Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Muriel Spark Life and Works

Uploaded by

lucrezia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

72 views2 pagesDame Muriel Spark was a renowned Scottish author who lived from 1918 to 2006. She wrote 20 novels as well as poetry and works of literary criticism. Spark had a varied life, moving from Scotland to Rhodesia as a young woman, working in British intelligence during World War 2, and eventually settling in Italy. Her 1961 novel The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie brought her considerable acclaim. Territorial Rights is one of Spark's novels that examines themes of self-deception through a group of tourists in Venice whose pasts intersect in intriguing ways.

Original Description:

Original Title

MURIEL SPARK LIFE AND WORKS

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDame Muriel Spark was a renowned Scottish author who lived from 1918 to 2006. She wrote 20 novels as well as poetry and works of literary criticism. Spark had a varied life, moving from Scotland to Rhodesia as a young woman, working in British intelligence during World War 2, and eventually settling in Italy. Her 1961 novel The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie brought her considerable acclaim. Territorial Rights is one of Spark's novels that examines themes of self-deception through a group of tourists in Venice whose pasts intersect in intriguing ways.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

72 views2 pagesMuriel Spark Life and Works

Uploaded by

lucreziaDame Muriel Spark was a renowned Scottish author who lived from 1918 to 2006. She wrote 20 novels as well as poetry and works of literary criticism. Spark had a varied life, moving from Scotland to Rhodesia as a young woman, working in British intelligence during World War 2, and eventually settling in Italy. Her 1961 novel The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie brought her considerable acclaim. Territorial Rights is one of Spark's novels that examines themes of self-deception through a group of tourists in Venice whose pasts intersect in intriguing ways.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

MURIEL

SPARK - LIFE AND WORKS

Dame Muriel Spark, DBE, lived from 1 February 1918 to 13 April 2006. She was a novelist, poet and non-

fiction author. The wider picture in Scotland at the time is set out in our Historical Timeline.

Muriel Sarah Camberg was born in Edinburgh. Her father was an engineer and her mother a music teacher.

She was educated at James Gillespie's High School for Girls, and in 1934-1935 she took a course in

"Commercial correspondence and précis writing" at Heriot-Watt College. She then worked as an English

teacher and as a secretary. One of her teachers at James Gillespie's High School was Christina Kay, who

would later become the model for the main character in Muriel Spark's The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

In 1937 Muriel married Sidney Oswald Spark, and shortly afterwards they moved together to Rhodesia,

now called Zimbabwe, where he had secured a job as a teacher. They had a son, Robin, in 1938, by which

time, Muriel had discovered her husband was a manic depressive. Muriel left her husband and son to

return to the UK where, from 1944, she worked in British Intelligence. Spark later said it had been her

intention to establish a family home in Britain, but her husband returned separately and their son was

brought up by Muriel's parents in Edinburgh.

After the Second World War, Muriel began writing under her married name, which she felt was more

memorable than her maiden name. Her first outings were into poetry and literary criticism, and in 1947 she

became editor of the Poetry Review. In 1954, following a breakdown, she converted to Roman Catholicism.

She later said this was an important step on her path towards becoming a novelist, and it was three years

later that her first novel, The Comforters, was published. Her fifth novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie,

was published in 1961 to considerable acclaim and success. In all, Muriel Spark wrote 20 novels, concluding

with The Finishing School which was published in 2004. She also published 19 further works, ranging from

collections of poetry to short stories and biographical works about authors like Emily Brontë and John

Masefield.

Muriel spent part of the 1960s living in New York. She moved to Rome in 1967, where she met the artist

and sculptor Penelope Jardine. They settled in the village of Civitella della Chiana in Tuscany, where they

lived until Muriel's death in 2006. During her career, Dame Muriel Spark had won a string of literary

awards, and in 1993 was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire for her services to

literature.

TERRITORIAL RIGHTS

Muriel Spark’s Territorial Rights is a wryly, perceptively funny novel which nevertheless has its sudden

darkly suggestive turns. By turns it is a story of pursuit, marital problems, tourist-watching, young love, old

love (and an astonishing mixture of the two), and social-political intrigue veiled in recent history, yet

involving a bloody murder and a hidden body. Territorial Rights might therefore be labeled a suspense

novel, but it is not; it is too cheeky and cheerful for that. Rather, it is a novel about jaded, eccentric people

who themselves believe in the possibility of a novel of suspense. Spark’s characters play their quirky roles

within a book which is, itself, laughing at them. Reading the novel, one senses Spark’s muted laughter and

bemused affection behind one’s own startled and delighted gasps of recognition at the human foibles she

so unerringly makes natural and almost cinematically graphic.

