Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Psychosocial Approaches To The Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

Uploaded by

Nera MayaditaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Psychosocial Approaches To The Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

Uploaded by

Nera MayaditaCopyright:

Available Formats

CLINICAL SYNTHESIS

Psychosocial Approaches to the Treatment

of Bipolar Disorder

David J. Miklowitz, Ph.D., and Michael J. Gitlin, M.D.

Even when treated with best-practice pharmacotherapy, many patients with bipolar disorder have slow recoveries from

illness episodes, high rates of recurrence, and considerable functional impairment. This article reviews randomized trials of

psychotherapy as adjunctive to pharmacotherapy. There is evidence for the efficacy of family-focused interventions, group

psychoeducation, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy in delaying or preventing

relapses and stabilizing illness episodes. Although these treatments share many common strategies (e.g., psychoeducation),

little is known about how they work, when in the illness progression they should be administered for maximal effect, and how

to efficiently train large numbers of community clinicians. Online versions of psychoeducational care are being developed,

with promising early results. Studies that identify changes in neural circuitry that mediate the effects of psychosocial in-

tervention may be especially informative in clarifying targets of evidence-based psychosocial care.

Focus 2015; 13:37–46; doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.130106

CLINICAL CONTEXT that persist after acute episodes of mania or depression. Sub-

threshold symptoms have considerable prognostic significance:

Bipolar Disorder: Prevalence, Course, and Disability

even mild levels of residual depression are associated with

Bipolar disorder is a highly disabling illness, with average

low levels of psychosocial functioning and high risk for

onset at 18 years, low academic and social achievement in

recurrences (9, 10). Lack of full remission—indicating that the

childhood, high rates of drug or alcohol abuse in adolescence

illness is still active—is associated with a shorter time to

and adulthood, and high rates of suicide and cognitive dys-

recurrences of depression or mania (11). Moreover, many

function throughout the lifespan. The lifetime prevalence in

patients have residual psychosocial impairments following

the United States is 1.0% for bipolar I disorder, 1.1% for bi-

episodes that are not targeted by medications (9, 10). For

polar II disorder, and 2.4% for subthreshold bipolar disorder

example, lack of social support following acute mood epi-

(1), with lower rates in a cross-national epidemiologic study

sodes was associated with more severe depressive symp-

(2). Approximately 2% of adolescents have had manic episodes

toms at 1-year follow-up, especially among patients who did

(3). Across clinical studies conducted in different countries,

not fully recover from the their acute episodes (12). Corre-

lifetime rates of bipolar disorder in childhood converge on

spondingly, treatments that bring the patient to a full and

1.8% (4), suggesting that rates may be increasing in more re-

durable remission and enhance social support during the

cent birth cohorts.

postepisode period are most likely to prevent or delay

Pharmacological regimens for bipolar disorder include

recurrences.

mood stabilizers (commonly, lithium, valproate, or lamotrigine)

or second-generation antipsychotics (i.e., quetiapine, olanza-

pine, aripiprazole, risperidone, ziprasidone, and lurasidone). Psychosocial Treatments as Adjunctive

Antidepressants, when given at all, are usually prescribed to Pharmacotherapy

adjunctively to mood stabilizers. Even with optimal medica- When evaluated against the backdrop of the growing num-

tion regimens, however, only 21%–27% of patients with bi- ber of pharmacological options for bipolar disorder, prog-

polar depression recover fully from episodes within 1 year (5) ress in psychological interventions has been relatively slow.

and 37%–49% have recurrences (6, 7). Five-year relapse rates Yet, adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy has been

in naturalistically treated samples typically range from 60% to found to reduce rates of recurrence by 50% or more com-

85% (8). pared with usual care (13). Additionally, 31 of 35 controlled

Even when treated with best-practice pharmacotherapy, studies examining the efficacy of psychosocial interventions

many bipolar patients have subthreshold depressive symptoms have shown efficacy when compared with control conditions

Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015 focus.psychiatryonline.org 37

PSYCHOSOCIAL APPROACHES TO THE TREATMENT OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

(typically, nonspecific treatments or usual care) (14). Most TREATMENT STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder recommend add-

Common Elements of Psychotherapy

ing psychotherapy (at minimum, psychoeducation sessions

Psychosocial treatments are intended as adjuncts to phar-

focused on illness management) to medications to speed

macotherapy and are typically offered during the post-

recovery from mood episodes, delay or minimize recur-

episode “continuation” phase or the maintenance phase of

rences, and enhance psychosocial functioning (e.g., refer-

treatment. They are present-focused and emphasize learn-

ence 15, 16.).

ing skills for managing the disorder (psychoeducation). Al-

Therapy modalities with evidence of efficacy in bipolar

though the modalities have common objectives (Table 1),

disorder include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), group

there are distinct elements as well: format (e.g., whether

psychoeducation, family-focused therapy (FFT), and in-

treatment is given individually, in groups, or in family units),

terpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT). This article

length (minimum 3–6 sessions and up to 30 or more), and

reviews recent randomized trials of psychosocial inter-

whether treatment is intended for patients in remission,

ventions, emphasizing major strategies, putative therapeutic

those recovering from an acute episode, or both.

ingredients, and limitations. We conclude with clinical and

In the following sections, we review randomized trials of

research recommendations, with particular emphasis on

psychotherapy. Further details of these trials, and coverage

community implementation studies.

of psychotherapy methods that have only been tested in

uncontrolled trials, are available elsewhere (26, 27).

The Role of Stress in Bipolar Disorder

What psychological characteristics of individuals with bi-

polar disorder—or their life contexts—would one seek to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

modify in psychotherapy? When evaluated in remission, CBT approaches to bipolar disorder consist of three core

bipolar patients do not appear to have consistent personality strategies: behavioral activation (i.e., helping patients to in-

types or patterns of dysfunctional thinking that distinguish crease activity levels when depressed and “dial it down” when

them from individuals with other disorders. There is evi- their moods escalate), relapse prevention (identifying pro-

dence, however, that many bipolar patients are highly stress- dromal symptoms of new episodes and implementing pre-

sensitive (i.e., prone to rapid recurrences following life emptive plans), and cognitive restructuring (modifying

stressors; 17, 18) and that childhood adversity (i.e., sexual, automatic negative thoughts and core dysfunctional beliefs).

physical, or emotional abuse) potentiates this stress sensi- Behavioral activation may include reducing daily activities to

tivity (19, 20). Life events that cause changes in sleep/wake avoid overstimulation, even if these events are pleasurable.

rhythms (21) or increases in goal-directedness (22) may Cognitive restructuring may involve challenging “hyperposi-

precipitate manic symptoms in otherwise stable patients. tive” thinking (e.g., “I cannot lose…I’m in complete control of

Negative life events, such as the loss of a significant other, are my fate”) as well as overly pessimistic thinking.

more closely associated with depressive episodes, especially Cognitive-behavior therapy has the most extensive re-

in the absence of adequate social supports (18). cord of randomized trials in bipolar disorder, although CBT

Much like patients with other psychiatric disorders, bi- protocols vary from study to study. In the U.K. study of Lam

polar patients are quite sensitive to family conflict and dis- et al. (28), 103 euthymic patients with bipolar disorder were

tress. Bipolar patients who have caregivers who are high randomly allocated to CBT (12–18 sessions) plus pharma-

in “expressed emotion” when discussing the patient with cotherapy or usual care (pharmacotherapy alone). CBT

a clinician (i.e., express highly critical, hostile, or overpro- emphasized psychoeducation, challenging dysfunctional

tective attitudes or beliefs) or when interacting directly cognitions, and medication adherence monitoring. At 1 year,

with the patient are more likely to relapse over 9 months 44% of the patients in CBT had relapsed versus 75% of those

than those in less affectively charged (low expressed emo- in usual care. At 30 months, patients in CBT no longer dif-

tion) caregiver/patient relationships (23). Most recently, the fered from patients in usual care on time to overall relapse,

role of childhood adversity has been highlighted as a pre- but they did have fewer depressive relapses and days in mood

dictor of initial and recurrent mood episodes (20). In the episodes.

