Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nelson, J. Et Al,. 2013-Copiar

Uploaded by

SaulCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nelson, J. Et Al,. 2013-Copiar

Uploaded by

SaulCopyright:

Available Formats

©2013 Society of Economic Geologists, Inc.

Special Publication 17, pp. 53–109

Chapter 3

The Cordillera of British Columbia, Yukon, and Alaska: Tectonics and Metallogeny

JoAnne L. Nelson,1,† Maurice Colpron,2 and Steve Israel2

1 British Columbia Geological Survey, P.O. Box 9333, Stn Prov Gov’t, Victoria, British Columbia V8W 9N3, Canada

2 Yukon Geological Survey, P.O. Box 2703 (K-14), Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6, Canada

Abstract

The Cordilleran orogen of western Canada and Alaska records tectonic processes than span over 1.8 billion

years, from assembly of the Laurentian cratonic core of Ancestral North America in the Precambrian to sea-floor

spreading, subduction, and geometrically linked transform faulting along the modern continental margin. The

evolution of tectonic regimes, from Proterozoic intracratonic basin subsidence and Paleozoic rifting to construc-

tion of Mesozoic and younger intraoceanic and continent-margin arcs, has led to diverse metallogenetic styles.

The northern Cordillera consists of four large-scale paleogeographic realms. The Ancestral North American

(Laurentian) realm comprises 2.3 to 1.8 Ga cratonic basement, Paleoproterozoic through Triassic cover succes-

sions, and younger synorogenic clastic deposits. Terranes of the peri-Laurentian realm, although allochthonous,

have a northwestern Laurentian heritage. They include continental fragments, arcs, accompanying accretion-

ary complexes, and back-arc marginal ocean basins that developed off western (present coordinates) Ancestral

North America, in a setting similar to the modern western Pacific basin. Terranes of the Arctic-northeastern

Pacific realm include the following: pre-Devonian pericratonic and arc fragments that originated near the Bal-

tican and Siberian margins of the Arctic basin and Late Devonian to early Jurassic arc, back-arc, and accretion-

ary terranes that developed during transport into and within the northeastern paleo-Pacific basin. Some Arctic

realm terranes may have impinged on the outer peri-Laurentian margin in the Devonian. However, main-stage

accretion of the two realms to each other and to the Laurentian margin began in mid-Jurassic time and contin-

ued through the Cretaceous. Terranes of the Coastal realm occupy the western edge of the present continent;

they include later Mesozoic to Cenozoic accretionary prisms and seamounts that were scraped off of Pacific

oceanic plates during subduction beneath the margin of North America.

Each realm carries its own metallogenetic signature. Proterozoic basins of Ancestral North America host

polymetallic SEDEX, Cu-Au-U-Co–enriched breccias, MVT, and sedimentary copper deposits. Paleozoic syn-

genetic sulfides occur in continental rift and arc settings in Ancestral North America, the peri-Laurentian ter-

ranes, and in two of the older pericratonic Arctic terranes, Arctic Alaska, and Alexander. The early Mesozoic

peri-Laurentian arcs of Stikinia and Quesnellia host prolific porphyry Cu-Au and Cu-Mo and related precious

metal-enriched deposits. Superimposed postaccretionary magmatic arcs and compressional and extensional

tectonic regimes have also given rise to important mineral deposit suites, particularly gold, but also porphyries.

Very young (5 Ma) porphyry Cu deposits in northwestern Vancouver Island and sea-floor hotspring deposits

along the modern Juan de Fuca Ridge off the southwest coast of British Columbia show that Cordilleran metal-

logeny continues.

Introduction mineralization in Yukon adds an important new deposit

The Cordilleran orogen in British Columbia, Yukon, and model. Deposits of possible future economic importance that

Alaska (Fig. 1) has a tremendous mineral endowment. The form well-defined belts and clusters with clear tectonic con-

diversity of deposits, which range in age from 1.6 Ga to Recent, trols include: Irish-type syngenetic sulfides; Mississippi Val-

reflects equally diverse tectonic processes; thus, the orogen ley-type (MVT) Pb-Zn; skarns; carbonatites (REE, Nb-Ta);

is an excellent example of how metallogeny is governed by and iron-oxide copper-gold (IOCG).

tectonics. Herein we integrate the origins of major metallic The mineral deposits described herein are, of necessity, a

mineral deposits and mineral belts in the northern Cordillera small subset of the listings of deposits, prospects, and occur-

with its protracted tectonic history, updating Nelson and Col- rences in British Columbia (BC) MINFILE (>13,000), Yukon

pron (2007) to incorporate advances in mineral discovery and MINFILE (>2600), Alaska Resource Data File (>7,100), and

tectonic understanding in the last five years. the NORMIN database for the Mackenzie Mountains in

Mineral deposit types that include significant past and pres- Northwest Territories (~320). Mines and undeveloped min-

ent producing mines and/or major undeveloped resources eral resources were included in this discussion based on the

are as follows: porphyry Cu-Au, Cu-Mo, and Mo; epither- size and grade of individual deposits, on the cumulative eco-

mal, transitional, and intrusion-related gold; orogenic gold; nomic potential of belts and camps, and on qualitative criteria

volcanogenic massive sulfide (VMS); and sedimentary exha- such as perceived economic potential and genetic links to

lative (SEDEX). The recent discovery of Carlin-type gold large-scale tectonic events. Grade and tonnage values should

be taken as approximate; for up-to-date resource estimates,

the reader should consult company websites and current gov-

† Corresponding author: e-mail, joanne.nelson@gov.bc.ca ernment databases.

53

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

54 NELSON ET AL.

70

124°W

MORPHOGEOLOGICAL BELTS

116°W

108°

°W

132°W

°N

°W

140°W

W

156

2°

148

W

17

66

°N Arctic

Ocean

AG

FO

70°N

RE

AA

OM

LA

IN

ND

Ko Bro

EC

Seward bu oks

k

A

Range

Nome

fault

KY AG AA

a

AG

INSU

RB Pacific

Alask

Yukon

Kaltag Yukon Ocean

Rich

62

CO

IN

°N fault

Flats

TE

AG

LAR

ards

AS

AG

AG

NWT

66°N

RM

o

T

n tro

ON

4°W

Fairbanks

ugh

Ogilvie BE

TA

KY

16

Yukon-Tanana platform

Denali Upland LT

NE

F FW

NF Ran YT

ska ge NAb NAp

Ala BE

FwF B

EL LT

B

FW TT

EL

easte

NAp T

T

Selwyn

Ti

KB

fault

rn

fa

basin

n

KY WR Mackenzie

ul

tin

Mtn platform

t

a

58 tle Anchorage fa fa 62°N

°N Cas s CG ul

t YT QN ul NAb Yellowknife

t

ge

an Te M

R sl SM cE

Ca

PW in vo

PE Seward

ss

KS y

ia

YA AX

limit

YT

fau

platform

r

rde

lt

Bo Whitehorse YT

NAp NWT

Yukon

CF BC

CC SM

Maplat

Alberta

Yakutat

Ke F

YA

cD for

Th of 58°N

ch

Juneau ibe

on m

ika

rt

PW

Coastal

Prince William

ald

Pacific fa

Ocean ul NAc

PS

CG Chugach YT t

F

tro

CSF

ug

PR ST

h

CS

Al NAc

Co

Z

CR Crescent as

AX ka

rd

MT Methow

ille

ran

KY

Peri-Laurentian (Intermontane)

Koyukuk, Nyak, Togiak QN

RM

TkF

CD Cadwallader

T

NAp 54°N

Arctic - Northeast Pacific

PE Peninsular Edmonton

BR Bridge River

Qu

Prince Rupert def

Alexander orm

Insular

AX

een

CC Cache Creek atio

SM n

Co

WR Wrangellia

ast

Harrison WR ST

PF

HA AX

Ch

CC NAp

ar

KS Kluane, Windy, Coast

lo

CK Chilliwack

tte

YF NAb Calgary

pl

Angayucham/

ut

Northern Alaska

AG ST Stikinia fa Kootenay

on

Tozitna/Innoko Ancestral ul

FF

terrane

ic

Arctic-Alaska, t CD

AA Hammond QN Quesnellia North America co QN SM Bow

mp BR platform

RB Coldfoot, Ruby, NAb North America - deep 50°N WR lex

Seward OK Okanagan water (incl. Kootenay) OK

North America - Vancouver HA BC

FW Farewell YT Yukon-Tanana NAp

platform 0 100 200 300

North America - CK MT USA

116°W

KB Kilbuck SM Slide Mountain NAc

craton & cover km PR

Victoria

CR

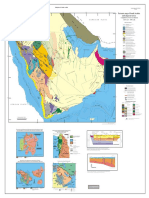

Fig. 1. Terranes of the Canadian-Alaskan Cordillera (after Colpron and Nelson, 2011a). Terranes are grouped in the

legend according to paleogeographic affinities shown in Figure 2. Inset shows morphogeologic belts of the northern Cordillera

after Gabrielse et al. (1991). Fault abbreviations: CF = Cassiar fault, CSF = Chatham Strait fault, FF = Fraser fault, FwF

= Farewell fault, KF = Kechika fault, NFF = Nixon Fork-Iditarod fault, PF = Pinchi fault, PSF = Peril Strait fault, NMRT

= northern Rocky Mountain trench, TkF = Takla-Finlay-Ingenika fault system, TT = Talkeetna thrust, YF = Yalakom fault.

