Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Loopholes Orientalism

Uploaded by

Ruqiya KhanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Loopholes Orientalism

Uploaded by

Ruqiya KhanCopyright:

Available Formats

Wesleyan University

Shades of Orientalism: Paradoxes and Problems in Indian Historiography

Author(s): Peter Heehs

Source: History and Theory, Vol. 42, No. 2 (May, 2003), pp. 169-195

Published by: Wiley for Wesleyan University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3590880 .

Accessed: 21/06/2014 19:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and Wesleyan University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History

and Theory.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

History and Theory42 (May 2003), 169-195 ? Wesleyan University 2003 ISSN: 0018-2656

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM:PARADOXESAND PROBLEMS

IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY'

PETERHEEHS

ABSTRACT

In Orientalism,EdwardSaid attemptsto show thatall Europeandiscourseaboutthe Orient

is the same, and all Europeanscholars of the Orientcomplicit in the aims of European

imperialism.Theremay be "manifest"differencesin discourse,but the underlying"latent"

orientalismis "moreor less constant."This does not do justice to the markeddifferences

in approach,attitude,presentation,and conclusions found in the works of various orien-

talists. I distinguishsix differentstyles of colonial and postcolonial discourse about India

(heuristiccategories,not essential types), and note the existence of numerousprecolonial

discourses. I then examine the multiple ways exponents of these styles interactwith one

anotherby focusing on the early-twentieth-centurynationalistorientalist,Sri Aurobindo.

Aurobindo'sthoughttook form in a colonial frameworkand has been used in variousways

by postcolonial writers. An anti-Britishnationalist, he was by no means complicit in

British imperialism.Neither can it be said, as some Saidiansdo, thatthe nationaliststyle

of orientalism was just an imitative indigenous reversal of European discourse, using

terms like "Hinduism" that had been invented by Europeans. Five problems that

Aurobindodealt with are still of interest to historians:the significance of the Vedas, the

date of the vedic texts, the Aryaninvasion theory,the Aryan-Dravidiandistinction,andthe

idea that spiritualityis the essence of India.His views on these topics have been criticized

by Leftist and Saidian orientalists,and appropriatedby reactionary"Hindutva"writers.

Such critics concentrateon that portion of Aurobindo'swork which stands in opposition

to or supportstheirown views. A more balancedapproachto the nationalistorientalismof

Aurobindoand otherswould take accountof theirreligious and political assumptions,but

view theirprojectas an attemptto create an alternativelanguageof discourse.Althoughin

need of criticism in the light of modem scholarship,their work offers a way to recognize

culturalparticularitywhile keeping the channels of interculturaldialogue open.

I. INTRODUCTION

Now that "orientalism"has become an academicbuzzword, it may be useful to

recall its formermeanings. From the mid-eighteenthto the late-twentiethcentu-

ry, the term was applied to the study of the languages, literatures, and cultures of

the Orient. In his 1978 book Orientalism, Edward Said acknowledges this ordi-

nary (but by then obsolete) meaning and adds two others: "a style of thought

based upon an ontological and epistemological distinction made between 'the

1. I amgratefulto the membersof the ReligionsReformMovementpanelat the 17thEuropean

Conferenceon ModemSouthAsianStudies,Heidelberg, 2002;to BrianFayandtheother

September

editors of History and Theory;to JacquesPouchepadass;and to two anonymousreviewers for their

commentsandsuggestions.Finalresponsibility

is, of course,my own.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

170 PETERHEEHS

Orient'and (most of the time) 'the Occident' " and "a Western style for domi-

nating, restructuring,and having authorityover the Orient."2It is with the third

sort of orientalismthat Said chiefly is concerned."Orientalism"in this sense is a

discourse about the Orient as the "other"of Europe, which confirms Europe's

dominantposition. Said studies the works of scholars who instantiatethis dis-

course but he is less concerned with particularindividualsthan with the body of

European discursive practices in regard to "the Orient" that generate a self-

affirmingaccount of what it is (essentially inferiorto Europe, and so on).3 One

of his more controversialcontentionsis that all Europeanorientalistsof the colo-

nial period were consciously or unconsciously complicitin the aims of European

colonialism.4

Said's theoryhas been criticizedby scholarswho study orientalcultures-now

referredto as Indologists, Sinologists, Asian Studies specialists, and so forth-

on several counts. Many object to his indiscriminatelumping togetherof differ-

ent types of orientalism.Denis Vidal, for instance, insists that colonial oriental-

ism of the nineteenthcenturyand the sort of orientalismhighlighted by Said are

"two entirely different things." The orientalism of the nineteenthcentury itself

had two sides, one scholastic, the other romantic,and "Said's definitionscannot

account for" this distinction.5Thomas Trautmannremindsus that British cham-

pions of Indian languages and culture (called "Orientalists")were opposed by

government proponents of English education (called "Anglicists"), and notes

that"the Saidianexpansion of Orientalism,applied in this context, tends to sow

confusion where there was once clarity."6David Luddendistinguishes"colonial

knowledge," which generated authoritativefacts about colonized people, from

otherforms of orientalism,some of which were explicitly anticolonial.7Rosane

Rocher spells out the consequences of these conflations:"Said's sweeping and

passionate indictmentof orientalistscholarshipas part and parcel of an imperi-

alist, subjugatingenterprisedoes to orientalist scholarshipwhat he accuses ori-

entalist scholarshipof having done to the countries east of Europe; it creates a

single discourse, undifferentiatedin space and time and across political, social

2. Edward W. Said, Orientalism: WesternConceptions of the Orient (London: Penguin Books,

1991), 3-4.

3. See, for example, ibid., 94.

4. See, for example, ibid., 203-204: "Forany Europeanduringthe nineteenthcentury-and I think

one can say this almost without qualification- Orientalism was such a system of truths, truths in

Nietzsche's sense of the word. It is thereforecorrectthat every European,in what he could say about

the Orient, was consequently a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric .... My con-

tention is that Orientalismis fundamentallya political doctrine willed over the Orient because the

Orientwas weaker than the West."

5. Denis Vidal, "Max Miiller and the Theosophists:The OtherHalf of VictorianOrientalism,"in

Jackie Assayag et al., Orientalismand Anthropology:From Max Miiller to Louis Dumont (Pondi-

cherry,India:InstitutFranqaisde Pondichdry,1997), 14-15.

6. Thomas R. Trautmann,Aryans and British India (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of

California Press, 1997), 23. This point was made earlier by David Kopf in "Hermeneuticsversus

History,"Journal of Asian Studies 39 (1980), 495-506.

7. David Ludden, "Orientalist Empiricism: Transformations of Colonial Knowledge," in

Orientalismand the Postcolonial Predicament:Perspectives on South Asia, ed. Carol A. Brecken-

ridge and Peter van der Veer (Philadelphia:University of PennsylvaniaPress, 1993), 252.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 171

and intellectual identities."8The irony is that the Saidian analysis of orientalist

discourse is itself an orientalist discourse-one that "sometimes appears to

mimic the essentializing discourse it attacks,"as James Clifford puts it.9 This

essentializing of orientalistscholarshipmight be excused if it resulted in a trans-

formed view of oriental and occidental societies. But to Said the Occident is

always the dominantpartner,determiningthe terms of the oriental response.As

a result the very orientals who are meant to be the beneficiariesof the Saidian

analysis are again denied agency and voice.10

At one point in his presentation,Said does distinguishbetween what he calls

latent orientalism,"an almost unconscious (and certainlyan untouchable)posi-

tivity" of ideas about the Orient, and manifest orientalism,"the various stated

views about Oriental society, languages, literatures,history, sociology, and so

forth."This allows him to acknowledgethe possibility of varying expressions of

orientalismwhile retaining his core concept. For, he asserts, "whateverchange

occurs in knowledge of the Orient is found almost exclusively in manifest

Orientalism;the unanimity,stability,and durabilityof latentorientalismis more

or less constant.""1 The changes in the forms of manifest orientalismare frothon

the surface;the underlyingtruthof latentorientalismis the same. If this is so, the

paradoxremains.The concept on which Said and his epigones base theircritique

of the essentializing of "the Orient"is itself an essential category.

