Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Motions

Uploaded by

T RodOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Motions

Uploaded by

T RodCopyright:

Available Formats

Selected Criminal Terminology

“APPRENDI.” This federal constitution requirement states that

sentencing enhancements (other than prior convictions) must be decided by the

jury. “Other than the fact of a prior conviction, any fact that increases the penalty

for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum must be submitted to a jury

and proved beyond a reasonable doubt.” Apprendi v. New Jersey (2000) 530

U.S. 466, 490 (147 L.Ed.2d 435, 120 S.Ct. 2348. *

“ARANDA.” People v. Aranda (1965) 63 Cal.2d 518. See Bruton v. United

States (1968) 391 U.S. 123 [20 L.Ed.2d 476, 88 S.Ct. 1620]. In a joint trial, co-

defendant's statement must be excluded or edited if it incriminates another co-

defendant. The rule thus presumes the statement is an admissible admission by

the declarant and inadmissible hearsay against the codefendant. People v.

Fletcher (1996) 13 Cal.4th 451, 455. Aranda held that the codefendant’s

confession may be introduced a the joint trial if it can be edited to eliminate

references to the defendant without prejudice to the confessing codefendant. (63

Cal.2d at pp. 530-531). If not, and the prosecution insists on introducing the

confession, the trial court must sever the trial. (Ibid.)*

“ARBUCKLE.” People v. Arbuckle (1978) 22 Cal.3d 749. Right of a

defendant to be sentenced by the same judge who accepted his guilty plea. In

Arbuckle, our Supreme Court held as a general principle, “whenever a judge

accepts a plea bargain and retains sentencing discretion under the agreement,

an implied term of the bargain is that sentence will be imposed by that judge.

Because of the range of dispositions available to a sentencing judge, the

propensity in sentencing demonstrated by a particular judge is an inherently

significant factor in the defendant's decision to enter a guilty plea. Thus, the

sentence imposed by a judge other than the one who took the plea cannot be

allowed to stand.” In re Mark L. (1983) 34 Cal.3d 171, 177*

“BOYKIN/TAHL” Boykin v. Alabama (1969) 392 U.S. 238; In re Tahl

(1969) 1 Cal.3d 122. The defendant must be advised of the constitutional rights

to a jury trial, confrontation and against self incrimination and expressly waive

those rights on the record when entering a guilty or no contest plea.*

“BRACAMONTE MOTION” People v. Bracamonte (1981) 119 Cal.App.3d

644. This is a motion to bifurcate the trial on the principal crimes from the trial on

the defendant’s prior convictions alleged for enhancement purposes. *

“BRADY.” Brady v. Maryland (1963) 373 U.S. 83 [10 L.Ed.2d 215, 83

S.Ct. 1194]. Motion for discovery/prosecution's obligation to provide exculpatory

evidence. Apart from statutory discovery provisions, the Fourteenth Amendment

Due Process Clause imposes on the prosecution an affirmative duty to disclose

Sacramento Superior Court Media Reference Guide

Class Presentation Materials

to the defense, promptly and without request, any obviously exculpatory

evidence possessed by the prosecutor and not readily accessible by the defense.

See Brady, supra, and In re Ferguson (1971) 5 Cal.3d 525, 532.*

“CRUZ WAIVER.” Penal Code section 1192.5 provides that a defendant

who pleads guilty pursuant to a plea bargain which is subsequently disapproved

by the trial court shall be permitted to withdraw the plea if he or she so desires.

The issue before us is whether this provision applies when the trial court

withdraws its approval because the defendant fails to appear for sentencing. *

“DOYLE.” Doyle v. Ohio (1976) 426 U.S. 610 [49 L.Ed.2d 91, 96 S.Ct.

