Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Changing Health Habits by Influencing Societal Choices

Uploaded by

Larr SumalpongOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Changing Health Habits by Influencing Societal Choices

Uploaded by

Larr SumalpongCopyright:

Available Formats

A Framework for Prevention: Changing Health-Damaging

To Health-Generating Life Patterns

NANCY MILIO, PHD, RN

Abstract: A set of propositions is offered to pro- will gain more of what they value in tangible and/or in-

vide a frame of reference for proposed strategies to im- tangible terms.

prove healthful behavior by placing personal choice- The range of options available to them, and the

making in the context of societal option-setting. ease with which they may choose certain ones over

The health status of populations at a given point in others, is typically set by organizations, public and pri-

time is seen as a result of customary personal choice- vate, formal and informal. The more powerful the orga-

making. These choices in turn are limited by both the nization, i.e., the more effective it is in carrying out its

perceived and actual options available to individuals, policies, the more it affects the options available to oth-

depending on their personal and their community's re- er organizations and populations, whether or not these

sources, from which to make choices. Most people, effects are immediately perceived by individuals in

most of the time will make the easiest choices, i.e., their day-by-day choicemaking. Implications for

will do the things, develop the patterns or life-styles, health education strategies are noted. (Am. J. Public

which seem to cost them less and/or from which they Health 66:435-439, 1976)

It is a paradox that health professionals, in their efforts nonprofessional, provider or consumer, make the easiest

to improve people's health-related practices, seem to expect choices available to them most of the time, and not necessari-

more of the ordinary consumer than they do of themselves. ly because of what they know is most healthful. Thus, if it is

Almost all patient and consumer health education assumes, agreed that health-promoting life patterns are a good thing,

explicitly or implicitly, that if people know what is most then the focus for changing behavior should be on the prob-

healthful, they will do it. lem of how to make health-generating choices more easy,

Perhaps the most obvious test of this assumption is to and how to make health-damaging choices more difficult.

look at health professionals themselves. If knowing what is

health-generating were directly related to doing, then surely

we in the health field would be among the most robust in the A Time for Change

nation, slim, agile, nonsmoking, temperate eaters of com-

plementary protein, low fat and cholesterol, low-sucrose, There is increasing national and even international inter-

and nonrefined carbohydrate foods, avoiders of drugging lev- est in the problems of "primary prevention" of disease,

els of alcohol and other artificial mood-changers, evenly "health education," "life-style changes," etc. This is occur-

paced in our daily patterns. This picture is obviously non- ring, in part, because of studies which indicate the historic

existent. Nor do we expect it to exist. Most will recognize and contemporary limitations of medical care for improving

that it is not much more likely for a physician earning the health of populations. Those limits include the narrowing

$85,000 a year to change his life pattern than for a $6,000 a impact that traditional, microbe and infestation-oriented pre-

year hospital aide to do so. However, the potential for life- ventive programs can have on the modern profile of chronic

style change, the array of options available to these two indi- and degenerative illness and violent deaths.'"8

viduals, may differ considerably. A more immediate impetus for serious attention to ill-

The point is that most human beings, professional or ness prevention is the uncontrolled rising costs of personal

health services. This derives from the capital- and energy-

intensive nature of the inpatient facilities and technology

Dr. Milio is Associate in Nursing, Simmons College, and Direc- which dominate health care organization, and is aggravated

tor, Alternatives in Health Care, 255 Massachusetts Avenue, No. by inflation in the national economy. As greater shares of

1010, Boston, MA 021 15. Address reprint requests to her at the health care financing come from governmental sources,

above address. This paper, based on concepts presented by the au- more concerted efforts will be made to control costs. One

thor in the Sybil Palmer Bellos Memorial Lecture at Yale University such major effort is to find ways to prevent major disease en-

School of Nursing, April 9, 1975, was submitted to the Journal on

October 8, 1975, revised and accepted for publication January 16, tities, principally chronic illnesses and accidents.

1976. Two recent developments are focused on this issue. One

AJPH May, 1976, Vol. 66, No. 5 435

MILIO

is the National Health Education and Promotion Bill which sucrose, cars, pollutants, and tensions are readily available

requires health education in delivery systems and sets up to the poor, while at the same time they are deprived of the

mechanisms for nationwide development, testing, and dis- level of protection afforded by the quality of food, shelter,

semination of methods to promote health-generating behav- and environment which sustain the more affluent. The poor

ior. Another important event was the National Conference not only succumb more readily to virtually all disease proc-

on Preventive Medicine. Studies cited above, the 1300 pages esses, they also possess fewer options for getting the damage

of Senate health education hearings, and many Conference repaired or contained through the medical care system.

