Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Definition of "betrayal of public trust

Uploaded by

Kalteng Fajardo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

65 views12 pagesOriginal Title

21-05-29 Not All Violations of the Constitution are Culpable

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

65 views12 pagesDefinition of "betrayal of public trust

Uploaded by

Kalteng FajardoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

For purposes of impeachment, “culpable violation of the constitution”

is defined as “the deliberate and wrongful breach of the

Constitution.” Furthermore, “Violation of the Constitution made

unintentionally, in good faith, and mere mistakes in the proper

construction of the Constitution do not constitute and impeachable

offense.”

During the impeachment of then Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato

Corona, it was held that failure to disclose some bank accounts in his

SALN constituted culpable violation of the constitution.

On the other hand, In Francisco Jr. vs. Nagmamalasakit na mga

Manananggol ng mga Manggagawang Pilipino, Inc., the Supreme

Court purposely refused to define the meaning of “other high crimes

or betrayal of public trust,” saying that it is “a non-justiciable political

question which is beyond the scope of its judicial power.” However,

the Court refuses to name which agency can define it; the Court

impliedly gives the power to the House of Representatives, which

initiates all cases of impeachment.

This was further elucidated in Gutierrez v House of Representatives

Committee on Justice, G.R. No. 193495, February 15, 2011. Citing

the Constitutional deliberations, the Court said,

In Francisco, the Court noted that the framers of

the Constitution could find no better way to approximate

the boundaries of betrayal of public trust than by alluding

to positive and negative examples.9 Thus:

THE PRESIDENT. Commissioner Regalado is

recognized.

MR. REGALADO. Thank you, Madam President.

I have a series of questions here, some for

clarifications, some for the cogitative and reading

pleasure of the members of the Committee over a happy

weekend without prejudice later to proposing

amendments at the proper stage.

First, this is with respect to Section 2, on the

grounds for impeachment , and I quote:

. . . culpable violation of the Constitution, treason,

bribery, other high crimes, graft and corruption or

betrayal of public trust.

Just for the record, what would the Committee

envision as a betrayal of public trust which is not

otherwise covered by by other terms antecedent thereto?

MR. ROMULO. I think, if I may speak for the

Committee and subject to further comments of

Commissioner de los Reyes, the concept is that this is a

catchall phrase. Really, it refers to his oath of office, in

the end that the idea of public trust is connected with the

oath of office of the officer, and if he violates that oath of

office, then he has betrayed the trust.

MR. REGALADO. Thank you.

MR. MONSOD. Madam President, may I ask

Commissioner de los Reyes to perhaps add to those

remarks.

THE PRESIDENT. Commissioner de los Reyes is

recognized.

MR. DE LOS REYES. The reason I proposed this

amendment is that during the Regular Batasang

Pambansa where there was a move to impeach then

President Marcos, there were arguments to the effect that

there is no ground for impeachment because there is no

proof that President Marcos committed criminal acts

which are punishable, or considered penal offenses. And

so the term "betrayal of public trust," as explained

by Commissioner Romulo, is a catchall phrase to

include all acts which are not punishable by

statutes as penal offenses but, nonetheless, render

the officer unfit to continue in office. It includes

betrayal of public interest, inexcusable negligence

of duty, tyrannical abuse of power, breach of

official duty by malfeasance or misfeasance,

cronyism, favoritism, etc. to the prejudice of public

interest and which tend to bring the office into

disrepute. That is the purpose, Madam President.

Thank you.

MR. ROMULO. If I may add another example,

because Commissioner Regalado asked a very good

question. This concept would include, I think, obstruction

of justice since in his oath he swears to do justice to

every man; so if he does anything that obstructs justice,

it could be construed as a betrayal of public trust.

Thank you.

MR. NOLLEDO. In pursuing that statement of

Commissioner Romulo, Madam President, we will notice

that in the presidential oath of then President Marcos, he

stated that he will do justice to every man. If he appoints

a Minister of Justice and orders him to issue or to prepare

repressive decrees denying justice to a common man

without the President being held liable, I think this act will

not fall near the category of treason, nor will it fall under

bribery of other high crimes, neither will it fall under graft

and corruption. And so when the President tolerates

violations of human rights through the repressive decrees

authored by his Minister of Justice, the President betrays

the public trust.10

Clearly, the framers of the Constitution recognized

that an impeachment proceeding covers non-criminal

offenses. They included betrayal of public trust as a

catchall provision to cover non-criminal acts. The

framers of the Constitution intended to leave it to

the members of the House of Representatives to

determine what would constitute betrayal of

public trust as a ground for impeachment.