2240]. A Due Process violation for the use of a defendant's silence at the time of

arrest and after receiving Miranda warnings to impeach an affirmative defense

raised at trial. Doyle is not violated by impeachment with post-arrest silence if

defendant testifies that he told police his exculpatory story. “Doyle prohibits the

prosecution from impeaching a defendant’s trial testimony with evidence of the

defendant’s silence after the defendant, having been advised of his constitutional

rights under Miranda v. Arizona chooses to remain silent.” *

“EVANS.” “The broad discretion vested in a trial judge or magistrate

includes the right and responsibility on fairness considerations to deny a motion

for a lineup when that motion is not made timely. Such motion should normally

be made as soon after arrest or arraignment as practicable. We note that

motions which are not made until shortly before trial should, unless good cause is

clearly demonstrated, be denied in most cases by reason of such delay.” Evans

v. Superior Court (1974) 11 Cal.3d 617, 626. *

“FARETTA.” Faretta v. California (1975) 422 U.S. 806 [45 L.Ed.2d 562,

95 S.Ct. 2525]. Defendant has a right to proceed pro per if he knowingly and

intelligently waives the right to counsel. *

“FOSSELMAN/POPE” People v. Fosselman (1983) 33 Cal.3d 572

involves a claim that counsel was ineffective not based upon a withdrawal of a

defense. People v. Pope (1979) 23 Cal.3d 412 involves a claim of ineffective

assistance of counsel based upon a loss of a potentially meritorious defense.

“FRANKS.” Franks v. Delaware (1978) 438 U.S. 154 [57 L.Ed.2d 667, 98

S.Ct. 2674]. Also known as a motion to traverse warrant. “A defendant has a

limited right to challenge the veracity of statements contained in an affidavit

made in support of the issuance of a search warrant (under Franks).” People v.

Lewis and Oliver (2006) 39 Cal.4th 970, 988-989. A motion to “quash” a search

warrant is a related motion based on insufficient showing of probable cause in

the affidavit. In order to prevail on a motion to traverse an affidavit, the

defendant must demonstrate (1) that the affidavit included a false statement

made knowingly and intentionally, or with reckless disregard for the truth, and (2)

Sacramento Superior Court Media Reference Guide

Class Presentation Materials

that the allegedly false statement was necessary to the finding of probable

cause. Franks at pp.155-156; People v. Hobbs (1994) 7 Cal.4th 948, 974. “If the

remaining contents of the affidavit are insufficient to establish probable cause,

the warrant must be voided and any evidence seized pursuant to the warrant

must be suppressed.” People v. Bradford (1997) 15 Cal.4th 1229, 1297 citing

Franks at pp. 155-156. “Moreover, there is a presumption of validity with respect

to the affidavit.” People v. Lewis and Oliver (2006) 39 Cal.4th 970, 989. *

“GRIFFIN.” “Under the Fifth Amendment of the federal Constitution, a

prosecutor is prohibited from commenting directly or indirectly on an accused’s

invocation of the constitutional right to silence. People v. Tafoya (2007) 42 Cal.4th

147, 184, citing Griffin v. California (1965) 380 U.S. 609, 614 [14 L.Ed.2d 106, 85

S.Ct. 1229]. *

“HARVEY-MADDEN.” People v. Harvey (1958) 156 Cal.App.2d 516,

People v. Madden (1970) 2 Cal.3d 1017. See Whitely v. Warden (1971) 401

U.S. 560 [28 L.Ed.2d 306, 91 S.Ct. 1031]. Prosecution must establish the

outside source of information relied on by field officers, after briefing or dispatch,

for detention/arrest. As explained in Sanderson v. Superior Court (1980) 105

Cal.App.3d 264, 268, the Harvey-Whitely rule only applies where “information

relied on to establish probable cause travels from an informant through a relaying

officer to an arresting officer....” *

“HARVEY WAIVER.” People v. Harvey (1979) 25 Cal.3d 754. Imposition

of terms of probation based on dismissed counts based on defendant’s

agreement. “While implicit in ... a plea bargain ... is the understanding ... that

