Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bernasconi Supplement

Uploaded by

juckballeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bernasconi Supplement

Uploaded by

juckballeCopyright:

Available Formats

3 Supplement

Robert Bernasconi

In Of Grammatology Derrida took up the term supplément from his

reading of both Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Claude Lévi-Strauss and used

it to formulate what he called “the logic of supplementarity” (G: 144–45).

Derrida returned to Lévi-Strauss’s use of the word “supplement” in

“Structure, Sign and Play” (WD: 289) and in Given Time (GT: 66–77),

but I will focus here on Derrida’s reading of this word in Rousseau’s

Confessions, Discourse on the Origin and Foundation of Inequality

among Men, and Essay on the Origin of Languages because his reading

of Rousseau has proved so powerful and because the logic of supple-

mentarity is better illustrated than generalised.

As Derrida observed, Rousseau in these works employed binary

oppositions: nature versus society, passion versus need, south versus

north, and, most significantly for Derrida in the late 1960s, speech versus

writing. In the course of declaring these oppositions Rousseau can be

found writing the ambiguous term supplément and its cognates into his

narratives. The supplement is an addition from the outside, but it can

also be understood as supplying what is missing and in this way is

already inscribed within that to which it is added. In this way the word,

“supplement” seems to account for “the strange unity” of two gestures:

“on the side of experience, a recourse to literature as appropriation of

presence, that is to say, … of Nature; on the side of theory, an indict-

ment against the negativity of the letter, in which must be read the

degeneracy of culture and the disruption of the community” (G: 144).

To the extent that Derrida presents the supplement as the unity of two

gestures it is not yet fully radicalised. One can find in other authors’ for-

mulations that suggest a notion of supplementarity to the extent that what

stands first and what follows it can vary according to one’s perspective.

One might say that the so-called Cartesian circle where the order of rea-

sons is different from the order of being has that same structure. Or one

might point to Georges Canguilhem’s formulation, articulated at the same

20 Robert Bernasconi

time as that Derrida was writing Of Grammatology, the historical ante-

riority of the future abnormal, while logically second, is existentially prior

(Canguilhem 1991: 243). But Derrida’s claim goes beyond the idea that

these two meanings of the supplement can be seen to function together in

Rousseau’s texts and elsewhere in spite of their apparent opposition.

When Derrida announced that “the logic of supplementarity,” rather

than the logic of non-contradiction, can be said to regulate or organise

Rousseau’s texts, he was introducing a new way of reading texts that con-

stituted a major departure from what had gone before. At this time other

philosophers still insisted on reading the canonical texts of philosophy

according to the imperative that contradiction cannot be tolerated, with the

consequence that there was a hermeneutical imperative to do whatever one

could to reunite seemingly inconsistent claims. Derrida responded to this

imperative by showing how the supplement allows Rousseau – and us – to

say the contrary without contradiction (G: 179; Bernasconi 1992: 143–44).

Identifying these twin gestures within Rousseau’s texts gave rise to

what came to be called “double reading.” The practice of double reading

as it relates to the supplement can best be illustrated by following the two

tracks that Derrida identifies in Rousseau’s texts. To begin with, Rous-

seau’s Essay on the Origin of Languages argues that the origin of (spoken)

language is in the South. Writing comes second and has its origin in the

North. But Derrida observes that in the course of giving this description

Rousseau refers to gestures joined to speech (Rousseau 1992: 31). Derrida

comments: “Gesture, is here an adjunct to speech, but this adjunct is not a

supplementing by artifice, it is a recourse to a more natural, more

expressive, more immediate sign” (G: 235) as when one can simply point

at an object and there is no need to speak (Rousseau 1998: 292). Speech,

far from being the original, is “a substitute for gesture” (G: 235). How-

ever, insofar as gesture can be seen as a form of writing, then the apparent

priority of speech over writing is put into question. Writing as an addition

(which is originally conceived as a simple exterior to speech, substituting

itself for it), comes to be seen as anterior to speech and in a way integral

to it. In other words, that something can be added to what is initially

thought of as in and of itself complete, and is presented as an origin,

reveals that the lack in sense precedes the origin and contaminates it.