Stanley Foundation multisite study of bipolar disorder, sex- Scott and associates (29) examined 22 sessions of CBT

ual and physical abuse were associated with earlier age at compared with treatment as usual (TAU) among 253 bipo-

onset, more medically serious suicide attempts, more illness lar patients treated in five U.K. mental health centers. Un-

episodes, and substance abuse comorbidity (24, 25). like the Lam et al. (28) study, patients began in a variety of

Thus, stress plays an important role in the onset of mania symptom states. No differences were found between CBT

and depression among individuals with bipolar disorder, and TAU on time to recurrence over 18 months. However,

through both genetic and environmental risk pathways. a post hoc analysis revealed that patients who had fewer

Conversely, teaching patients strategies for coping with prior episodes were more likely to have recurrences in TAU

stressful events, even if they do not directly address child- (55%) than in CBT (41%), whereas recurrences were more

hood contexts, may reduce the impact of such stressors on likely among those who had many prior episodes in CBT (81%)

relapse and psychosocial impairment. than TAU (66%). These results suggest two possibilities: CBT

38 focus.psychiatryonline.org Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015

MIKLOWITZ AND GITLIN

is best suited to the earliest phases of the disorder, or CBT TABLE 1. Objectives of Adjunctive Psychotherapy for Bipolar

may be unsettling and agitating to patients who are unstable, Disorder

have a more refractory illness, or have more cognitive Improve ability to identify and intervene early with incipient signs

impairment. of relapse

In a well-designed Canadian trial of 204 patients in full or Enhance emotion-regulation skills

partial remission, participants were randomly assigned to 20 Improve family relationships (i.e., enhance interpersonal

sessions of individual CBT or 6 sessions of group psycho- communication and problem-solving)

education (30). No differences emerged over 1.5 years in Increase acceptance of the disorder and its treatments

symptom severity or recurrence rates. Given that group psy-

Enhance adherence with medication regimens

choeducation cost an average of $180 per participant whereas

CBT cost $1,200 per participant, group psychoeducation Stabilize sleep/wake cycles and other daily or nightly routines

would appear to be the more cost-effective alternative. Reduce drug and alcohol abuse

Finally, investigators at the University of Tubingen, Ger-

many randomized 76 patients to 20 sessions of CBT or 20

sessions of individual supportive therapy, both with phar- in manic episodes than patients who received usual care.

macotherapy (31). The patients had subthreshold manic or Patients in multicomponent care also had significant im-

depressive symptoms, but none were in an acute episode. No provements in social functioning and quality of life.

differences were observed in relapse rates over 33 months The largest randomized trial in bipolar disorder (N=441)

(overall rate, 64.5%). The authors point to the common ele- tested a similar 2-year multicomponent care intervention—

ments of the two approaches (i.e., provision of information, with group psychoeducation at the same frequency—within

systematic mood monitoring) in explaining the lack of dif- the Kaiser Permanente health network (36). Patients in the

ferences on relapse. Additionally, the length of the two treat- multicomponent intervention had lower mania scores and

ments proved informative: risk for relapse decreased by 10% spent less time in manic or hypomanic episodes than pa-

with each therapy session that patients attended, regardless of tients in a usual care condition. Neither this study nor the

the treatment condition. Bauer et al. study found effects of the multicare program

on depressive symptoms. “Dismantling” design studies, in

Group Psychoeducation which modules of multicomponent treatments are tested

Several research teams have evaluated group treatment in with and without each other, will provide one avenue for

conjunction with pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention. determining the unique contribution of group psycho-

Group treatments take advantage of the social support pro- education to symptom outcomes.

vided by other patients, who may enliven psychoeducation An adaptation of structured psychoeducation groups

with real-life examples. Colom and associates (32) at the called “functional remediation treatment” emphasizes

University of Barcelona tested a 21-session group treatment patients’ cognitive functioning, with exercises designed to

that included exercises to promote greater awareness of improve memory, attention, problem solving, and organiza-

illness states, early detection and intervention with pro- tional skills. In a 10-site randomized trial in Spain, 268 patients

dromal symptoms, the importance of medication adherence, were assigned to 21 weekly group sessions of functional re-

and enhancing stability through lifestyle (e.g., sleep/wake mediation, 21 sessions of standard group psychoeducation,

cycle) regularity. Although this group treatment had ele- or TAU (37). Patients in the functional remediation groups

ments in common with CBT, it made minimal use of cog- showed greater improvements in psychosocial functioning

nitive restructuring or behavioral activation (pleasant than those in TAU, but fared only slightly better than patients

events) schedules (33). Colom et al. found that, over 2 years in the standard psychoeducation groups.

a 21-session structured psychoeducation group was associated Hence, group psychoeducation has been shown to be

with fewer recurrences (67% versus 90%) and better psy- an effective and, in all probability, cost-effective adjunct

chosocial functioning than a 21-session support group (32). to pharmacotherapy for patients with bipolar disorder. Its

Over 5 years, patients who had received the structured role in treating and preventing manic symptoms is more con-

groups had far fewer days of acute illness (mean 154 days) sistent than for depressive symptoms. Research on the pro-

compared with those who received the unstructured group cesses that mediate the effects of group psychoeducation—for

(586 days) (34). example, whether being treated alongside of others leads

Two randomized trials examined the effectiveness of to decreased stigmatization and a greater willingness to

group psychoeducation within the context of multicom- adopt illness management strategies—may lead to the de-

ponent care plans. In 11 Department of Veterans Affairs velopment of even more powerful group approaches. Group

sites (35), 306 patients received mood monitoring from treatments may be more difficult to implement in public or

a nurse care coordinator and group psychoeducation (5 private settings where treatment is dispersed across dif-

weekly followed by twice monthly groups for up to 3 years) ferent providers and locations, but the availability of Skype

to improve relapse prevention skills. Over a 3-year period, and other online communication tools may minimize these

patients in the multicomponent program spent fewer weeks limitations.

Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015 focus.psychiatryonline.org 39

PSYCHOSOCIAL APPROACHES TO THE TREATMENT OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

Family-Focused Treatment (FFT) (30%) children (ages 8–12 years) were randomly assigned to

Given in up to 21 weekly followed by biweekly sessions immediate 6-month group treatment or a delayed group

during the postacute (continuation) period, FFT aims to treatment in which treatments were given from study

hasten stabilization and reduce the likelihood of recurrences months 12–18. Over 1 year, children whose families partici-

of bipolar disorder (38). In the initial treatment phases, pated in the immediate groups showed greater improvement

patients and family caregivers (usually spouse or parents) in affective symptoms than children whose families were

are instructed in how to recognize early warning signs of waitlisted (49). The clinical benefits of psychoeducation

mania or depression and develop prevention strategies (e.g., were mediated by improvements in parents’ ability to ad-

how best to alert the patient to changes in his or her moods vocate for their child’s mental health care and the higher

or behavior, rehearsing what to say to the attending psy- quality of services utilized. In turn, quality of services was

chiatrist). Assisting patients in stabilizing their sleep/wake associated with improved mood symptoms in children over

cycles and staying adherent to medications are also key 1 year (50).

strategies of family psychoeducation; however, clinicians The 12-session child and family-focused cognitive be-

encourage family members to recognize their roles in these havioral therapy program (also known by the acronym

problems (e.g., a parent who sets no limits on a 15-year old “RAINBOW”) incorporates single-family psychoeducation

who stays up all night playing video games, a spouse who sessions with individual parent psychoeducation and CBT

supports the patient in believing that marijuana is a good for the child (cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation

substitute for mood stabilizers). In later stages of FFT (6–9 [pleasurable events scheduling], and mindfulness meditation)

months), clinicians assist families in skills training for en- (51). In a randomized trial with 69 children and adolescents

hancing communication (i.e., learning to listen actively, re- (ages 7–13, mean 9 years) who also received medication

quest changes in each other’s behavior, offer both positive management, greater improvements were observed over 6

and constructive negative feedback) and problem-solving. At months for mania symptoms, depressive symptoms, and

this point, patients are often able to return to tasks that were global functioning scores compared with an equally in-

on hold during and following acute episodes (e.g., parenting tensive psychosocial TAU condition (51).

of young children). FFT has been examined in two trials with bipolar ado-

Unlike CBT or group psychoeducation, FFT sessions always lescents (FFT Adolescent version, or FFT-A). In the first,

involve family members, and skills training focuses on im- adolescents with bipolar I, II, or not otherwise specified

proving family relationships. Cognitive restructuring is not disorder who received 21 sessions of FFT and pharmaco-

a key component of treatment except in cases where, for ex- therapy had more rapid recovery from depressive episodes

ample, patients’ or caregivers’ attitudes are based on mis- at study entry, less time in depressive episodes at follow-up,

information about the illness (e.g., “lithium destroys brain and more time well over 2 years compared with adolescents

cells”; “bipolar disorder is no different than just being moody”). in brief psychoeducation (“enhanced care”) and pharmaco-