Overview of Northern Cordilleran Tectonics Cordilleran orogen developed on and near the plate margin

that separates North America from the Pacific Ocean basin.

The North American Cordillera is one of the world’s clas-

Within the eastern part of the orogen are autochthonous and

sic accretionary orogens, where deformation, metamorphism, parautochthonous rocks of Ancestral North America (NAc,

and crustal growth accompanied continued subduction Fig. 1) and its overlying Proterozoic to Triassic cover (NAp

and accretion, rather than a process ending in continent- and NAb, Fig. 1). Farther west, most of British Columbia,

continent collision (Cawood et al., 2009). In this paper we Yukon, and Alaska are underlain by allochthonous terranes

focus on the Canadian and Alaskan Cordillera (Fig. 1). The (Fig. 1), defined here as rock assemblages of regional extent

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

THE CORDILLERA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, YUKON, AND ALASKA: TECTONICS AND METALLOGENY 55

within an orogenic belt that show internal geological consis- subdued region of islands and passages. The Boundary, St.

tency and that differ significantly from rock assemblages in Elias, Wrangell, Kenai-Chugach, and Alaska Ranges of south-

adjacent terranes. These allochthonous terranes include vol- ern Alaska (and western Yukon) owe their lofty heights to

canic, plutonic, sedimentary, and metamorphic assemblages ongoing terrane collision caused by subduction of the Pacific

that originated as magmatic arcs, accretionary complexes, plate.

microcontinents, and floors of ocean basins. Originating at

varying times between the Neoproterozoic and Cenozoic, the Cordilleran Terranes and Paleogeographic Realms

terranes accreted to western North America (present coor- The concept of tectonostratigraphic terranes (Fig. 1) was

dinates) in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. Much of the orogen first applied to tectonic analysis of the North American Cor-

is overlain by Jurassic and younger syn- and postaccretion- dillera in a series of groundbreaking papers in the early 1980s

ary siliciclastic deposits. All but the most cratonward part of (Coney et al., 1980; Jones et al., 1983), a concept that contin-

the orogen is intruded by postaccretionary plutons. In some ues as the basis for understanding Cordilleran geology. Ter-

regions, notably the southern interior of British Columbia, are rane names have become enshrined in the literature, and ter-

thick, relatively young subaerial volcanic cover strata. rane boundaries have, in most cases, shifted little since their

Braided sets of postaccretionary strike-slip faults transect original delineation. In the original definition, terranes were

the orogen (Fig. 1): the Tintina, Teslin, Thibert, Cassiar, Pin- characterized by internal homogeneity and continuity of stra-

chi, Takla, Yalakom, and Fraser faults in the center of the tigraphy, tectonic style and history separated by boundaries

orogen; on its oceanward side the Denali, Nixon Fork, Fare- that are not “conventional facies changes or unconformities”

well, Talkeetna, Castle Mountain, Chatham Strait, and Border (Coney et al., 1980), or as fault-bounded geologic entities of

Ranges faults; and the Kaltag and Kobuk faults in northern regional extent, each characterized by a geologic history that

Alaska. The Queen Charlotte and Border Ranges faults form is different from the histories of continguous terranes (Jones

the present margin between the North American and Pacific et al., 1983).

plates. Most of these faults parallel the present continent mar- The concept that each terrane is a fault-bounded entity,

gin, northwesterly in Canada and westerly and southwesterly unrelated to adjacent terranes, has come into question.

in Alaska. They record mainly dextral displacement, from Detailed studies have repeatedly documented primary strati-

mid-Cretaceous to, in the case of the Denali and Queen Char- graphic and intrusive links between some of the major ter-

lotte faults, present time. The total Cretaceous to Eocene ranes (e.g., Klepacki and Wheeler, 1985; Gardner et al., 1988;

offset on the Tintina-Teslin-Pinchi-Fraser system has been Colpron et al., 2007a) and pairing of arcs to accretionary belts

estimated at about 800 km (Gabrielse et al., 2006); the total (Nokleberg et al., 2005). A useful current definition needs to

offset on the Denali is about 300 to 400 km (Eisbacher, 1976; acknowledge the enduring importance of terranes as region-

Lowey, 1998). Motion on the Queen Charlotte and Border ally recognizable geologic entities, while accepting that they

Ranges faults has been of the order of thousands of kilome- may have developed as adjacent, locally linked tectonic ele-

ters. The tectonic configuration of central and western Alaska, ments. Investigation of interterrane relationships, along with

in which the Koyukuk and related late Mesozoic arc terranes faunal and isotopic evidence for paleogeographic affinities,

are enclosed in a V-shaped frame of older terranes (Fig. 1), form the basis for progress in understanding the tectonic evo-

may represent original salients and reentrants in the collision lution of the Cordillera.

zone and later dextral strike-slip movement (Box, 1985) and Based on region of origin, sets of related terranes in the

rotation of Arctic Alaska (Lawver and Scotese, 1990). northern Cordillera can be grouped into paleogeographic

The physiography of the northern Cordillera (Fig. 1 inset) realms (Fig. 2): (1) the Laurentian realm, which includes the

reflects the sum of the tectonic processes that created it. In autochthon and parautochthon of Ancestral North America;

British Columbia and southwestern Alberta, the Canadian (2) the peri-Laurentian realm of marginal arc, basin, and peri-

Rocky Mountains are made of continental margin sedimen- cratonic terranes and fore-arc accretionary complexes that

tary rocks of the Foreland belt that were detached from and evolved in proximity to the western (present coordinates)

thrusted and folded above Ancestral North America, mainly continent margin of Ancestral North America; (3) The Arctic-

in the Cretaceous. To the west, high mountains in the Omin- northeastern Pacific realm, including pre-Devonian terranes

eca belt, one of the two tectonic welts of Monger et al. (1982), of Baltican, Caledonian and/or Siberian affinity that origi-

reflect postaccretionary crustal thickening and transpression, nated in the present circum-Arctic region, and then evolved

which peaked in the Cretaceous and Tertiary transtensional at high latitudes in the ancestral northeastern Pacific basin,

collapse. along with younger associated arc and accretionary terranes;

West of the Omineca belt, the interior Intermontane and (4) the Coastal realm of later Mesozoic and Cenozoic

region, with its relatively subdued topography, continues into accretionary complexes that originated near or on the eastern

the Yukon plateau and Yukon-Tanana upland of east-central side of the Pacific basin and are accreted (or accreting) along

Alaska. Farther west, the Coast Mountain belt, the second the present North American-Pacific plate boundary (Fig. 2).

tectonic welt of Monger et al. (1982), consists of plutonic

rocks (with preintrusive metamorphic rocks) that form one of Laurentian realm

the largest batholiths in the world. This mountain belt con- The Laurentian realm refers to the western (present coor-

stitutes the root of a Late Jurassic to Eocene continental arc dinates) flank of Ancestral North America and the overly-

formed when Pacific plates subducted beneath the postac- ing strata that were deposited along its margin. The term

cretionary western flank of North America. The Insular belt “Laurentian” emphasizes the relationship of these rocks to

of British Columbia and southeastern Alaska is a relatively the ancient cratonic core; it parallels terminology used in

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

56 NELSON ET AL.

70

124°W

116°W

108°

180°

°W

90°W

132°W

90°E

°N

°W

140°W

W

156

2°

148

80°N

W

17

Arctic Ocean

Sea

66 nts Arctic Realm

°N Arctic B are

Ocean

La

60°N

70°N

ur

NE

en

an

Pacific

e

tia

Oc

Ko Bro

oks

tic

Tethyan

n

bu 30°N

k

lan

Range

At

fault

Pacific Ocean

62 Kaltag Yukon

°N fault

Flats

NWT

66°N

4°W

16

F

NF nge

Ra

ka

easte

as

Al

Ti

rn

n

De

tin

a

na

58 fa Wrangell fa 62°N

li

°N Chu ul Mts ul

g es i-

gac

h

t t

an na Te

Ke

fa

R Mt sl

in

ult

s

St. Elias

limit

fau

r

rde Mts

lt

Bo

Yukon NWT

CF BC

Bo

Alberta

un

Th of 58°N

da

ibe

KF

rt

ry

fa

Ra

ul

t

nge

Pacific

CSF

Ocean

CS

Al

Co

Z

as

ka

rd

ille

ran

RM

TkF

54°N

Qu

def

orm

een

atio

Coastal realm n

PF

Ch

Arctic - NE Pacific realm -

ar

lo

N.Alaska and Insular terranes

tte

YF

fa

Peri-Laurentian realm - ul

FF

t

Intermontane terranes

50°N

Laurentian realm - BC

Ancestral North America 0 100 200 300

USA

116°W

km

Fig. 2. Cordilleran terranes grouped by paleogeographic affinities. Paleogeographic affinity is assigned according to region

of origin in Paleozoic time, except for the Coastal terranes, which originated along the late Mesozoic-Cenozoic eastern Pacific

plate margin. Inset shows the main distribution of Paleozoic paleogeographic realms in the circum-Pacific region. Diago-

nal hatching indicates oceanic terranes in the peri-Laurentian and Arctic realms, horizontal hatching indicates accretionary

complex containing elements of Tethyan affinity (e.g. Cache Creek terrane). Fault abbreviations: CF = Cassiar fault, CSF =

