Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Olatomide Familusi

Uploaded by

Raghad AdelCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Olatomide Familusi

Uploaded by

Raghad AdelCopyright:

Available Formats

Creative Education, 2019, 10, 637-649

http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce

ISSN Online: 2151-4771

ISSN Print: 2151-4755

Breast Reconstruction Awareness: Targeting

Health Literacy through Community

Engagement

Olatomide Familusi1, Fabiola Enriquez1, Justin Fox1, Irfan Rhemtulla1, Ari Brooks2,

Carmen Guerra3, Paris Butler1*

1

Division of Plastic Surgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

2

Department of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

3

Department of Internal Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

How to cite this paper: Familusi, O., Enri- Abstract

quez, F., Fox, J., Rhemtulla, I., Brooks, A.,

Guerra, C., & Butler, P. (2019). Breast Re-

Background: After mastectomy, women of color undergo breast reconstruc-

construction Awareness: Targeting Health tion at disproportionately lower rates than their Caucasian counterparts. In

Literacy through Community Engagement. this study we address health literacy, a modifiable contributor to this dispari-

Creative Education, 10, 637-649. ty, through community engagement. Methods: In collaboration with a large

https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.104046

church in West Philadelphia PA, the Abramson Cancer Center, the division

Received: December 29, 2018 of plastic surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, and with funding from

Accepted: April 1, 2019 the Plastic Surgery Foundation, the authors developed a health awareness

Published: April 4, 2019 symposium centered on breast reconstruction. This program, targeting

Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and

women of color, included lectures, patient testimonials and a Q&A session.

Scientific Research Publishing Inc. Participants completed pre and post-symposium surveys focusing on the

This work is licensed under the Creative availability, timing and options for breast reconstruction. Results: A total of

Commons Attribution International 63 community members attended the symposium. Participants were mostly

License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

female (88.9%) and of African American descent (87.3%). Half were current

Open Access breast cancer patients while 24% identified as family members/friends of a

breast cancer patient. Prior to the session, 12.7% of participants were unaware

of breast reconstruction as a treatment option after mastectomy, while 42.8%

were unaware of insurance coverage for breast reconstruction and contrala-

teral balancing procedures. There were statistically significant increases in the

number of participants responding correctly to questions regarding insurance

coverage, timing of reconstruction, and reconstruction options after the pro-

gram as compared to before. Conclusions: The etiology of the existing dis-

parity in breast reconstruction is complex and multifactorial. Partnerships

between community groups and healthcare professionals from plastic surgery

and breast surgery to create targeted interventions can improve community

awareness in an effort to alleviate the current disparity.

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 Apr. 4, 2019 637 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

Keywords

Breast Reconstruction, Disparity, Health Literacy, Community Engagement,

Patient Education

1. Introduction

With the introduction of The Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act (Depart-

ment of Health and Human Services, 2018), mandating complete insurance cov-

erage of reconstructive procedures related to breast cancer surgery, post mas-

tectomy breast reconstruction has become well regarded as a standard of care.

Unfortunately, despite well-documented psychosocial benefits (Fanakidou et al.,

2018; Eltahir et al., 2013), women of color continue to undergo breast recon-

struction at disproportionately lower rates than their Caucasian counterparts

(Butler et al., 2016; Nelson et al., 2012). This disparity persists even when both

insurance status and geographical access to a plastic surgeon are taken into ac-

count (Butler et al., 2017). The underlying etiology of the observed trend

represents a complex interplay between patient preference/choice, cultural im-

age of self, beliefs about medicine, health literacy and awareness, and physician

implicit/explicit bias. In this study, we address community health literacy, one of

the modifiable contributors to this disparity.

Identifying and implementing strategies to mitigate the various disparities

observed in surgery have rightfully become a major research focus within the

field; to the extent that in 2015 the American College of Surgeons and the Na-

tional Institutes of Health-National Institute of Minority Health and Disparities

convened a research summit to develop a national surgical disparities research

agenda. Fostering engagement and community outreach in order to optimize

patient education and health literacy was identified as one of the five priorities

for surgical disparities research (Haider et al., 2016). Interventions concentrating

on community engagement have been successfully implemented across multiple

surgical disciplines (Hoffman et al., 2016; Santos et al., 2017; Hempstead et al.,

2018; Hurd et al., 2003). Through a community-based symposium directed at

women of color in Philadelphia, we sought to improve knowledge of breast re-

construction options after oncologic breast surgery.

2. Methods

In collaboration with a large well-known church in West Philadelphia, PA, the

Abramson Cancer Center, and the division of Plastic Surgery at the University of

Pennsylvania, we developed a health awareness symposium about breast recon-

struction after mastectomy. The 4-hour program, held in April of 2017, con-

sisted of short lectures on breast health, breast cancer screening, treatment mod-

alities, breast reconstruction options, patient testimonials, and concluded with a

panel-based Q & A session. The lecture sessions were followed by an exhibitor

fair, during which samples of implants, wigs, bras, and prosthesis were available

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 638 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

for patients to experience. Participants were also introduced to the survivorship

resources provided by the Abramson Cancer Center. These include an annual

survivorship event hosted by the cancer center and long-term clinic and tele-

phone follow up carried out by a breast nurse navigator, several breast health

nurse practitioners, and survivorship/high-risk clinic providers. The number of

participants who presented to the educational session determined the sample size

of the study. All participants were invited to complete pre and post surveys with-

out exclusion criteria. The surveys, designed by the senior author, consisted of

questions about the availability, insurance coverage, timing and options for breast

reconstruction to assess knowledge attainment designed. Survey questions were

formatted as general statements with three response options: true, false and I

don’t know. One question regarding the impact of breast reconstruction on body

image was presented as statement with response options on a 5-point Likert scale

(strongly agree, somewhat agree, neutral, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree).