In Gonzales v Office of the President, G.R. No. 196231, September

4, 2012, the Court ruled:

The invariable rule is that administrative decisions

in matters within the executive jurisdiction can only be

set aside on proof of gross abuse of discretion, fraud, or

error of law.64 In the instant case, while the evidence may

show some amount of wrongdoing on the part of

petitioner, the Court seriously doubts the correctness of

the OP's conclusion that the imputed acts amount to

gross neglect of duty and grave misconduct constitutive

of betrayal of public trust. To say that petitioner's

offenses, as they factually appear, weigh heavily enough

to constitute betrayal of public trust would be to ignore

the significance of the legislature's intent in prescribing

the removal of the Deputy Ombudsman or the Special

Prosecutor for causes that, theretofore, had been

reserved only for the most serious violations that justify

the removal by impeachment of the highest officials of

the land.

Would every negligent act or misconduct in the

performance of a Deputy Ombudsman's duties constitute

betrayal of public trust warranting immediate removal

from office? The question calls for a deeper,

circumspective look at the nature of the grounds for the

removal of a Deputy Ombudsman and a Special

Prosecutor vis-a-vis common administrative offenses.

Betrayal of public trust is a new ground for

impeachment under the 1987 Constitution added to the

existing grounds of culpable violation of the Constitution,

treason, bribery, graft and corruption and other high

crimes. While it was deemed broad enough to cover any

violation of the oath of office, 65 the impreciseness of its

definition also created apprehension that "such an

overarching standard may be too broad and may be

subject to abuse and arbitrary exercise by the

legislature."66 Indeed, the catch-all phrase betrayal of

public trust that referred to "all acts not punishable by

statutes as penal offenses but, nonetheless, render the

officer unfit to continue in office" 67 could be easily utilized

for every conceivable misconduct or negligence in office.

However, deliberating on some workable standard by

which the ground could be reasonably interpreted, the

Constitutional Commission recognized that human error

and good faith precluded an adverse conclusion.

MR. VILLACORTA: x x x One last matter with

respect to the use of the words "betrayal of public trust"

as embodying a ground for impeachment that has been

raised by the Honorable Regalado. I am not a lawyer so I

can anticipate the difficulties that a layman may

encounter in understanding this provision and also the

possible abuses that the legislature can commit in

interpreting this phrase. It is to be noted that this ground

was also suggested in the 1971 Constitutional

Convention. A review of the Journals of that Convention

will show that it was not included; it was construed as

encompassing acts which are just short of being criminal

but constitute gross faithlessness against public trust,

tyrannical abuse of power, inexcusable negligence of

duty, favoritism, and gross exercise of discretionary

powers. I understand from the earlier discussions that

these constitute violations of the oath of office, and also I

heard the Honorable Davide say that even the criminal

acts that were enumerated in the earlier 1973 provision

on this matter constitute betrayal of public trust as well.

In order to avoid confusion, would it not be clearer to

stick to the wording of Section 2 which reads: "may be

removed from office on impeachment for and conviction

of, culpable violation of the Constitution, treason, bribery,

and other high crimes, graft and corruption or

VIOLATION OF HIS OATH OF OFFICE", because if

betrayal of public trust encompasses the earlier acts that

were enumerated, then it would behoove us to be equally

clear about this last provision or phrase.

MR. NOLLEDO: x x x I think we will miss a golden

opportunity if we fail to adopt the words "betrayal of

public trust" in the 1986 Constitution. But I would like him

to know that we are amenable to any possible

amendment. Besides, I think plain error of judgment,

where circumstances may indicate that there is good

faith, to my mind, will not constitute betrayal of public

trust if that statement will allay the fears of difficulty in

interpreting the term."68 (Emphasis supplied)

The Constitutional Commission eventually found it

reasonably acceptable for the phrase betrayal of public

trust to refer to "acts which are just short of being

criminal but constitute gross faithlessness against public

trust, tyrannical abuse of power, inexcusable negligence

of duty, favoritism, and gross exercise of discretionary

powers."69 In other words, acts that should constitute

betrayal of public trust as to warrant removal from office

may be less than criminal but must be attended by bad

faith and of such gravity and seriousness as the other

grounds for impeachment.

A Deputy Ombudsman and a Special Prosecutor are

not impeachable officers. However, by providing for their

removal from office on the same grounds as removal by

impeachment, the legislature could not have intended to

redefine constitutional standards of culpable violation of

the Constitution, treason, bribery, graft and corruption,

other high crimes, as well as betrayal of public trust, and

apply them less stringently. Hence, where betrayal of

public trust, for purposes of impeachment, was not

intended to cover all kinds of official wrongdoing and

plain errors of judgment, this should remain true even for

purposes of removing a Deputy Ombudsman and Special

Prosecutor from office. Hence, the fact that the grounds

for impeachment have been made statutory grounds for

the removal by the President of a Deputy Ombudsman

and Special Prosecutor cannot diminish the seriousness of

their nature nor the acuity of their scope. Betrayal of

public trust could not suddenly "overreach" to cover acts

that are not vicious or malevolent on the same level as

the other grounds for impeachment.