Despite the criticisms leveled against Said by specialists in the literaturethat

compriseshis material,his theoryhas gained currencyboth inside and outsidethe

academy,with the result that "orientalism"is now appliedloosely to any unflat-

tering Westernattitudeabout the East. In what follows I returnto scholarlydis-

course properlyspeaking.Acknowledgingthe utility of Said's "orientalism"as a

criticaltool, I enlarge and historicize the concept by examining various forms of

orientalknowledge. Said's areaof interestwas Middle Easternorientalism;I con-

fine myself to Indian. I begin by distinguishing six "styles" of orientalistdis-

course about India. These, it should be clearly understood,are heuristic cate-

gories, not essential types. Three belong to the colonial, three to the postcolonial

8. Rosane Rocher, "BritishOrientalismin the EighteenthCentury:The Dialectics of Knowledge

and Government," in Breckenridge and van der Veer, eds., Orientalism and the Postcolonial

Predicament,215.

9. James Clifford, review-essay of Said's Orientalism,History and Theory 19 (1980), 210. The

same point is made by, among others,Albert Hourani,"The Road to Morocco,"New YorkReview of

Books (8 March 1979), page 5 of online edition;Arif Dirlik, "The Postcolonial Aura: Third World

Criticismin the Age of Global Capitalism,"CriticalInquiry20 (Winter1994), 344; CharlesHallisey,

"RoadsTakenand Not Takenin the Study of TheravadaBuddhism,"in Curatorsof the Buddha:The

Study of Buddhism under Colonialism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 32; Fred

Dallmayr, Beyond Orientalism:Essays on Cross-CulturalEncounter (Albany: State University of

New YorkPress, 1996), 118; William R. Pinch, "Same Difference in Indiaand Europe,"History and

Theory38 (October 1999), 389-407; RichardM. Eaton, "(Re)imag(in)ingOther2ness:A Postmortem

for the Postmodernin India,"Journal of WorldHistory 11 (2000), 69-71.

10. This paradox has been noted by Hallisey, "Roads Taken and Not Taken," 32; Eaton,

"(Re)imag(in)ingOther2ness,"65-66; Wendy Doniger, " 'I Have Scinde': Flogging a Dead (White

Male Orientalist)Horse,"Journal of Asian Studies 58 (November 1999), 945; and others.

11. Said, Orientalism,206.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

172 PETER

HEEHS

era.12There were also, of course, numerousindigenous discourses about what

Europeanscall "the Orient"in precolonialtimes.

Limitations of space prevent me from doing more than identifying typical

exponentsof each style and citing illustrativepassages. This shouldbe enough to

serve my immediatepurpose,which is to show that thereare many shades of ori-

entalism.The next step is to show thatthe exponents of these styles interactwith

one anotherin various ways. I accomplish this by examiningthe life and works

of the nationalistorientalistSri Aurobindo,showing how his approachtook form

in the matrix of colonial orientalismand has been criticized or appropriatedby

postcolonial orientalists of various sorts. Such scholars stress Aurobindo's

nationalisticpremises but miss the broaderimportof his arguments.The value of

his work and the work of other scholarsof the Orientdepends more on the qual-

ity of their scholarshipthan on their political or religious assumptions.

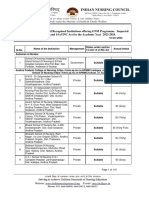

Styles of OrientalistDiscourse

Era Style Approx.period Examples

Precolonial 0 various] IBefore 1750 IKamikagama(?seventhcent.)

Colonial 1 Patronizing/ 1750-1947 (and Jones, Institutesof HinduLaw

Patronized after) or the Ordinancesof Menu

(1794);Rammohun

Roy,

Translationof an Abridgement

of theVedant(1816)

2 Romantic 1800-1947 (and F. Schlegel, liber die Sprache

after und Weisheitder Indier (1808);

Sarda,HinduSuperiority

(1906)

3 Nationalist 1850-1947 (and Nivedita,AggressiveHinduism

after) (1905); Aurobindo,A Defence

of Indian Culture(1918-1921)

Postcolonial 4 Critical 1947 to present Thapar,InterpretingEarly

India(1993);Trautmann,

Aryansand BritishIndia

(1997)

5 Reductive 1978 to present Inden,ImaginingIndia (1990);

Chatterjeeet al., Textsof Power

(1995)

6 Reactionary c.1980 to pres- Rajaramand Frawley,Vedic

ent Aryansand the Originsof

Civilisation(1995)

12.HereandelsewhereI use"postcolonial" in its unadorned

sense:"belonging

to theperiodafter

thecolonialperiod,"thatis, withregardto India,"post-1947."

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 173

Precolonial Discourses

If the Europeanidea of the Orientis a Europeaninvention,the Orientitself is not.

Even Said is obliged to "acknowledgeit tacitly."13Long before Vasco da Gama

landed in Calicut in 1498, the peoples of SouthAsia created modes of self- and

world-representationthat owe nothing to Europeannotions. (It is necessary to

mention this obvious fact, since reductive orientalists who push theory to

extremesare sometimes inclined to forget it.) Many of these systems of discourse

are preservedin texts or methods of practiceor both. One example (among hun-

dreds) is the Shaiva Siddhantaschool of early medieval India, whose rituals are

still performedin south India.The Kamikagama(?seventh centuryCE)and relat-

ed texts presenta systematic and coherentview of the Divine, the world, and the

human being, and detail practices that "not only sought to bring the agent per-

sonally into relationwith God and to transformhis or her condition,but ... also

collectively engendered the relations of community, authority,and hierarchy

within human society."14Far from being influencedby Westerndiscourse, such

precolonial societies were oblivious of it. "There is," as intellectual historian

Wilhelm Halbfass writes, "no sign of active theoretical interest, no attemptto

respond to the foreign challenge, to enter into a 'dialogue'--up to the period

around 1800."15

ThreeStyles of Colonial Orientalism

1. Patronizing/PatronizedOrientalism. European visitors to India between

1500 and 1750 published their observations in travel narratives, missionary

polemic, and so on, but serious Europeanoriental scholarship may be said to

begin towardsthe end of the eighteenth century.Two landmarksare the forma-

tion of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta in 1784 and the publication of Charles

Wilkins'stranslationof the Bhagavad Gita the following year.The prefaceto this

volume by Governor-GeneralWarrenHastings contains a passage that is arche-

typally "orientalist"in the Saidian sense: "Every accumulationof knowledge,

and especially such as is obtained by social communicationwith people over

whom we exercise a dominion founded on the right of conquest, is useful to the

state."But Hastingsalso demonstratesa real, thoughpatronizing,appreciationof

Hinduculture.He notes, for instance,thatthe Brahmins'"collective studies have

led them to the discovery of new tracks and combinationsof sentiment,totally

13. Said, Orientalism,5.

14. Richard H. Davis, Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: WorshippingSiva in Medieval India

(Princeton:PrincetonUniversity Press, 1991), 6.

15. WilhelmHalbfass,India and Europe:An Essay in Philosophical Understanding(Albany:State

University of New York Press, 1988), 437. Halbfass's statementis a generalizationand can pass as

such, thoughI would move the date backto 1750 or earlier.Workssuch as Mirza ShahI'Tesamuddin's

account in Persian of his trip to England in 1765 (translatedby Kaiser Haq and published as The

Wondersof Vilayat[Leeds:Peepal Books, 2002]), and AnandaRanga Pillai's diariesin Tamil,dealing

with official and private life in French Pondicherrybetween 1736 and 1761 (The Private Diary of

AnandaRangaPillai, ed. J. FrederickPrice [reprintedition,Delhi:Asian EducationalServices, 1985]),

show thateighteenth-centuryIndianswere as capableof observingand theorizingaboutEuropeansas

Europeanswere of them. One might even go back as far as the late sixteenth century,when the emp-

erorAkbar(1542-1605), always curiousin mattersof religion, interactedwith Jesuitsfrom Goa.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

174 PETERHEEHS

differentfrom the doctrineswith which the learnedof other nations are acquaint-

ed: doctrines,which ... may be equally foundedin truthwith the most simple of

our own."16In a similar vein, the iconic orientalistWilliam Jones writes in the

preface to his translationof the Manu Smriti that this code is "revered,as the

word of the Most High, by nations of great importanceto the political and com-

mercial interests of Europe," who ask only protection,justice, religious toler-

ance, and "the benefit of those laws, which they have been taught to believe

sacred, and which alone they can possibly comprehend."17With British rule

established,patronizingEuropeanstaught their language to patronizedIndians,

some of whom made importantcontributionsto English-languagescholarship.

RammohunRoy (1772-1834), who produceda numberof translationsand expo-

sitions of Sanskrittexts, notes in the introductionto one that he had undertaken

the work "to prove to my Europeanfriends,thatthe superstitiouspracticeswhich

deform the Hindoo religion have nothing to do with the pure spirit of its dic-

tates!"18

2. Romantic Orientalism.British orientalism during the colonial period was

obviously connected, if not invariably complicit, with British imperialism.

