Professional Documents

Culture Documents

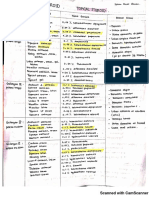

Search Uptodate: Grade 1C

Uploaded by

Gabriella TjondroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Search Uptodate: Grade 1C

Uploaded by

Gabriella TjondroCopyright:

Available Formats

! !

" Search UpToDate

View Outline % Bookmark Tools

Angle-closure glaucoma

Author: Jennifer S Weizer, MD

Section Editor: Deborah S Jacobs, MD

Deputy Editor: Jane Givens, MD

Contributor Disclosures

All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is complete.

Literature review current through: Oct 2020. | This topic last updated: Apr 17, 2020.

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases traditionally characterized by increased intraocular pressure

(IOP). However, glaucoma is more accurately defined as an optic neuropathy and may not always

be associated with increased IOP. Angle-closure glaucoma is characterized by narrowing or

closure of the anterior chamber angle.

This topic will discuss types of angle-closure glaucoma, diagnosis, and treatment. A discussion of

open-angle glaucoma is presented separately. (See "Open-angle glaucoma: Epidemiology, clinical

presentation, and diagnosis".)

DEFINITION AND TYPES

Glaucoma is defined as an optic neuropathy involving a characteristic atrophy of the optic nerve

head, often accompanied with typical visual field defects [1]. Examination of a glaucomatous

optic nerve reveals "cupping," which looks like a "hollowing out" of the optic nerve head (

picture 1). Glaucoma is often, though not always, associated with increased intraocular

pressure (IOP).

Angle-closure glaucoma is a form of glaucoma characterized by narrowing or closure of the

anterior chamber angle [2]. The normal anterior chamber angle provides drainage for the

aqueous humor, the fluid that fills the eyeball. When this drainage pathway is narrowed or

closed, inadequate drainage of the aqueous humor leads to increased IOP and damage to the

optic nerve ( figure 1A-B). Normal IOP is 8 to 21 mmHg. In acute episodes of closed-angle

glaucoma, pressures are often 30 mmHg or higher [3].

Angle-closure glaucoma is divided into two main groups:

● Primary angle-closure – Patients are anatomically predisposed to this type of glaucoma;

there is no other identifiable cause.

● Secondary angle-closure – A primary process is responsible for narrowing or closure of the

anterior chamber angle, which is secondary to that process. Examples of primary causes are

a fibrovascular membrane that grows over the angle to pull it closed, as in neovascular

glaucoma, or a mass or hemorrhage in the posterior segment of the eyeball that pushes the

angle closed [4].

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

After cataracts, glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in the world [5]. Angle-closure

glaucoma is more prevalent in populations of Asian descent, whereas open-angle glaucoma is

more common in populations of European or African descent [6]. In 2016, there were an

estimated 20 million people with angle-closure glaucoma worldwide, with 75 percent in Asia

[6,7]. This is projected to increase to 34 million worldwide in 2040 [7].

Risk factors that predispose to primary angle-closure glaucoma include [4,8-10]:

● Family history of angle-closure glaucoma

● Age >60 years

● Female

● Hyperopia (farsightedness)

● Certain medications ( table 1)

● Pseudoexfoliation (a condition in which abnormal flaky deposits on eye surfaces can weaken

the zonules that support the lens and cause it to shift forward)

● Race

The highest rates of angle-closure glaucoma are reported in Inuit and Asian populations [11-15],

and lower rates are reported in populations of African and European origin [2,13,16,17].

PATHOGENESIS

Primary angle-closure — Aqueous humor is produced by the ciliary body, flows through the

pupil, reaches the anterior chamber angle, and exits the eye. The balance between fluid

production and drainage determines the intraocular pressure.

In primary angle-closure, the lens is located too far forward anatomically and rests against the

iris. This results in pupillary block, a condition in which aqueous humor can no longer flow

normally through the pupil. Pressure builds up behind the iris, relative to the anterior chamber,

causing the peripheral iris to bow forward and cover all or part of the anterior chamber angle.

Prolonged or repeated contact between the iris and the angle can lead to scarring and functional

damage to the trabecular meshwork, the tissue in the angle that acts as a sieve through which

the aqueous humor drains ( figure 1A-B). Once the optic nerve shows damage from the high

intraocular pressure (IOP), the disease is called primary angle-closure glaucoma.

If the entire angle is blocked suddenly, as occurs in complete pupillary block, the IOP rises

rapidly, and acute symptoms can occur. These attacks of acute angle-closure glaucoma may

resolve spontaneously and recur repeatedly if not treated. Without treatment, vision loss and

even blindness can occur quickly during the attack (over hours to days), so acute angle-closure

glaucoma is a true ophthalmic emergency.

Patients with anatomically narrow angles are at risk for future angle-closure [2]. The width of

their anterior chamber angles is smaller than in normal eyes, and their peripheral iris is closer to

their anterior chamber angle than normal.

Chronic angle-closure — Chronic angle-closure results if only a portion of the angle is

blocked at a time and develops scarring. Over time, the angle may become progressively more

closed. In this variation of the disease, the IOP may be normal or only slightly elevated, in which

case symptoms will likely not occur. Patients with chronic angle-closure glaucoma may have

more damage to the optic nerve and peripheral vision when the diagnosis is established,

compared with patients with acute angle-closure glaucoma because of the absence of symptoms

and thus delayed diagnosis.