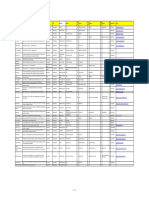

Table 2 summarizes the randomized trials of FFT in therapy (40). A second trial involving 145 adolescents with

adults and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Overall, FFT bipolar I or II disorder treated over three sites did not replicate

and pharmacotherapy have been associated with a 35%–40% these results: adolescents in FFT-A and those in enhanced care

reduction over 2 years in recurrence rates compared with (both administered with best practice pharmacotherapy) were

brief psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy, with numbers equivalent in time to recovery and time to recurrence. Ado-

needed to treat (NNTs) ranging from 5 to 10 (39–48). In several lescents in FFT-A, however, had fewer severe manic symptoms

trials, effect sizes for FFT (compared with brief treatment) have in the second study year than those in enhanced care (39).

been stronger in patients from families with high expressed Children and teens who are at high risk for bipolar dis-

emotion than from families with low expressed emotion, sug- order, typically defined as those with bipolar disorder not

gesting that patients in high-intensity/high-conflict families otherwise specified or major depressive disorder who have

may benefit most from FFT (40, 41, 47). at least one first-degree relative with bipolar I or II disorder,

also have positive responses to FFT. In a 1-year randomized

Family Interventions for Pediatric Bipolar Spectrum controlled trial, genetically predisposed children and ado-

and High-Risk Conditions lescents (ages 9–17 years) who received 12 sessions of FFT

Despite the greater uncertainty about the diagnostic (high-risk version) with or without pharmacotherapy re-

boundaries of pediatric bipolar conditions, there is a more covered more rapidly from their initial depressive symptoms,

extensive empirical basis for family interventions in this had more weeks in remission, and showed greater improvement

age group. Fristad and colleagues (49) examined 8-session in hypomania symptoms over 1 year than those who received

multifamily psychoeducational groups in which parents of brief psychoeducation with or without pharmacotherapy (47).

bipolar children had the opportunity to interact with one Studies currently underway will examine whether family in-

another. The psychoeducational material included infor- tervention is effective in delaying or preventing the onset of

mation about mood management, communication skills, bipolar I or II disorder in high-risk children.

and coping strategies to avert mood escalation. In the largest A version of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has been

pediatric study to date, 165 bipolar (70%) and depressed developed for adolescents (ages 12–18 years) with bipolar I,

40 focus.psychiatryonline.org Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015

MIKLOWITZ AND GITLIN

TABLE 2. Randomized Trials of Family-Focused Treatment (FFT) for Patients with Bipolar Disorder or High-Risk Conditions

FFT versus

Study Sample Type of Trial Clinical State Comparison Group Key Findings

Miklowitz et al. (41) 101 adults with RCT (2 years) Depressed or manic in Crisis Management 54% survival rate in FFT

bipolar I prior 3 months (CM) (2 family versus 17% in CM

psychoeducation

sessions)

Rea et al. (42) 53 adults with RCT (2–3 years) Manic episode in prior Individual therapy 36% rehospitalized in

bipolar I 3 months (21 sessions) FFT, 60% in

individual therapy

Miklowitz et al. (43) 100 adults with Open (1 year) Depressed or manic CM FFT plus interpersonal

bipolar I/II with matched episode in prior 3 therapy associated

controls months with longer time to

relapse and less

depression

Miklowitz et al. (44, 45) 293 adults with RCT (1 year) Current episode of Collaborative care (3 At 1 year, 77%

bipolar I or II depression psychoeducation recovered in FFT;

sessions) or CC 65% in IPSRT; 60% in

CBT; 52% in CC;

better functioning in

FFT, CBT, and IPSRT

versus CC

Miklowitz et al. (40) 58 adolescents RCT (2 years) Mood episode in prior 3 enhanced care (EC) Adolescents in FFT

with bipolar I, 3 months; acutely or education sessions recovered from

II, or NOS subsyndromally ill depression 7 weeks

faster than

adolescents in EC

Perlick et al. (46) Caregivers of 46 RCT (4.7 Various states 8–12 session health Caregivers and patients

BD I adults, 1 months) program in FFT had decreases

year in depression

compared with

health program

Miklowitz et al. (47) 40 children RCT (1 year) Depression or TAU (1––2 sessions of Children in FFT

(ages 9–17 subthreshold manic family education) recovered from

years) symptoms depression 8 weeks

faster and spent

more time in

remission over 1 year

than children in TAU

Miklowitz et al. (39) 145 adolescents RCT (2 years) Mood episode in last 3 Enhanced care (3 No group differences

with bipolar I months; currently sessions of family in recovery or

or II (12–17 symptomatic education) recurrence; FFT

years) associated with less

severe manic

symptoms in year 2

Miklowitz et al. (48) 122 adolescents/ RCT (6 months) Attenuated psychotic Enhanced care (3 Patients in FFT had

young adults symptoms plus sessions of family greater reductions in

deterioration in education) positive symptoms;

functioning Patients over age 19

showed better

functioning in FFT

II, or not otherwise specified disorder (52). DBT was modeled were randomly assigned to DBT (N=14) or a less-intensive

as a 1-year treatment consisting of 18 family skills training psychosocial treatment condition (N=6). All participants re-

(conducted with individual family units) and 18 individual ceived medication management as well. Adolescents who

skills sessions. DBT is a cognitive-behavioral therapy that received DBT had less severe depressive symptoms and more

incorporates components of Eastern philosophy (e.g., mind- improvement in suicidal ideation over the year; they also

fulness meditation) to enhance emotion regulation, mindful evidenced more weeks in remission (52).

awareness, distress tolerance, and interpersonal skills. In There are some clues as to what variables are associated

a 20-subject trial with a 2:1 randomization ratio, adolescents with a positive response to family interventions versus usual

Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015 focus.psychiatryonline.org 41

PSYCHOSOCIAL APPROACHES TO THE TREATMENT OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

care in pediatric bipolar patients, including family expressed A Comparison of Therapy Approaches: the

emotion (53), more severe parental depression (51), and greater STEP-BD Study

child impairment at baseline (54). Currently, we do not know A significant limitation of the bipolar psychotherapy litera-

what patient or family attributes predict a stronger response ture is the lack of controlled comparisons of one specialty

to family versus individual CBT or group psychoeducation, treatment to another. The Systematic Treatment Enhance-

a fertile area for future research. ment Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) recruited

293 patients in a depressed phase of bipolar I or II disorder

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) from 15 sites, and randomly assigned these patients to 1) one

The interpersonal psychotherapy of depression, originally of three intensive psychosocial treatments (up to 30 sessions

developed as a comparison to CBT in the Treatments for of FFT, IPSRT, or CBT over 9 months) or 2) a 3-session

Depression Collaborative Research Program (55) has been control treatment called collaborative care (CC). All patients

adapted for bipolar disorder. In both traditional IPT and received protocol pharmacotherapy (mood stabilizers or

IPSRT, clinicians assist patients in resolving issues related to antipsychotics with or without an SSRI or buproprion). Over

grief, role transitions (e.g., divorce or separation), role dis- 1 year, being in any of the intensive psychotherapies was

putes (e.g., marital or family conflict), or interpersonal deficits associated with more frequent (and more rapid) recovery

(e.g., repetitive, self-defeating behavior patterns in relation- from depression and better psychosocial functioning than

ships). In IPSRT, strategies to enhance social and circadian being in the CC treatment, but there were no statistical

rhythm regularity are integrated into interpersonal problem- differences among the intensive treatments (see Table 2 for

solving (56). Indeed, psychosocial events that disrupt daily or recovery rates) (44, 45). Patients in the intensive treatment

nightly routines such as when a person sleeps, wakes, eats, or were 1.6 times more likely than patients in CC to be clinically

exercises have repeatedly been found to precipitate episodes well in any given month of the study.

of mood disorder (21, 57). A reanalysis of STEP-BD data (61) revealed that having