Task Force papers thoroughly review the "state-of-the-art" These socioeconomic realities thus form the basis for the typ-

of disease prevention, and document the limitations of con- ical life-style or behavior patterns which result in the varying

temporary health services. These will not be reiterated illness profiles of different population subgroups.' -16

here.9' 10 2. Behavior patterns ofpopulations are a result of habit-

Recommendations from these sources concerning what ual selection from limited choices, and these habits of choice

needs to be done cover a broad spectrum. Some groups rec- are related to: (a) actual and perceived options available; (b)

ommend educational programs in the elementary schools, in beliefs and expectations developed and refined over time by

adult education classes, in health services settings using socialization, formal learning, and immediate experience.

small group techniques; or for the general public, using the Ordinary, "average," day-to-day behavior stems from

media and other advertising and mass communications meth- daily choices that are relatively set and no longer con-

ods. Others emphasize federal policy changes not directly re- sciously made. These choices have been limited by what is

lated to personal health services or to conventional educa- actually available to groups of people and what they perceive

tion-information-persuasion methods, such as placing a high to be available or possible. Their knowledge of the possible

tax on cigarettes, the funds to be used in the research and and their perceptions are influenced by what they have

treatment of lung disease. learned in the past, informally and non-verbally as well as

What follows here is a preliminary effort to place in con- formally, and by what they experience.17

text, as an interrelated set of working hypotheses, the well- Applied to consumers, this is a point at which new

founded but seemingly divergent recommendations of nu- health information and knowledge may influence individual

merous groups actively concerned with the problem of en- choice-making under certain conditions.

hancing health-promoting life patterns and/or discouraging 3. Organizational behavior (decisions or policy-choices

health-damaging habits. made by governmentallnongovernmental, nationallnon-na-

tional; non-profit/for-profit, formallnon-formal organiza-

tions) sets the range of options available to individuals for

A Set of Propositions their personal choice-making. Organizational decisions di-

rectly affect the options available to people and/or their

1. The health status ofpopulations is the result of depri- awareness of those options and/or the ease with which they

vation andlor excess of critical health-sustaining resources. may make daily, habitual, selections.'7" 8

Health-sustaining resources include the seminal ones (e.g., For example, federal policy decisions concerning tax-

food) or the synergistic ones (e.g., basic education, health ation, business subsidies, tax incentives, and import-export

services). In any population those subgroups which are de- restrictions affect whether and how much of such items as

prived of sufficient and safe food, water, shelter, and envi- cigarettes and palatable soy protein will be available, how

ronment have great vulnerability to acute, infectious disease widely distributed and advertised, and at what price. These

processes. The poor in Third and Fourth World countries are decisions set the array of options available to various eco-

the most stark examples. The population subgroups which nomic and geographic populations concerning the ease with

are affluent have disease resulting from too much food (e.g., which they may or may not choose such items.

obesity and hypertension) of the highest cost varieties (e.g., As another example, combinations of policy choices by

meat, concentrated sucrose, refined carbohydrates, and such organizations as city government and public and pri-

fats); alcoholic, caffeinated and other drinks, and other dan- vate housing, transportation, and banking firms concerning

gerous relaxants (e.g., drugs, smoking, passive use of lei- land use set the range of options available to population sub-

sure); too rapid transportation and communication-often re- groups concerning where they may or must live and work,

sulting in accidents and in stressful work overloads dealt and the means and speed of their transportation (therefore

with in sedentary posture. Excessive environmental pollu- how physically active they may be, how fatiguing or com-

tion arises from the production-consumption patterns of this pact their day, how clean their air). Such policies also deter-

affluent way of life. Affluent urban Americans are the best mine which of the available array of options are the easier.

example. National governmental decisions concerning the politi-

Somewhere between the very poor and the affluent are cal economy in a country such as China stand in marked con-

the population subgroups, having a low-income but living in trast to those in the U.S.A. The result in China has produced

a relatively affluent or "advanced" society. Low-income forms of social organization such as rural communes and ur-

Americans are not only more vulnerable to acute disease ban neighborhood and industrial-worker networks which fa-

relative to their affluent counterparts, but also sustain more cilitate collective decision-making within organizations. Col-

of the chronic degenerative illnesses and accidents which are lective or small-group decision-making can then become a

integral to the affluence of the wider society. The cigarettes, mechanism by which participants can develop new options

436 AJPH May, 1976, Vol. 66, No. 5

FRAMEWORK FOR PREVENTION

for themselves as well as be supported in the reinforcement clinic which diagnosed her condition has no consistent meth-

of the new choices which they make, concerning community ods to intervene and offer help in her home situation.

and personal health care among other things.'9 -22 For either individual, the physician or the aide, the per-

4. The choice-making of individuals at a given point in sonal and societal resources will not determine whether or

time concerning potentially health-promoting or health- not they will alter their life patterns. But those resources will

damaging selections is affected by their effort to maximize make the likelihood that each one can change-given an ini-

valued resources. Choice is therefore related to the type and tial moderate willingness to do so-either more or less a pos-

amount of: sibility. This is because of the array of options before them,

(a) their personal resources: their awareness, knowl- and because some of those options, health-promoting or

edge, beliefs and skills; those of family, friends, and of oth- health-damaging in their net effects, are easier to choose

er primary (small, face-to-face) groups; available money than others.

and time; convenience concerning distance, travel, trans- 5. Social change may be thought of as changes in pat-

terns of behavior resulting from shifts in the choice-making

portation; the urgency of other priorities; and of significant numbers of people within a population.