defendant will suffer no adverse sentencing consequences by reason of the facts

underlying, and solely pertaining to, the dismissed count, such adverse

sentencing consequences may properly be imposed if there was agreement to

the contrary. This ‘contrary agreement’ proviso is what has since been called a

Harvey waiver.” People v. Beck (1993) 17 Cal.App.4th 209, 215. *

“HENRY.” The government violates a pre-trial detainee's right to counsel

when it deliberately creates a situation in which a prisoner is questioned by an

informant at the behest of law enforcement in the absence of his counsel. United

States v. Henry (1980) 447 U.S. 264, 274 [65 L.Ed.2d 115, 100 S.Ct. 2183]. See

also Massiah v. United States (1964) 377 U.S. 201, 206 [12 L.Ed.2d 246, 84

S.Ct. 1199] (after release on bail, defendant’s statements to co-defendant who

was cooperating with police and instructed to inquire about the pending charges

violated the Sixth Amendment). Also referred to as Massiah error. *

“KELLETT.” Kellett v. Superior Court (1966) 63 Cal.2d 822. If all

charges from a course of criminal conduct should have been joined, acquittal or

conviction of one (even lesser) charge is a Penal Code §654 bar to further

prosecution. *

Sacramento Superior Court Media Reference Guide

Class Presentation Materials

“PENAL CODE §654” provides that “[a]n act or omission that is

punishable in different ways by different provisions of law shall be punished

under the provision that provides for the longest potential term of imprisonment,

but in no case shall the act or omission be punished under more than one

provision.” Section 654 prohibits multiple punishment for an individual course

of conduct event though it violates more than one statute. People v. Hicks (1993)

6 Cal.4th 784, 789. *

“PENAL CODE § 1118” Penal Code section 1118.1 permits a party to

move for a judgment of acquittal at the close of evidence before the submission

of the case to the jury on the ground that the evidence is insufficient to sustain a

conviction on appeal. *

“PENAL CODE § 1538.5” Penal Code § 1538.5 authorizes a motion to

suppress or a motion to return property in a criminal case. *

“PENAL CODE §995” A motion to set aside an indictment or information

following a preliminary hearing. *

“KELLY-FRYE.” People v. Kelly (1976) 17 Cal.3d 24; Frye v. United

States (DC Cir. 1923) 293 F. 1013. Evidence based on a new scientific

technique is inadmissible until reliability of the scientific method and expertise of

the interpreting witness are established. (Federal courts apply a different test,

see Daubert v. Merrill Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (1993) 509 U.S. 579 [125

L.Ed.2d 469, 113 S.Ct. 2786] (under FRE 702, trial judge has a special obligation

to ensure any and all scientific testimony is not only relevant but reliable).) Kelly

“set forth certain general principles of admissibility of expert testimony based on

new scientific techniques, include the following two step-process: (1) The

reliability of the method must be established by expert testimony, and (2) the

witness furnishing such testimony must be properly qualified as an expert to give

an opinion on the subject. Additionally, (3) the proponent of the evidence must

demonstrate that correct scientific procedures were used in the particular case.”

People v. Leahy (1994) 8 Cal.4th 587, 594. “The Kelly test is intended to forestall

the jury’s uncritical acceptance of scientific evidence or technology that is so

foreign to everyday experience as to be unusually difficult for laypersons to

evaluate.” People v. Venegas (1998) 18 Cal.4th 47, 80. Kelly applies only to a

limited class of expert testimony based on a technique, process or theory which

is new to science. People v. Stoll (1989) 49 Cal.3d 1136, 1156. The distinction

is between expert testimony and scientific evidence, the former is not subject to

the special admissibility rule of Kelly, which applies to cases involving novel

devices or processes. People v. McDonald (1984) 37 Cal.3d 351, 372-373.

California’s state rule is now referred to simply as the Kelly test or rule. People v.