The pre-symposium survey included an additional seven questions specifically for

symposium participants who were breast cancer patients/survivors.

The Hospital of the University of Philadelphia serves an ethnically diverse re-

gion. Women of color in the local area made up the target demographic for this

intervention. The event was advertised via distribution of over one thousand

physical flyers, advertisements placed in two local West Philadelphia newspapers

for a month prior to the date of the symposium, and email notifications sent

within the University of Pennsylvania Health System. Flyers were distributed by

the Abramson Cancer Center outreach services and the Traci’s BIO-breast can-

cer support group, a local non-profit organization founded by a breast cancer

survivor, that works to support, educate and pamper African American women

diagnosed with cancer. A Plastic Surgery Foundation grant awarded to the se-

nior author funded the program in its entirety.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics on program participant demographics are presented as

means and standard deviations for continuous variables and as numbers and

percentages for categorical variables. Percentage of correct responses for each

individual survey question on the pre and post symposium surveys were com-

pared using Mcnemar’s test for paired data after responses were dichotomized as

correct or incorrect. For ease of analysis, missing and “I don’t know” responses

were categorized as incorrect. All tests were two-tailed and statistical significance

was defined as p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata/IC 13.0

software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

3. Results

A total of 63 community members attended the 4-hour health awareness sympo-

sium. The majority of the attendees were female (n = 56, 88.9%) and of African

American descent (n = 55, 87.3%). Participants were on average 58 years old (SD

12.8). Approximately half (n = 31, 49.2%) of the attendees were current breast

cancer patients or survivors while 23.8% (n = 15) identified as a family member

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 639 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

or friend of a breast cancer patient. 19.1% of participants reported having a high

school diploma or equivalent while 23.8% and 22.2% had college or graduate

degrees respectively. The majority of the symposium attendees were from the

local Philadelphia area, with 33.3% from West Philadelphia, 15.9% from North

Philadelphia and 11.1% from Northwest Philadelphia. Table 1 presents demo-

graphic information of symposium participants. Of the 31 breast cancer pa-

tients/survivors, 35.4% (n = 11) reported undergoing breast reconstruction. All

of these women received their oncologic treatment at hospitals that also pro-

vided breast reconstruction. 81.8% (n = 9) had discussions about reconstruction

with their doctors prior to initiating oncologic treatment. Almost half of those

patients (n = 5) discussed breast reconstruction with friends and family mem-

bers prior to making a decision. Of the 20 women who did not undergo recon-

struction, 45% (n = 9) were offered breast reconstruction by their physician and

declined. A quarter of these women reported being afraid of reconstruction

while 15% (n = 3) were unaware that breast reconstruction was available to

them. 10% of the women in this group reported regretting their decision to forgo

reconstruction. Table 2 presents responses to the breast cancer patient portion

of the pre-symposium survey.

Prior to the educational session, 73% of participants were aware of breast re-

construction as a treatment option after mastectomy surgery. In response to

survey questions about general breast reconstruction, 7.9% of respondents be-

lieved that breast reconstruction could not be performed safely in women over

the age of 60, while 31.8% were unsure. When asked if breast reconstruction

must be done immediately after mastectomy, 12.7% of participants responded

incorrectly while 27% were uncertain of the correct response. 20.6% of partici-

pants were unsure if the need for chemotherapy or radiation therapy precluded a

patient from undergoing breast reconstruction. Less than half (49%) of partici-

pants responded accurately when asked if breast reconstruction was covered by

insurance, while 52.9% of participants were not aware of insurance coverage of

balancing contralateral procedures. 31.8% were unsure of the impact of breast

reconstruction on cancer recurrence and detection.

In response to survey questions about implant reconstruction, 5% of partici-

pants incorrectly believed that implants were the only reconstructive option after

mastectomy while 31.8% were uncertain. Only 14.3% of respondents acknowl-

edged that silicone implants were as safe as saline implants, while 50.8% were

unsure. Only 36.5% of participants appropriately identified a statement indicat-

ing ruptured implants could cause cancer as false while 42.9% of respondents

were unsure of the implication of implant rupture in the development of cancer.

Table 3 presents pre-symposium survey responses. When comparing pre and

post symposium surveys, the percentage of correct responses for all survey ques-

tions increased. Table 4 presents the comparison of pre and post symposium

surveys responses. The percentage of correct responses about insurance coverage

of breast reconstruction increased significantly from 46% to 73% (p = 0.001)

while the percentage of correct responses about insurance coverage of balancing

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 640 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

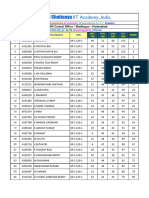

Table 1. Demographics of survey respondents.