Chatham Strait fault, FF = Fraser fault, KF = Kechika fault, NFF = Nixon Fork-Iditarod fault, PF = Pinchi fault, NMRT =

northern Rocky Mountain trench, TkF = Takla-Finlay-Ingenika fault system, YF = Yalakom fault.

the Canadian Appalachians (van Staal, 2007). The Paleozoic et al., 1991). However, its stratigraphy closely resembles that

architecture was one of long-lived generally shallow-water of the parautochthonous McEvoy and MacDonald platforms.

platforms (Mackenzie, McDonald, Bow, McEvoy) and deep- Similarly, stratigraphic ties have been demonstrated between

water basins (Selwyn, Kechika, Richardson; Fig. 1). Separated the Kootenay terrane and the adjacent Paleozoic continental

by the Tintina fault from the parautochthonous continental margin in southeastern British Columbia (Colpron and Price,

margin, the Cassiar platform in northern British Columbia 1995). In the Yukon-Tanana upland and northern Alaska

and southern Yukon has been classified as a terrane (Wheeler Range of eastern Alaska, a large tract of metamorphosed

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

THE CORDILLERA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, YUKON, AND ALASKA: TECTONICS AND METALLOGENY 57

pericratonic strata and Devonian plutons, formerly consid- through Cretaceous time, first in the paleo-Arctic basin and

ered part of the allochthonous Yukon-Tanana terrane, is now then in the northeastern Pacific basin. Arctic Alaska, Fare-

considered part of the western Laurentian margin (NAb on well, Kilbuck, and Alexander are of pericratonic or partly peri-

Fig. 1) based on its structural position and lack of late Paleo- cratonic origin, with strata as old as Proterozoic and detrital

zoic arc assemblages characteristic of the Yukon-Tanana ter- zircons as old as Archean, but they lack evidence of pre-Late

rane (Hansen and Dusel-Bacon, 1998; Dusel-Bacon et al., Devonian relationships to western Ancestral North America

2006; Nelson et al., 2006). or to the terranes of the peri-Laurentian realm. Instead, their

early Paleozoic faunal and isotopic affinities are with each

Peri-Laurentian realm other and with Siberia and/or Baltica (Bazard et al., 1995;

The peri-Laurentian realm includes the Slide Mountain, Soja and Antoshkina, 1997; Bradley et al., 2003; Amato et

Yukon-Tanana, Quesnel, Stikine, Cache Creek, and Bridge al., 2009; E.L. Miller et al., 2011; Beranek et al., 2013a, b).

River allochthonous terranes (Intermontane terranes of Mon- Silurian-Devonian migration of some or all of these pericra-

ger et al., 1982). The boundary between the peri-Laurentian tonic fragments westward through the paleo-Arctic basin is

realm and Ancestral North America is marked by discontinu- marked by influx of their signature detrital zircon populations

ous slivers of the Slide Mountain terrane, an oceanic assem- into Middle Devonian and younger siliciclastic strata of the

blage that exhibits late Paleozoic stratigraphic links both to northern Laurentian margin in the Canadian Arctic (Beranek

Ancestral North America (Klepacki and Wheeler, 1985), and et al., 2010; Lemieux et al., 2011; Anfinson et al., 2012a, b).

to the Yukon-Tanana terrane (Murphy et al., 2006). It con- Beginning in the Late Devonian, successive intraoceanic

tains interbedded mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORB) and Mis- arcs of the Insular terranes developed, in part on older crustal

sissippian chert and quartz clast-bearing sandstones and con- fragments, in the northeastern Pacific region. Devonian gab-

glomerates with northwestern Laurentian detrital zircon bros (S. Israel, unpub. data, 2013) and Pennsylvanian plutons

populations (Nelson, 1993; Roback et al., 1994; L. Beranek, (Gardner et al., 1988) link the Paleozoic arc of Wrangellia to

pers. comm., 2010). The Slide Mountain ocean, which may the pericratonic Alexander terrane of southwestern Yukon

have been up to 3,000 km wide by the mid-Permian, origi- and eastern Alaska. In turn, the Jurassic Talkeetna arc of the

nated as a Late Devonian to Permian back-arc basin (Nelson, Peninsular terrane is considered equivalent to the Bonanza

1993) that opened between the continental margin and Devo- arc, the youngest phase of Wrangellian arc activity (Clift et al.,

nian-Permian arcs to the west (present coordinates) in the 2005). In the northernmost Chugach terrane near the Border

Yukon-Tanana, Quesnel, and Stikine terranes (Colpron et al., Ranges fault, Early Jurassic blueschists and blocks of Permian

2007a). limestone with exotic, western Pacific faunas are thought to

Collectively, the peri-Laurentian arc terranes were origi- mark a subduction assemblage seaward (south) of the Penin-

nally bounded on their outer, oceanward margins by corre- sular terrane (Plafker et al., 1994). This accretionary complex,

sponding accretionary complexes represented by the Cache analogous to the Cache Creek terrane, represents a fore-arc

Creek and Bridge River terranes. These accretionary com- subduction complex of the Jurassic Talkeetna arc. Late Paleo-

plexes include slivers of high-pressure metamorphic rocks zoic and early Mesozoic faunas place the Insular terranes at

and, in the Cache Creek terrane, large carbonate bodies that varying latitudes in the northeastern Pacific region (Smith

cap seamounts or oceanic plateaus and contain Permian to et al., 2001; Belasky and Stevens, 2006). Their accretion to

Middle Triassic faunas that originated far out in the ancestral the outer edge of the peri-Laurentian terranes began in the

Pacific Ocean (Orchard et al., 2001). These features identify mid-Jurassic.

them as the sites of subduction of Pacific basin lithosphere. Arctic Alaska may have been the last of the Arctic-north-

For their entire history, arc terranes in the peri-Laurentian eastern Pacific realm terranes to find its resting place in the

realm show evidence of affinity for, and interactions with, the northern Cordillera, in concert with Cretaceous opening of

western Laurentian margin. Their evolution as a distinct realm the Canada basin (E.L. Miller et al., 2011). The Late Juras-

began with establishment of a continental arc on the western sic-Early Cretaceous Koyukuk arc of western Alaska (Fig.

margin of Ancestral North America in Devonian time, fol- 1) formed during subduction of the Angayucham oceanic

lowed by the Late Devonian to Permian opening of the Slide terrane, which separated it from pericratonic Arctic Alaska.

Mountain ocean and oceanward migration of the frontal arcs. This event ended with entry of Arctic Alaska and the adjoin-

Closure of the Slide Mountain ocean and initial reaccretion of ing Ruby terrane into the subduction zone and their collision

the inner margin of Yukon-Tanana and Quesnel terranes with the Koyukuk arc (Moore et al., 2004).

ocurred in the Triassic, and final accretion and amalgamation

took place in the mid-Jurassic, with closing of the Cache Coastal realm

Creek ocean, joining of Stikinia to Quesnellia, and trapping of The outermost, Coastal belt of terranes developed in the

the Cache Creek terrane between the two (Mihalynuk et al., eastern Pacific near or along the Cordilleran margin. The

1994a). terranes are relatively young (Mesozoic to Paleogene) and

include accreted Paleocene-Eocene seamounts of the Cres-

Arctic-northeastern Pacific realm cent terrane and accretionary complexes filled with sediments

This realm includes the Arctic Alaska, Farewell, Kilbuck, eroded from the emerging Cordillera (post-Early Jurassic

Ruby (in part), Angayucham, and Koyukuk terranes, and Chugach, Prince William, Pacific Rim, and Yakutat terranes).

also those in the Insular physiographic belt, the Alexander, Although they originated along the more-or-less present

Wrangell, and Peninsular terranes. Together these terranes margin of North America, some of the terranes in the Coastal

show evidence of a linked tectonic history from Proterozoic realm have undergone significant northward translation. Late

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

58 NELSON ET AL.

Cretaceous to Eocene clastic rocks of the Chugach and Prince and Parrish, 1991) and nearby Gold Creek gneiss (2.0–2.1 Ga

William terranes show detrital zircon populations likely of quartz diorite orthogneiss; Murphy et al., 1991); and (D) the

local provenance, whereas those in the Yakutat terrane were Sifton Ranges of north-central British Columbia (SR; ca.

probably derived from southwestern North America (J. 1.85 Ga granitic orthogneiss; Evenchick et al., 1984). These

Garver, pers. commun., 2013). Paleomagnetic data also indi- basement complexes match well the ages and composition of

cate large translations, of the order of 13° to 23° (Bol et al., domains in the adjacent western Laurentian craton (Fig. 3).