Secondary angle-closure — Secondary angle-closure results when the anterior chamber angle

becomes occluded as the result of conditions that push the iris or ciliary body forward ("pushing"

conditions) or deform the iris so that it is retracted into the angle ("pulling" conditions).

Pushing conditions include:

● Fibrosis of the pupil to the anterior surface of the lens.

● Choroidal swelling or hemorrhage (due to types of ophthalmic surgery, retinal laser

treatment, posterior scleritis, or drug reactions). Topiramate is the most common of the

sulfa-based medications to cause this rare, idiosyncratic reaction.

● Plateau iris syndrome (a developmental anomaly).

● A large or anteriorly displaced lens.

● Aqueous misdirection (in which aqueous humor fills the vitreous cavity instead of flowing

through the pupil, most commonly as a result of ophthalmic surgery).

● Choroidal hemorrhage or effusion.

● A space-occupying lesion in the posterior segment of the eyeball (such as a tumor or a gas

bubble placed during retinal surgery).

● Developmental syndromes causing fibrosis in the posterior segment of the eyeball

Pulling conditions include:

● Inflammation or blood in the angle itself that fibroses and contracts

● Neovascularization of the iris with a resulting fibrovascular membrane (most commonly seen

in poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or ophthalmic artery insufficiency)

● Abnormal corneal endothelial cell proliferation

● Prolonged shallowing of the anterior chamber resulting in iris-angle contact due to trauma

or surgery

● Epithelial cell or fibroblast invasion of the angle [4]

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The rapidity and degree of the intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation from angle-closure

determines whether symptoms occur. If the IOP rises quickly, as is typical of acute primary angle-

closure glaucoma, patients may experience some or all of the following symptoms:

● Decreased vision

● Halos around lights

● Headache

● Severe eye pain

● Nausea and vomiting

If the rise in IOP is slower and does not reach very high levels, the patient may be symptom-free.

This occurs in chronic angle-closure glaucoma. The patient may not notice damage to the

peripheral vision, which generally precedes decrease in central vision.

Signs that suggest a rapid rise in IOP include ( picture 2):

● Conjunctival redness

● Corneal edema or cloudiness

● A shallow anterior chamber

● A mid-dilated pupil (4 to 6 mm) that reacts poorly to light

Symptoms and signs of acute glaucoma often occur in the evening, when lower light levels cause

mydriasis and folds of the peripheral iris block the narrow angle [18].

DIAGNOSIS

Patients with the above symptoms or signs should undergo emergent examination of both eyes

by an ophthalmologist, including:

● Visual acuity

● Evaluation of the pupils

● Intraocular pressure (IOP)

● Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segments

● Visual field testing (either by confrontation [finger testing] or by formal methods, depending

on the acuity of the clinical situation)

● Gonioscopy (see 'Gonioscopy' below)

● Undilated fundus examination

Pupillary dilation should be deferred in untreated cases of suspected angle-closure glaucoma, as

this may exacerbate the condition.

On eye examination, patients who have experienced prior acute attacks of high IOP may

demonstrate iris irregularity due to ischemia during the attack, glaucomflecken (scattered

opacities) in the anterior lens, normal or increased IOP, and cupping of the optic disc if narrow-

angle glaucoma is present.

Although angle-closure often presents in just one eye, it is important to examine the other eye as

well. The angle of the fellow eye may be similarly narrow, putting this eye at risk for future angle-

closure attacks unless prophylactic treatment is instituted.

Diagnostic tests

Gonioscopy — Gonioscopy is the gold-standard method of diagnosing angle-closure

glaucoma. This technique involves using a special lens for the slit lamp, which allows the

ophthalmologist to visualize the angle ( picture 3). Indentation gonioscopy refers to putting

posterior pressure on the eyeball with the lens used for gonioscopy. The pressure will widen the

angle if it is not scarred completely closed; the extent to which scarring has produced angle-

closure helps to determine its severity and chronicity. Gonioscopy requires expertise and

experience to perform reliably.

Slit lamp grading of anterior chamber depth — In this technique, the width of the angle is

estimated by shining a light beam from the slit lamp on the peripheral anterior chamber. It is not

as reliable as gonioscopy for diagnosing angle-closure glaucoma.

Ultrasound biomicroscopy — Specialized ultrasound of the anterior chamber can show

angle-closure and help to define the mechanism. The ultrasound biomicroscope instrument is

costly and thus not widely available. This technique also requires specialized interpretation of the

results.

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography — High-definition anterior segment

optical coherence tomography is being used as a modality to image the drainage angle and

detect eyes at risk for angle-closure [19]. Findings suggest that eyes prone to developing angle-

closure do not merely differ anatomically from normal eyes but may also respond differently to

light stimuli [20]. As an example, when dilated to the same degree, the iris of an angle-closure

eye tends to be thicker than the iris of a normal eye [21].

