Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1.4 The Metaphysics and Comprehensive Physics Revealed

1.4 The Metaphysics and Comprehensive Physics Revealed

Uploaded by

Tin-TinPareja0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views2 pagesOriginal Title

4

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views2 pages1.4 The Metaphysics and Comprehensive Physics Revealed

1.4 The Metaphysics and Comprehensive Physics Revealed

Uploaded by

Tin-TinParejaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

1.

4 The metaphysics and comprehensive physics revealed

In a letter of 13 November 1639, Descartes wrote to Mersenne that he was “working on a

discourse in which I try to clarify what I have hitherto written” on metaphysics (2:622). This

was the Meditations, and presumably he was revising or recasting the Latin treatise from

1629. He announced to Mersenne a plan to put the work before “the twenty or thirty most

learned theologians” before it was published. In the end, he and Mersenne collected seven

sets of objections to the Meditations, which Descartes published with the work, along with

his replies (1641, 1642). Some objections were from unnamed theologians, passed on by

Mersenne; one set came from the Dutch priest Johannes Caterus; one set was from the Jesuit

philosopher Pierre Bourdin; others were from Mersenne himself, from the philosophers

Pierre Gassendi and Thomas Hobbes, and from the Catholic philosopher-theologian Antoine

Arnauld.

As previously mentioned, Descartes considered the Meditations to contain the principles of

his physics. But there is no Meditation labeled “principles of physics.” The principles in

question, which are spread through the work, concern the nature of matter (that its essence is

extension), the activity of God in creating and conserving the world, the nature of mind (that

it is an unextended, thinking substance), mind–body union and interaction, and the ontology

of sensory qualities. (Descartes and his followers included topics concerning the nature of

the mind and mind–body interaction within physics or natural philosophy, on which, see

Hatfield 2000.)

Once Descartes had presented his metaphysics, he felt free to proceed with the publication of

his entire physics. However, he needed first to teach it to speak Latin (3:523), the lingua

franca of the seventeenth century. He hatched a scheme to publish a Latin version of his

physics (the Principles) together with a scholastic Aristotelian work on physics, so that the

comparative advantages would be manifest. For this purpose, he chose the Summa

philosophiae of Eustace of St. Paul. That part of his plan never came to fruition. His intent

remained the same: he wished to produce a book that could be adopted in the schools, even

Jesuit schools such as La Flêche (3:233, 523). Ultimately, his physics was taught in the

Netherlands, France, England, and parts of Germany. For the Catholic lands, the teaching of

his philosophy was dampened when his works were placed on the Index of Prohibited Books

in 1663, although his followers in France, such as Jacques Rohault (1618–72) and Pierre

Regis (1632–1707), continued to promote Descartes' natural philosophy.

The Principles appeared in Latin in 1644, with a French translation following in 1647.

Descartes added to the French translation an “Author's Letter” to serve as a preface. In the

letter he explained important elements of his attitude toward philosophy, including the view

that in matters philosophical one must reason through the arguments and evaluate them for

one's self (9B:3). He also presented an image of the relations among the various parts of

philosophy, in the form of a tree:

Thus the whole of philosophy is like a tree. The roots are metaphysics, the trunk is physics,

and the branches emerging from the trunk are all the other sciences, which may be reduced to

three principal ones, namely medicine, mechanics and morals. By “morals” I understand the

highest and most perfect moral system, which presupposes a complete knowledge of the

other sciences and is the ultimate level of wisdom. (9B:14)

The extant Principles offer metaphysics in Part I; the general principles of physics, in the

form of his matter theory and laws of motion, are presented in Part II, as following from the

metaphysics; Part III concerns astronomical phenomena; and Part IV covers the formation of

the earth and seeks to explain the properties of minerals, metals, magnets, fire, and the like,

to which are appended discussions of how the senses operate and a final discussion of

methodological issues in natural philosophy. His intent had been also to explain in depth the

origins of plants and animals, human physiology, mind–body union and interaction, and the

function of the senses. In the end, he had to abandon the discussion of plants and animals

(Princ. IV.188), but he included some discussion of mind–body union in his abbreviated

account of the senses.