(b) societal (community and national) resources: the In order then for life-style patterns to alter among indi-

availability of health-sustaining services and resources in viduals in numbers sufficient to affect the incidence of major

terms of cost, distance or location, type, comprehensive- diseases, new, health-promoting options must be available,

ness, program outreach components (e.g., food, housing, and more readily so than health-damaging options, i.e., in

income maintenance, environmental protection, health such a way as to be less costly in dollar and other costs.

services); alternatives to formal services; penalties or loss- People also must be aware of the new options and of what

es incurred, or rewares given, for selection or failure to se- they can gain from selecting them relative to their former

lect given options. choices.

All of these resources implicitly or explicitly limit or 6. Health education, as the process of teaching and

widen the array of options available to individuals for retain- learning health-supporting information can have little signifi-

ing or altering health-related habitual choices, and determine cantly extensive impact on behavior patterns, that is, on per-

the ease with which new, possibly more healthful choices sonal choice-making of groups of people, without the easy

may be made. Any change in pattern would involve some ef- availability of new, or newly-perceived alternative health-

fort or cost and some actual and/or perceived gain. promoting options for investing personal resources.

An example might be the $85,000 a year physician and Typically, what has been regarded as health education

the $6,000 a year aide, both of whom have mild hypertension has focused on providing consumers with information or

and each of whom would benefit by a more healthful life knowledge in order to make them aware of the costs and ben-

style. Given that both are made aware of what shifts in be- efits to their health to be derived from particular behaviors.

havior would be most likely to have health-enhancing ef- The relative lack of other options from which to choose new

fects, it is quite apparent that the physician has a potentially behavior patterns has not been dealt with realistically, partic-

greater opportunity to adopt a more health-promoting pat- ularly for outcast groups, such as rural and lower income. It

tern of daily choices because of his personal resources. is not enough to make people knowledgeable about health-

The physician may conceivably slow the pace of his life promoting choices. The other side of the coin is to provide

by choosing to live closer to his work in the urban medical ready access to health-promoting options.'0023-25

center in a quiet townhouse. He may take more frequent va- The strategy of making health-promoting options easier

cations as a means to relax and thereby diminish the need for is implicit in the small group approach to behavior change,

cigarettes, alcoholic drinks, or other drugs. He would have e.g. weight-reduction, cessation of smoking or alcohol con-

no serious financial problem in obtaining palatable meals sumption. By becoming an integral part of a group which ap-

within caloric-cholesterol-sodium limits in restaurants or spe- proves of certain choices, individuals can more easily make

cially prepared for him alone. Medical center fringe benefits such choices. Thus by choosing low calorie foods they gain

would allow him ample sick leave, medical insurance, pen- the short term reward of group approval and avoid its dis-

sion, and other supportive resources. approval, as well as gaining the longer term reward of weight

The aide earning $6,000, typically a woman, possibly reduction. The reward is apparently greater than in the typi-

with adolescent children, has fewer options for making new cal individual counseling method, making the group ap-

choices. There is virtually no chance for her to find even a proach the more successful.'0

low-paying job in a less hectic environment. Without rapid However, the small group approach is limited for sev-

transit, moving the household to a less congested area is out eral reasons. It is costly to individuals in both time and mon-

of the question, even if such housing were available. To ey, and would be very costly to the delivery system were it

work fewer hours is not an option since her husband is spo- applied extensively enough to impact on the behavior of

radically employed at best. Besides, taking too much time large populations. Its benefits, measured in terms of impact

off may risk her job security. There is little extra time or mon- on groups of people, are not very efficient. This approach

ey to change the family's customary diet, and food and ciga- has successfully reached just over an estimated 2 per cent of

rettes are two of the very few options left for relaxation and all smokers; further, as another common example, up to 4

pleasure. Neither friends nor family, though willing, have out of 5 members of weight control groups may drop out.

enough resources to share to make a difference. The medical There is also some question as to whether the changes in be-

AJPH May, 1976, Vol. 66, No. 5 437

MILIO

havior that do occur are large enough to be clinically signifi- and for-profit, formal and informal. This is done through the

cant.26-28 organizations' capacity to determine policy choices which af-

In one report, a mass media approach was combined fect the allocation and distribution of various kinds of

with small group techniques for clinically high-risk groups. amounts of goods and services and their price, direct or in-

There was an increase in knowledge and change in attitudes direct, to the user. The more powerful the organization, that

concerning health-relevant choice-making, but relatively is, the more effective it is in carrying out its policies, the

little change in actual behavior. Change included a lessening, more it affects the options available to other organizations

but not cessation of smoking, and a drop in the number of and populations, whether or not these effects are immediate-

eggs eaten-a change which also occurred in the non-experi- ly perceived by individuals in their day-by-day choice-mak-

mental population apparently related to the economic situ- ing.