In his opinion piece published December 8, 2017,

(https://manilastandard.net/opinion/253545/culpable-violation-of-

the-constitution.html) Fr. Ranhilio Aquino gave his opinion on the

issue of culpable violation of the Constitution,

In respect to the duties of the highest officials of

the land towards the Constitution, the Constitutional

Court of South Africa ( Cases CCT 143/15 and CCT

171/15, March 31, 2016), in the case against President

Jacob Zuma, said of the President’s violation of the

Constitution: “This requires the President to do all he can

to ensure that our constitutional democracy thrives. He

must provide support to all institutions or measures

designed to strengthen our constitutional democracy.

More directly, he is to ensure that the Constitution is

known, treated and related to, as the supreme law of the

Republic. It thus ill-behooves him to act in a manner

inconsistent with what the Constitution requires him to do

under all circumstances.” From this South African

precedent, we are taught that acts or omissions that

undermine constitutional institutions and that run

roughshod over the workings of a democracy constitute

culpable violations of the constitution.

Thus far, all references have been to the

impeachment of a president. Should the grounds be

construed differently when the officer at the bar is the

Chief Justice (or perhaps the chair of any of the

independent Constitutional Commissions)? Although quite

clearly, the way a Chief Justice will culpably violate the

constitution is different from the way a President will be

guilty of the same charge by virtue of the differences in

the nature of their offices, the Philippine Constitution

textually provides for the same grounds. Where the law

does not distinguish, distinctions subsequently introduced

are spurious!

What “culpable violation of the Constitution” can

further mean may very well be suggested by American

precedent. A thorough study by Jared Cole and Todd

Garvey of the US Congressional Research Service

(October, 2015) entitled “Impeachment and Removal”

includes a summary of different impeachment cases. In

1868, Andrew Jackson, the US President, was impeached

for violating the Tenure of Office Act and likewise for

haranguing Congress and for questioning legislative

authority. Nixon’s case in 1974 had to do with the

supposed misuse of the powers of his office to obstruct

investigation of the Watergate Hotel break-in. Then there

was the well-publicized and televised trial of President Bill

Clinton for behavior considered incompatible with the

nature of the office of the Presidency. The terms of

indictment should be instructive: “William Jefferson

Clinton has undermined the integrity of his office, has

brought disrepute on the Presidency, has betrayed his

trust as President and has acted in a manner subversive

of the Rule of Law and justice, to the manifest injury of

the people of the United States.” It is the Constitution

that lays down the powers of the Chief Justice and

whether or not her conduct as undermined the integrity

of her office or brought it in disrepute or whether her acts

or omissions have subverted the rule of law and justice all

constitute the question of whether or not she culpably

violated the Constitution.

But it is against federal judges that the

impeachment mechanism has been more frequently used.

Judge Harry Claiborne (1986) was impeached and

convicted for providing false information on federal

income tax forms, for having brought the judiciary into

disrepute by his conviction in a criminal case for perjury.

In relation to his case, it was said that while it was

devastating to the judiciary for judges to be perceived as

dishonest, it was as devastating for the entire

government for a President to perjure. And the

misbehavior need not be in the regard to the

performance of official duties. Judge Thomas Porteus

(2010) was impeached for misconduct committed prior to

his appointment to his present position—leaving no doubt

that actions prior to appointment may return to haunt the

respondent in impeachment proceedings.

While some earlier cases are disturbing in that

impeachment and removal from office after conviction

seem disproportional to the offense, the relative ease

with which judges are impeached and convicted is

explained by the fact that in the United States, the only

way federal judges can be removed from office is by

impeachment.

In respect to the “political justice” that

impeachment and trial mediate, Alexander Hamilton in

Federalist Papers No. 65 has a clear explanation: “…those

offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public

men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of

some public trust. They are of a nature which may with

peculiar propriety be denominated ‘political’ as they relate

chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”

As to “culpable”, the point should be clear: One is

punished for wrong deliberately perpetrated, but one

cannot be punished for a mistake or for an opinion. If one

in high office should maintain an opinion that should later

prove to be wrong, disastrous even—as a mistaken

command or maneuver during war, there certainly would

be error, and if error is so frequent and so egregious, it

may indicate incompetence, but that would not be the

“culpable violation” that is required for impeachment.

Rather a deliberate violation of the prescriptions and

precepts, the ordering and the principles, the premises

and the entailments of the constitutional order—this

would be actionable and a ground to evict the perpetrator

from high office.

