Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ethical Impotence

Uploaded by

MehinCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ethical Impotence

Uploaded by

MehinCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of College and Character

ISSN: 2194-587X (Print) 1940-1639 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujcc20

Ethical Impotence

Robert J. Sternberg

To cite this article: Robert J. Sternberg (2015) Ethical Impotence, Journal of College and

Character, 16:3, 180-185, DOI: 10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154

Published online: 19 Aug 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 191

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 1 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujcc20

Download by: [ADA University] Date: 23 August 2016, At: 05:52

180 Opinions and Perspectives

Journal of College & Character VOLUME 16, No. 3, August 2015

Ethical Impotence

1

Robert J. Sternberg, Cornell University

Abstract

Ethical impotence occurs when one wants to act ethically but feels powerless to do anything about

the perceived unethical behavior. One may feel that one’s actions will have no impact or that those

actions actually will have harmful consequences to oneself and/or others. Ethical impotence can be

understood in terms of an eight-step model of ethical reasoning. It is important that students learn to

act ethically, even when they fear their actions will come to naught or be potentially challenging in

their consequences.

When I was a dean, a faculty member came to complain to me about unethical behavior he had observed in his

department that had upset him deeply. I agreed that the behavior he described appeared to be unethical. There

was just one problem: The faculty member’s department was in another school of the university. When I

suggested to him that he go to see his own dean, he responded that he would not do so because he knew with

certainty that the dean would not respond to the charge. Rather, the dean would get upset with him for

reporting the behavior. I did not know at the time whether indeed his dean would respond as he believed, but I

knew that he was experiencing something many of us experience at one time or another—ethical impotence,

or the belief that if we act ethically, it will have no meaningful effect, other than perhaps to get us into trouble.

The sense of ethical impotence that faculty members sometimes feel may also be experienced by staff

and students, the latter being particularly vulnerable. Students often feel powerless against other students,

professors, or institutions that they may feel have acted unethically because others have far more stature

and authority than the students perceive themselves to have.

What do the less powerful do in the face of ethical conundrums when they feel themselves to be

ethically impotent—unable to act in any meaningful way that would change a situation that is ethically

compromised? How can they respond when they are ethically compelled to act and yet expect only trouble

as a result of their actions?

Sternberg (2010) offered an eight-step model of ethical reasoning that can be very helpful in such

situations. Some people believe that to act ethically is easy and to act unethically requires extra steps in

one’s thought processes as one contemplates violations of ethical rules. This model argues, in contrast, that

ethical behavior often is not easy but rather is hard to execute precisely because it involves so many steps.

1

Robert J. Sternberg (robert.sternberg@cornell.edu) is professor of human development at Cornell University. He is a past-

president of the American Psychological Association, the Eastern Psychological Association, and the Federation of Associations

in Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

doi:10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154 http://journals.naspa.org/jcc © NASPA 2015 JCC

Ethical Impotence 181

The model, as currently formulated, describes those steps as follows: (a) recognizing that a situation

exists to which a response may be needed, (b) defining the situation as having an ethical dimension, (c)

viewing the ethical dimension of the situation as serious enough to be worthy of one’s attention, (d)

deciding that one has a personal ethical responsibility in the matter, (e) deciding what ethical principle or

principles apply, (f) deciding how to apply that principle or those principles in the current situation, (g)

preparing for possible negative consequences if one acts, and (h) acting.

Step 5 can be a particular challenge because people interpret ethical challenges so differently. They

may even have different ideas as to what constitutes an ethical principle. For example, “Do not kill” may be

accepted, but the question arises as to “do not kill” whom? However, it is the seventh step in Sternberg’s

(2010) model when one may experience ethical impotence—a sense that nothing good is likely to come of

one’s acting in an ethical way but that plenty of bad consequences await one. Ethical impotence can have

many sources in a university environment: reporting on an impropriety in athletics in a university that will

hear no evil with respect to its athletic program; blowing the whistle on a professor who one knows is

closely connected to, and perhaps even married to, a superior who would be involved in adjudicating the

problematic situation; reporting an impropriety on the part of one’s academic advisor when there is no one

else in one’s department who would be willing or able to serve as one’s advisor; peer pressure mitigating

against reporting an act of academic misconduct by fellow students; or simply sensing that the culture of

the university is to cover up rather than bring to the light of day ethical transgressions.

