Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hoover's Sign

Uploaded by

aladininsaneOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hoover's Sign

Uploaded by

aladininsaneCopyright:

Available Formats

50 PRACTICAL NEUROLOGY

Pract Neurol: first published as 10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00607.x on 1 October 2001. Downloaded from http://pn.bmj.com/ on February 6, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

N E U R O L O G I C A L S I G N

Hoover’s sign Jon Stone1 and Michael Sharpe2

Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Western General Hospital, Crewe Road,

Edinburgh. E-mail: jstone@skull.dcn.ed.ac.uk; 2Department of Psychological

Medicine, Royal Edinburgh Hospital, Morningside Park, Edinburgh

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY weakness from deliberately simulated weak-

It’s the middle of the clinic. Your next patient ness, which in our experience is a much rarer

has a bulging set of case notes problem outside medico-legal scenarios.

and struggles in to the room Dr Charles Franklin Hoover (1865–1927),

The great beauty on two elbow crutches with a physician in Cleveland, Ohio, described his

a hand-written list of 15 so- useful principle and two tests in the Journal

matic complaints. The worst of the American Medical Association in 1908

of Hoover’s sign symptom is progressive right (Hoover 1908). According to Pryse-Philips

leg weakness that has become 1995, Hoover trained as a Methodist minis-

so bad that any work has been ter before medical studies at Harvard, Vienna

is that it relies impossible for six months. and Strasbourg. He later became professor of

You have already noted some medicine at Western Reserve University, Ohio

physical signs. The right leg is specialising in pulmonary and hepatic dis-

on the absence dragged like a sack of potatoes ease. His neurological test should not be con-

and when the patient climbs fused with a respiratory ‘Hoover test’, which

on the bed the leg is hauled relates to paradoxical movement of the rib

of a normal phe- on with both hands. On di- cage in pericardial effusion. His article ‘A new

rect testing there is some ‘col- sign for the detection of malingering and

lapsing weakness’ even after functional paresis of the lower extremities’

nomenon found in you’ve cajoled and encour- (Hoover 1908) was based on four patients

aged the patient. The reflexes seen in two years. Hoover’s sign, like the type

are normal. How are you of patient for whom it is intended, has not

most people and going to clinch the diagnosis traditionally been popularised in neurologi-

of functional weakness? Can cal training or textbooks and yet it is one of the

Hoover’s sign help you? most useful and simple tests in this area.

not the presence Time to get some defini-

tions straight. In this article HOOVER’S SIGN

we will use the term func- Hoover’s two tests rely on the following prin-

of an abnormal tional weakness to refer to ciple – try it if you don’t believe us. If a healthy

medically unexplained weak- person, lying or sitting down, flexes their right

ness of the type that was hip, they will automatically extend their left

phenomenon formerly labelled ‘hysterical’, hip. This also occurs in hemiparesis due to an

i.e. the patient is unaware or upper motor neurone lesion – where hip ex-

largely unaware of any degree tension is invariably well preserved – and in

such as the Babin- of control over the symp- patients who have functional weakness.

tom. As we will comment This basic principle can be used to aid di-

later, Hoover’s sign does not agnosis in two main ways – both described by

ski sign. help differentiate this type of Hoover:

© 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd

OCT 2001 51

Pract Neurol: first published as 10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00607.x on 1 October 2001. Downloaded from http://pn.bmj.com/ on February 6, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

• For a patient with weakness of hip flexion:

Ask the patient to flex their weak leg at the

hip. In normal people and in patients with an

organic hemiparesis you will feel downward

pressure under the opposite heel. If you feel

nothing it suggests a functional weakness, i.e.

that effort is not being transmitted to either leg.

This sign can be used even if both legs are weak

but is probably less reliable than the next test.

• For a patient with weakness of hip extension:

You have already found weakness of hip exten-

sion on direct voluntary testing. Ask the patient

to flex their good leg against resistance while

keeping your hand under the heel of the weak

leg. If you feel downward pressure that was not

there before you have palpable evidence of in-

consistency in the examination. (Fig. 1).