This understanding of the mechanism of

impeachment and trial coupled with what American,

Korean and South African precedents tell us about high

office and obligations towards the constitution leave us

with the conclusion that while “culpable violation of the

constitution” may not be susceptible of the parsing into

elements that is characteristic of common crimes, it is

neither a vacuous term and one that has to do with the

very nature of high office in the workings of a

constitutional democracy and in the support of its

institutions and vigilance over its fundamental principles.

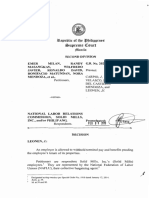

In his dissenting opinion in the case of Republic v Sereno, Justice

Carpio forwarded the following opinion:

In Casimiro v. Rigor, 13 the Court stated that the

filing of SALN promotes transparency in the civil service

and serves as an effective mechanism to verify

undisclosed wealth, thus:

The requirement of filing a SALN is enshrined in the

Constitution to promote transparency in the civil service

and serves as a deterrent against government officials

bent on enriching themselves through unlawful means. By

mandate of law, every government official or employee

must make a complete disclosure of his assets, liabilities

and net worth in order to avoid any issue regarding

questionable accumulation of wealth. The importance of

requiring the submission of a complete, truthful, and

sworn SALN as a measure to defeat corruption in the

bureaucracy cannot be gainsaid. Full disclosure of wealth

in the SALN is necessary to particularly minimize, if not

altogether eradicate, the opportunities for official

corruption, and maintain a standard of honesty in the

public service. Through the SALN, the public can monitor

movement in the fortune of a public official; it serves as a

valid check and balance mechanism to verify undisclosed

properties and wealth. The failure to file a truthful SALN

reasonably puts in doubt the integrity of the officer and

normally amounts to dishonesty.

Considering that the requirement of filing a SALN

within the period prescribed by law is enshrined in the

Constitution, the non-filing of SALN within the prescribed

period clearly constitutes a violation of an express

constitutional mandate. The repeated non-filing of

SALN therefore constitutes culpable violation of

the Constitution and betrayal of public trust, which

are grounds for impeachment under the

Constitution.

Culpable violation of the Constitution must be

understood to mean "willful and intentional violation of

the Constitution and not violations committed

unintentionally or involuntarily or in good faith or through

an honest mistake of judgment." 14 The framers of the

Constitution, particularly the Committee on Accountability

of Public Officers, "accepted the view that [culpable

violation of the Constitution] implied 'deliberate intent,

perhaps even a certain degree of perversity for it is not

easy to imagine that individuals in the category of these

officials would go so far as to defy knowingly what the

Constitution commands."' 15

Betrayal of public trust, on the other hand, refers to

acts "less than criminal but must be attended by bad faith

and of such gravity and seriousness as the other grounds

for impeachment," as the Court held m Gonzales III v.

Office of the President of the Philippines, 16 thus:

Betrayal of public trust is a new ground for

impeachment under the 1987 Constitution added to the

existing grounds of culpable violation of the Constitution,

treason, bribery, graft and corruption and other high

crimes. While it was deemed broad enough to cover any

violation of the oath of office, the impreciseness of its

definition also created apprehension that "such an

overarching standard may be too broad and may be

subject to abuse and arbitrary exercise by the

legislature." Indeed, the catch-all phrase betrayal of

public trust that referred to "all acts not punishable by

statutes as penal offenses but, nonetheless, render the

officer unfit to continue in office" could be easily utilized

for every conceivable misconduct or negligence in office.

However, deliberating on some workable standard by

which the ground could be reasonably interpreted, the

Constitutional Commission recognized that human error

and good faith precluded an adverse conclusion.

xxxx

The Constitutional Commission eventually found it

reasonably acceptable for the phrase betrayal of public

trust to refer to "acts which are just short of being

criminal but constitute gross faithlessness against public

trust, tyrannical abuse of power, inexcusable negligence

of duty, favoritism, and gross exercise of discretionary

powers." In other words, acts that should

constitute betrayal of public trust as to warrant

removal from office may be less than criminal but

must be attended by bad faith and of such gravity

and seriousness as the other grounds for

impeachment. (Emphasis supplied)

Since the repeated failure to file the SALN

constitutes culpable violation of the Constitution and

betrayal of public trust, it is immaterial if the failure to file

the SALN is committed before appointment to an

impeachable office. However, it is up to Congress, which

is the constitutional body vested with the exclusive

authority to remove impeachable officers, to determine if

the culpable violation of the Constitution or betrayal of

public trust, committed before appointment as an

impeachable officer, warrants removal from office

considering the need to maintain public trust in public

office. For instance, if an impeachable officer is

discovered to have committed treason before his

appointment, it is up to the impeachment court to

determine if the continuance in office of the impeachable

officer is detrimental to national security warranting

removal from office.