You might also like

- 5 Philosophers That Are Also Mathematicians: Pythagoras, (Born C. 570 BCE, Samos, Ionia (Greece) - Died C. 500Document3 pages5 Philosophers That Are Also Mathematicians: Pythagoras, (Born C. 570 BCE, Samos, Ionia (Greece) - Died C. 500Shaimer Cinto100% (2)

- Powers and Properties of Numbers in Rosicrucian MetaphysicsDocument9 pagesPowers and Properties of Numbers in Rosicrucian MetaphysicsSteven MarkhamNo ratings yet

- Canadian Daily Reading Comprehension Grade 3 (George Murray) (Z-Library)Document125 pagesCanadian Daily Reading Comprehension Grade 3 (George Murray) (Z-Library)Yi Chi Wang100% (1)

- Resume and Cover Letter 18 Accessible2019 PDFDocument17 pagesResume and Cover Letter 18 Accessible2019 PDFJaegerNo ratings yet

- Graduate TranscriptDocument12 pagesGraduate Transcriptapi-255841753No ratings yet

- Meditations on First Philosophy/ Meditationes de prima philosophia: A Bilingual EditionFrom EverandMeditations on First Philosophy/ Meditationes de prima philosophia: A Bilingual EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (381)

- Discourse on Method and Meditations of First Philosophy (Translated by Elizabeth S. Haldane with an Introduction by A. D. Lindsay)From EverandDiscourse on Method and Meditations of First Philosophy (Translated by Elizabeth S. Haldane with an Introduction by A. D. Lindsay)No ratings yet

- AristotleDocument126 pagesAristotlenda_naumNo ratings yet

- Descartes' Metaphysical PhysicsDocument394 pagesDescartes' Metaphysical PhysicsEspaço Filosofia100% (1)

- Ernst Marti - The Four EthersDocument33 pagesErnst Marti - The Four Ethersg100% (2)

- Philip Merlan, From Platonism To NeoplatonismDocument267 pagesPhilip Merlan, From Platonism To NeoplatonismAnonymous fgaljTd100% (1)

- Descartes' System of Natural PhilosophyDocument267 pagesDescartes' System of Natural PhilosophyEspaço Filosofia100% (1)

- Johannes KeplerDocument25 pagesJohannes KeplersigitNo ratings yet

- English On The Go 2 Teachers PDFDocument124 pagesEnglish On The Go 2 Teachers PDFLi Izz100% (1)

- Descartes' Physics: 1. A Brief History of Descartes' Scientific WorkDocument21 pagesDescartes' Physics: 1. A Brief History of Descartes' Scientific WorksonirocksNo ratings yet

- René DescartesDocument41 pagesRené DescartesJoseph Arian Regalado DazaNo ratings yet

- Meditations and Other Metaphysical Writings by René DescartesDocument13 pagesMeditations and Other Metaphysical Writings by René DescartesMika Scholes0% (2)

- 1.5 Theological Controversy, Passions, and Death: 2. Philosophical DevelopmentDocument3 pages1.5 Theological Controversy, Passions, and Death: 2. Philosophical DevelopmentTin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- Explanation: 2. A. B. 3. 4. - A. 5. - A. 6.Document8 pagesExplanation: 2. A. B. 3. 4. - A. 5. - A. 6.monmonNo ratings yet

- René Descartes: First Published Wed Dec 3, 2008 Substantive Revision Thu Jan 16, 2014Document4 pagesRené Descartes: First Published Wed Dec 3, 2008 Substantive Revision Thu Jan 16, 2014Tin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy-Term-Paper - ArselDocument15 pagesPhilosophy-Term-Paper - ArselShaira MejaresNo ratings yet

- Biography of René Descartes: Nash L. Acosta 9-St. ThereseDocument4 pagesBiography of René Descartes: Nash L. Acosta 9-St. ThereseIan AcostaNo ratings yet

- Zeno of Elea: Philosophic Naturalism Principia Mathematical (Usually Called The Principia) Is Considered ToDocument4 pagesZeno of Elea: Philosophic Naturalism Principia Mathematical (Usually Called The Principia) Is Considered ToVijay PeriyasamyNo ratings yet

- Rene Descartes1Document19 pagesRene Descartes1Ilya Naila NazaviaNo ratings yet

- PHILOSOPHICALDocument4 pagesPHILOSOPHICALBlessie Vhine MostolesNo ratings yet

- Early Life: Meditations Defined The Basic Problems of Philosophy For at Least A CenturyDocument4 pagesEarly Life: Meditations Defined The Basic Problems of Philosophy For at Least A Centuryjanina mykaNo ratings yet

- Revolutions of The Heavenly Spheres in 1543, The Same YearDocument4 pagesRevolutions of The Heavenly Spheres in 1543, The Same YearAsh HassanNo ratings yet

- Rene BioDocument63 pagesRene BioGlenn PapaNo ratings yet

- SpinozaDocument18 pagesSpinozaReza KhajeNo ratings yet

- The Scientific Revolution at Its Zenith 1620 1720Document13 pagesThe Scientific Revolution at Its Zenith 1620 1720illumin24No ratings yet

- Biography: Meditations On First PhilosophyDocument9 pagesBiography: Meditations On First PhilosophyNur AmanahNo ratings yet

- Meister Eckhart (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document14 pagesMeister Eckhart (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)sandroNo ratings yet