N %

Respondents, N (%) 63 100.0

Age in years, mean (STD) 58.1 (12.8)

Female, N (%) 56 88.9

Race, N (%)

African-American/Black 55 87.3

Caucasian/White 3 4.8

Asian 1 1.6

Missing 4 6.4

Ethnicity

Hispanic or Latino 1 1.6

Not Hispanic or Latino 31 49.2

Missing 31 49.2

Education

Some high school 3 4.8

High school or GED 12 19.1

Some College 12 19.1

College degree 15 23.8

Graduate degree 14 22.2

Vocational or trade school 3 4.8

Missing 4 6.4

Patient location

West Philadelphia 21 33.3

South Philadelphia 2 3.2

Southwest Philadelphia 5 7.9

North Philadelphia 10 15.9

Northwest Philadelphia 7 11.1

Northeast Philadelphia 1 1.6

Center City 0 0.0

Other 12 19.1

Missing 5 7.9

Breast reconstruction awareness

I am aware that breast reconstruction is an option

46 73.0

after breast cancer surgery

I am NOT aware that breast reconstruction is

8 12.7

an option after breast cancer surgery

Missing 9 14.3

Interest/Relationship

I am a breast cancer Patient/Survivor 31 49.2

I am the Spouse/Partner of a breast cancer Patient/Survivor 0 0.0

I am a Caregiver for someone with breast cancer 1 1.6

I am a Family Member/Friend of someone with breast cancer 15 23.8

I am a Health Professional 2 3.2

I am a Community Resident/Stakeholder 4 6.4

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 641 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

Table 2. Breast cancer patient survey responses.

Yes No

My doctor talked to me about breast reconstruction

81.8 18.2

before I started treatment.

Reconstruction

I talk to friends or family about breast reconstruction

n = 11 45.5 54.5

before deciding if it was right for me.

Breast reconstruction was offered at my hospital. 100.0 0.0

I was offered breast reconstruction

45.0 55.0

by my doctor but declined it.

No

I was afraid of breast reconstruction. 25.0 75.0

Reconstruction

n = 20 I was not aware breast reconstruction was available. 15.0 85.0

I regret not having breast reconstruction. 10.0 90.0

N = 31. All values represented as percentages.

Table 3. Pre-symposium responses (%).

True False I Don’t Know

1) I can only get breast implants as a form of breast

4.8 46.0 49.2

reconstruction. No other options exist.

2) If I have or need chemotherapy or radiation therapy,

1.6 60.3 38.1

I can’t have breast reconstruction.

3) Breast reconstruction can’t be performed safely in

7.9 46.0 46.1

women over the age of 60.

4) Breast reconstruction is not covered by insurance. 9.5 46.0 44.5

5) My insurance company will pay for me to have a

breast reduction, breast lift, or breast augmentation on 28.6 9.5 61.9

the unaffected breast to match the reconstructed breast.

6) Having breast reconstruction makes my cancer

4.8 49.2 46.0

more likely to return and harder to detect if it does return.

7) Breast reconstruction must be done immediately

12.7 44.4 42.9

after my mastectomy (a surgery to remove the breast).

8) If my breast implant ruptures, I will get cancer 3.2

36.5 60.3

from the ruptured implant.

9) Silicone breast implants are just as safe as saline breast

14.3 17.5 31.8

implants.

10) If your mother or other women in your family don’t

1.6 69.8 28.6

have breast cancer, you are not going to get breast cancer.

11) Mammograms cause cancer. 1.6 73.0 25.4

12) Cancer only spreads when the air hits it. 6.4 71.4 22.2

13) A majority of women who get breast cancer

4.8 71.4 23.8

will die of breast cancer.

14) The only treatment for breast cancer is mastectomy

4.8 73.0 22.2

(a surgery to remove the breast).

Values represented as percentages.

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 642 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

Table 4. Comparison of percentage correct responses for pre and post symposium survey

questions.

Pre Post p-value

I can only get breast implants as a form of breast reconstruction.

46.0 69.8 0.002

No other options exist.

If I have or need chemotherapy or radiation therapy,

60.3 73.0 0.077

I can’t have breast reconstruction.

Breast reconstruction can’t be performed safely in women

46.0 57.1 0.230

over the age of 60.

Breast reconstruction is not covered by insurance. 46.0 73.0 0.001

My insurance company will pay for me to have a breast reduction,

breast lift, or breast augmentation on the unaffected 28.6 65.1 <0.001

breast to match the reconstructed breast.

Having breast reconstruction makes my cancer more

49.2 69.8 0.007

likely to return and harder to detect if it does return.

Breast reconstruction must be done immediately after

44.4 69.8 0.002

my mastectomy (a surgery to remove the breast).

If my breast implant ruptures, I will get cancer from

36.5 71.4 <0.001

the ruptured implant.

Silicone breast implants are just as safe as saline breast implants. 14.3 66.7 <0.001

If your mother or other women in your family don’t have

69.9 76.2 0.455

breast cancer, you are not going to get breast cancer.

Mammograms cause cancer. 73.0 79.4 0.481

Cancer only spreads when the air hits it. 71.4 79.4 0.302

A majority of women who get breast cancer

71.4 82.5 0.144

will die of breast cancer.

The only treatment for breast cancer is mastectomy (a surgery to

73.0 76.2 0.754

remove the breast).

Breast reconstruction can improve a woman’s body image. 55.6 76.2 0.004

Values represented as percentages. Responses to questions 1 - 14 were true, false, or I don’t know. Res-

ponses to question 15 were strongly agree, somewhat agree, neutral, somewhat disagree or strongly disag-

ree. Missing responses were categorized as incorrect.

contralateral procedures, increased from 28.6% to 65.1% (p < 0.001). Pre-symposium,

only 14.3% of participants believed that silicone implants were just as safe as sa-

line implants. This number increased to 66.7% after the educational sessions (p

< 0.001). Compared to 36.5% of respondents in the pre-symposium survey,

57.1% of respondents in the post-symposium survey strongly agreed that breast

reconstruction could improve a woman’s body image (p = 0.0004) (see Figure 1

and Figure 2).