The question then becomes: What does one do after having observed an ethical transgression in the

face of no clear action or set of actions that one judges is at least reasonably likely to lead to a correction of

an unethical situation? How should we, as faculty and administrators, teach students to respond to such

fraught situations? At some time or another, almost all of us will face such a situation in our careers. What

do we do about it? What would we tell our students to do about it?

There are four major options—say nothing, and do nothing; say something, and do nothing; say

nothing, and do something; and say something, and do something. Consider each of these in turn.

Say Nothing; Do Nothing

The advantage of saying and doing nothing is that nothing the individual does makes a bad situation worse.

One acknowledges one’s ethical impotence and moves on to other things in one’s life. The problem with the

“say nothing; do nothing” approach is that ethical problems left alone often become worse. And do we want to

teach the next generation to “hear no evil; see no evil” in response to compromised ethical situations?

In my experience as an administrator, I became aware very late of a sexual harasser who, for many

years, got away with being a harasser. The students who were harassed were afraid to act because of the

harasser’s power both in his field and in his university. They felt impotent in the face of his harassment.

Eventually, however, one of his victims fought back, leading to appropriate sanctions against the professor

and, for better or worse, negative attention in the media for the professor and the university. Obviously, I

would have hoped to be able to say now that all’s well that ends well, but the student who filed the charges

dropped out of her graduate program, despite encouragement to find another advisor.

This sequence of events highlights an aspect of the model of ethical reasoning in the eight-step

model: Whistle-blowing sometimes, perhaps often, has adverse consequences for the whistle-blower. In this

case, it was not that the student was forced out. She just had had enough. Her doing the right thing brought

her no real personal gain—on the contrary, she left school.

JCC © NASPA 2015 http://journals.naspa.org/jcc doi:10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154

182 Journal of College & Character VOLUME 16, No. 3, August 2015

The lives of whistle blowers are not always affected in such a manner. In another instance, members

of the laboratory of a well-known scientist reported that the scientist was fabricating data (Bhattacharjee,

2013). The scientist originally tried to make the students feel impotent by retaliating against the students,

but in the end, it was the scientist whose career was cooked, and the lab members did just fine and, indeed,

became heroes for having the courage to act against such a powerful individual.

On a larger scale, genocides such as in Rwanda and Nazi Germany illustrate the problem of the say

nothing; do nothing approach. As long as no one talked about what was happening, despite many people

knowing about it, the genocides continued. Had Nazi Germany not invaded other countries in Europe, for

example, it is not altogether clear whether other countries would have acted to stop the atrocities of Hitler

and his ministers.

Say Something; Do Nothing

The advantage of this approach is that, at the very least, one expresses one’s moral outrage. If one cannot

do anything to stop what is happening, at least one makes a statement against it. The problem with this

approach is that, although a picture may be worth a thousand words, in the case of ethical misconduct, an

action may be worth far more than a thousand words. There is no time that words ring more hollow than

when they are belied by inaction.

As an administrator, I became involved with the issue of whether cases of student plagiarism should

necessarily be reported to the administration of the school for which I was an administrator. Formerly,

professors had the option either of reporting or not reporting such cases to the school administration. The

problem that arose was that administrators were enforcing university policies on plagiarism in an uneven

way. In their view, probably, they were using their good judgment. But in some cases, it became clear that

the faculty members just did not want to become involved in what could be a time-consuming and

distressing judicial proceeding against a student, which, in the end, might lead to no action being taken

against the student but to their being sued. In this case, the student, whose parents might be able to hire a

powerful (and high-priced) lawyer, might have more power than they. As a result, some students were

simply verbally admonished not to plagiarize again, and predictably, many of them did indeed go on to do

it again. Because there were no college records of the cases, other professors typically had no idea that the

students had a past record of plagiarizing. So the students got away with it again and again.

