Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Surgery During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Operating Room Suggestions From An International Delphi Process

Uploaded by

Jey Gee DeeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Surgery During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Operating Room Suggestions From An International Delphi Process

Uploaded by

Jey Gee DeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Original article

Surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: operating room

suggestions from an international Delphi process

Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative*

Swansea University Medical School, Swansea University, Swansea, UK

Correspondence to: Mr A. J. Beamish, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea University, Swansea SA2 8QA, UK (e-mail: beamishaj@gmail.com)

Background: Operating room (OR) practice during the COVID-19 pandemic is driven by basic princi-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

ples, shared experience and nascent literature. This study aimed to identify the knowledge needs of the

global OR workforce, and characterize supportive evidence to establish consensus.

Methods: A rapid, modified Delphi exercise was performed, open to all stakeholders, informed via an

online international collaborative evaluation.

Results: The consensus exercise was completed by 339 individuals from 41 countries (64⋅3 per cent

UK). Consensus was reached on 71 of 100 statements, predominantly standardization of OR pathways,

OR staffing and preoperative screening or diagnosis. The highest levels of consensus were observed in

statements relating to appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and risk distribution (96–99

per cent), clear consent processes (96 per cent), multidisciplinary decision-making and working (97

per cent). Statements yielding equivocal responses predominantly related to technical and procedure

choices, including: decontamination (40–68 per cent), laminar flow systems (13–61 per cent), PPE reuse

(58 per cent), risk stratification of patients (21–48 per cent), open versus laparoscopic surgery (63 per

cent), preferential cholecystostomy in biliary disease (48 per cent), and definition of aerosol-generating

procedures (19 per cent).

Conclusion: High levels of consensus existed for many statements within each domain, supporting much

of the initial guidance issued by professional bodies. However, there were several contentious areas, which

represent urgent targets for investigation to delineate safe COVID-19-related OR practice.

∗ Members of the Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative are co-authors of this study and are listed

in Appendix S1 (supporting information)

Paper accepted 11 May 2020

Published online 27 June 2020 in Wiley Online Library (www.bjs.co.uk). DOI: 10.1002/bjs.11747

Introduction when confronted with serious, changing and evidence-poor

states3 . The aim of this study was to identify the knowl-

The COVID-19 pandemic has all but stopped planned

edge needs of the global OR workforce, to characterize the

surgical treatment1 as a result of hospital capacity con-

available supporting evidence, and to establish consensus

straints, and the swift recognition that COVID-19 poses an

by means of a rapid modified Delphi process to inform safe

important danger to patients and healthcare professionals

surgical practice.

alike2 .

Operating room (OR) practice, like many aspects of

the response to COVID-19, has been driven predomi-

nantly by basic principles and shared experience, in the Methods

absence of a reliable evidence base3 . Wide variation in

practice is therefore predictable, and early clinical guid- Full details of the study design, methods employed and sta-

ance is disproportionately reliant on the expert opinion tistical analysis can be found in Appendix S2 (supporting

of small committees4–8 . Although beneficial in aligning information). In brief, a collaborative evaluation process

early OR practice, such leadership cannot hope to integrate was undertaken using social media, informing the devel-

the perspectives of the wider medical community. More- opment of a series of statements in a single-phase Delphi

over, contemporary research methods appear of limited use exercise.

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Delphi consensus on operating room best practice in COVID-19 1451

Table 1 Specialty, grade and highest academic achievement of participants

No. of No. of Highest academic No. of

Specialty participants Grade participants achievement participants

Surgeon 279 (82⋅3) Consultant/attending/equivalent 204 (60⋅2) Doctorate 137 (40⋅4)

Anaesthetist/intensivist 29 (8⋅6) Registrar/resident/equivalent 96 (28⋅3) Masters 119 (35⋅1)

Other medical professional 15 (4⋅4) Foundation/intern/core/senior 21 (6⋅2) Bachelor 74 (21⋅8)

house officer/equivalent

Nurse 9 (2⋅7) Not known 18 (5⋅3) Other professional qualification 6 (1⋅7)

Operating department practitioner 5 (1⋅5) High school 3 (0⋅9)

Microbiologist/virologist 1 (0⋅3)

Other non-medical professional 1 (0⋅3)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

Values in parentheses are percentages.

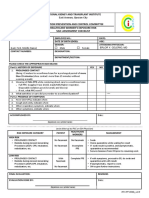

Fig. 1 World map choropleth of Delphi consensus exercise participation

1 2–5 6–1516–50 > 50

Numbers in the key represent Delphi participants.

Results Phase III

Phases I and II The consensus exercise was completed by 339 individuals

(279 surgeons, 82⋅3 per cent). Respondents were predom-

Phase I generated 127 questions, which were rationalized

to 104 questions for use in phase II (Appendix S3, support- inantly consultants/attendings (204, 60⋅2 per cent), and a

ing information). A total of 345 responses were received majority reported their highest academic achievement as

during phase II, and 108 sources of evidence/policies a doctorate (137, 40⋅4 per cent) or masters degree (119,

shared by participants. All contributed interactions 35⋅1 per cent) (Table 1). Responses were received from 41

and information sources were collated to produce the countries, across all six WHO regions1 , with a majority

100 consensus statements. A high level of engagement based in the UK (64⋅3 per cent) (Fig. 1; Table S2, supporting

via Twitter® (http://twitter.com) was achieved, with information).

more than 475 000 impressions across 28 days (Table S1, Consensus was determined across four domains: physical

supporting information). resources, personnel, patients and procedures.

