Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transpo Valencia From Kimwel

Uploaded by

Yollaine GaliasOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transpo Valencia From Kimwel

Uploaded by

Yollaine GaliasCopyright:

Available Formats

The Fraternal Order of St.

Thomas More

Transportation Law – Atty. Jocelyn A. Valencia

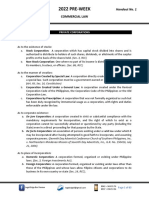

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part I

Chapter I. Common Carrier in General 1

Chapter II. Common Carrier of Goods 8

Chapter III. Common Carrier of Passengers 20

Chapter IV. Damages Recoverable from Common Carriers 29

Part II

Chapter I. Maritime and Admiralty Laws Code of Commerce 35

Chapter II. Charter Party 44

___________________________________________________________________________

―The King‘s Good Servant, But God‘s First‖

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 1

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

TRANSPORTATION LAW

PART I

CIVIL CODE PROVISIONS ON COMMON CARRIERS

CHAPTER I

COMMON CARRIERS IN GENERAL

LAWS GOVERNING CONTRACTS OF TRANSPORTATION BY LAND, SEA, OR AIR WITHIN THE

PHILIPPINES (1966 & 1969 BAR EXAMS)

1. Transportation by Land

A. Overland Transportation

a. Civil Code – primary law

b. Code of Commerce – suppletory law

B. Coomercial Transportation (object is merchandise)

a. Civil Code – primary law

b. Code of Commerce – suppletory law

2. Transportation by Sea

A. Coastwise

a. Civil Code – primary law

b. Code of Commerce – suppletory law

c. COGSA

Note: COGSA is not applicable even if the parties expressly provide for it.

B. Foreign Ports to Philippines Ports – The law of the Philippines still applies even if the

collision actually takes place in foreign waters.

a. Civil Code – primary law

b. Code of Commerce – suppletory law

c. COGSA

C. Philippine Ports to Foreign Ports – The laws of the country to which the goods are to

be transported (Eastern Shipping vs. IAC, 150 SCRA 463)

3. Air Transportation

A. Domestic – Civil Code

B. International – Warsaw Convention

C. Special laws also govern particular cases such as:

1. The Public Service Act;

2. The land Transportation and Traffic Code;

3. Tariff & Customs Code;

4. The Civil Aeronautics Act.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 2

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. TERMS CONNECTED WITH THE LAW ON TRANSPORTATION

Transportation is one whereby a certain person or association of persons obligate themselves to

transport persons, things, or news form one place to another for a fixed price.

KINDS OF TRANSPORTATION

A. According to its Object

1. things

2. persons

3. news

B. According to place of travel

1. Land

2. Water

a. Navigable canals

b. Lakes or rivers

c. Sea

3. Air

PARTIES TO A CONTRACT OF TRANSPORTATION

1. Shipper

2. Carrier or conductor

Transportation of Passengers

1. Shipper – who himself is the person to be transported

2. Carrier

Transportation of Things

1. Shipper

2. Carrier

3. Consigner

Transportation of News

1. Remitter

2. Carrier

3. Consignee

Shipper or consignor – One who gives rise to the contract of transportation by agreeing to deliver the

things or news to be transported, or to present his own person or those of other or others in the case of

the transportation of passengers

Carrier or conductor – One who binds himself to transport persons, things, or news as the case may

be, or one employed in or engaged in the business of carrying goods for others for hire. Carriers are

either common or private.

Consignee – The party to whom the carrier is to deliver the things to be transported or one to whom

the carrier may lawfully make delivery in accordance with its contract of carriage. The shipper and the

consignee may be merged in one person.

Freight – The term has been defined as:

1. The price or compensation paid for the transportation of goods by a carrier, at sea, from port to

port;

2. The hire paid for the carriage of goods on land from place to place, or inland streams or lakes;

3. The goods or merchandise transported at sea, on land or inland streams or lakes.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 3

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Private Carriers – Those who transport or undertake to transport in a particular instance for hire or

reward.

Common Carrier – One who holds itself out as ready to engage in the transportation of goods for hire

as a public employment and not as a casual occupation

DE GUZMAN V. CA

168 SCRA 612, December 22, 1988

Art. 1732 in defining common carrier carefully avoids making any distinction between a

person or enterprise offering transportation service on a regular or scheduled basis and one

offering such service on occasional, episodic or unscheduled basis. Neither does Art 1732

distinguish between a carrier offering its services to the general public, i.e., the general community

of population, and one who offers services or solicits business only from a narrow segment of the

general population. We think that Art 1732 deliberately refrained from making such distinctions.

Notwithstanding that a carrier has no certificate of public convenience, it is still a common

carrier. It is a palpable error to conclude that a person holds no certificate of public convenience is

not a common carrier. A certificate of public convenience is not a requisite for incurring a liability

under the Civil Code provisions governing common carriers. The liability arises the moment a

person or firm acts as a common carrier, without regard to whether or not such carrier has

complied with the requirements of the applicable regulatory statute and implementing regulations

and franchise. To exempt private respondent form liabilities of a common carrier because he has

not secured the necessary certificate of public convenience would be offensive to sound public

policy. That would be to reward private respondent precisely for failing to comply with applicable

statutory requirements.

TATAD vs. GARCIA, JR.

243 SCRA 436

In 1989, DOTC planned to construct a light railway transit line along EDSA. Only

private respondent EDSA LRT Consortium met the requirements and qualified for the financing

and implementation of the project.

Private Respondents shall undertake and finance the entire project required for a complete

operational light railway transit system. Upon full or partial completion and viability thereof,

shall operate the same. As agreed upon, private respondent‘s shall deliver the use and possession

of the competed portion to DOTC, which rentals to be paid by the DOTC on a monthly basis,

which basis, which, in turn shall come from the earnings of the EDSA LRT III.

Petitioners Senators Tatad, Orbos and Biazon as taxpayers questioned the constitutionality of

the agreement contending that based on Article XII Section II of the constitution, the ―operation

of a public utility‖ is limited to Filipinos or Filipino Corporations (60% of whose capital is owned

by Filipinos) and that private respondents is admitted a foreign corporation which cannot own and

operate the EDSA LRT III.

ISSUE: WON EDSA LRT Consortium (EDSA LRT Corp. LTD.) can own a public utility?

HELD: What private respondent owns are the rail tracks, rolling stocks power plant and not the

public utility. While a franchise is needed to operate these facilities, they do not by themselves

constitute public utility.

There is difference between ―operation of a public utility‖ and ―ownership of the facilities

and equipment‖ used to serve the public. Only the latter is what the PR exercises. Hence, PR can

own EDSA LRT II.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 4

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

General Rule: The Law Prohibits Unreasonable Discrimination by Common

Carriers

The law requires common carriers to carry for all persons, either passengers or property, for

exactly the same charge for a like or contemporaneous service in the transportation of like kind of

traffic under substantially similar circumstances or conditions. The law prohibits common carriers

from subjecting any person, etc., or locality, or any particular kind of traffic, to any undue or

unreasonable prejudice or discrimination whatsoever.

Exception: When the actual cost of handling and transporting the same is different.

The law did not intend to require common carriers to carry the same kind of merchandise,

even at the same price, under different and unlike conditions where the actual cost is different.