My experience was that faculty members needed to act against, not just speak with the students to

change the students’ behavior—and that the faculty members, in the long run, were doing the students a

favor by taking such action. But their actions often did leave them with the extra work and personal

confrontations they dreaded.

On a larger scale, the limits of verbal outrage are shown by the current situation in Syria. There has

been a great deal of talk on the part of various world leaders, including our own, about stopping the

slaughter, but little action taken. The result has been that the slaughter continues and world leaders continue

to talk about it. It is not clear what action would have led to a positive outcome, but words accompanied by

inaction have been notably lacking in success in saving lives.

Say Nothing; Do Something

The advantage of this approach is that it enables one to act against unethical behavior in what one believes

is an appropriate way without necessarily identifying that it is indeed oneself who is the counter-actor.

doi:10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154 http://journals.naspa.org/jcc © NASPA 2015 JCC

Ethical Impotence 183

Anonymous whistle-blowers and also governments that act against perceived saboteurs without publicly

announcing their intentions or actions take this approach. State-sponsored intelligence agencies often act in

this way, retaliating against enemies (and perceived enemies) without admitting that they are involved in

the situation in any way.

The disadvantage of this approach is that it creates a great deal of ethical ambiguity. For example, it

sometimes results in an agent retaliating against someone who was perceived to be guilty of an offense but

actually was not guilty. Because there was no public judicial proceeding of any kind against the individual,

there never was any confirmation that the individual was responsible for the perceived ethical outrage.

Moreover, when the results of the retaliation become public, it is not clear who did the retaliation, and

sometimes agents of dubious ethical provenance themselves claim the credit, when in fact they were

uninvolved.

During my time in administration, a private university one day announced that its president was

gone (McGuinness, 2012). The board announced that soon there would be an interim president in

place, but meanwhile, the provost was taking over on an interim basis. It was pretty obviously a firing

because the now ex-president spoke out that he should have been allowed to keep his job. But what

had he done? Publicly, there was no clue. The rumor was that he had privately done something

seriously unethical that had disgraced him and the university. But was it true? And if so, what

was “it”?

I heard several different rumors about what “it” was but never heard any confirmation of any

of them. The problem with the board’s course of action was that the opportunity for a lesson to

others was lost. Others could not learn to avoid such unethical action because they never learned

what the unethical action was, if indeed there was one. In repressive dictatorships, governments

actually use unexplained disappearances to inspire fear: If a person transgresses, one never knows

when he or she will disappear or exactly for what cause. Of course, this scenario was not the intention

of the board of trustees. But their handling of what presumably was a major ethical lapse left others

unclear as to what they could learn from the situation. If there was a teaching opportunity, the board

did not take it.

Say Something; Do Something

In an ideal world, “say something; do something” would be the response of choice in ethically challenging

situations. The problem is that in situations of ethical impotence, it often is not at all clear what one can or

should do. In many situations, universities or parts of them try to act even when they are ethically impotent.

The problem is that in the face of large ethical problems, they are not always effective. However they may

perceive themselves, academics are no better at dealing with their own ethical impotence than is anyone

else. Their IQs do not seem to give them any special insights into how to act in the face of ethical

impotence, and there is no reason they should. For example, selective boycotts imposed by academics

sometimes have an air of capriciousness about them, leaving those uninvolved wondering why the

particular targets were chosen, how the boycotts would be in any way effective, and whether the boycotts

actually teach students the lessons professors should want to teach them.

There are several reasons, though, that wisely chosen action may be the preferred option over doing

nothing. Consider these reasons as illustrated by the case of a student considering whether to go to a

department chair or dean to accuse a senior faculty member of academic misconduct. All students need to

JCC © NASPA 2015 http://journals.naspa.org/jcc doi:10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154

184 Journal of College & Character VOLUME 16, No. 3, August 2015

know the reasons for a wisely chosen action as they confront ethically challenging situations in which they

feel ethically impotent in some degree.