1992; Gallen, 2008; Housen et al., 2008). Most of these basement occurrences are involved in the Cor-

dilleran deformation and probably originated 100 to 200 km

Laurentian Realm: Ancestral North America southwest of their present exposures (e.g. McDonough and

Parrish, 1991). It is notable that the only occurrence of

Western extent of Laurentian crust Archean basement, in the Priest River complex of Idaho, lies

The Cordilleran orogen was constructed along the western south of the projected boundary between Archean and Paleo-

margin (present-day coordinates) of the Laurentian craton, proterozoic domains in the Alberta basement to the east (Red

the Precambrian core of the North American continent. Lau- Deer zone, Fig. 3).

rentia was assembled through the progressive accretion of 3. Initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios from Mesozoic granitoids sug-

microcontinents and magmatic arcs beginning in the Archean, gest that Precambrian crust extends at least as far west as

culminating with the Paleoproterozoic “Hudsonian orogeny” the Monashee complex in southern British Columbia (MC

(2.0–1.8 Ga), and concluding in the early Mesoproterozoic on Fig. 3) and the Teslin fault in Yukon (Armstrong, 1988).

(Hoffman, 1988). These successive orogenic events have A ratio greater than 0.706 indicates melting or assimilation

imparted a tectonic grain to the cratonic basement that is of older (Precambrian) crust or lithospheric mantle, whereas

well imaged in the regional aeromagnetic map of western ratios lower than 0.704 reflects magma genesis in more juve-

Canada (Fig. 3). At the Cordilleran deformation front, prom- nile, Phanerozoic crust or lithospheric mantle (Armstrong,

inent structural trends in the cratonic basement are mainly 1988, p. 77). The 87Sr/86Sr isopleths shown on Figure 3 are

northeasterly and at a high angle to the Cordilleran grain, derived primarily from granitic rocks 90 Ma and older in the

south of 56°N (Fig. 3; Ross, 2002). To the north, in Yukon eastern half of the orogen (Armstrong, 1988) and have thus

and Northwest Territories, the Cordilleran structural grain been translated northeasterly by as much as 100 to 200 km

follows the arcuate trend of Paleoproterozoic basement during Late Cretaceous to Paleocene development of the

domains in the subsurface of northwestern Canada (Aspler et Foreland belt. The assimilation of older crustal components

al., 2003). Basement structures evident on the aeromagnetic is also evident in the common occurrence of Paleoproterozoic

map of the Alberta basement can be traced confidently and Archean inherited zircons in Cordilleran granitic rocks.

beneath the Cordillera south of 56°N as far west as the south- 4. Seismic reflection and refraction profiles acquired by the

ern Rocky Mountain trench (SRMT on Fig. 3), at which point Lithoprobe program indicate that North American Precam-

the magnetic signature is overprinted by Cordilleran meta- brian crust presently extends beneath much of the Cordille-

morphism and magmatism of the Omineca belt. Several lines ran orogen. In seismic profiles of the southern Canadian Cor-

of evidence, however, suggest that western Laurentian Pre- dillera, the North American basement is inferred to extend

cambrian crust extends farther west beneath the orogen as far west as the Fraser fault (Cook et al., 1992; Clowes et

(Ross, 1991). al., 1995). In the northern Cordillera, autochthonous North

America is interpreted to project beneath the orogen as far

1. Rapid thickness and facies changes in Mesoproterozoic west as surface exposure of the Cache Creek terrane (Figs.

to early Paleozoic strata of the Ancestral North American 1, 3; Cook et al., 2004; Clowes et al., 2005; Evenchick et al.,

margin locally occur across NE-trending structures that are 2005).

transverse to the Cordilleran tectonic grain and have been

interpreted as southwest continuations of major structures in These observations collectively suggest that Precambrian

the cratonic basement to the east (Fig. 3). In southern Brit- crust of western Laurentian affinity extends beneath the

ish Columbia, the Moyie-Dibble Creek fault (MDC in Fig. 3) eastern half of the present-day Cordillera of British Colum-

and related structures probably represent surface expressions bia and Yukon (Fig. 3). The western extension of the cra-

of the Vulcan Low to the east (e.g., Price, 1981; McMechan, tonic basement and its contained crustal structures played an

2012). In the north, the NE-trending Hay River, Liard, and important role in the genesis and localization of some of the

Fort Norman lines controlled thickness and facies in both mineral deposits in the eastern Cordillera. Furthermore, the

autochthonous and parautochthonous Neoproterozoic and alignment of depositional facies and structural trends in par-

early Paleozoic strata of the Ancestral North American margin autochthonous strata of Ancestral North America with base-

(Cecile et al., 1997). ment structures of the northwestern Laurentian craton limit

2. Crystalline basement exposures have been documented the amount of lateral translation that could have occurred

in four locations at low structural levels within the Omineca within the western Laurentian realm. An additional constraint

belt: (A) the Priest River complex in northern Idaho (PRC on on paleogeographic reconstructions of the continent margin

Fig. 3; ca. 2.65 Ga augen orthogneiss; Doughty et al., 1998); is provided by detrital zircon populations of Ancestral North

(B) the Monashee complex (MC; ca. 1.86–2.10 Ga augen American strata, which generally reflect a mixture of Paleo-

orthogneiss and granodiorite gneiss; Crowley, 1999); (C) the proterozoic and Archean sources that closely match subjacent

Malton complex (MG; ca. 1.87 Ga, Yellowjacket augen basement domains of northwestern Laurentia (Fig. 3; Gehrels

orthogneiss and Bulldog granodiorite gneiss; McDonough et al., 1995; Gehrels and Ross, 1998).

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

THE CORDILLERA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, YUKON, AND ALASKA: TECTONICS AND METALLOGENY 59

110°W

100°W

120°W

130°W

°W

70°N

140

CBL

Ho

tta

h

Gre

65 Sim at

°N

t pso

Thelon

For east

n

ern Rae

>2.5 Ga

Slave

Bear

65°N

0.

70

Te

5 an

s

>2.5 Ga

1.78-1.87 G

lin

Ti

m

or

n

Hottah

tin

.N

Ft

a

Nahann

0.707

limit ne

a zo

1.84-1

Rae

i

.88 Ga

60° >2.5 Ga

fau

SZ Hearne

N

2.1-2.3 Ga

of

L i c

lt

GS on

fau

0.705

>2.5 Ga

ct

lt

te 60°N

d

W iar

on

L

0.704

ES FN

mps

SR

TE Taltson

RN Hottah

d

t Si

bir

For

ow

Cordilleran

1.93-

ED

Sn

0.7

1.97 Ga

RF

GE

Buffalo

07

H Head

Chi

55°

N 1.99-2.32 Ga

nch

Nova

OF

>2.5 Ga? KD

aga

1.90-

1.98 Ga a 55°N

G

KL d 5

ef .8

o 2.08- -1

rm 2.18 Ga 78

1.

0.704

LAURENTIAN

at

io Hearne

n Trans-Hudson

0.7

Ga be

0.7

Wabamun a >2.5 Ga 1.8-1.9 Ga

<2 com

04

~2.32 G

07

.3

L a

TL

y

0.

MG

be

Frase

70

im

Z

7

50°N

RD

SR

R

0.7

M

r fault

MC

04

T

CRU

an

Vulc

50°N

ST

DC Medicine Hat block

M 2.6-3.3 Ga 0 100 200 300

110°W

120°W

W

T Z

130°

PRC GF km

Fig. 3. Residual total field aeromagnetic map of western Canada, showing Precambrian basement domains of the western

Laurentian craton with respect to the Cordilleran orogen (eastern limit of Cordilleran deformation indicated by white line).

Precambrian basement domains are after Hoffman (1988), Ross et al. (1991), Villeneuve et al. (1993), Ross (2002), Hope and

Eaton (2002), and Aspler et al. (2003). Aeromagnetic image is derived from a 2010 compilation in the Canadian aeromag-

netic database (http://gdr.agg.nrcan.gc.ca/geodap). Precambrian domain boundaries are delineated by dotted lines; major

basement structures are shown by short dashed lines. Some major structures extend beneath the Cordillera, including the

Moyie-Dibble Creek fault (MDC) and related structures in the south (after McMechan, 2012), and the Liard and Fort Nor-

man lines in the north (after Cecile et al., 1997). Stars show location of Precambrian basement exposures in the Omineca belt:

MC = Monashee complex (1.86–2.10 Ga; Crowley, 1999); MG = Malton complex and Gold Creek gneiss (ca. 1.87–2.09 Ga;

McDonough and Parrish, 1991; Murphy et al., 1991); PRC = Priest River complex (ca. 2.65 Ga; Doughty et al., 1998); SR =

Sifton Ranges (ca. 1.85 Ga; Evenchick et al., 1984). Initial 87Sr/86Sr ratio isopleths for Mesozoic granitic rocks of the Cordillera

(dashed blue lines) are after Armstrong (1988). Dashed brown line indicates inferred extent of North American crust beneath

the Cordilleran orogen from geophysical, geochemical, and geological data discussed in text. Other abbreviations: CBL =

Cape Bathurst line, FN = Fort Nelson high, GFTZ = Great Falls tectonic zone, GSLSZ = Great Slave Lake shear zone, HRF

= Hay River fault, KD = Ksituan domain, KL = Kiskatinaw low (1.90–1.98 Ga), LD = Lacombe domain, RDZ = Red Deer

zone, SRMT = Southern Rocky Mountain trench, TL = Thorsby low (1.91–2.38 Ga).