It might be important to note that impeachment is only a mode of

removing an impeachable officer from office, and is not meant as a

punishment as explained by the Court in A.M. No. 20-07-10-SC,

January 12, 2021, Re: Letter of Mrs. Ma. Christina Roco Corona

Requesting the Grant of Retirement and Other Benefits, thus:

The object of the process is not to punish but only

to remove a person from office. As Justice Storey put it in

his commentary on the Constitution, impeachment is "a

proceeding, purely of a political nature, is not so much

designed to punish an offender as to secure the state

against gross political misdemeanors. It touches neither

his person nor his property, but simply divests him of his

political capacity." Put differently, removal and

disqualification are the only punishments that can be

imposed upon conviction on impeachment. Criminal and

civil liability can follow after the officer has been removed

by impeachment. Prosecution after impeachment does

not constitute prohibited double jeopardy.21 (Emphasis

supplied)

Impeachment is, thus, designed to remove the

impeachable officer from office, not punish him.22 It is

purely political, and it is neither civil, criminal, nor

administrative in nature. No legally actionable liability

attaches to the public officer by a mere judgment of

impeachment against him or her, and thus lies the

necessity for a separate conviction for charges that must

be properly filed with courts of law.

The nature and effect of impeachment proceedings

is so limiting that forum shopping or alleged violation of

the right against double jeopardy could not even be

successfully invoked upon the institution of the separate

complaints or Information.

In a number of cases, including the case that ousted former CJ

Sereno, failure to file SALN’s were considered culpable violation of

the Constitution.

You might also like

- Foundling CitizenshipDocument2 pagesFoundling CitizenshipJackie CanlasNo ratings yet

- SPS. CARLOS S. ROMUALDEZ AND ERLINDA R. ROMUALDEZ, Petitioners, v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS AND DENNIS GARAY, Respondents.Document16 pagesSPS. CARLOS S. ROMUALDEZ AND ERLINDA R. ROMUALDEZ, Petitioners, v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS AND DENNIS GARAY, Respondents.ZACH MATTHEW GALENDEZNo ratings yet

- (D1) Pan American World Airways, Inc. V. RapadasDocument2 pages(D1) Pan American World Airways, Inc. V. RapadasMhaliNo ratings yet

- The Payment of Bonus Act1965Document9 pagesThe Payment of Bonus Act1965nishi18guptaNo ratings yet

- G R - No - 213972Document5 pagesG R - No - 213972hsjhsNo ratings yet

- Malcaba V ProhealthDocument17 pagesMalcaba V ProhealthJanelle Leano MarianoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law DLSu Part (1) - 21-30Document10 pagesCriminal Law DLSu Part (1) - 21-30Jose Jarlath0% (1)

- Law On Accountability of Public Officer - COMPLETEDocument396 pagesLaw On Accountability of Public Officer - COMPLETEColBenjaminAsiddaoNo ratings yet

- Alternative Dispute Resolution Act SummaryDocument15 pagesAlternative Dispute Resolution Act SummaryIrene RamiloNo ratings yet

- PNB vs. Sps. RocamoraDocument11 pagesPNB vs. Sps. Rocamorayan_saavedra_1No ratings yet

- 2016 Political Law and Public International Law - de CastroDocument45 pages2016 Political Law and Public International Law - de CastroJay AmorNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Provisions On TaxationDocument2 pagesConstitutional Provisions On TaxationPeter ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Reassessing The Anti Rape Law of 1997 and The Rape Victim Assistance and Protection Act of 1998Document9 pagesReassessing The Anti Rape Law of 1997 and The Rape Victim Assistance and Protection Act of 1998chaynagirlNo ratings yet

- Anti-Plunder Law and Bouncing Checks LawDocument19 pagesAnti-Plunder Law and Bouncing Checks LawjbandNo ratings yet

- TRAIN Act Salient FeaturesDocument17 pagesTRAIN Act Salient FeaturesPearl EniegoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document3 pagesChapter 1Mei XiaoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Circumstantial EvidenceDocument30 pagesCriminal Law Circumstantial EvidenceConcia Fhynn San Jose100% (1)

- Ewgwehgw 34 Uyh 423 Uy 423Document3 pagesEwgwehgw 34 Uyh 423 Uy 423ROA ARCHITECTSNo ratings yet

- Feb 8 Senate Impeachment Court RecordDocument79 pagesFeb 8 Senate Impeachment Court RecordVERA FilesNo ratings yet

- Writ of AmparoDocument6 pagesWrit of AmparoKria ManglapusNo ratings yet

- Property - Rights of Riparian Owners To Alluvion Formed As A ResuDocument5 pagesProperty - Rights of Riparian Owners To Alluvion Formed As A ResuPorsh RobrigadoNo ratings yet