The great beauty of Hoover’s sign is firstly,

that it relies on the absence of a normal phe-

nomenon found in most people and not the

presence of an abnormal phenomenon (such

as the Babinski sign). Secondly, it is a clinical

marker of internal inconsistency that can be

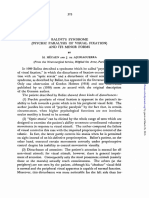

repeated in a controlled way and does not rely Figure 1 Hoover’s sign – how to do it. (a)

on skilled surreptitious observation. Thirdly, The patient is unable to extend the hip and

and perhaps more controversially, it is a phys- to press the heel into the bed on request.

ical sign, which if carefully handled, can be (b) The hip is extended involuntarily when

used to demonstrate to the patient their own the opposite leg is lifted off the bed. Re-

potential for recovery. printed from Neurology: an illustrated col-

our text, Fuller and Manford, p116, 1999,

PHYSIOLOGY by permission of the publisher Churchill

Why does this phenomenon exist? A simple Livingstone.

answer might be that for every action there

is an equal and opposite reaction. Imagine

you’ve just stepped on a pin. Because you have

probably lifted and flexed your leg, it helps if

the hamstrings of your other leg contract and

keep you planted on the floor. Walking is more

complicated but does rely on this basic re-

sponse. Sherrington first described and named

this the crossed extensor reflex (Sherrington

1910). He demonstrated its presence even in

decerebrate and spinal cord animals. The path-

way for this reflex involves excitatory spinal in-

terneurones, which traverse multiple levels of

the spinal cord before producing an antago-

nistic contraction in the opposite limb.

THREE IMPORTANT CAVEATS

Like any physical sign it is important not to get

too carried away by Hoover’s tests.

1 A positive Hoover test does not exclude dis-

© 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd

52 PRACTICAL NEUROLOGY

Pract Neurol: first published as 10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00607.x on 1 October 2001. Downloaded from http://pn.bmj.com/ on February 6, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

ease. It simply suggests that the majority of the ieff et al. 1961 examined the Hoover princi-

weakness you are observing is not due to dis- ple in several patients with functional weak-

ease. Weakness in organic disease like multi- ness using EMG and what amounts to a set of

ple sclerosis may be exaggerated for a number bathroom scales but did not reach new con-

of reasons: for example the patient is not sure clusions. Archibald & Wiechec 1970 carried

whether you believe them and wants to prove out a similar study in 12 normal patients, six

they are weak, the patient is distressed and organic hemiparetics, 11 patients with ‘vari-

finds it hard to exert maximal effort, or they ous neuromuscular disabilities’ and two with

do not understand your instructions. functional weakness. The study is disappoint-

2 A positive Hoover test does not tell you if ing because they only provided data on one

the person is ‘putting on’ the weakness. There comparison between functional and organic

is still no reliable way of differentiating those weakness and only examined Hoover’s test

patients who are deliberately deceiving you for weakness of hip flexion. They found retest

from the majority of patients who have little and between-patient inconsistencies in the

conscious control over their leg weakness. normal and organic groups (‘a reliablity coef-

This difficult judgement has to be based on ficient of 0.56’) when measuring downward

other criteria which are hard to come by, such heel pressure during contralateral leg raising.

as evidence of lying in the history, video sur- This variation is hardly surprising given the

veillance or a clear desire for substantial mon- population being studied, but it doesn’t help

etary gain. at all in validating the test in patients with

3 Be careful in the presence of pain. Pain may functional weakness, for whom the test is in-

affect the sign in several ways. Arieff reported tended.

a patient with ‘left sciatic radiculitis’ who had More recently, Ziv et al. 1998 carried out a

a positive Hoover test in their normal leg (Ari- controlled study of Hoover’s sign in nine pa-

eff 1961). The downward pressure exerted by tients with functional limb weakness, seven

their normal leg was greater when they tried with organic causes for weakness, and in 10