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1452 Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative

Table 2 Consensus appropriate in domain 1: physical resources

No. responding

Agree Unsure Disagree ‘outside of my expertise’

(%) (%) (%) (n = 339)

Consensus agree

Single-use equipment should be used preferentially in patients with 88 5 7 5

COVID

Reusable equipment should be covered with impermeable coverings, 78 16 6 33

while ensuring machinery safety is maintained (e.g. vents

unobstructed)

ORs should be filtered and ventilated, ideally with negative pressure, for 87 10 3 19

patients with COVID

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

Intubation and extubation should take place within a negative pressure 89 9 2 27

room where possible

Where possible, elective surgery should be conducted in hospitals 81 8 11 4

designated as non-COVID or clean sites

Separate ORs and access routes should be used for patients with COVID 94 3 3 2

Donning/doffing should take place in clearly identified clean, partially 96 3 1 5

contaminated, and contaminated areas according to a clear protocol

Equivocal

Surgical equipment used in patients with COVID should have separate 60 19 20 48

decontamination pathways

Where laminar flow is available this should be active for at least 20 min 61 29 10 13

before intubation and after any procedure

OR temperature makes a difference to transmission risk in patients with 13 73 15 61

COVID

The effects of laminar flow, negative and positive OR pressure on droplet 13 33 54 42

spread in COVID are well understood

The OR can safely be used again 20 min after cleaning following the 40 45 15 45

previous procedure, keeping the ventilation running

Suitable surface cleaning agents are: 68–72% ethanol, or 0⋅5% peroxide; 61 37 2 62

combined or separate detergent and disinfectant (1000 ppm available

chlorine). Chlorhexidine is ineffective against coronavirus

OR cleaning should be performed after waiting at least 20 min from the 68 27 5 38

end of procedure/patient extubation

Consensus agree: more than 70 per cent agree, less than 25 per cent disagree; consensus disagree: more than 70 per cent disagree, less than 25 per cent

agree; non-consensus: at least 33 per cent agree, at least 33 per cent disagree; equivocal: all other combinations. OR, operating room.

Domain 1 (physical resources) comprised 14 statements temperature. In particular, there was doubt regarding the

(Table 2), seven of which were deemed appropriate by con- effects of OR pressure and flow systems on droplet spread,

sensus (agreement range 78–96 per cent); the remain- as well as the timing of subsequent OR use. However,

ing seven statements were equivocal (13–68 per cent there was consensus that intubation and extubation should

agreement). be performed in a negative pressure environment, which

Statements with consensus agreement supported a is supported by anaesthetic and intensive care professional

distinction between protocols involving patients with organizations4,8 .

suspected COVID-19 and those perceived to be free Domain 2 (personnel) included 25 statements (Table 3),

from infection. Suggestions from this domain included 19 of which reached consensus agreement (74–99 per cent

clear demarcation of clean versus contaminated areas, agreement). Five statements were equivocal (45–68 per

OR access routes, and hospitals, as well as utilizing cent agreement), and there was clear consensus disagree-

single-use equipment with disposable protective equip- ment with the statement: ‘the coronavirus transmission risk

ment covering. Although firm evidence is lacking for of anaesthetic and surgical procedures is well understood’.

these approaches, emerging guidance documents support There was a clear desire for uniformity of practice, and

their implementation4,6–8 . Statements that failed to gar- strong support for national and international guidance, in

ner consensus related to decontamination processes for preference to local policies. Participants supported uni-

the OR and surgical equipment, laminar flow and OR versal adoption of WHO personal protective equipment

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Delphi consensus on operating room best practice in COVID-19 1453

Table 3 Consensus appropriate in domain 2: personnel

No. responding

Agree Unsure Disagree ‘outside of my expertise’

(%) (%) (%) (n = 339)

Consensus agree

Every staff member must receive formal training in PPE use before any 99 0 1 0

contact with potential patients with COVID

PPE definition should universally be based on WHO guidance to avoid 83 9 9 6

confusion

PPE level should be determined by (inter)national guidance rather than local 85 7 8 1

policy

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

The minimum standard for ‘full’ PPE should include: double layers of 92 4 4 5

disposable gloves, water-resistant gown with full-length sleeves, eye

protection and N95–99/FFP2–3 mask

In non-theatre environment PPE should follow WHO guidance: close 89 6 6 5

contact – mask, gown, gloves, face mask/goggles; AGP – respirator

(FFP2/N95), gown, gloves, face mask/goggles, sleeved apron

Clear local plans should be outlined in case supplies of PPE run low or run out 96 3 2 2

All staff in theatre should use the same level of PPE for patients with COVID, 74 11 15 5

regardless of proximity to the patient

Teams should practice doffing procedures in advance, following an agreed 97 1 2 2

protocol

Dentists should follow the same PPE guidance as other disciplines working 95 4 1 42

close to upper airways

Mask fit testing hoods should be cleaned between each tested person 86 13 1 24

Where adequate PPE is unavailable, procedures should not be performed 74 19 7 3

Only essential staff should be in the OR for patients with COVID, with no 98 1 1 1

exchange of room staff, except for emergency situations

The minimum number of necessary providers should attend patients during 99 1 0 1

rounds and other encounters

The most senior person available should perform procedures (e.g. 75 9 15 2

operating/intubating)

Duties involving close contact should be shared out or spaced out to 78 16 6 9

minimize viral exposure of OR personnel

Staff at high risk (e.g. immunosuppressed) should be shielded from 96 4 0 2

patient-facing duties

Communication devices can help minimize staff entry and exit frequency in 94 5 0 4

the OR

Asymptomatic patients with COVID present a risk of transmission during 91 8 1 4

AGPs

Specialties involved in procedures involving and close to the upper airway 95 4 1 7

are at greater risk (e.g. anaesthetics, ear, nose and throat, maxillofacial,

dentistry, neurosurgery)

Equivocal

In non-AGP operations, standard PPE is acceptable if the aerosol has been 45 31 24 26

cleared by OR ventilation after intubation

Prolonged use of PPE can lead to staff injury or harm (e.g. pressure necrosis) 68 23 9 9

Where demand outstrips supply, reuse of disposable N95/N99/FFP2/FFP3 58 27 15 34

masks is feasible if following specific evidence-based guidance

Dual-consultant operating can be clinically beneficial in patients with COVID 60 26 14 14

The transmission risk differs between individual patients with COVID 59 36 5 43

Consensus disagree

The coronavirus transmission risk of anaesthetic and surgical procedures is 15 13 72 6

well understood

Consensus agree: more than 70 per cent agree, less than 25 per cent disagree; consensus disagree: more than 70 per cent disagree, less than 25 per cent

agree; non-consensus: at least 33 per cent agree, at least 33 per cent disagree; equivocal: all other combinations. PPE, personal protective equipment; AGP,

aerosol-generating procedure; OR, operating room.

