Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 89.164.29.222 On Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

Uploaded by

Ljuban SmiljanićOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 89.164.29.222 On Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

Uploaded by

Ljuban SmiljanićCopyright:

Available Formats

The Diffusion of the Writings of Petrus Ramus in Central Europe, c. 1570-c.

1630

Author(s): Joseph S. Freedman

Source: Renaissance Quarterly , Spring, 1993, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 98-152

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of

America

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3039149

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Renaissance Society of America and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR

to digitize, preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Diffusion of the Writings of Petrus Ramus

in Central Europe, c. 1570-c. 1630

by JOSEPH S. FREEDMAN*

FOR WHAT REASONS DID ACADEMICIANS select to use or not to use

any given textbook for their own classroom instruction during

the Renaissance? To what extent did ideological or pragmatic con-

siderations influence such decisions? In this article these questions

are posed to examine the use of the writings of Petrus Ramus (I 5I 5-

1572) and Omer Talon (ca. 15IO--1562) at schools and universities

in Central Europe during the six decades between I570 and 1630.

Did "Ramist" academicians of this period make use in the class-

room of writings by these two authors because of some fundamen-

tal agreement with their views? Or were these two authors pre-

ferred during these six decades because their writings could be used

eclectically and/or they fit well into specific parts of the curriculum

at certain academic institutions?

In the period between I570 and 1630 there were over 30 univer

sities and hundreds of schools in the German-language area of Eu

rope.I A large amount of curricular information-largely in the

form of annual, semi-annual, or occasional outlines of instructio

as well as personal or official correspondence-exists for many o

these schools and universities. Textbooks and printed disputation

arising from instruction held at these academic institutions are also

extant. This assessment of the use of writings by Ramus and Talon

in Central European academic institutions is based on the exam

nation of a substantial portion of this evidence. The task of finding

and evaluating such evidence pertaining to other parts of Europ

must be left for a separate study.

One of the most influential monographs on Petrus Ramus, titled

Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue, was published by Walter

*This article is an expanded and amended version of a paper read at the Sevent

Meeting of the International Association for Neo-Latin Studies in Toronto on I2 A

gust 1988. Library and archive locations (together with call numbers) are given for a

source materials cited within this article. Refer to the abbreviations given at the begin

ning of the bibliography.

IThe best annotated bibliography of these schools and universities in Central Eu

rope is Goldmann.

[98]

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS 99

Ong in 1958.2 The significance of this monogra

hanced by his publication that year of a bibliograph

of the writings of Ramus and Talon, his Ramus and

which encompasses editions published both durin

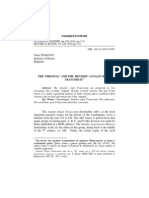

lifetimes.3 Table A originally appeared within O

but was constructed on the basis of data given w

liography.4

Table A provides valuable information concerning the chrono-

logical and geographical dimensions of the proliferation of writings

by Petrus Ramus and Omer Talon. Using it, we can present the fol-

lowing three hypotheses: i. Central Europe (which for the pur-

poses of this paper shall be equated with the German-language area

of Europe, including Germany, German Switzerland, and Alsace)

is the area in which the writings of Ramus and Talon on logic and

rhetoric were most extensively used. 2. The extensive use of these

writings in Central Europe is basically limited to the years between

1570 and 1630. 3. Based on the places of publication given here in

Table A it can be postulated that these writings on logic and rhetoric

were much less extensively used at universities than at other kinds

of academic institutions. Additional printed and manuscript

sources found while researching this paper have served to give fur-

ther credence to these three hypotheses, each of which will be re-

turned to later.

First, however, it is imperative to discuss the use of terms such

as "Ramist," "Semi-Ramist," and "Philippo-Ramist." This kind

of terminology is sometimes used in order to explain the spread of

writings by Ramus and Talon on logic, rhetoric, and other subjects.

I would like to suggest that the use of such terminology is prob-

lematic when applied to Central Europe in the period between 1570

2Ong, I9581. A recent monograph by Philip Leith also makes substantial use of

Ong's work on Ramus. Leith argues that the rapid rise and subsequent decline in the

popularity of Ramus's writings was due to the massive yet unsuccessful attempt of

those writings to arrive at a complete formalization of thought; see Leith, 37, 73-9I.

There is an abundance of additional recent literature on Petrus Ramus; the following

two articles present excellent summaries of that literature: Sharratt, 1987, and Sharratt,

1972.

30ng, I9582.

40ng, I958I, 296. This table has been reproduced here with the permission of Har-

vard University Press (#881391).

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ioo RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLE A. The Spread of the Writings

Petrus Ramus as Tabulated by W

DISTRIBUTION OF EDITIONS (INCLUDING ADAPTATIONS)

OF THE RAMIST DIALECTIC AND RHETORIC (FIGURE XV)a

Based on Ong, Ramus and Talon Inventory

Year FRANCE SPAIN GERMANY SWITZER- BRITISH ALSACE LOW ALL TOTALS

(EXCLU- LAND ISLES COUN- ELSE

SIVE OF Sala- Frankfort/M Stras- TRIES Phila-

ALSACE) manca Cologne Basle London bourg delphia

Marburg (Lahn) Zurich Cam- Mul- Leyden New

Paris Herborn Bern bridge house Amsterdam York

Lyons Hanau Geneva Oxford Utrecht

La Rochelle Dortmund Edin- Middelburg

Niort Nuremberg burgh (English

Sedan Speyer Puritan

Siegen colony)

Lemgo The

Magdeburg Hague

Bremen Tiel

Brunswick

Erfurt

Giessen

Hamburg

Hanover

Jena

Leipzig

Lich

Lubeck

Rostock

Stuttgart

Coburg

Goslar

Oppenheim

Rinteln

Ursel

Wittenberg

Di Rh Di Rh Di Rh Di Rh Di Rh Di Rh Di Rh Di Rh Di Rh

I543 (5 I) (I I)

-I557 (12A) (4 I)

I55 8 2 2 2 14

-I572 20 2 3 I 26

1573 5 I 14 (I I) 2 3 25

-1580 6 I 4 (2A) I 12

I58I I 34(2A) 7 II I 5 59

-1590 I I 12 5 I 3 23

I591 49(IA) 2 I 52

-600o I 15 I 4 I 22

I60I 20 2 22

-i6io 13 4 I 18

1611 16 4 I I I 23

-1620 I 8 I I I 12

1621 9 2 II

-1630 7 3 I0

1631 2 5 I I 9

-1640 I 5 4

1641 I I I 6 9

-650 I I 4 2 8

65 I 2 3 5 10

-I660 I 6 I 8

1661 3 2 6 4 15

-1700 4 I 5 I II

1701 2 2 (I I) 4

-I8oo I 2 2 (I A) I 6

i8oi 7 2 9

-1950 2 2 4

Total 14 4 151 23 42 4 22 2 262

Total 31 4 69 i6 33 0 II 2 166

Figures in parentheses, no

and Rhetoric grew: (I) Dial

aUnder each country, mun

preceding the less. 1572 i

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS ioI

and I630. While relevant Central European te

use these terms, they do not do so in a way whic

or precise.

Here we shall look at three different kinds of primary sources in

order to evaluate the meaning of this terminology. First, we will

examine how individual works titled as "Ramist," "Philippo-

Ramist," and the like, discuss the following two points of philo-

sophical doctrine: the classification of philosophical disciplines and

the concept of method. Second, we shall see how the writings of

Ramus and Ramus's followers are used in the works of one philos-

opher. And finally, we shall look at the titles of 2I printed works

which pertain to Ramus with respect to the actual content of these

works. Each of these three kinds of sources will be examined here

in turn.

Seven different classifications of philosophical disciplines are

presented in Tables B, C, D, E, F, G, and H.5 The classification

given in Table B is byJohannes Thomas Freigius (1543-I583), one

of Ramus's most avid disciples.6 Table C is taken from a "Philippo-

Ramist" general textbook on the liberal arts.7 Tables E and F are

classifications given by unnamed followers of Ramus as presented

byJoannes Henricus Alstedius (1588-163 8) in 1612.8 Tables D, G,

and H are taken from commentaries on Ramus's logic by Rudolph

Goclenius the Elder (1547-I628), Severinus Sluterus, and Antho-

nius Peitmann.9

5Some of these, as well as some other classifications of philosophical disciplines, are

presented and discussed in the following publications: Freedman, I9852; Freedman,

1985', 65-72.

6Freigius, 579, A6v. The following works provide biographical and bibliograph-

ical information concerning Freigius: Ong, I958I, 399; Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie,

7: 34I-43.