Figure 2 A controlled study to lift their painful leg than when they had healthy controls. They refined the test using

of Hoover’s sign – figures performed it in isolation. They interpreted computerized myometry – essentially a strain

adapted from Ziv et al. this as increased effort to aid the movement gauge measuring voluntary vs. involuntary

1998. A unique discrep- of a painful limb. Conversely, a patient may hip extension as described above. They found

ancy is observed in the be consciously reluctant to move a painful, leg this method could discriminate impressively

affected weak limbs of which could create a false positive test in the between ‘nonorganic’ and ‘organic’ leg weak-

patients with ‘nonorganic’ affected limb. Hoover’s has been described as ness when applied to a ‘gold standard’ of clini-

weakness, in contrast to a test for ‘nonorganic’ sciatica (Zalejski 1967) cal diagnosis backed up with laboratory and

their unaffected limb, nor- but we would not recommend this. imaging investigations (Fig. 2). Diukova et al.

mal controls and patients 2001 have recently replicated this finding in

with ‘organic’ weakness VALIDITY nine subjects using simple weighing scales.

(Error bars represent 95% We are aware of only four subsequent papers In this study, comparison groups with back

confidence intervals). on Hoover’s sign used to detect weakness. Ar- pain, neurological weakness and healthy con-

trols were significantly discriminated against.

We must bear in mind though that neither of

these studies were blinded and even weighing

scales do not necessarily equate with busy cli-

nicians using the sign in the real world. Clear-

ly more work is needed.

HOOVER’S SIGN IN THE ARMS?

Hoover commented that the phenomenon of

‘complementary opposition’ is also present in

the movements of shoulder abduction and

adduction although admitted it is less relia-

bly so. Ziv et al. 1998 investigated this with

© 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd

OCT 2001 53

Pract Neurol: first published as 10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00607.x on 1 October 2001. Downloaded from http://pn.bmj.com/ on February 6, 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

their technique. They obtained similar results CONCLUSIONS

to those in the leg but it remains to be seen Hoover’s sign is an easy sign to learn and

whether this result can be repeated or trans- use. Once learned, it will not be long before

lated into clinical practice. you have an opportunity to try it out on some-

one – in the light of a thorough history of

OTHER PHYSICAL SIGNS OF FUNC- course. None of the physical signs of ‘function-

TIONAL WEAKNESS al’ weakness has much more to commend it

How does Hoover’s sign measure up to than common sense. In our opinion Hoover’s

other competing signs? In his original arti- sign is, despite all our caveats,

cle, Hoover commented that he had ‘found the most useful.

Babinski’s sign unsatisfactory’ in relation to Hoover’s sign is

making a positive diagnosis of functional REFERENCES

weakness (Hoover 1908). Babinski would Archibald KC & Wiechec F (1970) A re-

have been the first to point out that his

appraisal of Hoover’s test. Archives

of Physical Medical Rehabilitation, an easy sign to

sign is absent in numerous organic causes of 51, 234–8.

leg weakness, such as myopathy and radicu- Arieff AJ, Tigay EI, Kurtz JF, Larmon

lopathy, and therefore had good specificity WA (1961) The Hoover sign: an ob-

jective sign of pain and/or weakness

learn and use.

but poor sensitivity for excluding functional in the back or lower extremities. Ar-

weakness. Collapsing weakness has been in- chives of Neurology, 5, 673–8.

vestigated on a few occasions over the years Diukova G, Liachovitskaia NI, Begliar-

ova AM & Vein AM (2001) Simple

Once learned, it

in neurophysiological ways (McComas et al.

quantitative analysis of the Hoo-

1983; Knutsson & Martensson 1985; van der

Ploeg & Oosterhuis 1991), but not as a clini-

ver’s test in patients with psycho-

genic and organic paresis . Journal will not be long

cal sign. One of the very few studies to of Neurological Science, 187, S108.

look at the frequency of collapsing weak- (Abstract)

ness in neurological populations was car-

Gould R, Miller BL, Goldberg MA

& Benson DF (1986) The validity

before you have

ried out by Gould et al. 1986. In a salutary of hysterical signs and symptoms.

if crude paper, a third of 30 patients with Journal of Nerv Ment Disease, 174,

acute organic neurological problems (most- 593–7.