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 643 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

Figure 1. Pre vs. post symposium responses to “breast reconstruction could improve

women’s body image”.

Figure 2. Correct responses on pre vs. post symposium survey (%).

4. Discussion

With increased media attention driven by celebrities like Angelina Jolie (Lebo et

al., 2015), and the advent of breast reconstruction awareness campaigns such as

BRA Day, launched by Dr. Mitchell Brown of Toronto, Canada in 2011 and

adopted in the US the following year, (Breast Reconstruction Awareness, 2018;

Breast Reconstruction Awareness Campaign, 2018) public knowledge of breast

reconstruction has become more common. Despite this, disparities exist in the

rates of breast reconstruction among women of color and their Caucasian coun-

terparts. In 2004, Tseng et al. noted significantly lower rates of breast recon-

struction in African American women (Tseng et al., 2004). Furthermore, their

study revealed that African American women were less likely to be offered re-

ferrals for reconstruction, less likely to accept referrals if offered, less likely to be

offered reconstruction, and less likely to chose reconstruction if offered. Simi-

larly, in an analysis of 48,000 patients from 2005 to 2011, Butler et al. reported

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 644 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

significantly lower rates of immediate breast reconstruction in women of color

despite no association of added surgical morbidity (Butler et al., 2016). Only a

third of the 31 breast cancer patients participating in our symposium underwent

reconstruction. Of the 74.6% who did not, less than half were offered breast re-

construction. Of that same group, 15% were not aware of reconstruction as an

available option and 10% regretted not pursuing reconstructive surgery. Al-

though complex and multifactorial, we believe that poor health literacy in the

context of breast reconstruction is one of the major contributors to the existing

disparity. In a population based study of disparities in post mastectomy recon-

struction, Alderman et al. notes that between a third and a half of minority

women in their study (n = 805) desired more information about breast recon-

struction, as compared to 17.0% of Caucasian women (Alderman et al., 2009). In

an effort to address this desire, we developed a community based health aware-

ness symposium centered on breast reconstruction directed at women of color in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In this study, we present the results of an analysis of survey responses before

and after lectures on breast cancer screening, treatment, surgical management

and reconstruction options and patient testimonials. The overall uncertainty

noted on all pre-symposium survey responses was fairly striking, with large per-

centages of participants responding, “I don’t know” to the presented questions.

This is even more alarming given that 46% of the symposium participates re-

ported having a college degree or higher. This highlights the fact that even with-

in well-educated groups, knowledge of breast reconstruction may remain poor.

Overall, the percentage of correct responses for all survey questions increased on

the post-symposium survey. With the exception of questions with greater than

60% correct responses in the pre symposium survey, there were statistically sig-

nificant increases in the percentage of correct responses when comparing pre

and post-symposium surveys. This suggests that as intended, the symposium

served to increase knowledge in areas where significant deficiencies initially ex-

isted. Survey questions that touched on breast cancer diagnosis, treatment and

spread (Questions 10 to 14) had the highest number of correct responses in the

pre-symposium (69.8% to 73%). This is unsurprising as breast cancer awareness

rightfully continues to remain at the forefront of discussions amongst healthcare

providers and the general public.

A more in-depth evaluation of the questions with the lowest initial scores

helps identify specific topics that can become the focus of future interventions.

Two of the three questions with the lowest percentage of correct responses

(Questions 8 and 9) in the pre-symposium survey, focused on the safety of im-

plant-based reconstruction and its implication on cancer spread. Prior to the

symposium, less than a fifth of participants believed that silicone implants were

as safe as saline implants, while only 36.5% of participants understood that im-

plant rupture could not cause cancer. Comprehension of both questions in-

creased significantly after the symposium to 66.7% and 71.4%, respectively. In-

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 645 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

surance coverage of breast reconstruction appears to represent another area of

knowledge deficit to be addressed, with 54% of participants unaware of insur-

ance coverage of breast reconstruction and 71.4% unaware of insurance coverage

of contralateral balancing procedures prior to symposium. As expected, these

numbers improved significantly after the educational sessions. With the intro-

duction of The Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act 20 years ago, one would

expect knowledge of its benefits to be more ubiquitous. Nevertheless, the

thought of paying out of pocket for a procedure that a patient might incorrectly

assume would be considered cosmetic could manifest as a major deterrent to ac-

tively seeking additional information about reconstruction. Providing assurance

of insurance coverage of reconstruction as early as possible in the course of a pa-

tient interaction should become an imperative of the diagnosing physician, sur-

gical oncologists, and consulting plastic surgeon.

While the decision to pursue breast reconstruction after mastectomy remains

a personal choice, the counsel of physicians, previous patients, family and

friends can play a significant role. A documented discussion of reconstructive

surgery with a physician has been reported to be the greatest predictor of a pa-

tient undergoing breast reconstruction (Greenberg et al., 2008). We found that

81.8% of the women in our study who underwent breast reconstruction had

discussions about reconstruction with their doctors prior to initiating oncologic

treatment. Almost half of those undergoing reconstruction also had conversa-

tions with family and friends before making their decision. Similarly, in a survey

based study of patient motivations for choosing post-mastectomy breast recon-

struction, Duggal et al. noted that 51.6% of patients reported that they were

urged by their referring physician to consider reconstruction. 58% of their study

participants also discussed the surgery with other breast cancer patients prior to

their decision (Duggal et al., 2013). A few studies have explored the larger effect

of these individual discussions on existing disparities in reconstruction. Mah-

moudi et al. sought to determine whether the 2011 New York legislation man-

dating physicians to communicate about breast reconstruction with their pa-

tients undergoing mastectomy would be associated with reduced racial/ethnic

disparities in immediate post mastectomy breast reconstruction (Mahmoudi et

al., 2017). They found that introduction of the legislature was associated with a

reduction in disparities in immediate breast reconstruction rates by 9% between

Hispanic and white patients and by 13% between other minority groups and

white patients. Although the reduction in disparity did not reach statistical sig-

nificance in African American women, the study suggests that communication

on the part of the physician can have large-scale impact on existing disparities.