1. Doing nothing makes a statement about one’s ethical stance. If the individual does nothing, it makes

a statement about the individual’s ethical stance as well as the individual’s character in much the same

way that allowing unethical behavior in business or in national politics makes a statement about the

current state of each of those enterprises. To do nothing is to say that one does not care about ethical

misconduct, or that one lacks the courage to do anything about such misconduct, or even that one

views the conduct as acceptable. The lesson the individual may be learning is that it is all right to

allow ethical misconduct if one feels powerless to confront it.

2. Even if action is unsuccessful, it at least makes a symbolic statement. Sometimes, when one acts

against ethical misconduct, the result is less or even much less than one ideally would have hoped for.

But one nevertheless has made a symbolic statement. And a series of those symbolic statements, as

made by courageous people around the world, have brought down unethical individuals and

governments alike.

3. One at least can live at peace with oneself. When one permits ethical misconduct to go unchallenged,

the experience stays with one for one’s entire life. One knows that when he or she could have and

indeed should have acted, he or she instead chose to remain silent.

4. One may prevent others from harm. Not only does one need to live with one’s lack of action, but

unfortunately, other individuals may have to live with it as well when they later become subject to the

misconduct of the same malefactor. Serial transgressors often continue to commit unethical acts

because no one made any attempt to stop them.

5. Sometimes one is not as impotent as one thinks. The perception of ethical impotence can become an

excuse to do nothing. One ascribes powerlessness to oneself as a cop out, perhaps without even

testing the limits of one’s power. If nonviolent “flower power” movements could bring down whole

governments in Eastern Europe, and if people like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King could

change whole societies through nonviolence, why is one so confident that he or she is utterly lacking

in power to effect change?

6. Change has to start somewhere. If one does not act, and no else does either, nothing is likely to

change. We all have the power at least to start a process of change, even if the process proves to be a

long and perhaps seemingly endless one.

Students and professionals alike need to learn to deal with feelings of ethical impotence—to speak

and act despite one’s feelings of powerlessness. At some time in our lives, we all have such feelings. The

question is not whether we will have them but whether we will think, speak, and act to do what we believe

is right. To speak and act wisely, even in the face of feelings of ethical impotence, is a decision any of us

can make. And it is a decision-making process we need to convey to our students if indeed our students are

ever to create a better world for future generations. There are many situations in which people feel ethically

impotent. But if students do not learn to act ethically despite their feelings of impotence, what hope is there

for the next generation?

doi:10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154 http://journals.naspa.org/jcc © NASPA 2015 JCC

Ethical Impotence 185

References

Bhattacharjee, Y. (2013, April 26). The mind of a con man. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/

04/28/magazine/diederik-stapels-audacious-academic-fraud.html?pagewanted=all

McGuinness, W. (2012, Sept. 13). Geoffrey Orsak, University of Tulsa President, fired after only 74 days in office.

Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/09/13/geoffrey-orsak-university_n_1881196.

html

Sternberg, R. J. (2010). Teaching for ethical reasoning in liberal education. Liberal Education, 96(3), 32–37.

JCC © NASPA 2015 http://journals.naspa.org/jcc doi:10.1080/2194587X.2015.1057154

You might also like

- Bad Behavior (Non-Punctuality)Document23 pagesBad Behavior (Non-Punctuality)Ali ZulfiqarNo ratings yet

- RavanaDocument8 pagesRavanaArjun UpendraNo ratings yet

- Advantage Solutions - U.S. Associate Handbook Final 2020 DL v.2Document47 pagesAdvantage Solutions - U.S. Associate Handbook Final 2020 DL v.2Marcy Henich LucchesiNo ratings yet

- Learning Assessment 2Document4 pagesLearning Assessment 2darylNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument63 pagesPDFjackfred99No ratings yet

- DeedDocument2 pagesDeedDIA design innovations80% (5)

- Ethics For Behavior Analysts 3rd Edition Ebook PDFDocument41 pagesEthics For Behavior Analysts 3rd Edition Ebook PDFsarah.kowalchuk906100% (35)

- Alcantara-Pica V Carigo Art 559Document7 pagesAlcantara-Pica V Carigo Art 559Angel EiliseNo ratings yet