Hoover CF (1908) A new sign for the

an opportunity to

ly stroke) had collapsing weakness on ad-

detection of malingering and func-

mission – no doubt due to a variety of

reasons such as pain, general illness and dif-

tional paresis of the lower extremi-

ties. Journal of the American Medi-

cal Association, 51, 746–7.

try it out on some-

ficulty following instructions.

Knutsson E & Martensson A (1985)

HOOVER’S SIGN AS A THERAPEUTIC

Isokinetic measurements of mus-

cle strength in hysterical paresis. one.

PROCEDURE? Electroencephalography and Clini-

In the course of examining many patients cal Neurophysiology, 61, 370–4.

McComas AJ, Kereshi S & Quinlan J (1983) A method for de-

with functional weakness we have recently

tecting functional weakness. Journal of Neurology, Neu-

found that some patients are interested to rosurgery and Psychiatry, 46, 280–2.

know precisely how we arrive at our diagno- van der Ploeg RJ & Oosterhuis HJ (1991) The ‘make/break

sis. In several patients, the demonstration of test’ as a diagnostic tool in functional weakness. Journal

their own Hoover’s sign has allowed the pa- of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 54, 248–51.

Pryse-Phillips W. (1995) Hoover, Charles Franklin. In: Com-

tient to see that, under some circumstances, panion to Clinical Neurology, p. 422. Little, Brown, Bos-

they are able to achieve greater power in their ton.

affected leg than they thought possible. Han- Sherrington CS (1910) Flexion-reflex of the limb, crossed

dled carefully, this seems to help their under- extension reflex, and reflex stepping and standing. Jour-

nal of Physiological (London), 40, 28–121.

standing of the problem, their belief that their Zalejski S (1967) Hoover’s sign in the diagnosis of sciatica.

leg can get better, and improves transparency Wiad Lek, 20, 35–9.

and trust between doctor and patient. Han- Ziv I, Djaldetti R, Zoldan Y, Avraham M & Melamed E (1998)

dled badly, the patient may well interpret your Diagnosis of ‘non-organic’ limb paresis by a novel ob-

jective motor assessment: the quantitative Hoover’s test.

explanation as ‘Gotcha!’. Therein lies the chal-

Journal of Neurology, 245, 797–802.

lenge.

© 2001 Blackwell Science Ltd

You might also like

- Hoover's SignDocument4 pagesHoover's Signjawad.melhemNo ratings yet

- Clinical Aspects of Sleep and Sleep DisturbanceFrom EverandClinical Aspects of Sleep and Sleep DisturbanceTerrence L. RileyNo ratings yet

- On the Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in FemalesFrom EverandOn the Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in FemalesNo ratings yet

- Report of CaseDocument3 pagesReport of CasefransAPNo ratings yet

- Consciousness Beyond the Body: Evidence and ReflectionsFrom EverandConsciousness Beyond the Body: Evidence and ReflectionsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- OBE Veridicality ResearchDocument6 pagesOBE Veridicality ResearchKarina PsNo ratings yet

- Restless Legs Syndrome: Relief and Hope for Sleepless Victims of a Hidden EpidemicFrom EverandRestless Legs Syndrome: Relief and Hope for Sleepless Victims of a Hidden EpidemicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Snapping Hip SyndromeDocument6 pagesThe Snapping Hip SyndromeFlorin MacarieNo ratings yet

- The New Neurotology: A Comprehensive Clinical GuideFrom EverandThe New Neurotology: A Comprehensive Clinical GuideNo ratings yet

- Case 1. B. R., A White Female, 22: Arthur King, M.D., and Frank B. Walsh, M.DDocument5 pagesCase 1. B. R., A White Female, 22: Arthur King, M.D., and Frank B. Walsh, M.Dnico_nucciNo ratings yet