7Bilstenius, I-2.

8"Technologia Rameorum. Plures Peripateticorum sententias de partitione

phia colligant sibi studiosi. Nos nunc colligemus summatim quae Ramei p

habent de partitione philosophiae. Petrus Ramus, quod sciam, in scriptis su

philosophiae ideam & partitionem generalem nobis reliquit. Sed discipuli &

ejus, ex scriptis, quae edidit, sequentem philosophiae distributionem extruun

dius, 1612, 373-74. Such a classification authored by Petrus Ramus himself

be located when researching this article. Concerning the life and writings of

Heinrich Alsted see Theologische Realenzyklopadie, 2: 299-303.

9Goclenius, 600o, I05; the title of this work by Goclenius is cited more fu

of Table M; Sluterus, 1612, table following 54; Peitmann, 4I-64. Peitmann

fessor of logic at the University of Rinteln; this is evident from the title pa

he is referred to as Logicae profess. publicus) and from the preface (espec

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I02 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLES B-H. Seven "Ramist" Classifications

of Philosophical Disciplines

TABLE B. Johannes Thomas Freigius (1576)

puram= Grammatica

((orationem): t solutam = Rhetorica

I ornatam

instrumenta l a

(rationem): Logica (su

(Arithmetica

Philosophia quantitatem = Mathematica

Geometria

naturam rerum Musica

(rerum hoc Optica

est

p s circa): Astroqualitatem

est circa):

^partes^ Physiologia

Oeconomia

Oeconomua 11

Psychologia

. Meteo

mores = Ethica

Politica

On the basis of these seven classifications the following two

points can be made here. First, each classification is quite distinct

from the next. It is difficult to say which one is more or less

"Ramist, " particularly since all of the works in which they appear

are "Ramist" in some manner. Neither Ramus nor Talon ever seem

to have produced such a classification of the philosophical disci-

plines. I

Such individual differences can be seen by looking at these seven

classifications. Philosophy is referred to as philosophia in Tables B,

D, E, F, G, and H, as artes liberales in C and as ars philosophica in

H. Philosophy includes logic, rhetoric, and grammar in all of these

classifications except for the one in Table D. Tables B, C, D, and

Concerning the life and writings of Rudolph Goclenius the Elder, see Allgemeine Deut-

sche Biographie, 9: 308-12; Strieder, 4: 428-87; his life, writings, and influence are dis-

cussed in Freedman, I9881, 92-93, 524 (and those pages referred to in the index).

I°See the passage cited in footnote 8; modern scholarship on Ramus has not pro-

duced any evidence to the contrary.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS I03

TABLE C. Joannes Bilstenius (I588)

C Trammatica

p Ihetorica

exotericae

'oetica

(schlechte

)ialectica

Kiinste) L

Optica

Astronomia

Physica < Geographia

artes liberales 4 Medicina

Musica

Arithmetica

acroamaticae

Mathematica r Geomet ria

(hohe

Kiinste) Architec

tura

Politica

Oeconomica

Apodemica

Ethica Polemica

Historia

Jurisprudentia

Theologia

TABLE D. Rodophus Goclenius (I600)

metaphysica

res necessanae

physica -- astronomia; sphaerica

(theoreticae) arithmetica - musica

mathematica

diartes philosophiae ethica geometria . - optica

discipnae J res contingentiae oeconomica

scliberales (practicae) politica

huius instber a maca, rhetorica, logica

huius instrumenta: grammatica, rhetorica, logica

E all give diverse representations of the contents of physics while

Tables B, C, D, E, F, and G all have divergent classifications of

mathematical disciplines. The sub-categories of ethics given in Ta-

ble B are not same as the sub-categories given in Table C. No sub-

categories of ethics are given in Tables D, E, F, G, and H.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I04 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLES E-F. Classifications Given by Two Followers of R

According to Johannes-Henricus Alstedius (1612)

ratione = dialectica

[generalis i

(geoerati grammatica

oratione

rhetorica

philosophia de quantitate multa = arithmetica

quantitatis

E. philosophia

(= mathematica) de qualitate magna = geometria

philosophia

cognitionis osophia prima = physica

philosophia )

qualitatis Astronomia

qualitatis a prima orta Musica

Optica

specialis

ars obsequendi = ethica

(publica . oeconomica

osophia ars imperandi . .politica

philosophia polmtca

actionis

agens = agricultura

privata

faciens = architectonica

dialectica

artes logicae rhetorica

grammauca

propaidia (= instrumentum philosophiae) gramat

J fI I ~arithmetica

F.

F. phiosophia artes mathematicae geometria

phlosophmetria

paideia ( = philosophia) physic

ethica with the use

Secondly, Tables B, C, D,

the period between 1575 an

tance of the discipline of m

tion of Freigius in 1576, met

of logic. The classifications

1612 make metaphysics an

By 1626 the classification g

make metaphysics the most

we shall see later, this deve

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS I05

TABLE G. Severinus Sluterus (1612)

dialectica

Instrumentalis rhetorica - oratoria

grammatica - poetica

generalis /

Realis, ut Metaphysica

fphysica fm

~,4~h,hm;,-r I

Philosophia

verum

mathemadca cosmologia

geographia

specialis geodasia

I

stereometria

astronomia

genere = ethica optica

bonum

specie politica

oeconomica

TABLE H. Anthonius Peitmann (1626)

1. philosophia

subordinata logica, grammatica, rhetorica, physica, medica, musica,

et ] architectonica, mechanica, optica, ethica, oeconomica, politica,

secunda Ljuridica, apodemica, polemica, historica, chronologica

rationis = dialectica

generalis (prima philosophica lexicon

oradonis grammatica &

rhetorica philologia

2. ars philosophia

I naturans = theosophia

naturae = theoreticanaturans theosophia

specialis . naturata (= physica/mathematica?)

morum = practica

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Io6 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

changing attitudes toward the use of Ramus's writings in

European schools during the early seventeenth century.

The concept of method was discussed frequently in

sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Central Europe

nection with Petrus Ramus. Neal Ward Gilbert has noted that this

concept begins to be discussed shortly before I550 in writings o

logic as well as works written specifically on method itself.

Gilbert also makes the observation that various terms such as via

("way"), ratio ("reason"), modus ("manner"), and methodus

("method") are used in sixteenth-century sources in order to ref

to method.12 Eight examples of late sixteenth- and ear

seventeenth-century works by Central European authors whic

discuss or at least mention method are presented in Table I.I3

these eight examples the terms via, ratio, ratiocinatio ("reasoning")

modus, ordo ("order"), or some combination thereof are used wh

reference is made to "method."

These examples highlight the problem of assigning an exact

meaning to the term "method" in late sixteenth- and ear

seventeenth-century texts.I4 This complicates any attempt to u

derstand how the term "method" is utilized in writings on lo

where Petrus Ramus is mentioned. An additional complication

posed by the fact-as Walter Ong, Cesare Vasoli, and Nelly

Bruyere have shown-that Ramus's own views on method did n

remain the same during his entire academic career.I5

IGilbert, 121-22. The earliest such discussion which I have used to date is that pu

lished by Erasmus Sarcerius in the year 1539: Sarcerius, A2-A8. However, the te

methodus (methadus) appears to have had at least some currency at the beginning of

sixteenth century; see Hundt, cIv. The extent to which terms such as methodus, mod

ratio, and via were used in medieval philosophical writings has yet to be determine

I2Gilbert, 68-69, I76-77.

I3In addition, see the disputations on method presided over byJohann Heinrich

sted, Heinrich Dauber, and Heinrich Gutberleth which are referred to in footnote

below and cited in the bibliography.

I4Willich, I; "Methodus, est via docendi certa cum ratione, hoc est, methodus

ratio docendi .. ." Hemmingius, I565, 3; Ursus, 2; Sallerus and Thoveninus, I5

2; Beurerus, I; Neldelius, 2-3; Coelius, 98-IOI; "Methodus autem vel ordo (n

parum inter hac vel nihil discriminis) est ad adiscendum, docendum, verumq; inveni

dum apta rerum cognitarum dispositio." Brunnemannus, 423.