Soto (1999) 21 Cal.4th 512, 515, fn. 3. *

Sacramento Superior Court Media Reference Guide

Class Presentation Materials

“LENT.” People v. Lent (1975) 15 Cal.3d 481. Under Penal Code

§1203.1, the court may impose and require “reasonable conditions” of probation

“specifically for the reformation and rehabilitation of the probationer.” *

“A condition of probation will not be held invalid unless it (1) has no

relationship to the crime of which the offender was convicted, (2) relates to

conduct which is not itself criminal, and (3) requires or forbids conduct which is

not reasonably related to future criminality....” Lent at p. 486. The test is clearly

in the conjunctive, and thus all three factors must all be found to be present in

order to invalidate a condition of probation. People v. Balestra (1999) 76

Cal.App.4th 57, 65, fn. 3. But there is no nexus requirement for a probation

search condition. It may be imposed even if it has no “relationship to the crime of

which the offenders was convicted” (Lent at p. 486), even if the underlying

offense is not theft-related. People v. Brewer (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 1298, 1311.

In addition to Lent’s three part test, constitutional safeguards circumscribe the

court’s discretion in imposing probation conditions. People v. Hodgkin (1987) 194

Cal.App.3d 795, 802; People v. Pointer (1984) 151 Cal.App.3d 1128, 1137.

“MARSDEN.” People v. Marsden (1970) 2 Cal.3d 118. See People v.

Stephens (19848) 156 Cal.App.3d 1119. Defendant's request to

discharge/substitute counsel for incompetent defense requires in-camera hearing

(prosecutor excluded). “A defendant is entitled to substitute another appointed

attorney if the record clearly shows that the first appointed attorney is not

providing adequate representation or that defendant and counsel have become

embroiled in such an irreconcilable conflict that ineffective representation is likely

to result.” People v Valdez (2004) 32 Cal.4th 73, 95, citing People v. Welch

(1999) 20 Cal.4th 701, 728. *

“MURGIA.” Murgia v. Municipal Court (1975) 15 Cal.3d 286. See People

v. Superior Court (Hartway) (1977) 19 Cal.3d 338. Motion to dismiss for lack of

equal protection, alleging the defendant was singled out for prosecution only

because of invidious discrimination. “Although referred to for convenience as a

‘defense,’ a defendant's claim of discriminatory prosecution goes not to the

nature of the charged offense, but to a defect of constitutional dimension in the

initiation of the prosecution.” *

“PITCHESS.” Pitchess v. Superior Court (1974) 11 Cal.3d 531. See PC

§§ 832.5, 832.7, 832.8; Evidence Code §§1043-1047. Defense motion to

discover records of complaints in police personnel files to support a self-defense

claim, usually in §§148/243 cases or in allegations of a coerced confession.

Peace officer personnel records are confidential and shall not be disclosed

except by discovery pursuit to EC §§1043 and 1045. *

“SERNA.” Serna v. Superior Court (1985) 40 Cal.3d 239. Motion to

dismiss for lack of speedy trial where delay between accusation and arrest

exceeded statute of limitations period for a misdemeanor. *

Sacramento Superior Court Media Reference Guide

Class Presentation Materials

“TROMBETTA.” California v. Trombetta (1984) 467 U.S. 479 (81 L.Ed.2d

413, 104 S.Ct. 2528). If the state deliberately destroys material defense

evidence, the prosecution may be limited in offering the people's version of the

evidence (test results, etc.). “Law enforcement agencies have a duty under the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, to preserve evidence that

might be expected to play a significant role in the suspect’s defense. To fall

within the scope of this duty, the evidence must both possess an exculpatory

value that was apparent before the evidence was destroyed, and be of such a

nature that the defendant would be unable to obtain comparable evidence by

other reasonable available means. The state’s responsibility is further limited

when the defendant’s challenge is to the failure of the State to preserve

evidentiary material of which no more can be said than that it could have been

subjected to tests, the results of which might have exonerated the defendant. In

such case, unless a criminal defendant can show bad faith on the part of the

police, failure to preserve potentially useful evidence does not constitute a denial

of due process of law.” People v. Catlin (2001) 26 Cal.4th 81, 159-160 (citations

to Trombetta, Youngblood, Roybal and Beeler); see also People v. Carter (II)