Germanyhad nothingto do with imperialismin India,yet Germanytook the lead

in Sanskritstudies in the nineteenthcentury,a fact that impels Trautmannto ask:

"How does Said's thesis help us to understand"this?'19One of the first German

Sanskritistswas Friedrichvon Schlegel, whose Uber die Sprache und Weisheit

der Indier (1808) is a glorificationof the religion and philosophy of the "most

cultivatedand wisest people of antiquity."20 The work of Schlegel and otherori-

entalistshelped in the developmentof GermanRomanticism,of which Indophilia

was a major strand.Writerslike Goethe and Schopenhauerwere influencedby

Sanskrit literature,and published positive assessments that helped offset the

largely negative British view. Indian scholars were delighted to reproducesuch

Europeanpraise. Hindu Superiorityby Har Bilas Sarda(1906) is a catalogue of

out-of-contextencomiums by writersfrom Straboto PierreLoti, to which Sarda

addshis own obiter dicta, for example, "TheVedasare universallyadmittedto be

not only by far the most importantwork in the Sanskritlanguage but the greatest

work in all literature."21

3. Nationalist Orientalism.Towardsthe end of the nineteenthcentury,educat-

ed Indiansbegan turningfrom the imitativeAnglophilia of the previous genera-

tion to a renewed interest in their own traditions.Around the same time the

nationalmovementgot off to a slow start.In this climate a nationaliststyle of ori-

16. WarrenHastings, "To Nathaniel Smith, Esquire," in The Bhagavat-Geeta or Dialogues of

Kreeshnaand Arjoon, transl.CharlesWilkins (London: Printedfor C. Nourse, 1785), 13, 9.

17. William Jones, Institutes of Hindu Law: or, the Ordinances of Menu, in The Worksof Sir

WilliamJones, vol. 7 (London:Printedfor John Stockdale and John Walker, 1807), 89-90.

18. RammohunRoy, "Translationof an Abridgementof the Vedant,"in The Essential Writingsof

Raja RammohanRay, ed. Bruce Robertson(Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999), 3.

19. Trautmann,Aryans and British India, 22.

20. Schlegel, translatedin Halbfass, India and Europe, 76.

21. Har Bilas Sarda,Hindu Superiority:An Attemptto Determine the Position of the Hindu Race

in the Scale of Nations, 2d ed. (Ajmer:Scottish Mission IndustriesCompany, 1917), 177.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 175

entalism took root. SisterNivedita (MargaretE. Noble, 1867-1911), a disciple of

Swami Vivekananda(1863-1902), gives an explicitly nationalistic turn to her

writings on India. "Theland of the Vedasand of Jnana-Yogahas no right to sink

into the role of mere critic or imitator of European Letters," she writes in

Aggressive Hinduism."The Indianisingof India, the organising of our national

thought, the laying out of our line of march, all this is to be done by us, not by

others on our behalf."22Nivedita's friend Aurobindo Ghose (who became Sri

Aurobindo)insists even more firmly on the necessity of judging Indian culture

by Indianstandards.The career of this scholar,revolutionary,and mystic is dis-

cussed in some detail in section II.

ThreeStyles of Postcolonial Orientalism

4. Critical Orientalism. Nationalist scholarship was prominent during the

years of the freedom movement (1905-1947) and the first two decades after the

achievementof independence.During the 1950s and 1960s, historianstrainedin

Westernmethods and working within Westerntheoreticalframeworksbegan to

produce empirical studies of all periods of India's past. More recently, critical

scholarshiphas turnedits attentionto historiographicalissues. Romila Thapar,

for example, investigates how "boththe colonial experience and nationalismof

recent centuries influencedthe study,particularlyof the early period of [Indian]

history"in her InterpretingEarly India.23

5. Reductive Orientalism.As we have seen, Saidian interpretationsof orien-

talism and the Orient are themselves orientalist discourses.As Ludden puts it,

they inhabit "a place inside the history of orientalism."24Saidian treatmentsof

Indianhistory and culturebegan to appearwithin a decade of the publicationof

Orientalism.One of the first was Ronald Inden's ImaginingIndia (1990).25His

stated aim is to "makepossible studies of 'ancient' India that would restorethe

agency that those [Eurocentric]histories have strippedfrom its people and insti-

tutions."26But by insisting that EuropeanorientalistsconstructedHinduism,the

caste system, and so forth,27he tends instead to deny Indian agency and give a

new lease on life to Eurocentrism.

6. ReactionaryOrientalism.In recentyears a loose groupingof scholars,many

with degrees in scientific disciplines but without trainingin historiography,have

sought to restoreIndiato its ancientglory by rewritingits history.This revision-

ism is necessary because, "as a consequence of a centuryand a half of European

colonialism, and repeated extremely violent onslaughts [by Muslims and

Christians]going back nearly a thousandyears, Indianhistory and traditionhave

22. Sister Nivedita, Aggressive Hinduism, in The Complete Worksof Sister Nivedita (Calcutta:

Sister Nivedita Girls' School, 1973), vol. 3, 492, 500.

23. Romila Thapar, "Ideology and the Interpretationof Early Indian History" [1974], in

InterpretingEarly India (Delhi: Oxford UniversityPress, 1992), 1.

24. Ludden,"OrientalistEmpiricism,"271, emphasis mine.

25. Ronald Inden, Imagining India (Oxford:Basil Blackwell, 1990). The book was preceded by

Inden, "OrientalistConstructionsof India."ModernAsian Studies 20 (1986), 401-446.

26. Inden,ImaginingIndia, 1.

27. Ibid., 89, 49, 58, etc.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

176 PETERHEEHS

undergonegrievous distortionsand misinterpretations." This critiqueis directed

againstnineteenth-centuryEuropean orientalistsas well as contemporarywriters

who "assumedthatthe fashionabletheoriesof the age in which they were brought

up-theories like Marxism-represented universallaws of humanhistory."28

II. A BRITISH-TRAINEDINDIAN NATIONALIST

In my table, nationalistorientalismoccupies a pivotal place, midway between the

precolonialand early colonial discourseson one side and the three forms of post-

colonial practice on the other.In this section, I examine the life of a nationalist

writer,showing how his style of orientalismemergedin a scholarlyenvironment

dominatedby patronizingand romanticorientalistsand a political environment

in which loyalism and moderatedissent were giving way to extreme forms of

nationalism.Aurobindo Ghose (known as Sri Aurobindo, 1872-1950) is often

spoken of as a typical nationalist scholar, but his career was in some respects

unique.Raised in Englandwith no knowledge of the cultureof his homeland,he

was destinedfor a position in the colonial civil service but insteadbecame a rev-

olutionarypolitician. After a decade of literaryand political activity he retiredto

FrenchIndia to practiceyoga, embodying, in the eyes of his admirers,the spiri-

tual traditionthat, accordingto reductive orientalists,was an invention of colo-

nial orientalism.

Aurobindo's father was a British-trainedphysician who was active in local

government in Bengal. Frustratedin his attempts to enter the Indian Medical

Service and shuntedhere and there by the bureaucracy,he resolved that one or

more of his sons would become membersof the IndianCivil Service (ICS). Sent

to Englandat the age of seven, Aurobindowon scholarshipsto St. Paul's School,

London, and King's College, Cambridge,and passed the ICS entranceexamina-

tion in 1890. At Cambridgehe received a thoroughly"orientalist"introductionto

the culture of his homeland. He read about India's past in books like

Elphinstone's History of India and Mills's now-notorious History of British

India. He learned Bengali (the "mother-tongue"his father had forbidden him

from speaking) from an Englishman unable to read the novels of Bankim

ChandraChatterji.His teachers of Sanskritand Hindustanialso were European,

as was his lecturerin Hindu and Muslim law.29By the time he left Cambridgein

1892, his Greek and Latin were good enough to win prizes, but his Sanskritso

sketchy that when he first read the Upanishads,it was in the English translation

of the Oxford orientalistF. Max Miiller.

We get a glimpse of Aurobindo'sattitudetowardspatronizingorientalismin a

passage he wrote a decade later in reply to a passage in Miuller'spreface to the

SacredBooks of the East. "I confess it has been for many years a problemto me,

aye, and to a great extent is so still," Miillerwrote, "how the SacredBooks of the

28. NavaratnaS. Rajaramand David Frawley, VedicAryans and the Origins of Civilisation: A

Literaryand Scientific Perspective, 3d ed. (New Delhi: Voice of India, 2001), xv-xvi.