- Functional Limb Weakness and ParalysisDocument16 pagesFunctional Limb Weakness and Paralysis955g7sxb8pNo ratings yet

- conversion disorderDocument12 pagesconversion disorderJahanvi MishraNo ratings yet

- The Vagus-Immune Connection: Harness Your Vagus Nerve to Manage Stress, Prevent Immune Dysregulation, and Avoid Chronic DiseaseFrom EverandThe Vagus-Immune Connection: Harness Your Vagus Nerve to Manage Stress, Prevent Immune Dysregulation, and Avoid Chronic DiseaseNo ratings yet

- Sperry 1968Document11 pagesSperry 1968Azma IsmailNo ratings yet

- Algoritmo diferencial de debilidad proximal en paciente con miopatia adquirida por nemalina.Document7 pagesAlgoritmo diferencial de debilidad proximal en paciente con miopatia adquirida por nemalina.Farid Santiago Abedrabbo LombeydaNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of Cauda Equina SyndromeDocument5 pagesA Case Study of Cauda Equina SyndromeProfessor Stephen D. Waner100% (5)

- Hugo Liepmann, Parkinson'S Disease and Upper Limb Apraxia: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesHugo Liepmann, Parkinson'S Disease and Upper Limb Apraxia: SciencedirectDiretoria CientíficaNo ratings yet

- The Primary Care of Seizure Disorders: A Practical Guide to the Evaluation and Comprehensive Management of Seizure DisordersFrom EverandThe Primary Care of Seizure Disorders: A Practical Guide to the Evaluation and Comprehensive Management of Seizure DisordersNo ratings yet

- The Rebound Phenomenon Gordon Holmes: (Here "Recoil") (1) Limbs, (2) Limbs, (3) I, Injuries Reflex, WordsDocument1 pageThe Rebound Phenomenon Gordon Holmes: (Here "Recoil") (1) Limbs, (2) Limbs, (3) I, Injuries Reflex, WordsIlham JauhariNo ratings yet

- Strub 1989Document4 pagesStrub 1989mgobiNo ratings yet

- Great Feuds in Medicine: Ten of the Liveliest Disputes EverFrom EverandGreat Feuds in Medicine: Ten of the Liveliest Disputes EverRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (19)

- Moldaver Tourniquet Paralysis SyndromeDocument9 pagesMoldaver Tourniquet Paralysis Syndromeasi basseyNo ratings yet

- John G. Broadbent v. Patricia Roberts Harris Secretary of Health, and Human Services, 698 F.2d 407, 10th Cir. (1983)Document10 pagesJohn G. Broadbent v. Patricia Roberts Harris Secretary of Health, and Human Services, 698 F.2d 407, 10th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Study of Phantom Limb After Right Hemisphere Stroke: ThreeDocument8 pagesStudy of Phantom Limb After Right Hemisphere Stroke: ThreeFlorina SudituNo ratings yet

- S Chu Knecht 1969Document14 pagesS Chu Knecht 1969camila torresNo ratings yet

- Lewy Body Dementia: Case Report and DiscussionDocument6 pagesLewy Body Dementia: Case Report and DiscussionHensy Virginia SolonNo ratings yet

- Human Kluver-Bucy: SyndromeDocument6 pagesHuman Kluver-Bucy: SyndromeFlorencia RubioNo ratings yet

- Abductor Sign: A Reliable New Sign To Detect Unilateral Non-Organic Paresis of The Lower LimbDocument6 pagesAbductor Sign: A Reliable New Sign To Detect Unilateral Non-Organic Paresis of The Lower LimbThein Htun NaungNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of Hysteria - A Selection of Classic Articles on the Analysis and Symptoms of HysteriaFrom EverandThe Psychology of Hysteria - A Selection of Classic Articles on the Analysis and Symptoms of HysteriaNo ratings yet

