Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Study Guide 3 LT5docx

Uploaded by

MONICA AYALA0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views7 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views7 pagesStudy Guide 3 LT5docx

Uploaded by

MONICA AYALACopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

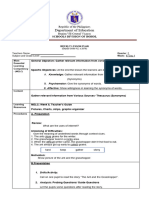

Study Guide 3: Foundations of Curriculum

Week 3

Ayala, Kyla Marie A.

2nd year, BEED

Learning Task 5

Franklin Bobbitt (1876–1956)

A professor of educational

administration at the University of

Chicago, was a pioneer in creating

curriculum as a field of expertise

within the science of education during

the first three decades of the twentieth

century. Bobbitt was born in English,

Indiana, a small town in the state's

southeast corner with a population of fewer than 1,000 people. He

attended Indiana University for his undergraduate degree and then

went on to teach, first in rural Indiana schools and then at the

Philippine Normal School in Manila. He joined the faculty of the

University of Chicago after obtaining his Ph.D. from Clark

University in 1909 and stayed there until his retirement in 1941.

As part of his university responsibilities, Bobbitt conducted

quarterly surveys of local school districts, evaluating their

operations, notably the quality of their curricula. A 1914 review

of the San Antonio Public Schools and a 1922 analysis of the Los

Angeles City Schools' curriculum are two of his most well-known

surveys. The Curriculum (1918) and How to Make a Curriculum

(1919) are two of Bobbitt's best-known works (1924). In these and

other works, he established a philosophy of curriculum

development based on the ideas of scientific management, which

had been defined earlier in the century by engineer Frederick

Winslow Taylor in his attempts to make American industry more

efficient.

Bobbitt's Contribution

Bobbitt's legacy falls into four areas. First, he was one of the

first American educators to advance the case for the

identification of objectives as the starting point for curriculum

making. He, along with the authors of the National Education

Association's Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education, argued

that the content of the curriculum was not self-evident in the

traditional disciplines of knowledge, but had to be derived from

objectives that addressed the functions of adult work and

citizenship. Bobbitt did not value education in and of itself.

It’s worth was in the preparation is provided for children's

adult life. Second, his so-called scientific approach to

curriculum development served as a model for many educators over

the following half-century in laying out the methods for creating

study programs. It was a strategy that became and has remained

the accepted wisdom among American educators when it comes to the

construction of curricula. Third, Bobbitt and other early-

twentieth-century efficiency-oriented school reformers argued

that the curriculum should be differentiated into multiple

tracks, some academic and preparatory and others vocational and

terminal, and that students should be directed to these tracks

based on their abilities. His work lends credibility to

initiatives to vocational the curriculum, as well as to

techniques like tracking and ability grouping, which have become

one of the most contentious aspects of the current school

curriculum. Finally, Bobbitt was one of the first American

educators to describe the curriculum as social control or

regulatory tool for solving modern society's issues. He regarded

the mission of schools as imparting in children the skills,

information, and beliefs they needed to operate in the urban,

industrial, and more heterogeneous society that America was

becoming during the early years of the twentieth century,

according to the principles of social efficiency.

Werrett Wallace Charters (1875–1952)

was a trailblazer in teacher education

and curriculum development research.

His scientific approach to curriculum creation based on life

activity analysis pioneered a new discipline of curriculum

research. Charters was born in Hartford, Ontario, and attended

Hartford Village School before enrolling at McMaster University

in Toronto for a year after graduating from Hagersville High

School. He took a two-year sabbatical from McMaster to teach at

the Rockford Public School before returning to complete his

bachelor's degree in art. Charters has always been a leader, and

during his last year at McMaster, he served as class president.

His alma institution awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1923.

