests of a Powerful Delhi SultanDocument10 pagesAla-ud-Din Khilji: Military Conquests of a Powerful Delhi SultanRamkrishna Choudhury100% (1)

- CC5 Mod 2DDocument7 pagesCC5 Mod 2Dravinderpalsingh04184No ratings yet

- The Mongols: Chinghis Khan and The Rise of The MongolsDocument3 pagesThe Mongols: Chinghis Khan and The Rise of The MongolspaulprovenceNo ratings yet

- The Slave Dynasty 1Document7 pagesThe Slave Dynasty 1advocacyindyaNo ratings yet

- Buqa ChingsangDocument14 pagesBuqa ChingsangGrigol JokhadzeNo ratings yet

- CH 5 Nomadic Empire 1Document35 pagesCH 5 Nomadic Empire 1NooneNo ratings yet

- Origins and Rise of the Golden HordeDocument2 pagesOrigins and Rise of the Golden HordeAnonymous 7isTmailHuseNo ratings yet

- Muslim Influence in The Sub-ContinentDocument9 pagesMuslim Influence in The Sub-ContinentZaufishan HashmiNo ratings yet

- Mongol Invasions of GeorgiaDocument4 pagesMongol Invasions of GeorgiaGhandandorphNo ratings yet

- CSE Medieval History PYQs (As)Document145 pagesCSE Medieval History PYQs (As)BIODIVERSITY atRISKNo ratings yet

- II. The Heritage of Ghazni and BukharaDocument10 pagesII. The Heritage of Ghazni and Bukharamuhammad waqasNo ratings yet

- The Men Who Stopped The Mongols: September 2007Document14 pagesThe Men Who Stopped The Mongols: September 2007af asdwdNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 NotesDocument7 pagesChapter 13 NotesIvanTh3Great85% (13)

- Nomadic Empires Class 11 Notes HistoryDocument6 pagesNomadic Empires Class 11 Notes HistoryDhanya Sunil PNo ratings yet

- Nomadic Empires Class 11 Notes HistoryDocument6 pagesNomadic Empires Class 11 Notes HistoryFIROZNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document7 pagesChapter 5Brahma Dutta DwivediNo ratings yet

- The Muslim Period in Indian HistoryDocument15 pagesThe Muslim Period in Indian HistoryMuhammed Irshad KNo ratings yet

- SaladinDocument1 pageSaladinKapco ChallengersNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument35 pagesDocumentruchirveeNo ratings yet

- Genghis Khan & the Mongol Conquests 1190–1400From EverandGenghis Khan & the Mongol Conquests 1190–1400Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Portfolio Diversification: Presented By:-Mudassar Husain Roll No. 19mbak23 Asim Abid Roll No. 19mbak61Document18 pagesPortfolio Diversification: Presented By:-Mudassar Husain Roll No. 19mbak23 Asim Abid Roll No. 19mbak61scribd2No ratings yet

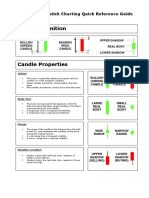

- Candle Properties PDFDocument1 pageCandle Properties PDFscribd2No ratings yet

- Candle Properties PDFDocument1 pageCandle Properties PDFscribd2No ratings yet

- Who Recommended Hand-Rub FormulationDocument9 pagesWho Recommended Hand-Rub FormulationSaeed Mohammed100% (2)

- Candle PatternDocument3 pagesCandle Patternscribd2No ratings yet

- Affiliate MarketingDocument11 pagesAffiliate Marketingscribd2No ratings yet

- 150th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma GandhijiDocument1 page150th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhijiscribd2No ratings yet

- Forex Card RatesDocument2 pagesForex Card RatesKrishnan JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Candle Patterns Quick GuidesDocument20 pagesCandle Patterns Quick Guidesscribd2No ratings yet

- EntreprenuerDocument3 pagesEntreprenuerscribd2No ratings yet

- Business Model To Start Aloevera ProductsDocument9 pagesBusiness Model To Start Aloevera Productsscribd2No ratings yet

- FM 406 PDFDocument257 pagesFM 406 PDFWotanngare NawaNo ratings yet

- The Fall of Baghdad: Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PHDDocument4 pagesThe Fall of Baghdad: Contributed by Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PHDscribd2No ratings yet

- Investmentavenues 150413012353 Conversion Gate01 PDFDocument24 pagesInvestmentavenues 150413012353 Conversion Gate01 PDFPrashant JacobNo ratings yet

- Christ Be Our Light Easter Text Octavo PDFDocument9 pagesChrist Be Our Light Easter Text Octavo PDFalremNo ratings yet

- Harun al Rashid and Mamun- the Golden Age of ReasonDocument5 pagesHarun al Rashid and Mamun- the Golden Age of Reasonscribd2No ratings yet

- CSE - 3AF, 3BF, 3AM, 3CM MID-TERM Question Spring-2020 PDFDocument2 pagesCSE - 3AF, 3BF, 3AM, 3CM MID-TERM Question Spring-2020 PDFscribd2No ratings yet

- FM-compound TablesDocument8 pagesFM-compound Tablesscribd2No ratings yet

- Online Complaint Management SystemDocument44 pagesOnline Complaint Management SystemSona SenNo ratings yet

- Online Complaint Management SystemDocument44 pagesOnline Complaint Management SystemSona SenNo ratings yet

- Harun al Rashid and Mamun- the Golden Age of ReasonDocument5 pagesHarun al Rashid and Mamun- the Golden Age of Reasonscribd2No ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of Online Student Complaint Management SystemDocument14 pagesDesign and Implementation of Online Student Complaint Management SystemChaithra k67% (3)