Provocative tests — Provocative tests most often do not provide additional information

beyond the clinical examination and are not widely used because they are time-consuming, not

definitive, and potentially risky. In the dark room provocation test, a patient rests (awake) in a

dark room for 30 minutes with his or her head in the prone position to encourage pupillary

dilation and forward displacement of the lens. Angle-closure is suggested if the IOP rises

significantly or if the angle appears more closed on gonioscopy. Clinical applicability is unknown.

In pharmacologic tests, the pupil is dilated with phenylephrine or parasympatholytic mydriatic

eye drops and pilocarpine is instilled in an attempt to provoke an attack of angle-closure

glaucoma. This procedure involves risk and a negative result does not absolutely rule out angle-

closure [4]. Both eyes should not be tested simultaneously. We do not recommend this test.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Other causes of a red eye may mimic acute primary angle-closure glaucoma. These include iritis,

traumatic hyphema, conjunctivitis, episcleritis, subconjunctival hemorrhage, corneal abrasion,

and infectious keratitis. (See "Overview of the red eye".)

The primary care clinician may be able to distinguish acute primary closure from these

conditions by the presence of severe eye pain, headache, nausea and vomiting, a mid-dilated

pupil, and possibly decreased vision. However, not every patient with acute angle-closure

glaucoma will demonstrate all of these symptoms and signs.

Secondary angle-closure is best differentiated from primary angle-closure by an ophthalmologist

(see 'Secondary angle-closure' above). The management of these disorders differs from

treatment of primary angle-closure.

MANAGEMENT

Management of angle-closure glaucoma involves medical control of elevated intraocular

pressure (IOP) followed by reversal of angle-closure by laser peripheral iridotomy or other

surgical treatments. The patient should be referred urgently to an ophthalmologist for care (

table 2).

Acute primary angle-closure glaucoma

Medical therapy — There are no available trials comparing medical options for treatment of

acute angle-closure glaucoma, and treatment recommendations are based on clinical experience

[22]. When an ophthalmologist is available for consultation within one hour of patient

presentation, patients with signs or symptoms suggesting possible acute angle-closure should

be referred for emergency assessment and treatment.

When there is likely to be an hour or more delay before a patient can be seen by an

ophthalmologist, and the suspicion of an acute attack is high, empiric treatment should be

initiated. If the vision is normal, but other symptoms and signs suggest an acute angle-closure

attack, empiric treatment should only be given if the intraocular pressure is significantly elevated

(eg, >40 mmHg). For an acute primary angle-closure attack, initial management involves prompt

administration of pressure-lowering eye drops. A possible regimen would be one drop each, one

minute apart, of [22]:

● 0.5% timolol maleate;

● 1% apraclonidine; and

● 2% pilocarpine, especially immediately prior to laser peripheral iridotomy [2]

We also suggest giving the patient 500 mg of oral or intravenous (IV) acetazolamide. The eye

pressure should be checked 30 to 60 minutes after giving pressure-lowering drops and

acetazolamide. If the eye pressure is still significantly elevated, the same drops could be given

again, but the patient should also be examined immediately by an ophthalmologist. Systemic

medications other than acetazolamide (such as IV mannitol) should be administered under the

guidance of an ophthalmologist, since angle-closure should be confirmed before they are given.

If medical treatment is successful in reducing IOP, as is most often the case, corneal edema and

eye pain will typically lessen or resolve. In refractory cases, the ophthalmologist may consider

performing an anterior chamber paracentesis to remove some aqueous humor and immediately

lower the eye pressure temporarily, which may help to break the attack. Once the attack is

broken, the treatment of choice is a peripheral iridotomy. If laser peripheral iridotomy fails to

remain patent, or the cornea is too cloudy to visualize the iris, surgical peripheral iridectomy may

be necessary.

Laser peripheral iridotomy — This procedure creates a tiny hole in the peripheral iris

through which aqueous humor can flow and reach the angle [23]. Once the iridotomy is patent,

pupillary block is bypassed. A peripheral iridotomy is usually created with a laser.

The IOP is rechecked 30 to 120 minutes after the iridotomy is performed, and mild steroid drops

are given for several days. Repeat gonioscopy is then performed to determine if the angle is

wider. The pupil is dilated to ensure that the IOP does not rise significantly and to better assess

any glaucoma damage to the optic nerve.

Possible complications of laser peripheral iridotomy include:

● Increased IOP

● Inflammation

● Laser burns to the cornea, lens, or retina

● A ghost image in the vision

● Increased rate of cataract formation [24,25]

● Need for repeat treatment if the hole were to shrink or close spontaneously

The fellow eye should be examined. If a narrow angle is found, prophylactic laser peripheral

iridotomy should be performed to prevent future attacks of angle-closure glaucoma [24].

Untreated, approximately 50 percent of fellow eyes in acute angle-closure glaucoma patients will

have another attack within five years [24,26].

Surgical peripheral iridectomy — In this procedure, the ophthalmologist makes an incision

into the anterior chamber and surgically excises a small amount of iris tissue to create a passage

for aqueous humor to reach the angle.

Other surgery — In a few cases of angle-closure glaucoma, goniosynechialysis may be

performed in the operating room at some point after a peripheral iridotomy is in place. In

goniosynechialysis, adhesions that result in scarring of the angle are mechanically lysed in an

attempt to restore some drainage function. Results tend to be better if the scarring has been

present for less than one year [27].