ation of the communities involved.29 Choice-making regard- Implicit in this view of organizational decision-making

ing physical activity and exercise was unchanged. and individual choice-making as they affect health-relevant

This non-change is understandable in terms of the ear- patterns is the notion of a pyramid of decisions. The deci-

lier discussion about gains and losses of resources. Activity sions taken at the "higher", more powerful organizational

patterns reflect daily concentrations of work, job, leisure, levels, set the range of options available at lower levels. This

housing location, available transportation, family responsi- may be seen in the ways in which both federal government or

bilities, etc. As such, they are integral to both family and multinational and large scale corporation policies concerning

community choice-making. Even a strong desire by an indi- food, energy, transportation, or antipollution enforcement ul-

vidual to alter and increase his or her physical activity would timately affect not only the policy-choices of public and pri-

require a sustained effort if the readily available options in vate bodies at state and local levels, but also the individual in

the family-home, job-community favor time-consuming and his and her daily choices about diet, residence, exercise and

sedentary or light activities. Under these conditions, a burst pace of life. ' 8

of effort at increased exercise is likely to subside and accom-

modate again to customary, more readily-taken options for

less physically exerting activity patterns of household and Implications

community.30

The small group approach seems somewhat more effi- Given this framework, strategies for encouraging

cient when applied to patients, especially those who are seri- health-promoting choices may also be put in perspective.

ously ill.9 31 This again is understandable. III people have rel- Their minimal aim, for example, might be to broaden the

atively more to gain by making choices which will diminish range of options available to people and to make health-

their symptoms and restore their ability to live more pain- promoting choices easier and/or to diminish health-damaging

lessly and with less effort. options by making them more difficult to choose. For the

As awareness of the limitations of traditional health edu- most widespread impact, the focus might be on national-lev-

cation grows, a contemporary concept is developing which el policy-making which would in turn change the range of op-

includes, along with information and motivation, change- tions for the largest number of people, i.e., the national popu-

making in the living environment, conceivably to the broad- lation. Selected populations, those most vulnerable to ill

ening of healthful options for personal choice-making.32 health because of the limited healthful options available to

There is also evidence of more comprehensive and planned them, might also receive special attention.

approaches to health education, with increasing emphasis on This frame of reference can also help assess or project

cost-effectiveness and the evaluation of results, including the the relative effectiveness of various efforts at behavior

measurement of changes in behavior and health stat- change. For example, a local effort at conveying more knowl-

us. 9' 33-37 edge about healthful diets is not likely to result in changes of

eating patterns unless it is accompanied by a combination of

healthful, low cost, readily available foods-changes which

Summary require effort beyond the individual or small group methods,

and extend to the community public and private organiza-

These hypotheses provide a framework in which health tional structure.

status of populations at a given point in time is viewed as the The question may be raised that this perspective sug-

outcome of customary personal choice-making. These gests a manipulation of behavior, a constraint on freedom.

choices in turn are limited by the actual and perceived op- Quite the contrary, since as this discussion shows, current

tions available to individuals, which reflect their personal policy and allocative decisions clearly constrain personal

and their community's resources. Most people, most of the choice-making, even if not so perceived by many people.

time will make the easiest choices, that is, will develop the This framework rather suggests strategies which will en-

patterns of behavior or life-styles which seem to cost them hance the freedom to choose, making it readily possible for

less and/or from which they will gain more of what they val- individuals and groups who now have difficult options to

ue in tangible and/or intangible terms. create healthful lifestyles. Those who wish to pursue health-

The range of options available to populations, and the damaging patterns would still be able to do so.

ease with which they may choose certain ones over others, is These are working hypotheses, not yet sufficiently re-

typically set by organizations, public and private, non-profit fined to be fully testable. Hopefully, passage of an adequate

438 AJPH May, 1976, Vol. 66, No. 5

FRAMEWORK FOR PREVENTION

National Health Education and Promotion Act will make rise in death rates for 15-24 year-olds, Soc. Sc. and Med. 9:383-

possible the development and testing of such models in order 96, 1975.

to help health professionals and consumers focus effectively 19. Milio, N., Organization and Power: The Israeli Kibbutz and Chi-

nese Commune. A Comparative Study in Social Organization

on the prevention of disease rather than on its repair or con- (unpub. manuscript), Yale University Departments of Sociolo-

tainment. gy and Far Eastern Studies, May, 1969.

20. Milio, N., Co-mingling rings: can organizations become self-re-

newing? Intention: A J. of Alternative Institutions, June, 1971.

21. Terrill, R., The 800,000: The Real China, Boston: Atlantic-

REFERENCES Little-Brown Books, 1972.