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

60 NELSON ET AL.

Proterozoic basins of the western Laurentian realm Supergroup (Gayna River deposits). Rocks of the Muskwa

(1.71–0.78 Ga) basin are host to the Churchill Copper vein systems. The Belt-

Following the Hudsonian orogeny (2.0 –1.8 Ga), but before Purcell basin contains the giant Sullivan SEDEX deposit.

breakup of the western margin of Ancestral North America Wernecke-Mackenzie Mountains: Successions in the Wer-

(780–570 Ma), sedimentary successions accumulated in three necke, Ogilvie, and Mackenzie Mountains of Yukon and

main areas of the northern Cordillera: the Wernecke-Mack- Northwest Territories (Fig. 4), record multiple episodes of

enzie Mountains, the Muskwa basin, and the Belt-Purcell sedimentation punctuated by orogenesis, magmatism, and

basin (Figs. 4, 5; Successions A and B of G.M. Young et al., prolonged subaerial exposure (e.g., Thorkelson et al., 2005).

1979). All three areas contain significant mineral deposits, The 13-km-thick Wernecke Supergroup (post-1.64, pre-

each of distinct types (Nokleberg et al., 2005). The Cu-Au- 1.60 Ga; Thorkelson et al., 2001a; Furlanetto et al., 2012;

U-Co-enriched Wernecke breccias crosscut older strata of the Fig. 5) was deposited in a broadly subsiding marine basin

Wernecke Supergoup and Mississippi Valley-type mineraliza- floored by extending crystalline basement. Wernecke Super-

tion occurs in younger strata of the Mackenzie Mountains group strata were deformed and metamorphosed during the

124°W

116°W

108°

132°W

°W

140°W

148

W

Arctic

Ocean

70°N

Shaler

basin

a

ine

Alask

Yukon

erm

pp

/Co

l Lk 66°N

Wernecke ma

Dis

NWT

Wernecke breccias Gayna

basin River

easte

Hart

River

rn

Mackenzie

Mtns basin 62°N

limit

Yukon NWT

BC

Alberta

Muskwa

of Churchill 58°N

basin Copper

Pacific

Ocean

Al

Co

as

ka

rd

ille

ran

54°N

Proterozoic

sulfide deposits def

orm

atio

n

Mackenzie Mountains basin

Belt-Purcell basin

Muskwa basin

Sullivan

Wernecke basin Mine

Extent of Neoproterozoic Fig. 4. Paleoproterozoic to early Neoproterozoic basins

and older ‘basement’ of 0 100 200 300 Belt- and mineral deposits of northwestern Laurentia. Wernecke

western Laurentian affinity USA

Purcell breccia occurrences from Lefebure et al. (2005). Light blue

km

basin area shows distribution of rocks with Laurentian ancestry.

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

THE CORDILLERA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, YUKON, AND ALASKA: TECTONICS AND METALLOGENY 61

Southern B.C. Yukon - SE-vergent Racklan orogeny at ca. 1.6 Ga, an event that has

Northwest U.S. Northern B.C. western NWT been related to accretion of a cryptic terrane comprising ca.

600

Marinoan 1.71 Ga magmatic rocks (Bonnetia of Furlanetto et al., 2012).

Windermere Spgp

A widespread hydrothermal event at ca. 1599 to 1595 Ma post-

Windermere

Windermere

Hay Creek Gp

breakup

Horsethief Ck Ingenika Gp

Group Crest

dates the Racklan orogeny and led to emplacement of the Wer-

??

Gataga Rapitan Gp necke breccias (Thorkelson et al., 2001b). Hunt et al. (2007,

700 Irene Toby Fm Misinchinka Gp Sturtian 2011) favor a nonmagmatic origin for the Wernecke breccias

NEOPROTEROZOIC

Mt Harper Gp

Coates Lk Gp. in which fluids derived from meta-evaporites near the base

Callison Lk dol. of the Wernecke Supergroup caused periodic overpressuring

RODINIA

???

800

Hottah Little Dal basalt

Tsezotene sills of formational and metamorphic water. The breccias form an

Mackenzie Mtns spgp

Churchill Cu

Mount Nelson Fm Little Dal Gp extensive, curvilinear, E-W–trending belt that corresponds to

Gayna River Wernecke Supergroup exposures in the Wernecke and Ogil-

(Paleozoic?)

vie Mountains of north-central Yukon (Fig. 4); associated

Katherine Gp

900 deposits are considered IOCG-type (iron-oxide copper-gold;

Lefebure et al., 2005; Corriveau, 2007). Significant parallels

??? Hematite Ck Gp can be drawn between the Wernecke breccia deposits and the

giant Olympic Dam deposit in Australia (Bell and Jefferson

1000

1987), and Thorkelson et al. (2001b) favor a pre-Rodinia con-

metamorphism

in Belt Spgp Pinguicula Gp, tinental reconstruction that places them ~1,000 km from each

lower Fifteenmile

???

other in a single, contiguous early Mesoproterozoic supercon-

1100 granitoid clasts

in Coates Lk

assembly tinent. However, pre-Rodinian and Rodinian reconstructions

diatreme

are contentious and poorly constrained (see below and Fig. 6),

and in contrast to the Wernecke breccias, the Olympic Dam

deposit appears to have been related to continental arc mag-

1200 matism (Ferris and Schwartz, 2003).

???

MESOPROTEROZOIC

Bear River

Following a ca. 220 m.y. hiatus, rocks of the Wernecke

Supergroup were intruded by the ca. 1.38 Ga Hart River

East Kootenay

1300 sills and overlain by their volcanic equivalents (G. Abbott,

1997; Thorkelson et al., 2005). The Hart River massive sul-

metamorphism

fide deposit (Figs. 4, 5) is the only known significant occur-

in Belt Spgp Hart River rence associated with this phase of magmatism. The overlying

1400 Hart River VMS

3.5-km-thick Pinguicula Group was originally interpreted to

Belt-Purcell Muskwa

Supergroup be intruded at its base by the Hart River sills. However, recent

assemblage

Sullivan Moyie sills examination of contact relationships shows that the Pinguicula

1500 Group unconformably overlies the Hart River sills and their

Wernecke Supergroup host (Medig et al., 2010). Siliciclastic

and carbonate rocks of the Pinguicula Group were depos-

Racklan

Wernecke

breccias ited in a slope to deep-basin environment (Thorkelson, 2000;

1600 GL Medig et al., 2010, 2012). Preliminary detrital zircon analy-

Wernecke Q

Supergroup FL ses suggest that strata of the Pinguicula Group are younger

than ca. 1150 Ma (Fig. 5; Medig et al., 2012). The Pinguicula

PALEOPROTEROZOIC

Group is unconformably overlain by shallow-water siliciclastic

1700 “Bonnetia”

and carbonate rocks of the Hematite Creek Group, a west-

ern basal succession of the Mackenzie Mountains Supergroup

(Thorkelson, 2000; Turner, 2011), and part of a widespread

1800 deformation &

Neoproterozoic depocentre in northwestern Laurentia (e.g.

mineral deposit

metamorphism Rainbird et al., 1996). The Mackenzie Mountains Supergroup

Ma felsic magmatism glacial deposit (ca. 1.0–0.78 Ga; up to 4 km thick; Fig. 5; Long and Turner,

2012; Turner and Long, 2012) includes a lower succession

of shallow-marine to fluvial mudstone, siltstone, and quartz

arenite that contains abundant Mesoproterozoic detrital zir-

cons (1.25–1.0 Ga). These strata are interpreted to form part

Fig. 5. Generalized stratigraphy of Proterozoic precursor basins in the

Canadian Cordillera. Modified after Thorkelson et al. (2001a, 2005), Turner

of a pan-continental braided river system with sources in the

(2011), Furlanetto et al. (2012), F.A. Macdonald et al. (2012) and Martel et Grenville orogen of southeastern Laurentia (Rainbird et al.,

al. (2012). Bonnetia is a cryptic terrane represented by ca. 1.71 Ga igneous 1997). Overlying carbonate and minor evaporite of the Little

clasts in Wernecke breccias and inferred to have been accreted to northwest- Dal Group record deposition in an intracratonic basin. Reef

ern Laurentia during the ca. 1.6 Ga Racklan orogeny. Timing of assembly mounds in the Little Dal Group contain the only known sig-

and breakup of Rodinia are shown by arrows at right. Relative stratigraphic

position of major mineral deposits discussed in text is also shown. Abbrevia- nificant mineralization in the Mackenzie Mountains Super-

tions: FL = Fairchild Lake Group, GL = Gillespie Lake Group, Q = Quartet group, the Gayna River deposits, a cluster of MVT deposits

Group. totaling some 50 Mt averaging 4.7% Zn (Figs. 4, 5). The age

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

62 NELSON ET AL.

a) SWEAT b) AUSWUS

Moores (1991) Karlstrom et al. (1999)

Hoffman (1991) Burrett & Berry (2000)

Australia

Australia

Antarctica

Grenville

Olympic Dam

Olympic Dam

Antarctica

G

Wernecke

re

Wernecke

n

vi

Sullivan

lle

Sullivan

equator equator

b

Siberia el

t Siberia

be

Laurentia

lt

Laurentia

Baltica Baltica

1000 km

c) Siberian connection d) South China in Rodinia

Sears & Price (2000, 2003a,b) Li et al. (1995, 2008)