Cataract surgery (phacoemulsification) with an intraocular lens implant may resolve the issue of

acute or chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma in some patients by removing the lens that may

be crowding the angle [24,28-30]. A randomized trial of 62 Chinese patients with cataracts who

had been medically treated for acute primary angle-closure glaucoma found that early

phacoemulsification was more effective than laser peripheral iridotomy in preventing recurrence

of IOP rise [31]. In a 2017 meta-analysis, patients with angle-closure glaucoma experienced a 6.4

mmHg (95% CI, -9.4 to -3.4 mmHg) lowering of IOP after cataract surgery at 12 months’ or longer

follow-up [32]. A multicenter study randomizing angle-closure patients to either clear lens

extraction (ie, lens removal without significant cataract) or laser peripheral iridotomy found that

clear lens extraction was more efficacious, with IOP 1.18 mmHg lower than after iridotomy (95%

CI -1.99 to -0.38), as well as more cost-effective [7].

Chronic angle-closure glaucoma — Laser peripheral iridotomy is the first step in treatment of

patients with chronic angle-closure glaucoma, to relieve any pupillary block component. The IOP

may remain elevated, however, if scarring has already damaged the drainage angle. In this case,

the remaining glaucoma is treated medically and surgically much as in open-angle glaucoma.

(See "Open-angle glaucoma: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis".)

Secondary angle-closure glaucoma — Secondary angle-closure glaucoma is managed by

treating the primary cause if possible. Controlling the IOP medically and surgically afterwards is

the next step, much as in open-angle glaucoma. (See "Open-angle glaucoma: Epidemiology,

clinical presentation, and diagnosis".)

MEDICATIONS WITH GLAUCOMA WARNINGS

There are many medications that carry warnings or contraindications regarding use in patients

with glaucoma. These warnings and contraindications are relevant regardless of whether or not

the patient is taking glaucoma medications; they are not drug-drug interactions.

These warnings can pose difficulties for clinicians, as potential adverse outcomes vary according

to the type of glaucoma (open versus narrow-angle) and the type of laser treatment (iridotomy

verus trabeculoplasty). Iridotomy may protect against certain medication effects, but its

protective effect varies among patients and over time and requires ophthalmological

confirmation. (See "Open-angle glaucoma: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis".)

These potential adverse effects are discussed separately. (See "Open-angle glaucoma:

Treatment", section on 'Use of medications with glaucoma warnings'.)

PATIENT INSTRUCTIONS

Patients who are known to have narrow angles but who have not yet undergone laser peripheral

iridotomy should avoid medicines that induce pupillary dilation and might provoke an angle-

closure attack. Such medicines include over-the-counter decongestants, motion sickness

medications, adrenergic agents, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anticholinergic agents (

table 1) [2]. Once laser peripheral iridotomy has been performed, these medications are no

longer contraindicated.

People with a family history of primary angle-closure glaucoma should undergo regular

screening eye examinations for this condition, particularly as they reach middle age. The

examining ophthalmologist should perform gonioscopy to assess for narrow angles, and

evidence of prior angle-closure glaucoma; laser peripheral iridotomy should be performed if

these are found.

PROGNOSIS

The outcomes of patients with angle-closure glaucoma depend on how early the disease is

detected. Because glaucoma damage to the optic nerve is generally not reversible and can occur

within a matter of hours in the case of an acute angle-closure attack, it is important that an

ophthalmologist see these patients urgently to provide prompt diagnosis and treatment.

The fellow eye also must be evaluated as prophylactic treatment with laser peripheral iridotomy

can prevent future angle-closure. The outcome for patients with secondary angle-closure

depends on its cause.

INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS

UpToDate offers two types of patient education materials, "The Basics" and "Beyond the Basics."

The Basics patient education pieces are written in plain language, at the 5th to 6th grade reading

level, and they answer the four or five key questions a patient might have about a given

condition. These articles are best for patients who want a general overview and who prefer short,

easy-to-read materials. Beyond the Basics patient education pieces are longer, more

sophisticated, and more detailed. These articles are written at the 10th to 12th grade reading level

and are best for patients who want in-depth information and are comfortable with some medical

jargon.

Here are the patient education articles that are relevant to this topic. We encourage you to print

or e-mail these topics to your patients. (You can also locate patient education articles on a variety

of subjects by searching on "patient info" and the keyword(s) of interest.)

● Basics topic (see "Patient education: Angle-closure glaucoma (The Basics)" and "Patient

education: Anesthesia for elective eye surgery (The Basics)")

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

● Glaucoma involves a characteristic atrophy of the optic nerve head ("cupping"), often with

peripheral vision defects. Angle-closure glaucoma is characterized by narrowing or closure of

the anterior chamber angle, leading to increased intraocular pressure (IOP) and damage to

the optic nerve. (See 'Definition and types' above.)

● Drainage of aqueous humor through the anterior angle is blocked by anatomic narrowing of

the angle in primary angle-closure glaucoma. Acute blockage is an ophthalmic emergency,

since vision loss and blindness may occur quickly. (See 'Primary angle-closure' above.)

● Patients with chronic angle-closure glaucoma may not develop increased IOP and

symptoms, and diagnosis may be delayed resulting in more vision loss than patients with

acute angle-closure glaucoma. (See 'Chronic angle-closure' above.)