The priority of speech is what Rousseau declares, corresponding to

what he wants or desires which, according to Derrida, is full presence:

but, as we have seen, Rousseau’s narrative tells a different story. The

declarations conflict with the descriptions. Derrida shows, however, that

their interrelation is regulated, thereby establishing that the two readings

are not independent and ultimately cannot be separated. They belong

together “in one divided but coherent meaning” (G: 132). They

Supplement 21

constitute “structural poles rather than natural and fixed points

of reference” (G: 216). In this way the second reading can be said to

“supplement” the first, as writing supplements speech. And it is “unde-

cidable” which meaning dominates the text.

There is another dimension to this reading. As we saw, for Rousseau,

speech, and thus the South, initially represents presence, before it emer-

ges that sometimes gesture performs this function better (G: 237). This

ties Derrida’s reading of Rousseau to Heidegger’s account of Western

metaphysics in terms of the priority of presence. The deconstruction of

Rousseau thus belongs to the deconstruction of Western metaphysics.

Rousseau’s text, on Derrida’s reading, both exhibits Western meta-

physics and at the same time undercuts it. Or, better, the text decon-

structs itself. Just as Rousseau wants to mark a full presence but finds

that it has never existed, so Derrida finds that there never was such a

thing as Western metaphysics as such (Bernasconi 1989: 246).

Derrida does not explore in the same detail how the same logic of

supplementarity governs Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and Foun-

dation of Inequality among Men but it is not hard to reconstruct it on

the basis of what Derrida says about the Essay on the Origin of Lan-

guages. In the Essay Rousseau sets out to explain the break with

nature – nature’s departure from itself – solely on the basis of “natural

causes” (Rousseau 1998: 289). It is the same in the Second Discourse,

when it comes to explaining how one could leave the state of nature.

The basis for the movement beyond nature into society must already

in some way be implanted within nature, thereby complicating the

notion of nature, which is no longer to be seen as the full presence of an

origin but as a lack that could in a different idiom be located beyond

being as presence. This is why Rousseau can say that the state of nature

no longer exists, perhaps never existed, and probably never will exist

(Rousseau 1991: 13). Nevertheless this lack controls all discourse about

the society, which is produced to supplement what is lacking there. In

Rousseau’s essays on both the origin of inequality and the origin of

languages, the powerful notion of origin takes on another character such

that, as Derrida puts it elsewhere, “the movement of supplementarity” is

“the movement of play, permitted by the lack or absence of a center or

origin” (WD: 289).

Just as in Rousseau that which is beyond nature and which thereby

makes up for what is lacking in nature is implanted within nature, so

that nature is not the full presence that was sought, so albeit in a slightly

different fashion, what is beyond being in Plato necessarily governs that

absent origin by which it is supposed to be ordered. Derrida wrote in

“Plato’s Pharmacy”: “The absolute invisibility of the origin of the

22 Robert Bernasconi

visible, of the good-sun-father-capital, the unattainment of presence or

beingness in any form, the whole surplus Plato calls epekeina tes ousias

(beyond beingness or presence), gives rise to a structure of replacements

(suppléances) such that all presences will be supplements substituted for

the absent origin, and all differences, within the system of presence, will

be the irreducible effect of what remains epekeina tes ousias” (D: 167).

This shows just how far Derrida is from the straightforward exploration

of the ambiguity of the word pharmakon as both remedy and poison

that is sometimes attributed to him. He located the logic of supple-

mentarity in still other texts and contexts. So, for example, around the

same time that he published Of Grammatology he wrote Speech and

Phenomena in which he described the relation of indication and expres-

sion in Husserl’s Logical Investigations: “If indication is not added onto

expression which is not added onto sense, we can nevertheless speak in

regard to them, about an originary ‘supplement’: their additon comes to

make up for a deficiency, it comes to compensate for a primordial non-

self-presence” (SP: 74). All the details of Derrida’s argument cannot be

rehearsed here, but it culminates in the now familiar claim that indica-

tion dictates expression on the grounds that writing cannot be added to

speech “because, as soon as speech awakens, writing has doubled it by

animating it” (SP: 83).

One of Derrida’s clearest explications of the logic of supplementarity is

in his reading of Condillac’s Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge in

The Archeology of the Frivolous from 1973. He finds in Condillac’s dis-

cussion of the attempt to create a language for a science of economics,

that there is a need to supplement our speaking and writing (Condillac

1795: iii). With reference to Condillac’s discussion of how the defect of

language might be addressed by a certain kind of supplementing that

refers to an anteriority with reference to which there is something lacking.