In the largest trial of IPSRT (58), 175 patients were ran- a lifetime history of an anxiety disorder was a significant

domly assigned during an acute episode of mania, de- predictor of differential response to intensive therapy versus

pression, or mixed illness to IPSRT or intensive clinical brief treatment. Among patients with lifetime anxiety dis-

management (ICM, a psychoeducational control therapy), orders (N=177), the number needed to treat to observe

both with protocol-based pharmacotherapy. Once patients a difference in intensive therapy versus CC was 5.88 (small-

had stabilized (minimum 4 weeks of stability) from their acute to-medium effect). Among patients without a history of

episode, they were rerandomized to IPSRT or ICM, with bi- anxiety disorder (N=92), the NNT to observe a difference in

weekly and then monthly sessions for up to 2 years. Thus, four intensive therapy versus CC was 50.0 (minimal effect). This

treatment strategies were formed. The 2-year recurrence is a clinically useful finding in that pharmacotherapy for

rates were: 41% for IPSRT followed by IPSRT, 41% for IPSRT comorbid anxiety disorders usually includes SSRIs that

followed by ICM, 28% for ICM followed by ICM, and 63% for can theoretically increase the risk of affective switches in

ICM followed by IPSRT. IPSRT in the acute phase was as- bipolar patients. The STEP-BD study suggests that psy-

sociated with a longer time to recurrence in the maintenance chotherapy is a vital part of the effort to stabilize episodes of

phase than ICM (58). Moreover, patients in IPSRT showed bipolar depression, particularly among patients with anxiety

better occupational functioning during acute treatment than comorbidity. Furthermore, patients with acute depression

those in ICM (59). and anxiety may require more intensive psychotherapy than

Interestingly, patients who received IPSRT acutely were is typically offered in community mental health centers.

more able to stabilize their social routines and sleep/wake

cycles during acute treatment than those in ICM. Thus,

QUESTIONS AND CONTROVERSIES

acute stabilization of sleep/wake rhythms may have down-

stream effects on the prevention of future mood instability Despite the increasing number, variety, and sophistication of

(60). It is less clear why rates of recurrence were highest in trials of psychotherapy for bipolar disorder over the past

those patients who switched from ICM to IPSRT for the decade, we are left with fairly simple conclusions. First,

maintenance phase. psychotherapy is an effective adjunct to pharmacotherapy in

IPSRT may have “stand-alone” effects for patients with the postepisode or remitted phases of bipolar disorder, with

bipolar II disorder. In a small trial for acute bipolar II de- significant evidence for several forms of family intervention,

pression (60), 25 patients were randomly assigned to que- group psychoeducation, IPSRT, and CBT. These treatments

tiapine monotherapy (beginning at 25 mg and increasing to focus on illness management (psychoeducation) and, to a

300 mg) or IPSRT monotherapy. Over 12 weeks, both groups lesser extent, interpersonal skill training. Treatments found

improved equally in depression scores, although absolute to be more effective than usual care are usually 12 or more

response rates were low (27%–29%). Future studies should sessions and last at least 4–6 months.

examine whether there is an additive effect of combining Psychotherapies that have an effect on recurrence rates

IPSRT with a second-generation antipsychotic or mood sta- also reduce hospitalization days, suggesting economic ben-

bilizer in the acute treatment of bipolar depression. efits. For example, one study of FFT found that patients with

42 focus.psychiatryonline.org Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015

MIKLOWITZ AND GITLIN

bipolar disorder were less likely to relapse over 2 years than A related issue is the importance of measuring changes in

patients in comparably intensive individual psychoeducation neural processes from before to after psychosocial treat-

and were less likely to require hospitalization when they did ments. For example, using a repeated measure neuroim-

relapse (42). In the first Barcelona study (32), structured aging design, one could examine whether patients with

psychoeducation groups were associated with a cost savings bipolar disorder show decreases in amygdala activation and

of approximately $6,500 per patient over 5 years (62). The increases in dorsolateral or ventrolateral prefrontal cortical

“price point” at which psychotherapies pay for themselves in activation when viewing negative facial stimuli from before

terms of illness or treatment cost savings (e.g., reductions in to after psychotherapy. Integrating the study of psycho-

costs of medications, lost days from work, insurance copays) therapy with brain imaging techniques may also help de-

will be of interest to patients, clinicians, and health care termine what patients are the best candidates for intensive

administrators, but we are far from determining how this therapy. A pilot study found that amygdala hyperactivation

price point differs across settings, age groups, or clinical when viewing fearful faces predicted the degree of response

presentations. to FFT versus TAU in children at high risk for bipolar dis-

We do not know what forms of psychotherapy are the order (64).

most effective for different phases of illness. Studies of group

psychoeducation (e.g., 32) or CBT (28) specify up to 6

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE AUTHORS

months of remission as an entry criterion, which would

significantly reduce the number of eligible patients in many In conducting this review, we have been struck by the lack

settings. Both FFT and IPSRT include patients who have of evidence for dissemination of evidence-based psycho-

subthreshold levels of illness and make use of current therapies in clinical practice with bipolar patients. Few of

symptoms as a teaching tool for defining prodromal symp- the available treatments are being implemented at the com-

tom states. Some patients may only need a brief period of munity level, in part because of the difficulty in accessing

psychoeducation and support to help make sense of their training and supervision from experts. Treatment manuals

recent mood episode and do not need longer-term therapy; that are easy to obtain and digest, followed by low-cost su-

patients who respond quickly to medications may be in this pervision of training cases, will be needed before treatments

group. The role of comorbid disorders other than anxiety, can be disseminated on a larger scale. Computer-assisted

including substance abuse or personality disorders, in learning methods, such as webinars (instead of weekend

specifying the type and frequency of treatment deserves workshops), online methods of supervision (e.g., chat rooms),

study. and clinician- or patient-administered measures of treatment

We know relatively little about “mediating variables” or fidelity (rather than supervisory tape viewing) will all be

change mechanisms responsible for why patients improve in useful in reducing training costs (65). These methods, how-

one treatment versus another. Ideally, a study of mediating ever, may be less satisfying to learners and may affect their

mechanisms would compare two or three forms of intensive motivation.

psychotherapy after an acute episode and measure presumed In some community mental health centers, training one

mediators at baseline, midtreatment, and after treatment to highly motivated clinician to “champion” the treatment and

determine whether changes in the mediator precede changes train others (the “train the trainer” model) can be of im-

in symptoms or functioning. An example in FFT is the study mense help in encouraging the broader adoption of novel

of Simoneau et al. (63), who measured family interactional psychotherapy methods (65). In community care, admin-

behavior in laboratory problem-solving tasks before and after istrators will have to provide individual clinicians with re-

FFT or after brief psychoeducation. Adult bipolar patients lease time to obtain this specialized level of training.

showed greater increases in positive verbal and nonverbal Clinicians need to adapt the existing treatment manuals

behavior from pretreatment to posttreatment in FFT than in to their practice settings, taking into account the treatment

the brief treatment. Moreover, these changes in interactional framework normally used in that setting. So, for example,

behavior predicted the degree of improvement in mood symp- a clinic in which the majority of practitioners are psycho-

toms among patients over a 9-month treatment interval. Be- analytically trained may more easily adopt IPSRT than CBT

cause it only measured family interactions at two time points, or FFT. Moreover, clinicians may work in settings in which

this study falls short of showing that changes in family behavior patients are not fluent in English, structured diagnostic

are causally related to changes in patients’ symptoms. None- interviews are not considered cost-effective, psychiatric med-

theless, identifying correlates of symptom change at the cog- ications are dispensed by a general practitioner, or therapy

nitive, emotional, or interpersonal levels may give us clues as to protocols that exceed 6–8 sessions are not economically

what treatments are the most powerful in bringing about feasible. Fortunately, certain treatments, including FFT and

meaningful clinical change and how to make these treatments IPSRT, have modules that can be given separately from the

more efficient. In the same vein, the ability of pharmacolog- full protocols (e.g., prodromal symptom monitoring, relapse

ical agents to change specific biological markers (e.g., brain- prevention planning, social rhythm tracking and stabiliza-

derived neurotrophic factor) may eventually guide our choice tion, family communication training) and implemented as

of drug treatments. stand-alone strategies.

Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015 focus.psychiatryonline.org 43

PSYCHOSOCIAL APPROACHES TO THE TREATMENT OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

Web-centered treatment, in which all components of an of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey

intervention are delivered through an interactive website, replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64:543–552

2. Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA,

is becoming increasingly available (65). An online self-care

Viana MC, Andrade LH, Hu C, Karam EG, Ladea M, Medina-Mora

program, “Living with Bipolar,” successfully engaged patients ME, Ono Y, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Wells JE, Zarkov Z: Preva-

and was associated with higher quality of life scores than a lence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world

waitlist control (66). Another program, bipolarcaregivers.org, mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68:

was useful to caregivers in navigating the complexities of bi- 241–251

3. Merikangas KR, Cui L, Kattan G, Carlson GA, Youngstrom EA,

polar disorder and the mental health system. It was less useful

Angst J: Mania with and without depression in a community

to caregivers of highly chronic patients or those who had com- sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69:943–951

plex family problems (67). Further evaluation of online psycho- 4. Van Meter AR, Moreira AL, Youngstrom EA: Meta-analysis of

education, either as an adjunct to evidence-based psychosocial epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psy-

treatments or as a substitute for them, is clearly needed. chiatry 2011; 72:1250–1256

5. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Wisniewski

Finally, future research must determine the best point in

SR, Gyulai L, Friedman ES, Bowden CL, Fossey MD, Ostacher MJ,

illness development to begin intervening with psychosocial Ketter TA, Patel J, Hauser P, Rapport D, Martinez JM, Allen MH,

therapy, and at what level of intensity. Treatment focused on Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Dennehy EB, Thase ME: Effectiveness of

the earliest symptom phases may interrupt neurotoxic pro- adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J

cesses of the illness and enhance long-term outcomes (68). Med 2007; 356:1711–1722

6. Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, Hammen C: Relapse and im-

Early intervention may be most effective if it is successful in

pairment in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1635–

modifying biomarkers or psychosocial risk processes that 1640

are dysregulated prior to illness onset. 7. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, Marangell LB, Zhang H, Wisniewski

The timing and duration of early interventions, however, SR, Ketter TA, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Gyulai L, Reilly-Harrington

should not be solely based on their costs or presumed effi- NA, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS, Thase ME: Predictors of recurrence

in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treat-

cacy at the group level. Early interventions must also be

ment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J

personalized. Children or adolescents with early signs of Psychiatry 2006; 163:217–224

bipolar disorder are not always motivated for treatment, nor 8. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-depressive illness, 2nd ed. New

are their parents necessarily invested in preventing a disor- York, Oxford University Press, 2007

der that may not develop anyway. Targeted interventions 9. Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Sokolski K, Hammen C, Altshuler LL: Sub-

syndromal depressive symptoms after symptomatic recovery from

that focus on disorders that herald the development of bi-

mania are associated with delayed functional recovery. J Clin

polar disorder in genetically susceptible children, such as Psychiatry 2011; 72:692–697

anxiety disorders, ADHD, conduct disorder, depression, or 10. Altshuler LL, Post RM, Black DO, Keck PEJ Jr, Nolen WA, Frye

substance/alcohol abuse, may be seen as more relevant and MA, Suppes T, Grunze H, Kupka RW, Leverich GS, McElroy SL,

acceptable to patients and parents. Finally, early interventions Walden J, Mintz J: Subsyndromal depressive symptoms are as-

sociated with functional impairment in patients with bipolar dis-

may achieve considerable effects by building on resilience

order: results of a large, multisite study. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:

factors in patients, families, or even communities, such as by 1551–1560

increasing community awareness of treatment options for 11. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Coryell W, Leon AC, Maser JD,

depression and bipolar disorder (69). Solomon DA: Residual symptom recovery from major affective epi-

sodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65:386–394

AUTHOR AND ARTICLE INFORMATION

12. Weinstock LM, Miller IW: Psychosocial predictors of mood

David J. Miklowitz, Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of Cal- symptoms 1 year after acute phase treatment of bipolar I disorder.

ifornia, Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA Compr Psychiatry 2010; 51:497–503

Michael J. Gitlin, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of California, 13. Scott J, Colom F, Vieta E: A meta-analysis of relapse rates with

Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA adjunctive psychological therapies compared to usual psychiatric

Address correspondence to David J. Miklowitz, Ph.D., Division of Child treatment for bipolar disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol

and Adolescent Psychiatry, UCLA Semel Institute Room 58-217, David 2007; 10:123–129

Geffen School of Medicine, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 14. Swartz HA: Family-focused therapy study raises new questions.

90024-1759; e-mail: dmiklowitz@mednet.ucla.edu Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171:603–606

15. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Beaulieu S, Alda

Dr. Miklowitz has received research funding from the National Institute

M, O’Donovan C, Macqueen G, McIntyre RS, Sharma V, Ravindran

of Mental Health, the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia

A, Young LT, Milev R, Bond DJ, Frey BN, Goldstein BI, Lafer B,

and Depression, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the

Birmaher B, Ha K, Nolen WA, Berk M: Canadian Network for

Attias Family Foundation, the Danny Alberts Foundation, the Carl and

Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International So-

Roberta Deutsch Foundation, the Kayne Family Foundation, and the

ciety for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT

Knapp Foundation; and book royalties from Guilford Press and John

guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder:

Wiley and Sons. Dr. Gitlin has received honoraria from Otsuka and

update 2013. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15:1–44

Bristol Myers Squibb.

16. Goodwin GM, Consensus Group of the British Association for

Psychopharmacology: Evidence-based guidelines for treating bi-

REFERENCES polar disorder: Revised second edition–recommendations from the

1. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psycho-

RMA, Petukhova M, Kessler RC: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence pharmacology. 2009;23:346–388.

44 focus.psychiatryonline.org Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015

MIKLOWITZ AND GITLIN

17. Hammen C, Gitlin M: Stress reactivity in bipolar patients and its 35. Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, Glick H, Kinosian B,

relation to prior history of disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: Altshuler L, Beresford T, Kilbourne AM, Sajatovic M; Cooperative

856–857 Studies Program 430 Study Team: Collaborative care for bipolar

18. Johnson SL: Life events in bipolar disorder: towards more specific disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs.

models. Clin Psychol Rev 2005; 25:1008–1027 Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57:937–945

19. Dienes KA, Hammen C, Henry RM, Cohen AN, Daley SE: The 36. Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, Unützer J, Operskalski B: Long-

stress sensitization hypothesis: understanding the course of bi- term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bi-

polar disorder. J Affect Disord 2006; 95:43–49 polar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:500–508

20. Gilman SE, Ni MY, Dunn EC, Breslau J, McLaughlin KA, Smoller 37. Torrent C, Bonnin CdelM, Martínez-Arán A, Valle J, Amann BL,

JW, Perlis RH: Contributions of the social environment to first- González-Pinto A, Crespo JM, Ibáñez Á, Garcia-Portilla MP,

onset and recurrent mania. Mol Psychiatry 2014; [Epub ahead of Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Arango C, Colom F, Solé B, Pacchiarotti I,

print] Rosa AR, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Anaya C, Fernández P, Landín-

21. Malkoff-Schwartz S, Frank E, Anderson BP, Hlastala SA, Luther Romero R, Alonso-Lana S, Ortiz-Gil J, Segura B, Barbeito S, Vega P,

JF, Sherrill JT, Houck PR, Kupfer DJ: Social rhythm disruption Fernández M, Ugarte A, Subirà M, Cerrillo E, Custal N, Menchón

and stressful life events in the onset of bipolar and unipolar epi- JM, Saiz-Ruiz J, Rodao JM, Isella S, Alegría A, Al-Halabi S, Bobes J,

sodes. Psychol Med 2000; 30:1005–1016 Galván G, Saiz PA, Balanzá-Martínez V, Selva G, Fuentes-Durá I,

22. Johnson SL, Edge MD, Holmes MK, Carver CS: The behavioral Correa P, Mayoral M, Chiclana G, Merchan-Naranjo J, Rapado-

activation system and mania. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2012; 8: Castro M, Salamero M, Vieta E: Efficacy of functional remediation in

243–267 bipolar disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled study. Am J

23. Miklowitz DJ, Johnson SL: Social and familial risk factors in bi- Psychiatry 2013; 170:852–859

polar disorder: basic processes and relevant interventions. Clin 38. Miklowitz DJ: Bipolar disorder: a family-focused treatment ap-

Psychol Sci Pract 2009; 16:281–296 proach, 2nd ed. New York, NY, Guilford Press, 2008

24. Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Keck PEJ Jr, 39. Miklowitz DJ, Schneck CD, George EL, Taylor DO, Sugar CA,

McElroy SL, Denicoff KD, Obrocea G, Nolen WA, Kupka R, Birmaher B, Kowatch RA, DelBello MP, Axelson DA: Pharmaco-