Determination of Justifiable Refusal

A common carrier may refuse to carry certain products which subject any persons, locality or

the traffic in such products to an unnecessary, undue, or unreasonable prejudice or discrimination

which involves a consideration of :

1. The sustainability of the vessels of the company for the transportation of such products;

1. The reasonable possibility of danger or disaster, resulting from their transportation in the form

and under the conditions in which they are offered for carriages;

2. The general nature of the business done by the carrier; and

3. All the attendant circumstances which might affect the question of reasonable necessity by the

carrier to undertake the transportation of this class of merchandise.

F.C FISHER vs. YANGCO STEAMSHIP COMPANY

31 PHIL 1

Plaintiff is stockholder in the Yangco Steamship Company, the owner of a large number of

steam vessels, duly licensed to engage in the coastwise trade of the Philippine Islands.

The directors of the company adopted a resolution which was thereafter ratified and

affirmed by the shareholders of the company, ―expressly declaring and providing that the classes of

merchandise to be carried by the company in its business as a common carrier do not include

dynamite, powder or other explosives, and expressly prohibiting the officers, agents and servants of

the company from offering to carry, accepting for carriage or carrying said dynamite, powder or

other explosives‖

Respondent Acting Collector of Customs demanded and required of the company the

acceptance and carriage of such explosives; that he has refused and suspended the issuance of the

necessary clearance documents of the vessels of the company unless and until the company

consents to accept such explosives for carriage;

Plaintiff is advised and believes that should the company decline to accept such explosives

for carriage, the respondent Attorney-General of the Philippine Islands and the respondent

prosecuting attorney of the city of Manila intend to institute proceedings under the penal provisions

of sections 4, 5,and 6 of Act No. 98 of the Philippine Commission against the company, its

mangers, agents and servants, to enforce the requirements of the Acting Collector of Customs as to

the acceptance of such explosives for carriage.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 5

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

ISSUES: 1. WON the refusal of the owners and officers of a steam vessel to accept for carriage

―dynamite, powder or other explosives‖ can be held to be a lawful act as to the conditions under

which such explosives are offered for carriage, or as to the suitableness of the vessel for the

transportation of such explosives?

2. Whether or not the possibility that the refusal to accept such articles of commerce in a particular

case may have the effect of subjecting any person or locality or the traffic in such explosives to an

undue, unreasonable or unnecessary prejudice or discrimination.

HELD: A refusal to carry explosives involves an unnecessary or reasonable preference or

advantage to any person, locality or particular kind of traffic or subjects any person, locality or

particular kind of traffic to an undue or unreasonable prejudice or discrimination is by no means

―self-evident‖, and that it is a question of fact to be determined by the particular circumstances

of each case.

Whatever may have been the rule at common law, common carriers in this jurisdiction

cannot lawfully decline to accept a particular class of goods for carriage to the prejudice of the

traffic in those goods unless it appears that for some sufficient reason the discrimination against the

traffic in such goods is reasonable and necessary. Mere prejudice or whim will not suffice. The

grounds of the discrimination must be substantial ones, such as will justify the courts in holding the

discrimination to have been reasonable and necessary under all the circumstances of the case.

It cannot be doubted that the refusal of a ―steamship company, the owner of a large number

of vessels‖ engaged in the coastwise trade of the Philippine Islands as a common carrier of

merchandise, to accept explosives for carriage on any of its vessels subjects the traffic in such

explosives to a manifest prejudice and discrimination, and in each case it is a question of fact

whether such prejudice or discrimination is undue, unnecessary or unreasonable.

PANTRANCO VS. PSC

70 PHIL. 221

The petitioner has been in the business of transportation passengers in the provinces of

Pangasinan and Tarlac by means of motor vehicles. Petitioner‘s application for authorization to

operate ten additional Brockway trucks was granted.However, he did not agree to the new

conditions imposed on the new certificate that the service can be required by the government upon

payment of the cost price less than depreciation, and, that the certificate shall be valid for a definite

period of time.

Petitioner assails the constitutionality of CA 454 authorizing the imposition of such condition

and prayed to declare the provisions thereof not applicable to valid and subsisting certificates issued

prior to June 8, 1939.

ISSUE: Whether or not it applies to valid and subsisting certificates. YES.

HELD: Under the 4th paragraph of section 15 of CA 146, the power of the PSC to prescribe the

conditions ―that the service can be acquired by the Commonwealth of the Phil. Or by the

instrumentality thereof upon payment of the cost price of its useful equipment, less reasonable

depreciation‖, and ―that the certificate shall be valid only for a definite period of time‖ is expressly

made applicable ―to any extension or amendment of certificates actually in force‖ and to

authorizations to renew and increase equipment and properties. Upon review these conditions were

purposely made applicable to existing certificates of public convenience.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 6

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

5. COMMON CARRIER DEFINITION & CHARACTERISTICS

DEFINITION

Art. 1732. Common carriers are persons, corporations, firms or associations engaged in the business of

carrying or transporting passengers or goods or both, by land, water, or air, for compensation, offering

their services to the public.

Art. 1733. Common carriers, from the nature of their business and for reasons of public policy, are bound

to observe extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods and for the safety of the passengers

transported by them, according to all the circumstances of each case.

Such extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods is further expressed in Articles 1734, 1735,

and 1745, Nos. 5, 6, and 7, while the extraordinary diligence for the safety of the passengers is further set

forth in Articles 1755 and 1756.

CHARACTERISTICS OF A COMMON CARRIER

In the case of Latimoso vs. Doliente CAR 769, the CA discussed the distinctive

characteristics of common carriers and emphasized that not all carriers qualify as and are subject to the

stringent responsibilities of common carriers also enumerated in the First Philippine Industrial Pipeline

v. CA 300 SCRA 661, which are:

1. He must be engaged in the business of carrying for others as a public employment, and

must hold himself out as ready to engage in the transportation of goods for persons

generally as a business, and not as casual occupation;

2. He must undertake to carry goods of the kind to which his business is confined;

3. He must undertake to carry by the methods by which business is conducted and over his

established roads and

4. the transportation must be for hire

DISTINCTIONS: COMMON CARRIER V. PRIVATE CARRIER

COMMON CARRIER PRIVATE CARRIER

1. Holds itself out to the public indiscriminately; 1. Contracts with particular individuals or groups only;

2. Extraordinary diligence is required; 2. Ordinary diligence is requires;

3. Subject to state regulations; 3. Not subject to state regulation;

4. Parties may not agree on limiting the carrier‘s 4. Parties may limit the carriers liability provide it is not

liability except when provided by law; contrary to law, morals, or good customs;

6. Exempting circumstances: 5. General exempting circumstance:

- Article 1733 of the New Civil Code: Prove - Article 1174 of the New Civil Code: Case Fortuito;

extraordinary diligence; and

- Article 1734 of the New Civil Code:

a. Flood, Storm. Earthquake, lightning,

or other natural disaster or calamity;

b. Act of the public enemy in war,

whether international or civil;

c. Act or omission of the shipper or

owner of goods;

d. The character of the goods or

defects in the packing or in the

containers;

e. Order or act of competent public

authority;

6. There is presumption of fault or negligence. 6. No presumption of fault or negligence.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 7

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANCE OF DISTINCTION

It is important to distinguish between common and private carriers because distinct and

different laws govern the rights and obligations of common and private carriers. The degree of

diligence set by law to be observed by common and private carriers in the carriage of goods or

passengers is not the same and the validity of the contracts and the stipulations therein are subject to

separate sets of public and legal restrictions.