Derrida argues that there is need for a second sense of the supplement:

“But what is necessary – what is lacking – also presents itself as a surplus,

an overabundance of value, a frivolous futility that would have to be

subtracted, although it makes all commerce possible” (AF: 101). In other

words, as the present comes to present itself the necessity of what is

lacking is produced as a certain frivolity. Or, as he explained in “Freud

and the Scene of Writing,” the supplement is “added as a plenitude to a

plenitude” and for this reason he could insist that it equally compensates

for a lack” (WD: 212). It is in keeping with this insight that Derrida

insisted both that no ontology could think the operation of the supplement

(G: 314) and, at the same time, the time of the closure of philosophy, that

the logic of supplementarity imposes itself on us in our reading of the

texts from the history of Western metaphysics.

4 Suspension

Anne C. McCarthy

State of Suspension

“ … the state of suspension in which it’s over—and over again, and

you’ll never have done with that suspension itself … ” (LO: 63). Take

this utterance, for the moment, as something bracketed, cited in the

fullest Derridean sense of the term, surrounded on both sides by ellipses

(that is, by suspension points or points de suspension), lifted from a text

that begins, as Derrida’s often do, by suspending the question it sets out

to address, pausing to hold it up, to hold us up, in a moment of con-

templation. “over—and over again”: the pause initiates the possibility of

the endless repetition of endings; “you’ll never have done with that sus-

pension itself”—suspension resists the demand for closure, for transpar-

ency. All it can reveal to the gaze of authority is its own essential

equivocation, its own being-otherwise.

What would it mean to suspend suspension, to pause the pause, to

interrupt interruption and thereby hold it up, examine it? Fixation and

contemplation, punishment and mitigation, an inactivity actively main-

tained: the paradoxical, aberrant quality of suspension reveals itself at

every turn. Attempts to define it often draw upon a kind of internal

catachresis that keeps it from fully coinciding with itself, manifesting in

contradictory phrases: passive activity, active passivity. Fading into the

background, it calls attention to the attenuated presence of what it sus-

pends. Thus the suspension of a privilege makes us realise what we have

lost, the suspension of judgement may be taken as an indicator of the

soundness of that judgement, and the request that an audience suspend

its disbelief causes that audience to anticipate the unbelievable.

Though we customarily speak of uncertainty as a lack or privation,

suspension enables uncertainty to appear as something other than a

negative form of knowing. It provides a way of avoiding typical respon-

ses to that uncertainty, such as dismissing what is not known as being

You might also like

- Derrida's Concepts of Différance, Dissemination and DeconstructionDocument7 pagesDerrida's Concepts of Différance, Dissemination and DeconstructionAisha RahatNo ratings yet

- Derrida's Reading of Saussure Challenged in New Directions Conference PaperDocument13 pagesDerrida's Reading of Saussure Challenged in New Directions Conference PaperRoswitha GeyssNo ratings yet

- Meaning in Grammatology and SemiologyDocument6 pagesMeaning in Grammatology and SemiologyRandolph DibleNo ratings yet

- Firnand de Saussure About StructuralismDocument3 pagesFirnand de Saussure About StructuralismAbdelghani BentalebNo ratings yet

- DeconstructionismDocument37 pagesDeconstructionismLOVELY REVANO100% (1)

- Deconstruction 1Document4 pagesDeconstruction 1ayeshaminahil78No ratings yet

- Post-Structuralism and Deconstruction ExplainedDocument6 pagesPost-Structuralism and Deconstruction ExplainedDoris GeorgiaNo ratings yet

- On Derridean Différance - UsiefDocument16 pagesOn Derridean Différance - UsiefS JEROME 2070505No ratings yet

- Derrida and Oralcy: Grammatology Revisited: Christopher NorrisDocument22 pagesDerrida and Oralcy: Grammatology Revisited: Christopher NorrisShineNo ratings yet

- Tropiques), and Philosophy (Rousseau's Essay On The Origin of Languages)Document3 pagesTropiques), and Philosophy (Rousseau's Essay On The Origin of Languages)satayjit4nairNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument4 pagesAssignmentDivya KhasaNo ratings yet

- Der Rid ADocument5 pagesDer Rid AAnuraag BaruahNo ratings yet

- The Deconstructive AngelDocument2 pagesThe Deconstructive AngelBarnali SahaNo ratings yet