(2005) 36 Cal.4th 1215, 1246. California initially had a stricter rule for such

destruction (People v. Hitch (1974) 12 Cal.3d 641), which it has since

abandoned. People v. Cooper (1991) 53 Cal.3d 771, 810; People v. Johnson

(1989) 47 Cal.3d 1194, 1233-1234. *

“WHEELER.” People v. Wheeler (1978) 22 Cal.3d 258. Motion to quash

a jury venire and repeat jury selection, alleging a discriminatory exercise of

peremptory challenges to exclude members of a cognizable group on a biased

basis. “Both the state and federal Constitutions prohibit the use of peremptory

challenges to exclude prospective jurors based on race or gender. Such a use of

peremptories by the prosecution ‘violates the right of a criminal defendant to trial

by a jury drawn from a representative cross-section of the community under [both

the state and federal Constitutions].’” *

“MOTION TO REDUCE CHARGES (Penal Code §17(b)). Commonly

known as a “17(b)” motion. This provision invests the trial court with discretion to

treat a felony punishable … by imprisonment in the state prison or by fine or

imprisonment in the county jail as a misdemeanor. These offenses, which can

be sentenced either in state prison or county jail (commonly as a term of

probation), are known as “wobblers.” Offenses which state only imprisonment as

the punishment are referred to as “straight felonies.” (See People v. Mendez

(1991) 234 Cal.App.3d 1773, 1779 fn. 5.) *

Sacramento Superior Court Media Reference Guide

Class Presentation Materials

You might also like

- Evidence Outline Goodno (Spring 2013) : Exam: We Do NOT Need To Know Rule Numbers or Case Names I.PDocument36 pagesEvidence Outline Goodno (Spring 2013) : Exam: We Do NOT Need To Know Rule Numbers or Case Names I.PzeebrooklynNo ratings yet

- Employment Discrimination 2012Document44 pagesEmployment Discrimination 2012Mal Durham-BowmansNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Brief/Notes 9-6 Federal Question JurisdictionDocument4 pagesCivil Procedure Brief/Notes 9-6 Federal Question JurisdictionRebecca LopesNo ratings yet

- Winker's Motion For SanctionsDocument6 pagesWinker's Motion For Sanctionsal_crespoNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide by Michael Cetewayo Tabor RIUDocument21 pagesCapitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide by Michael Cetewayo Tabor RIUDerrick MatthewsNo ratings yet

- Exam Pointers PrelimDocument29 pagesExam Pointers PrelimMa. Ana Joaquina SahagunNo ratings yet

- End of America Sample PagesDocument40 pagesEnd of America Sample PagesChelsea Green Publishing100% (2)

- 1203 4 Dismissal Process 1Document12 pages1203 4 Dismissal Process 1T RodNo ratings yet

- Brief of AppelleeDocument48 pagesBrief of AppelleeSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- PATRICK S. HALLINAN (#33838) KENNETH H. WINE (#142385) Hallinan & Boro 703 Market Street, 8th Floor San Francisco, California 94103 (415) 536-4111Document30 pagesPATRICK S. HALLINAN (#33838) KENNETH H. WINE (#142385) Hallinan & Boro 703 Market Street, 8th Floor San Francisco, California 94103 (415) 536-4111kenwineNo ratings yet

- Hurley Motion SupressDocument16 pagesHurley Motion SupressHayden SmithNo ratings yet