I In addition, it should be noted that sixteenth- and seventeenth-century authors

not attempt to find exact definitions of terms in the manner of many of their twenti

century counterparts. Definition theory was a part of the discipline of logic during

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; real definition, nominal definition, descriptio

imperfect definition, and essential definition are among the sub-categories of defini

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS I07

TABLE I. Terminology Used to Define and/or

Method Within Select Sixteenth- and Early Seven

Texts on Logic

i. Jodocus Willichius/De methodo omnium artium et disciplinarum/

I550; 2. Nicolaus Hemmingius/De methodis libri duo/I565; 3. Nico-

laus Raymarus Ursus/Metapmorphosis logicae/ I589; 4. Ioannes

Sallerus S.J. /Disputatio logica De methodo/I592; 5. Ioannes Iacobus

Beurerus/Methodice [Gr.]: sive de usu organi logici/I597; 6. Johannes

Neldelius / Pratum logicum Organi Aristotelici/I607; 7. Michael

Coelius / Prodromus philosophiae Peripateticae/ I626; 8. Iohannes

Brunnemannus / Enchiridion logicum ex Aristotele et Philippo / 639

I. Methodus est . . . via atque ratio vel est . . . modus

2. Methodus est via docendi . . .hoc est ... ratio docendi

3. Methodus est ratiocinatio . . .

4. (methodus): is described in terms of dispositio and modus

roughly equivalent to ordo

5. Methodice est doctrinarum, consiliorum de ratione, & ordi

comprehensio.

6. Methodus [=] . . . ordo doctrinae . . . modus probandi .

7. Coelius supplements the term methodus with modus, via,

ratio.

8. Methodus est ... ordo . . . dispositio.

TableJ presents in summary form views on methods given

different writings that mention Ramus. Numbers I, 2, a

commentaries on Ramus's logic. Number I presents what

tially a view found in Ramus's own logic. I6 It appears to hav

a matter of principle for many authors that they shou

method exactly as it was presented in one or more texts by

himself.17 This was to some extent a polemical issue in

Europe during the decades around I600.i8 However, num

and 3 depart to some extent from Ramus's views on me

that were used in that period. For example, see the following presentations

categories of definition: Crucius, B5v-B7; Wedemannus, table 8 (A4v), t

'6Ong, I958', 245-54, 402; Vasoli, 568-6oi; Bruyere, 41-202.

'7Beurhusius, 1583, 733-35.

'8The authors of the three disputations cited in footnote 28 apparently in

do precisely that.

I9Bartholomew Keckermann's discussion of Ramus's method is one indication of

this; see d.6 in number 2 of Table N as well as footnote 71 below.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Io8 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLE J. Discussions of Method (methodus) within Ten

on Logic in which Petrus Ramus is Mentioned

i. Fredericus Beurhusius / Ad P. Rami Dialecticam/I583; 2. Dav

Schramus/Partitiones logicae et rhetoricae, ad verae methodi R

leges/ I 589; 3. Conradus Neander/Tabulae... in ... illam diss

artem. P. Rami Dialecticae/159I; 4. Rupertus Erytropilus / Tab

generales in Dialecticam P. Rami, quibus ex altera facie opponu

tabulae ex praeceptis Dn. Philippi Melanchthonis/ 588; 5. Paulu

Frisius/Comparationum dialecticarum ... quibus Philippi Melan

thonis, & Petri Rami praecepta dialectica ... conferuntur/I59o;

Otho Casmannus/Logicae Rameae & Melanchthonianae collat

Exegesis/ 1594; 7. Bartholomaeus Sengebehr/Compendium dial

Philippi ... item P. Rami observationibus utilissimis illustrata/

8. Gregor Horstius/Institutionum logicarum, libri duo ... ex A

tele, eiusdemque interpretibus / I608; 9. Andreas Cramerus /

Comparationum logicarum . . . dialecticae Philippeae/ I6Io; IO.

ens Timplerus / Logicae systema methodicum/I6I 2.

I. Beurhusius says that methodus est dianoia variorum axiom

homogeneorum pro naturae suae claritate prarepositorum, u

omnium inter se convenientia iudicatur memoriaque compre

tur. This method consists of "sola & unica" via i.e.:

a. ab antecedentibus notioribus -> consequentia ignota

b. generales & universales -- specialissimae

2. Methodus est relatio disposita, quam praescribit natura

(this includes the following):

a. synthesis: ad sensum accedunt; attendenda adjuncta

b. analysis: a sensu recedunt; simplicia exprome[n]s

3. a. Methodus est rectus partium ejus, quod ad explicandum susci

itur, ordo & dispositio.

b. Method is either "perfect" (perfecta) or "imperfect" (imper-

fecta). In perfect method one precedes I) from that which is

better known to that which is less known and 2) from that

which is most general to that which is less general. In imper-

fect method-which does not necessarily imply defects or

superfluousness-one precedes in the inverse order (gradus in-

versus) and one uses induction.

4. a. Methodus Ramo est dispositio, qua de multis enunciatis homo

geneis suoque vel syllogismi judicio notis, id, quod absoluta

notione primum est, primo loco disponitur, quod est secundu

secundo, quod tertium tertio, & sic deinceps. Ideoque hic sem

per a generalibus proceditur ad specialia. Haec einim sola &

unica procedendi via est (ut solide P. Ramus defendit) ab ante-

cedentibus ad consequentia ...

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS o09

TABLE J. Method/Logic/Petrus Ramus (conti

b. Philipp Melanchthon only touches upon isolated

ing to method; in doing so, he (so Erytropilus imp

not come into conflict at all with the method of Petrus Ramus.

5. a. Philipp Melanchthon divides method (methodus = viae) into

two categories:

I) analytic (analytica): posteriores -> priores;

inductio singularium & specialium ->

generalissimum

2) synthetic (synthetica): priores & notiores -> posteriores &

ignotiores

generales & universales -- speciales &

singulares

b. Synthetic method (= ordo) is referred to by Philipp Melanch-

thon and by Petrus Ramus as method; Ramus does not discuss

analytic method at all.

c. Frisius notes that it is the intention of Ramus-some of his

views notwithstanding-to agree with Melanchthon's views on

method.

6. a. Methodus est dianoia variorum axiomatum homogeneorum

pro naturae suae claritate praepositorum: unde omnium inter se

convenientia judicatur, memoriaque comprehenditur ... ab

universalibus ad singularia . . . sola & unica via proceditur ab

antecedentibus omnino & absolute notioribus ad consequentia

ignota.

b. Casmann refers to Melanchthon's method as nova methodus

Philippi; he describes it as quae monstrat certam rationem trac-

tandi & explicandi membrum aliquod integri corporis.

7. Method is not defined or directly described; it is merely noted that

the discipline of logic consists of three parts, and each part must

be methodically explained.

8. Horstius does not accept the Ramists' (Ramistae) methodus unica.

a. Ramists argue for the methodus unica; one should, so they say,

always begin with universals when seeking knowledge; to use

other methods would be "injurious" (contraria).

b. Horstius answers by making the following observations:

I) The universals used in theoretical disciplines are "principles"

(principia) while those universals used in practical disciplines

are "the final result" (finis); those two kinds of universals

belong to two completely different classes.

2) To use other methods is not injurious but merely "differ-

ent" (diversae).

c. Rudolph Goclenius attempts to reconciliate these two opinions

by concluding that the methodus unica does not negate the fun-

damental distinctions between species (which apparently also

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IIO RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLE J. Method/Logic/Petrus Ramus (continued)

applies to Horstius's two classes of universals). Horstius d

not completely reject this reconciliation (haec conciliatio n

omnino improbanda est, modo ab ipsis quoque Ramaeis ea

ratione intelligatur).

9. Cramer notes that in his edition of Becmann's textbook on "Phil-

ippic" (i.e., "Melanchthonian") logic he has combined Ramist

method (methodus Ramea) with the order of Aristotle (Aristotelis

ordo).

io. a. Methodus ... est instrumentum dianoeticum bene ordinandi

res diversa & varias secundum prius & posterius, commodio

cognitionis gratia.

b. Timpler divides method into methodus inventionis and me

dus doctrinae; the latter is either perfecta or imperfecta, while

perfecta is either universalis or particularis.

c. Methodus unica can only be used to describe (the sub-categ

of) methodus doctrinae perfecta universalis.

Numbers 4, 5, 6, and 7 all purport to be works on logic w

combine the views of Petrus Ramus and Phillip Melanchthon

they go in very different directions with respect to the concep

method. Numbers 4 and 6 essentially adopt a view on method

ilar to that of Ramus, and both regard Melanchthon to be in

mony with Ramus.20 On the other hand, number 5 basically acc

a view on method similar to that of Melanchthon but considers

Ramus to be in harmony with Melanchthon.21 Number 7 goes

neither direction. Instead, this work appears to equate method wi

logic itself.22

Number 8 attacks the Ramists with regard to method but th

appears to accept a compromise between Ramist and Anti-Ram

views offered by Rudolph Goclenius the Elder. 23 Number 9 claim

to be a "Melanchthonian" logic textbook. It uses two differen

Latin terms, methodus and ordo, to state the use of material allege

taken from both Ramus and Aristotle.24 Number Io is a logic text

20Schramus, 53-54; Neander, I59I, table before 251 (252).