- Indoiala CartezianaDocument12 pagesIndoiala CartezianaCornelia TarNo ratings yet

- Cosmographia (Also Known As de Mundi Universitate) Is A: ProsimetrumDocument5 pagesCosmographia (Also Known As de Mundi Universitate) Is A: ProsimetrumjorgefilipetlNo ratings yet

- 17th CenturyDocument2 pages17th CenturyMika Angea AbuemeNo ratings yet

- Rene DescartesDocument10 pagesRene DescartesPunitha gbNo ratings yet

- Descartes Locke 1 PDFDocument36 pagesDescartes Locke 1 PDFRenefe RoseNo ratings yet

- Dekart, Spinoza, Nice I OstaliDocument104 pagesDekart, Spinoza, Nice I OstaliPredrag KovacicNo ratings yet

- The Correspondence Theory of TruthDocument4 pagesThe Correspondence Theory of TruthJouie CailasNo ratings yet

- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: Charles DarwinDocument4 pagesPierre Teilhard de Chardin: Charles DarwinMimi QueyquepNo ratings yet

- Science Atomic TheoryDocument8 pagesScience Atomic TheoryMary Jasmine AzulNo ratings yet

- Albert The Great S Early Conflations ofDocument20 pagesAlbert The Great S Early Conflations oftinman2009No ratings yet

- AristotleDocument3 pagesAristotleAmhyr De Mesa DimapilisNo ratings yet

- William of OckhamDocument4 pagesWilliam of OckhamdmpmppNo ratings yet

- Invisible Wombs Rethinking Paracelsus S Concept of Body and MatterDocument15 pagesInvisible Wombs Rethinking Paracelsus S Concept of Body and MatterMateas TaviNo ratings yet

- Aristotle and Oxford PhilosophyDocument10 pagesAristotle and Oxford PhilosophyJaime UtrerasNo ratings yet

- Andrew Janiak - Newton and Descartes - Theology and Natural PhilosophyDocument22 pagesAndrew Janiak - Newton and Descartes - Theology and Natural Philosophyrebe53100% (1)

- Intro To Philo Card Game CharactersDocument10 pagesIntro To Philo Card Game CharactersZiaNo ratings yet

- The History of LinguisticsDocument10 pagesThe History of LinguisticsAyunanda PutriNo ratings yet

- The Basic Ideas in The Philosophy of Law of St. Thomas Aquinas As Found in The "Summa Theologica"Document20 pagesThe Basic Ideas in The Philosophy of Law of St. Thomas Aquinas As Found in The "Summa Theologica"Daniel CiobanuNo ratings yet

- Rene Descartes A Renowned French Mathematician in The 16th CenturyDocument4 pagesRene Descartes A Renowned French Mathematician in The 16th CenturyTing Sing HoNo ratings yet

- Taylor, Avicenna and Aquinas's de Principiis NaturaeDocument34 pagesTaylor, Avicenna and Aquinas's de Principiis NaturaePredrag MilidragNo ratings yet

- René Descartes Biography: Quick FactsDocument13 pagesRené Descartes Biography: Quick FactsAngela MiguelNo ratings yet

- Clatterbaugh Causality in Modern British Philosophy 2002Document11 pagesClatterbaugh Causality in Modern British Philosophy 2002Federico OrsiniNo ratings yet

- Rene Descartes EngDocument2 pagesRene Descartes Engzaknjige122No ratings yet

- The Basic Ideas in The Philosophy of Law of St. Thomas Aquinas AsDocument20 pagesThe Basic Ideas in The Philosophy of Law of St. Thomas Aquinas AsArvhie SantosNo ratings yet

- DescartesDocument24 pagesDescartesAlex TusaNo ratings yet

- Biography: French PronunciationDocument9 pagesBiography: French Pronunciationbudakbaru33No ratings yet

- History of Science PhilosophyDocument21 pagesHistory of Science PhilosophyJune HerreraNo ratings yet

- MacLennan NIS Revision2Document22 pagesMacLennan NIS Revision2BJMacLennanNo ratings yet

- Moorman, R. - The Influence of Mathematics On The Philosophy of SpinozaDocument9 pagesMoorman, R. - The Influence of Mathematics On The Philosophy of SpinozadiotrephesNo ratings yet

- Neoplatonism in Science: Past and Future (Extended Version)Document17 pagesNeoplatonism in Science: Past and Future (Extended Version)BJMacLennanNo ratings yet