- The Trace of TransferenceDocument18 pagesThe Trace of TransferenceElchoNo ratings yet

- The Literal and Metaphorical in LanguageDocument5 pagesThe Literal and Metaphorical in LanguageJohn MarrisNo ratings yet

- "Voice" and "Address" in Literary Theory: Oral Tradition, 2/1 (1987) : 214-30Document17 pages"Voice" and "Address" in Literary Theory: Oral Tradition, 2/1 (1987) : 214-30CarmenFloriPopescuNo ratings yet

- 2 Bbau Group (A)Document6 pages2 Bbau Group (A)Roy CardenasNo ratings yet

- DA Carson On Postmodernism - Critique by J GarverDocument5 pagesDA Carson On Postmodernism - Critique by J GarverMonica Coralia TifreaNo ratings yet

- DerridaDocument7 pagesDerridaUmesh KaisthaNo ratings yet

- Deconstruction and Taoism Reconsidered Fu Hungchu PDFDocument27 pagesDeconstruction and Taoism Reconsidered Fu Hungchu PDFpobujidaizheNo ratings yet

- Deconstructive Reading of a Poetic WorkDocument12 pagesDeconstructive Reading of a Poetic WorkMary NasrullahNo ratings yet

- Deconstruction and Derrida's Challenge to Binary OppositionsDocument16 pagesDeconstruction and Derrida's Challenge to Binary OppositionsZinya AyazNo ratings yet

- Derrida's Concept of Otherness and DeconstructionDocument7 pagesDerrida's Concept of Otherness and DeconstructionMuhammad SayedNo ratings yet

- The Difference Between External and Internal Aspects of Language SystemsDocument8 pagesThe Difference Between External and Internal Aspects of Language SystemsJordan Thomas MitchellNo ratings yet

- In Other Words, The Gap or Lacuna Between What A Text Means To Say and What It Is Constrained To Mean Creates AporiaDocument1 pageIn Other Words, The Gap or Lacuna Between What A Text Means To Say and What It Is Constrained To Mean Creates AporiaVinaya BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- TraceDocument5 pagesTraceMark EnfingerNo ratings yet

- DeconstructionDocument16 pagesDeconstructionrippvannNo ratings yet

- Study of Post-Modernism and Post-StructuralismDocument3 pagesStudy of Post-Modernism and Post-StructuralismIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- H o W N o T To Read: Derrida On Husserl : Kevin MulliganDocument10 pagesH o W N o T To Read: Derrida On Husserl : Kevin MulliganErvin AlingalanNo ratings yet

- Derrida and NagarjunDocument11 pagesDerrida and NagarjunSiddhartha Singh100% (1)

- The Deconstructive AngelDocument6 pagesThe Deconstructive Angelakashwanjari100% (1)

- Reading Derrida Margins of Philosophy IrDocument4 pagesReading Derrida Margins of Philosophy IrGuillem PujolNo ratings yet

- Understanding As Over-Hearing: Towards A Dialogics of VoiceDocument22 pagesUnderstanding As Over-Hearing: Towards A Dialogics of VoiceaaeeNo ratings yet

- Gerasimos Kakoliris, Derrida's Double Deconstructive Reading: A Contradiction in Terms?Document11 pagesGerasimos Kakoliris, Derrida's Double Deconstructive Reading: A Contradiction in Terms?gkakolirisNo ratings yet

- Binary Oppositions. The Deconstructive Reading of A Text, Then, Is To Show The Logo-CentricityDocument13 pagesBinary Oppositions. The Deconstructive Reading of A Text, Then, Is To Show The Logo-Centricityshadi sabouriNo ratings yet

- DeconstructionDocument2 pagesDeconstructionraofaNo ratings yet

- Deuina-2 1Document19 pagesDeuina-2 1Ira LightmanNo ratings yet

- Bennington Derrida and DeconstructionDocument2 pagesBennington Derrida and Deconstructiona.lionel.blaisNo ratings yet

- Senatore, Mauro - Phenomenology and DeconstructionDocument8 pagesSenatore, Mauro - Phenomenology and DeconstructionTajana KosorNo ratings yet

- Rodolphe Gasché - The 'Violence' of Deconstruction PDFDocument22 pagesRodolphe Gasché - The 'Violence' of Deconstruction PDFManticora VenerabilisNo ratings yet