1. Freymann, J., Medicine's great schism: prevention vs. cure: an 22. Newell, K., Ed. Health by the People, Geneva: WHO, 1975.

historical interpretation". Med. Care, 13:525-36, 1975. 23. Stycos, J. M., The Clinic and Information Flow, Ithaca, N.Y.:

2. Powles, J., On the limitations of modem medicine. Science, Cornell Univ., 1974.

Medicine and Society, 1:1-30, 1973. 24. Coburn, D., and Pope, C., Socioeconomic status and preventive

3. McKeown, T., et al, An interpretation of the modem rise of pop- health behavior, J. Health and Social Behavior, 15:67-78, 1974.

ulation in Europe. Population Studies, 26:345-83, 1972. 25. Steele, J., and McBroom, W., Conceptual and empirical dimen-

4. Illich, I., Medical Nemesis, London: Calder & Boyars, 1975. sions of health behavior, J. Health and Social Behavior, 13:382-

5. Carlson, R., The End of Medicine, New York: Wiley, 1975. 92, 1972.

6. Screening for Disease (series) Lancet. Oct. 5 through Dec. 14, 26. Farquhar, J., Interdisciplinary approaches to heart disease pre-

1974. vention inclusion, Hearings, op. cit.

7. Cochrane, A. L., Effectiveness and Efficiency, London: Nuf- 27. Green, L., Diffusion and adoption of innovations related to car-

field Provincial Hosp. Trust, 1972. diovascular risk behavior in the public, report included in Hear-

8. Minister of National Health and Welfare, A New Perspective on ings, op. cit.

the Health of Canadians: A Working Document, Ottawa: Govt. 28. Pomerlau, O., et al., Role of behavior modification in pre-

of Canada, 1974. ventive medicine, N. Eng. J. Med. 292:1277-82, 1975.

9. U.S. Senate, Hearings on National Health Promotion and Educa- 29. Maccoby, N., Achieving behavior change via mass media and

tion 1975, Subcomm. on Health, May 7-8, 1975, Wash., D.C. interpersonal communication, in Hearings, op. cit.

Senate-passed S. 1467 30. Institute for Communications Research, Annual Report 1973-

10. Task Force Reports for the National Conference on Preventive 74, Calif.: Stanford Univ., Oct., 1974.

Medicine, inclusions in Hearings, op. cit. 31. Rosenberg, S., A Case for Patient Education, Hospital Formu-

11. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics lary Management, 6:1-4, 1971.

Series from the ongoing Health Interview Survey, the Health 32. Toward a National Policy of Health Promotion and Consumer

Examination Survey, Health and Nutrition Survey, National Health Education, Task Force Report IV National Conference

High Blood Pressure Survey, Rockville, MD: HEW, Health Re- on Preventive Medicine, June 9-11, 1975, Wash., D.C.

sources Administration, 1973. 33. Simmons, J., Ed. Making Health Education Work, AJPH

12. Milio, N., et al., Simiplified Primary Care Data Guide (in prepa- (suppl.) 65: Oct., 1975.

ration). 34. APHA Committee on Educational Tasks in Chronic Illness, A

13. Milio, N., The Care of Health in Communities: Access for Out- Model for Planning Patient Education, Wash., D.C.: NIH, Oct.,

casts, New York: Macmillan, 1975. 1970.

14. Puffer, R., and Serrano, V., Patterns of Mortality in Childhood, 35. Kucha, D., Guidelines for Implementing An Ambulatory Con-

D.C.: Pan Am. Health Org., 1973. sumer Health Information System: A Handbook for Health Edu-

15. Hinkle, L., Ecological observations of the relation of physical cation, Texas: U.S. Army-Baylor University Graduate

illness, mental illness, and the social environment, Psychosom. Research Series, 1973.

Med. 23:289-97, 1961. 36. Young, M., Review of research and studies related to health

16. Cairns, J., The cancer problem, Scient. Am. Nov., 1975. education practice, Health Education Monographs series in

17. Moss, G., Illness, Immunity, and Social Interaction: The Dy- vols. 23-28, 1967-69.

namics of Biosocial Resonation, New York: Wiley, 1973, Chap- 37. Green, L., and Figa-Talamanca, I., Suggested designs for eval-

ter 3. uation of patient education programs, Health Education Mono-

18. Waldron, I., and Eyer, J., Socioeconomic causes of the recent graphs, 2:54-71, 1974.

AJPH May, 1976, Vol. 66, No. 5 439

You might also like

- Milio's Framework for Community Health Nursing and PreventionDocument50 pagesMilio's Framework for Community Health Nursing and PreventionLeya Thaobunyuen100% (1)

- Ethical Issues in Obesity InterventionsDocument4 pagesEthical Issues in Obesity InterventionsAle Mujica Rodríguez100% (1)

- Public Health Group AssignmentDocument7 pagesPublic Health Group AssignmentNANNYONGA OLGANo ratings yet

- Ética Na ObesidadeDocument4 pagesÉtica Na ObesidadeELISANGELA FORESTIERINo ratings yet

- CHN-2-LECTUREDocument44 pagesCHN-2-LECTUREandrea.maungca.mnlNo ratings yet

- Establishing a Culture of Patient Safety: Improving Communication, Building Relationships, and Using Quality ToolsFrom EverandEstablishing a Culture of Patient Safety: Improving Communication, Building Relationships, and Using Quality ToolsNo ratings yet