Australia

Siberia

Antarctica

Australia

Olympic Dam

S China

G

re

Olympic Dam Antarctica

nv

Wernecke

Ta

im

i

yr

Siberia

lle

tro

equator

ug

Wernecke

h

Udzha Sullivan

trough

be

Sullivan G

equator re

lt

Laurentia

n

vi

Laurentia lle

Baltica Baltica

be

lt

Proterozoic basins

sediment transport 1.5-1.4 Ga Belt-Purcell

-

direction 1.45 Ga Sullivan SEDEX 1.7-1.6 Ga Wernecke,

- Mt. Isa/McArthur

inferred edge of 1.5 Ga mafic dikes Precambrian domains (craton)

craton 1.5-1.4 Ga granite- 1.4-1.0 Ga - Grenville, Sveconorwegian

Phanerozoic rhyolite province

orogenic belt 1.6-1.4 Ga - Pinwarian-Telemarkian

1.6 Ga IOCG breccias 1.8-1.6 Ga - Yavapai-Mazatzal

2.0-1.8 Ga - Trans-Hudson, Svecofennian

Archean (>2.5 Ga) - Superior, Kola-Karelian

Fig. 6. Alternative models for Mesoproterozoic reconstruction of Laurentia within the supercontinent Rodinia (ca. 1.0

Ga). (a) The SWEAT hypothesis (Hoffman, 1991; Moores, 1991) juxtaposes Australia with northwestern Laurentia (modern

reference frame). This reconstruction provides the best fit between Mesoproterozoic IOCG occurrences in northwestern

Canada and Australia, and a “western” Australian source for 1.6 to 1.5 Ga zircons in Mesoproterozoic strata of the Belt-Purcell

Supergroup (Ross et al., 1992) and the Pinguicula Group (Medig et al., 2012). (b) The AUSWUS connection (Karlstrom et

al., 1999; Burrett and Berry, 2000) juxtaposes Australia to the southwestern United States, leaving the northwestern Lau-

rentian margin opened (or juxtaposed to an unspecified craton). This reconstruction also provides adequate source regions

in Australia for 1.6 to 1.5 Ga zircons. Reconstruction of Siberia against the northern Laurentia margin in A and B is after

Rainbird et al. (1998) and Khudoley et al. (2001). (c) The Siberian connection of Sears and Price (2000, 2003a, b) juxtaposes

the Archean Aldan shield and Wyoming craton; 1.6 to 1.5 Ga zircons are sourced in the mid-continent granite-rhyolite prov-

ince of Laurentia and transported via the Udzha trough (Siberia) into the Belt-Purcell basin. This reconstruction also aligns

1.5 Ga mafic dikes and sills in western United States (including the Moyie sills) with similar dikes in northern Siberia. In

this model, the northern Laurentian margin is open and there is no source region for 1.6 to 1.5 Ga zircons in the Wernecke

Mountains. (d) The reconstruction of Li et al. (1995, 2008) places the South China craton between Laurentia and Australia.

This model extends Grenvillian orogenesis in the Siboa belt and thus provides the closest fit for hints of Grenvillian tectonism

in the North American Cordillera (Milidragovic et al., 2011). Only continents that have a postulated relationship with western

Laurentia are shown here.

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

THE CORDILLERA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, YUKON, AND ALASKA: TECTONICS AND METALLOGENY 63

of the Gayna River deposits is not well constrained. Kesler extension related to the ca. 1.37 Ga East Kootenay “orogeny”

(2002) related their formation to penecontemporaneous (McMechan and Price, 1982; Doughty and Chamberlain,

basinal fluids, in which case mineralization would have been 1996; H.E. Anderson and Parrish, 2000; Zirakparvar et al.,

early Neoproterozoic, but lead isotopes from Gayna River 2010; Nesheim et al., 2012), an event that is broadly coeval

and other Zn-Pb occurrences in the Mackenzie Mountains with Hart River magmatism in Yukon (Fig. 5). The record

favor a Paleozoic event (or events) possibly related to SEDEX for the next ~300 m.y. is sparse in the northern Cordillera;

mineralization in the Selwyn basin (see below; Godwin and although hints of Mesoproterozoic magmatism and possible

Sinclair, 1982; Ootes et al., 2013). Turner and Long (2008) Grenvillian-age tectonism are reported from an increasing

have suggested that deposition of the Mackenzie Moun- number of localities along the Cordillera (e.g., H.E. Anderson

tains Supergroup occurred in an extensional basin, probably and Parrish, 2000; Zirakparvar et al., 2010; Milidragovic et al.,

a precursor to the late Neoproterozoic-Cambrian breakup 2011; Nesheim et al., 2012), their scale is insignificant com-

of Rodinia. They interpret abrupt thickness and lithofacies pared with the Grenville orogen, which in Ancestral North

variations to mark the locus of transverse, NE-striking growth America extends from Labrador to western Mexico.

faults, which subsequently focused fluid flow and the younger

mineralization. Laurentia in Rodinia

Muskwa basin: The age of the westward-thickening sedi- By the end of the Mesoproterozoic (ca. 1.0 Ga), the Pre-

mentary prism in the Muskwa basin is loosely bracketed cambrian cratons were assembled to form the supercontinent

between 1766 Ma, the age of its youngest detrital zircons, and Rodinia (e.g., Hoffman, 1991; Moores, 1991; Li et al., 2008).

crosscutting 779 Ma diabase dikes (Ross et al., 2001). Like the Several reconstructions have been proposed, most placing

Wernecke basin, it has been interpreted as an intracratonic Laurentia within the core of the supercontinent, but all pro-

basin (Long et al., 1999). The Churchill Cu-bearing quartz- posing different craton(s) as conjugate to the Neoproterozoic

ankerite veins (Fig. 4) are cospatial with abundant diabase western Laurentian margin (Fig. 6). These reconstructions

dikes in a generally NE-striking array that postdates a phase have implications for understanding Proterozoic basin devel-

of NE-vergent folding. Ross et al. (2001) suggested that both opment, sediment source regions, the genesis of associated

veins and dikes relate to the onset of Neoproterozoic rifting ore deposits, and the identification of potential global metal-

that fragmented Rodinia. lotects. Are the Wernecke breccias close cousins to IOCG

Belt-Purcell basin: The Mesoproterozoic Belt-Purcell basin deposits in Australia? Is there a continuation of the Belt-Pur-

is host to one of Canada’s stellar deposits, the 160 Mt Sullivan cell basin on some other continent, with its promise of pro-

Pb-Zn-Ag orebody (Figs. 4, 5), which was mined continuously spective ground for the discovery of another giant SEDEX

from 1914 until closure in 2001. The Belt-Purcell Supergroup deposit like Sullivan?

is significantly younger than the Wernecke Supergroup (Fig.

5; 1.47–1.40 Ga, Ross and Villeneuve, 2003; 1.50–1.32 Ga, Protracted breakup of western Laurentia: 780–570 Ma

Lydon, 2007). It also shows a much more active style of depo- In western Laurentia, extension that would eventually lead

sition than the Wernecke and Muskwa basins, with rapid rates to the demise of Rodinia probably began with deposition of

of sedimentation (18–20 km thick; Lydon, 2007), mafic vol- lower Neoproterozoic strata of the Mackenzie Mountains

canic rocks and sill complexes, and well-defined intrabasinal Supergroup (Fig. 5; Turner and Long, 2008) and magmatism

syndepositional faults (Ross and Villeneuve, 2003). Facies of the Gunbarrel large igneous province (LIP; Harlan et al.,

and paleocurrent indicators, as well as detrital zircon popula- 2003), but this attempt at rifting apparently failed. It was only

tions of 1.61 to 1.50 Ga that are not represented in the nearby in late Neoproterozoic to Early Cambrian time that the west-

Laurentian basement, are interpreted by Ross and Villeneuve ern margin of Ancestral North America was born as Laurentia

(2003) to indicate non-Laurentian western sources that were broke out of Rodinia and the paleo-Pacific ocean opened—

removed during late Proterozoic or earlier continental rifting the ocean that would by late Paleozoic time become the world

(Fig. 6a, b). The presence of detrital grains identical in age to ocean, Panthalassa (Scotese, 2002).

sedimentation in the Belt-Purcell basin suggests that it may The creation of the margin was protracted and involved at

have abutted an active magmatic belt on its western side (Ross least two main episodes of rifting (see Colpron et al., 2002;

et al., 1992; Ross and Villeneuve, 2003). This basin provided Lund et al., 2003, 2010). An earlier phase (ca. 723–716 Ma,

the tectonic setting for accumulation of syngenetic, sediment- Cryogenian; F.A. Macdonald et al., 2010, 2012) is shown in

hosted massive sulfide ore. The Sullivan deposit, dated at 1.47 coarse, immature siliciclastic deposits and local volcanic rocks

to 1.45 Ga by Sm-Nd methods (Jiang et al., 2000), is associ- of the Windermere Supergroup, and widespread LIP mag-

ated with a NE-striking synsedimentary fault array, including matism of the Franklin event (Heaman et al., 1992). The final

the St. Mary, Kimberley, and Moyie-Dibble Creek faults (Höy phase is recorded by upper Neoproterozoic (Ediacaran) to

et al., 2000; MDC, Fig. 3) as well as with the voluminous syn- Lower Cambrian Hamill-Gog Group strata of southeastern

sedimentary mafic Moyie sills. The NE-striking faults align British Columbia (e.g., Devlin and Bond, 1988; Warren, 1997;

with the Vulcan Low to the east (Fig. 3), at a high angle to the Colpron et al., 2002; ca. 570–540 Ma).