- On Derrida's Signature, Event, ContextDocument8 pagesOn Derrida's Signature, Event, ContextakansrlNo ratings yet

- Structure Sing and PlayDocument39 pagesStructure Sing and PlayyellowpaddyNo ratings yet

- DeconstructionDocument5 pagesDeconstructionPriyanshu PriyaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 DeconstructionDocument10 pagesChapter 4 DeconstructionatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- S Rider-1998-Avoiding The Subject Part-IIDocument45 pagesS Rider-1998-Avoiding The Subject Part-IIErvin AlingalanNo ratings yet

- Diasporic Gendre RoleDocument17 pagesDiasporic Gendre RoleRamesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Peirce and Derrida: From sign to signDocument14 pagesPeirce and Derrida: From sign to signOtávioNo ratings yet

- Deconstruction TheoryDocument3 pagesDeconstruction Theorydnay danyNo ratings yet

- Derrida and Husserl On Time: Luke FischerDocument14 pagesDerrida and Husserl On Time: Luke FischerErvin AlingalanNo ratings yet

- 50Document9 pages50Mysha ZiaNo ratings yet

- History: Sources of DeconstructionDocument14 pagesHistory: Sources of DeconstructionDipo Rion da OnNo ratings yet

- DeconstructionDocument8 pagesDeconstructionFernando RiusNo ratings yet

- Diane Davis - The Retrait of Rhetoric - Derrida (2024)Document21 pagesDiane Davis - The Retrait of Rhetoric - Derrida (2024)madsleepwalker08No ratings yet

- UTN módulo 7 2024 postructuralism & deconstructionDocument8 pagesUTN módulo 7 2024 postructuralism & deconstructionceciliaturoldoNo ratings yet

- REF Grove Music Online, Deconstruction PDFDocument13 pagesREF Grove Music Online, Deconstruction PDFblahblahNo ratings yet

- Deconstructive Criticism in Sick RoseDocument13 pagesDeconstructive Criticism in Sick RosePeter tola100% (1)

- The Idea of Danger in The SupplementDocument2 pagesThe Idea of Danger in The SupplementDebarshi ArathdarNo ratings yet

- Speech and Phenomena: Husserl Studies 4:45-62 (1987)Document18 pagesSpeech and Phenomena: Husserl Studies 4:45-62 (1987)Ervin AlingalanNo ratings yet

- A Short History of Literary CriticismDocument303 pagesA Short History of Literary CriticismAliney Santos Gallardo100% (2)

- William of ChampeauxDocument26 pagesWilliam of ChampeauxjuckballeNo ratings yet

- Religions 03 00151 PDFDocument12 pagesReligions 03 00151 PDFjasonlustigNo ratings yet

- Poststructuralism: Post-Structuralism Means After Structuralism. However, The Term Also Strongly ImpliesDocument5 pagesPoststructuralism: Post-Structuralism Means After Structuralism. However, The Term Also Strongly ImpliesjuckballeNo ratings yet

- A Specter That Will Not Go AwayDocument5 pagesA Specter That Will Not Go AwayjuckballeNo ratings yet

- A Psychological Inquiry Into TotalitarianismDocument13 pagesA Psychological Inquiry Into TotalitarianismjuckballeNo ratings yet

- A Forgotten GeniusDocument4 pagesA Forgotten GeniusjuckballeNo ratings yet

- A Philosophical AnalysisDocument20 pagesA Philosophical AnalysisjuckballeNo ratings yet

- Adolf Hitler Was A German ManDocument1 pageAdolf Hitler Was A German ManjuckballeNo ratings yet

- Literary Genres: The Classical Epic TraditionDocument2 pagesLiterary Genres: The Classical Epic Traditionliterature loversNo ratings yet

- Day 5 Sundarakanda ParayanamDocument113 pagesDay 5 Sundarakanda ParayanamPrasanth mallavarapuNo ratings yet

- Report in RizalDocument21 pagesReport in RizalJL Dela Cruz NaragNo ratings yet

- Cycle of Fiat Money: An Insight Into Its History and Evolution". She Argues OnDocument2 pagesCycle of Fiat Money: An Insight Into Its History and Evolution". She Argues OnPrasad NeerajNo ratings yet