Our symposium not only increased breast reconstruction awareness and overall

health literacy but also provided a new avenue to facilitate these patient-surgeon

conversations. Furthermore, it created the opportunity for participants to inte-

ract with other patients who have undergone reconstruction.

Health education programs such as the one presented in this study represent a

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 646 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

continuously evolving process. The information disseminated to the community

must change to reflect new scientific discoveries and growing medical know-

ledge. One of the survey questions touched on the equivalent safety of silicone

and saline implants. This could be considered an over-simplification of a re-

cently more nuanced topic. In the light of more convincing literature and FDA

warning about the association of textured silicone implants with anaplastic large

call lymphoma (ALCL), future symposium lectures and survey question will re-

flect this distinction (Doren et al., 2017; Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic

Large Cell Lymphoma, 2018).

5. Limitations

Admittedly, the conclusions and generalizability of this study are limited by the

small sample size. The target audience of the symposium was women of color in

West Philadelphia that were interested in learning more about breast cancer and

breast reconstruction. This would include both women that personally were di-

agnosed with breast cancer at one point in their life and those that were not. If

we were solely targeting breast cancer survivors, seeking more specific informa-

tion from them regarding their type of cancer, stage at diagnosis, laterality, etc.

would have been prudent and likely impact their questionnaire responses. How-

ever, our intent was to be more general to the community and limit intrusive-

ness. Additionally the survey was not validated prior to use. With these limita-

tions in mind, we believe that our methods and findings can serve as a guide for

the development of similar community based educational programs. This study

also highlights areas of deficiencies that can be targeted in individual patient in-

teractions and larger scale community based events. Due to the overwhelmingly

positive feedback from participants, we plan to continue the symposium as an

annual educational event with the hopes that it will have a larger impact on the

existing disparity in breast reconstruction.

6. Conclusion

The etiology of the observed disparity in breast reconstruction rates between

women of color and Caucasian women is complex and multifactorial. Noting

that health literacy and awareness are critical to a patient’s decision-making

process about their diagnosis and treatment, this study demonstrates that tar-

geted community based educational programs can improve awareness about

breast reconstruction.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Plastic Surgery Foundation as they provided

funding for this community-based event through an awareness grant. We would

also like to thank the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center’s Of-

fice of Diversity, Ms. Brenda Bryant, Dr. Robyn Broach, Dr. Rose Mustafa, Ms.

Traci Smith, Ms. Tawana Reynolds, and Ms. Amy Kleger for their contributions

to the symposium.

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 647 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

Financial Disclosure Statement

The authors listed above have no financial disclosures. A Plastic Surgery Foun-

dation grant awarded to the senior author supported the study in its entirety.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this pa-

per.

References

(2018). Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma.

https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandPro

sthetics/BreastImplants/ucm239995.htm

(2018). Breast Reconstruction Awareness Campaign. http://www.breastreconusa.org

(2018). Breast Reconstruction Awareness: BRA Day. http://www.bra-day.com

Alderman, A. K., Hawley, S. T., Janz, N. K. et al. (2009). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in

the Use of Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction: Results from a Population-Based

Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 5325-5330.

https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2455

Butler, P. D., Familusi, O., Serletti, J. M., & Fox, J. P. (2017). Influence of Race, Insurance

Status, and Geographic Access to Plastic Surgeons on Immediate Breast Reconstruction

Rates. The American Journal of Surgery, 215, 987-994.

Butler, P. D., Nelson, J. A., Fischer, J. P. et al. (2016). Racial and Age Disparities Persist in

Immediate Breast Reconstruction: An Updated Analysis of 48, 564 Patients from the

2005 to 2011 American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement

Program Data Sets. The American Journal of Surgery, 212, 96-101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.025

Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

(2018). Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act.

https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/w

hcra_factsheet.html

Doren, E. L., Miranda, R. N., Selber, J. C. et al. (2017). U.S. Epidemiology of Breast Im-

plant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery,

139, 1042-1050. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003282

Duggal, C. S., Metcalfe, D., Sackeyfio, R., Carlson, G. W., & Losken, A. (2013). Patient

Motivations for Choosing Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. Annals of Plastic

Surgery, 70, 574-580. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182851052

Eltahir, Y., Werners, L. L., Dreise, M. M. et al. (2013). Quality-of-Life Outcomes between

Mastectomy Alone and Breast Reconstruction: Comparison of Patient-Reported

BREAST-Q and Other Health-Related Quality-of-Life Measures. Plastic and Recon-

structive Surgery, 132, 201e-209e.

Fanakidou, I., Zyga, S., Alikari, V., Tsironi, M., Stathoulis, J., & Theofilou, P. (2018).

Mental Health, Loneliness, and Illness Perception Outcomes in Quality of Life among

Young Breast Cancer Patients after Mastectomy: The Role of Breast Reconstruction.