CALTEX PHILS. INC vs. SULPICIO LINES

(G.R. No. 131166, September 30, 1999)

Charterer: Caltex

Ship: MT Vector

Owner of the Ship: Vector Shipping Corp.

Defendant: Sulpicio Lines

A motor tanker owned and operated by Vector Shipping Corp, engaged in the business of

transporting products such as gasoline, kerosse, diesel and crude oil. During a particular voyage it

carried fuel owned by Caltex by virtue of a charter contract between them, MV Doña is a passenger

and cargo vessel owned and operated by Sulpicio Lines, Inc is also plying the waters headed for

Manila. The two vessels collided in the open sea. All crew of Doña Paz died while 2 survived from

MT Vector. Out of the 4,000 passengers, only 24 survived from MV Doña Paz

The board of marine inquiry after an investigation found the MT Vector‘s registered operator,

Francisco Soriano and its owner and actual operator Vector Shipping Corp were responsible for its

collision with Doña Paz.

Teresita Canezal and her mother-in-law, widow and mother of a deceased due to the accident

filed a complaint for Damages arising from Breach of Contract of Carriage against Sulpicio Lines.

Sulpicio in the other hand filed a 3rd party complaint against Francisco Soriano, Vector Shipping

and Caltex alleging that Caltex chartered MT Vector with gross and evident bad faith despite its

being unseaworthy.

The trial court rendered a decision dismissing the third party complaint against the petitioner

favoring the complainants of the suit for damage. But on appeal to the CA interposed by Sulpicio,

the CA modified the TC‘s ruling and included petitioner as one of those liable for damages. Hence,

this petition.

ISSUE: Whether or not Caltex, the charterer of a sea vessel, is liable for damages resulting from a

collision between the chartered vessel and the passenger ship? NO.

HELD: The charterer has no liability for damages under the Philippine Maritime Laws. The

respective rights and duties of the shipper and the carrier depends not on whether the carrier is a

public or private carrier but on whether the contract of carriage is a bill of lading, or equivalent

shipping document on one hand or a chartered party or similar contract on the other . Petitioner and

Vector entered into a contract of affreightment also known as voyage charter.

Charter party – contract by which the entire ship or principal part is lent by the owner to another

person for a specified time or use.

Contract of Affreightment – is wherein the owner of the ship or other vessel lets the whole or part

of her to a merchant or other person for the conveyance of goods, on a particular voyage in

consideration of payment of freight. It leaves the general owner in possession of the ship as owner

of the voyage, the rights and responsibilities of ownership rest on the owner. The charterer is free

from liability to third persons in respect of the ship.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 8

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

The charterer of the vessel has no obligation before transporting its cargo to ensure that the

vessel it chartered complied with all legal requirements. The duty rests upon the common carrier for

being engaged in public service. The Civil Code demands diligence which is required by the nature

of the obligation between Caltex and MT Vector, liability found by CA is without basis.

The relationship between the parties in case is governed by special laws because of the

implied warranty of seaworthiness. Shippers of goods, when transacting with common carriers are

not expected to inquire upon the vessel‘s seaworthiness, genuineness of its licenses and compliance

with all maritime laws. To demand more form the shippers and hold them liable in case of failure

exhibits nothing but the futility of our maritime laws insofar as the protection of the public general

is concerned. Thus the nature of the obligation of Caltex demands ordinary diligence like any other

shipper in shipping his cargoes.

UNITED STATES vs. TAN PIACO

40 PHIL 853

Said defendants were charged with a violation of the Public Utility Law in that they were

operating utility without permission from the Public Utility Commissioner. The lower court found

Tan Piaco guilty of the crime charged.

Apparently, Tan Paico rented two automobile trucks and was using them upon the highways

of the Province of Leyte for the purpose of carrying some passengers and freight under a special

contract in each case. He had not held himself out to carry all passengers and all freight for all

persons who might offer passengers and freight.

ISSUE: WON the appellant was a public utility? NO.

HELD: As the Attorney-General said, the trucks furnished service under special agreement to carry

particular persons and property. These passengers, or the owners of the freight, may have controlled

the whole vehicle both as to content, direction and time of use. Which facts, under all circumstances

of the case would take away the defendants business from the provisions of the Public Utility Act.

Public Utility is hereby define to include individual, co partnership association corporation or

joint stock company, that nor or hereafter may own, operate, manage or control any common

carrier, railroad, street railway, engaged in the transportation of passengers, cargo for public use.

Public use means the same as use by the public. The essential feature of public use is that it is

not confined to privilege individuals, but is open to the indefinite public. There must be in general,

a right that the law compels the power to give the general public. It is not enough that the general

prosperity of the public is promoted. The true criterion by which to judge of the character of the use

is whether the public may enjoy it by right or only by permission.

UNITED STATES vs. QUINAJON

31 PHIL 189

Defendants Pascual Quinajon and Eugenio Quitoriano were charge violation of Act 98 of the

Civil Commission. It allege that the accused did willfully, unlawfully, and criminally demand and

collect from Provincial Treasurer, for the unloading of each one of the 5, 986 saks of rice, 10

centavos from it regular charge of 6 centavos.

ISSUE: WON defendants violated Act 98? YES.

HELD: Art. 98 of the Civil Commission in portion states that ―No common carrier shall xxx collect

or receive from any persons a greater or less compensation for any services rendered in the

transportation of passengers or property xxx under substantially similar conditions and

circumstances.‖

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 9

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

In this present case there is no pretense that it actually cost more to handle the rice for the

province than it did for the merchants with whom the special contracts were made. From the

evidence, it would seem that there was a clear discrimination is the thing, which is specifically

prohibited and punished under the law.

BASCOS v. CA

221 SCRA 318

Rodolfo Cipriano representing Cipriano Trading Enterprise entered into a hauling contract

with JBFAIR Shipping Agency Corp., whereby the former bound to haul the latter‘s 2,000 m/tons

of soya beans meal from Magallanes Drive, del Pan, Manila to the warehouse of Purefoods Corp.,

in Calamba Laguna. To carry out its obligation, CipTrade, through R Cipriano subcontracted

Estrellita Bascos to transport and to deliver 400 sacks of soya bean mea worth P156,404 from the

Manila Port Area to Calamba, Laguna at the rate of P50,000 per metric ton.

Petitioner failed to deliver the cargo. As a consequence Cipriano paid JIBFAIR for the

amount of lost goods in accordance with the contract they have agreed and that in cases of loss due

to theft, hijacking and of non-delivery or damages to the cargo CIPTRADE shall be held liable.

CIPRIANO demanded reimbursement from petitioner but the latter refused. So a complaint

was filed for a sum of money & damages with writ of preliminary attatchment for breach of

contract of carriage.