● Secondary angle-closure is caused by a variety of processes that either push or pull the

anterior chamber angle closed. These may include fibrosis and scarring, drug reactions,

neovascularization, or mass. (See 'Secondary angle-closure' above.)

● Patients with acute angle-closure glaucoma present with vision loss, headache, severe eye

pain, light halos, nausea, and vomiting. Ocular exam reveals a red eye, corneal cloudiness or

edema, a shallow anterior chamber, and poorly reactive mid-dilated pupil. Urgent referral for

ophthalmology consultation is necessary in this setting. (See 'Clinical presentation' above.)

● Diagnosis of angle-closure glaucoma is established by gonioscopy. Provocative tests are not

recommended. The fellow eye should be examined as well as the affected eye. (See

'Diagnostic tests' above.)

● Patients with symptoms and signs suggesting an acute attack of angle-closure glaucoma

require emergency care by an ophthalmologist ( table 2). We recommend emergency use

of topical ophthalmic medications to reduce IOP (Grade 1C). These drugs may include a

beta-blocker, an alpha agonist, and an agent to produce miosis. We also suggest systemic

medication to decrease IOP, which may include oral or intravenous (IV) acetazolamide or IV

mannitol (Grade 2C). Once the acute attack is controlled, definitive treatment for angle-

closure glaucoma is a laser peripheral iridotomy, to provide a small drainage hole through

the iris, or cataract surgery. (See 'Management' above.)

● Patients with narrow anterior chamber angles who are awaiting surgery should be advised

to avoid decongestants and anticholinergic medications, which may precipitate an attack.

(See 'Patient instructions' above.)

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

REFERENCES

1. Prum BE Jr, Rosenberg LF, Gedde SJ, et al. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice

Pattern(®) Guidelines. Ophthalmology 2016; 123:P41.

2. Prum BE Jr, Herndon LW Jr, Moroi SE, et al. Primary Angle Closure Preferred Practice

Pattern(®) Guidelines. Ophthalmology 2016; 123:P1.

3. Pokhrel PK, Loftus SA. Ocular emergencies. Am Fam Physician 2007; 76:829.

4. See JLS, Chew PTK. Angle-closure Glaucoma. In: Ophthalmology, 3rd, Yanoff M, Duker JS (Ed

s), Mosby, 2009. p.1162.

5. Kingman S. Glaucoma is second leading cause of blindness globally. Bull World Health

Organ 2004; 82:887.

6. Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma

burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014;

121:2081.

7. Azuara-Blanco A, Burr J, Ramsay C, et al. Effectiveness of early lens extraction for the

treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma (EAGLE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet

2016; 388:1389.

8. Seitz DP, Campbell RJ, Bell CM, et al. Short-term exposure to antidepressant drugs and risk

of acute angle-closure glaucoma among older adults. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2012; 32:403.

9. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegul

atoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm398223.htm (Accessed on August 0

7, 2014).

10. Lai JS, Gangwani RA. Medication-induced acute angle closure attack. Hong Kong Med J 2012;

18:139.

11. Foster PJ, Johnson GJ. Glaucoma in China: how big is the problem? Br J Ophthalmol 2001;

85:1277.

12. Bourne RR, Sørensen KE, Klauber A, et al. Glaucoma in East Greenlandic Inuit--a population

survey in Ittoqqortoormiit (Scoresbysund). Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2001; 79:462.

13. Congdon N, Wang F, Tielsch JM. Issues in the epidemiology and population-based screening

of primary angle-closure glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol 1992; 36:411.

14. Congdon NG, Friedman DS. Angle-closure glaucoma: impact, etiology, diagnosis, and

treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2003; 14:70.

15. Wang JC, Chew PT. What is the direct cost of treatment of acute primary angle closure

glaucoma? The Singapore model. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004; 32:578.

16. Buhrmann RR, Quigley HA, Barron Y, et al. Prevalence of glaucoma in a rural East African

population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000; 41:40.

17. Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, et al. Epidemiology of angle-closure glaucoma:

prevalence, clinical types, and association with peripheral anterior chamber depth in the

Egna-Neumarket Glaucoma Study. Ophthalmology 2000; 107:998.

18. Leibowitz HM. The red eye. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:345.

19. Wong HT, Lim MC, Sakata LM, et al. High-definition optical coherence tomography imaging

of the iridocorneal angle of the eye. Arch Ophthalmol 2009; 127:256.

20. Guzman CP, Gong T, Nongpiur ME, et al. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography

parameters in subtypes of primary angle closure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013; 54:5281.

21. Quigley HA, Silver DM, Friedman DS, et al. Iris cross-sectional area decreases with pupil

dilation and its dynamic behavior is a risk factor in angle closure. J Glaucoma 2009; 18:173.

22. Shields SR. Managing eye disease in primary care. Part 3. When to refer for ophthalmologic

care. Postgrad Med 2000; 108:99.

23. Quigley HA. Glaucoma. Lancet 2011; 377:1367.

24. Saw SM, Gazzard G, Friedman DS. Interventions for angle-closure glaucoma: an evidence-

based update. Ophthalmology 2003; 110:1869.