- Philippines Treaty Provides Framework for Mutual Legal AssistanceDocument31 pagesPhilippines Treaty Provides Framework for Mutual Legal AssistanceAttyl LlawNo ratings yet

- International conventions and Sri Lankan laws protecting women's and children's rightsDocument2 pagesInternational conventions and Sri Lankan laws protecting women's and children's rightsAruna Jayamanjula0% (1)

- Schedule of Classes S.Y. 2nd Sem 2020-2021Document14 pagesSchedule of Classes S.Y. 2nd Sem 2020-2021UE LawNo ratings yet

- The Legality of ProstitutionDocument5 pagesThe Legality of ProstitutionChrissy ChenNo ratings yet

- INTERNATIONAL LAW ON TERRORISM - NEED TO REFORM by Sandhya P. KalamdhadDocument6 pagesINTERNATIONAL LAW ON TERRORISM - NEED TO REFORM by Sandhya P. KalamdhadDr. P.K. Pandey0% (1)

- CHAPTER 1 Other Definition of Terms and Application of Legal Medicine To LawDocument4 pagesCHAPTER 1 Other Definition of Terms and Application of Legal Medicine To LawIrish AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Facial ChallengeDocument3 pagesFacial ChallengecaramelsundaeNo ratings yet

- 6 Amending The Economic Provisions of The 1987 ConstitutionDocument48 pages6 Amending The Economic Provisions of The 1987 ConstitutionJonathan AguilarNo ratings yet

- Filipino Values SystemDocument35 pagesFilipino Values SystemGaVee Agran100% (1)

- Republic Act 11053 - New Anti Hazing LawDocument9 pagesRepublic Act 11053 - New Anti Hazing LawAnonymous WDEHEGxDhNo ratings yet

- Complementarity After Kampala: Capacity Building and The ICC's Legal ToolsDocument21 pagesComplementarity After Kampala: Capacity Building and The ICC's Legal ToolsariawilliamNo ratings yet

- Bangsamoro Basic Law - PresentationDocument20 pagesBangsamoro Basic Law - PresentationFatimah MandanganNo ratings yet

- Emergency Powers of The PresidentDocument2 pagesEmergency Powers of The PresidentSuhartoNo ratings yet

- Cases (Compilation)Document363 pagesCases (Compilation)AbbyNo ratings yet

- Plunder PresentationDocument35 pagesPlunder PresentationLoueljie Antigua100% (4)

- Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 and Rohingya Refugee CrisisDocument12 pagesCitizenship Amendment Act 2019 and Rohingya Refugee CrisisHumanyu KabeerNo ratings yet

- Persons and Family Relations Part OneDocument47 pagesPersons and Family Relations Part OneSpartansNo ratings yet

- Criminal Litigation 2017 Summary Part 1Document15 pagesCriminal Litigation 2017 Summary Part 1Angela MalesiNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL LAW TIPSDocument54 pagesCRIMINAL LAW TIPSPaula GasparNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations Article 234 240Document3 pagesLabor Relations Article 234 240Nikani Lhorelie RubiNo ratings yet

- Agency: Classification of Agents On The Basis of Authority On The Basis of Nature of WorkDocument8 pagesAgency: Classification of Agents On The Basis of Authority On The Basis of Nature of WorkATBNo ratings yet

- Motion To QuashDocument2 pagesMotion To QuashlmafNo ratings yet

- SC Abandons Condonation DoctrineDocument2 pagesSC Abandons Condonation DoctrineRalph Julius Leo MorcillaNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law Memoryaid: Code of CommerceDocument46 pagesCommercial Law Memoryaid: Code of CommerceCliffordNo ratings yet

- VVL Civil Law 2014Document30 pagesVVL Civil Law 2014prince lisingNo ratings yet

- Labor Law Review NOTES for Midterms 2015-2016Document15 pagesLabor Law Review NOTES for Midterms 2015-2016MichaelNo ratings yet

- Banking Laws PhilippinesDocument4 pagesBanking Laws PhilippinesIra Nathalie LunaNo ratings yet

- DOJ Memo On Tribal Pot PoliciesDocument3 pagesDOJ Memo On Tribal Pot Policiesstevennelson10100% (1)

- Tax 2 Finals (Remedies To Cta)Document27 pagesTax 2 Finals (Remedies To Cta)Athena SalasNo ratings yet

- AAAAACompiled Poli DigestDocument774 pagesAAAAACompiled Poli DigestVeah CaabayNo ratings yet

- Actions and Jurisdiction 2021Document16 pagesActions and Jurisdiction 2021reese93No ratings yet

- MIAA vs COADocument58 pagesMIAA vs COAJasper Kim ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Promoting E-Governance Through Right To InformationDocument9 pagesPromoting E-Governance Through Right To InformationIJSER ( ISSN 2229-5518 )No ratings yet