Charters graduated from Ontario Normal College with a teaching

credential in 1899 and went on to become the principal of

Hamilton City Model School. He eventually became the school's

administrator and a teacher-in-training instructor. His teacher

preparation practices were so successful that the Board of

Examiners designated the Hamilton Model School as Ontario's top

model school. Charters went on to obtain a bachelor's degree from

the University of Toronto, a master's degree from the University

of Chicago, and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. His

dissertation advisor was John Dewey, a prominent educational

philosopher and the first Laureate of Kappa Delta Pi. Charters

served as principal of the Winona State Normal School in

Minnesota after obtaining his Ph.D. before going to the

University of Missouri as a Professor of Theory of Teaching and

Dean of the School of Education. Charters went around Missouri to

visit and evaluate high schools, frequently walking miles between

train stations and the schools themselves because they were

particularly concerned about education in rural schools. In 1909,

he published his first book, Methods of Teaching. Charters taught

at four universities between 1917 and 1928: The University of

Illinois, Carnegie Institute of Technology, University of

Pittsburgh, and University of Chicago. He left the University of

Chicago in 1928 to join The Ohio State University as Professor of

Education and Director of the Bureau of Educational Research.

From 1920 to 1949, he was the Director of Research at Stephen's

College in Columbia, Missouri.

Harold Rugg (1886–1960)

One of the most well-known educators

during the Progressive era in the

United States was a long-time

professor of education at Teachers

College, Columbia University. From

1929 through the early 1940s, he

published the first-ever series of

school textbooks. Rugg was the son of

a carpenter and was born in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. His early

poverty seemed to keep him from going to college. Despite this,

he was accepted to Dartmouth College, where he received a

bachelor's degree in civil engineering in 1908 and a master's

degree in civil engineering from Dartmouth's Thayer School of

Civil Engineering in 1909. Rugg worked as a civil engineer for a

short time before teaching civil engineering at Milliken

University in Decatur, Illinois, where he developed an interest

in student learning. In 1915, he earned a doctorate in education

from the University of Illinois, and he began his collegiate

teaching career at the University of Chicago, where he remained

until 1920. He subsequently proceeded to Columbia University's

Teachers College, where he taught until 1951 when he retired.

After retiring, he continued to write educational publications

and worked as an educational consultant in Egypt and Puerto Rico.

Rugg was a co-founder of the National Council for Social Studies

and published yearbooks for several prestigious educational

institutions. Rugg, on the other hand, stayed away from such

groups' duties and responsibilities, preferring to focus on his

study and writing endeavors.

References:

Franklin Bobbitt (1876–1956) - Social Efficiency Movement, Bobbitt's

Contribution - Curriculum, Education, Century, and Schools -

StateUniversity.com https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1794/Bobbitt-

Franklin-1876-1956.html#ixzz74Q7Ac0ip

Charters, W. W. 1923. Curriculum construction. New York: Macmillan.

Charters, W. W. 1933. Motion pictures and youth: A summary. New York:

Macmillan.

Dale, E. 1970. Associations with W. W. Charters. Theory into

Practice 9(2):116–18.

Johnson, B. L. 1953. Werrett Wallace Charters: Particularly his contributions

to higher education. The Journal of Higher Education 24(5): 236–40, 281.

Kliebard, H. M. 1975. The rise of scientific curriculum making and its

aftermath. Curriculum Theory Network 5(1): 27–37.

Rosenstock, S. A. 1984. The educational contributions of W(erret) W(allace)

Charters. Ph.D. diss., The Ohio State University, Columbus.

Seguel, M. L. 1966. The curriculum field: Its formative years. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Wraga, W. G. 2003. Charters, W. W. 1875–1952. In Encyclopedia of Education,

Vol. 1, 2nd ed., ed J. W. Guthrie, 263–65. New York: McMillan.

Harold Rugg (1886–1960) - Education, Social, School, and Curriculum -

StateUniversity.com https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2381/Rugg-

Harold-1886-1960.html#ixzz74R2NWLW9

You might also like

- Perspectives on Higher Education: Eight Disciplinary and Comparative ViewsFrom EverandPerspectives on Higher Education: Eight Disciplinary and Comparative ViewsNo ratings yet

- The School and the University: An International PerspectiveFrom EverandThe School and the University: An International PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- William KilpatrickDocument4 pagesWilliam KilpatrickCyryhl GutlayNo ratings yet

- The Six Famous Curriculum TheoristsDocument7 pagesThe Six Famous Curriculum TheoristsAileen Maristela CapiaNo ratings yet

- Building Bridges HaroldDocument17 pagesBuilding Bridges HaroldMariel M. MontellanaNo ratings yet

- Central Bicol State University of Agriculture-SipocotDocument6 pagesCentral Bicol State University of Agriculture-SipocotRhona Baraquiel PonayoNo ratings yet