her basic theme is people and their various survival techniques. In this novel, Spark has a glorious rogues

gallery of characters drawn together unexpectedly by an old, nearly forgotten murder and the resultant

various forms of blackmail and subterfuge its discovery entails. Each of these characters, from the highest

to the lowest, from the richest to the poorest, has something to hide; yet they are all filled with pride as

they scramble to protect themselves from one another while also keeping blindly occupied in order to

avoid their own self-knowledge. It is to their dubious credit that each of them is successful in his or her self-

delusion. It keeps them from despair, perhaps from suicide.

This theme of the human proclivity for indulging in self-deception is given a further, typically Sparkian twist

by the impact of the novel’s title. The characters are all tourists in Venice where each has come for escape

from unpleasant reality elsewhere. Inevitably they find that there is no safety from one another, and

moreover, no larger, societal safety at all for them in a place where, as outsiders, they have no territorial

rights. They are characters whose moral lives have been built upon shifting sand, living temporarily and

precariously in a sinking city built upon water. Under these conditions, their efforts to shore up their

various prides and deceptions are both touching and hilarious. The central character, Robert Leaver, for

example, tries to save his self-esteem by turning on his philandering, pompous father and by blackmailing

his own former lover, Mark Curran, a wealthy, effete American; but Robert fools no one but himself.

Everyone around him knows he merely resents his father’s having a successful, good time with a mistress

away from his stuffy home, stuffy job, and stuffy wife. They know, too, that he envies Curran his urbanity,

his attractiveness, and his knowledge of art and architecture even more than he envies him the money he

claims to be after.

You might also like

- With Fire and Sword by Henryk Sienkiewicz - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)From EverandWith Fire and Sword by Henryk Sienkiewicz - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Insights Into Everything Through HumanitiesDocument1 pageInsights Into Everything Through HumanitiesSekkiNo ratings yet

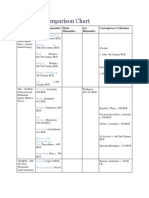

- Core Text Comparison ChartDocument4 pagesCore Text Comparison ChartLarryBajina321No ratings yet

- The History of the American Pro-Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Paris (1815-1980)From EverandThe History of the American Pro-Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Paris (1815-1980)No ratings yet

- NCEA and Their FriendsDocument5 pagesNCEA and Their FriendspghcaccNo ratings yet

- Classical Curriculum Guide: Core Western WritingsDocument2 pagesClassical Curriculum Guide: Core Western WritingsAmal MadhuNo ratings yet

- dMAC Digest Vol 7 No 1A: History Behind the Lindisfarne GospelsFrom EveranddMAC Digest Vol 7 No 1A: History Behind the Lindisfarne GospelsNo ratings yet

- Catholic "Gateway To Global Understanding"Document43 pagesCatholic "Gateway To Global Understanding"pghcaccNo ratings yet

- Gathered As One Year 3 Lesson Plan Step C - Christian ResponseDocument4 pagesGathered As One Year 3 Lesson Plan Step C - Christian Responseapi-374639707No ratings yet

- Russia’s Uncommon Prophet: Father Aleksandr Men and His TimesFrom EverandRussia’s Uncommon Prophet: Father Aleksandr Men and His TimesNo ratings yet

- History of The Church Didache Series: Final Exam 1st SemesterDocument4 pagesHistory of The Church Didache Series: Final Exam 1st SemesterFr Samuel Medley SOLTNo ratings yet

- Common Core Is Hostile To Christian and Catholic EducationDocument10 pagesCommon Core Is Hostile To Christian and Catholic EducationpghcaccNo ratings yet

- What Is The Common CoreDocument10 pagesWhat Is The Common Coreobx4everNo ratings yet

- Don Bosco Study Guide 1 PDFDocument11 pagesDon Bosco Study Guide 1 PDFUniversidad Don Bosco100% (1)

- Forty Martyrs of England and WalesDocument13 pagesForty Martyrs of England and WalesNorman HartleyNo ratings yet

- Danielson Lesson Plan 2 For Student TeachingDocument4 pagesDanielson Lesson Plan 2 For Student Teachingapi-269479291No ratings yet