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1454 Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative

Table 4 Consensus appropriate in domain 3: patients

No. responding

Agree Unsure Disagree ‘outside of my expertise’

(%) (%) (%) (n = 339)

Consensus agree

All patients should be considered to be COVID contagious unless proven otherwise 90 4 6 4

during the pandemic

All patients attending hospital during the pandemic should wear a surgical mask 75 16 9 10

from arrival

The thorax should be included in emergency abdominal CT in patients with 90 6 4 12

unknown COVID status

Although false-negative rates remain substantial, COVID status should be assessed 71 19 10 34

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

using CT of the thorax in patients with unknown COVID status requiring

(non-emergency) urgent surgery (e.g. cancer)

Where safe and possible, surgical patients should be tested before operation for 95 4 2 1

COVID-19

Screening questions are a poor way to identify potential patients with COVID 73 17 9 18

Despite the effect of COVID on practice, the consent process should keep the 91 5 4 3

patient as the main focus

Consent discussions with patients must cover the added risk of COVID exposure 96 4 0 1

and the potential consequences

Patients with COVID should be on a separate operating list, or last on the list where 87 7 6 2

this is not possible

Patients COVID with should be isolated after surgery 94 6 1 1

Equivocal

Negative CT of the thorax, or at least two negative swabs without subsequent 48 31 21 41

exposure, are sufficient to define negative COVID status

The patient’s viral load can help predict postoperative outcomes and aid decisions 27 65 8 75

on management

Coronavirus in gastrointestinal secretions and faeces does not represent a 9 31 60 36

transmission risk

Risk scores such as P-POSSUM are equally applicable to patients with COVID 21 54 25 61

Surgery should be contraindicated in patients with COVID and related poor 31 40 29 31

prognostic indicators (e.g. raised D-dimer/LDH)

Perioperative antibiotic regimens should take consideration of the level of suspicion 44 25 31 35

of COVID

Consensus agree: more than 70 per cent agree, less than 25 per cent disagree; consensus disagree: more than 70 per cent disagree, less than 25 per cent

agree; non-consensus: at least 33 per cent agree, at least 33 per cent disagree; equivocal: all other combinations. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

(PPE) definitions, and suggest training and protocolized remaining six statements were equivocal (9–48 per cent

deployment of PPE, which was largely recommended by agreement).

government agencies9–12 and professional bodies4–8,13,14 . Responses highlighted uncertainty regarding the risk of

Moreover, there was consensus that appropriate PPE was transmission of COVID-19, as well as diagnostic mea-

not only essential, but that procedures should not be per- sures. Caution in OR practice was suggested, treating all

formed where adequate PPE was unavailable, a sentiment patients as suspected cases, using patient masks where sta-

supported by the Royal College of Surgeons of England6 . tus is unknown, testing early, avoiding reliance on screen-

Disposable PPE reuse was not generally supported, despite ing questions, and isolating patients around the time of

evidence outlining several potentially effective and safe surgery. This approach reflects an appreciation of the

methods14 . Dual-consultant team operating practice was silent phase of COVID-19, when patients may be conta-

perceived to be equivocal, which arguably reflects concern gious, but asymptomatic15 . Consensus was poor regard-

relating to the exposure of two senior specialists to a risk of ing the adequate definition of true-negative COVID-19

COVID-19 infection, limited efficiency, or the variety of status, arguably reflecting suboptimal diagnosis by means

procedural complexity undertaken by Delphi participants. of oropharyngeal (32–72 per cent) and nasopharyngeal

Domain 3 (patients) yielded consensus agreement in ten (63–73 per cent) tests16 . Thoracic CT use was strongly

of 16 statements (71–96 per cent agreement) (Table 4). The supported in patients undergoing emergency abdominal

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Delphi consensus on operating room best practice in COVID-19 1455

Table 5 Consensus appropriate in domain 4: procedures

No. responding

Agree Unsure Disagree ‘outside of my expertise’

(%) (%) (%) (n = 339)

Consensus agree

Laparoscopy should be considered a coronavirus AGP 75 19 7 33

Filter devices should be used for releasing smoke and CO2 during and after laparoscopy 88 10 2 36

Laparoscopic port-site incisions should be kept as small as possible 85 11 5 37

Laparoscopic CO2 insufflation pressure should be kept to a minimum 83 16 2 38

Predicted length of stay and impact on need for ICU should be taken into account in the 91 7 2 10

choice of procedure

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

Viral contamination of staff is possible during surgery, either open, laparoscopic or 92 6 2 16

robotic

COVID status and its implications should be included in the WHO checklist 91 4 6 2

All elective work should be postponed at present unless delay substantially affects the 91 4 4 1

prognosis

All in-person clinic/office work should be cancelled or delivered electronically, unless 94 4 2 1

this substantially affects the prognosis

AGPs should generally be avoided as far as possible during the pandemic 85 8 7 8

Electrocautery should be used sparingly and on the lowest possible settings for the 76 17 6 29

desired effect

Use of devices that can lead to aerosolization (monopolar electrosurgery, ultrasonic 80 16 3 13

dissectors, advanced bipolar devices) should be minimized

Monopolar diathermy pencils with attached smoke evacuators should be preferred if 88 12 1 25

electrosurgery is required

MDTs should be conducted virtually where possible 97 2 1 2

Maximal PPE should be worn for any laparotomy in patients with COVID 93 4 3 21

Decisions regarding management strategies should be taken by the MDT wherever 97 2 1 4

possible

A short operating time should be prioritized in the procedure choice 75 13 12 8

Non-operative management should be preferentially implemented where possible 85 8 7 15