25. Vijaya L, Asokan R, Panday M, George R. Is prophylactic laser peripheral iridotomy for

primary angle closure suspects a risk factor for cataract progression? The Chennai Eye

Disease Incidence Study. Br J Ophthalmol 2017; 101:665.

26. Edwards RS. Behaviour of the fellow eye in acute angle-closure glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol

1982; 66:576.

27. Allingham RR, Damji K, Freedman S, et al. Surgery of the anterior chamber and iris. In: Shiel

ds' Textbook of Glaucoma, 5th Ed, Shields MB (Ed), Lippincott, Philadelphia 2005. p.550.

28. Teekhasaenee C, Ritch R. Combined phacoemulsification and goniosynechialysis for

uncontrolled chronic angle-closure glaucoma after acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Ophthalmology 1999; 106:669.

29. Lai JS, Tham CC, Chan JC. The clinical outcomes of cataract extraction by

phacoemulsification in eyes with primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) and co-existing

cataract: a prospective case series. J Glaucoma 2006; 15:47.

30. Friedman DS, Vedula SS. Lens extraction for chronic angle-closure glaucoma. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2006; :CD005555.

31. Lam DS, Leung DY, Tham CC, et al. Randomized trial of early phacoemulsification versus

peripheral iridotomy to prevent intraocular pressure rise after acute primary angle closure.

Ophthalmology 2008; 115:1134.

32. Masis M, Mineault PJ, Phan E, Lin SC. The role of phacoemulsification in glaucoma therapy:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surv Ophthalmol 2018; 63:700.

Topic 6903 Version 41.0

Language Subscription and License Agreement

Policies Support Tag

Contact Us About Us

UpToDate News Mobile Access

Help & Training Demos

! " # $

Wolters Kluwer Health Emmi®

Facts & Comparisons® Lexicomp®

Medi-Span®

© 2020 UpToDate, Inc. and/or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved.

You might also like

- Angle-Closure Glaucoma - UpToDateDocument9 pagesAngle-Closure Glaucoma - UpToDateElaine June FielNo ratings yet

- Classification of GlaucomaDocument6 pagesClassification of GlaucomaAli Al.JuffairiNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma and Cataract - ContentannDocument20 pagesGlaucoma and Cataract - ContentannDR. KUMARASWAMI HEALTH CENTRE COLLEGE OF NURSING KANYAKUMARINo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument14 pagesGlaucomaWilliam SumoroNo ratings yet

- Acute Closed Angle Glaucoma GuideDocument6 pagesAcute Closed Angle Glaucoma GuideNgeridingNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma Diagnosis & Treatment GuideDocument42 pagesGlaucoma Diagnosis & Treatment GuideSaha DirllahNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument52 pagesGlaucomaEden NamwabaNo ratings yet

- GLAUCOMADocument10 pagesGLAUCOMAcarls burg a. resurreccionNo ratings yet

- GlaucomeaDocument21 pagesGlaucomeamalathiNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma OverviewDocument33 pagesGlaucoma Overviewc/risaaq yuusuf ColoowNo ratings yet

- Dr. Liesa Zulhidya, SP.M: GlaucomaDocument37 pagesDr. Liesa Zulhidya, SP.M: GlaucomaShapira alNo ratings yet

- Glaukoma Dan HipermetropiDocument6 pagesGlaukoma Dan HipermetropifuadaffanNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: Seminar OnDocument43 pagesGlaucoma: Seminar OnSanjay GarasiyaNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma Aqueous Humour DynamicsDocument25 pagesGlaucoma Aqueous Humour Dynamicspraveen joseNo ratings yet

- A Project ReportDocument80 pagesA Project ReportShakun VidyottamaNo ratings yet

- Chapter One Mohamed - SeadDocument12 pagesChapter One Mohamed - SeadAbdirahman Hassan MohamedNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument9 pagesGlaucomaNil NilNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: DefinitionDocument5 pagesGlaucoma: DefinitionDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- Urgencias OftalmológicasDocument20 pagesUrgencias OftalmológicasDaniela León CastilloNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma and Ocular HypertensionDocument6 pagesGlaucoma and Ocular HypertensionsoniasistNo ratings yet

- GLUACOMADocument43 pagesGLUACOMAJoanna RachelNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma 2023Document58 pagesGlaucoma 2023Abubakar JallohNo ratings yet

- Primary GlaucomaDocument118 pagesPrimary GlaucomaaswanfaqihNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: Mshangila B. MD, M.MedDocument41 pagesGlaucoma: Mshangila B. MD, M.MedCharles AnthonyNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument3 pagesGlaucomaAgustinus BethaNo ratings yet

- GLAUCOMa Edited2Document8 pagesGLAUCOMa Edited2Maki CabuenaNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma Case StudyDocument5 pagesGlaucoma Case StudyEdgel QuidolesNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: Defitaria Permatasari I11109005Document46 pagesGlaucoma: Defitaria Permatasari I11109005yusufharkianNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma OverviewDocument4 pagesGlaucoma OverviewSurya Cahyadi JunusNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma Word FileDocument34 pagesGlaucoma Word Fileanon_784834955100% (1)