- René DescartesDocument3 pagesRené DescartesTon JanabanNo ratings yet

- Nature Speaks: Medieval Literature and Aristotelian PhilosophyFrom EverandNature Speaks: Medieval Literature and Aristotelian PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- 1.2 First Results, A New Mission, and MethodDocument2 pages1.2 First Results, A New Mission, and MethodTin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- Organic ContentDocument4 pagesOrganic ContentTin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Biography: 1.1 Early Life and EducationDocument2 pagesIntellectual Biography: 1.1 Early Life and EducationTin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- René Descartes: First Published Wed Dec 3, 2008 Substantive Revision Thu Jan 16, 2014Document4 pagesRené Descartes: First Published Wed Dec 3, 2008 Substantive Revision Thu Jan 16, 2014Tin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- 1.5 Theological Controversy, Passions, and Death: 2. Philosophical DevelopmentDocument3 pages1.5 Theological Controversy, Passions, and Death: 2. Philosophical DevelopmentTin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology, and Society: Ceding Debate: Biotechnology and AgricultureDocument3 pagesScience, Technology, and Society: Ceding Debate: Biotechnology and AgricultureTin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology, and Society: The Need For Radical Overhaul of Science EducationDocument4 pagesScience, Technology, and Society: The Need For Radical Overhaul of Science EducationTin-TinParejaNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument53 pagesChapter IMerly RamosNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On GymDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Gymrtggklrif100% (1)

- Excoriation (Skin-Picking) Disorder: A Systematic Review of Treatment OptionsDocument6 pagesExcoriation (Skin-Picking) Disorder: A Systematic Review of Treatment OptionsBecados PsiquiatriaNo ratings yet

- Meaningful Commitment - Finding Meaning in Volunteer WorkDocument20 pagesMeaningful Commitment - Finding Meaning in Volunteer WorkSantiago LopezNo ratings yet

- Module III Microsoft ExcelDocument17 pagesModule III Microsoft ExcelSoumya RoyNo ratings yet

- Courses of Study For PG Programmes - 2019-21 PDFDocument484 pagesCourses of Study For PG Programmes - 2019-21 PDFBaka NuduNo ratings yet

- Music-7-Week-4 LASDocument5 pagesMusic-7-Week-4 LASRube John OrbetaNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal Brigada PagbasaDocument4 pagesProject Proposal Brigada PagbasaCATHYRINE AUDIJE-RADAMNo ratings yet

- Alternative System-Building ApproachesDocument14 pagesAlternative System-Building ApproachesArun MishraNo ratings yet

- Reading Street Unit 1Document5 pagesReading Street Unit 1Cindy Meyer HulseyNo ratings yet

- Cover LetterDocument2 pagesCover Letterapi-242812851No ratings yet

- Senate SimulationDocument3 pagesSenate Simulationapi-307857011No ratings yet

- Study Habits of Nigerian University StudentsDocument7 pagesStudy Habits of Nigerian University StudentsPaulene Marie SicatNo ratings yet

- GC2 Examiners' Reports Aug - Oct 2014Document11 pagesGC2 Examiners' Reports Aug - Oct 2014Faisal AhmedNo ratings yet

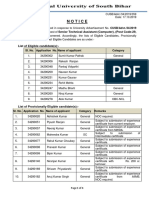

- Notice: Senior Technical Assistant (Computer), (Post Code-29, Post-UR-1)Document4 pagesNotice: Senior Technical Assistant (Computer), (Post Code-29, Post-UR-1)Dhananjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Evidence Describing Outfits and LikesDocument8 pagesEvidence Describing Outfits and LikesDiiegoRojasHernandezNo ratings yet

- Leveling Workshop. A1: Unit 5Document4 pagesLeveling Workshop. A1: Unit 5Ines Eugenia CaldasNo ratings yet

- Thesis For Architecture Graduation ProjectDocument7 pagesThesis For Architecture Graduation Projectpzblktgld100% (1)

- 1st Lecture - Philosophy 101Document14 pages1st Lecture - Philosophy 101fdgh safdghfNo ratings yet

- Apa 6 Bgs Quantitative Research Paper 03 2015Document50 pagesApa 6 Bgs Quantitative Research Paper 03 2015Jakie UbinaNo ratings yet

- Summative Test:: Research in Daily Life IIDocument2 pagesSummative Test:: Research in Daily Life IIMaria Shiela Cantonjos Maglente0% (1)

- Problem Solving Skills in LawDocument9 pagesProblem Solving Skills in LawupendraNo ratings yet

- Responding To Negative Internal ExperienDocument9 pagesResponding To Negative Internal ExperienJoseAcostaDiazNo ratings yet

- MMW Research PaperDocument11 pagesMMW Research PaperJaica Ann RicaldeNo ratings yet

- Microsoft EncartaDocument8 pagesMicrosoft EncartaAris MabangloNo ratings yet

- Ici Jan (R) 2022 - Final Project BriefDocument6 pagesIci Jan (R) 2022 - Final Project Brief2023140639No ratings yet