Routine audit data collection should continue 84 7 9 4

Specific CT features can help determine the safety of conservative management of the 81 11 8 58

acute abdomen

Endovascular approaches should be used as a bridge to open surgery to expedite 78 18 3 107

discharge where feasible

Trauma injuries should preferentially be managed non-surgically where this appears safe 78 15 7 37

in the short term

Sawing or shaving bone constitutes an AGP 72 23 5 99

Endoscopic trans-sphenoidal surgery should be avoided where possible 84 16 0 189

All procedures involving close contact with the face, head and neck should be 96 4 1 27

considered high risk for staff in patients with COVID

Use of any drill in the mouth should be considered an AGP; a rubber dam and 94 6 0 118

high-volume suction should be used where possible

Where endoscopy is essential, staff should wear the recommended PPE appropriate for 96 4 0 23

an AGP

Only emergency endoscopy and urgent cancer evaluations should be performed during 91 6 4 21

the pandemic

Air or CO2 insufflation should be kept to a minimum in endoscopy 89 8 2 56

Endoscopic procedures involving additional insufflation (e.g. endoscopic mucosal 75 21 5 87

resection), should be avoided during the pandemic

Removal of caps on endoscopes could release fluid and/or air and should be avoided 76 20 4 106

PPE practice in endoscopy should mirror that of any other AGP 95 4 1 44

The patient’s temperature should be taken before undertaking endoscopy 76 18 6 44

Patients on immunosuppressive drugs for inflammatory bowel disease or autoimmune 76 23 1 104

hepatitis should continue taking them as the risk of disease flare outweighs risk of

contracting COVID

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1456 Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative

Table 5 Continued

No. responding

Agree Unsure Disagree ‘outside of my expertise’

(%) (%) (%) (n = 339)

Equivocal

Where a CO2 extraction filter is unavailable, an underwater extraction device can safely 31 61 9 75

be used instead

An open approach should be favoured over laparoscopy unless the clinical benefit 63 16 21 30

substantially exceeds the risk of potential viral transmission

It is clear which procedures are aerosol-generating 19 21 61 2

Resected specimens should generally not be examined in the OR 64 23 13 37

Alcoholic povidone–iodine is preferred in COVID as chlorhexidine may not be effective 43 52 5 66

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

against coronavirus

Stoma formation should be considered rather than anastomosis to reduce the need for 64 16 20 42

unplanned postoperative critical care for complications

Cholecystostomy should be considered in preference to cholecystectomy in acute 48 25 27 76

severe cholecystitis

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy should still be performed for acute gallstone pancreatitis 46 29 25 67

Specific biochemical marker cut-offs can help determine the safety of conservative 47 23 29 49

management of the acute abdomen (e.g. C-reactive protein, white cell count)

A preprocedural mouth rinse containing 1% hydrogen peroxide or 0⋅2% povidone 54 43 3 187

should be used in oral procedures. Chlorhexidine is not effective

Gastrointestinal endoscopes should be cleaned as normal 42 35 24 127

Consensus agree: more than 70 per cent agree, less than 25 per cent disagree; consensus disagree: more than 70 per cent disagree, less than 25 per cent

agree; non-consensus: at least 33 per cent agree, at least 33 per cent disagree; equivocal: all other combinations. AGP, aerosol-generating procedure; MDT,

multidisciplinary team; PPE, personal protective equipment; OR, operating room.

CT or requiring urgent surgery, as supported by the UK it has been proposed that electrocautery and ultrasonic

Royal Colleges of Radiologists and Surgeons17 , but not dissector use, which may promote aerosolization, should

by the American College of Radiologists18 . Within the be minimized. Two research groups have reported findings

consent process, inclusion of the potentially substantial regarding surface stability21 and elimination22 of novel

impact of COVID-19 on risk was strongly supported, coronavirus, the latter demonstrating that chlorhexi-

but participants were unsure how best to use risk predic- dine performed poorly in eliminating novel coronavirus.

tion tools, such as P-POSSUM19 , and other novel predic- Despite highlighting this evidence within the Delphi

tive measures in COVID-19, such as D-dimer and lactate exercise, no consensus was achieved regarding the choice

dehydrogenase20 . of decontamination agent.

Domain 4 (procedures) comprised 45 statements With regard to specific surgical specialties and proce-

(Table 5), 34 of which reached consensus (72–97 per dures, a number of themes arose related to the relative

cent agreement). Eleven statements yielded equivocal risks and benefits to both patients and staff conferred by

responses (19–64 per cent agreement). the type of surgical approach. In general surgery, there

Statements related to the postponement of sched- was consensus that laparoscopy represents an AGP, but

uled elective work (unless delay substantially affects the also that laparotomy requires full PPE and, regardless of

prognosis), and provision of virtual multidisciplinary approach (open, laparoscopic or robotic), the potential

team (MDT) meetings achieved consensus, consistent for viral transmission remains potent. No consensus was

with international guidance4,6 . There was support for achieved regarding an open versus laparoscopic approach

cross-specialty MDT decision-making to determine man- and, indeed, although initial official guidance advised

agement strategies, prioritizing procedures associated strongly against laparoscopy, more recent European and

with shorter operating times and duration of hospital of US iterations advise a cautious patient-tailored strategy4,6 .