- Hallelujah – The story of a musical genius and the city that brought his masterpiece to life: George Frideric Handel's Messiah in DublinFrom EverandHallelujah – The story of a musical genius and the city that brought his masterpiece to life: George Frideric Handel's Messiah in DublinRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Inferno (Translated by Nichols)Document23 pagesInferno (Translated by Nichols)kane_kane_kaneNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Anglo-Saxon Britain TimelineDocument5 pagesUnit 1 - Anglo-Saxon Britain TimelineWilfredo RamiresNo ratings yet

- Top 100 Great BooksDocument4 pagesTop 100 Great BooksKomishinNo ratings yet

- Clement of Alexandria Exhortation To The HeathenDocument39 pagesClement of Alexandria Exhortation To The HeathenСтефан ЂурићNo ratings yet

- Pope Pius VIDocument7 pagesPope Pius VImenilanjan89nLNo ratings yet

- Study Guide for The Corporal and Spiritual Works of Mercy by Mitch FinleyFrom EverandStudy Guide for The Corporal and Spiritual Works of Mercy by Mitch FinleyNo ratings yet

- Catholic Church in AustraliaDocument19 pagesCatholic Church in AustraliaAidan McCabeNo ratings yet

- Through Shakespeare's Eyes: Seeing the Catholic Presence in the PlaysFrom EverandThrough Shakespeare's Eyes: Seeing the Catholic Presence in the PlaysNo ratings yet

- The Stuarts Civil War RestorationDocument26 pagesThe Stuarts Civil War RestorationBart StewartNo ratings yet

- The Unrepentant Catholic’s Cautionary Calendar Guide to ModernityDocument147 pagesThe Unrepentant Catholic’s Cautionary Calendar Guide to Modernitympbh91No ratings yet

- Étienne Gilson, Wisdom and Love in Saint Thomas Aquinas (Inglés)Document75 pagesÉtienne Gilson, Wisdom and Love in Saint Thomas Aquinas (Inglés)Anonymous WVuIogNo ratings yet

- The Death of Tolstoy: Russia on the Eve, Astapovo Station, 1910From EverandThe Death of Tolstoy: Russia on the Eve, Astapovo Station, 1910No ratings yet

- Anchorite OrderDocument23 pagesAnchorite OrderJose Jonathan Advincula BitoyNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 - Nature of HumanitiesDocument20 pagesChapter1 - Nature of HumanitiesRad BautistaNo ratings yet

- A Memory for Wonders: A True StoryFrom EverandA Memory for Wonders: A True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Project Gutenberg Ebook, The Merchant of Venice, by William Shakespeare, Edited by Charles KeanDocument85 pagesThe Project Gutenberg Ebook, The Merchant of Venice, by William Shakespeare, Edited by Charles KeanGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Theology of The MassDocument16 pagesTheology of The MassRhyan GomezNo ratings yet

- If You Believed Moses (Vol 2): The Conversion of the Jews as the Close of History: New Old, #5From EverandIf You Believed Moses (Vol 2): The Conversion of the Jews as the Close of History: New Old, #5No ratings yet

- Father Wore Gray ChapterDocument4 pagesFather Wore Gray Chapterapi-270437836No ratings yet

- Willa Cather: Masterpieces: (My Antonia, One of Ours, O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, Alexander's Bridge...) (Bauer Classics)From EverandWilla Cather: Masterpieces: (My Antonia, One of Ours, O Pioneers!, The Song of the Lark, Alexander's Bridge...) (Bauer Classics)No ratings yet

- The Seven Spiritual WeaponsDocument40 pagesThe Seven Spiritual WeaponsClinton LeFortNo ratings yet

- Saint Sharbel From His Contemporaries To Our EraDocument73 pagesSaint Sharbel From His Contemporaries To Our EraPedro Jr BertãoNo ratings yet

- Undo 1492! AproposDocument34 pagesUndo 1492! AproposSaint Benedict CenterNo ratings yet

- Vasil Bykaŭ (Vasil Bykov) : Implementer A. BaranovskayaDocument9 pagesVasil Bykaŭ (Vasil Bykov) : Implementer A. BaranovskayaЕленаNo ratings yet

- Australia's Convict EraDocument10 pagesAustralia's Convict Erafiorela 13No ratings yet

- Carmelite Review Jan-Feb 2002Document16 pagesCarmelite Review Jan-Feb 2002elijahmariaNo ratings yet

- Flannery O'Connor BiographyDocument2 pagesFlannery O'Connor BiographyMelanie100% (1)

- CELTA Pre-interview TaskDocument5 pagesCELTA Pre-interview TaskMehmoud F BokhariNo ratings yet