- CIAP-PCAB Citizen's Charter - Procedures For Filing of Complaint - Complaints Vs Unlicensed - 26sep2016Document3 pagesCIAP-PCAB Citizen's Charter - Procedures For Filing of Complaint - Complaints Vs Unlicensed - 26sep2016fortunec100% (1)

- CoC - Japanese ListsDocument6 pagesCoC - Japanese ListsAres Santiago R. NoguedaNo ratings yet

- Oath of SportsmanshipDocument1 pageOath of SportsmanshipZhenrry Laqui Ustare89% (9)

- Pimentel v. Joint CommitteeDocument2 pagesPimentel v. Joint CommitteeCZARINA ANN CASTRO100% (2)

- Bago Economic CrimesDocument50 pagesBago Economic CrimesRAYMON ROLIN HILADONo ratings yet

- 5 - GONZALES v. ABAYADocument3 pages5 - GONZALES v. ABAYAmark anthony mansuetoNo ratings yet

- Directory of Officers and EmployeesDocument25 pagesDirectory of Officers and EmployeesHari ReddyNo ratings yet

- Sociology Senior Thesis IdeasDocument4 pagesSociology Senior Thesis Ideasmarcygilmannorman100% (2)

- 02 Bocchiaro Et Al 2012 To Defy or Not To DefyDocument17 pages02 Bocchiaro Et Al 2012 To Defy or Not To DefyFrancis Gladstone-QuintupletNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Qualitative ResearchDocument17 pagesEthical Issues in Qualitative Researchniki098No ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in ThesisDocument5 pagesEthical Issues in Thesisalyssadennischarleston100% (1)

- Tinto's Model of Student RetentionDocument19 pagesTinto's Model of Student RetentionraviNo ratings yet

- 2module 8 Stages of Moral DevelopmentDocument6 pages2module 8 Stages of Moral DevelopmentAnna Liza PaquitNo ratings yet

- Tutorías Ingles IVDocument15 pagesTutorías Ingles IVmayteNo ratings yet

- List of Thesis Topics in Social WorkDocument4 pagesList of Thesis Topics in Social Workmcpvhiief100% (2)

- Ethics Module 1 Lesson 1Document4 pagesEthics Module 1 Lesson 1Fe RequinoNo ratings yet

- Essay On PhotographerDocument7 pagesEssay On Photographerfllahvwhd100% (2)

- Introduction To Sociology Ethics Decisions ExerciseDocument1 pageIntroduction To Sociology Ethics Decisions ExerciseFrancis Xavier Robles SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Moral Hypocrisy and Acting For Reasons: How Moralizing Can Invite Self-DeceptionDocument13 pagesMoral Hypocrisy and Acting For Reasons: How Moralizing Can Invite Self-DeceptionmikadikaNo ratings yet

- List Thesis Topics SociologyDocument6 pagesList Thesis Topics Sociologyfipriwgig100% (2)

- Fem CourseworkDocument6 pagesFem Courseworkf5dbf38y100% (2)

- Assignment No.1 Pa16Document3 pagesAssignment No.1 Pa16Clare GonzagaNo ratings yet

- FA 2 Reflexive PaperDocument3 pagesFA 2 Reflexive PaperTaniyaNo ratings yet

- Social Psychology Research PapersDocument7 pagesSocial Psychology Research Papersihprzlbkf100% (1)

- Bullying Sample ThesisDocument9 pagesBullying Sample Thesisandrealeehartford100% (2)

- Ou Honors ThesisDocument6 pagesOu Honors Thesisotmxmjhld100% (2)

- Ideas For A Research Paper On BullyingDocument4 pagesIdeas For A Research Paper On Bullyingfys374dr100% (3)

- Research Paper About Bullying in High SchoolDocument6 pagesResearch Paper About Bullying in High Schooljiyzzxplg100% (1)

- In Defense of IndividualismDocument7 pagesIn Defense of IndividualismRayGerasNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Peer PressureDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Peer Pressuregw0drhkf100% (1)