stay, avoiding intensive care requirement, and preferential Consensus was also poor regarding preferences for spe-

non-operative management where possible. Avoidance of cific management options, such as stoma formation

aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs) was also favoured, versus gastrointestinal anastomosis, cholecystostomy versus

but many respondents disagreed regarding which pro- cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis, and conservative

cedures were actually aerosol-generating. Nevertheless, management of gallstone pancreatitis. A pragmatic,

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Delphi consensus on operating room best practice in COVID-19 1457

patient-specific decision-making process is likely to be Acknowledgements

necessary, taking into consideration local factors such

WSRI Collaborative is grateful for the support of the

as hospital and regional COVID-19 rates, and criti-

Royal College of Surgeons of England and this work is

cal care capacity, for example. Participants agreed that

conducted as part of the Royal College of Surgeons of

all procedures involving the head and neck should be

England COVID Research Group portfolio. This project

classed as high risk, endoscopic trans-sphenoidal surgery

is registered in the Open Science Framework (https://osf

avoided, and intraoral drilling classified as an AGP. Con-

.io/j8zym/).

sensus was lacking regarding preprocedural mouthwash,

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

despite 1 per cent hydrogen peroxide and 0⋅2 per cent

povidone–iodine having been recommended as more

effective than chlorhexidine23 . References

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

In vascular surgery, an endovascular approach was

1 WHO. WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. https://covid19.who

favoured over open surgery, a position supported in .int [accessed 21 April 2020].

abdominal aneurysm repair alone in Vascular Society (UK) 2 Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive

guidance13 . Consensus supported conservative trauma surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned

management where possible, and procedures involving in China and Italy. Ann Surg 2020; https://doi.org/10.1097/

sawing or cutting bone were deemed AGPs, as demon- sla.0000000000003924 [Epub ahead of print].

strated previously24 . For gastrointestinal endoscopy there 3 Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative.

was clear consensus that this represented an AGP and Systematic review of recommended operating room practice

should be limited to emergencies only with appropriate during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJS Open 2020; https://

doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50304.

PPE, concurring with UK and US guidance5,7 .

4 Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic

Surgeons, European Association for Endoscopic Surgery.

SAGES and EAES Recommendations Regarding Surgical

Discussion Response to COVID-19 Crisis. https://www.sages.org/

recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19/ [accessed 21

This study has a number of limitations. Consensus was

April 2020].

achieved using a single-phase Delphi exercise, although 5 American College of Gastroenterology, American Society

this was considered a valid compromise, considering the for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, American Association for

time-sensitive nature of the project and the pandemic. The the Study of Liver Disease, American Gastroenterological

use of an online platform enabled engagement from all Association. Joint Gastroenterology Society Message: COVID-19

six WHO global regions, although participation from the Use of Personal Protective Equipment in GI Endoscopy. https://gi

original epicentre in China was limited by restrictions on .org/2020/04/01/joint-gi-society-message-on-ppe-during-

regional social media use. Some reluctance was also docu- covid-19/ [accessed 21 April 2020].

6 Association of Surgeons of Great Britain & Ireland,

mented from certain Western geographical areas, because

Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland,

of perceived whistle-blower concerns regarding reporting

Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons, Royal

unsatisfactory government strategies. Demographic details College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Royal College of

of participants, such as professional credentials, were not Surgeons of England, Royal College of Physicians and

validated, although it is anticipated that the large number Surgeons of Glasgow et al. Updated Intercollegiate General

of participants mitigated against any self-reporting inaccu- Surgery Guidance on COVID-19. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/

racy. coronavirus/joint-guidance-for-surgeons-v2/ [accessed 21

This study has revealed global expert consensus related April 2020].

to OR practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among 7 British Society of Gastroenterology, Joint Advisory Group,

339 worldwide multidisciplinary experts, consensus was Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland,

Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons, Pancreatic

evident regarding 71 of 100 statements, supporting much

Society of Great Britain and Ireland, UK and Ireland EUS

of the initial guidance issued by a number of professional

Society et al. Endoscopy Activity and COVID-19: BSG and JAG

organizations. The remaining areas of contention, which Guidance – Update 03.04.20. https://www.bsg.org.uk/covid-

were deemed important by stakeholders during the initial 19-advice/endoscopy-activity-and-covid-19-bsg-and-jag-

phases of this study, should be considered key targets for guidance/ [accessed 21 April 2020].

urgent research. The next steps should map these findings 8 Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, Intensive Care Society,

to published guidance to appraise and validate specific Association of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Anaesthetists.

recommendations against global consensus. ICM-Anaesthesia COVID-19- Clinical Guidance.

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1458 Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative

https://icmanaesthesiacovid-19.org/clinical-guidance 16 Yang Y, Yang M, Shen C, Wang F, Yuan J, Li J et al.

[accessed 21 April 2020]. Evaluating the accuracy of different respiratory specimens in

9 Public Health England. COVID-19 Personal Protective the laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding

Equipment (PPE). https://www.gov.uk/government/ of 2019-nCoV infections. MedRXiv 2020.

publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection- 17 Royal College of Radiologists. RCR position on the Role of CT

prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective- in Patients Suspected with COVID-19 Infection. https://www

equipment-ppe [accessed 21 April 2020]. .rcr.ac.uk/college/coronavirus-covid-19-what-rcr-doing/

10 WHO. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Technical Guidance: clinical-information/rcr-position-role-ct-patients [accessed

Infection Prevention and Control. https://www.who.int/ 21 April 2020].

emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical- 18 American College of Radiology. ACR Recommendations for

the use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography

guidance/infection-prevention-and-control [accessed 21

(CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. https://www.acr.org/

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/107/11/1450/6139519 by guest on 20 April 2021

April 2020].

Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/

11 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim

Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-

Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients

Suspected-COVID19-Infection [accessed 21

with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019

April 2020].

(COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/

19 Whiteley MS, Prytherch DR, Higgins B, Weaver PC, Prout

coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control- WG. An evaluation of the POSSUM surgical scoring

recommendations.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F system. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 812–815.