Petitioner interposes the ff defenses:

1. That there was no contract of carrage since CIPTRADE leased her cargo truck ;

2. That Ciptrade liable to the petitioner of P11 for loading the cargo;

3. That on the night of Oct. 21, 1988 the truck carrying the cargo was hijacked and that the

event was immediately reported to Ciptrade; petitioner and the police exerted all efforts to

locate the hijacked properties;

4. The hijacking being a force majeure, exculpated petitioner from any liability.

ISSUE: 1. WON petitioner is a common carrier? YES.

2. WON hijacking is a force majeure? NO.

HELD: Petitioner is a common carrier as defined in Art. 1732 of the Civil Code. The test to

determine a common carrier is to whether the given undertaking is part of the business engaged in

by the carrier which he has held out to the general public as his occupation rather than the quantity

or the extent of his business transacted. In this case, the petitioner herself has made the admission

that she was in trucking business, offering her trucks to those with cargo to move. Judicial

admissions are conclusive and no evidence is required to prove the same.

Hijacking does not constitute force majeure which will exculpate her from liability for the

loss of goods. To exculpate the carrier from liability arising from hijacking , he must prove that the

robbers and or the hijackers acted with grave or irresistible threat, violence or force in accordance

with Art. 1745 of the Civil Code. In the instant case, petitioner was not able to overcome the said

presumption. The accusatory affidavits which she presented were not enough to overcome the

same.

DE GUZMAN vs. CA

168 SCRA 612

Back-hauler of goods: Common carrier

Article 1732 makes no distinction between one whose principal business activity is the

carrying of persons or goods or both, and one who does such carrying only as an an cillary activity,

nor does it make distinctions between one who offers the service to the general public population.

Therefore, a party who ―back-hauled‖ goods for other merchants from Manila to Pangasinan, even

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 10

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

when such activity was only periodical or occasional and was not its principal line of business, or

that the rate it charges is below the commercial rate or toes not possess a CPC are subject to the

responsibilities and obligations of a common carrier an the lack of a CPC is not a requisite for

incurring liability under the Civil Code provisions on COMMON CARRIER.

FIRST PHILIPPINE PIPELINE CORP. VS, CA

300 SCRA 661

Pipeline Operator: Common carrier

A grantee of a pipeline concession applied for a Mayor‘s permit with the Office of the Mayor

of Batangas City. It was transporting petroleum products through its pipelines. However, before the

permit could be issued, the City Treasurer required FPIC to pay a local tax on its gross receipts for

1993. FPIC protested the payment of the tax and argued that it was a pipeline operator engaged in

business of transporting petroleum products from the Batangas refineries, and as such, exempted

from paying the gross receipt tax being a common carrier. The Treasurer denied the protest and

claimed that FPIC cannot be considered a COMMON CARRIER engaged in the Transportation

business, and thus cannot claim exemption from the payment of tax onits gross receipts. The issue

here is whether or not FPIC is a COMMON CARRIER?

The SC ruled that FPIC is a Common carrier. A Common carrier may be defined broadly as

one who holds himself out to the public as engaged in the business of transporting person or

property from place to place, for compensation, offering his services to the public generally. The

definition of COMMON CARRIER in Article 1732 of the civil code makes no distinction as to the

means of transporting, as long as it is by land, water or air. FPIC is engaged in the business of

transporting or carrying, petroleum product for hire as a public employment.

TRANS ORIENT CONTAINER TERMINAL SERVICES vs. CA

MARCH 19, 2002

Trans Orient is a sole proprietorship customs broker while UCPB is the insurer of SMC

UCPB brought as suit as SMC‘s subrogee against petitioner. Trans Oreint contends that it could not

be held liable as it is not a common carrier rather a private one because a s a customs broker and

warehouseman, she does not discriminately hold her services out to the public but only offers the

same to select parties with whom she may contract in the conduct of her business.

ISSUE: WON petitioner is a common carrier? YES.

HELD: Article 1732 makes no distinctions between those whose principal business activity is the

carriage of persons or goods or both from one who does such carrying only as an ancillary activity.

It also avoids making distinctions between a person or enterprise offering transportation services in

a regular or scheduled basis and one offering such service on an occasional basis.

There is a greater reason for holding petitioner to be a common carrier because the

transportation of goods is an integral part of her business. To uphold Trans Orient contention would

be to deprive those with whom she contracts the protection that the law affords them

notwithstanding the fact that he obligation to carry goods for her customers is part and parcel of

petitioner‘s business.

FIRST MALAYAN LEASING VS CA

209 SCRA 661

Crisostomo Vitug filed a case against the defendant, FMLFC to recover damages for physical

injuries, loss of personal effects, and the wreck of his car as a result of a collision, involving his car,

another car and an Isuzu cargo truck registered in the name of FMLFC and driven by one Crispin

Sicat. FMLFC denied any liability alleging that it was not the owner of the truck because it had sold

the same to Vicente Trinidad.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 11

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

ISSUE: WON FMLFC should be held liable. YES.

HELD: The court has consistently ruled that regardless of ho the actual owner of a motor vehicle

might be, the registered owner is the operator of the same with respect to the public and third

persons, and as such directly and primarily responsible for the consequence of its operation. In

contemplation of law, the owner/operator of record is the employer of the driver, the actual operator

and employer being considered merely as agent.

HOME INSURANCE CO. VS. AMERICAN STEAMSHIP AGENCIES, INC.

23 SCRA 24

Home Insurance a Peruvian firm shipped fishmeal through the SS Crow borough consigned

to San Miguel Brewery, which was insured by the Home Insurance Co. The cargo arrived with

shortages, SMB demanded and Home Insurance Co. paid P14, 000 in settlement for SMB‘s claim.

HIC filed for recovery of P 14, 000 from Luzon Stevedoring and American Steamship agencies.

The court absolved Luzon but ordered American Steamship to reimburse the P14, 000.00 to HIC,

declaring that Art. 587 of the code of commerce makes the ship agent civilly liable for damages in

favor of 3rd persons due to the conduct of carriers captain and that the stipulation in the charter

owner from liability is against public policy under Art 1744 of the New Civil Code. On appeal, the

SC held that the provisions on COMMON CARRIER should not apply where the common carrier

is not acting as such but as a private carrier. The Stipulation in the charter party absolving the

owner from liability for loss due to the negligence of its agent would be void only of strict public

policy governing COMMON CARRIER ids applied. Such policy has no force where the public at

large is not involved, as the case of a ship totally chartered for the use of a single party. (Asked in

the 1980, 1981, 1984, 1985, 1987, 1991 BAR)

LOADSTAR SHIPPING CO. INC, VS, CA

G.R. No. 131621, September 28, 1999

Even without certificate of pubic convenience: Common carrier

A certificate of public convenience is not a requisite for the incurring of liability under the

Civil Code provisions governing common carriers. That liability arises the moment a person or firm

acts as a common carrier, without regard to whether or not such carrier has also complied with the

requirements of the applicable regulatory statute and implementing regulations has been granted a

certificate of public convenience or other franchise.

The concept of COMMON CARRIER coincides well with the notion of ―public service‖

under the Public Service Act (CA 1416, as a amended), which at least partially supplements the law

on COMMON CARRIER as set forth in the Civil Code. Under Section 13, par. (b) of the PSA,

―public service‖ includes every person that nor or hereafter may own, operate, manger, or control in

the Philippines , for hire or compensation, with general or limited clientele, whether permanent,

occasional or accidental, and done for general business purposes, etc.