Quality of Life Research, 27, 539-543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1735-x

Greenberg, C. C., Schneider, E. C., Lipsitz, S. R. et al. (2008). Do Variations in Provider

Discussions Explain Socioeconomic Disparities in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruc-

tion? Journal of The American College of Surgeons, 206, 605-615.

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 648 Creative Education

O. Familusi et al.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.11.017

Haider, A. H., Dankwa-Mullan, I., Maragh-Bass, A. C. et al. (2016). Setting a National

Agenda for Surgical Disparities Research: Recommendations from the National Insti-

tutes of Health and American College of Surgeons Summit. JAMA Surgery, 151,

554-563. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0014

Hempstead, B., Green, C., Briant, K. J., Thompson, B., & Molina, Y. (2018). Community

Empowerment Partners (CEPs): A Breast Health Education Program for Afri-

can-American Women. Journal of Community Health, 43, 833-841.

Hoffman, R. L., Bryant, B., Allen, S. R., Lee, M. K., Aarons, C. B., & Kelz, R. R. (2016).

Using Community Outreach to Explore Health-Related Beliefs and Improve Surge-

on-Patient Engagement. Journal of Surgical Research, 206, 411-417.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2016.08.058

Hurd, T. C., Muti, P., Erwin, D. O., & Womack, S. (2003). An Evaluation of the Integra-

tion of Non-Traditional Learning Tools into a Community Based Breast and Cervical

Cancer Education Program: The Witness Project of Buffalo. BMC Cancer, 3, 18.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-3-18

Lebo, P. B., Quehenberger, F., Kamolz, L. P., & Lumenta, D. B. (2015). The Angelina Ef-

fect Revisited: Exploring a Media-Related Impact on Public Awareness. Cancer, 121,

3959-3964. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29461

Mahmoudi, E., Lu, Y., Metz, A. K., Momoh, A. O., & Chung, K. C. (2017). Association of

a Policy Mandating Physician-Patient Communication with Racial/Ethnic Disparities

in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. JAMA Surgery, 152, 775-783.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0921

Nelson, J. A., Nelson, P., Tchou, J., Serletti, J. M., & Wu, L. C. (2012). The Ethnic Divide

in Breast Reconstruction: A Review of the Current Literature and Directions for Future

Research. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 38, 362-367.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.12.011

Santos, S. L., Tagai, E. K., Scheirer, M. A. et al. (2017). Adoption, Reach, and Implemen-

tation of a Cancer Education Intervention in African American Churches. Implemen-

tation Science, 12, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0566-z

Tseng, J. F., Kronowitz, S. J., Sun, C. C. et al. (2004). The Effect of Ethnicity on Immediate

Reconstruction Rates after Mastectomy for Breast Cancer. Cancer, 101, 1514-1523.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20529

DOI: 10.4236/ce.2019.104046 649 Creative Education

You might also like

- BITSEA Brief Guide For Professionals: What Is The BITSEA?Document4 pagesBITSEA Brief Guide For Professionals: What Is The BITSEA?Mihaela GrigoroiuNo ratings yet

- Basic Incident Command System Course: Activity Packet For TraineesDocument12 pagesBasic Incident Command System Course: Activity Packet For TraineesPELIGRO RAMIENo ratings yet

- (Brandao de Carvalho, Joaquim) Lenition and FortitionDocument607 pages(Brandao de Carvalho, Joaquim) Lenition and FortitionLevente JambrikNo ratings yet

- Current Issues in Nursing EducationDocument12 pagesCurrent Issues in Nursing EducationMhel Es QuiadNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing The Health Seeking Behaviors of Wo - 2021 - International JoDocument9 pagesFactors Influencing The Health Seeking Behaviors of Wo - 2021 - International JoRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Preventive Medicine: Shristi Bhochhibhoya, Page D. Dobbs, Sarah B. ManessDocument9 pagesPreventive Medicine: Shristi Bhochhibhoya, Page D. Dobbs, Sarah B. ManessRolando NavarroNo ratings yet

- Falope RM Chapter 1 (18518)Document7 pagesFalope RM Chapter 1 (18518)falopetaiwo.12No ratings yet

- Advancing Genetic Nursing Knowledge 2004 Nursing OutlookDocument7 pagesAdvancing Genetic Nursing Knowledge 2004 Nursing OutlookSeeta NanooNo ratings yet

- Ca MamaeDocument7 pagesCa MamaeAnonymous vkq7UwNo ratings yet

- Foster2018 PDFDocument1 pageFoster2018 PDFFake_Me_No ratings yet

- The International Glossary On Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017Document14 pagesThe International Glossary On Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017Zurya UdayanaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2414644721000877 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2414644721000877 MainSome LaNo ratings yet

- IDocument2 pagesIAllysa Megan OrpillaNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer ReflectionDocument4 pagesBreast Cancer ReflectionCAJES NOLINo ratings yet

- Enc 1101 - Project 2 Research Proposal and Annotated Bibliography - Spring 2024Document5 pagesEnc 1101 - Project 2 Research Proposal and Annotated Bibliography - Spring 2024api-742553212No ratings yet

- Gakunga 2019Document8 pagesGakunga 2019FaidurrahmanNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer Knowledge Among College Students Justice King Vidourek Merianos 2018Document10 pagesBreast Cancer Knowledge Among College Students Justice King Vidourek Merianos 2018Marc BantilanNo ratings yet

- Oncology Nurse Managers' Perceptions of Palliative Care and End-of-Life CommunicationDocument13 pagesOncology Nurse Managers' Perceptions of Palliative Care and End-of-Life CommunicationRatih puspita DewiNo ratings yet