%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov 20 Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z et al. Clinical

%2Finfection-control%2Fcontrol-recommendations.html course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with

[accessed 21 April 2020]. COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study.

12 Health and Safety Executive. Research: Review of Personal Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062.

Protective Equipment Provided in Health Care Settings to 21 van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook

Manage Risk During the Coronavirus Outbreak. https://www MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN et al. Aerosol and surface

.hse.gov.uk/news/assets/docs/face-mask-equivalence- stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1.

aprons-gown-eye-protection.pdf [accessed 21 April 2020]. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1564–1567.

13 Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. COVID-19 22 Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence

Virus and Vascular Surgery. https://www.vascularsociety.org of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their

.uk/professionals/news/113/covid19_virus_and_vascular_ inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect 2020; 104:

surgery [accessed 21 April 2020]. 246–251.

14 Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic 23 Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission

Surgeons. N95 Re-Use Strategies. https://www.sages.org/n- routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int

95-re-use-instructions/ [accessed 21 April 2020]. J Oral Sci 2020; 12: 9.

15 Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, 24 Wenner L, Pauli U, Summermatter K, Gantenbein H,

Wallrauch C et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection Vidondo B, Posthaus H. Aerosol generation during

from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med bone-sawing procedures in veterinary autopsies. Vet Pathol

2020; 382: 970–971. 2017; 54: 425–436.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the

article.

© 2020 BJS Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk BJS 2020; 107: 1450–1458

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

You might also like

- 1 s2.0 S1879729618300073 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S1879729618300073 MainAditiya RonaldiNo ratings yet

- Pone 0101915Document9 pagesPone 0101915Edy Tahir MattoreangNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Collaborative Working On Surgical Ward Rounds Reality or Rhetoric A Systematic ReviewDocument16 pagesInterdisciplinary Collaborative Working On Surgical Ward Rounds Reality or Rhetoric A Systematic ReviewIvan Troy UbandoNo ratings yet

- Annals of Medicine and Surgery: Abraham Tarekegn Mersh, Debas Yaregal Melesse, Wubie Birlie ChekolDocument4 pagesAnnals of Medicine and Surgery: Abraham Tarekegn Mersh, Debas Yaregal Melesse, Wubie Birlie Chekoldwi sariNo ratings yet

- Annals of Medicine and Surgery: Cross-Sectional StudyDocument6 pagesAnnals of Medicine and Surgery: Cross-Sectional StudyAbdullah Ali BakshNo ratings yet

- Impacto Elearning Medical StudensDocument8 pagesImpacto Elearning Medical StudensDeveloper SystemNo ratings yet

- 41 FullDocument16 pages41 Fullraj.insigneNo ratings yet

- BJD 0743Document10 pagesBJD 0743mh8m58brjnNo ratings yet

- 2020 12 01 20240853v1 FullDocument24 pages2020 12 01 20240853v1 Fullpopov357No ratings yet

- Nationwide Standardization of Minimally Invasive Right Hemicolectomy For Colon Cancer and Development and Validation of A Video-Based Competency Assessment ToolDocument9 pagesNationwide Standardization of Minimally Invasive Right Hemicolectomy For Colon Cancer and Development and Validation of A Video-Based Competency Assessment ToolStephany BqNo ratings yet

- BMJ d8041 FullDocument11 pagesBMJ d8041 FullAshu AberaNo ratings yet

- Rituals 02Document27 pagesRituals 02Abhijit KarmarkarNo ratings yet

- Evolution of A Virtual Multidisciplinary Cleft and Craniofacial Team Clinic During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Children's Hospital Colorado ExperienceDocument5 pagesEvolution of A Virtual Multidisciplinary Cleft and Craniofacial Team Clinic During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Children's Hospital Colorado Experiencejaime mezaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery Open: Mengesha Dessie AlleneDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery Open: Mengesha Dessie AllenebejarhasanNo ratings yet

- POCUS 25 Practice DomainsDocument8 pagesPOCUS 25 Practice DomainsrajkumarrajendramNo ratings yet

- Educational Utility of An Online Video-Based Teaching Tool For Sinus and Skull Base SurgeryDocument6 pagesEducational Utility of An Online Video-Based Teaching Tool For Sinus and Skull Base SurgeryTi FaNo ratings yet

- WHO HIV 2013.82 EngDocument19 pagesWHO HIV 2013.82 EngRido Illahi AyefNo ratings yet

- Article ContentDocument10 pagesArticle ContentRicardo Muñoz PérezNo ratings yet

- Practical Manual of Processing Stool Samples For Diagnosis of ChildhoodDocument44 pagesPractical Manual of Processing Stool Samples For Diagnosis of ChildhoodНіна ЖеребкоNo ratings yet

- Penggunaan APDDocument9 pagesPenggunaan APDNurulfitrahhafidNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Anesthesia - 2007 - CATCHPOLE - Patient Handover From Surgery To Intensive Care Using Formula 1 Pit Stop andDocument9 pagesPediatric Anesthesia - 2007 - CATCHPOLE - Patient Handover From Surgery To Intensive Care Using Formula 1 Pit Stop andkowaopfdlfzfwnispxNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Breast 2020 04 006Document9 pages10 1016@j Breast 2020 04 006Alberto AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Dfa 7 30079 PDFDocument8 pagesDfa 7 30079 PDFfakhrul arifinNo ratings yet

- Impact of The COVID-19 PandemicDocument10 pagesImpact of The COVID-19 PandemicDiana MateiNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Part 1 Hipec CrsDocument19 pagesGuidelines Part 1 Hipec CrsNaty Barrios LaraNo ratings yet