LASTIMOSO VS. DOLIENTE

1 SCRA 769

In the case of Doliente M/V Doliente was not held liable for the death of Pablo Lastimoso

when a fire occurred because there was no evidence that Doliente was previously engaged in the

business of transporting passengers, as the ill-fated trip was merely a trial run. Hence, it was not

required to exercise Extraordinary Diligence in the vigilance of goods and safety of the passengers

aboard the Doliente, nor was it was bound to carry the passengers safely as far as human foresight

can provide, using the utmost diligence of a very cautious person.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 12

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

CHAPTER II

COMMON CARIER OF GOODS

RESPONSIBILITY/VIGILANCE OVER GOODS

Art. 1734. Common carriers are responsible for the loss, destruction, or deterioration of the goods, unless

the same is due to any of the following causes only:

(1) Flood, storm, earthquake, lightning, or other natural disaster or calamity;

(2) Act of the public enemy in war, whether international or civil;

(3) Act of omission of the shipper or owner of the goods;

(4) The character of the goods or defects in the packing or in the containers;

(5) Order or act of competent public authority.

Art. 1735. In all cases other than those mentioned in Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the preceding article, if the

goods are lost, destroyed or deteriorated, common carriers are presumed to have been at fault or to have

acted negligently, unless they prove that they observed extraordinary diligence as required in Article

1733.

NATURAL DISASTER/FORTUITOUS EVENT

A fortuitous event covers not only acts of God (lightning, earthquake, shipwreck, etc.) but also

act of man (war, Strikes, homicide, recklessness of other drivers, latent mechanical defect etc.) A

common carrier liability does not extend to damages caused by a fortuitous event as expressed in

Article 1174 that ―except in cases expressly specified by law, or otherwise declared by stipulation, or

when the nature of the obligation required the assumption of risk, no person shall be responsible for

events which could not be foreseen, or which, though foreseen, were inevitable‖. After all, the carrier

is not an insurer against all risks of travel. If a common carrier would be an insurer of the passenger‘s

safety, it ought not be liable in case of death of, or injuries to, passengers, although not negligent. But

the common carrier‘s liability rests upon negligence, its failure to exercise the utmost diligence that

the law requires.

Art. 1736. The extraordinary responsibility of the common carrier lasts from the time the goods are

unconditionally placed in the possession of, and received by the carrier for transportation until the same

are delivered, actually or constructively, by the carrier to the consignee, or to the person who has a right

to receive them, without prejudice to the provisions of Article 1738.

Art. 1737. The common carrier's duty to observe extraordinary diligence over the goods remains in full

force and effect even when they are temporarily unloaded or stored in transit, unless the shipper or owner

has made use of the right of stoppage in transitu.

Art. 1738. The extraordinary liability of the common carrier continues to be operative even during the

time the goods are stored in a warehouse of the carrier at the place of destination, until the consignee has

been advised of the arrival of the goods and has had reasonable opportunity thereafter to remove them or

otherwise dispose of them.

2. LIABILITY FOR LOSS; PRESUMPTION OF NEGLIGENCE

PLANTERS PRODUCRS, INC VS CA

226 SCRA 476

The SC held that ―what a carrier in the ordinary course of business transports goods as a

common carrier and thereby bound by law to observe extraordinary diligence, the entering into a

charter party, where the ship captain, its officers and compliments are under the employ of the

shipowner and therefore continue to be under its direct supervision and control, does not transform

the carrier into a private carrier for a such purpose. This is because the charterer, a stranger the crew

and the ship, cannot be charged with the duty to care for his cargo when the charterer does not have

any control of the means of doing so. A common or public carrier shall remain as such,

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 13

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

notwithstanding the charter of the whole or portion of a vessel, provided the charter is limited to

the ship only, as in the case of time charter or voyage charter. It is only when the charter includes

both the vessel and its crew, as in the case of time charter or voyage charter. It is only when the

charter includes both the vessel and its crew, as in a bareboat or demise charter, that a common

carrier becomes private, at least insofar as the particular voyage covering the charter party is

concerned.

COMPARISON AND CONTRASTS: CARRIAGE OF CARGO & CARRIAGE OF PASSENGERS

CARRIAGE OF CARGO CARRIAGE OF PASSENGERS

1. In case of loss, destruction and deterioration 1. The same presumption applies

of the goods, common carriers are presumed to

be at fault or have acted negligently, unless they

prove that they exercise extraordinary diligence.

2. Mere proof of delivery of goods in good 2. As long as it is shown that there exists a relationship

order and the subsequent arrival of the same between the passenger and the common carrier and

good at the place of destination makes for a that injury or death took place during the existence of

prima facie case against the carrier (Coastwise the contract, the courts need not make an express

Lighterage Corp. vs. CA, 245 SVRA 796). finding of fault or negligence of common carriers. The

law imposes upon common carriers strict liability.

Reason for the presumption: As to when and

how the goods wete damaged in transit is a Reason for the presumption: the contract between the

matter peculiarly within the knowledge of the passenger and the carrier imposes on the latter the duty

carrier and its employees (Mirasol vs Dillar, 53 to transport the passenger safely; hence, the burden of

Phil 124). explaining should fall on the carrier. The doctrine of

res ipsa loquitor applies.

3. The cause of action is negligence, particularly 3. Same cause of action.

culpa contractual.

Article 1752 of the New Civil Code applies, wherein the law of the country to which

the goods are to be transported governs the liability in case of their loss, destruction or

deterioration.

BANKERS AND MANUFACTURERS ASSURANCE CORP. V. CA

214 SCRA 433

108 cases of copper tubings were imported by Ali trading Company. The tubings insured by

petitioner and arrived in Manila on board the vessel s/s ―Oriental Ambassador‖ on November 4,

1978, and turned over to private respondent E. Razon, the manila arrastre operator upon discharge

at the waterfront. The carrying vessel is represented in the Philippines by its agent, F. E. Zuelig and

Co. Inc. Upon inspection by the importer, the shipment allegedly, found to have sustained loses by

way of theft and pilferage for which petitioner, as insurer, compensated the importer in the amount

of P31, 014.00.

Petitioner, in subrogation of the importer-consignee and on he basis of what it asserts had

been already established-that a portion of the shipment was lost through theft and pilferage.-

forthwith concludes that the burden of proof of proving a case of non-liability shifted to private

respondents, one of whom, the carrier, being obligated to exercise extraordinary diligence in the

transport and care of the shipment. He implication of petitioner‘s statement is that private

respondents have not shown why they are not liable.

ISSUE: WON the carrier is liable?

HELD: It must be underscored that the shipment involved in the case at the bar was

―containerized‖. The goods under this arrangement are stuffed, packed, and loaded by the shipper at

a place of its choice, usually his own warehouse, in the absence of the carrier. Consequently, the

recital of the bill of lading for goods thus transported ordinary would declare ―Said to Contain‖,

shippers Load and Count‖, full container Load‖, and the amount or quantity of goods in the

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 14

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

container in a particular package is only prima facie evidence of the amount or quantity which may

be overthrown by parol evidence.