- Biography of Hilda TabaDocument1 pageBiography of Hilda Tababonifacio gianga jr0% (1)

- Ballon - M2 - L2.4 Act 1Document8 pagesBallon - M2 - L2.4 Act 1Rose Marie BallonNo ratings yet

- John U. Michaelis, Education: BerkeleyDocument2 pagesJohn U. Michaelis, Education: BerkeleyDonn Ed Martin AbrilNo ratings yet

- Foundation of CurriculumDocument27 pagesFoundation of CurriculumShari Naluis EngalanNo ratings yet

- George Sylvester CountsDocument16 pagesGeorge Sylvester CountsAshly Joy EdquilaNo ratings yet

- Foundation of The CurriculumDocument27 pagesFoundation of The CurriculumShari Naluis EngalanNo ratings yet

- Higher Education As A Field of Study and Its ChallengesDocument4 pagesHigher Education As A Field of Study and Its ChallengesIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development: Submitted By: Ian Israel T. AtienzaDocument6 pagesCurriculum Development: Submitted By: Ian Israel T. AtienzaIan AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Community Colleges in America: A Historical Perspective: by Richard L. DruryDocument6 pagesCommunity Colleges in America: A Historical Perspective: by Richard L. DruryTanushNo ratings yet

- Hilda Taba (Dictionary Entry)Document3 pagesHilda Taba (Dictionary Entry)Maria Angela Cagud PangantihonNo ratings yet

- Biography Theodore BrameldDocument3 pagesBiography Theodore BrameldMartha RussoNo ratings yet

- William H. KilpatrickDocument2 pagesWilliam H. KilpatrickChixee ShanNo ratings yet

- William S. Gray: Coatsburg, Illinois Adams County, IllinoisDocument1 pageWilliam S. Gray: Coatsburg, Illinois Adams County, Illinoisanon_190252717No ratings yet

- bellack1969Document10 pagesbellack1969Innoj MacoNo ratings yet

- Tled 156Document2 pagesTled 156Cherika Lhen Taylan ButacNo ratings yet

- Cluster 1Document7 pagesCluster 1Gay-ong FreylNo ratings yet

- Different Philosophers and Their Contributions to EducationDocument39 pagesDifferent Philosophers and Their Contributions to Educationmarygrace labataNo ratings yet

- CD Assignment 2 (021117)Document6 pagesCD Assignment 2 (021117)Lemuel CondesNo ratings yet

- The Taba Tyler RationalesDocument12 pagesThe Taba Tyler RationalesCatherine AbergosNo ratings yet

- Meloudie T. Aniñon Jane A. Buca Dieann I. Eson Athens Camille Degamo Via Ayla VillaDocument14 pagesMeloudie T. Aniñon Jane A. Buca Dieann I. Eson Athens Camille Degamo Via Ayla VillaDieann KnowesNo ratings yet

- Colin Brock - A TributeDocument2 pagesColin Brock - A TributeRampu PetruNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Education of Robert Maynard HutchinsDocument69 pagesThe Philosophy of Education of Robert Maynard HutchinsAnayat aliNo ratings yet

- Woodring 1975 The Development of Teacher EducationDocument24 pagesWoodring 1975 The Development of Teacher EducationJoe CheeNo ratings yet

- Model Taba 2Document2 pagesModel Taba 2syazayasminismail100% (2)

- Rizal Memorial Colleges, IncDocument9 pagesRizal Memorial Colleges, Incmark ceasarNo ratings yet

- Influential Education Theorist John Franklin BobbittDocument3 pagesInfluential Education Theorist John Franklin BobbittChixee ShanNo ratings yet

- The Taba-Tyler Rationales for Curriculum DevelopmentDocument12 pagesThe Taba-Tyler Rationales for Curriculum DevelopmentIsaacUrsulaNo ratings yet

- From Kilpatrick's Project Method to Project-Based LearningDocument17 pagesFrom Kilpatrick's Project Method to Project-Based LearningCyryhl GutlayNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Thougths On Education-Counts Brameld FreireDocument41 pagesPhilosophical Thougths On Education-Counts Brameld FreireJEZZEL A. RABENo ratings yet