- 1 SMDocument7 pages1 SMAriNo ratings yet

- Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma (AACG)Document11 pagesAcute Angle-Closure Glaucoma (AACG)Intan AliNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma Case StudyDocument5 pagesGlaucoma Case StudyEdgel QuidolesNo ratings yet

- GLAUCOMADocument5 pagesGLAUCOMArocioisabelacamposNo ratings yet

- Acute Angle Closure GlaucomaDocument17 pagesAcute Angle Closure GlaucomaOvidiu RusuNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma by MohammedDocument10 pagesGlaucoma by MohammedFiekc DjjfNo ratings yet

- GUIDELINES FOR MANAGING GLAUCOMADocument30 pagesGUIDELINES FOR MANAGING GLAUCOMAYunita Eka Putri DunggaNo ratings yet

- PassMed Notes EYE 2022Document56 pagesPassMed Notes EYE 2022Kiran ShahNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma 191024141130Document25 pagesGlaucoma 191024141130Broz100% (1)

- American Optometric Association. Glaucoma HTTP - WWW - Aoa.org - Glaucoma - Xml.Document8 pagesAmerican Optometric Association. Glaucoma HTTP - WWW - Aoa.org - Glaucoma - Xml.Adriana FallaNo ratings yet

- Colsed Angle Glaucoma: Anil Regmi Medical Student NGMCDocument27 pagesColsed Angle Glaucoma: Anil Regmi Medical Student NGMCRegmi AnilNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: Causes, Symptoms, Risks, and TreatmentDocument7 pagesGlaucoma: Causes, Symptoms, Risks, and TreatmentGraitaaNo ratings yet

- Angle Closure GlaucomaDocument10 pagesAngle Closure GlaucomaGreselda TandudjajaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Closed Angle Glaucoma - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument6 pagesChronic Closed Angle Glaucoma - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfAngel LimNo ratings yet

- SGD LBM 3 Modul MataDocument12 pagesSGD LBM 3 Modul MataMillatiazmi Maulida ArdianiNo ratings yet

- Dr. Md. Yeamli Khan: Mbbs (Dhaka) Do (Du) Fcps (Ophth)Document50 pagesDr. Md. Yeamli Khan: Mbbs (Dhaka) Do (Du) Fcps (Ophth)Kawshik SahaNo ratings yet

- 6.GlaucomaDocument52 pages6.GlaucomacreativejoburgNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument3 pagesGlaucomaPuviyarasiNo ratings yet

- Eye Docs GlaucomaDocument147 pagesEye Docs GlaucomaMuneeb ShahzadNo ratings yet

- 6 GlaucomaDocument13 pages6 GlaucomaElijah MagaiwaNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument6 pagesGlaucomaBasit AliNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument9 pagesGlaucomat2ybrkm5hwNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: by Tekia BuntynDocument18 pagesGlaucoma: by Tekia BuntynTekia BuntynNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma Guide: Types, Symptoms, Risks & TreatmentDocument3 pagesGlaucoma Guide: Types, Symptoms, Risks & TreatmentplethoraldorkNo ratings yet

- What Is Glaucoma?Document9 pagesWhat Is Glaucoma?Subhash Digambar VisalNo ratings yet

- Glaucoma: A Leading Cause of Irreversible BlindnessDocument22 pagesGlaucoma: A Leading Cause of Irreversible BlindnessVaishali SinghNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument15 pagesGlaucomapreethijojo20035582100% (5)

- Approach To The Adult With Acute Persistent Visual LossDocument17 pagesApproach To The Adult With Acute Persistent Visual LossMauricio SvNo ratings yet

- GlaucomaDocument30 pagesGlaucomaMarie Nelle Escriba Limpoco67% (3)

- Official Reprint From Uptodate ©2018 Uptodate, Inc. And/Or Its Affiliates. All Rights ReservedDocument27 pagesOfficial Reprint From Uptodate ©2018 Uptodate, Inc. And/Or Its Affiliates. All Rights ReservedGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Current Concept of Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) and NMO Spectrum DisordersDocument10 pagesCurrent Concept of Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) and NMO Spectrum DisordersGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- DR Flora Cairan Anak PDFDocument1 pageDR Flora Cairan Anak PDFGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Terapi Corticosteroid, Terapi AntifungalDocument9 pagesTerapi Corticosteroid, Terapi AntifungalGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Unconsciousness - DR Astra Dea SPS: General ExaminationDocument3 pagesUnconsciousness - DR Astra Dea SPS: General ExaminationGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Current Concept of Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) and NMO Spectrum DisordersDocument10 pagesCurrent Concept of Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) and NMO Spectrum DisordersGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- E RefdDocument13 pagesE RefdGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- JSFHDocument2 pagesJSFHGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- KJSDZDocument2 pagesKJSDZGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- W2case Objectives and Learning ObjectivesDocument23 pagesW2case Objectives and Learning ObjectivesGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- FSVXCDocument2 pagesFSVXCGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Case and Learning Objectives on Pregnancy PhysiologyDocument14 pagesCase and Learning Objectives on Pregnancy PhysiologyGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument1 pageScanned With CamscannerGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen PDFDocument2 pagesAcute Abdomen PDFGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- EndocrinebahancompreDocument3 pagesEndocrinebahancompreGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- FKHSCDocument2 pagesFKHSCGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- FSVXCDocument2 pagesFSVXCGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- GDBFDocument3 pagesGDBFGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- VXCDocument2 pagesVXCGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- KJSDZDocument2 pagesKJSDZGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Lower Reproductive Tract Bacterial Flora: AerobesDocument20 pagesLower Reproductive Tract Bacterial Flora: AerobesGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Vs ZCDocument13 pagesVs ZCGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- KJSDZDocument2 pagesKJSDZGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Cover CeDocument1 pageCover CeGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument1 pageAssignmentGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Respi 4Document3 pagesRespi 4Gabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- FSVXCDocument2 pagesFSVXCGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Stool Exam and Lab HepatitisDocument10 pagesStool Exam and Lab HepatitisGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- The Acute Abdomen: Chapter OutlineDocument19 pagesThe Acute Abdomen: Chapter OutlineGabriella TjondroNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Refractive Amblyopia Treatment Study: ATS7 Protocol 5-24-04Document15 pagesBilateral Refractive Amblyopia Treatment Study: ATS7 Protocol 5-24-04samchu21No ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors For Myopia Among School Children in Aba (Pdfdrive)Document109 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors For Myopia Among School Children in Aba (Pdfdrive)Esther AkwuruohaNo ratings yet