It logically follows that the case at bar presents no occasion for the necessity of discussing the

diligence required of a carrier or the theory of prima facie liability of the carrier, for from all

indications, the shipment did not suffer loss or damage while it was under the care, or of the arrastre

operator, it must be added.

BELGIAN OVERSEAS CHARTERING & SHIPPING N.V. vs. PHIL. FIRST

INSURANCE CO. INC.

(383 SCRA 23)

On June 13, 1990 CMC Trading shipped on board the M/V Anangel Sky at Humburg,

Germany, 242 coils of various Prime Cold rolled steel sheets to be transported to Manila consigned

to Philippine Steel Trading Corporation.

On July 28, 1990, M/V Anangel Sky arrived at the port of Manila, and within subsequent

days, discharged the subject cargo. Four (4) coils were found to be in the bad order. Finding the 4

coils in their damage state to be unfit for the intended purpose.

Despite receipt of a formal demand, defendants appellees refused to submit for the

consignee‘s claim. Consequently, plaintiff appellant paid the consignee P506, 086.50 and was

subrogated to the latter‘s rights and causes of action against defendants-appellees.

In impugning the property of the suit against them, defendants appellees imputed that the

damage &/or loss was due to reshipment damage, to the inherent nature, vice or defect of the goods

or to perils, danger & accidents of the sea, or to insufficiency of packing thereof, or to the act of

omission of the shipper of the goods or their representatives.

In addition thereto, defendants also argued that their liability, if there be any, should not

exceed the limitations of liability provided for in the bill of lading and other pertinent laws. They

likewise averred that, in any event, they exercised due diligence and foresight require by the law to

prevent any damage/loss to the said shipment.

RTC dismissed the complaint because they had failed to overcome the presumption of

negligence imposed on carriers.

ISSUE: WON petitioners have overcome the presumption of negligence of common carrier? NO.

HELD: Petitioners contend the common carriers should not be applied on the basis of the loan

testimony offered by private respondents. This is UNTENABLE. Well settled is the rule that

common carriers, from the nature of their business and for reasons of public policy, bounded to

observe extraordinary diligence and vigilance with respect to the safety of the goods and the

passengers they transport.

Thus, common carriers are required to render service with greatest skill and foresight and to

use al reasonable means to ascertain the nature and characteristics of the goods tendered for

shipment, and to exercise due care in the handling and stowage, including such methods as their

nature requires.

The extraordinary responsibility lasts from the time the goods are unconditionally placed in

the possession of and received for transportation by the carrier until they are delivered, actually and

constructively, to the consignee or to the person who has right to receive them. This strict

requirement is justified by the fact that, the riding public enters into a contract of transportation

with common carriers without a hand or a voice in the preparation such contract.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 15

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Owing to his high degree of diligence required of them, common carriers, as a general rule,

are presume to have been at fault or negligent if the goods they transported deteriorated or got lost

or destroyed. That is, unless they prove that the exercised extraordinary diligence in transporting

the goods. In order to avoid responsibility for any loss or damage therefore, they have the burden of

proving that they observe such diligence.

Mere proof of delivery of the goods in good order to a common carrier and of their arrival in

bad order at their destination constitutes a prima facie case of fault or negligence against the carrier.

If no adequate explanation is given as to how the deterioration, loss or destruction of the goods

happened, the transported shall be held responsible.

In the case, the petitioner failed to rebut the prima facie presumption of negligence. Although

the words ―metal envelopes rust stained and slightly dented‖ were noted on the bill of lading, there

is no showing that petitioners exercised due diligence to forestall or lessen the loss.

Having been in the service for several years, the master of the vessel should have known at

the outset that metal envelopes in said state would eventually deteriorate when not properly stored

while in transit. Equipped with the proper knowledge of the nature steel sheets in coils and of the

proper way of transporting them, the master of the vessel and his crew should have undertaken

precautionary measures to avoid possible deterioration of the cargo. But NONE of these measures

were taken.

Petitioners contend that they are exempted from the liability under Art. 1734 (4) of the Civil

Code in that character of the goods or defect in the packing or the containers was the proximate

cause of the damage. The aforesaid exception only refers to cases when goods are lost or damaged

while in transit as a result of natural decay of perishable goods or the fermentation or evaporation of

substances liable therefore. None of these is presented in this case.

Further even if the fact of improper packing was known to the carrier or its crew or was

apparent upon ordinary observation, it is NOT relieved of liability for loses or injury resulting there

from, one it accepts the goods notwithstanding such condition.

Thus, petitioners have NOT successfully proven the application of any of the mentioned

exemption in this case.

3. EXEMPTION FROM LIABILITY/DEFENSE OF COMMON CARRIER

Art. 1739. In order that the common carrier may be exempted from responsibility, the natural disaster

must have been the proximate and only cause of the loss. However, the common carrier must exercise due

diligence to prevent or minimize loss before, during and after the occurrence of flood, storm or other

natural disaster in order that the common carrier may be exempted from liability for the loss, destruction,

or deterioration of the goods. The same duty is incumbent upon the common carrier in case of an act of

the public enemy referred to in Article 1734, No. 2.

CHARACTERISTICS OF A FORTUITOUS EVENT

If a fortuitous event is proved, the carrier is absolved from liability. But the fortuitous event

must not concur with negligence; otherwise, it is no longer a defense. In other words, the fortuitous

even must be the sole element relied upon as held in Batangas Co. v. Caguimbal). In the case of

Yobido v. CA, the SC described the characteristics of a fortuitous event as:

1. The cause of the unforeseen and unexpected occurrence, or failure of the debtor of comply

with his obligations, must be in dependent of human will;

2. It must be impossible to foresee the event, which constitutes the caso fortuito;

3. The occurrence must be such as to render it impossible for the debtor to fulfill his

obligation in a normal manner; and

4. The obligor must be free from any participation in the aggravation of the injury

resulting to the creditor.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 16

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Based on these pronouncements, a bus company cannot be exempted from liability from a tire

blow-out (as discussed earlier) which cannot be classified simply as a fortuitous event, in the absence

of showing that it has exercise the EOD required of common carrier under the law.

Article 1739 provides that while the defenses under Article 1734 are available to common

carrier in order that the common carrier may be exempted from responsibility, the natural disaster

must have been the proximate and only cause of the loss. However, the common carrier must exercise

due diligence to prevent or minimize loss before, during and after the occurrence of the flood, storm,

or other natural disaster in order that the common carrier may be exempted from liability for the Loss

or deterioration of the goods. It need not, however, be the immediate cause, it is sufficient if the

immediate cause or the final act was set in motion by the natural calamity or disaster & followed it in

natural continuous sequence, unbroken by any efficient intervening cause.

COMMON CARRIER IS STILL LIABLE FOR A LOSS CAUSE BY A NATURAL DISASTER IN THE

FOLLOWING INSTANCES (1957, 1987, & 1998 BAR):

1) When the natural disaster is not the proximate and only cause of the loss;

2) When the common carrier failed to exercise due diligence to prevent or minimize the loss

before, during and after the occurrence of the natural disaster; and

3) When the common carrier negligently incurs in delay in transporting the goods.

Art. 1740. If the common carrier negligently incurs in delay in transporting the goods, a natural disaster

shall not free such carrier from responsibility.