"2Erytropilus, L4-L4v; Casmannus, 292-309.

22Frisius, 1590, 98-IOI, table after III.

23Sengebehr, 54-54V (55-55v).

24Horstius, 393-95.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS iii

book by Clemens Timpler (1563/4-1624) wh

title, is an independent work.25 It is very crit

odus unica.26 Yet many other independent w

ample, logic disputations held in an academy

born, Nassau under the supervision of Hein

Gutberleth, and Johann Heinrich Alsted in

present definitions of method which are almo

tions given by Petrus Ramus himself.27

Ramus is one of the authorities whom Cl

tions frequently in his own writings; these fr

ities are tabulated in Table K.28 Timpler was a

at a school in the town of Steinfurt, Westphal

K lists his citations of Petrus Ramus. He makes much less use of

Ramus than he does of Aristotle, Cicero, or Bartholomaeus Ke

ermann (1572/3-I609).3° Timpler's textbook on logic contains t

bulk of his citations of Ramus.31

Items 2a, 2b, and 2c in Table K list the number of times that

various philosophical schools are mentioned. Item 2a refers to "A

istotelians" (Peripatetici, Aristotelici, interpretes Aristotelis, ii, qui A

istotelem sequuntur). Item 2b refers to "scholastics" (scholastici, nom

nales). The citations in 2c pertain in various ways to Petrus Ramus.

Number 3 in Table K lists the five authors associated with Ramus

who are cited most often in Timpler's writings. Friedrich Reisn

25Cramerus, I.

26Timplerus, 1612.

27"Quaestio 9. An Methodus doctrinae sin tantum unica? Ramus unicam tantu

Methodum doctrinae esse docet, quae ex Aristotelis sententia ab universalibus ad s

gularia, seu a generalibus ad specialia; & sic ab antecedentibus omnino & absolute n

tioribus ad consequentia ignota declaranda progrediatur. Quae sententia etsi vera e

de methodo perfecta & universali, de qua etiam Ramus videtur loqui: tamen falsa e

de methodo doctrinae in genere acceptae." Ibid., Liber IV, Caput 8, Questio 9 (72

30).

28Dauberus and Munichius; Gutberleth and Schefferus; Alstedius and Figulus. Con-

cerning the Herborn Academy, refer to the recent monograph by Menk.

29Most of this information is given in Freedman, 1988I, 128-30, 134, 142, 163. Most

of Timpler's citations of Ramus, Talon, and other authorities associated with Ramus

are found in his textbooks on logic and rhetoric; for this reason the citations found in

each of these two textbooks are listed here. Timplerus, 1612 and 1613.

3°See Freedman, I988', and I9882.

3IThe use of Cicero's writings by Timpler is discussed in Freedman, 1986, 234-35,

249. Concerning Keckermann and Timpler's use of Cicero, also refer to Freedman,

I988', 32-33, 122-24, 156-57, 473-74, 561-62, 576 (and to the other pages referred

to in the index of this volume).

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

II2 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLE K. Ramus, "Ramists," and Selected Other Authoriti

within the Writings of Clemens Timpler (I563/4-I62

( ) = number of total citations within Timpler's writings

[ ] = number of citations within Timpler's Logic textbook

{ } = number of citations within Timpler's Rhetoric textbook

I. a. Aristoteles (1783 <- [212] {99})

b. Sacred Scripture (888 <- [8] {64})

c. Cicero (472 <- [26] {281})

d. Plato (I61 <- [ 5] {9} )

e. Keckermannus (140 <- [40] {73})

f. Zabarella (Io8 <- [33] {6})

g. Suarez (106 <- [o] {o})

h. Quintilian (87 <- [4] {79})

i. Aquinas (84 <- [3] {o})

j. Seneca (8I <- [I] {I})

k. Petrus Ramus (8I <- [68] {8})

2. a. Peripatetici (87 <- [46] {2}); Aristotelici (12 <- [5] {I}); inte

tes Aristotelis (5 <- [I] {o}); ii, qui Aristotelem sequuntur

[I] {o})

b. scholastici (76 <- [o] {o}); nominales (2 <- [o] {o})

c. Ramaei; Ramistae (27 <- [I5] {5}); Rami discipuli (II <- [9] {o});

Rami sectarii (3 <- [3] {o}); schola Ramea (12 <- [7] {2}); ii, qui

Ramum sequuntur (9 <- [6] {3}); Rami interpretes, ex mente

Rami (5 <- [5] {o}); illi, qui Rami reprehendunt (I <- [I] {o})

3. Reisnerus (21 <- (o) {o}); Talaeus (20 <- (2) {I7}); Ursinus (I3 <-

[I3] {o}); Hausmannus (o <-- [o] {I0}); Treutlerus (8 <- [o] {8})

and Omer Talon were students of Ramus in Paris. 32 Wilhelm Urs-

inus and Hieronymus Treutler produced commentaries on Ra

mus's logic.33 Hermann Hausmann (1541-1606) was a colleague o

Timpler's at the Academy in Steinfurt, Westphalia. Hausmann pro-

duced a "Philippo-Ramist" textbook on rhetoric.34

32However, the three passages in Timpler's metaphysics textbook which mention

Ramus are all noteworthy; they shall be discussed shortly. Two of these passages ar

mentioned in numbers I and 2 of Table I.

33In his textbook on optics Timpler appears to regard Friedrich Reisner as the mo

important authority on this subject matter; see Freedman, I988I, 410-II, 713, 82

Concerning the relation between Ramus and Talon see the two works by Ong cit

in footnotes 2 and 3.

34Ursinus; Treutler and Assaeus; Treutler. Timpler cites Ursinus's commentar

however, he does not yet mention any work on logic written by Treutler. Timpler

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS 113

The term "Ramist" is never defined or explained

is not clear whether a Ramist is someone who follows Ramus all

of the time, most of the time, some of the time, or only with respect

to individual points of academic doctrine. Timpler never mentions

how he would distinguish between the groups of people whom he

refers to in 2c of Table K as "Ramists" (Ramaei, Ramistae), "disci-

ples of Ramus" (Rami discipuli), "sectarians of Ramus" (Rami sec-

tarii), those belonging to the "Ramist School" (schola Ramea),

"those who follow Ramus" (ii, qui Ramum sequuntur), as "interpret-

ers of Ramus" (Rami interpretes, ex mente Rami), and "those who re-

buke Ramus" (illi, qui Rami reprehendunt). It is also unclear if or to

what extent Timpler would regard all of the five individuals listed

in number 3 of Table K-i.e., Hausmann, Reisner, Talon, Treut-

ler, and Ursinus-as Ramists.

Clemens Timpler's own very eclectic manner of using Ramus

and individuals in some manner associated with Ramus is evident

from Table L. 3 In passages I and 2 Timpler's opposition to Ramus

centers around the latter's intention to place certain concepts within

the realm of logic while Timpler prefers to assign those same con-

cepts to the domain of metaphysics. 36 However, in passage 3 of Ta-

ble L Timpler has the same opinion as Ramus with reference to the

term ars.

In passage 4 of Table L Timpler sides with what he refers t

"Ramists" (Ramei) against Ramus, "those who follow Ramus"

complures philosophi, qui Ramum sequuntur), and a number of o

authors. In passage 5 Timpler criticizes both "those authors

have followed Ramus" (illi, qui Ramum secuti) and "those aut

who oppose Ramus" (illi, qui Ramum reprehendunt). In passa

Timpler argues in favor of his own interpretation of Ramus's vi

on efficient causes against the interpretation(s) of Ramus given

other individuals.

textbook on rhetoric cites a work by Treutler titled De methodo eloquentiae; a copy of

this latter work could not be located while researching this article.

3SHausmannus, I605 and I6I5. Hausmann also presided over a number of dispu-

tations on logic; for example, see Hausmannus and Oldenburgius. Concerning Haus-

mann's career at Steinfurt, see Freedman, I988I, 54, 56, 499, 750.