- Balint's Syndrome (Psychic Paralysis of Visual Fixation) and Its Minor FormsDocument28 pagesBalint's Syndrome (Psychic Paralysis of Visual Fixation) and Its Minor FormsJulian GorositoNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychological Studies of Apraxia and Related DisordersFrom EverandNeuropsychological Studies of Apraxia and Related DisordersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Disconnection Syndromes in Animals and ManDocument60 pagesDisconnection Syndromes in Animals and ManJorge BorraniNo ratings yet

- Herssens Et Al. 2021 - Paving The Way Toward Distinguishing Fallers From Non-Fallers in Bilateral VestibulopathyDocument22 pagesHerssens Et Al. 2021 - Paving The Way Toward Distinguishing Fallers From Non-Fallers in Bilateral VestibulopathyHerr FrauNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Tremor.11Document16 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Tremor.11Stephanie Queiroz Dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Epigenetics: The Death of the Genetic Theory of Disease TransmissionFrom EverandEpigenetics: The Death of the Genetic Theory of Disease TransmissionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Clinical Anatomy of the Vestibular SystemDocument21 pagesClinical Anatomy of the Vestibular Systemaditya febriansyahNo ratings yet

- Journal RombergDocument7 pagesJournal RombergAnonymousssNo ratings yet

- Kugelberg-Welander Syndrome ReportDocument4 pagesKugelberg-Welander Syndrome ReportAionesei VasileNo ratings yet

- Lumbar Facet Syndrome - BogdukDocument8 pagesLumbar Facet Syndrome - BogdukSamSchroetkeNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Song of the Cell By Siddhartha Mukherjee: An Exploration of Medicine and the New HumanFrom EverandSummary of The Song of the Cell By Siddhartha Mukherjee: An Exploration of Medicine and the New HumanRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Practice Applied T 00 Hazzi A LaDocument452 pagesPractice Applied T 00 Hazzi A LaСергій Osteopathy ШАНОNo ratings yet

- Orthopediatric LWWDocument398 pagesOrthopediatric LWWかちえ ちょうNo ratings yet

- Epilepsia CursivaDocument3 pagesEpilepsia Cursiva---No ratings yet

- Definicion y Clasificacion EpilepsiaDocument9 pagesDefinicion y Clasificacion EpilepsiaBatgirl xoxoNo ratings yet

- Review ArticleDocument17 pagesReview ArticleLinda Jeanette Angelina MontungNo ratings yet

- Lower Back Pain - MontaltoDocument5 pagesLower Back Pain - MontaltoElizabeth OxfordNo ratings yet

- The Peroneal Tendons: A Clinical Guide to Evaluation and ManagementFrom EverandThe Peroneal Tendons: A Clinical Guide to Evaluation and ManagementMark SobelNo ratings yet

- The Cure of Imperfect Sight by Treatment Without Glasses: IllustratedFrom EverandThe Cure of Imperfect Sight by Treatment Without Glasses: IllustratedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Pusher SYndrome Understanding and TreatingDocument9 pagesPusher SYndrome Understanding and TreatingJason ColeNo ratings yet

- The Value of The History of AnaesthesiaDocument5 pagesThe Value of The History of Anaesthesiamono011019No ratings yet

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Syndrome, Diagnostics and Treatment: Nature Reviews Neurology August 2009Document13 pagesLumbar Spinal Stenosis: Syndrome, Diagnostics and Treatment: Nature Reviews Neurology August 2009Surya PangeranNo ratings yet

- Selected Topics: Toxicology: Propofol-Induced Seizure-Like PhenomenaDocument3 pagesSelected Topics: Toxicology: Propofol-Induced Seizure-Like PhenomenaRenan Toledo SandaloNo ratings yet

- VPPBDocument14 pagesVPPBCarla Gómez BrionesNo ratings yet

- LBP Case ReportDocument4 pagesLBP Case ReportMichele MarengoNo ratings yet

- Let Your Life Speak Listening For The Voice of VocationDocument16 pagesLet Your Life Speak Listening For The Voice of VocationaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Casio FX-9700GH Calculator ManualDocument188 pagesCasio FX-9700GH Calculator ManualLuna StoneNo ratings yet