- Online Complaint Management SystemDocument44 pagesOnline Complaint Management SystemSona SenNo ratings yet

- Project ReportDocument67 pagesProject ReportNeeraj MoghaNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Assignment Name: Course Name Course Code: CSE-4710Document4 pagesAssignment: Assignment Name: Course Name Course Code: CSE-4710scribd2No ratings yet

- Mid Term: Course Name Course Code: Contact Number: EmailDocument1 pageMid Term: Course Name Course Code: Contact Number: Emailscribd2No ratings yet

- Project ReportDocument67 pagesProject ReportNeeraj MoghaNo ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of Online Student Complaint Management SystemDocument14 pagesDesign and Implementation of Online Student Complaint Management SystemChaithra k67% (3)

- Design and Implementation of Online Student Complaint Management SystemDocument14 pagesDesign and Implementation of Online Student Complaint Management SystemChaithra k67% (3)

- The Definition and Unit of Ionic StrengthDocument2 pagesThe Definition and Unit of Ionic StrengthDiego ZapataNo ratings yet

- OOD ch11Document31 pagesOOD ch11Pumapana GamingNo ratings yet

- Diagrama RSAG7.820.7977Document14 pagesDiagrama RSAG7.820.7977Manuel Medina100% (4)

- Charles Henry Brendt (1862-1929)Document2 pagesCharles Henry Brendt (1862-1929)Everything newNo ratings yet

- DepEd Memorandum on SHS Curriculum MappingDocument8 pagesDepEd Memorandum on SHS Curriculum MappingMichevelli RiveraNo ratings yet

- Ky203817 PSRPT 2022-05-17 14.39.33Document8 pagesKy203817 PSRPT 2022-05-17 14.39.33Thuy AnhNo ratings yet

- Policy Based Routing On Fortigate FirewallDocument2 pagesPolicy Based Routing On Fortigate FirewalldanNo ratings yet

- What Is The Time Value of MoneyDocument6 pagesWhat Is The Time Value of MoneySadia JuiNo ratings yet

- Lead and Manage Team Effectiveness for BSBWOR502Document38 pagesLead and Manage Team Effectiveness for BSBWOR502roopaNo ratings yet

- l3 Immunization & Cold ChainDocument53 pagesl3 Immunization & Cold ChainNur AinaaNo ratings yet

- New Monasticism: An Interspiritual Manifesto For Contemplative Life in The 21st CenturyDocument32 pagesNew Monasticism: An Interspiritual Manifesto For Contemplative Life in The 21st CenturyWorking With Oneness100% (8)

- Si Eft Mandate FormDocument1 pageSi Eft Mandate FormdSolarianNo ratings yet

- Sivas Doon LecturesDocument284 pagesSivas Doon LectureskartikscribdNo ratings yet

- Surio vs. ReyesDocument3 pagesSurio vs. ReyesAdrian FranzingisNo ratings yet

- Window On The Wetlands BrochureDocument2 pagesWindow On The Wetlands BrochureliquidityNo ratings yet

- What Is ReligionDocument15 pagesWhat Is ReligionMary Glou Melo PadilloNo ratings yet

- Redox ChemistryDocument25 pagesRedox ChemistrySantosh G PattanadNo ratings yet

- Landman Training ManualDocument34 pagesLandman Training Manualflashanon100% (2)

- School RulesDocument2 pagesSchool RulesAI HUEYNo ratings yet

- On Healing Powers: Asclepius, Caduceus and AntibodiesDocument4 pagesOn Healing Powers: Asclepius, Caduceus and AntibodiesasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Foreign AidDocument4 pagesForeign AidJesse JhangraNo ratings yet

- VALUE BASED QUESTIONS FROM MATHEMATICS GRADE 10Document6 pagesVALUE BASED QUESTIONS FROM MATHEMATICS GRADE 10allyvluvyNo ratings yet

- 6 - 2010 Chapter 5 - Contrasting Cultural ValuesDocument39 pages6 - 2010 Chapter 5 - Contrasting Cultural ValuesHari KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Beaba Babycook Recipe BookDocument10 pagesBeaba Babycook Recipe BookFlorina Ciorba50% (2)

- A. Pawnshops 4. B. Pawner 5. C. Pawnee D. Pawn 6. E. Pawn Ticket 7. F. Property G. Stock H. Bulky Pawns 8. I. Service Charge 9. 10Document18 pagesA. Pawnshops 4. B. Pawner 5. C. Pawnee D. Pawn 6. E. Pawn Ticket 7. F. Property G. Stock H. Bulky Pawns 8. I. Service Charge 9. 10Darwin SolanoyNo ratings yet

- Talent Level 3 Grammar Tests Unit 2Document2 pagesTalent Level 3 Grammar Tests Unit 2ana maria csalinasNo ratings yet

- Molar Mass, Moles, Percent Composition ActivityDocument2 pagesMolar Mass, Moles, Percent Composition ActivityANGELYN SANTOSNo ratings yet

- Report On Foundations For Dynamic Equipment: Reported by ACI Committee 351Document14 pagesReport On Foundations For Dynamic Equipment: Reported by ACI Committee 351Erick Quan LunaNo ratings yet

- 2013 KTM 350 EXC Shop-Repair ManualDocument310 pages2013 KTM 350 EXC Shop-Repair ManualTre100% (7)

- Sesame Seed: T. Y. Tunde-Akintunde, M. O. Oke and B. O. AkintundeDocument20 pagesSesame Seed: T. Y. Tunde-Akintunde, M. O. Oke and B. O. Akintundemarvellous ogbonnaNo ratings yet