- Daewoo's Motion to Exclude Evidence of Presumed KnowledgeDocument6 pagesDaewoo's Motion to Exclude Evidence of Presumed KnowledgeBabak EeroonyNo ratings yet

- Evidence Functions of Judge, Jury and Attorneys at Trial: OutlineDocument39 pagesEvidence Functions of Judge, Jury and Attorneys at Trial: OutlineKarandeep Singh PawarNo ratings yet

- INCRUISES Terms of Service-ENDocument12 pagesINCRUISES Terms of Service-ENriyaz9999100% (1)

- Evidence Questions For FinalDocument5 pagesEvidence Questions For FinalNaderNo ratings yet

- NDU Civ Pro OutlineDocument29 pagesNDU Civ Pro Outlinelaw1981No ratings yet

- Motion To "Prohibit Testimony of Alleged Prior Bad Acts"Document2 pagesMotion To "Prohibit Testimony of Alleged Prior Bad Acts"ActionNewsJaxNo ratings yet

- Hoffa v. United States, 387 U.S. 231 (1967)Document3 pagesHoffa v. United States, 387 U.S. 231 (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- FRCP PDFDocument176 pagesFRCP PDFKat-Jean FisherNo ratings yet

- Motion For Protective OrderDocument5 pagesMotion For Protective OrderJournal Star100% (1)

- CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM - Q&A - ReviewNotesDocument19 pagesCRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM - Q&A - ReviewNotesEarl Jann LaurencioNo ratings yet

- NLRB Denies Leslie Smith Appeal LetterDocument13 pagesNLRB Denies Leslie Smith Appeal LetterMMA PayoutNo ratings yet

- LEGAL STUDIES EXAM PREPDocument5 pagesLEGAL STUDIES EXAM PREPThakshana VigneswaranNo ratings yet

- DCEB 13 616 Appellate BriefDocument19 pagesDCEB 13 616 Appellate BriefMark R.No ratings yet

- National Archives Appellee BriefDocument48 pagesNational Archives Appellee BriefStephen Loiaconi100% (1)

- 131 Master Omnibus and JoinderDocument172 pages131 Master Omnibus and JoinderCole StuartNo ratings yet

- 2019-06-13 Wroth vs. City of Rohnert Park - Volume 8-Pages-40-122Document83 pages2019-06-13 Wroth vs. City of Rohnert Park - Volume 8-Pages-40-122Izaak SchwaigerNo ratings yet

- General Denial and 16 Defenses to ComplaintDocument7 pagesGeneral Denial and 16 Defenses to Complaintjverga100% (1)

- Citigroup's Motion To Dismiss Terra Firma's EMI LawsuitDocument31 pagesCitigroup's Motion To Dismiss Terra Firma's EMI LawsuitDealBookNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Structural OutlineDocument19 pagesCivil Procedure Structural OutlineSaulNo ratings yet

- 3176 Qa CriminalDocument40 pages3176 Qa CriminalMagazine BoxNo ratings yet

- Allen Feingold v. Liberty Mutual Group, 3rd Cir. (2014)Document7 pagesAllen Feingold v. Liberty Mutual Group, 3rd Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Revisting Evidence Binder PDFDocument105 pagesRevisting Evidence Binder PDFRaven BennettNo ratings yet

- Appellate Motion Brief (Writing Sample)Document15 pagesAppellate Motion Brief (Writing Sample)shausoon100% (1)

- Basic DecencyDocument44 pagesBasic DecencySC4YNo ratings yet

- Lockwood Complaint & Jury DemandDocument12 pagesLockwood Complaint & Jury DemandMark KlekasNo ratings yet

- 065 Verizon Motion To Quash Motion For Protective Order SharpDocument11 pages065 Verizon Motion To Quash Motion For Protective Order SharpJ DoeNo ratings yet

- Admissible:Inadmissible Character EvidenceDocument7 pagesAdmissible:Inadmissible Character Evidencemdean10No ratings yet