- Breast ThesisDocument4 pagesBreast Thesisafjrpomoe100% (2)

- Breast Cancer Awareness Among Health ProfessionalsDocument3 pagesBreast Cancer Awareness Among Health ProfessionalsWac GunarathnaNo ratings yet

- Obesity and Breast Reconstruction: Complications and Patient-Reported Outcomes in A Multicenter, Prospective StudyDocument10 pagesObesity and Breast Reconstruction: Complications and Patient-Reported Outcomes in A Multicenter, Prospective StudyMehmet SürmeliNo ratings yet

- Awarness About Breast CancerDocument4 pagesAwarness About Breast CancerliaahlanNo ratings yet

- Patient Education and Counseling: Joelle I. Rosser, Betty Njoroge, Megan J. HuchkoDocument6 pagesPatient Education and Counseling: Joelle I. Rosser, Betty Njoroge, Megan J. HuchkoTrysna Ayu SukardiNo ratings yet

- Research ReportDocument13 pagesResearch Reportapi-662910690No ratings yet

- FTP PDFDocument5 pagesFTP PDFRismayantiNo ratings yet

- EJ1078866Document12 pagesEJ1078866valentinasecivirNo ratings yet

- Clinical Oncology: World Journal ofDocument13 pagesClinical Oncology: World Journal ofMATEJ MAMICNo ratings yet

- Oalibj 2020102215471650Document19 pagesOalibj 2020102215471650Balali GadafiNo ratings yet

- Use of and Attitudes and Knowledge About Pap Smears Among Women in KuwaitDocument18 pagesUse of and Attitudes and Knowledge About Pap Smears Among Women in KuwaitHanisha EricaNo ratings yet

- Nursing CourseDocument8 pagesNursing Coursepatel ravirajNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Breast Self Examination ResearchDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Breast Self Examination ResearchaflsigakfNo ratings yet

- POSITIVEDocument12 pagesPOSITIVEtabaresgonzaloNo ratings yet

- Maternity MainDocument13 pagesMaternity Mainbayu purnomoNo ratings yet

- Family Support and Self-Esteem of Patient With Breast CancerDocument5 pagesFamily Support and Self-Esteem of Patient With Breast CancerDean Rex Azriel TelaumbanuaNo ratings yet

- Cut Off2Document15 pagesCut Off2Odiyana Prayoga GriadhiNo ratings yet

- Information Needs of Women With Breast Cancer: A Review of The LiteratureDocument16 pagesInformation Needs of Women With Breast Cancer: A Review of The LiteratureHina SardarNo ratings yet

- The Role of Nursing in Cervical Cancer Prevention and TreatmentDocument5 pagesThe Role of Nursing in Cervical Cancer Prevention and TreatmentLytiana WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument7 pages1 PDFSarah AryaNo ratings yet

- A Study To Assess The Knowledge Regarding Cervical Cancer Among Women in Selected Community Setting, ChennaiDocument3 pagesA Study To Assess The Knowledge Regarding Cervical Cancer Among Women in Selected Community Setting, ChennaiEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Decision Aids On Breast ConserDocument15 pagesDecision Aids On Breast Consersatria divaNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0253373Document17 pagesJournal Pone 0253373ElormNo ratings yet

- The Role and Contribution of Psychology Inthe Navigation of Oncology PatientsDocument6 pagesThe Role and Contribution of Psychology Inthe Navigation of Oncology PatientsSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- BreastfeedDocument5 pagesBreastfeedBetHsy Pascua100% (1)

- A Protocol For A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of A Self Help Psycho Education Programme To Reduce Diagnosis Delay in Women With Breast Cancer Symptoms in IndonesiaDocument8 pagesA Protocol For A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of A Self Help Psycho Education Programme To Reduce Diagnosis Delay in Women With Breast Cancer Symptoms in Indonesiaflorentina dianNo ratings yet

- 503 837 1 PBDocument14 pages503 837 1 PB5m7m2c2kryNo ratings yet

- Rosen's Breast Pathology IntroductionDocument18 pagesRosen's Breast Pathology IntroductionyoussNo ratings yet

- Summary of Third Expert Report 2018Document116 pagesSummary of Third Expert Report 2018Diego12001No ratings yet

- Sobrevivientes Del Cancer GinecológicoDocument10 pagesSobrevivientes Del Cancer GinecológicoMIGUEL MORENONo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Cervical Cancer and Screening Among Women Visiting Primary Health Care Centres in BahrainDocument6 pagesKnowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Cervical Cancer and Screening Among Women Visiting Primary Health Care Centres in BahrainAnonymous N74eaOhdfkNo ratings yet

- Developing A Web-Based Shared Decision-Making Tool For Fertility Preservation Among Reproductive-Age Women With Breast CancerDocument10 pagesDeveloping A Web-Based Shared Decision-Making Tool For Fertility Preservation Among Reproductive-Age Women With Breast Cancer郭竹瑩No ratings yet

- Research Project 1Document9 pagesResearch Project 1Sangeeta SahaNo ratings yet

- Health Professionals ' Views On Maternity Care For Women With Physical Disabilities: A Qualitative StudyDocument11 pagesHealth Professionals ' Views On Maternity Care For Women With Physical Disabilities: A Qualitative StudyNabilaNo ratings yet

- Mojwh 08 00237Document9 pagesMojwh 08 00237EndalkNo ratings yet

- Thesis Cancer HospitalDocument7 pagesThesis Cancer HospitalCollegePaperWritingServiceCanada100% (2)