- Security Agency: 2/F, Sta. Ana Building, Fortich St. Malaybalay City, BukidnonDocument35 pagesSecurity Agency: 2/F, Sta. Ana Building, Fortich St. Malaybalay City, Bukidnonrapet_bisahan100% (1)

- Administrative Law MT ReviewerDocument3 pagesAdministrative Law MT ReviewerChey DumlaoNo ratings yet

- Finalized Impeachment Complaint v. Comm. Andres BautistaDocument24 pagesFinalized Impeachment Complaint v. Comm. Andres BautistaRapplerNo ratings yet

- Senator Pia Cayetano Decision ImpeachmentDocument2 pagesSenator Pia Cayetano Decision ImpeachmentSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Memorndum of Law DraftDocument7 pagesMemorndum of Law DraftGenevieve PenetranteNo ratings yet

- For ScribedDocument7 pagesFor ScribedKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-01-09 Legislative Grave Abuse of DiscretionDocument15 pages21-01-09 Legislative Grave Abuse of DiscretionKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-03-09 Comparative Provisions On Grant of Ownership of Industries To Filipino Citizens in The 1935, 1973, and 1987 ConstitutionDocument12 pages21-03-09 Comparative Provisions On Grant of Ownership of Industries To Filipino Citizens in The 1935, 1973, and 1987 ConstitutionKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 23-11-22 Motion To Release Cash Bond Ad CautelamDocument4 pages23-11-22 Motion To Release Cash Bond Ad CautelamKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 20-12-24 Oral Arguments Research Anti-Terror ActDocument66 pages20-12-24 Oral Arguments Research Anti-Terror ActKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- Comparative Current Periods of Detention Without Warrant or Judicial InterventionDocument29 pagesComparative Current Periods of Detention Without Warrant or Judicial InterventionKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-03-16 Exercise of Legislative Power by CongressDocument11 pages21-03-16 Exercise of Legislative Power by CongressKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-03-12 Supreme Court Cases Referencing Human Rights DefendersDocument33 pages21-03-12 Supreme Court Cases Referencing Human Rights DefendersKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-01-19 Congressional Grave Abuse of DiscretionDocument5 pages21-01-19 Congressional Grave Abuse of DiscretionKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- Deed of Sale: IN WITNESS WHEREOF, The Parties Hereto Have Signed This Deed This - Day ofDocument2 pagesDeed of Sale: IN WITNESS WHEREOF, The Parties Hereto Have Signed This Deed This - Day ofKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-01-16 Ex Post Facto Law and Bill of AttainderDocument14 pages21-01-16 Ex Post Facto Law and Bill of AttainderKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-01-21 Sale and Registration of Unregistered LandDocument4 pages21-01-21 Sale and Registration of Unregistered LandKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-04-15 Local Infrastructure and Public Works Devolved in Favor of Local Government UnitsDocument12 pages21-04-15 Local Infrastructure and Public Works Devolved in Favor of Local Government UnitsKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-04-25 Presidential Veto PowersDocument11 pages21-04-25 Presidential Veto PowersKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-03-16 Exercise of Legislative Power by CongressDocument11 pages21-03-16 Exercise of Legislative Power by CongressKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- Act. No 496 Land Registration Act ACT NO. 3344Document6 pagesAct. No 496 Land Registration Act ACT NO. 3344Kalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-05-20 Board Resolution Signatory RepresentativeDocument3 pages21-05-20 Board Resolution Signatory RepresentativeKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-04-25 Presidential Veto PowersDocument11 pages21-04-25 Presidential Veto PowersKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-05-20 Prescription and 24 Month RuleDocument18 pages21-05-20 Prescription and 24 Month RuleKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-05-07 Illegitimate ChildrenDocument2 pages21-05-07 Illegitimate ChildrenKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- 21-03-26 Congressional Power of The PurseDocument9 pages21-03-26 Congressional Power of The PurseKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- FAQs Anti Wiretapping LawDocument15 pagesFAQs Anti Wiretapping Lawjane_caraigNo ratings yet

- Are Foreign Nationals Entitled To The Same Constitutional Rights PDFDocument24 pagesAre Foreign Nationals Entitled To The Same Constitutional Rights PDFKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument17 pagesPDFKalteng FajardoNo ratings yet

- Sereno Dissent MLDocument51 pagesSereno Dissent MLJojo Malig100% (1)

- Supreme Court Rules on 2004-2007 Election Fraud CasesDocument58 pagesSupreme Court Rules on 2004-2007 Election Fraud CasesLiaa AquinoNo ratings yet

- Uprrme, ' - A:c I .L: !courtDocument13 pagesUprrme, ' - A:c I .L: !courtemersonbalgosNo ratings yet