29. Final Examination of Candidates Selected in 1890 for the Civil Service of India (London:

Printedfor Her Majesty's StationeryOffice, 1892), 6, 10.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES

OFORIENTALISM 177

East should, by the side of so much that is fresh, natural,simple, beautiful, and

true, contain so much that is not only unmeaning, artificial and silly, but even

hideous and repellent."30Aurobindo'sreply was ironic in the great traditionof

British irony:

Now, I myselfbeingonly a poorcoarse-minded Orientalandthereforenot disposedto

denythegrossphysicalfactsof life andnature... amsomewhatat a loss to imaginewhat

theProfessorfoundin theUpanishads thatis hideousandrepellent.StillI was broughtup

almostfrommy infancyin Englandandreceivedan Englisheducation,so thatI have

glimmerings.But as to whathe intendsby the unmeaning,artificialandsilly elements,

therecanbe no doubt.Everythingis unmeaningin theUpanishads whichthe Europeans

cannotunderstand,everythingis artificialwhichdoes notcomewithinthecircleof their

mentalexperienceandeverythingis sillywhichis notexplicableby European scienceand

wisdom.31

In IndiaAurobindomasteredSanskritand Bengali and began to translatelit-

erary classics-the poems of Vidyapati, portions of the Mahabharata and

Ramayana, some works of Kalidasa-into elegant Victorian English. He also

wrote essays on various Sanskritauthors,in some of which he twitted the opin-

ions of European orientalists. "That accomplished scholar & litterateurProf

Wilson"-H. H. Wilson, first Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford-was,

Aurobindo noted around 1900, "at pains to inform" his readers that the mad

scene in Kalidasa'sVikramorvasiyam was nothingto the mad scene in King Lear,

but rather"a much tameraffairconformableto the mild, domestic & featureless

Hindu character& the feebler pitch of Hindu poetic genius. The good Professor

might have spared himself the trouble" since there was "no point of contact

between the two dramas."32 The Europeancondemnationof Indiandramaas sap-

less was "evidence not of a more vigorous critical mind but of a restrictedcriti-

cal sympathy.""The true spiritof criticism,"he concluded, "is to seek in a liter-

aturewhat we can find in it of great or beautiful,not to demand from it what it

does not seek to give us."33

Anotherhabit of Europeanscholarsthat got Aurobindo'shackles up was their

tendency to trace Indian achievementsback to European,usually Greek, prede-

cessors. Where Greek influence was evident, as in the Gandharanschool of

sculpture,he condemned the work as inferior to "pure"Indian styles. Europe's

literarycriteriawere not applicableto India.AlbrechtWeber'sidea that the orig-

inal Mahabharataconsisted only of the battle chapterswas a case of "arguing

from Homer."It was, he insisted, "not from European scholars that we must

expect a solution of the Mahabharataproblem,"since "they have no qualifica-

tions for the task except a power of indefatigableresearchand collocation .... It

30. F. Max Miiller,The Upanishads,PartI. VolumeI of TheSacredBooks of the East. Reprintedi-

tion (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass,1981), xii.

31. SriAurobindo,Kena and OtherUpanishads(Pondicherry:Sri AurobindoAshramTrust, 1972),

164.

32. Manuscript note included in Sri Aurobindo, Early Cultural Writings (Pondicherry: Sri

AurobindoAshramTrust,2003), 202.

33. Aurobindo,Early Cultural Writings,188-189.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

178 PETERHEEHS

is from Hindu [i.e. Indian] scholarshiprenovated & instructedby contact with

Europeanthat the attemptmust come."34

For all his condemnationof Europeanscholars,Aurobindoadmiredtheir tex-

tual scholarshipand made use of it in his own work. He wrote around1902 that

a student of Gaudapada's Karikas could not do better than to start with

"Deussen's System of the Vedantain one hand and any brief & popularexposi-

tion of the six Darshanas[philosophicalschools] in the other."35But he felt that

Europeanacademicscould not grasp the full meaning of Indian scriptures.This

was due to an essential differencein mentality:the Indianmind was "diffuseand

comprehensive,"able to acquire "a [deeper] and truerview of things in their

totality";the Europeanmind, "compact and precise," could hope only for "a

more accurateand practically serviceable conception of their parts."36Situated

between these two "minds,"he was in a position to mediate. His aim as a schol-

ar,as he saw it aroundthis time, was "to presentto Englandand throughEngland

to Europethe religious message of India."37

Aurobindo pursued this project between 1902 and 1906 in a series of com-

mentarieson the Upanishads.Then, between 1906 and 1910, he put most of his

energy into the nationalistmovement and its revolutionaryoffshoot. (His trans-

formationfrom quiet scholar to fiery patriotwas much remarkedon at the time.

After his arrestfor conspiracyto wage war againstthe King, a formerICS class-

matewrote:"FancyGhose a raggedrevolutionary!He could with far greaterease

write a lexicon or compose a noble epic").38During these years he managedto

complete a few "patriotic"translations;but it was not until he retiredfrom poli-

tics and settled in French Pondicherryin 1910 that he found time to fulfill his

scholarlymission. This was, as he describedit in August 1912, "to re-explainthe

SanatanaDharma39to the humanintellect in all its parts,from a new standpoint."

Specifically, he would explain "the true meaning of the Vedas,"outline "a new

Science of Philology," and present the true "meaning of all in the Upanishads

that is not understoodeither by Indiansor Europeans."40He worked steadily at

these and relatedprojectsbetween 1910 and 1920, returningto them on and off

until his death in 1950.

Struckby Aurobindo'spassage from Cambridgeclassicist to Sanskritscholar

to revolutionarypublicistto philosophicalyogin, many writershave soughtclues

34. Ibid., 277, 280.

35. Aurobindo,Kena and Other Upanishads,319.

36. Ibid., 346.

37. Ibid., 163.

38. Unnamed English classmate of Aurobindo's, quoted in English in CharuchandraDutta,

PuranokathaUpasanghar(Kolkata:SanskritiBaithak, 1959), 81-82.

39. A Sanskritphrasethat in classical texts means "constantduty"or "invariablelaw."In the nine-

teenth centuryit was reinterpretedas "eternalreligion"and put forwardas an Indianequivalentof the

English term "Hinduism."Aurobindoused it to signify the "religion of Vedanta,"which he believed

to be the supremeexpression of the one universalreligion. I discuss the history of the term sanatana

dharma at some length in " 'The Centreof the Religious Life of the World': SpiritualUniversalism

and CulturalNationalismin the Workof Sri Aurobindo,"in Hinduismin Public and Private: Reform,

Hindutva,Gender and Sampraday,ed. Antony Copley (Delhi: OxfordUniversity Press, 2003).

40. Undatedletter (c. August 1912) to Motilal Roy, publishedin Supplementto the Sri Aurobindo

Birth CentenaryLibrary(Pondicherry:Sri AurobindoAshramTrust, 1973), 433-434.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 179

in his early life, scriptingselected biographicaldata into explanatorynarratives.

His disciples find evidences of the future yogi almost from his birth and the

stamp of divine election on all his actions. The historianLeonardGordoncon-

demns this hagiographicalapproach,offering instead a jejune pop psychology

("Aurobindo'slifelong obsession with motherfigures dates from his childhood,"

"It seems to have been the fear of failure ratherthan God's call or nationalist

speeches that kept him out of the ICS").41More sophisticated and fruitful is

political psychologist Ashis Nandy's "enquiryinto the psychological structures

and cultural forces which supported or resisted the culture of colonialism in

British India,"in which he contrastsAurobindowith RudyardKipling, the latter

"culturallyan Indianchild who grew up to become an ideologue of the moraland

political superiorityof the West," the former "culturallya European child who

grew up to become a votary of the spiritualleadershipof India."Nandy is weak-

est when dealing with Aurobindo's spirituallife, falling back, like Gordon, on

unsubstantiatedguesswork ("Aurobindo'sspiritualismcan be seen as a way of

handlinga situationof culturalaggression,""the 'exotic' alternativehe found to

it [revolution]in mysticism was probablythe only one availableto him"). But his

working assumption is both applicable to Aurobindo and germane to the

Orientalismdebate: "Colonized Indians did not always try to correct or extend

the Orientalists;in theirown diffused way, they tried to createan alternativelan-

guage of discourse."42

Nandy admitsthathis "use of the biographicaldata"of his subjects is "partial,

almost cavalier."43As a result he makes some minor but significant errors in

regardto Aurobindo'slife. For a psychological analysis of a historical figure to

be useful, the datamust be reliable andthe analysis based on a non-reductivethe-

ory thattakes the subject'spersonal and culturalvalues seriously.The following

data seem relevant to a study of Aurobindo'sstyle of orientalism.(1) He spent

his earliestyears in a colonial environmentin India (speakingEnglish, attending

convent school) and his entire youth in England. (2) He developed a distaste for

English life after a brief period of admirationas a child. By his own (retrospec-

tive) account,this was the result of an aestheticreactionto the ugliness andhurry

of life in England,44supportedby a readingof romantic,anti-industrialpoets and

critics: Blake, Shelley, Ruskin, et al. (3) His education was that of a British lit-

erary scholar and civil servant. (4) He admiredthe verbal scholarshipof orien-

talists like MUller,Wilson, and Deussen, but resented their patronizingattitude

towardsIndia and things Indian.(5) While still young he became convinced that

the British occupation of India was unjust, and that he was destined to struggle

against it.45 (6) After his return to India he quickly became re-nationalized

41. LeonardA. Gordon, Bengal: The Nationalist Movement 1876-1940 (New York: Columbia

UniversityPress, 1974), 101, 106.

42. Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism (Delhi:

Oxford University Press, 1988), xvi-xvii, 85-100.

43. Ibid. xvii.

44. Interviewin Empire(Calcutta),9 May 1909.

45. Sri Aurobindo,On Himself (Pondicherry:Sri AurobindoAshramTrust, 1972), 3-4.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

180 PETERHEEHS

throughwhat he later called a "naturalattractionto Indian culture and ways of

life and a temperamentalfeeling and preferenceto all that was Indian."46(7) At

some point he became convinced that the West was in moral and spiritual

decline, and that the inherently superior values of India could help the West

recover its spiritualbalance.

Whatdoes this tell us aboutAurobindoas an orientalist?One thing that seems

certainis that he resentedthe colonial way of writing about the literatures,arts,

religions, and societies of India.Well acquaintedwith the British equivalents,he

was comparativelyimmune to the colonial "myth"of British culturalsuperiori-

ty.47To breakthe debilitatinghold of this myth, which he consideredthe greatest

obstacle to the creation of a revolutionaryconsciousness, he put forward the

oppositemyth of Indiansuperiorityin mattersof the mind and spirit.This was not

in his case simply a strategicmove; it sprangfrom his conviction that in many

importantrespects Indianculture was in fact superiorto Europe's. This feeling

was shared by other Indian nationalists, among them B. G. Tilak and M. K.

Gandhi.

Indiannationalists'assertionsof culturaldifference or claims of culturalsupe-

riority are seen by recent political philosophersas a reversal of the essentialist

premises of colonial orientalism.As SudiptaKavirajputs it: "Orientalism-the

idea thatIndiansociety was irreduciblydifferentfrom the modernWest ... grad-

ually established the intellectualpreconditionsof early nationalismby enabling

Indians to claim a kind of social autonomy within political colonialism."48I

would put it the otherway around:one of the ways the nationalistsassertedtheir

claim of culturaland political autonomywas by deliberatelyreversingthe terms

of orientalistdiscourse. The problem, for the historian,is whether this reversal,

this alternativediscourse, has opened the way to a more accurateaccount of the

Indian past. In studying Indian history, is Indocentrismnecessarily better than

Eurocentrism?

III.FIVEPROBLEMS

ANDAN ASSORTMENT

OFSOLUTIONS

Among the topics Aurobindo touched on in his Indological writings are five

problemsthat are still actively debatedby studentsof Indianhistory: (1) the sig-

46. Ibid., 7. A historianis not obliged to take retrospectiveassertions like this at face value, but

there seems to be less danger in accepting them provisionally, in the spirit of Ricoeur's "second

nalvete"(see Paul Ricoeur, The Symbolismof Evil [Boston: Beacon Press, 1969], 347-357), than in

imposing an alien explanatoryframeworkon them.

47. Pages could be writtensummarizinghow this "myth"was createdand enforcedby Britishlaw,

anthropology,architecture,ceremony, etc., as well as by military force. The most interestingof the

recent Foucault-inspiredstudies of imperial disciplines, such as those in Chatterjeeet al., Textsof

Power: Emerging Disciplines and Colonial Bengal (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

1995), are concerned with various aspects of this myth-creation.To my mind, however, such studies

give far too much importanceto disembodied"discourse"and too little importanceto deliberateper-

sonal, political, diplomatic, and militaryforce.

48. SudiptaKaviraj,"Modernityand Politics in India,"Daedalus 129 (Winter2000), 141. Kaviraj

here draws on, and cites, ParthaChatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments (Princeton:Princeton

University Press, 1993).

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 181

nificance of the Vedas, (2) the date of the vedic texts, (3) the Aryaninvasion the-

ory, (4) the Aryan-Dravidiandivide, and (5) the idea that spirituality is the

essence of India.In this section I sketch the outlines of these problems,and sum-

marize Aurobindo'ssolutions along with those of other orientalistsof the colo-

nial and postcolonial periods. Adopting his nationalisticapproachas my prima-

ry point of reference, I show how his views took shape in a particularhistorical

matrix (of which the biographicalfactors discussed in the previous section are

only one strand)and how they have been criticized and in some cases appropri-

ated by postcolonial writers. Disentangling what is of lasting value in his work

from what belongs to his era, I show that both his critics and admirersmiss out

on his enduringcontributions.If the views of otherorientalistswere subjectedto

a similar triage, it might be possible to approachthe five problems, and others,

with a betterchance of finding satisfactorysolutions.

1. The Significanceof the Vedas

In the Hindu tradition,the hymns of the Vedasoccupy an unusualplace. On the

one hand they are regardedas Divine Revelation, uncreated and the source of

all truth. On the other, they are treated as crude sacrificial formulas, meant to

propitiategods who rewardtheir worshipperswith welfare, progeny, and so on.

Patronizingorientalists, interested only in the ritual interpretation,studied the

Vedas as interesting relics of primitive humanity. Romantic orientalists gave

their attentionnot to the hymns (the karmakandaor "action part"of the Vedas)

but to the Upanishads(thejnanakandaor "knowledgepart"),which deal among

other things with mystical knowledge. Aurobindotoo was at firstinterestedonly

in the Upanishads, accepting passively the ritual interpretationof the hymns.

Later he theorized that the hymns present, in symbolic form, the same knowl-

edge that later was given intellectual expression in the Upanishads.According

to his theory, the hymns are concerned outwardlywith gods and sacrifices but

inwardly with the attainmentof divine knowledge and bliss. Their language is

deliberately equivocal, having at the same time a ritual and spiritual signifi-

cance.49

Incompletely worked out, mystical in intent, Aurobindo's theory has found

few takers among academic orientalists. Dutch Sanskritist Jan Gonda asserts

thatAurobindogoes "decidedly too far in assuming symbolism and allegories."

Indian philosopher S. Radhakrishnanwrites that it would be unwise to accept

his theory, since it "is opposed not only to the modem views of European

scholars but also to the traditionalinterpretationsof Sayana and the system of

Purva-Mimamsa."5o Aurobindo's followers of course endorse his reading, but

only one, T. V. Kapali Sastry,founds his exposition on an independentstudy of

49. Sri Aurobindo,The Secret of the Veda(Pondicherry:Sri AurobindoAshramTrust, 1998).

50. JanGonda, VedicLiterature(Samhitasand Brahmanas).A History of IndianLiterature,vol. I. 1

(Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz,1975), 244; S. Radhakrishnan,Indian Philosophy, vol. 1 (London:George

Allen & Unwin, 1941), 70.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

182 HEEHS

PETER

the Sanskrittexts and commentaries.51The others simply base their assertions

on Aurobindo's authority.52

Most critical scholars of the postcolonial period follow the lead of their

patronizingpredecessorsin regardingthe Vedas as documentsof greathistorical

and linguistic value but no literaryor philosophical interest.At the other end of

the spectrum,reactionaryscholars see the Vedas as repositoriesof extraordinary

wisdom, much of it in advance of modem science.53Few of them have enough

knowledge of Vedic Sanskritto argueintelligentlyin favor of this hypothesis.For

most the Vedas arejust unchallengeableevidence of the antiquityand superiori-

ty of Indianculture.Reductive orientalistsregardthis sort of interestin the Vedas

as an expression of a postcolonial nostalgia for origins, with worrisomeapplica-

tions to the reactionaryproject of imposing essentialist Hinduism on the Indian

state.