NNW-trending basin margin, as well as to trends of rift gra- Rifting was coeval with at least two global Neoproterozoic

ben (Price, 1981; McMechan, 2012). Lead-zinc-silver miner- glaciations (Rapitan [Sturtian] and Ice Brook [Marinoan];

alization with characteristic tourmaline alteration is localized the Snowball Earth events of Hoffman et al., 1998; Hoffman

where the cross-faults offset rift basins (Höy et al., 2000). and Schrag, 2002; Arnaud et al., 2011). In the south, ther-

Deposition in the Belt-Purcell basin ended with an epi- mal subsidence associated with the later rifting event began

sode of bimodal magmatism, burial metamorphism, and about 575 Ma (Bond and Kominz, 1984). The lower part of

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

64 NELSON ET AL.

the Hamill-Gog Group lies unconformably on the Winder- Early Paleozoic continental margin

mere, and strong facies and thickness variations and signifi- Following breakup, intermittent extension continued

cant local accumulations of basalt suggest that it was depos- to shape the western margin of Ancestral North America

ited in a series of N-trending rift gräben (Warren, 1997). A throughout the early Paleozoic. Extension was accompanied

ca. 570 Ma dike related to this phase of magmatism dates the by four major volcanic pulses and locally related diatremes

second pulse of rifting in the southern Canadian Cordillera and syenite, in Cambrian, Silurian, Early to Middle Ordovi-

(Colpron et al., 2002). cian, and Middle to Late Devonian (Fig. 8; Goodfellow et al.,

During the Ediacaran, continental extension is recorded 1995; Lund et al., 2010; Millonig et al., 2012). The Selwyn

in three grand-cycles in the upper Windermere Supergroup basin was a deep-marine embayment in the northern conti-

of the northern Cordillera (Narbonne and Aitken, 1995; Dal- nental margin that was initiated in the Neoproterozoic with

rymple and Narbonne, 1996; Turner et al., 2011). Deposi- deposition of the Hyland Group and persisted throughout

tion of the coarse, immature siliciclastic rocks of the Hyland early Paleozoic (Gordey and Anderson, 1993). Alkalic to ultra-

Group in Selwyn basin probably also began at that time (Fig. potassic volcanic rocks occur throughout the Selwyn basin

7; Fritz et al., 1991; Gordey and Anderson, 1993; Colpron et and its southern extension, the Kechika trough, and within

al., 2013). Intermittent extension between these two major basinal successions of northern Yukon (Fig. 8; Goodfellow et

episodes of rifting is indicated by sporadic alkaline magma- al., 1995). The strong structural control in the development of

tism along the length of the Cordilleran margin (e.g., Lund Selwyn basin is particularly evident along its northern edge,

et al., 2003, 2010; Pigage and Mortensen, 2004; Millonig et where abrupt facies changes and sporadic magmatism in Neo-

al., 2012). proterozoic to Devonian strata are localized near the Dawson

Although it records a major continental rift event, the Win- fault (Fig. 7a). The Dawson fault is a deep-seated, long-lived

dermere Supergroup hosts only limited syngenetic mineral- structure with a compound history of extension and com-

ization, all of which is in the far northern Cordillera of Yukon pression from the Neoproterozoic to Mesozoic, and perhaps

and NWT. Mineralization in the Redstone copper belt, in the Cenozoic (G. Abbott, 1997; Colpron et al., 2013). This abrupt

Mackenzie Mountains, is hosted by carbonate rocks of the platform to deep-water transition contrasts with the more typ-

Coates Lake Group, a succession of evaporite, redbed (sand- ical interfingering of facies observed between Selwyn basin

stone, conglomerate), and carbonate rocks deposited in fault- and Mackenzie platform in eastern Yukon and NWT (Fig. 7b).

bounded gräben that developed during the early stages of Along its southern edge, the platform to basin transition shifts

Windermere rifting (Figs. 7, 8; Jefferson and Ruelle, 1986; nearly 200 km to the west along the Yukon-British Colum-

Ootes et al., 2013). The copper mineralization is diagenetic bia border (Fig. 8), a feature that is attributed to reactivation

and is concentrated at the transition between redbeds and of transverse basement structures in early Paleozoic (Fig. 3;

carbonates. The source of metal is inferred to be the volca- Cecile et al., 1997). In northern British Columbia, the plat-

nic-rich sedimentary rocks of the basal Coates Lake Group form-to-basin transition resumes its southeasterly trend and

(Jefferson and Ruelle, 1986). Overlying glaciogenic strata of lower Paleozoic deep-water facies were deposited in the nar-

the Rapitan Group (diamictite, mudstone) are host to one of row Kechika trough (Fig. 8). In southern Yukon and northern

the largest and most unusual undeveloped iron deposits in British Columbia, lower Paleozoic strata of Selwyn basin and

North America: the >5-billion-tonne Crest deposit (Figs. 5, Kechika trough are bounded to the west by the relatively high

7, 8; Yeo, 1986). The Rapitan banded iron formation consist standing McEvoy and Cassiar platforms that were probably

of hematite-jasper rhythmites, locally with dropstones, that contiguous prior to Eocene displacement on the Tintina fault

are interpreted to be chemical precipitates formed during a (Figs. 7b, 8). This belt of outboard platformal facies is inferred

major marine transgression in the aftermath of the Sturtian to indicate the presence of thicker, less extended continental

snowball event (Hoffman and Schrag, 2002). Accordingly, crust that attests to the heterogeneous style of extension that

iron was dissolved in anoxic seawater that existed in an ice- occurred along the early Paleozoic continental margin.

covered silled basin (Baldwin et al., 2012), and the iron for- Similar basement highs are also inferred from well-doc-

mation was deposited at the end of glaciation by the oxidation umented thickness and facies variations in lower Paleozoic

of ferrous iron when ocean and atmosphere once again outer continental margin strata of the western Rocky and

interacted. Purcell Mountains in southeastern British Columbia (Fig. 7c;

Fig. 7. Schematic stratigraphic relationships for Neoproterozoic and younger strata of the Ancestral North American

margin. (a) north-south section across Ogilvie platform (Yukon stable block) and northern Selwyn basin in Yukon. (b) east-

west section across Mackenzie platform and Selwyn basin in Northwest Territories and Yukon. (c) east-west section across

the southern Rockies and Selkirk Mountains at the latitude of the Trans-Canada highway in Alberta and British Columbia.

Approximate lines of sections are shown in Figure 8. Approximate stratigraphic positions of major mineral deposits hosted

in Neoproterozoic-Paleozoic strata are shown. Although epigenetic, the general stratigraphic position for Carlin-type gold

occurrences in Yukon is also shown for reference. Sections a and b are modified after Abbott (1997); horizontal datum is

the base of the Earn Group or Besa River Formation. Section a is modified to account for recent mapping by Colpron et al.

(2013). Section c is modified after Price et al. (1972) for the Rocky Mountains; horizontal datum is the transition from marine

to nonmarine Jurassic rocks, which corresponds approximately with the transition from continental margin to foreland basin

deposition. The western part of section c through the Dogtooth and Selkirk Mountains is inspired from Kubli and Simony

(1992) and Logan and Colpron (2006).

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

THE CORDILLERA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, YUKON, AND ALASKA: TECTONICS AND METALLOGENY 65

a) S

Selwyn basin Yukon stable block

N

(Wernecke Mtns)

=J Marg 7?ps

4T =J 4?MC

=G

=J - Jones Lake Fm 5S - Sombre Fm `S - Sekwi Fm 54E >g 54E Earn Group

4?MC - Mount Christie Fm 5C - Camsell Fm {`V - Vampire Fm 5O

4T - Tsichu Fm ^5D - Delorme Fm {`BR - Backbone Rgs Fm Road River ^5c

54BR - Besa River Fm ^5S - Sapper Fm {`I - Ingta Fm `G _^D ^v

{`HN `5B

54E - Earn Gp ^S - Steele Fm {`HN - Narchilla Fm {HA

a _^c

54P - Prevost Fm _^W - Whittaker Fm {HA - Algae Fm

>g

Osiris-Conrad

5PL - Portrait Lake Fm `5B - Bouvette Fm {HY - Yusezu Fm `SC

5O - Ogilvie Fm `^H - Haywire Fm {B - Blueflower Fm {`I

5F - Funeral Fm _BS - Broken Skull Fm {SH - Sheepbed Fm {B H

5GB - Grizzly Bear Fm _^D - Duo Lakes Fm {IB - Icebrook Fm {S

r

5N - Nahanni Fm `_R - Rabbitkettle Fm {K - Keele Fm Hyland {HY pe {T

up {SZ

5H - Headless Fm `SC - Slats Creek Fm {T - Twitya Fm Group

t

faul

5L - `A - Avalanche Fm {SZ - Shezal Fm {SA

Landry Fm Paleo- and Mesoproterozoic

Ck

5NA - Natla Fm `RS - Rockslide Fm {SA - Sayunei Fm "basement"