- William Darby Motion For New TrialDocument7 pagesWilliam Darby Motion For New TrialmNo ratings yet

- 20 08 12 Petition For ContemptDocument39 pages20 08 12 Petition For ContemptDanny ShapiroNo ratings yet

- Appellate Practice in Nebraska - CRLR 29Document55 pagesAppellate Practice in Nebraska - CRLR 29mmehnerNo ratings yet

- Baciredo, William - Notice of Hearing - Case #08-057678 CA 21Document2 pagesBaciredo, William - Notice of Hearing - Case #08-057678 CA 21brokawNo ratings yet

- 12:78 Motion To Exclude Evidence Not Contained in TheDocument4 pages12:78 Motion To Exclude Evidence Not Contained in ThejusticefornyefrankNo ratings yet

- Justice Act (Just and Unifying Solutions To Invigorate Communities Everywhere)Document15 pagesJustice Act (Just and Unifying Solutions To Invigorate Communities Everywhere)acohnthehillNo ratings yet

- SAMPLE Exam Evidence NEW 2019 PDFDocument19 pagesSAMPLE Exam Evidence NEW 2019 PDFS.k.raghavNo ratings yet

- DefensesDocument1 pageDefensesjNo ratings yet

- Evidence Rules and Relevance in Criminal CasesDocument58 pagesEvidence Rules and Relevance in Criminal CasesRob BiggersNo ratings yet

- LLT Forms TocDocument5 pagesLLT Forms TocRONINM3No ratings yet

- Defense Motion On Jury Instructions at Nikolas Cruz Battery TrialDocument4 pagesDefense Motion On Jury Instructions at Nikolas Cruz Battery TrialDavid SeligNo ratings yet

- Proving Gang Offenses and EnhancementsDocument13 pagesProving Gang Offenses and EnhancementsGil VasquezNo ratings yet

- FBI Motion For Protective OrderDocument5 pagesFBI Motion For Protective OrderThe Dallas Morning NewsNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Outline 1 1. Personal JursidicitionDocument38 pagesCivil Procedure Outline 1 1. Personal JursidicitionunkellsamNo ratings yet

- Disc 001Document8 pagesDisc 001marlanelaurenNo ratings yet

- Washington Police Departments Surplus ListDocument16 pagesWashington Police Departments Surplus ListErin RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Texas Law On Piercing Corporate VeilDocument9 pagesTexas Law On Piercing Corporate VeilJim HarlanNo ratings yet

- Federalism Values Rarely Discussed in Supreme Court CasesDocument42 pagesFederalism Values Rarely Discussed in Supreme Court CasesGustavo LiberatoNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure II OutlineDocument20 pagesCivil Procedure II Outlinestarfish_carouselNo ratings yet

- Born This Way Drug Test DisputeDocument10 pagesBorn This Way Drug Test DisputeJames BondNo ratings yet

- Mock Trial SamplesDocument2 pagesMock Trial Samplesapi-448269753No ratings yet

- United States v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984)Document70 pagesUnited States v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Business Associations Rule Statements (2020)Document4 pagesBusiness Associations Rule Statements (2020)N.A.No ratings yet

- 666 Suit ComplaintDocument12 pages666 Suit ComplaintSiouxsie LawNo ratings yet

- Intentional Torts OutlineDocument6 pagesIntentional Torts OutlinefeliciaNo ratings yet

- MotionsDocument6 pagesMotionsT RodNo ratings yet

- Unemployment Benefit Programs: Start Here!Document1 pageUnemployment Benefit Programs: Start Here!Omsare ResNo ratings yet

- Correspondence TemplateDocument1 pageCorrespondence TemplateT RodNo ratings yet

- Letter PMSanchez COVID19 Catalan Prisoners MEPS PDFDocument2 pagesLetter PMSanchez COVID19 Catalan Prisoners MEPS PDFPúblico DiarioNo ratings yet