36Timplerus, I605; Timplerus, 1604. Both of these textbooks were reprinted; see

Freedman, I988I, 748, 750-52, 754, 760-65. Timpler's textbooks on logic and rhetoric

were cited in footnotes 24 and 27, respectively. In each of the passages i through Io

the relevant page numbers can be determined by finding the correct book, chapter, and

question numbers.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

II4 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLE L. Mentions of Ramus and "Ramists" within

Timpler's Writings: I Examples

M = Timpler's Metaphysics textbook; PN 1 = Timpler's General

Physics textbook; L = Timpler's Logic textbook; R = Timpler's Rhe

oric textbook

L = Liber (Book); C = Caput (Chapter); Q = Quaestio/Problema

("Question")

I. M: L3C2QI: Utrum ad Metaphysicam pertineat, agere de causis,

& quomodo?

Timpler states that general discussion of causality belongs within

the discipline of metaphysics and attacks the view of Ramus that

this should only be done within the discipline of logic.

2. M: L3C3QI: An doctrina generalis de subiecto & adiuncto pertin-

eat ad Metaphysicam?

Timpler answers affirmatively, and attacks the view of "Ramus

and all of his disciples" that general discussion of subject and

predicate can only be given within the discipline of logic.

3. PN 1: CIQ2: An Physica sit ars, & quidem contemplativa?

Timpler answers to the affirmative, supporting recentiores Philo-

sophi, praesertim illi qui sunt a Ramo against what he refers to as

the tota schola Peripatetica.

4. L: LICIQI5: An Logica recte distribuatur in Inventionem & Judi-

cium?

Cicero, Quintilian, Rudolph Agricola, Luis Vives, Ramus, and alii

complures philosophi, qui Ramum sequuntur all answer this ques-

tion to the affirmative. Timpler disagrees; he gives io arguments

for his own view, citing "Ramists" (Ramei) within two of them.

5. L: LIC3Q9: An potentia explicandi & probandi sint affectiones

argumentorum?

Timpler answers this question affirmatively; when responding to

objections he criticizes illi, qui Ramum reprehendunt as well as

illi, qui Ramum secuti.

6. L: LIC6QI: An efficiens recte definiatur causa externa a qua effec-

tum est?

Timpler argues this question to the affirmative, and states that

those who interpret Ramus's definition thereof differently are mis-

taken.

7. L: L2C2QI: An antecedens, consequens, & connexa sint species

argumentis artificialis: & quidem ab aliis realiter dis-

tinctae?

Timpler notes that Ramus makes no express mention of the terms

antecedens, consequens, and connexa in the first part of his logic

textbook. Timpler then proceeds to give five arguments for the

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS II5

TABLE L. Ramus - "Ramists" / Timpler (continued)

affirmative position; Timpler uses material from Guilielmus Ur

nus's commentary on Ramus's logic textbook in favor of this p

sition.

8. L: L3C2Q3: Quid sit Enuntiatum affirmatum vel negatum?

Timpler gives five definitions of affirmative and negative enun

tion: two by Aristotle, one from an early edition of Ramus's lo

textbook (Ramus in editione suae Dialecticae, quam Talaeus com

mentario illustravit), one from a later edition of Ramus's logic

textbook, and one by "other logicians." Timpler accepts the def

nitions by Ramus, but notes that those from the earlier edition

better.

9. L: L3C3QI: An Enuntiatum secundum materiam, & quidem rec

dividatur in commune & proprium: & commune ru

sus in definitum & infinitum: & definitum in univer-

sale & particulare?

Timpler answers this question to the affirmative. He attacks Ra-

mus's classification of enuntiation: Bisterfeld [in his own edition of

Ramus's logic textbook] has "corrected" Ramus here.

Io. R: L3CsQ2: Quotuplex sit Synecdoche?

Talaeus, other Ramists (alii Ramaei), and Hausmann classify syn-

ecdoche into various sub-categories; Timpler disagrees, and then

gives his own classification of these sub-categories.

i . R: L3C7Q4: Unde Ironia in oratione cognoscatur?

Quintilian, Talaeus, Keckermann, and Hausmann all give different

answers to this question. Timpler accepts the answer of Haus-

mann here to the effect that irony can only be understood when

words are correlated with the intent of the given person.

In passage 7 of Table L Timpler obviously regards Ramus as an

authority. In passage 8 Timpler accepts Ramus's definitions of af-

firmative and negative enunciation as given in an earlier-as op-

posed to a later-edition of Ramus's logic textbook. In passage 9

Timpler notes that Bisterfeld's edition of Ramus's logic has im-

proved upon Ramus's own less than adequate classification of

enunciation. In passage 10 Timpler disagrees with Hausmann with

respect to one issue but in passage I I Timpler agrees with him with

respect to a different issue.

On the basis of these eleven passages it is clear that there is no

simple formula which explains how Ramus or those individuals

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

II6 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

somehow connected to Ramus are utilized in the writ

Clemens Timpler. It is also evident from passages 3, 4, 6

9 that individual Central European authors of the period

1570 and 1630 could interpret or reinterpret Ramus's views o

cific points of doctrine in different manners. Clemens Timpl

in fact only one of a great many authors active during thi

who all used Ramus's writings in a complex variety of w

The variety of ways in which Ramus appears with

sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century writings printed in

tral Europe is also evident in the 21 examples of such writ

ib, 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b, 5a, 5b, 5c, 6a, 6b, 7, 8a, 8b, 9,

IIa, lib) given in Table M.37 Items Ia and ib are two gr

textbooks used at the Academy in Herborn. Item Ia is "P

Ramist" while Ib is "Mauritian-Philippo-Ramist." Items 2a

are two textbooks which discuss the rhetoric of Omer Talon. But

they also include diverse additional works which were intended for

use in academic instruction. Item 2a includes commentary

Ovid's poems while 2b includes commentary on 22 psalms from

the Old Testament.

Items 3a and 3b are two editions of Ramus's logic textboo

which show differences in content. 38 Items 4a and 4b are two work

which according to their titles discuss the logic of both Philip

Melanchthon and Petrus Ramus. Yet they are diverse in form

well as in content.39

Items 5a, 5b, and 5c are three works on logic by Friedrich

Beurhusius (I536-I609). Beurhusius was rector of a school in

Dortmund and a well-known partisan of Ramus.40 Item 5a is on the

logic of Aristotle, Boethius, and Cicero; 5b intends to compare the

logic of Ramus with that of Melanchthon; 5c is devoted to the logic

of Ramus alone. These three textbooks most probably were pub-

lished in order to fulfill diverse instructional requirements at the

Dortmund School as well as other academic institutions. Severinus

37Library locations and call numbers for those copies of Ia through i ib used in Tab

M are given in the bibliography.

38This can be observed on the basis of the dichotomous charts which summarize

the contents of each commentary; see Rodingus (Table M, 3a), table after I136; and Bi

terfeldius (Table M, 3b), table after 128.

39Erytropilus's text consists mainly of tables with short commentary; Casmann's

text is narrative. Erytropilus directly contrasts the views of Ramus and Melanchtho

on individual issues while Casmann does not wish to highlight such contrasting view

40Concerning Beurhusius, see Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, 2: 584-85.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS 117

TABLE M. Late Sixteenth- and Early Seventeenth-C

Writings Printed in Central Europe which pertain to Petr

21 Examples

Ia. Grammatica latina Philippo-Ramea, ad faciliorem puerorum cap-

tum perspicua methodo breviter conformata, & duobus libris dis-

tincta. Addita sunt passim tabulae cum generales, tum speciales;

ex quibus methouds cognosci potest. Herbornae: Excudebat

Christophorus Corvinus, I591.

ib. Alstedius, Joannes-Henricus, praes. and Coccejus, Sigmundus,

resp. Compendium grammatices latinae, harmonice conformatae,

& succincta methodo comprehensae: quam non inepte quis

dixerit Mauritio-Philippo-Rameam. In illustri Herbornea publicae

censurae subjectum. Herbornae Nassoviorum: I6I0.

2a. Beurhusius, Fredericus. Audomari Talaei rhetoricae, P. Rami

praelectionibus observare, rudimenta. Addita ad finem Ovidianae

elegiae analysi. Tremoniae: Excudebat Alb. Sart., 1582.

2b. Frisius, Paulus. Epitome rhetorices Audomari Talaei collecta ...

Huic adjecti sunt . . . comparationum rhetoricarum libri duo.

Quibus elementa rhetorices Philippi Melanchthonis cum praecep-

tis partim logicis Petri Rami, partim rhetoricis Audomari Talaei

breviter modeste conferuntur. Addita est Psalmi XXII. analysis

logica & rhetorica. Francofurti: Apud heredes Andreae Wecheli,

Claudium Marnium & Io. Aubrium, I600.