Given the millenniathat separateus from the texts, and the paucityof non-tex-

tual supportingmaterials,it is unlikely that we will ever know what the Vedas

meant to their creators.Reactionaryscholars rely on little but faith when they

make theirextraordinaryclaims. It is easy for criticalscholarsto underminethese

assertions,but their own interpretationsleave much to be desired.Like the read-

ings of an arthistorianwho knows everythingaboutthe provenance,iconography,

and formal structureof a quattrocentopainting but nothing about Christianity,

theirwork seems often to be an empty display of linguistic and historicalvirtuos-

ity. Aurobindo'stheory accountsin principlefor the historicalas well as the spir-

itual sides of the texts, but in practicehe gives almost all his attentionto the lat-

ter.54This omission is the primaryweakness of his theory,which to be truemust

permitboth an inwardand an outwardreadingof every hymn.

2. The Date of the Vedas

PrecolonialIndian scholars were for the most partuninterestedin the historical

origin of the Vedas, regardingthem as eternal and uncreated.TraditionalIndian

51. T. V. Kapali Sastry, Collected Worksof T. V. Kapali Sastry. 12 vols. (Pondicherry:Dipti

Publications,1977-1992). Although Sastry attemptsto show the superiorityof Aurobindo'sinterpre-

tationto the "European"interpretationand to the traditionalinterpretationpreservedprimarilyin the

workof the fourteenth-centuryritualisticcommentatorSayana,he admitsthathe has "generallytaken

Sayana as his model in regardto word-for-wordmeaning, grammar,accent, etc." (Collected Works,

vol. 4, ix).

52. See, for example, Kireet Joshi, The Portals of Vedic Knowledge (Auroville, India: Editions

Auroville Press International,2001); Rigveda Samhita, ed. R. L. Kashyap and S. Sadagopan

(Bangalore:Sri AurobindoKapali ShastriInstituteof Vedic Culture,1998).

53. Typical claims are that the rishis ("seers"of the Vedas) knew about airplanes,atomic energy,

and cloning. Such absurditiesmake it difficult for people to accept that Indian mathematiciansand

scientists did make some remarkablediscoveries, such as the Pythagoreantheorem (before Pythag-

oras) and the revolutionof the earth (before Copernicus).It might be added that neitherof these dis-

coveries had generalizedscientific or culturalconsequences in India.

54. See Aurobindo,Secret of the Veda,8, 139. Sastry arguesin Aurobindo'sdefense that the ritu-

al meaning "was unimportantwith the Rishis as that was intendedas an outer cover for guardingthe

secret knowledge" (Collected Works,vol. 1, 17). This is unconvincing. The ritual meaning and its

associatedpracticesare still currentafter more than two millennia, while Aurobindo'sexoteric mean-

ing is not partof the extant indigenous tradition.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 183

chronology,which deals in cycles of millions of years, is not much help in plac-

ing the texts in a historical framework.DocumentaryIndian chronology begins

with the Buddha around 600 BCE.The Vedas predate the Buddha, but by how

much? By estimating the rate of change between the language of datable texts

and the Sanskritof the Rig Veda,eighteenth-and nineteenth-centuryorientalists

such as William Jones and Max Miiller arrived at a date around 1000 BCE.55

Other scholars (most of them Indian)have tried to push the date back by a cou-

ple of thousandyears or more. B. G. Tilak, a scholar and nationalistassociate of

Aurobindo's, proposed a date not later than 4000 BCEand perhaps as early as

6000 BCE.56 Aurobindohimself showed little interestin the question. In his pub-

lished writingshe accepted provisionallya date of threeand half thousandyears

before the present,but suggested the actualdate might be much earlier.

Modem critical orientalists stand by their colonial predecessors, placing the

Rig Vedano earlier than 1900 BCEand generally centurieslater.They offer lin-

guistic and archeological data to support this dating but admit that they lack

knock-down arguments,since the texts of the Vedascontainno sure datingclues,

and accuratelydated artifactscannot surely be correlatedto the texts. The one

thing thatmight decide the matterwould be the deciphermentof the scriptof the

HarappanCivilization ("mature"phases c. 2600 to c. 1900 BCE).First excavated

in the 1920s, and so unknownto earlierorientalists,this long-forgottenciviliza-

tion has become an importantbattlefieldin the contemporaryIndianculturewars.

It is certainthat the Harappanpeople createdone of the most extensive societies

in ancientEurasia.But what was theirrelationto Vedic culture?If the Vedaswere

composed after the decline of Harappanculture, the claim made by romantic,

nationalist,and reactionaryorientaliststhatthe Vedas are the primordialsources

of Indian civilization fails. Passions in this debate run remarkablyhigh, though

few of the participantsknow enough about linguistics, paleontology, archaeolo-

gy, and history to make significantcontributions.57Verybriefly,critical oriental-

ists argue that the differences between the urbanHarappanculture and the pas-

toral culturedescribed in the Vedas are too great for the two to be the same. A

familiar argumentcites the lack of reliable evidence of the horse in Harappan

cities. (The Vedas are filled with references to horses.) Reactionaryorientalists

read the evidence so as to make the Harappancities a late efflorescence of Vedic

culture.N. S. Rajaram,writing on the website of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad,an

aggressive sectarian group, asserts without evidence that "the Vedic and

Harappancivilizations were one."58Rajaramalso is co-author of a book pur-

55. Miiller's linguistic computations,by which he dated the Rig Vedato 1000 BCE,are explained

in Gonda, VedicLiterature,22. William Jones arrivedby a differentmeans at a date of c. 1200 BCE

(Works,volume 7, 79).

56. B. G. Tilak, The Orion or Researches into the Antiquity of the Vedas [1893], in Samagra

LokmanyaTilak,vol. 2 (Poona:Kesari Prakashan,1975).

57. The various issues in these and other fields are comprehensivelyand even-handedly summa-

rized in Edwin Bryant,The Questfor the Originsof VedicCulture:TheIndo-AryanMigrationDebate

(Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002).

58. N. S. Rajaram,"Vedic-Harappan Gallery,"http://www.vhp.org/englishsite/hbharat/vedicharap-

pan_gallery.htm(accessed 6 July 2002).

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

184 PETERHEEHS

portingto show that the language of the Harappanscript is Sanskrit.This deci-

pherment,which has won no acceptance,has been shown to be based in parton

doctoredevidence.59Argumentsand counter-argumentson this andrelatedques-

tions fill books, academic papers, Sunday supplement features, and internet

newsgroups.The rhetoricreveals the preconceptionsand attitudesof the partici-

pants. Critical scholars, versed in the primaryand secondary literature,lay out

impressive data with a show of objectivity but often betray a superciliousness

similar to that of colonial orientalists.Their reactionaryopponentsmake up for

lack of linguistic knowledge by attackson their opponents,Max Mtiller,and the

British Empire, and half-informed invocations of nationalist orientalists like

Tilak and Aurobindo.60

3. TheAryanInvasion Theory

Aurobindo never referredto the HarappanCivilization, which was excavated

afterhe wrote his majorworks. He did sometimes speak of an issue relatedto the

Harappanpuzzle: the question of the Aryans' homeland. Colonial orientalists

theorizedthat Sanskrit,Greek,Latin, and so on were all descendedfrom an ear-

lier language spoken by a distinct group of people in a fairly compacthomeland,

who dispersed in various directions. These people were formerly known as

"Aryans."61Much scholarlyingenuity has been expended in the search for their

homeland,sites as disparateas India and Scandinaviabeing proposed.A consen-

sus eventuallyemerged thatthe homelandwas located in centralor westernAsia.

The southeasternAryantribeswere thoughtto have enteredIndia as conquerors,

displacing the earlier Dravidianinhabitants,who spoke languages unrelatedto

Indo-European.Not long after the formulationof this "Aryan-invasion"theory,

it was recognized that conqueringor even migrating"races"are not requiredfor

the dispersionof languages;but the damage had alreadybeen done. Takenup by

romantic orientalists in nineteenth-centuryGermany, the hypothetical "Aryan

race"began a career that even the defeat of Nazism could not end.

Aurobindowas unconvincedby the Aryan invasion theory,pointing out that

Indian tradition,including the texts of the Vedas, makes "no actual mention of

any such invasion."62In one or two drafts not published duringhis lifetime, he

said that the theory was a "philologicalmyth"foisted on the world by European

scholars.He suggested thatthis and other speculationsbe brushedaside in order

to "makea tabularasa of all previoustheoriesEuropeanor Indian[bearingon the

meaning of the Vedas] & come back to the actualtext of the Veda for enlighten-

59. N. Jha and N. S. Rajaram,TheDeciphered Indus Script(New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan,2000).

Michael Witzel and Steve Farmer,"Horseplayin Harappa,"Frontline 17 (30 September-13 October

2000), 1-14.