- Historical Development of Social Studies in Different Key NationsDocument8 pagesHistorical Development of Social Studies in Different Key NationsRaquisa Joy LinagaNo ratings yet

- Hollis CaswellDocument2 pagesHollis Caswelljovenborromeo78No ratings yet

- K-12 CLASSROOM ASSESSMENT GUIDELINESDocument6 pagesK-12 CLASSROOM ASSESSMENT GUIDELINESJb VictorioNo ratings yet

- John Dewey: A Pioneer in Educational PhilosophyDocument8 pagesJohn Dewey: A Pioneer in Educational PhilosophyCandra Nuri MegawatiNo ratings yet

- John Franklin BobbittDocument2 pagesJohn Franklin BobbittRio PendonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5: Experimental CollegeDocument8 pagesChapter 5: Experimental CollegeAngela J. SmithNo ratings yet

- Education - Interview With David Pierpont Gardner 021-10-16Document7 pagesEducation - Interview With David Pierpont Gardner 021-10-16pgandzNo ratings yet

- College of Education Department of Elementary and Secondary EducationDocument3 pagesCollege of Education Department of Elementary and Secondary EducationJames Clarenze VarronNo ratings yet

- College of Education Department of Elementary and Secondary EducationDocument3 pagesCollege of Education Department of Elementary and Secondary EducationJames Clarenze VarronNo ratings yet

- Theodore Brameld: Philosopher and EducatorDocument2 pagesTheodore Brameld: Philosopher and EducatorVanenggggNo ratings yet

- Systematic Destruction of American Education Fawcett 1981 1pg EDUDocument1 pageSystematic Destruction of American Education Fawcett 1981 1pg EDUWeirpNo ratings yet

- Francisco FDocument3 pagesFrancisco FErika May A. GuquibNo ratings yet

- The Taba Curriculum FrameworkDocument2 pagesThe Taba Curriculum FrameworkMarifer DineroNo ratings yet

- PRELIMS GROUP Foundation of Curriculum.Document12 pagesPRELIMS GROUP Foundation of Curriculum.Beberly Kim AmaroNo ratings yet

- 40Th Anniversary Retrospective: Overseas Study at Indiana UniversityFrom Everand40Th Anniversary Retrospective: Overseas Study at Indiana UniversityNo ratings yet

- TylerDocument7 pagesTylerHadassah Joy EginoNo ratings yet

- Historyandsocialstudiescurriculum ORE Ross2020Document36 pagesHistoryandsocialstudiescurriculum ORE Ross2020Takudzwa GomeraNo ratings yet

- Module 3 What is the New Social StudiesDocument9 pagesModule 3 What is the New Social StudiesMaisa VillafuerteNo ratings yet

- Parcon - PHILOSOPHERS IN EDUC - 1Document7 pagesParcon - PHILOSOPHERS IN EDUC - 1Saire Chrysbelle ParconNo ratings yet

- Social StudiesDocument3 pagesSocial StudiesManuel Delfin Jr.No ratings yet

- Art12 PDFDocument17 pagesArt12 PDFrequiem1987No ratings yet

- More Than 10,000 Teachers: Hollis L. Caswell and The Virginia Curriculum Revision ProgramDocument23 pagesMore Than 10,000 Teachers: Hollis L. Caswell and The Virginia Curriculum Revision ProgramJohannah AlinorNo ratings yet

- Jacques Maritain's Philosophical Journey to ThomismDocument11 pagesJacques Maritain's Philosophical Journey to ThomismCarlo Descutido100% (1)

- Essentialism: Back to Basics EducationDocument24 pagesEssentialism: Back to Basics EducationGanah MohamedNo ratings yet

- 1562229628974192Document33 pages1562229628974192Phuong NgocNo ratings yet

- Punctuation-Worksheet 18666Document2 pagesPunctuation-Worksheet 18666WAN AMIRA QARIRAH WAN MOHD ROSLANNo ratings yet

- African Journalof Auditing Accountingand FinanceDocument13 pagesAfrican Journalof Auditing Accountingand FinanceTryl TsNo ratings yet