- Introduction in Research Paper About BullyingDocument7 pagesIntroduction in Research Paper About Bullyingnidokyjynuv2100% (1)

- Similarities: External Rules May Vary Between Environments Personal Principles Rarely ChangeDocument26 pagesSimilarities: External Rules May Vary Between Environments Personal Principles Rarely ChangeAnthonatte Castillo SambalodNo ratings yet

- Term Paper SociologyDocument8 pagesTerm Paper Sociologyaflsswofo100% (1)

- Short Thesis Statement About BullyingDocument7 pagesShort Thesis Statement About Bullyingshannonwilliamsdesmoines100% (2)

- Social Psychology Possible Thesis TopicsDocument5 pagesSocial Psychology Possible Thesis TopicsBuyEssaysCheapErie100% (2)

- Ethics MidtermsDocument16 pagesEthics MidtermsLOUISSE ANNE MONIQUE L. CAYLONo ratings yet

- Bullying Research Paper Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesBullying Research Paper Thesis StatementPayPeopleToWritePapersCanada100% (2)

- Literature Review On BullyingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Bullyingaflsbegdo100% (1)

- Disorientation Guide 2009Document18 pagesDisorientation Guide 2009CorporateCampusUoGNo ratings yet

- Value of Life Thesis StatementDocument6 pagesValue of Life Thesis Statementbsgyhhnc100% (2)

- Research Paper On Human BehaviorDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Human Behavioregya6qzc100% (1)

- Research Paper Topics For BullyingDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Topics For Bullyingfzjzn694100% (1)

- Research Paper About Bullying LawsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper About Bullying Lawstrsrpyznd100% (1)

- Happenstance Learning TheoryDocument21 pagesHappenstance Learning TheorycornelpcNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in Sociological ResearchDocument34 pagesEthical Considerations in Sociological ResearchFahim Ashab ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- 1 Common Ethical TheoriesDocument37 pages1 Common Ethical TheoriesRose Bella Tabora LacanilaoNo ratings yet

- Dependency Thesis EthicsDocument5 pagesDependency Thesis Ethicslorieharrishuntsville100% (1)

- Second Life Research PaperDocument7 pagesSecond Life Research Paperxilllqwhf100% (1)

- Disciplines and Ideas of Social SciencesDocument5 pagesDisciplines and Ideas of Social SciencesAlthea DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Research Discrimination ResuméDocument11 pagesResearch Discrimination ResuméColling WoodNo ratings yet

- Ontology of PlagiarismDocument3 pagesOntology of PlagiarismAnaIordNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Bullying AbstractDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About Bullying Abstractscongnvhf100% (1)

- Thesis Career ChoiceDocument8 pagesThesis Career ChoiceSabrina Baloi100% (2)

- Ethics ReportDocument2 pagesEthics ReportHans SabordoNo ratings yet

- Peer Pressure Research Paper OutlineDocument7 pagesPeer Pressure Research Paper Outlinefvdddmxt100% (1)

- (Flash.) Thompson, Mel - Ethics Made Easy - Flash-Hodder Education (2011)Document98 pages(Flash.) Thompson, Mel - Ethics Made Easy - Flash-Hodder Education (2011)Arago, Kathrina Julien S.No ratings yet

- What Is An Ethical DilemmaDocument6 pagesWhat Is An Ethical DilemmaRana Samee KhalidNo ratings yet

- Sample Research Paper Social WorkDocument7 pagesSample Research Paper Social Worklrqylwznd100% (1)

- Interesting Sociology Dissertation TopicsDocument4 pagesInteresting Sociology Dissertation TopicsCheapPaperWritingServicesOmaha100% (1)

- Sociology Term Paper ExampleDocument8 pagesSociology Term Paper Exampleaflsktofz100% (1)

- Thesis Ethics PaperDocument7 pagesThesis Ethics Paperlaurenbrownprovo100% (2)

- ETHICS 1.2 READING MATERIALdocxDocument4 pagesETHICS 1.2 READING MATERIALdocxJohnny King ReyesNo ratings yet

- Biology Reflection - EditedDocument5 pagesBiology Reflection - Editedcharobetty80No ratings yet