- Cor-Ad Q&aDocument40 pagesCor-Ad Q&aReen DousNo ratings yet

- Testimony of Boris LuiDocument2 pagesTestimony of Boris LuiAlpha Hong KongNo ratings yet

- 7 People V TemporadaDocument152 pages7 People V TemporadaFrench TemplonuevoNo ratings yet

- English MidDocument3 pagesEnglish Midsamuel asefaNo ratings yet

- People V JalosjosDocument1 pagePeople V JalosjosA M I R ANo ratings yet

- CRPC Ica IvDocument10 pagesCRPC Ica IvTanay BothraNo ratings yet

- Georgia Department of Corrections - EVERETT JEROME TRIPODIS, GDC ID: 1000925170Document2 pagesGeorgia Department of Corrections - EVERETT JEROME TRIPODIS, GDC ID: 1000925170TVFishbowlNo ratings yet

- Shantanu Agnihotri (R) Criminology ParoleDocument15 pagesShantanu Agnihotri (R) Criminology ParoleShantanu AgnihotriNo ratings yet

- The Advantages of The Legalization of Death Penalty All Around The World.Document6 pagesThe Advantages of The Legalization of Death Penalty All Around The World.Manaf MahmudNo ratings yet

- A Life of Struggle: InsideDocument2 pagesA Life of Struggle: InsideGuisellaNo ratings yet

- Week 10 Case Corrections Study, CRJ100, Strayer UniversityDocument4 pagesWeek 10 Case Corrections Study, CRJ100, Strayer UniversityTerry MwendwaNo ratings yet

- The Maze Runner Work Sheet CH11-15Document3 pagesThe Maze Runner Work Sheet CH11-15Ali QudahNo ratings yet

- (2020) CLJ JT (1) - RevisionDocument10 pages(2020) CLJ JT (1) - Revisionesteban jufriNo ratings yet

- Gcso Law Enforcement Summary: Media Release June 2, 2020Document3 pagesGcso Law Enforcement Summary: Media Release June 2, 2020Michael AllenNo ratings yet

- Health Status and Needs of Incarcerated WomenDocument2 pagesHealth Status and Needs of Incarcerated WomenVANESSA MARIE VERDEFLORNo ratings yet

- Mysterio's illusions and battles against Spider-ManDocument1 pageMysterio's illusions and battles against Spider-ManAaditya JoshiNo ratings yet

- Notes On Correctional Administration Correctional Administration 1 and Correctional Administration 2Document108 pagesNotes On Correctional Administration Correctional Administration 1 and Correctional Administration 2Maria SisonNo ratings yet

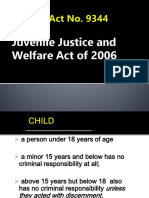

- Republic Act No. 9344Document47 pagesRepublic Act No. 9344Nur SanaaniNo ratings yet

- Fifth Circuit Opinion in Ellis Ray Hicks v. Department of Public Safety & CorrectionsDocument11 pagesFifth Circuit Opinion in Ellis Ray Hicks v. Department of Public Safety & CorrectionsWilliam MostNo ratings yet

- Personality disorders and hostage negotiation strategiesDocument4 pagesPersonality disorders and hostage negotiation strategiesJvnRodz P GmlmNo ratings yet

- Custodial Death ExplainedDocument14 pagesCustodial Death ExplainedMAHFUZ ISLAMNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesLesson PlanNozima ToirovaNo ratings yet

- Michael Kanaan (Born 23 May 1975)Document6 pagesMichael Kanaan (Born 23 May 1975)Alfred Mujah JimmyNo ratings yet

- Shahrukh JatoiDocument11 pagesShahrukh JatoiKanza JamilNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Unit 1 Test TeacherDocument15 pagesGrade 11 Unit 1 Test Teacher2np8xcsc26No ratings yet

- ExtrasDocument8 pagesExtrasnabeelNo ratings yet