- JPT Jan 2013Document119 pagesJPT Jan 2013Maryam IslamNo ratings yet

- 07 - Toshkov (2016) Theory in The Research ProcessDocument29 pages07 - Toshkov (2016) Theory in The Research ProcessFerlanda LunaNo ratings yet

- Insertion Mangement Peripheral IVCannulaDocument20 pagesInsertion Mangement Peripheral IVCannulaAadil AadilNo ratings yet

- 5S and Visual Control PresentationDocument56 pages5S and Visual Control Presentationarmando.bastosNo ratings yet

- Meng Chen, Lan Xu, Linda Van Horn, Joann E. Manson, Katherine L. Tucker, Xihao Du, Nannan Feng, Shuang Rong, Victor W. ZhongDocument1 pageMeng Chen, Lan Xu, Linda Van Horn, Joann E. Manson, Katherine L. Tucker, Xihao Du, Nannan Feng, Shuang Rong, Victor W. ZhongTHLiewNo ratings yet

- An Umbrella For Druvi: Author: Shabnam Minwalla Illustrator: Malvika TewariDocument12 pagesAn Umbrella For Druvi: Author: Shabnam Minwalla Illustrator: Malvika TewariKiran Kumar AkulaNo ratings yet

- Simulation of Spring: Date: Martes, 25 de Agosto de 2020 Designer: Solidworks Study Name: Resorte 1 Analysis TypeDocument10 pagesSimulation of Spring: Date: Martes, 25 de Agosto de 2020 Designer: Solidworks Study Name: Resorte 1 Analysis TypeIván D. ArdilaNo ratings yet

- Explosive Ordnance Disposal & Canine Group Regional Explosive Ordnance Disposal and Canine Unit 3Document1 pageExplosive Ordnance Disposal & Canine Group Regional Explosive Ordnance Disposal and Canine Unit 3regional eodk9 unit3No ratings yet

- Competences Needed in Testing - Handout Manual PDFDocument97 pagesCompetences Needed in Testing - Handout Manual PDFCristina LucaNo ratings yet

- Is 5312 1 2004Document13 pagesIs 5312 1 2004kprasad_56900No ratings yet

- Ken Scott - Metal BoatsDocument208 pagesKen Scott - Metal BoatsMaxi Sie100% (3)

- Chapter 2 - DynamicsDocument8 pagesChapter 2 - DynamicsTHIÊN LÊ TRẦN THUẬNNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Prefabricated MyofunctionalDocument10 pagesEffectiveness of Prefabricated MyofunctionalAdina SerbanNo ratings yet

- CS 401 Artificial Intelligence: Zain - Iqbal@nu - Edu.pkDocument40 pagesCS 401 Artificial Intelligence: Zain - Iqbal@nu - Edu.pkHassan RazaNo ratings yet

- Lipid ChemistryDocument93 pagesLipid ChemistrySanreet RandhawaNo ratings yet

- How To Install Elastix On Cloud or VPS EnviornmentDocument4 pagesHow To Install Elastix On Cloud or VPS EnviornmentSammy DomínguezNo ratings yet

- Document 3Document5 pagesDocument 3SOLOMON RIANNANo ratings yet

- EVE 32 07eDocument45 pagesEVE 32 07eismoyoNo ratings yet

- USSBS Report 54, The War Against Japanese Transportation, 1941-45Document206 pagesUSSBS Report 54, The War Against Japanese Transportation, 1941-45JapanAirRaids100% (2)

- 2023 SPMS Indicators As of MarchDocument22 pages2023 SPMS Indicators As of Marchcds documentNo ratings yet

- Processed oDocument2 pagesProcessed oHemanth KumarNo ratings yet

- A Gringa in Oaxaca PDFDocument54 pagesA Gringa in Oaxaca PDFPeggy BryanNo ratings yet

- Essay 2Document13 pagesEssay 2Monarch ParmarNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument4 pagesCase AnalysisAirel Eve CanoyNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Types of Hydrogen Fuel CellDocument57 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Different Types of Hydrogen Fuel CellSayem BhuiyanNo ratings yet

- Bohol - Eng5 Q2 WK8Document17 pagesBohol - Eng5 Q2 WK8Leceil Oril PelpinosasNo ratings yet

- Advertising ContractDocument3 pagesAdvertising Contractamber_harthartNo ratings yet