Walden J, Grunze H, Perez S, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM: Factors therapy and family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar

associated with suicide attempts in 648 patients with bipolar dis- I and II disorders: a 2-year randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry

order in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. J Clin Psychi- 2014; 171:658–667

atry 2003; 64:506–515 40. Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, George EL, Taylor DO,

25. Leverich GS, Post RM, Keck PEJ Jr, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Kupka Schneck CD, Beresford CA, Dickinson LM, Craighead WE, Brent

RW, Nolen WA, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Grunze H, Denicoff K, DA: Family-focused treatment for adolescents with bipolar disor-

Moravec MK, Luckenbaugh D: The poor prognosis of childhood- der: results of a 2-year randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry

onset bipolar disorder. J Pediatr 2007; 150:485–490 2008; 65:1053–1061

26. Miklowitz DJ, Scott J: Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disor- 41. Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Suddath RL:

der: cost-effectiveness, mediating mechanisms, and future direc- A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and

tions. Bipolar Disord 2009; 11(Suppl 2):110–122 pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disor-

27. Muralidharan A, Miklowitz DJ, Craighead WE: Psychosocial der. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:904–912

treatments for bipolar disorder, in A Guide to Treatments That 42. Rea MM, Tompson MC, Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Hwang S,

Work, 3rd ed. Edited by Nathan PE, Gorman JM. New York, Mintz J: Family-focused treatment versus individual treatment for

Oxford University in press. bipolar disorder: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult

28. Lam DH, Hayward P, Watkins ER, Wright K, Sham P: Relapse Clin Psychol 2003; 71:482–492

prevention in patients with bipolar disorder: cognitive therapy 43. Miklowitz DJ, Richards JA, George EL, Frank E, Suddath RL,

outcome after 2 years. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:324–329 Powell KB, Sacher JA: Integrated family and individual therapy for

29. Scott J: Psychotherapy for bipolar disorders—efficacy and effec- bipolar disorder: results of a treatment development study. J Clin

tiveness. J Psychopharmacol 2006; 20(Suppl):46–50 Psychiatry 2003; 64:182–191

30. Parikh SV, Zaretsky A, Beaulieu S, Yatham LN, Young LT, Patelis- 44. Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Kogan

Siotis I, Macqueen GM, Levitt A, Arenovich T, Cervantes P, JN, Sachs GS, Thase ME, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Ostacher

Velyvis V, Kennedy SH, Streiner DL: A randomized controlled trial MJ, Patel J, Thomas MR, Araga M, Gonzalez JM, Wisniewski SR.

of psychoeducation or cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar Intensive psychosocial intervention enhances functioning in patients

disorder: a Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety treatments with bipolar depression: results from a 9-month randomized con-

(CANMAT) study [CME]. J Clin Psychiatry 2012; 73:803–810 trolled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1340–1347

31. Meyer TD, Hautzinger M: Cognitive behaviour therapy and sup- 45. Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Wisniewski

portive therapy for bipolar disorders: relapse rates for treatment SR, Kogan JN, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Gyulai L,

period and 2-year follow-up. Psychol Med 2012; 42:1429–1439 Araga M, Gonzalez JM, Shirley ER, Thase ME, Sachs GS: Psychosocial

32. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the

Benabarre A, Torrent C, Comes M, Corbella B, Parramon G, Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry

Corominas J: A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psy- 2007; 64:419–426

choeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients 46. Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Lopez N, Chou J, Kalvin C, Adzhiashvili V,

whose disease is in remission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60: Aronson A: Family-focused treatment for caregivers of patients with

402–407 bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2010; 12:627–637

33. Miklowitz DJ, Goodwin GM, Bauer MS, Geddes JR: Common and 47. Miklowitz DJ, Schneck CD, Singh MK, Taylor DO, George EL,

specific elements of psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder: Cosgrove VE, Howe ME, Dickinson LM, Garber J, Chang KD:

a survey of clinicians participating in randomized trials. J Psy- Early intervention for symptomatic youth at risk for bipolar dis-

chiatr Pract 2008; 14:77–85 order: a randomized trial of family-focused therapy. J Am Acad

34. Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013; 52:121–131

Martínez-Arán A: A randomized trial on the efficacy of group 48. Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, Schlosser DA, Addington J, Candan

psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorder: A five year KA, Marshall C, Domingues I, Walsh BC, Zinberg JL, De Silva SD,

follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 194:260–265 Friedman-Yakoobian M, Cannon TD: Family-focused treatment

Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015 focus.psychiatryonline.org 45

PSYCHOSOCIAL APPROACHES TO THE TREATMENT OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

for adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis: results functioning in patients with bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry

of a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014; 2008; 165:1559–1565

53:848–858 60. Swartz HA, Frank E, Cheng Y: A randomized pilot study of psy-

49. Fristad MA, Verducci JS, Walters K, Young ME. Impact of mul- chotherapy and quetiapine for the acute treatment of bipolar II

tifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy in treating children depression. Bipolar Disord 2012; 14:211–216

aged 8 to 12 years with mood disorders. Archives of General 61. Deckersbach T, Peters A, Sylvia L, Urdahl A, Vieira da Silva

Psychiatry 2009; 66:1013–1021 Magalhaes P, Otto MW, Frank E, Miklowitz D, Berk M, Kinrys G,

50. Mendenhall AN, Fristad MA, Early TJ: Factors influencing service Nierenberg A: Do comorbid anxiety disorders moderate the effects

utilization and mood symptom severity in children with mood of psychotherapy for bipolar disorder? Results from STEP-BD. Am

disorders: effects of multifamily psychoeducation groups (MFPGs). J Psychiatry 2014; 171:178–186

J Consult Clin Psychol 2009; 77:463–473 62. Scott J, Colom F, Popova E, Benabarre A, Cruz N, Valenti M,

51. West AE, Weinstein SM, Peters AT, Katz AC, Henry DB, Cruz RA, Goikolea JM, Sánchez-Moreno J, Asenjo MA, Vieta E: Long-term

Pavuluri MN: Child- and family-focused cognitive-behavioral mental health resource utilization and cost of care following group

therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical tri- psychoeducation or unstructured group support for bipolar dis-

al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (in press) orders: a cost-benefit analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70:378–

52. Goldstein TR, Fersch-Podrat RK, Rivera M, Axelson DA, Merranko J, 386

Yu H, Brent D, Birmaher B: Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for 63. Simoneau TL, Miklowitz DJ, Richards JA, Saleem R, George EL:

adolescents with bipolar disorder: results from a pilot randomized Bipolar disorder and family communication: effects of a psycho-

trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2014; [Epub ahead of print] educational treatment program. J Abnorm Psychol 1999; 108:

53. Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, 588–597

Sullivan AE, Dickinson LM, Birmaher B: Expressed emotion mod- 64. Garrett AS, Miklowitz DJ, Howe ME, Singh MK, Acquaye TK,

erates the effects of family-focused treatment for bipolar adoles- Hawkey CG, Glover GH, Reiss AL, Chang KD: Changes in brain

cents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:643–651 function associated with family focused therapy for youth at high

54. MacPherson HA, Algorta GP, Mendenhall AN, Fields BW, Fristad risk for bipolar disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psy-

MA. Predictors and moderators in the randomized trial of multi- chiatry 2014; 56C:215–220

family psychoeducational psychotherapy for childhood mood dis- 65. Fairburn CG, Patel V: The global dissemination of psychological

orders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:459–472. treatments: a road map for research and practice. Am J Psychiatry

55. Elkin I, Gibbons RD, Shea MT, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT, Pilkonis 2014; 171:495–498

PA, Hedeker D: Initial severity and differential treatment outcome 66. Todd NJ, Jones SH, Hart A, Lobban FA: A web-based self-

in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of De- management intervention for Bipolar Disorder ‘Living with Bi-

pression Collaborative Research Program. J Consult Clin Psychol polar’: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord

1995; 63:841–847 2014; 169:21–29

56. Frank E: Treating bipolar disorder: A clinician’s guide to in- 67. Berk L, Berk M, Dodd S, Kelly C, Cvetkovski S, Jorm AF: Evalu-

terpersonal and social rhythm therapy. New York, Guilford Pub- ation of the acceptability and usefulness of an information website

lications, 2005 for caregivers of people with bipolar disorder. BMC Med 2013; 11:

57. Harvey AG: Sleep and circadian functioning: critical mechanisms 162

in the mood disorders? Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2011; 7:297–319 68. Post RM, Kowatch RA: The health care crisis of childhood-onset

58. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, bipolar illness: some recommendations for its amelioration. J Clin

Fagiolini AM, Grochocinski V, Houck P, Scott J, Thompson W, Psychiatry 2006; 67:115–125

Monk T: Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm 69. Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, Dixon EL, Tang L, Gilmore J,

therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry Sherbourne C, Ngo VK, Ong MK, Stockdale S, Ramos E, Belin TR,

2005; 62:996–1004 Miranda J: Community-partnered cluster-randomized compara-

59. Frank E, Soreca I, Swartz HA, Fagiolini AM, Mallinger AG, Thase tive effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or

ME, Grochocinski VJ, Houck PR, Kupfer DJ: The role of in- resources for services to address depression disparities. J Gen

terpersonal and social rhythm therapy in improving occupational Intern Med 2013; 28:1268–1278

46 focus.psychiatryonline.org Focus Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 2015

You might also like

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument16 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptMuhammad NizarNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Treatments For Bipolar Depression A 1-Year Randomized Trial From The Systematic Treatment Enhanced Program PDFDocument9 pagesPsychosocial Treatments For Bipolar Depression A 1-Year Randomized Trial From The Systematic Treatment Enhanced Program PDFMichael Spike LevinNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Disorder Treatment: Psychosocial Therapies Augment Medication to Improve Outcomes and Reduce DisabilityDocument26 pagesBipolar Disorder Treatment: Psychosocial Therapies Augment Medication to Improve Outcomes and Reduce DisabilityChristine EnriquezNo ratings yet

- DBT For Bipolar DisorderDocument26 pagesDBT For Bipolar DisorderWasim RashidNo ratings yet

- Who Paper Depression WFMH 2012Document4 pagesWho Paper Depression WFMH 2012antoniodhani.adNo ratings yet

- Comparing Mindfulness Based Cognitive THDocument5 pagesComparing Mindfulness Based Cognitive THolgasacristan316No ratings yet

- Warih - Konas Bipolar - 2015 - The Needs of Bipolar Disorder Psychoeducation in Family MembersDocument10 pagesWarih - Konas Bipolar - 2015 - The Needs of Bipolar Disorder Psychoeducation in Family MembersAnonymous 2T5Nk6No ratings yet

- A Review of Empirically Supported Psychological Therapies For Mood Disorders in AdultsDocument43 pagesA Review of Empirically Supported Psychological Therapies For Mood Disorders in AdultssaNo ratings yet

- PP + CBTDocument8 pagesPP + CBTLev FyodorNo ratings yet

- Rou Saud 2007Document11 pagesRou Saud 2007healliz36912No ratings yet

- !jhanghir-2017 MF and A Lot of Disorders in Drug AddictsDocument11 pages!jhanghir-2017 MF and A Lot of Disorders in Drug AddictsmatalacurNo ratings yet

- Psychological interventions for bipolar disorderDocument9 pagesPsychological interventions for bipolar disorderFausiah Ulva MNo ratings yet

- CBT for Bipolar Disorders ExplainedDocument3 pagesCBT for Bipolar Disorders ExplainedNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Admin, ZIK LECTURE JOURNAL-82-91Document10 pagesAdmin, ZIK LECTURE JOURNAL-82-91ElenaNo ratings yet

- Holl On 2002Document39 pagesHoll On 2002Nabella Martha AnisaNo ratings yet

- Preventing Progression To FEPDocument11 pagesPreventing Progression To FEPsaurav.das2030No ratings yet

- ABPSY 1 Mood DisordesDocument19 pagesABPSY 1 Mood DisordesCarm RiveraNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Psychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder in Adults: A Review of The EvidenceDocument26 pagesHHS Public Access: Psychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder in Adults: A Review of The EvidenceNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Research Case StudyDocument3 pagesA Qualitative Research Case StudyAndrea AtonducanNo ratings yet

- Binge-Eating Disorder in AdultsDocument19 pagesBinge-Eating Disorder in AdultsJaimeErGañanNo ratings yet

- Depresion NhsDocument10 pagesDepresion NhsMauroNo ratings yet

- Overview of prevention and treatment for pediatric depressionDocument31 pagesOverview of prevention and treatment for pediatric depressionLauraNo ratings yet

- Depression and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Special ArticleDocument5 pagesDepression and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Special ArticleLuciano RestrepoNo ratings yet

- Depression and Psychodynamic PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesDepression and Psychodynamic PsychotherapyRija ChoudhryNo ratings yet

- CBT in Cancer Patients ST PDFDocument16 pagesCBT in Cancer Patients ST PDFMerve ApaydınNo ratings yet

- Distimia y Apatía. Diagnóstico y TratamientoDocument8 pagesDistimia y Apatía. Diagnóstico y TratamientoArmando RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Appi Ajp 162 12 2220Document13 pagesAppi Ajp 162 12 2220LosineKrishnaNo ratings yet

- A Summary of Biomedical Aspects of Mood DisordersDocument93 pagesA Summary of Biomedical Aspects of Mood DisordersFerdinand PodimanNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument12 pagesRetrieveAyla CoberoNo ratings yet

- Antidepressants in Bipolar Depression An Enduring ControversyDocument6 pagesAntidepressants in Bipolar Depression An Enduring ControversyIzzyinOzzieNo ratings yet

- 2.psilocybin-Assisted Therapy For Depression A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Human StudiesDocument16 pages2.psilocybin-Assisted Therapy For Depression A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Human StudiesMarcos MouraNo ratings yet

- מאמר 2019Document12 pagesמאמר 2019LIMORNo ratings yet

- Conclusion DepressionDocument29 pagesConclusion Depressionkainnat naeemNo ratings yet

- Beck Cognitive Theory of DepressionDocument5 pagesBeck Cognitive Theory of DepressionSaima BabarNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy For Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A)Document8 pagesInterpersonal Psychotherapy For Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A)Wiwin Apsari WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 20 01555 v2Document16 pagesIjerph 20 01555 v2Diana DionisioNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11920 019 1117 XDocument10 pages10.1007@s11920 019 1117 Xyalocim666No ratings yet

- Combination PharmacotherapyDocument18 pagesCombination Pharmacotherapydo leeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Gangguan Bipolar PDFDocument7 pagesJurnal Gangguan Bipolar PDFasep budiyantoNo ratings yet

- Rummel Kluge 2008Document11 pagesRummel Kluge 2008Patricia RivasNo ratings yet

- WangDocument9 pagesWangIolanda PălimaruNo ratings yet

- Psychodynamic Treatment of DepressionDocument19 pagesPsychodynamic Treatment of DepressionJuan Guillermo Manrique Lopez100% (1)

- Schizophrenia in Adults Maintenance Therapy and Side Effect ManagementDocument46 pagesSchizophrenia in Adults Maintenance Therapy and Side Effect ManagementIgnacioNo ratings yet

- Fedor Off 2001Document14 pagesFedor Off 2001Gustavo PaniaguaNo ratings yet

- General Hospital Psychiatry Study on Positive Emotion Regulation InterventionDocument8 pagesGeneral Hospital Psychiatry Study on Positive Emotion Regulation InterventionFranciscoNo ratings yet

- STPP Somatic AllDocument9 pagesSTPP Somatic AllMario ColliNo ratings yet

- Depression: A Global Public Health ConcernDocument3 pagesDepression: A Global Public Health ConcernanalailaNo ratings yet

- A Review of Bipolar Disorder Among Adults PDFDocument13 pagesA Review of Bipolar Disorder Among Adults PDFNadyaNo ratings yet

- D. Barlow - Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment For Panic Disorder Current StatusDocument16 pagesD. Barlow - Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment For Panic Disorder Current StatusArmando ValladaresNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 20 00091 v2Document11 pagesIjerph 20 00091 v2christian-arcayos-2035No ratings yet

- The Impact of Well - Being Therapy On Symptoms of DepressionDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Well - Being Therapy On Symptoms of DepressionEstefany ReyesNo ratings yet

- Psic EdDocument27 pagesPsic EdNicolás Robertino LombardiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Bipolar Affective DisorderDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of Bipolar Affective Disorderafmzwflmdnxfeb100% (1)

- Lynch Et Al (2013)Document17 pagesLynch Et Al (2013)Valerie Walker LagosNo ratings yet