- The Corporatization of American Health Care: The Rise of Corporate Hegemony and the Loss of Professional AutonomyFrom EverandThe Corporatization of American Health Care: The Rise of Corporate Hegemony and the Loss of Professional AutonomyNo ratings yet

- CHN Key Concepts Definitions ModelsDocument7 pagesCHN Key Concepts Definitions ModelsArlene LabuguenNo ratings yet

- How Not to Die: The Code to Your Amazing Life, Living Longer, Safer, and HealthierFrom EverandHow Not to Die: The Code to Your Amazing Life, Living Longer, Safer, and HealthierNo ratings yet

- La Dieta Mediterranea (Psycologia y Ntrucion) PDFDocument15 pagesLa Dieta Mediterranea (Psycologia y Ntrucion) PDFAle De La FuenteNo ratings yet

- Milios Framework For PreventionDocument16 pagesMilios Framework For PreventionVIVIEN CONSIGNANo ratings yet

- Community Health: A Guide to Major Concepts and ToolsDocument29 pagesCommunity Health: A Guide to Major Concepts and ToolsMa Cecelia PalmeroNo ratings yet

- Hapl04 Nutpob Docrelac Jacoby EngDocument4 pagesHapl04 Nutpob Docrelac Jacoby EngRosmira Agreda CabreraNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Public HealthDocument312 pagesEvidence-Based Public HealthBudi Lamaka100% (7)

- CHN Mod 1Document5 pagesCHN Mod 1Monlexter MewagNo ratings yet

- Public Health Dissertation TitlesDocument7 pagesPublic Health Dissertation TitlesWriteMyPaperPleaseSingapore100% (1)

- The Demand For Health Theory and Applications PDFDocument12 pagesThe Demand For Health Theory and Applications PDFCarol SantosNo ratings yet

- Health Reform without Side Effects: Making Markets Work for Individual Health InsuranceFrom EverandHealth Reform without Side Effects: Making Markets Work for Individual Health InsuranceNo ratings yet

- Healthy Public Policy AdvocacyDocument3 pagesHealthy Public Policy AdvocacyLuo MiyandaNo ratings yet

- What's In, What's Out: Designing Benefits for Universal Health CoverageFrom EverandWhat's In, What's Out: Designing Benefits for Universal Health CoverageNo ratings yet

- Health 499 Senior Capstone Artifact 2 ReflectionDocument4 pagesHealth 499 Senior Capstone Artifact 2 Reflectionapi-622203747No ratings yet

- Jonas, Waine B. - Manual de Terapias AlternativasDocument348 pagesJonas, Waine B. - Manual de Terapias AlternativaspauloadrianoNo ratings yet

- Public Health Perspectives on Disability: Science, Social Justice, Ethics, and BeyondFrom EverandPublic Health Perspectives on Disability: Science, Social Justice, Ethics, and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: An Introduction To Public HealthDocument22 pagesChapter Three: An Introduction To Public HealthИскен АдылбековNo ratings yet

- Law As A Tool To Facilitate Healthier Lifestyles and Prevent ObesDocument5 pagesLaw As A Tool To Facilitate Healthier Lifestyles and Prevent ObesAnisha Agirivina PohanNo ratings yet

- Food & Your Health: Selected Articles from Consumers' Research MagazineFrom EverandFood & Your Health: Selected Articles from Consumers' Research MagazineNo ratings yet

- Ethical Analysis in Public Health: Department of EthicsDocument5 pagesEthical Analysis in Public Health: Department of Ethicsworopom8856No ratings yet

- Module One: Concepts, Principles and Appreoaches of Public HealthDocument9 pagesModule One: Concepts, Principles and Appreoaches of Public HealthFelix KimothoNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Community Health and EpidemiologyDocument35 pagesIntroduction to Community Health and EpidemiologyMark Johnson Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Health A Fundamental Right2Document47 pagesHealth A Fundamental Right2Parthik SojitraNo ratings yet

- Intro To PHPDocument18 pagesIntro To PHPHajra MirzaNo ratings yet

- Self-Empowerment in Health PromotionDocument7 pagesSelf-Empowerment in Health PromotionRob21aNo ratings yet

- Genetically Altered Foods and Your Health: Food at RiskFrom EverandGenetically Altered Foods and Your Health: Food at RiskRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Perspective Mexico's Experience in Building a Toolkit for Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases Prevention - Rivera 2024 Perspective Mexicos experience_Document9 pagesPerspective Mexico's Experience in Building a Toolkit for Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases Prevention - Rivera 2024 Perspective Mexicos experience_SUSANA PEREZ CUTIÑONo ratings yet

- Equity in Healthcare: Journal of the Student National Medical Association (JSNMA), #22.1From EverandEquity in Healthcare: Journal of the Student National Medical Association (JSNMA), #22.1No ratings yet

- Community & Public Health: Course TittleDocument11 pagesCommunity & Public Health: Course TittleAesthetics MinNo ratings yet

- DYNCM113:: (Population Groups and Community As Clients)Document13 pagesDYNCM113:: (Population Groups and Community As Clients)Irish Jane GalloNo ratings yet