- Johari WindowDocument5 pagesJohari WindowgustavNo ratings yet

- How To Teach Children With ADHD:: Classroom Challenges and SolutionsDocument1 pageHow To Teach Children With ADHD:: Classroom Challenges and SolutionsaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Language Matters StigmaDocument1 pageLanguage Matters StigmaaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Insightful Analysis of Proverbs Compares Ancient Wisdom LiteratureDocument3 pagesInsightful Analysis of Proverbs Compares Ancient Wisdom LiteraturealadininsaneNo ratings yet

- Excoriation FaqDocument1 pageExcoriation FaqaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- RhinocerosDocument2 pagesRhinocerosaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- 10 Questions For Michelle WilliamsDocument1 page10 Questions For Michelle WilliamsaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- 10 Must-See Movies About Alzheimer'sDocument3 pages10 Must-See Movies About Alzheimer'saladininsaneNo ratings yet

- SkimmingDocument2 pagesSkimmingapi-170611830No ratings yet

- Mark VonegatDocument4 pagesMark VonegataladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Airfresheners PDFDocument16 pagesAirfresheners PDFaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Kako Narezati 900MB Na CD-R PDFDocument2 pagesKako Narezati 900MB Na CD-R PDFDanielTomicNo ratings yet

- May2001 MoviesDocument1 pageMay2001 MoviesaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- BAP TS W MitchellDocument11 pagesBAP TS W MitchellaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Dialogos AidaDocument195 pagesDialogos AidaaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- ElevatorDocument2 pagesElevatoraladininsaneNo ratings yet

- DbtFaq ConsDocument6 pagesDbtFaq ConssenorlealNo ratings yet

- Cohen QuoteDocument1 pageCohen QuotealadininsaneNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of Jung in Hermann Hesse Work'sDocument13 pagesThe Psychology of Jung in Hermann Hesse Work'sAlejandra Figueroa100% (1)

- Internet Gaming Disorder Fact SheetDocument1 pageInternet Gaming Disorder Fact SheetCojocaru IonutNo ratings yet

- DrivingDocument1 pageDrivingaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- MNTYSNGSDocument23 pagesMNTYSNGSaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Forget About ItDocument1 pageForget About ItaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- ExcusesDocument2 pagesExcusesaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- Grief CycleDocument3 pagesGrief CyclealadininsaneNo ratings yet

- Thalaivar QuotesDocument4 pagesThalaivar QuotesNandha KishoreNo ratings yet

- Footprints in The SandDocument1 pageFootprints in The SandaladininsaneNo ratings yet

- PED011 Final Req 15Document3 pagesPED011 Final Req 15macabalang.yd501No ratings yet

- Final OcTa Nov 16 OCTA Research Monitoring ReportDocument36 pagesFinal OcTa Nov 16 OCTA Research Monitoring ReportRappler100% (1)

- Overcome Anxiety, Depression and Gain ControlDocument3 pagesOvercome Anxiety, Depression and Gain ControlPranavNo ratings yet

- Unmanned Systems in Support of Future Medical Operations in Dense Urban EnvironmentsDocument28 pagesUnmanned Systems in Support of Future Medical Operations in Dense Urban EnvironmentsEdy JjNo ratings yet

- Topic: Avicenna (Ibn Sina) : Presentation By: Anar HashimliDocument7 pagesTopic: Avicenna (Ibn Sina) : Presentation By: Anar HashimlianarNo ratings yet

- MCC 34 DomperidoneDocument40 pagesMCC 34 DomperidoneAnonymous PTSx0GANo ratings yet

- Jan Aushadhi SchemeDocument10 pagesJan Aushadhi SchemeSUSHMA MURALIENo ratings yet

- Healthcare Should Not Be Provided For Free Regardless of A PersonDocument1 pageHealthcare Should Not Be Provided For Free Regardless of A PersonLinh ChiNo ratings yet