3a. Rodingus, Guilielmus. P. Rami Regii Professoris Dialecticae libri

duo, ex variis ipsius disputationibus, et multis Audomari Talaei

commentariis breviter explicati. Francofurti: Apud haeredes An-

dreae Wecheli, 1582.

3b. Bisterfeldius, Johannes. Rameae dialecticae libri duo: propositi

noviter et expositi. Sigenae Nassoviorum: Ex officina Christo-

phori Corvini, I597.

4a. Erytropilus, Rupertus. Tabulae generales in Dialecticam P. Rami,

quibus ex altera facie opponuntur tabulae ex praeceptis Dn. Phil-

ippi Melanchthonis confectae. Lemgoviae: Excudebantur in offi-

cina typographica Conradi Grothenii, 1588.

4b. Casmannus, Otho. P. Rami Dialecticae & Melanchthonianae col-

latio: institutae ac proposita lectionibus privatis Helmstadii. Ha-

noviae: Apud Guilielmum Antonium, 1594.

5a. Beurhusius, Fredericus. M. T. Ciceronis, Dialecticae libri duo.

Ex ipsius Topicis; aliisque libris collecti, ex Aristotele vero Boet-

ioque uspiam completi, & propriis ipsius exemplis illustrati. Ad-

ditis etiam brevius explicationum collationumque notis. Coloniae:

Apud Gosvinum Cholinum, I583.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

II8 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLE M. Writings which Pertain to Petrus Ramus (con

5b. Beurhusius, Fredericus. P. Rami Dialectici libri duo: et h

gione comparati Philippi Melanth. Dialecticae libri quatuo

explicationum et collationum notis, ad utramque conform

tionem uno labore addiscendam. (Mulhusii): (Apud haered

Georgii Hantzsch, impensis Otthonis a Riswick), 1586.

5c. Beurhusius, Fredericus. Petri Rami Regii Professoris Dial

libri duo. Defensio ejusdem dialecticae per scholasticas qu

dam interpretationum, animadversionum, triumphorum,

emendatinum disquisitiones. Francofurdi: Apud Andreae W

heredes, Claudium Marnium, & Ioann. Aubrium, 1590.

6a. Sluterus, Severinus. Anatome logicae Rameae, qua ipsa pr

primum perpicue dissecantur & explicantur: deinde singul

bratim in utramque partem perpetuis obiectionibus & resp

ibus, partim a Peripateticis motis, partim ab auctore recen

cogitatis solidissime disputatur & examinantur. Frincofurt

D. Zachariam Palthenium, I608.

6b. Sluterus, Severinus. Anatomia logicae Aristoteleae sive syncrisis

logica, qua primo ipsa praecepta, ex organo Aristotelis method-

ice proposita, celebriorum interpretum glossis explicantur:

Deinde quid Ramei in iisdem desiderent, indicatur: Tertio de-

nique diversae Aristotelicorum & Rameorum sententiae, in con-

sensu, & dissensu comparatur, ut quid verum falsuve sit, liquido

congoscatur. Prostat in nobili Francofurti Paltheniano, I6Io.

7. Bergius, Conradus. Artificium Aristotelico-Lullio-Rameum in

quo per artem intelligendi, logicam: artem agendi practicam: artis

loquendi... elaboratum. Bregae: Typis Sigfridianis sumptibus

Joh. Eiringi & Joh. Perferti, 1615.

8a. P. Rami Dialectica, cum praeceptorum explicationibus, disquisi-

tionibus, & praxi nec non collatione cum Peripateticis. Ex Za-

barellae, Schegkii, Matth. Flacc. Illyrici, Rod. Goclenij, Fr.

Beurhusij, loan. Piscatorij, & Rodolph. Snellij commentarijs &

praelectionibus. Collecta a M. Christophoro Cramero . . . aucta

plurimis in locis in usum logicae studiosorum edita a Rodolpho

Goclenio. Ursellis: Apud Cornelium Sutorium sumtibus Iohnae

Rhodij, 1600.

8b. Goclenius, Rodolphus, praes. and Chesnecopherus Suecus, Nico-

laus, resp. Isagoge optica cum disceptatione geometrica de uni-

verso geometriae magisterio, hoc est, geodaesia rectarum per ra-

dium, & aliis quaestionibus philosophicis, iuxta aureum P. Rami,

methodum concinnata, in inclyta Marpurgensi Academia pro in-

signibus magisterii Philosophici consequendis publica ad dispu-

tandum proposita. Francofurti: Apud loan. Wecheli viduam,

sumtibus Petri Fischeri, I593.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS 119

TABLE M. Writings which Pertain to Petrus Ramus (con

9. Petri Rami Arithmeticae libri duo, et Algebrae totidem:

Schonero emendati & explicati. Eiusdem Schoneri libri d

De numeris figuratis; alter, De logistica sexagenaria. Fran

Apud heredes Andreae Wecheli, 1586.

ioa. Snellius, Rudolphus. Partitiones physicae methodi Rame

bus informatae: exceptae olim ex dictandis ejus ore in sch

Marpurgensi. Nunc primum in lucem editae. Hanoviae: A

Guilielmum Antonium, 1594.

iob. Snellio-Ramaeum philosophiae syntagma, tomis aliquot

distinctum; quibus continentur I. Generales sincerioris p

phiae Rameae informationes: 2. Dialectica, 3. Rhetorica,

ithmetica, 5. Geometria, 6. Sphaera, seu Astronomia, 7.

8. Psychologia, 9. Ethica; Rhodolphi Snellii... commen

bus succinctis & accuratis; sed cum aliorum huius ani viro

lectissimis observationibus ac notis studiose passim collat

auctis; explicata: quibus praefatio D. Rhodolphi Goclen

praefixa est. Tomo autem primo hic post praefatione sub

vera vereque Ramea recte philosophandi ratio. Sequentib

ac separatis tomis reliqua sequentes disciplina. Francofur

officina typographica Ioannis Saurij, impensis haeredum

Fischeri, 1596.

i a. M. Cornelii Martini Antvverpii adversus Ramistas dispu

subjecto et fine logicae ... A Friderico Beurhusio in scho

Tremoniana. Conrado Hoddaeo D. in Gymnasio Gottingen

Heizone Buschero in schola Hannoverana. Lemgoviae: Sum

bus Magni Holstenii bibliopolae Hannoverani, 1596.

IIb. (Corvinus, Jodocus.) Tetramerum autoschediasticum pro

sione sententiae Andreae Libavij, de apodixi Aristotelea c

mentem Petri Rami, adversus sana sophismata & virulent

calumnias Ioannis Bisterfeldii cuiusdam sine causa furentis. Cum

praefatione And. Lib. ad omnes eruditos logicos. Francofurti:

Excudebat Ioannes Saurius, impensis Petri Kopffij, 1596.

Sluterus published two different logic textbooks: 6a is on the log

of Ramus while 6b is on the logic of Aristotle. Sluterus probabl

wrote these two textbooks because he used both the writings of Ar-

istotle and the writings of Ramus when he taught logic.4I

4'On the title pages of 6a and 6b Sluter is referred to as Scholae Stadiensis Rector

i.e., the principal of the school in the town of Stade. Also refer to the work by Slut

referred to in footnote 9 and cited in the bibliography.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

120 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

Item 7 is a logic textbook which purports to be Aristo

Lullian, and Ramist. Number 9 combines Lazarus Schoner

tion of two works by Petrus Ramus on mathematics with

Schoner's own mathematical works. Schoner was an avid follower

of Ramus.42

Items 8a and 8b are two works for which Rudolph Goclenius the

Elder bears responsibility. The first is on Ramus's logic, but from

the title it is evident that it is more than just that. In this work the

logic of Ramus is explained with the use of writings by Friedrich

Beurhusius, Matthias Flacius Illyricus, Rudolph Goclenius the El-

der, Johannes Piscatorius, Jakob Schegk, Rudolphus Snellius, and

Jacobus Zabarella. Christophorus Cramerus apparently collected

the material used within this work; Rudolph Goclenius edited it for

the use of logic students.43 Item 8b is a disputation held in partial

fulfillment of the Master of Arts degree requirements of Nicolaus

Chesnecopherus, a Swedish student at the University of Marburg.