- Paris Review - The Art of Fiction No. 128Document14 pagesParis Review - The Art of Fiction No. 128manuel.grisaceoNo ratings yet

- Daffodils One PagerDocument3 pagesDaffodils One Pagergunika tanejaNo ratings yet

- Literary Theories UAS Semester Gazal 2020 2021Document4 pagesLiterary Theories UAS Semester Gazal 2020 2021Alham UtamaNo ratings yet

- romeo juliet - student workbook final 1Document22 pagesromeo juliet - student workbook final 1api-583543475No ratings yet

- Stoic BooksDocument11 pagesStoic Booksvortex105100% (1)

- Grade 5 English WritingDocument5 pagesGrade 5 English WritingR-Jhay De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 5 - Urdu and Regional Languages PAKISTAN STUDIESDocument3 pages5 - Urdu and Regional Languages PAKISTAN STUDIESSam ManNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 Present S or C TestDocument2 pagesGrade 7 Present S or C TestghinwaNo ratings yet

- Kapampangan LiteratureDocument6 pagesKapampangan LiteratureFailan Mendez100% (1)

- Hazlitt's Insights on Shakespeare's Plays & CharactersDocument49 pagesHazlitt's Insights on Shakespeare's Plays & CharacterswiweksharmaNo ratings yet

- SWIFT Tale of A TubDocument4 pagesSWIFT Tale of A TubDavidThames123No ratings yet

- Epic Hero Prince Bantugan LessonDocument10 pagesEpic Hero Prince Bantugan LessonCarrion Ella100% (7)

- ROL As Social SatireDocument3 pagesROL As Social SatireElena AiylaNo ratings yet

- If We Must Die by Claude McKayDocument3 pagesIf We Must Die by Claude McKaymishineNo ratings yet

- Polyphemus PDFDocument18 pagesPolyphemus PDFMarcusNo ratings yet

- Eng4u Elements of Short Stories Literary Devices Test1Document2 pagesEng4u Elements of Short Stories Literary Devices Test1Αθηνουλα ΑθηναNo ratings yet

- Ballad of The MoonDocument4 pagesBallad of The MoonveraNo ratings yet

- The PorterDocument2 pagesThe PorterKuldeep MallickNo ratings yet

- Naskah English DramaDocument6 pagesNaskah English DramaAkhmad Risqulloh KrisdiyantoNo ratings yet

- 2015.98225.annals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institutevol32part1!4!1951 TextDocument404 pages2015.98225.annals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institutevol32part1!4!1951 TextPRATIK GANGULY100% (1)

- A Critical Introduction To Modern Arabic PoetryDocument375 pagesA Critical Introduction To Modern Arabic PoetryAnggaTrioSanjayaNo ratings yet

- The Poetics of Robert Frost - Examples Figurative LanguageDocument4 pagesThe Poetics of Robert Frost - Examples Figurative LanguageshugyNo ratings yet

- Alexandre Dumas (Document15 pagesAlexandre Dumas (alexNo ratings yet

- Ernest Hemingway - Cat in The Rain' AnalysisDocument3 pagesErnest Hemingway - Cat in The Rain' AnalysisJust ForfunNo ratings yet

- Discuss Hughes' Use of Dreams and Occult SymbolismDocument16 pagesDiscuss Hughes' Use of Dreams and Occult SymbolismJimmi KhanNo ratings yet

- Tracing A Gypsy Mixed Language Through Medieval and Early ModernDocument44 pagesTracing A Gypsy Mixed Language Through Medieval and Early ModernNicoleta AldeaNo ratings yet

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (83)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentFrom EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- The Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (215)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklFrom EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsFrom EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- The Magical Approach: Seth Speaks About the Art of Creative LivingFrom EverandThe Magical Approach: Seth Speaks About the Art of Creative LivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindFrom EverandThere Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (71)

- The Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaFrom EverandThe Jew in the Lotus: A Poet's Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist IndiaNo ratings yet

- Knocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldFrom EverandKnocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (64)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessFrom EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (60)

- Summary: The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living By Ryan Holiday: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living By Ryan Holiday: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNo ratings yet

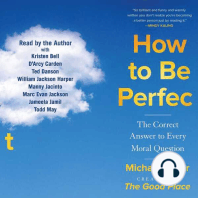

- How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionFrom EverandHow to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (194)

- Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentFrom EverandWhy Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (753)