- Public Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandPublic Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Anti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIIFrom EverandAnti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIINo ratings yet

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument3 pagesTheoretical FrameworkLinus Dewey100% (1)

- TOPIC 1 - What Is Public HealthDocument12 pagesTOPIC 1 - What Is Public HealthDebbie Iya Telacas BajentingNo ratings yet

- Combined ReadingsDocument137 pagesCombined Readingsfaustina lim shu enNo ratings yet

- An Ecological Perspective On Health Promotion ProgramsDocument27 pagesAn Ecological Perspective On Health Promotion ProgramsDaniel MesaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XVIIFrom EverandAnti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XVIIRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Risky Medicine: Our Quest to Cure Fear and UncertaintyFrom EverandRisky Medicine: Our Quest to Cure Fear and UncertaintyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- CHN-WEEK-1-SY-2022Document54 pagesCHN-WEEK-1-SY-2022Moon KillerNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Public HealthDocument312 pagesEvidence-Based Public Healthnaravichandran3662100% (1)

- The Cult and Science of Public Health: A Sociological InvestigationFrom EverandThe Cult and Science of Public Health: A Sociological InvestigationNo ratings yet

- Health Eco ModuleDocument4 pagesHealth Eco ModuleRenaNo ratings yet

- Evidence About Health Literacy and Health OutcomesDocument4 pagesEvidence About Health Literacy and Health OutcomesukhtianitaNo ratings yet

- Yale: Hiscock Health, IRA VDocument9 pagesYale: Hiscock Health, IRA VKay KhineNo ratings yet

- Humanising Healthcare: Patterns of Hope for a System Under StrainFrom EverandHumanising Healthcare: Patterns of Hope for a System Under StrainRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- TUIL 4 - Ivan Wima Aditama - 20548 - 05 PDFDocument6 pagesTUIL 4 - Ivan Wima Aditama - 20548 - 05 PDFIvan Wima AditamaNo ratings yet

- Child Sexual Abuse: Current Evidence, Clinical Practice, and Policy DirectionsFrom EverandChild Sexual Abuse: Current Evidence, Clinical Practice, and Policy DirectionsNo ratings yet

- Essay 1Document1 pageEssay 1Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Essay 3Document2 pagesEssay 3Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Yw 1Document1 pageYw 1Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Essay 5Document2 pagesEssay 5Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Essay 0Document2 pagesEssay 0Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- The Following Questions Apply To The Scenario GivenDocument3 pagesThe Following Questions Apply To The Scenario GivenLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Name: - Caring For A Patient On Isolation PrecautionDocument5 pagesName: - Caring For A Patient On Isolation PrecautionLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Embracing Evolution (AutoRecovered)Document3 pagesEmbracing Evolution (AutoRecovered)Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- There Are Three Elements Needed To Make A ManDocument1 pageThere Are Three Elements Needed To Make A ManLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- AsdasdasDocument1 pageAsdasdasLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument2 pagesCase AnalysisLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- First Major Advantage Offered by Internet Marketing To Both Business Organizations and Consumers Is Having Global AccessDocument2 pagesFirst Major Advantage Offered by Internet Marketing To Both Business Organizations and Consumers Is Having Global AccessLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT CHILDDocument5 pagesPHYSICAL ASSESSMENT CHILDLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- On Waste Management / Green Day Project (WM/GDP) : Community Needs AssessmentDocument4 pagesOn Waste Management / Green Day Project (WM/GDP) : Community Needs AssessmentLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Embracing Evolution (AutoRecovered)Document3 pagesEmbracing Evolution (AutoRecovered)Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Placenta Previa and Abruptio Placenta Risks and SymptomsDocument3 pagesPlacenta Previa and Abruptio Placenta Risks and SymptomsLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

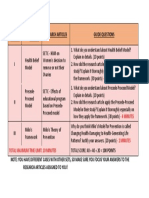

- Set E Test No. Theoretical Models Research Articles Guide QuestionsDocument1 pageSet E Test No. Theoretical Models Research Articles Guide QuestionsLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- God's revelation in the Old Testament and BibleDocument1 pageGod's revelation in the Old Testament and BibleLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- DsadDocument4 pagesDsadLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- The Health Belief Model Is A Theoretical Framework For Guiding Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Measures in Public HealthDocument3 pagesThe Health Belief Model Is A Theoretical Framework For Guiding Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Measures in Public HealthLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- SAD - Source of MoralityDocument1 pageSAD - Source of MoralityLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Ukraine FinalDocument62 pagesUkraine FinalLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Inflation Differentials Between Austria, The Euro Area, Germany and ItalyDocument12 pagesInflation Differentials Between Austria, The Euro Area, Germany and ItalyLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- INFLATION ANALYSIS MacroeconomicsDocument2 pagesINFLATION ANALYSIS MacroeconomicsLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Community Health Nursing PDFDocument43 pagesCommunity Health Nursing PDFElay PedrosoNo ratings yet