- Literature Review On Birth PreparednessDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Birth Preparednessmgrekccnd100% (1)

- Pathogenesis Prevention Diagnosis and Treatment ofDocument18 pagesPathogenesis Prevention Diagnosis and Treatment ofMubarak Abubakar yaroNo ratings yet

- A Review of 10 Years of Vasectomy Programming andDocument14 pagesA Review of 10 Years of Vasectomy Programming andtashaNo ratings yet

- Guideline 2013 Breast Recon Expanders ImplantsDocument23 pagesGuideline 2013 Breast Recon Expanders ImplantsBogdan TudorNo ratings yet

- Improving Mammography ScreeningDocument8 pagesImproving Mammography ScreeningsylviaramisNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practice in Maternal and Child HealthDocument1 pageEvidence-Based Practice in Maternal and Child HealthKaycee JoyNo ratings yet

- Oup Accepted Manuscript 2018Document7 pagesOup Accepted Manuscript 2018FaidurrahmanNo ratings yet

- FTP Three-Year Analysis of Treatment Efficacy, Cosmesis and ToxicityDocument9 pagesFTP Three-Year Analysis of Treatment Efficacy, Cosmesis and ToxicitySara SánNo ratings yet

- 5223-Article Text-23037-2-10-20200913Document10 pages5223-Article Text-23037-2-10-20200913m.sandra12340No ratings yet

- Preconception Health and Care: A Life Course ApproachFrom EverandPreconception Health and Care: A Life Course ApproachJill ShaweNo ratings yet

- Ijams: Parent-Assisted Learning Awareness and Performance of The Grade 7 Students in EnglishDocument12 pagesIjams: Parent-Assisted Learning Awareness and Performance of The Grade 7 Students in EnglishLeonilo B CapulsoNo ratings yet

- 10-12-2023 - CTM-08 - Mains ResultsDocument21 pages10-12-2023 - CTM-08 - Mains ResultsinfinitylearmNo ratings yet

- Student Name 1st Aid 2023 Term 3Document18 pagesStudent Name 1st Aid 2023 Term 3vNo ratings yet

- First City Providential CollegeDocument4 pagesFirst City Providential Collegerommel rentoriaNo ratings yet

- Cs1020software Quality ManagementDocument1 pageCs1020software Quality Managementimmu747No ratings yet

- The Open Group IT Architect Certification: Certification Package Level 2: Master Certified IT Architect October 03, 2008 Revision 2.3Document48 pagesThe Open Group IT Architect Certification: Certification Package Level 2: Master Certified IT Architect October 03, 2008 Revision 2.3Rogerio CanoNo ratings yet

- 5CQBT05 Dang Thao Phi Vietnamese and English Verb PhrasesDocument17 pages5CQBT05 Dang Thao Phi Vietnamese and English Verb PhrasesBenjamin FranklinNo ratings yet

- Jira Ticket Templates-300124-152841Document5 pagesJira Ticket Templates-300124-152841Thu NguyenNo ratings yet

- MBA Project Guidelines-2021Document6 pagesMBA Project Guidelines-2021Madhuri BhanuNo ratings yet

- Polyglot Discord Server - Effective Learning PDFDocument8 pagesPolyglot Discord Server - Effective Learning PDFPetr BlinnikovNo ratings yet

- Brief Summary of Liminal Thinking 1 0Document7 pagesBrief Summary of Liminal Thinking 1 0Mayank SahuNo ratings yet

- Artikel 18 Kbat PecahanDocument5 pagesArtikel 18 Kbat PecahanSilvens Siga SilvesterNo ratings yet

- Dr. Kirk Kelly Cover Letter and Resume For Hamilton County School Superintendent PositionDocument2 pagesDr. Kirk Kelly Cover Letter and Resume For Hamilton County School Superintendent PositionNewsChannel 9 StaffNo ratings yet

- Senior High RoadmapDocument2 pagesSenior High Roadmapmikhael SantosNo ratings yet

- Mid Course WorkDocument112 pagesMid Course WorkT SeriesNo ratings yet

- Preston Dunlap - Sales Marketing Resume 10 23 15Document1 pagePreston Dunlap - Sales Marketing Resume 10 23 15api-299655525No ratings yet

- Introductionto RubricsDocument21 pagesIntroductionto Rubricsaa256850100% (1)

- SRC Guide 06Document192 pagesSRC Guide 06Joe EvansNo ratings yet

- Grad BulletinDocument164 pagesGrad BulletinPaulo AguilarNo ratings yet

- 2012.4 Comm Theory Scrapbook Final ProjectDocument13 pages2012.4 Comm Theory Scrapbook Final ProjectLoriAveryNo ratings yet

- SMTDocument42 pagesSMTMirjana PrekovicNo ratings yet

- Tesol Technology StandardsDocument15 pagesTesol Technology StandardsJim CabezasNo ratings yet

- Role of NursesDocument2 pagesRole of NursesShaira GumaruNo ratings yet

- 8th Karmapa, Mikyo Dorje, Life and WorksDocument536 pages8th Karmapa, Mikyo Dorje, Life and WorksSergey Sergey100% (4)

- 02 Course Structure - Fea - 19-20 - VelDocument6 pages02 Course Structure - Fea - 19-20 - Velrajamanickam sNo ratings yet

- 9th Form WritingDocument1 page9th Form WritingЧебан Агрипина 9-ВNo ratings yet