- Researchers and by Clinicians For Use With Their PatientsDocument3 pagesResearchers and by Clinicians For Use With Their PatientsAnton Henry MiagaNo ratings yet

- Automated Detection of COVID 19 From X Ray Images Using CNN and Android MobileDocument8 pagesAutomated Detection of COVID 19 From X Ray Images Using CNN and Android MobileasdNo ratings yet

- Amrik PED SURGDocument24 pagesAmrik PED SURGAditya DharmajiNo ratings yet

- Bonardi2017 - Cópia PDFDocument11 pagesBonardi2017 - Cópia PDFRENATO SUDATINo ratings yet

- Yield of Thoracoscopic Biopsy Truenat in The Diagnosis of Tubercular Pleural EffusionDocument7 pagesYield of Thoracoscopic Biopsy Truenat in The Diagnosis of Tubercular Pleural EffusionThomas KurianNo ratings yet

- 3305 Alanya - Gezi - Rehberi 2011 58sDocument58 pages3305 Alanya - Gezi - Rehberi 2011 58sAnıl KaraağaçNo ratings yet

- Organ Function Mons Veneris: Labia MinoraDocument5 pagesOrgan Function Mons Veneris: Labia MinoraSabana MedtimbangNo ratings yet

- Permit To Work FormsDocument8 pagesPermit To Work FormsMarc Vincent SeñorinNo ratings yet

- KS3 Science Revision - Worksheets With AnswersDocument108 pagesKS3 Science Revision - Worksheets With AnswersTony TitanicNo ratings yet

- Detection of Marine Microalgae (Phytoplankton) Quality To Support Seafood Health: A Case Study On The West Coast of South Sulawesi, IndonesiaDocument8 pagesDetection of Marine Microalgae (Phytoplankton) Quality To Support Seafood Health: A Case Study On The West Coast of South Sulawesi, IndonesiaIndah AdeliaNo ratings yet

- WDR22 Booklet 1Document74 pagesWDR22 Booklet 1Khánh Hoàng NamNo ratings yet

- DUPHAT 2016 LeafletDocument2 pagesDUPHAT 2016 LeafletIPSF EMRONo ratings yet

- The Body Never Lies PDFDocument5 pagesThe Body Never Lies PDFhmyzone55No ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study On Stressors Stress Symptoms and Coping Mechanisms Among High School Students PASCALDocument47 pagesA Qualitative Study On Stressors Stress Symptoms and Coping Mechanisms Among High School Students PASCALASh tabaog0% (1)

- Boys WH Swim Results 9.14Document4 pagesBoys WH Swim Results 9.14The LedgerNo ratings yet

- Circadian Rhythms and Sleep Cycles ExplainedDocument14 pagesCircadian Rhythms and Sleep Cycles ExplainedSi sielNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis MataDocument168 pagesDiagnosis Mata19. Moh Hidayatullah AL AhyaNo ratings yet

- EKG Intermediate Tips Tricks ToolsDocument55 pagesEKG Intermediate Tips Tricks Toolsmayas bsharatNo ratings yet

- Microbank™-Dry: Product Code Pl.172Document2 pagesMicrobank™-Dry: Product Code Pl.172Fadhlan ArifinNo ratings yet

- Unlocking The Mysteries of DeafBlind InterpretingDocument74 pagesUnlocking The Mysteries of DeafBlind InterpretingMark Niño A. BrunoNo ratings yet

- Tsinghua GSS 2022 Essay SubmissionDocument6 pagesTsinghua GSS 2022 Essay SubmissionNgọc BùiNo ratings yet

- Play Therapy To Reduce Anxiety in Children: Wahyu - Endang.setyowati-2020@fkp - Unair.ac - IdDocument24 pagesPlay Therapy To Reduce Anxiety in Children: Wahyu - Endang.setyowati-2020@fkp - Unair.ac - IdbbpcheeseNo ratings yet