- CCTV Implementing By-Law and DecisionsDocument12 pagesCCTV Implementing By-Law and DecisionssultanprinceNo ratings yet

- AMIND 440 Study Guide For Exam 1Document8 pagesAMIND 440 Study Guide For Exam 1WerchampiomsNo ratings yet

- First Amended Complaint - T. DukesDocument36 pagesFirst Amended Complaint - T. Dukesjulie9094No ratings yet

- Curfew Presentation Final 8 18 20 Item 21.1 and 21.2Document23 pagesCurfew Presentation Final 8 18 20 Item 21.1 and 21.2Erika EsquivelNo ratings yet

- Vance Letter To Blinken On Poland Media FreedomDocument3 pagesVance Letter To Blinken On Poland Media FreedomBreitbart News100% (1)

- List of Delhi Govt. DepartmentsDocument4 pagesList of Delhi Govt. DepartmentsHarish RanaNo ratings yet

- Perks of Being A Wallflower (Part 3)Document3 pagesPerks of Being A Wallflower (Part 3)Jen ZienkiewiczNo ratings yet

- ss8cg4 Judicial Branch - NotesDocument3 pagesss8cg4 Judicial Branch - Notesapi-291938215No ratings yet

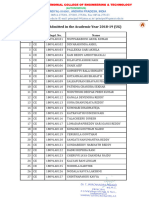

- Students Admitted in The Academic Year 2018-19 (UG) : S.No Branch Regd. No. NameDocument24 pagesStudents Admitted in The Academic Year 2018-19 (UG) : S.No Branch Regd. No. NameUpendra NeravatiNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines National Police Commission Philippine National Police Balatan Municipal Police Station Balatan, Camarines SurDocument12 pagesRepublic of The Philippines National Police Commission Philippine National Police Balatan Municipal Police Station Balatan, Camarines SurRitcheLanuzgaDoctoleroNo ratings yet

- TeTEXT OF THE HOMILY DELIVERED BY REV. FR. PATRICK OBAYOMI ON THE OCCASION OF THE 54TH BIRTHDAY OF MOST REV. DR. ALFRED ADEWALE MARTINS – ARCHBISHOP OF LAGOS. HOLY CROSS CATHEDRAL, LAGOS SATURDAY, 1ST JUNE, 2013.Document5 pagesTeTEXT OF THE HOMILY DELIVERED BY REV. FR. PATRICK OBAYOMI ON THE OCCASION OF THE 54TH BIRTHDAY OF MOST REV. DR. ALFRED ADEWALE MARTINS – ARCHBISHOP OF LAGOS. HOLY CROSS CATHEDRAL, LAGOS SATURDAY, 1ST JUNE, 2013.StanneitirepdfNo ratings yet

- Slovenian PhoenixDocument456 pagesSlovenian PhoenixToni PodrzajNo ratings yet

- Clinton Foundation - Charles Ortel AuditDocument18 pagesClinton Foundation - Charles Ortel AuditBigMamaTEA100% (1)

- Middle Georgia School Superintendent Comes Out As GayDocument3 pagesMiddle Georgia School Superintendent Comes Out As GayMatt HennieNo ratings yet

- The Timeline of Dream SMPDocument2 pagesThe Timeline of Dream SMPEunice VNo ratings yet

- 44 Tarnate v. DazaDocument2 pages44 Tarnate v. DazaRem SerranoNo ratings yet

- Andhra Pradesh Power Generation Corporation Limited Sri Damodaram Sanjeevaiah Thermal Power StationDocument1 pageAndhra Pradesh Power Generation Corporation Limited Sri Damodaram Sanjeevaiah Thermal Power StationkavyadeepamNo ratings yet

- Destroying Their Homes With Their Own Hands - by Sheikh Ibrahim Sulaiman Al-Rubaish (May Allah Protect Him)Document6 pagesDestroying Their Homes With Their Own Hands - by Sheikh Ibrahim Sulaiman Al-Rubaish (May Allah Protect Him)dfgldfkjNo ratings yet