- Explore The Significance of Crime Element in The Strange Case of DR Jekyll and HydeDocument2 pagesExplore The Significance of Crime Element in The Strange Case of DR Jekyll and HydeQuin IgboayakaNo ratings yet

- Example 1: This Is To Inform You That Your Book Has Been Rejected by Our Publishing Company As It Was Not UpDocument2 pagesExample 1: This Is To Inform You That Your Book Has Been Rejected by Our Publishing Company As It Was Not UpelisabetaNo ratings yet

- Ero's 3.0 Path To Glory Homebrew SupplementDocument11 pagesEro's 3.0 Path To Glory Homebrew Supplementthomas.froh01No ratings yet

- Greek TragedyDocument412 pagesGreek Tragedydespwina100% (5)

- The ModifierDocument1 pageThe ModifierRosalyn AdoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Les's Visit SeattleDocument14 pagesChapter 1 Les's Visit SeattleSage Mode0% (1)

- Darues Dilemma A Marxist Reading of MothDocument15 pagesDarues Dilemma A Marxist Reading of MothSumaira IbrarNo ratings yet

- Grammar SketchDocument15 pagesGrammar SketchMacdie HeyouNo ratings yet

- Syllogism problems and solutionsDocument4 pagesSyllogism problems and solutionsPapan SarkarNo ratings yet

- JaneEyre QuickText PDFDocument31 pagesJaneEyre QuickText PDFBastet Black100% (4)

- Homs EssayDocument4 pagesHoms Essayapi-241530801No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitDocument28 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitThe DLDFNo ratings yet

- Pragmatic Markers in Language UseDocument26 pagesPragmatic Markers in Language UseManuel BujalanceNo ratings yet

- Open Mind Pre Intermediate Teachers Book Unit 9 PDFDocument10 pagesOpen Mind Pre Intermediate Teachers Book Unit 9 PDFIlić Bojana0% (1)

- 5E Manual Del Jugador HDDocument586 pages5E Manual Del Jugador HDRodrigo Jorquera Morales0% (1)

- ISLAMIC MYSTICAL READINGSDocument13 pagesISLAMIC MYSTICAL READINGSRebeccaMastertonNo ratings yet

- Funny CopypastaDocument2 pagesFunny CopypastaJack MartinNo ratings yet

- Gerunds and Infinitives Double ComparativesDocument11 pagesGerunds and Infinitives Double ComparativessubtoNo ratings yet

- An Inspector Calls Revision BookletDocument38 pagesAn Inspector Calls Revision Bookletjasonleefarr50% (2)

- Confusing PronounsDocument1 pageConfusing PronounsdhanuNo ratings yet

- Understanding Plato's RepublicDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Plato's RepublicSharlize AgbayaniNo ratings yet

- Origin of the Freshwater Lake and the Story of Princess PukesDocument3 pagesOrigin of the Freshwater Lake and the Story of Princess PukesAS RizalNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Test 2starDocument2 pagesUnit 3 Test 2starantonio100% (1)

- GW Hardin - Days of WonderDocument226 pagesGW Hardin - Days of WonderKennethZhangNo ratings yet

- Rangkuman Text Bahasa InggrisDocument15 pagesRangkuman Text Bahasa InggrisNovia 'opy' RakhmawatiNo ratings yet

- Akşehir, Mahinur. Duplicity of The City Dr. Jekyll and Mr. HydeDocument17 pagesAkşehir, Mahinur. Duplicity of The City Dr. Jekyll and Mr. HydeFernando Luis BlancoNo ratings yet

- List Anime DVDDocument25 pagesList Anime DVDMalto SeanNo ratings yet

- DE ON TAP - LY THUYET DICH + Đáp ÁnDocument3 pagesDE ON TAP - LY THUYET DICH + Đáp Ándmhiencv100% (2)

- Toeic Academy PDFDocument271 pagesToeic Academy PDFTrang Jqt60% (5)

- Writing Screenplays That Sell: The Complete Guide to Turning Story Concepts into Movie and Television DealsFrom EverandWriting Screenplays That Sell: The Complete Guide to Turning Story Concepts into Movie and Television DealsNo ratings yet

- Surrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSurrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Learn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (136)

- 1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundFrom Everand1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageFrom EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (427)

- How Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideFrom EverandHow Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideNo ratings yet

- Body Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.From EverandBody Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Writing to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllFrom EverandWriting to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (83)

- Learn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Learn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (15)

- The History of English: The Biography of a LanguageFrom EverandThe History of English: The Biography of a LanguageRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Idioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsFrom EverandIdioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)