Art. 1741. If the shipper or owner merely contributed to the loss, destruction or deterioration of the goods,

the proximate cause thereof being the negligence of the common carrier, the latter shall be liable in

damages, which however, shall be equitably reduced.

Art. 1742. Even if the loss, destruction, or deterioration of the goods should be caused by the character of

the goods, or the faulty nature of the packing or of the containers, the common carrier must exercise due

diligence to forestall or lessen the loss.

Art. 1743. If through the order of public authority the goods are seized or destroyed, the common carrier

is not responsible, provided said public authority had power to issue the order.

Art. 1744. A stipulation between the common carrier and the shipper or owner limiting the liability of the

former for the loss, destruction, or deterioration of the goods to a degree less than extraordinary diligence

shall be valid, provided it be:

(1) In writing, signed by the shipper or owner;

(2) Supported by a valuable consideration other than the service rendered by the common carrier; and

(3) Reasonable, just and not contrary to public policy.

Art. 1745. Any of the following or similar stipulations shall be considered unreasonable, unjust and

contrary to public policy:

(1) That the goods are transported at the risk of the owner or shipper;

(2) That the common carrier will not be liable for any loss, destruction, or deterioration of the goods;

(3) That the common carrier need not observe any diligence in the custody of the goods;

(4) That the common carrier shall exercise a degree of diligence less than that of a good father of a

family, or of a man of ordinary prudence in the vigilance over the movables transported;

(5) That the common carrier shall not be responsible for the acts or omission of his or its employees;

(6) That the common carrier's liability for acts committed by thieves, or of robbers who do not act with

grave or irresistible threat, violence or force, is dispensed with or diminished;

(7) That the common carrier is not responsible for the loss, destruction, or deterioration of goods on

account of the defective condition of the car, vehicle, ship, airplane or other equipment used in the

contract of carriage.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 17

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

THE PHILIPPINE AMERICAN GENERAL INSURANCE CO., INC. VS MGG

MARINE SERVICES, INC.

G.R. NO. 135645, March 8, 2002

San Miguel Corporation insured several bottle cases with an aggregate value of

P5,836,222.80 with Philippine American General Insurance Company (PHILAMGEN). The cargo

was loaded aboard the M/V Peatheray Patrick G to be transported from Mandaue City to Bislig,

Surigao del Sur. The weather was said to be clam by the start of the voyage. The following day,

the said vessel subsequently sunk off Cawit point, Cortes, Surigao del Sur. As a consequence, the

cargo belonging to San Miguel was lost.

San Miguel claimed the amount of lost from PHILAMGEN. Upon request by

aforementioned company, Mr. Sayo, a surveyor from Manila went to pace of sinking to investigate

circumstances of loss of cargo. He stated that the vessel was structurally sound and concluded that

the proximate cause of the listing and subsequent sinking of the vessel was the shifting of ballast

water from starboard to portside. This affected the stability of the vessel.

Petitioner paid San Miguel the full amount stated in the insurance contract. As subrogee of

San Miguel, it filed a collection case against MCG Marine Service s to recover amount it paid to

San Miguel.

Meanwhile, The Board of Marine Inquiry conducted its own investigation of the sinking of

the M/V Peartheray Patrick G. the Board rendered a decision exonerating the captain and its crew

from any administrative liability. It found that the cause of sinking was the existence of strong

winds and enormous waves a fortuitous event that could not have been foreseen. It was further held

that it is this fortuitous event that was the proximate cause of sinking.

The RTC of Makati promulgated a decision finding respondent solidary liable for the loss of

San Miguel Corporation‘s cargo and ordering them to pay petitioner the full amount for the lost

cargo plus legal interest, attorney‘s fees and cost of suit. MCG Marine appealed to CA, it reversed

ruling of RTC.

ISSUE: WON MCG Marine services should be liable for the loss of San Miguel‘s cargo?

HELD: NO, MCG Marine Services could not be held liable for the loss of the cargo occurred, as a

consequence of a fortuitous event and such event was the proximate and only cause of the loss.

Common carriers, from the nature of their business and for reasons of public policy are

mandated to observe extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods and for the safety of

the passengers transported by them. Due to this, common carriers as a general rule are presumed to

have been at fault or negligent if the goods transported by them are lost, destroyed or if the same

deteriorated.

The presumption of fault or negligence does not arise in the cases enumerated under Art.

1734 of the Civil Code. Common carriers are responsible for the loss, destruction or deterioration

of goods unless the same is due to any of the following causes only:

a. Flood, storm, earthquake, lightning or other natural disaster or calamity

b. On of the public enemy whether international or civil.

c. Act or omission of the shipper or owner of the goods

d. Character of the goods or defects in the packing or in the containers.

e. Order or act of competent authority.

In order that a common carrier is absolved from liability due to natural disaster, it must be

further shown that such natural disaster or calamity was the proximate and only cause of loss, there

must be an entire exclusion of human agency from the cause of injury or less.

The Board or Marine Inquiry found out that the loss of cargo was due solely to the

existence of a fortuitous event, particularly the strong winds and huge waves.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 18

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

An event is said to be fortuitous if the following elements concur:

a. Cause of the unforeseen and unexpected occurrence, or the failure of the debtor to comply

with his obligations, must be independent of human will.

b. Must be impossible to foresee the event, or it can be foreseen but impossible to avoid.

c. Occurrence must be such as to render it impossible for the debtor to fulfill his obligation

in a normal manner.

d. The obligor must be free from any participation in the aggravation of the injury resulting

to the creditor.

YOBIDO vs. COURT OF APPEALS

October 17, 1997

Tito and Leny Tumboy, together with their minor children boarded a Yobido bus operated by

herein petitioner in Mangagoy, Surigao del Sur. Leny Tumboy alleged that the bus was overloaded,

and the driver was driving at a very high speed, so she cautioned him to slow down. However, he

paid attention until the front left tire of the bus blew out, causing the bus to fall into a ravine where

it stuck into a tree. The incident caused the death of Tito Tumboy. Other passengers of the bus

were injured.

Leny Tumboy filed a complaint for breach of contract of carriage against Yobido. Yobido

contends that she is not liable because the tire blow-out was a fortuitous event which exempts the

carrier from liability. Her witnesses testified that the tire was installed five days before the

incident, and that it was of good quality.

ISSUE: WON the tire blow-out is a fortuitous event as would exempt Yobido from liability

arising form the contract of carriage? NO.

HELD: The tire blow-put may not be a fortuitous event. Human factors are involved. The fact

that the tire was new did not imply that it is entirely free from manufacturing defects or that it

was properly mounted on the vehicle. Accidents caused either by defects of the automobile or

through the negligence of the driver is not a fortuitous event.

A common carrier may not be absolved from liability in case of force majeure alone.

The common carrier must still prove that it was not negligent in causing the death or injury

resulting from an accident. In the case at bar, while it may be true that the tire that blew-up was

still good because the grooves of the tire were still visible, this fact alone does not make the

explosion of the tire a fortuitous event. No evidence was presented to show that the accident

was due to adverse road conditions or that precautions were taken by the jeepney driver to

compensate for any conditions liable to cause accidents. The sudden blowing-up, therefore,

could have been caused by too much air pressure injected into the fire coupled by the fact that

the jeepney was overloaded and speeding at the time of the accident.