60. See Jha and Rajaram,The Deciphered Indus Script, and Michel Danino, Sri Aurobindoand

Indian Civilisation (Auroville: EditionsAuroville Press International,1999).

61. The modem word "Aryan"comes from the vedic arya, which was takento be the name of the

"race"that composed the Vedas.In modern scholarly literature,the presumedlinguistic ancestor of

Sanskrit,Greek, Latin, etc. is known as Proto-Indo-European;the presumedpeople who spoke this

language are often called Indo-Europeans.

62. Aurobindo,Secret, 26.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 185

ment."63But when he came to publish his findings, he simply expressed doubt

aboutthe Aryan invasion theory withoutdenying the possibility thatan "Aryan"-

speaking people may have enteredthe subcontinentfrom the north.64He some-

times spoke favorably of Tilak's hypothesis that the Aryans dwelt originally in

the arctic region and later migratedto India.65For the most part, however, he

showed little interest in the historicalorigins of vedic culture.This has not pre-

vented reactionaryorientalists from enrolling him posthumously in their cam-

paign to destroy the Aryan-invasiontheory, which they view as a creation of

colonial orientalismmeant to transferthe sources of Indian culture to a region

outside India. Such writers often cite Aurobindo'smanuscriptdrafts but ignore

the more cautious references in his published writings.66

Those who campaign against the Aryan-invasiontheory are flogging a long-

dead horse. Critical scholars abandonedit decades ago in favor of a theory that

holds that speakers of Indo-Aryan (the presumed predecessor of Sanskrit)

entered the subcontinentin one or more migrations.67The relationbetween the

differentbranchesof the Indo-Europeanfamily is linguistic; race does not enter

into it. (This is a point Aurobindoinsisted on as early as 1912.) Criticalscholars

do maintain, however, that the linguistic distinction between Indo-Aryanand

Dravidianlanguages is valid.

4. TheAryan-DravidianDivide

In the late nineteenthcentury,the distinctionbetween the Indo-Aryanlanguages

of northernIndia and the Dravidianlanguages of the South was seized upon by

colonial ethnologists, who made it a benchmarkin their survey of Indianphysi-

cal types. The "Dravidianraces,"inhabitingsouth and centralIndia,were depict-

ed as dark,flatnosed, etc., in contradistinctionto the "Indo-Aryans"of the North,

who were almost like Europeans.68Linguistic databecame the basis of an ethno-

graphicsplit between two essential types, who were said to be at odds with each

other.69The Aryan invasion was used to plot this work of historical fiction. The

63. Sri Aurobindo, "The Gods of the Veda [second version]." Sri Aurobindo: Archives and

Research8 (1984), 136; cf. Aurobindo,"ASystem of Vedic Psychology: Preparatory," in Supplement,

183.

64. Aurobindo,Secret, 26, 31, 38.

65. Aurobindo, Secret, 31. See B. G. Tilak, The Arctic Home in the Vedas [1903], in Samagra

LokmanyaTilak,vol. 2.

66. FrangoisGautier,RewritingIndian History (New Delhi: Vikas PublishingHouse, 1996), 7-8;

David Frawley,TheMythof the AryanInvasion oflndia (New Delhi: Voice of India, 1998), 8; Michel

Danino and SujataNahar,The Invasion ThatNever Was(Delhi: The Mother's Instituteof Research,

1996), 39-43; Michel Danino, The Indian Mind Then and Now (Auroville: Editions Auroville Press

International,1999), 44; Danino, Sri Aurobindoand Indian Civilisation,53.

67. See for example Romila Thapar,The Past and Prejudice (Delhi: Oxford University Press,

1975), 26; Thapar,"The Theory of Aryan Race and India: History and Politics." Social Scientist 24

(January-March1996), 3-29. The migratorytheory appearsin all up-to-datetextbooks, e.g. Hermann

Kulke and DietmarRothermund,History of India (New York:Routledge, 1998), 30.

68. HerbertRisley, The People of India (Calcutta:Thacker,Spink & Co., 1908).

69. In this connection,see Risley's ridiculous(but at the time dangerous)misreadingof a Buddhist

bas-relief,which he presentsas "the sculpturedexpressionof the race sentimentof the Aryanstowards

the Dravidians"(ibid., 5).

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

186 PETER

HEEHS

almost-EuropeanAryanspushed the dark,flat-nosedDravidiansfrom the fertile

plains of the North into southernIndia. Isolated texts were cited to supportthis

theory.The word anasa, which occurs once in the Rig Vedain a descriptionof

the Aryan's enemies, was taken to mean "noseless," that is, flat nosed. This

accordedwell with the "racialscience"of the era. In 1872 a Frenchwriterof pop-

ular scholarshipnoted that the seers of the Vedas often spoke of their "negro"

enemies as "thenoseless ones," thus "revealingan anthropologicalcharacteristic

of greatimportance."70

WhenAurobindoarrivedin South India in 1910, he was surprisedto discover

no radical physical difference between his new neighbors and people in the

North.Eventuallyhe became convinced that"the [racial]theory which European

erudition started"was wrong, and that "the so-called Aryans and Dravidians"

were parts of "one homogenous race."71When he began to study Tamil he was

furthersurprisedto find "thatthe originalconnection between the Dravidianand

Aryantongues was far closer and more extensive thanis usually supposed."This

led him to speculate that "thatthey may even have been two divergentfamilies

derived from one lost primitive tongue."72He never went so far as to assertthat

Tamilwas an "Aryandialect,"but he did question the methodology and conclu-

sions of Europeanphilology, which used meager data to arrive at grandconclu-

sions. In this connection, he ridiculed the reading of anasa as "noseless."This

was, he said, not just bad etymology but also bad ethnology, "for the southern

nose can give as good an account of itself as any 'Aryan' proboscis in the

North."73

Aurobindo'sphilological research,preservedin hundredsof pages of notes on

Sanskrit, Latin, Greek, Tamil, and other languages, helped convince him that

Europeancomparativephilology was overrated.He liked to allude to a remark

by ErnestRenan characterizingphilology as a "pettyconjecturalscience."74His

citation(apparentlyfrom memory) was somewhat inaccurate,75 thoughhis belief

that the philology of the period promisedmore than it delivered is one that few

today would question.

70. G. Lietard,Les peuples ariens et les langues ariennes (Paris:G. Masson, 1872), 13.

71. Aurobindo, Secret, 25, 593. Aurobindo did, however, acknowledge a difference in culture

between the "Aryans"of the northand center and the inhabitantsof the south, west, and east (see Sri

Aurobindo,The Hour of God and Other Writings[Pondicherry:Sri AurobindoAshramTrust, 1972],

278).

72. Aurobindo,Secret, 38.

73. Ibid., 26.

74. Ibid., 50; cf. ibid. 29; Hour of God, 298; Supplement,180; "The Secret of the Veda"(manu-

scriptdraft),Sri Aurobindo:Archivesand Research9 (1985), 42.

75. What Renan wrote, in an ironic passage of his memoirs, was that if he hadn't gone to Saint-

Sulplice and learned Hebrew,German,and theology, he might have become a naturalscientist.As it

was his studies led him to the "historicalsciences, little conjecturalsciences, that forever are unmak-

ing themselves as soon as they are made and are forgotten in a hundredyears" (Souvenirsd'enfance

et de jeunesse [Paris:Nelson Editeurs, n.d.], 190). There is no special mention of philology. (Renan

did importantwork in many "historicalsciences," philology among them.) The French savant was

simply giving expression to the usual longing of the social scientist for the neatness and precision of

the naturalsciences.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 187

Moderncritical orientalistswould agree with Aurobindothat the ethnological

theories of colonial scholarsarepolitically suspect and scientificallyworthless.76

They would reject his idea that the Dravidianlanguages may have sprungfrom

the same protolanguageas Sanskrit.77Reactionaryorientalists distorthis views

on this matter,turninghis cautious speculationsinto positive assertionsand sup-

porting their rejection of historical linguistics by means of his misquotationof

Renan.78

5. Spiritualityas the Essence of India

When the culture of India was introducedto Europe, it was made to look pre-

dominantlyreligious. Travelersand missionarieswrote aboutthe country'sexot-

ic faiths. Translationsof texts like the Bhagavad Gita lent supportto the notion

that Indians were uniquely preoccupied with spirituality.The stereotypeof the

"mystical Indian" was not without its use in a colonial state: otherworldly

Indians needed down-to-earth Englishmen to rule over them. The mystical

stereotype was confirmed and extended by Romantic orientalists, scholarly as

well as flaky.In 1882 the TheosophicalSociety moved to India, which soon dis-

placed Egypt as "the source of the ancient wisdom."79New forms of traditional

religions took shape. Vivekananda,founderof the RamakrishnaMission, spoke

of an Indiathat was chiefly distinguishedfrom Europeby its inherentspirituali-

ty. "That nation, among all the children of men, has believed, and believed

intensely,that this life is not real. The real is God; and they must cling unto that