- 1645Document4 pages1645Anonymous K286lBXothNo ratings yet

- 1645Document4 pages1645Anonymous K286lBXothNo ratings yet

- Sierra Leone-Lomé Peace Agreement Ratification Act (1999) (E)Document39 pagesSierra Leone-Lomé Peace Agreement Ratification Act (1999) (E)Shalom AlexNo ratings yet

- GIZ-Afghanistan: A. Position Applied ForDocument3 pagesGIZ-Afghanistan: A. Position Applied ForJaved ZakhilNo ratings yet

- Socioeconomic, Political and Security HazardsDocument17 pagesSocioeconomic, Political and Security HazardsJulianne CentenoNo ratings yet

- Software Project Management Risk ManagementDocument7 pagesSoftware Project Management Risk Managementsibhat mequanintNo ratings yet

- PARTY Room Agreement 2018 - TSCC 1689marisaDocument5 pagesPARTY Room Agreement 2018 - TSCC 1689marisaVasu PuriNo ratings yet

- MunicationDocument329 pagesMunicationdumitrubudaNo ratings yet

- ApEcon Module 8Document12 pagesApEcon Module 8Mary Ann PaladNo ratings yet

- Citystate Bank Held Liable for Negligence in Employee Fraud CaseDocument3 pagesCitystate Bank Held Liable for Negligence in Employee Fraud CaseMichael Vincent BautistaNo ratings yet

- Mulitilingual Education - Full PresentationDocument31 pagesMulitilingual Education - Full PresentationBlack BullsNo ratings yet

- National Cooperative Union of IndiaDocument148 pagesNational Cooperative Union of IndiaShweta AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Institute of Business Management: HRM-410 - Managing Human CapitalDocument12 pagesInstitute of Business Management: HRM-410 - Managing Human CapitalSmart JhnzbNo ratings yet

- Writing Process Worksheet (Accompanies Unit 9, Page 108) : NAME: - DATEDocument2 pagesWriting Process Worksheet (Accompanies Unit 9, Page 108) : NAME: - DATEJoan Suarez TomalaNo ratings yet

- Advance Listening - Group 13 - Tbi 2 Sem 3Document22 pagesAdvance Listening - Group 13 - Tbi 2 Sem 3jahadat kNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document13 pagesAssignment 1Muhammad Asim Hafeez ThindNo ratings yet

- TerminologyDocument6 pagesTerminologyDenílson100% (2)

- Accenture Thinking Strategically About The Interactive Advertising IndustryDocument13 pagesAccenture Thinking Strategically About The Interactive Advertising IndustrymscallonNo ratings yet

- Final Sip Lucky 12345Document42 pagesFinal Sip Lucky 12345Laxman bishtNo ratings yet

- Prescriptive vs. Descriptive GrammarDocument3 pagesPrescriptive vs. Descriptive GrammarRiza VergaraNo ratings yet

- Educational Measurement, Assessment and EvaluationDocument53 pagesEducational Measurement, Assessment and EvaluationBoyet Aluan100% (13)

- Educorp: International Conference On Recent Advances in Science Engineering and Technology (Icraset-2022)Document8 pagesEducorp: International Conference On Recent Advances in Science Engineering and Technology (Icraset-2022)Jeshifa G ImmanuelNo ratings yet

- Bonus: "Listen, I've Got A Spare Ten Minutes, I Was Just On My Way To Grab A Quick Coffee, Come and Join Me... "Document2 pagesBonus: "Listen, I've Got A Spare Ten Minutes, I Was Just On My Way To Grab A Quick Coffee, Come and Join Me... "asfdsdafsdafNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Core Values and Ethics of OD - AparreDocument20 pagesChapter 3 - Core Values and Ethics of OD - AparreMark Cherlit AparreNo ratings yet

- Kalyana C. Veluvolu Associate Professor ProfileDocument18 pagesKalyana C. Veluvolu Associate Professor ProfileSports CornerNo ratings yet

- YHT Realty Corporation V CADocument1 pageYHT Realty Corporation V CAJennifer OceñaNo ratings yet

- Gods Bits of Wood Chapter SummaryDocument3 pagesGods Bits of Wood Chapter SummaryStanley0% (1)

- Imaginary Product Report Road Runner Service ShopDocument36 pagesImaginary Product Report Road Runner Service ShopNotanNo ratings yet

- Alessia Fraser 1Document1 pageAlessia Fraser 1api-457791807No ratings yet

- AEOs JDs & KPIsDocument9 pagesAEOs JDs & KPIsRashid0% (1)

- Women's activewear trends and drivers reviewDocument27 pagesWomen's activewear trends and drivers reviewaqsa imranNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument5 pagesCase AnalysisArnav SharmaNo ratings yet