Chesnecopherus was the author of this disputation on optics, ge-

ometry, and geodasy; Goclenius was his teacher.44 According to the

title page the method of Ramus is used within this work; Ramus

is cited a number of times in this disputation's section on geodasy.45

Items Ioa and Iob are two philosophical works by Rudolph Snel-

lius who was a professor at the University of Marburg for part of

his career.46 The appearance of Ramus on these title pages is some-

what deceptive. The text of Ioa mentions neither Ramus nor his

method. In iob Snellius defends Petrus Ramus against one of his

major critics; however, in this latter work Snellius also has sharp

criticism for what he refers to as "Pseudoramists" (Pseudoramei).47

Items I Ia and lib are examples of polemical writings by indi-

viduals who were in favor of or opposed to the use of Ramus's writ-

42Concerning Lazarus Schoner's life and works, see Strieder, 13: I85-88.

43This work contains the classification of philosophical disciplines which is given

in Table D.

44Chesnecophorus wrote the dedication to this disputation (A2-A4v); the text

this dedication (A4-A4v) makes it clear that he is also the author of the disputati

It also contains prefaces by Lazarus Schonerus (fol. BI-Blv) and Rudolph Gocleni

(B2-B2v).

45See pages 34, 35, 36, 40, and 43 of this disputation.

46Concerning the career of Rudolphus Snellius, see Bangs, 37-38 and Joche

4: 648-49.

47See 180-83 of this work (i.e., Iob of Table M) and the discussion given later

this article.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS 121

ings. Such writings appeared frequently in C

about 1570 until at least the I630s.48 Item i a

Ramus works written by Friedrich Beurhus

daeus, and Heizo Buscher, who taught at Luth

mund, Gottingen, and Hannover, respective

Jodocus Corvinus, who defended the anti-Ram

Libavius, a Lutheran, while attacking the views

feld, a Calvinist.50

From the information presented in Tables

I, J, K, L, and M it is clear that terms such as "

Ramist," and the like lose most of their valu

the context of primary source data which pe

most all of the writings presented in Tables B

connection with academic instruction; the ne

stitutions were different.5I Therefore, indiv

used and interpreted Ramus differently and

various other authors.

The eclectic manner in which Timpler used Ramus and those

whom he associated with Ramus is evident from Table L. This

same attitude toward Ramus was held by many of Timpler's

temporaries. Rudolph Goclenius's commentary on the logic o

mus was briefly described above and listed as item 8a of Tab

This work contains a classification of philosophical discip

which has very little in common with the classifications giv

other commentaries on Ramus's logic or given by Ramus's fo

ers.52 However, the discussion of method given by Gocleni

very similar to views on method held by Petrus Ramus hims

48Two additional examples of such polemical writings are given here: Wackeru

Helmoldus; Fabricius and Wolffen von Gedenbergk. The title pages identify Wac

and Fabricius as principals of schools in G6ttingen and Mulhausen (Saxony), r

tively. The first disputation is sharply critical of Ramus while the second one i

portive of him.

49Concerning Beurhusius, see 5a, sb, and 5c of this table and footnote 37. Wi

gard to Heizo Buscher, see Jcher, I: 1512 and Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 3:

sOAndreas Libavius taught at Jena, Rothenburg on the Tauber, and Cobur

Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, i8: 530-32; very little is known about Bisterfeld;

of Table M and the documents in Wiesbaden SA: Abt. 95, Nr. 324, 5 . Johann St

statement to this same effect from the year 1572 is given in Ie of Table N.

5sMissing text for footnote 51.

52Compare Table D with Tables B, C, E, F, G, and H.

s3Goclenius's discussion of method is given in pages 667-701 of that same w

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

122 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

Goclenius also shows an eclectic attitude towards Ramus in other

writings as well.54

It has already been noted that Johann Heinrich Alsted presided

over a logic disputation on method in 1612 which largely echoes

Ramus's views on that subject. Yet in other works Alsted takes

positions much more distant from those associated with Ramus.

Alsted's presentation of two classifications of philosophical disci-

plines by followers of Petrus Ramus were given in tables E and F;

yet Alsted's own classification of philosophical disciplines is very

different from both of them. In a logic disputation on causes pre-

sided over by Alsted at the Herborn Academy in I6 1 it is noted

that generally speaking there are problems with both Aristotle and

Ramus but that Aristotle is the lesser evil of the two.ss The title of

Alsted's "Mauritian-Philippo-Ramist" compendium on Latin

grammar given in item Ia of Table M is further evidence of his in-

dependent attitude towards the use of Ramus in his own writings.

The individual authors who used Ramus between 1570 and I630

normally did so too eclectically to allow the effective use of terms

like Ramist, Philippo-Ramism, and Semi-Ramism as explanatory

factors for the diffusion of Ramus's writings in Central Europe dur-

ing this period. On the other hand, the examination of historical,

institutional, and curricular factors can lead to a much more viable

explanation of this diffusion. The adoption of Ramus's writings

in Central European academic institutions can be understood in

large part by looking at the form and content of the curriculum at

these institutions during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth

centuries.

Central Europe saw a rapid educational expansion beginning

about 550. This growth accelerated rapidly in the 1 570s and 58os

and then continued, though apparently to a somewhat lesser extent,

well into the seventeenth century. 56 Confessional motivations ap-

pear to have played a major role in this expansion. Almost all of

these academic institutions were founded by and/or expanded by

54Refer to the mention made of Goclenius by Gregorius Horstius in number 8 of

Table J.

5s"An Logica Rami sit praeferenda Aristotelis? Respon. Aristotelis habet sua

menda, Rami sua. Nihilominus Rami mihi videtur mendosior." Alstedius and Stu-

boeus, C4.

56See the discussion given in Freedman, I9852, 121-22.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS 123

Lutherans, Calvinists, and Roman Catholics, and some

rect competition with one another.57

Most of these academic institutions in Central E

schools, not universities. Some of the Protestant scho

referred to as scholae triviales due to the fact that the t

logic, rhetoric, and grammar-normally taught to

arithmetic and geometry-were the basic subjects taug

schools during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth

These schools were sometimes attached to universitie

tory schools. In both cases they normally consisted of b

and ten grades.59

However, many of these schools which were not attach

versities proceeded to expand their curriculum in the co

late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Some sch

added one or more additional subjects.60 But others adde

"upper" division offering university-level instructio

phy, jurisprudence, medicine, and theology to what t

came the school's "lower" division.61 The lower division of these

multi-level, "consolidated" schools normally consisted of grad

while the upper division usually did not.62

Logic and rhetoric were usually studied in both the lower and th

upper level of these consolidated schools. They were also stud

at university preparatory schools and again at universities. T

study of grammar was usually reserved for lower level instruction

57The proximity of the Jesuit University of Dillingen (Danube) and the Luthera

consolidated school in Lauingen (Danube) is mentioned in Ibid., 146, I48-49. The

valry between the Jesuit school in Muinster (Westphalia) and the Calvinist schoo

Steinfurt (Westphalia) is discussed in Freedman, I988', 47-48, 490.

58The examples of Neubrandenburg (I5 3) and Juterbog (I579) are given he

"Prima classis . . . Elementa quoque Dialectices et Rhetorices, ut in trivialibus Sch

fieri solet, reliquis lectionibus addemus, et usum artium simul indicabimus." Brach

A6, A8; Grunius; the example of Dessau (1625) is given in footnote 66.

59Refer to the examples given in Freedman, I9852, 138 (footnote 23).

60Such appears to have been the case at schools in Soest and Wesel. See Vogele

I4-15 and Vormbaum, 192-207; Kleine, first pagination, 38-39 and second pagin

tion, 4-6, 10-I4.

6IThe Strassburg school grew in this manner; see Strasbourg StA: AST 319, 3

331, 392, 393, 396, 450, 451 and Schindling. A similar development took place at

Calvinist school in Steinfurt; see Freedman, I988', 47, 489.

62Such was the case in Herborn; refer to Table T. These multi-level schools some

times were given the name Gymnasium illustre; refer to the discussion given in Fr

man, i9852, 121, 141-42.

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I24 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

while metaphysics, physics, and practical philosophy wer

mally left for upper level or university instruction.63

With these institutional developments in mind, we can now

at the information given in Tables N through U. Table N p

four different opinions concerning the academic value of w

by Petrus Ramus. Number I in Table N is a letter byJohann

(I507-I589).64 This letter precedes the text ofHenricus Sch

curriculum plan of 1572 for a Roman Catholic school in S

in Alsace.65

It is important to note that Sturm was a Lutheran who was com-

menting on the use of Ramus at a Roman Catholic school. Petrus

Ramus was Calvinist. Ramus was used in instruction at a number

of Calvinist schools in Central Europe (e.g., Bremen, Dessau, He

born, KOthen, Steinfurt, Warendorf, Wesel) during the late si

teenth and early seventeenth centuries.66 Yet during this sam

period in Central Europe many Lutheran schools (e.g., Brau

schweig, Gottingen, Hannover, Korbach, Laubach, Lemgo, Mar

burg Regensburg, Soest, and Stadthagen) and several Lutheran u

versities (e.g., Giessen and Rinteln) also made at least some use

Ramus's writings.67 And Ramus's works appear to have be

63Practical philosophy usually included ethics, family life (oeconomica) and politic

These three subjects are mentioned in Tables B, C, D, E, G, and H.