- Uveitis SlidesDocument42 pagesUveitis SlidesMariam QaisNo ratings yet

- Vertex Distance: Basic Optics, Chapter 7Document25 pagesVertex Distance: Basic Optics, Chapter 7PAM ALVARADONo ratings yet

- CataractDocument52 pagesCataracttammycristobalmd100% (4)

- Contact Lens Related Complications A Review-1Document20 pagesContact Lens Related Complications A Review-1Astri Dwi ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Letters To The EditorDocument8 pagesLetters To The EditorGheavita Chandra DewiNo ratings yet

- Ocular Disorders in The NewbornDocument11 pagesOcular Disorders in The NewbornXimena ParedesNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Visual ImpairmentDocument61 pagesModule 4 Visual ImpairmentMina Agarwal100% (5)

- Retinal DetachmentDocument3 pagesRetinal DetachmentzeejayNo ratings yet

- Vision Express, Gandhi Nagar, Hyderabad Andhra Sleek Ii Unit 1 Set 13.03.2013Document2 pagesVision Express, Gandhi Nagar, Hyderabad Andhra Sleek Ii Unit 1 Set 13.03.2013AbiNo ratings yet

- Strabismus Quick GuideDocument4 pagesStrabismus Quick Guideghitza80100% (1)

- Ocular Embryology Chamber Angle DevelopmentDocument2 pagesOcular Embryology Chamber Angle DevelopmentnabilahNo ratings yet

- Sudden Visual Loss - PPTX, MergencyDocument31 pagesSudden Visual Loss - PPTX, MergencyArsyil Ardiman MirwanNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Management of Patients With Eye andDocument86 pagesAssessment and Management of Patients With Eye andEsmareldah Henry SirueNo ratings yet

- Ijo 08 01 081Document8 pagesIjo 08 01 081Pretty ClarresaNo ratings yet

- Measuringintraocular Pressure PDFDocument7 pagesMeasuringintraocular Pressure PDFArgenis Bautista SánchezNo ratings yet

- 3D-19001205-Adlyn Firdaus Sopyan-Kodifikasi-Tugas 2Document3 pages3D-19001205-Adlyn Firdaus Sopyan-Kodifikasi-Tugas 2Anis KhoirunisaNo ratings yet

- Field Guide To Visual and Ophthalmic Optics (2004)Document125 pagesField Guide To Visual and Ophthalmic Optics (2004)Nikhil Maha Devan100% (1)

- Conjunctiva (Hira FJ)Document26 pagesConjunctiva (Hira FJ)Minahil ShahidNo ratings yet

- Clinical Approach To Optic Neuropathies: DiagnosisDocument14 pagesClinical Approach To Optic Neuropathies: Diagnosiskmathewjames100% (1)

- Efficacy and safety of focused ultrasound cycloplasty in glaucoma treatmentDocument3 pagesEfficacy and safety of focused ultrasound cycloplasty in glaucoma treatmentIris Del ÁngelNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Cataract SurgeryDocument196 pagesAtlas of Cataract SurgeryDaniel Fernández Gajardo100% (3)

- Change The Definition of BlindnessDocument5 pagesChange The Definition of BlindnessDelfi AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- ADNP Variant Summary TableDocument8 pagesADNP Variant Summary TableAngelica SalasNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Retinopathy by-DuaneBryantMDDocument7 pagesDiabetic Retinopathy by-DuaneBryantMDduanebryantmdNo ratings yet

- The Human EyeDocument9 pagesThe Human Eyegiana 4e100% (1)

- Fundoscopy Made Easy 3edDocument48 pagesFundoscopy Made Easy 3ednanaelseed100% (8)

- Anatomy and Physiology of The Human EyeDocument9 pagesAnatomy and Physiology of The Human EyeMaryy Basilio100% (2)

- Pelli-Robson & ETDRS Score Sheet & InstructionsDocument8 pagesPelli-Robson & ETDRS Score Sheet & InstructionsPaul H Artes100% (3)