TAN CHIONG SIAN v. INCHAUSTI & CO.

22 Phil 152

The defendant received in Manila from Ong Bieng Siap, bundles and cases of goods to be

conveyed by the steamer Sorsogon to Gubat, Sorsogon where they were to be transshipped to

another vessel of the defendant for transportation to Catarman, Samar, then to be delivered to a

Chinese shipper, Tan Chiong Sian, with whom the defendant made a shipping contract. The

steamer Sorsogon arrived at Gubat with goods, and as the lorcha Pilar was not yet there, the goods

were unloaded and stored in the defendant‘s warehouse.

Several days later, the lorcha Pilar arrived and the goods were taken aboard. Before Pilar

could leave for its destination, a storm arose from the Pacific passing Gubar and driving Pilar and

its cargo upon the shore and wrecked it. The laborers of the defendant proceeded to gather up the

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 19

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

merchandise of the plaintiff, and as it was impossible to preserve it, it was sold at public aution for

P1,693.37. Plaintiff filed an action for damages in the amount of P20,000.00. Lower decided that

the plaintiff was entitled only to P14,642.63. Defendant appealed.

ISSUE: WON defendant Inchausti is held liable for damages? NO.

HELD: It is a fact not disputed, and admitted by the plaintiff that Pilar was stranded and wrecked

on the coast of Gubat as a result of a violent storm from the Pacific, and it is a proven fact that the

loss or damage of the goods was due to force majeure which caused the wreckage of said craft.

According to Art. 361 of the Code of Commerce ―merchandise shall be transported at the risk and

venture of the shipper, unless the contrary be expressly stipulated.‖ No such stipulation appears on

record, therefore, all damages and impairment suffered by the goods by reason of accident, force

majeure or by virtue of the nature or defect of articles are for the account and risk of the shipper.

Defendant, therefore, is not liable for the damage occasioned as a result of the stranding of Pilar

because of the hurricane that overtook it.

The record bears no proof that said loss caused by the destruction of Pilar occurred through

the carelessness or negligence of the defendant, its agents or patron of the lorcha. The defendant as

well as its agents and patron had a natural interest in preserving the craft – an interest equal to that

of the plaintiff. The record disclose that Pilar was manned by an experienced patron and a

sufficient n umber of crewmen plus the fact that it was fully equipped. The crewmen took all the

precautions that any diligent man should have taken whose duty it was to save the boat and its

cargo, and by the instinct of self-preservation, of their lives. Considering, therefore, the conduct of

the men of the defendant in Pilar and of its agents during the disaster, the defendant has not

incurred any liability whatsoever for the loss of the goods, inasmuch as such loss was the result of a

fortuitous event or force majeure, and there was no negligence or lack of care or diligence on the

part of the defendant or its agent.

EASTERN SHIPPING LINES, INC. v. IAC

150 SCRA 463

These two cases, both for the recovery of the value of the cargo insurance, arose from the

same incident, the sinking of the M/S ASIATIC when it caught fire, resulting in the total loss of

ship and cargo.

In G.R. No. 69044, the M/s ASISTIC, a vessel operated by petitioner, loaded at Kobe, Japan

for transportation to Manila, 5,000 pieces of colorized lance pipes in 28 packages valued at

P256.039 consigned to Phil. Blooming Mills Co., Inc. and 7 cases of spare parts valued at

P92,361.75 consigned to Central Textiles Mills, Inc. Both set of goods were insured against

marine risk for their stated value with respondent Development Insurance and Surety Corporation.

In G.R. No. 71478, the same vessel took on board 128 cartons of garment fabrics and

accessories, in 2 containers, consigned to Mariveles Apparel Corporation, and two cases of

surveying instruments consigned to Aman Enterprises and General Merchandise. The 128 cartons

were insured by respondent Nisshin Fire & Marine Insurance Co., and Dowa Fire & Marine

Insurance Co., Ltd.

Enroute for Kobe, Japan, to Manila, the vessel caught fire and sank, resulting in the total loss

of ship and cargo. The respective respondent Insurers paid the corresponding marine insurance

values to the consignees concerned and were thus subrogated unto the rights of the latter as the

insured.

ISSUES: 1. Which law should govern – the Civil provisions on Common carriers or the Carriage of

Goods Sea Act (COGSA)?

2. Who has the burden of proof to show negligence on the carrier?

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2005 Edition: Jeneath Kingco

2007 Edition: Sol Marie Andoy

The Fraternal Order of St. Thomas More 20

Transportation Law – Atty. Josephine Valencia

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

HELD: The law of the country to which the goods are to be transported governs the liability of the

common carrier in case of their loss, destruction or deterioration. As the cargoes in question were

transported from Japan to the PhiL, the liability of the petitioner is governed primarily by the Civil

Code. However, in all matters not regulated by said Code, the rights and obligations of common

carrier shall be governed by the Code of Commerce and by special laws. Thus, the COGSA, a

special law is suppletory to the provisions of the Civil Code.

Under the Civil Code, common carriers, from the nature of their business and for reasons of

public policy, are bound to observe extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over goods, according

to all the circumstances of each case. Common carriers are responsible for the less, destruction, or

deterioration of the goods unless the same is due to any of the following causes only (Art. 1734,

NCC):

―(1) Flood, storm, earthquake, lightning or other natural disaster or calamity; xxx‖

The carrier claims that the loss of the vessel by fire exempts it from liability under the

phrase ―natural disaster or calamity.‖ However, fire many not be considered a natural disaster or

calamity. It does not fall within the category of an act of God unless caused by lightning or by

natural; disaster or calamity. Thus, under Art. 1735, the carrier shall be presumed to have been at

fault or have acted negligently, unless it proves that it has observed the extraordinary diligence

required by law.

In this case, the respective Insurers, as subrogees of the cargo shippers, have proven that

the transported goods have been lost. Petitioner Carrier has also proven that the loss was caused by

fire. The burden then is upon Petitioner Carrier to prove that it has exercised the extraordinary

diligence required by law. Having failed to discharge the burden of proving that it had exercised the

extraordinary diligence required by law, petitioner cannot escape liability for the loss of the cargo.

MAURO GANZON vs. COURT OF APPEALS

May 30, 1988

The private respondent instituted in the Court of First Instance an action against the petitioner

for damages based on culpa contractual.

Gelacio Tumambin contracted the services of Maruo B. Ganzon to haul 305 tons of scrap

iron from Mariveles, Bataa, to the port of Manila on board the lighter LCT ―Batman.‖ Gelacio

Tumambing delivered the scrap iron to defendant Filomeno Niza, captain of the lighter. When

about half of the scrap iron was already loaded, Mayor Jose Advincula of Mariveles, Bataan,

arrived and demanded P5,000.00 from Gelacio Tumambing. The latter however refused which

resulted to a heated argument between them.

On a subsequent date, Acting Mayor Basilio Rub, accompanied by three policemen,

ordered captain Filomeno Niza and his crew to dump the scrap iron where the lighter was docked.

Later on Acting Mayor Rub issued a receipt stating that the Municipality of Mariveles had taken

custody of the scrap iron.