64Schorus, 5-7. Concerning Sturm, see Schmidt.

6sWith regard to Henricus Schorus and the Savere school, see Table O and foo

note 87 below.

66Evidence of the use of Ramus and/or Talon at the following schools is given he

I) Bremen: Brevis artium et lectionum index, A3v; ECb6eiLo Scholae Bremanae, B2-B

2) Dessau: Suhle, 24-25; 3) Herborn: see Table T; 4) Steinfurt: see Freedman, 1988

5I, 494-95 as well as Table K, Table L, and footnote 3 5; 5) Warendorf: Meier and Me

ering, 34-35, 48-49; the original of this curriculum plan for the Warendorf school

the year 1594 is located in MOnster, Bistumsarchiv, GV. Warendorf, St. Laurenti

A 5 , B1. I; 6) Wesel: see Kleine, first pagination, 39 and second pagination, 5, 14. A

refer to the discussion given within footnote 70.

67The use of writings by Ramus and/or Talon at the following Lutheran academ

institutions can be documented here: i) Braunschweig: Koldewey, 149, 152; 2) Giesse

"Logicus Organum Aristotelis profitebitur, aut praecepta ex Aristotele desumpta, ac

commodata ad methodum Rami. . ." Privilegia et leges ... Academiae Giessenae

d. 12. Octobr. ann. 1607 [Giessen UA: Urk. Nr. 318, 6; reprinted in H. Wassersch

ben, 20]; 3) G6ttingen: see no. I Ia of Table M and the following: G6ttingen StA: Alt

Aktenarchiv (Schulsachen, Lateinschule), nr. 10, 2b-2f (Delineatio lectionum Pae

gogii G6ttingensis . . Anno [i5]98), 2b; 4) Hannover: see footnotes 47 and 82 as w

as the corresponding passages in the text; 5) Korbach/Corbach: see Table R and fo

note 94; 6) Laubach: Windhaus, I I9; 7) Lemgo: refer to Table S as well as to footnote

94 and III; 8) Marburg: see Table U and footnote 107; 9) Rinteln: refer to footno

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS 125

TABLE N. Four Selected Opinions concerning th

Academic Value of Writings by Petrus Ramus

I. Joannes Sturmius (March I, 1572); 2. Bartholomaeus Kec

(1606); 3. Joannes Gisenius and Gerhandus Schuckmannus

Statius Buscherus (1625)

I. a. Sturm begins by noting that Ramus is used in instruc

at a school in Saverne (Alsace).

b. Sturm says that Petrus Ramus is a good man. The fact

Ramus offends others by freely speaking about Aristot

writings and by using a different method (via & ordo

no consequence. Aristotle acted likewise toward those

preceded him.

c. Similarly, mathematicians cannot be expected to blindly follow

Euclid and Ptolemy.

d. Many academic institutions have defended Ramus's views.

e. Sturm notes that he wishes to use equity and humanity when

judging the views of others. He cannot expect others to use his

own methods in their schools. Each locality is different from the

next and has diverse educational needs.

2. a. Keckermann's "Introduction to Logic" (Praecognita logica) con-

sists of three "treatise" (tractatus) and a long preface.

b. This preface discusses the differences between "Peripatetics"

(Peripatetici) and "Ramists" (Ramei)

I) Keckermann states Ramists have used good definitions in

grammar, geometry, and theology. Ramist definitions and

dichotomies are useful in grammar and geometry but are not

sufficient within the disciplines of logic, ethics, and physics.

2) Keckermann notes that Rudolph Snellius has discussed the

differences between Aristotelian and Ramist philosophy (Ar-

istotelean & Ramea philosophia) in a work published at

Frankfurt in the year 1596. Keckermann quotes extensively

from this work in order to stress the following: Ramists are

too dependent upon definitions and dichotomies; they don't

explain things (res ipsae).

c. Treatise 2 of Keckermann's Introduction to Logic is a short his-

tory of logic. He divides logic into four parts: I. up to the year

I500; 2. from 1500 up to Ramus; 3. Petrus Ramus; 4. from Ra-

mus up to (about) the year I595.

d. In his discussion of Petrus Ramus Keckermann notes the follow-

ing (i.-6.):

I) Ramus rightly criticizes scholastics and "Sorbonists" for hav-

ing corrupted Aristotle's writings; however, Aristotle himsel

should be praised. Ramus and his followers need to distin-

guish between Aristotle's logic and commentaries thereupon.

2) Ramist philosophy is not comprehensive. Ramus has pro-

duced works on grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, and

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I26 RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

TABLE N. Four Selected Opinions/Petrus Ramus (contin

geometry but no works on ethics, on physics, or on ot

[unspecified] disciplines.

3) Ramists concentrate too much on definitions and dicho

and not enough on properties of things themselves. Ram

make academic disciplines the measure of things, where

should be the other way around. They also are too depe

upon ambiguous terms.

4) Ramists confuse metaphysics with logic.

5) Entity (ens) belongs to the first principles of philosoph

Ramist philosophy does not discuss this and does not ha

first principles at all.

6) Keckermann has problems with the methodus unica of

Ramists. They proceed from universals to "those which

more simple" (simpliciores); however, they neglect to p

ceed from universals to species. Method has two species

oretical (i.e., synthetic), and practical (i.e., analytic). In

former one proceeds from most general to most simple

the latter one proceeds in the opposite manner.

3. a. Ramists (Ramei) and Peripatetics (Peripatetici) agree conc

the object (objectum), subject (subjectum) and final result

of philosophy. The object of philosophy is natural entity

naturale). The subject of philosophy is "intellect or inclina

(intellectus vel voluntas). The final result of philosophy sh

be the "restoration of natural unity" (restitutio in integru

naturale).

b. Ramists and Peripatetics disagree concerning the manner in

which one should investigate and acquire knowledge of things

(e.g., in this process the Ramists combine logic and metaphysics

where Peripatetics do not). There are two reasons for this dis-

agreement:

I) Ramists omit many parts of Aristotle's logic because they are

regarded as not useful.

2) Ramists hold to the view that there are general laws which

are basic to all individual academic disciplines. They take

many doctrines out of the category of "special"-and put

them into the category of "general"-academic disciplines.

c. Gisenius and Schuckmannus assert that Ramus's logic should be

studied. Many authors (Chytraeus, Menzerus, Hawenreuterus,

Johannes Regius, and Zwingerus are mentioned) praise Ramus.

In one of his works on logic even Keckermann feels compelled

to praise the value of Ramus's methods as well as Ramus's abil-

ity as a mathematician and as an orator.

d. Zacharias Ursinus has said that Ramus's logic is novel and

should not be used in academic instruction. Gisenius and

This content downloaded from

89.164.29.222 on Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE DIFFUSION OF THE WRITINGS OF PETRUS RAMUS I27

TABLE N. Four Selected Opinions/Petrus Ramus (con

Schuckmannus defend the use thereof while noting tha

not thereby support all of Ramus's views.

e. It is best to use both Aristotle and Ramus when study

f. One should choose between Aristotle and Ramus within the

context of individual points of doctrine. However, many

learned men make the following general distinction: Aristotle is

to be preferred with respect to subject matter while Ramus is

favored with respect to methodology. (Hinc illum tritum:

Aristotelem lego propter res; Ramum propter methodum &

tradendi modum.)

4. a. Ramus's logic should be used in Christian schools. In doing so,

we are following Luther's advice to bring Aristotle's works on

logic into a more comprehensible and useful form.

b. Julius Pacius praises Ramus's logic in a letter written in 1586.

c. For a long period of years Ramus has been used in many schoo

in Lower Saxony, Hesse, and Westphalia. In some universities

one has also made some use of Ramus. In I606 at the Universit

of Giessen it was decreed that Aristotle's Organon should be

studied with the use of Ramus's method.

d. Seneca notes that what is useful and good does not please the

majority. This is why Ramus and his followers (sectatores) have