Crest

Hay

s on

itan

5A - Arnica Fm `G - Gull Lake Fm {CL - Coates Lake Gp (Wernecke Supergroup,

W

Unnamed units have lower case identifiers Hart River basalt, Pinguicula Gp

Rap

ind

Daw

Hematite Creek Gp)

erm

ere

b) W =J E

Selwyn basin 4?MC Mackenzie platform

4T

Earn Group 54Ep

Mac Pass

5Ep 54BR

5F,5GB

^S

Howards Pass

Road River Group 5L,5H,5N

^5c _^D ^5S

`^H

Anvil `_R

l`V

`A

`G `_BS 5S,5C,5A,5NA

{HA

Ha

{`HN

L i mi t of `_R Prairie Ck ^5D,

_^W

McEvoy e

x

p

`RS

Coates Lk

o `S {CL

Hyland s

u

Group r e

{HY

lower Neoproterozoic

"basement"

{K

Gp {SA

BR

(Mackenzie Mountains spgp)

{`

Mineral Occurrences

H

{S

pi {SZ

3000

Carlin-type Au (epigenetic)

n

Backbone

ta

VMS

{T

{IB

Ranges Fm

Ra

SEDEX - Irish Windermere

Supergroup

MVT “upper Windermere”

Rapitan iron Hay Creek Gp

Sed.-hosted Cu 0m

c) Selkirk Purcell Rocky Mountains

Calgary

W E

Mountains Mountains

Banff

U3-( Paskap

oo Fm

Cypru

s Hills

Rocky Mtn

Field, BC

L3 Brazeau Fm Edmonton

trench

Bl Fm

air

M-U< - L3 m

or Belly River Fm

Koo eG

tena p Alberta Gp

y

L< Fernie

=

@-? Fairholme Gp

Rogers

Rundle Gp

Pass

E{-0

Revelstoke

ent

54 Banff Fm basem

Palliser Fm

Sassenach Fm

sub-Devonian unconformity

e

Beaverfoot llin Calcareous sandstone,

sta

U_-L^ Mt Wilson siltstone and shale

y

Broadview Glenogle cr Chert conglomerate, grit

c

p sandstone, and siltstone

M`

U`-M_

ay G

Lardeau Group

54g

McK

Jowett Fm Chert, shale

Akolkole Shale

Ice River

x Fm complex

Dogtooth Siltstone, shale

high

Chancellor Fm

Sandstone, siltstone, shale

n

Index Fm M`

entia

Goldstream >g Shale, sandstone

Badshot

Laur

Grit, sandstone, shale

J&L (turbidites)

p

Hamil

G

l Gp Diamictite

Gp

og

Syenite

Hors

G

te

U{-L` ethie Quartzite

iet

Grouf Cree Granodiorite

Hor

M

seth

ie

p k Silty and argillaceous

Gro f Cree Diabase sills and dikes limestone

up k U{

Felsic volcanic rocks Dolostone

U{ M{ Purcell Spgp

Mafic volcanic rocks Limestone

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

66 NELSON ET AL.

124°W

116°W

108°

°W

132°W

°W

140°W

156

148

W

Arctic Lower Paleozoic

Ocean volcanic occurrences

Pericratonic terranes 70°N

with western Laurentian ancestry

Ancestral North America

deep-water facies

Richardson

trough Ancestral North America

continental platform

a

Yukon

Alask

Yukon

Stable

block

NWT

66°N

Dawson

fault A Crest

Goz Mackenzie

platform

easte

Selwyn

basin

rn

Coates Lk

Howards B 62°N

Anvil Pass

Cassiar/

McEvoy

limit

platforms

Yukon NWT

BC

Alberta

MacDonald

of 58°N

platform

Pacific

Ocean Kechika

Al trough

Co

as

ka

rd

ille

ran

Rapitan-type iron

54°N

Sediment-hosted Cu

def

MVT deposit orm

atio

n

VMS, SEDEX deposit

“Kootenay arc type” Kootenay

carbonate-hosted deep-water Goldstream C

stratiform/replacement facies

deposit

50°N

Kootenay BC

0 100 200 300 arc deposits USA

116°W

km

Fig. 8. Distribution of late Neoproterozoic and early Paleozoic deposits and paleogeographic elements of the Ancestral

North American margin. Lower Paleozoic volcanic occurrences are from Goodfellow et al. (1995). Deposit locations from

J.G. Abbott et al. (1986), Nelson (1991), Logan and Colpron (2006), Massey (2000a,b). Red lines show approximate line of

stratigraphic sections in Figure 7.

e.g., Windermere and Dogtooth highs of Reesor, 1973; and does not correspond to coeval shallow-water units of the conti-

Kubli and Simony, 1992, respectively). To the west, in the nental shelf to the east. The Lardeau Group is thought to rep-

Selkirk Mountains, thick Lower Cambrian limestone of the resent deposition in a deep trough along the outer continent

Badshot Formation occurs near the base of the Kootenay ter- margin (Fig. 7c; Logan and Colpron, 2006), a southern equiv-

rane, which comprises the most westerly exposure of parau- alent of the Selwyn basin and Kechika trough. This succession

tochthonous lower Paleozoic strata (Colpron and Price, 1995). extends southward into northeastern Washington State along

The Badshot Limestone is overlain by the Lardeau Group, a the curvilinear Kootenay arc (Fig. 8). The southern, SW-strik-

>3.5-km-thick lower Paleozoic succession of graphitic phyl- ing flank of the Kootenay arc marks another westward shift of

lite, immature siliciclastic rocks, and mafic volcanic rocks that nearly 100 km in the platform to basin transition that has been

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/books/chapter-pdf/3811598/9781629491639_ch03.pdf

by guest

THE CORDILLERA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, YUKON, AND ALASKA: TECTONICS AND METALLOGENY 67

ascribed to reactivation of basement faults that are generally in pyrite, low sedimentation rates, and the absence of local

aligned with the Vulcan structure in the Alberta basement to scarp-related facies or volcanic activity.

the east (Fig. 3; Price, 1981). Mafic volcanic rocks of MORB

to ocean island basalt (OIB: enriched intraplate basalt) affinity The Peri-Laurentian Realm

occur at various stratigraphic horizons in the Lardeau Group,

but the two most widespread episodes (upper Index and Devonian-Mississippian arc construction, rifting,

Jowett formations; Fig. 7c) preceded influx of coarse clastic and drifting

rocks of the Akolkolex and Broadview formations (Logan and The Devonian marked a profound shift from extensional

Colpron, 2006). Coarse clastic rocks in the Lardeau Group are processes related to continental breakup and its long after-

inferred to be sourced in Neoproterozoic strata of the Hors- math, to subduction-related processes. After breakup of

ethief Creek and Hamill groups exhumed along the basement Ancestral North America in the Neoproterozoic, rifting

highs in the Purcell Mountains. processes continued on the continental margin for another

In contrast to the Neoproterozoic, numerous syngenetic 150 m.y. During this interval, the continental margin occu-

deposits of Cambrian age occur in continental margin strata pied a single plate joined to oceanic lithosphere. Initiation of

of both the northern and southern Canadian Cordillera. The eastward subduction of oceanic crust beneath the continent

Faro deposits in Yukon, which were mined for nearly 30 years in the Middle to Late Devonian led to inception of magmatic

(1970–1998), are part of the Anvil district, a NW-trending belt arcs along the length of the North American Cordillera, both

of SEDEX Zn-Pb-Ag deposits hosted in Cambrian siliceous in the autochthonous outer continental margin and in what

graphitic units in the uppermost part of the Mt. Mye Forma- would become the terranes of the peri-Laurentian realm

tion and lowermost Vangorda Formation in the western Sel- (Rubin et al., 1990; Colpron et al., 2006). Arc initiation fol-

wyn basin (equivalents to the Rabbitkettle Formation, Figs. lowed the closing of the Iapetus Ocean on the eastern flank

7b, 8; Jennings and Jilson, 1986; Pigage, 2004). The deposits of Ancestral North America, which caused a global shift in

are localized near the northeastern margin of the graphitic plate configurations and probably triggered subduction along

facies, an alignment that Jennings and Jilson (1986) related to its western edge.

a second-order extensional basin. Redox changes caused by The onset of arc magmatism is recorded within the conti-

the mixing of anoxic bottom waters were probably important nental margin and in the parautochthonous Kootenay terrane

within it (Shanks et al., 1987). and Yukon-Tanana upland, as well as in the Yukon-Tanana,

In the Kootenay arc of southern British Columbia, the Stikine, and Quesnel terranes (Fig. 9; Nelson et al., 2006;

Lower Cambrian Badshot Limestone is host to a number of Paradis et al., 2006a). Uranium-lead zircon crystallization

stratiform, strata-bound, laminated to massive sulfide bod- ages range from ca. 390 to 320 Ma, with the major peak at

ies (Fig. 8; Nelson, 1991). They have many features in com- 360 to 350 Ma (Nelson et al., 2006). Throughout this interval,

mon with Irish-type deposits and, like them, probably arose magmatism was markedly bimodal. Felsic components show

through fluid venting along sea-floor growth faults. The pres- significant contributions of continental crust. Mafic compo-

ence of carbonate led to more extensive subsurface replace- nents show diverse geochemical signatures including the fol-

ment mineralization than in typical SEDEX deposits. lowing: arc tholeiite, calc-alkalic, MORB, E-MORB (enriched