God throughthick and thin. In the midst of their degeneration,religion came

first."80

Aurobindoagreed with Vivekanandathat spiritualitywas the essence of India,

but he insisted that it was not the whole of what he called "the Indianmind."He

begins a key paragraph:"Spiritualityis indeed the master-key of the Indian

mind,"but goes on to say thatIndia "was alive to the greatnessof materiallaws

and forces; she had a keen eye for the importanceof the physical sciences; she

knew how to organisethe artsof ordinarylife. But she saw thatthe physical does

not get its full sense until it stands in right relationto the supra-physical."81He

was awareof the influence of colonial discourse on the formationof this image,

and tried to enlarge it beyond Westernstereotypes:

76. See Trautmann,Aryans and BritishIndia.

77. See Ibid., 131-164. One well-published linguist writes that "it is quite clear that Chukchi-

Kamchatkanand Eskimo-Aleut ... are both closer to Indo-EuropeanthanAfro-Asiatic or Dravidian

is" (MerrittRuhlen,The Origin of Language: Tracingthe Evolutionof the MotherTongue[New York:

John Wiley, 1994], 134-135).

78. Danino and Nahar,Invasion, 42; India's Rebirth,ed. SujataNahar et al. (Mysore, India:Mira

Aditi, 1996), 96; Rajaramand Jha, The Deciphered Indus Script, 18; Rajaramand Frawley, Vedic

Aryans, xvi, 118.

79. Mark Bevir, "The West TurnsEastward:Madame Blavatsky and the Transformationof the

Occult Tradition,"Journal of the AmericanAcademyof Religion 62 (1994), 756.

80. Swami Vivekananda,"My Life and Mission," in The Collected Worksof Swami Vivekananda

(Calcutta:AdvaitaAshrama, 1989), vol. 8, 74.

81. Sri Aurobindo,The Renaissance in India with A Defence of Indian Culture(Pondicherry:Sri

AurobindoAshramTrust, 1997), 6.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188 PETER

HEEHS

Europeanwriters,struckby the generalmetaphysical bent of the Indianmind,by its

strongreligiousinstinctsandreligiousidealism,by its other-worldliness,areinclinedto

writeas if thiswereall the Indianspirit.An abstract,metaphysical,

religiousmindover-

poweredby the senseof the infinite,not aptfor life, dreamy,unpractical,turningaway

fromlife andactionas Maya,this,theysaid,is India;andfor a timeIndiansin thisas in

othermatterssubmissivelyechoedtheirnewWesternteachersandmasters.82

In fact, Aurobindoclaimed, the Indianspiritcomprised"an ingrainedand domi-

nant spirituality,""an inexhaustiblevital creativeness,"and "a powerful, pene-

tratingand scrupulousintelligence."83In passages like this he seems practically

to slip into the self-laudatorytone of works like Sarda'sHindu Superiority.Yet

for all his "defence of Indianculture"(the title of his main work on the subject),

he was not blind to the country's limitations. He specifically condemned the

"vulgarand unthinkingculturalChauvinismwhich holds that whateverwe have

is good for us because it is Indian or even that whatever is in India is best,

because it is the creationof the Rishis."84He promotedIndia as aggressively as

he did because of the historicalcircumstancesin which he wrote. It would have

been self-defeatingfor this sworn anticolonialistto be completely evenhandedin

his discussion of Indian culture while European writers were condemning it

wholesale.85

In the postcolonial period, critical historians have tried to revise colonial

depictionsof Indianspiritualculture.The resultshave often been iconoclastic, in

part because many of the better writers are Marxist or Left-leaning. The reac-

tionary orientalists'reaction is against this perceived attack on Indian spiritual

values.86Reductive orientalists,too, have been hardon the romanticand nation-

alist views of Indian spirituality.Some of them depict Aurobindo and other

nationalistwriters as precursorsof today's reactionaryscholarshipas well as of

Hindu identity politics (Hindutva). Peter van der Veer, for example, says that

Aurobindowrote that "theRamayanaand Mahabharataconstitutethe essence of

Indianliterature.This orientalistnotion was foundationalfor the Hindunational-

isation of Indian civilisation."87There is no such statement in Aurobindo's

works, nor it true that his matureviews on Indianspiritualitylend supportto the

monolithic Hindu, anti-Muslimnationalismthat van der Veerjustly criticizes.88

82. Ibid., 5-6.

83. Ibid., 10.

84. Ibid., 75.

85. A Defence of Indian Culturewas written in reply to William Archer's India and the Future

(London:Hutchinson& Co., 1917), a condescending and primarilydestructivecritiqueof Indianlife,

literature,and art.

86. See for example, Arun Shourie, Eminent Historians: Their Technology,Their Line, Their

Fraud (Delhi: Asa, 1998); Rajaramand Frawley, VedicAryans;Nahar et al., eds., India's Rebirth.

87. Peter van der Veer, "MonumentalTexts: The CriticalEdition of India'sNational Heritage,"in

Invokingthe Past: The Uses of History in SouthAsia, ed. Daud Ali (Delhi: Oxford University Press,

1999), 154.

88. Van der Veer cites, without page reference, Aurobindo'sFoundations of Indian Culture,the

editorialtitle under which The Defence of Indian Cultureand other essays were formerlypublished.

There is no passage in these essays in which Aurobindowrites that the two Sanskritepics were the

essence of Indiancivilization. He does say that "theMahabharataand Ramayana,whetherin the orig-

inal Sanskritor rewrittenin the regional tongues, broughtto the masses by Kathakas-rhapsodists,

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.113 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 19:46:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SHADES OF ORIENTALISM 189

Otherreductive writersgo fartherthan van der Veer in reducing Indian spiri-

tuality to a construct of colonial-period orientalism. Ronald Inden writes that

Europeancolonial scholars "constitutedHinduism and broughtit into relation-

ship to the religion and science of Europe."Richard King seconds this: "The

notion of a Hindu religion ... was initially invented by WesternOrientalistsbas-

ing their observationson a Judeo-Christianunderstandingof religion."89If the

intentof such assertionsis thatthe Europeanview of "Hinduism"as a single reli-

gion like Judaism or Christianityis a European invention, there could be no

objection,since the statementis tautologicallytrue.If it is suggestedthatthis and

other Europeannotions have had a massive impact on Indians'ways of viewing

themselves and their beliefs and practices,any objection would be futile, since

the intellectualhistory of India since the seventeenthcentury gives ample testi-

mony to such influence. But if the meaning is that EuropeanscreatedHinduism

ex nihilo and that precolonial Indians had no ideas about themselves and their

religious practices and beliefs, one would have to be a very orthodox Foucauld-

ian to accept it.

A serious investigationinto the formationof culturalideas in India would have

to begin with the precolonialperiod,thatis, the threethousandyears thatprecede

the colonial era. Hundreds of traditions are preserved, to a greater or lesser

degree, in texts writtenin a dozen or more languages.90Even a cursory study of

the textual, historical, and anthropological data makes it clear that religion

reciters, and exegetes-became and remainedone of the chief instrumentsof popular educationand

culture,moulded the thought,character,aesthetic and religious mind of the people and gave even to

the illiterate some sufficient tinctureof philosophy, ethics, social and political ideas, aestheticemo-

tion, poetry, fiction and romance"(Renaissance, 346). The allusion to the translationsand dramatic

presentationsof the epics is interesting,for it is part of van der Veer's argumentthat the neglect of

these populartraditionswas one of the errorsof "orientalist"scholarship.The passage in Aurobindo's

works that comes closest to van der Veer's paraphraseis this one from a very early essay: "Valmiki,

Vyasa and Kalidasa [the authors,respectively, of the Mahabharata,the Ramayana,and several clas-

sical poems and plays] are the essence of the historyof ancient India;if all else were lost, they would

still be its sole and sufficientculturalhistory"(Early Cultural Writings,152). Aurobindo'spoint here

is thatthe threepoets representwhat he then regardedas the three main "moods"of the "Aryancivil-

isation,"the moral, the intellectual,and the material.Hinduismis not mentioned.As for IndianIslam,

see the last chapterof the Defence for Aurobindo'sinclusive attitude.

89. Inden, ImaginingIndia, 89; King, Orientalismand Religion: Postcolonial Theory,India and