- How We Do It Implementing A Virtual, Multi-Institutional Collaborative Education Model For The COVID19 Pandemic and BeyondDocument5 pagesHow We Do It Implementing A Virtual, Multi-Institutional Collaborative Education Model For The COVID19 Pandemic and BeyondMinda SariNo ratings yet

- Exemplo de Um Artigo Focus GroupDocument10 pagesExemplo de Um Artigo Focus Grouplindaflor13No ratings yet

- WHO Consolidated Guideline On TB Module 1 PreventionDocument60 pagesWHO Consolidated Guideline On TB Module 1 PreventionDavid DwiputeraNo ratings yet

- Advance Epidemiology Assignment. RumanaDocument24 pagesAdvance Epidemiology Assignment. RumanaRumana Sharmin ChandraNo ratings yet

- Ebm 4Document248 pagesEbm 4Delelegn EmwodewNo ratings yet

- Role of Immersive Technologies in Health Care EducationDocument9 pagesRole of Immersive Technologies in Health Care EducationOmoyemi OgunsusiNo ratings yet

- Gajadi 5. Rapid Implementation of Teledentistry During The Covid-19 LockdownDocument5 pagesGajadi 5. Rapid Implementation of Teledentistry During The Covid-19 LockdownIndah VitasariNo ratings yet

- Y. AL HashmiDocument11 pagesY. AL HashmiAzam alausyNo ratings yet

- Teleorthodontics in Covid Era Continuing Treatment Through Remote MonitoringDocument3 pagesTeleorthodontics in Covid Era Continuing Treatment Through Remote MonitoringInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Dal NH 22-21 PDFDocument16 pagesDal NH 22-21 PDFkissa khadija derricoNo ratings yet

- Expert Consensus Statements For The Management of COVID-19-related Acute Respiratory Failure Using A Delphi MethodDocument17 pagesExpert Consensus Statements For The Management of COVID-19-related Acute Respiratory Failure Using A Delphi MethodnicolasNo ratings yet

- TB Costing GuidelinesDocument134 pagesTB Costing GuidelinesanupamaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan ArticleDocument5 pagesPakistan ArticleSaifuddinNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Profnurs 2020 09 012Document19 pages10 1016@j Profnurs 2020 09 012Hafidz Ma'rufNo ratings yet

- 6882 27608 3 PB 2Document7 pages6882 27608 3 PB 2Zaeem KhalidNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Family Liaison Officer (FLO) Role During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument25 pagesEvaluation of The Family Liaison Officer (FLO) Role During The COVID-19 Pandemicaqsha.adamhNo ratings yet

- Focused Liquid Ultrasonography in Dropsy Protocol For Quantitative Assessment of Subcutaneous EdemaDocument12 pagesFocused Liquid Ultrasonography in Dropsy Protocol For Quantitative Assessment of Subcutaneous EdemaLex X PabloNo ratings yet

- Znab259 007Document2 pagesZnab259 007Sofyana enumbiNo ratings yet

- Best Practice Recommendations For Implementing Digital PathologyDocument38 pagesBest Practice Recommendations For Implementing Digital Pathologyjsuh00712No ratings yet

- Telehealth: A Balanced Look at Incorporating This Technology Into PracticeDocument5 pagesTelehealth: A Balanced Look at Incorporating This Technology Into PracticeAlejandro CardonaNo ratings yet

- Wong2022 Article CriticalCareUltrasoundDocument3 pagesWong2022 Article CriticalCareUltrasoundA. RaufNo ratings yet

- The DAMPen-D StudyDocument12 pagesThe DAMPen-D StudychimansqmNo ratings yet

- The Incidence of Peripheral IntravenousDocument5 pagesThe Incidence of Peripheral IntravenousAlvin Josh CalingayanNo ratings yet

- Single Port Versus Multi Port Totally.26Document8 pagesSingle Port Versus Multi Port Totally.26milo starkNo ratings yet

- Comparative Health Technology Assessment of Robotic-AssistedDocument9 pagesComparative Health Technology Assessment of Robotic-AssistedDanica SavićNo ratings yet

- Adapting To The Impact of COVID 19 Sharing Stories Sharing PracticeDocument5 pagesAdapting To The Impact of COVID 19 Sharing Stories Sharing PracticeNailis Sa'adahNo ratings yet

- European Association For Osseointegration Delphi Study On The Trends in Implant Dentistry in Europe For The Year 2030Document11 pagesEuropean Association For Osseointegration Delphi Study On The Trends in Implant Dentistry in Europe For The Year 2030Andrea LopezNo ratings yet

- A Care Bundle For Pressure Ulcer Treatment inDocument8 pagesA Care Bundle For Pressure Ulcer Treatment inSuryo Prasetyo AjiNo ratings yet

- It Wasn't Raining When Noah Built The ArkDocument4 pagesIt Wasn't Raining When Noah Built The ArkocramusNo ratings yet

- Acad Dermatol Venereol - 2021 - Balato - Patch Test Informed Consent Form Position Statement by European Academy ofDocument6 pagesAcad Dermatol Venereol - 2021 - Balato - Patch Test Informed Consent Form Position Statement by European Academy ofmaituuyen1997No ratings yet

- Nosocomial Infection Control ModuleDocument72 pagesNosocomial Infection Control Modulep1843dNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Hospital-Acquired Infections A Practical Guide 2nd EditionDocument72 pagesPrevention of Hospital-Acquired Infections A Practical Guide 2nd EditionAndreah YoungNo ratings yet

- 11 Case 4 DOHDocument1 page11 Case 4 DOHJey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- Clinical Cases Oral Cavity AnswersDocument39 pagesClinical Cases Oral Cavity AnswersJey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- 4a Lomongo Case 2Document8 pages4a Lomongo Case 2Jey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- Internal Medicine - Guazon Case Disclosure: Important Legal InformationDocument6 pagesInternal Medicine - Guazon Case Disclosure: Important Legal InformationJey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- 4a Lomongo Case 2Document8 pages4a Lomongo Case 2Jey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- AbruptioDocument1 pageAbruptioJey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- Bone TumorsDocument5 pagesBone TumorsJey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- Research ReportDocument4 pagesResearch ReportJey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- 2.C. Autoimmune and Inflammatory DisordersDocument22 pages2.C. Autoimmune and Inflammatory DisordersJey Gee DeeNo ratings yet