- Adjunctive Psychotherapy For Bipolar DisorderDocument10 pagesAdjunctive Psychotherapy For Bipolar DisorderAgustin NunezNo ratings yet

- Jiwa 3 PDFDocument7 pagesJiwa 3 PDFsondiNo ratings yet

- Antidepressants in Bipolar Depression: An Enduring ControversyDocument7 pagesAntidepressants in Bipolar Depression: An Enduring ControversyAgusNo ratings yet

- Efecto de Programa de 12 Sesiones de Psicoeducación, Mindfulness Basada en Terapia Cognitiva, Remediación Funcional para Trastornos BipolararesDocument9 pagesEfecto de Programa de 12 Sesiones de Psicoeducación, Mindfulness Basada en Terapia Cognitiva, Remediación Funcional para Trastornos BipolararesGiorgio AgostiniNo ratings yet

- SR Inc 1Document9 pagesSR Inc 1DWIINDAHNo ratings yet

- Multimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionFrom EverandMultimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionNo ratings yet

- TeksDocument1 pageTeksNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics Service After Covid-19 Pandemic: EditorialDocument1 pageObstetrics Service After Covid-19 Pandemic: EditorialNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics Service After Covid-19 Pandemic: EditorialDocument1 pageObstetrics Service After Covid-19 Pandemic: EditorialNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension During PregnancyDocument9 pagesHypertension During PregnancyNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics Service After Covid-19 Pandemic: EditorialDocument1 pageObstetrics Service After Covid-19 Pandemic: EditorialNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- JR Plasenta AccretaDocument4 pagesJR Plasenta AccretaNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Wave Abstract PowerPoint TemplateDocument35 pagesBeautiful Wave Abstract PowerPoint TemplateNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Wave Abstract PowerPoint TemplateDocument35 pagesBeautiful Wave Abstract PowerPoint TemplateNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Gold 2018Document142 pagesGold 2018histoginoNo ratings yet

- DAFPUSDocument4 pagesDAFPUSNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Family-Focused Therapy For Bipolar Disorder: Reflections On 30 Years of ResearchDocument21 pagesHHS Public Access: Family-Focused Therapy For Bipolar Disorder: Reflections On 30 Years of ResearchNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Proposal FixDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Proposal FixNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension During PregnancyDocument9 pagesHypertension During PregnancyNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- JR Metildopa Untuk Antihpertensi KehamilanDocument4 pagesJR Metildopa Untuk Antihpertensi KehamilanNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Trajectories of Adherence To Mood Stabilizers in Patients With Bipolar DisorderDocument9 pagesTrajectories of Adherence To Mood Stabilizers in Patients With Bipolar DisorderNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Differences in Mood Instability in Patients With Bipolar Disorder Type I and II: A Smartphone Based StudyDocument8 pagesDifferences in Mood Instability in Patients With Bipolar Disorder Type I and II: A Smartphone Based StudyAndre PhanNo ratings yet

- Warih - Konas Bipolar - 2015 - The Needs of Bipolar Disorder Psychoeducation in Family MembersDocument10 pagesWarih - Konas Bipolar - 2015 - The Needs of Bipolar Disorder Psychoeducation in Family MembersAnonymous 2T5Nk6No ratings yet

- 2017 Article 99Document10 pages2017 Article 99Nera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral TherapyDocument20 pagesEfficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral TherapyIrfan FauziNo ratings yet

- Warih - Konas Bipolar - 2015 - The Needs of Bipolar Disorder Psychoeducation in Family MembersDocument10 pagesWarih - Konas Bipolar - 2015 - The Needs of Bipolar Disorder Psychoeducation in Family MembersAnonymous 2T5Nk6No ratings yet

- CBT for Bipolar Disorders ExplainedDocument3 pagesCBT for Bipolar Disorders ExplainedNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Psychotherapy in Bipolar DisorderDocument5 pagesThe Role of Psychotherapy in Bipolar DisorderNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder.: References ReprintsDocument9 pagesPsychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder.: References ReprintsNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy of Bipolar Disorder: A Review: Steven JonesDocument14 pagesPsychotherapy of Bipolar Disorder: A Review: Steven JonesNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Psychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder in Adults: A Review of The EvidenceDocument26 pagesHHS Public Access: Psychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder in Adults: A Review of The EvidenceNera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder: The British Journal of Psychiatry December 1995Document10 pagesPsychotherapy For Bipolar Disorder: The British Journal of Psychiatry December 1995Nera MayaditaNo ratings yet

- Excursion WorksheetDocument6 pagesExcursion Worksheetapi-348781812No ratings yet

- Larsen, J.K. (2017)Document8 pagesLarsen, J.K. (2017)Ale ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Bibliografiaactualizada de Ecografia y RadiologíaDocument2 pagesBibliografiaactualizada de Ecografia y RadiologíaKimberly NicoleNo ratings yet

- Amniotic Membrane: From Structure and Functions To Clinical ApplicationsDocument24 pagesAmniotic Membrane: From Structure and Functions To Clinical ApplicationsLim Xian NioNo ratings yet

- Epilepsy DR LindaDocument8 pagesEpilepsy DR LindaLaylaNo ratings yet

- Defic I Enc I A MultipleDocument16 pagesDefic I Enc I A MultipleEnrique GonzalvusNo ratings yet

- Drug inventory listDocument2 pagesDrug inventory listEdwin SartorioNo ratings yet

- Classification of Local AnestheticsDocument50 pagesClassification of Local AnestheticsHelen Reyes HallareNo ratings yet

- 7 BurnDocument29 pages7 BurnAlem AyahuNo ratings yet

- ATLS - Head Trauma ImodifiedDocument39 pagesATLS - Head Trauma ImodifiedSammon TareenNo ratings yet

- Complications of CastingDocument12 pagesComplications of CastingDiana Veroshini GengatharanNo ratings yet

- Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs) About Cochlear Implants: What Is A Cochlear Implant?Document2 pagesFrequently Asked Questions (Faqs) About Cochlear Implants: What Is A Cochlear Implant?Carmen Emma GouwsNo ratings yet

- Name Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailDocument8 pagesName Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailshrutiNo ratings yet

- DSD 45X46XY Mixed Gonadal Dysgenesis Long-TerDocument6 pagesDSD 45X46XY Mixed Gonadal Dysgenesis Long-TerSamuelRexyNo ratings yet

- Ivf StudyDocument1 pageIvf StudyjeliinNo ratings yet

- Hybrid Hyrax Distalizer JO PDFDocument7 pagesHybrid Hyrax Distalizer JO PDFCaTy ZamNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal Failure: Case Study #1Document9 pagesAcute Renal Failure: Case Study #1Martin Reverente0% (1)

- Lab Test Results 7 2015Document3 pagesLab Test Results 7 2015Antzee Dancee0% (1)

- Pericardial Disease EscDocument44 pagesPericardial Disease EscMelati SatriasNo ratings yet

- McDonald Criteria 2005Document2 pagesMcDonald Criteria 2005api-3828181100% (1)

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No 202Document25 pagesACOG Practice Bulletin No 202Berri RahmadhoniNo ratings yet

- Transfusion ReactionsDocument11 pagesTransfusion ReactionsBungas Arisudana50% (2)

- Day 2 Unicorn 1 1Document48 pagesDay 2 Unicorn 1 1Nancy NaeimNo ratings yet

- Phobia 101: Types, Causes and TreatmentsDocument3 pagesPhobia 101: Types, Causes and TreatmentsPau BorlagdanNo ratings yet

- Endotracheal Intubation GuideDocument4 pagesEndotracheal Intubation Guiderupali gahalianNo ratings yet

- People V Puno - AtasDocument3 pagesPeople V Puno - AtasCarlo GuiamNo ratings yet

- MSEDocument21 pagesMSEfathima1991No ratings yet

- Dr. Ali Khamis - CVDocument2 pagesDr. Ali Khamis - CVAli KhamisNo ratings yet

- Date / Time Cues Nee D Nursing Diagnosis Patient Outcome Nursing Interventions Implemen Tation EvaluationDocument3 pagesDate / Time Cues Nee D Nursing Diagnosis Patient Outcome Nursing Interventions Implemen Tation EvaluationJennifer Davis Condiman100% (1)

- Strategi Penatalaksanaan Stomatitis Aftosa RekurenDocument11 pagesStrategi Penatalaksanaan Stomatitis Aftosa RekurenPRADNJA SURYA PARAMITHANo ratings yet