- INFLATION ANALYSIS Macroeconomics Final 1Document2 pagesINFLATION ANALYSIS Macroeconomics Final 1Larr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Philippines FinalDocument36 pagesPhilippines FinalLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Activity Design MakinsgDocument5 pagesActivity Design MakinsgLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Infection Prevention and Control Prsactices 1570477491 PDFDocument29 pagesInfection Prevention and Control Prsactices 1570477491 PDFLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- Chiropractic & OsteopathyDocument11 pagesChiropractic & OsteopathyLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- CHPTR 2 BOMDocument9 pagesCHPTR 2 BOMpoorohitNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Politics and Society: Agents and Nature of Political SocializationDocument6 pagesCaribbean Politics and Society: Agents and Nature of Political SocializationCheolyn SealyNo ratings yet

- A Marketing Mix Model For A Complex and Turbulent EnvironmentDocument19 pagesA Marketing Mix Model For A Complex and Turbulent EnvironmentBelaynehYitayewNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Consumer Behaviour Regarding Various Telecom CompaniesDocument75 pagesA Project Report On Consumer Behaviour Regarding Various Telecom CompaniesAbhinäv DängNo ratings yet

- Product RecallDocument9 pagesProduct Recallgeeta_sharma_844458100% (1)

- An Evaluation of The Effects of Matched Stimuli On Behaviors Maintained by Automatic ReinforcementDocument16 pagesAn Evaluation of The Effects of Matched Stimuli On Behaviors Maintained by Automatic ReinforcementAlexandra AddaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior ModelDocument12 pagesConsumer Behavior Modelmira chehabNo ratings yet

- What Is Consumer BehaviorDocument27 pagesWhat Is Consumer BehaviorDilini IndeewariNo ratings yet

- An Outline of Social PsychologyDocument426 pagesAn Outline of Social PsychologyAlejandro CalocaNo ratings yet

- A Study To Assess The Role of Sensory Marketing in Luxury RestaurantsDocument57 pagesA Study To Assess The Role of Sensory Marketing in Luxury RestaurantsVikram Fernandez33% (3)

- Theories and ApproachesDocument13 pagesTheories and ApproachesPrince Rupee GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Managing School Canteen Along With The Behaviour of Student CustomersDocument16 pagesManaging School Canteen Along With The Behaviour of Student CustomersLeo Sandy Ambe CuisNo ratings yet

- CASAGRA Transformative Leadership Model by Sr. Carol Agravante & Composure Behavior and Patient's Wellness Outcome Model by Carmelita DivingraciaDocument2 pagesCASAGRA Transformative Leadership Model by Sr. Carol Agravante & Composure Behavior and Patient's Wellness Outcome Model by Carmelita DivingraciaJhunmae KindipanNo ratings yet

- Values of NursingDocument27 pagesValues of NursingJay-l Escuadra82% (22)

- Heiner (1983)Document37 pagesHeiner (1983)Renato Cardoso BottoNo ratings yet

- Changing Health Behaviour PDFDocument33 pagesChanging Health Behaviour PDFvpapaefNo ratings yet

- The Essence by Michael BrownDocument59 pagesThe Essence by Michael BrownBilalNo ratings yet

- Communication Strategy UNESCO ForeignDocument28 pagesCommunication Strategy UNESCO Foreignsimrah zafarNo ratings yet

- BSCC 3-7Document5 pagesBSCC 3-7stella revai mugadzawetaNo ratings yet

- Example 3 (Science-Based)Document75 pagesExample 3 (Science-Based)poppygibson1111No ratings yet

- Etribalized MarketingDocument13 pagesEtribalized MarketingamazairaNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire On Consumer Buying Behaviour of Cosmetics PDFDocument15 pagesQuestionnaire On Consumer Buying Behaviour of Cosmetics PDFNishaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Theoretical FrameworksDocument35 pagesConsumer Behavior Theoretical FrameworksJohana ReyesNo ratings yet

- Tsl3109 PPG ModuleDocument145 pagesTsl3109 PPG ModuleEswari SangaralingamNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Public HealthDocument10 pagesIntroduction To Public HealthJames RiosaNo ratings yet

- A Report On The Impact of Inflation On The Marketing Strategies of McDonald and Its Consumer Decision MakingDocument16 pagesA Report On The Impact of Inflation On The Marketing Strategies of McDonald and Its Consumer Decision MakingOkikioluwa FajemirokunNo ratings yet

- Best Practices in Bank Customer Experience DesignDocument12 pagesBest Practices in Bank Customer Experience DesignEric Larse100% (1)

- Marketing Mix in E-Commerce Purchasing Decisions: Lathifah Nur ShoimahDocument8 pagesMarketing Mix in E-Commerce Purchasing Decisions: Lathifah Nur Shoimahdevana anishaNo ratings yet

- 5TeamScape Twoday WorkshopDocument32 pages5TeamScape Twoday WorkshopMaha KhanNo ratings yet

- Fuba-Bip-Data CollectionDocument8 pagesFuba-Bip-Data Collectionapi-296414448No ratings yet