- Term Paper Conflict ManagmentDocument3 pagesTerm Paper Conflict Managmentmahrukhgull100% (2)

- Eo On BhertsDocument3 pagesEo On BhertsCharlene MiguelNo ratings yet

- Reso-17-2020 Eo BhertDocument2 pagesReso-17-2020 Eo BhertAnnie IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Kajian Pustaka: Keselamatan Kerja Dan Faktor Risiko Kesehatan Tenaga Kesehatan Pada Pandemi COVID-19Document9 pagesKajian Pustaka: Keselamatan Kerja Dan Faktor Risiko Kesehatan Tenaga Kesehatan Pada Pandemi COVID-19ninesuNo ratings yet

- Pharma ListDocument124 pagesPharma Listcrmassociates.financeNo ratings yet

- Service UpdatesDocument6 pagesService Updateslouis soklouNo ratings yet

- Ane Publish Ahead of Print 10.1213.ane.0000000000005043Document13 pagesAne Publish Ahead of Print 10.1213.ane.0000000000005043khalisahnNo ratings yet

- Q4 English 8 - Module 3Document31 pagesQ4 English 8 - Module 3Sarahglen Ganob Lumanao100% (1)

- Face Masks: Source Control CDC RecommendationsDocument5 pagesFace Masks: Source Control CDC RecommendationsHoonchyi KohNo ratings yet

- Bex Im Co Health Ppe CatalogueDocument23 pagesBex Im Co Health Ppe CatalogueSamantha KabirNo ratings yet

- CDC Streamlines COVID-19 GuidanceDocument9 pagesCDC Streamlines COVID-19 GuidanceJessica A. BotelhoNo ratings yet

- SOLN-MS-ST-PBD-BA101-0036 REV0 - Method Statement For Typical Structural and Superficial Concrete Repair of Defects 0-SPI-B-Approved WC 0Document20 pagesSOLN-MS-ST-PBD-BA101-0036 REV0 - Method Statement For Typical Structural and Superficial Concrete Repair of Defects 0-SPI-B-Approved WC 0leepatrickbanezNo ratings yet

- Metal Bollards Installation Risk AssessmentDocument7 pagesMetal Bollards Installation Risk AssessmentEldhose VargheseNo ratings yet

- Project Planning 19mba003 (N 95 Manufacturing)Document11 pagesProject Planning 19mba003 (N 95 Manufacturing)Adarsh JainNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Basic Clinical Lab Competencies For Respiratory Care An Integrated Approach 5th Edition WhiteDocument9 pagesTest Bank For Basic Clinical Lab Competencies For Respiratory Care An Integrated Approach 5th Edition WhiteGeorge Rogers100% (41)

- WSI Catalogue 2023Document51 pagesWSI Catalogue 2023LailyNo ratings yet

- EAPP RomeoDocument15 pagesEAPP RomeoRomeo GasparNo ratings yet

- Particle Respirator 8000, N95: An Economical Solution For Light Duty or Short Duration ApplicationsDocument2 pagesParticle Respirator 8000, N95: An Economical Solution For Light Duty or Short Duration ApplicationsMichael TadrosNo ratings yet

- Disaster Management AssignmentDocument8 pagesDisaster Management AssignmentAdarsh RNo ratings yet

- Nursing Admin - CBAHI - JCI Handbook - 31 October 2020Document26 pagesNursing Admin - CBAHI - JCI Handbook - 31 October 2020fahed28ksaNo ratings yet

- Regulations, Part 84 (42 CFR 84) .: Department of Health & Human ServicesDocument9 pagesRegulations, Part 84 (42 CFR 84) .: Department of Health & Human ServicesPROYECTOS JGNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region Iv-A Calabarzon Schools Division of Rizal Jalajala Sub-Office Sipsipin Elementary SchoolDocument12 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region Iv-A Calabarzon Schools Division of Rizal Jalajala Sub-Office Sipsipin Elementary SchoolnanethangelesNo ratings yet

- 3M 8210 Brochure-2015Document4 pages3M 8210 Brochure-2015Michael TadrosNo ratings yet

- NCM 109 SkillsDocument7 pagesNCM 109 SkillsMae Arra Lecobu-anNo ratings yet

- N95 Vs FFP3 & FFP2 Masks - What's The DifferenceDocument1 pageN95 Vs FFP3 & FFP2 Masks - What's The DifferenceRobert SmoothopNo ratings yet

- National Kidney and Transplant Institute: East Avenue, Quezon CityDocument1 pageNational Kidney and Transplant Institute: East Avenue, Quezon CityLizette Oribe ReyNo ratings yet

- Donning and Doffing ChecklistDocument7 pagesDonning and Doffing ChecklistMary Cueva0% (1)

- Proof That Face Masks Do More Harm Than Good v2Document41 pagesProof That Face Masks Do More Harm Than Good v2WalterHachmannNo ratings yet

- Jsa - JSWDocument3 pagesJsa - JSWRahul ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- JSA For SRP Instolation and DismentlingDocument17 pagesJSA For SRP Instolation and DismentlingShekh BabulNo ratings yet

- Face Masks Pose Serious Risk To Healthy People. No Scientific Evidence That Masks Are Effective Against COVID-19 Transmission, Neurosurgeon SaysDocument4 pagesFace Masks Pose Serious Risk To Healthy People. No Scientific Evidence That Masks Are Effective Against COVID-19 Transmission, Neurosurgeon SaysDoug TrudellNo ratings yet