Professional Documents

Culture Documents

GVA and GDP Difference

Uploaded by

AmitOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

GVA and GDP Difference

Uploaded by

AmitCopyright:

Available Formats

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) on Friday released the economic growth data for

the first quarter (Q1, or April to June) of the current financial year (2019-20, or

FY20). A disappointing number was widely expected, especially after the 5.8%

growth in Q4 of FY19, and the wave of bad news such as falling sales of

automobiles and everyday consumables even so, the official GDP data of just 5%

came as a shock to many.

Real vs Nominal Growth

At 5%, the real GDP growth rate has hit a six-year low (see Chart 1). Real GDP

growth rate is a derived figure it is arrived at by subtracting the inflation rate from

the nominal GDP growth rate that is growth rate calculated at current prices. What

is more worrying is the deceleration in the nominal GDP growth, which has been

pegged at 8% for Q1. For perspective, it should be noted that the Union Budget,

presented on July 5, had expected a nominal growth of 12%. The idea was that

with a 12% nominal growth and 4% inflation rate, real GDP would be 8%.

At 8% nominal growth, all calculations real GDP and tax revenues etc. go haywire.

An 8% nominal growth is unusually low; just once has nominal growth fallen to this

level in both the current GDP series (with a base year of 2011-12) and the past

GDP series (with the base year of 2004-05). And that was in the wake of the global

financial crisis in 2009.

GVA vs GDP

There are two main ways in which the CSO estimates economic growth. One is from

the supply side that is, by mapping the value-added (in rupee terms) by the various

sectors in the economy. The sectors are broadly divided into Agriculture, Industry

and Services, and all workers in the economy fall into one or the other category.

There are sub-categories too Industry, for example, has Manufacturing,

Construction, Mining & Quarrying, etc. When all the value-added is totalled, we get

the Gross Value Added (GVA) in the economy. In other words, GVA tracks the

income generated for all the workers in the economy.

The GDP is arrived at from the demand side. It is calculated by mapping the

expenditure made by different categories of spenders. Broadly speaking, there are

four sources of expenditure in an economy namely, private consumption,

government consumption, business investments, and net exports (exports minus

imports). Because the GDP maps final expenditure, it includes both taxes and

subsidies that the government receives and gives. This component, net taxes, is

the difference between GVA and GDP.

Typically, GDP is a good measure when you want to compare India with another

economy, while GVA is better to compare different sectors within the economy. GVA

is more important when looking at quarterly growth data, because quarterly GDP is

arrived at by apportioning the observed GVA data into different spender categories.

The supply-side story

The GVA in Q1 is pegged at 4.9%. Such a low level of GVA suggests that producers

are not adding enough value in other words, their income growth is low. As Chart 2

shows, growth in all three sectors has declined, but most of the decline is in

Agriculture and Industry. Within Industry, Manufacturing has seen a spectacular

collapse. Other sub-sectors of Industry such as Mining & Quarrying and

Construction too, have slumped over the past five quarters.

These two sectors Agriculture and Industry not only employ the largest number of

people, but also have the maximum potential to create new jobs. Stagnant

Agriculture and Industry imply that a bulk India's poorest and less educated

workforce is either not getting jobs, or not seeing their incomes grow. And they

can’t shift to the better-paying Services sector because of the deficiency in skills.

The demand-side story

The GVA weakness shows up on the demand side (Chart 3). Private consumption,

which accounts for over 55% of GDP, has grown by just 3.14%. The reason why

private demand has collapsed is that the bulk of India's labour force is not earning

enough to spend more.

The other big GDP component business investments (which accounts for 32% of

GDP) has grown by just 4.04%. Businesses are not investing because they are

either in the process of deleveraging (getting rid of excess loans) or stuck with

unsold inventories. The only spender that has grown better than expected is the

government.

What the numbers imply

Firstly, the growth trajectory suggests there is more pain ahead. According to an

analysis by State Bank of India, when GDP grew by 8% in Q1 of FY19, 70% of the

leading indicators such as car sales showed acceleration. In this quarter, only 35%

of these indicators showed acceleration, and GDP grew by 5%. For Q2 (July to

September), only 24% indicators show acceleration.

Secondly, since the release, GDP growth rate forecasts for the current year have

been dialed down yet again. Most observers expected a real GDP growth rate of

somewhere between 5.4% and 6.4% for Q1. Now, SBI pegs the full-year growth at

6.1%, ICICI Securities at 6.3%, and Pronab Sen, former Chief Statistician, pegs it

at 5.5%. Roughly six months ago, most estimates for FY20 were around 7.5%.

Thirdly, such weak growth implies that the government's fiscal deficit figures are

likely to be breached. Lastly, since weak growth will lead to lower tax revenues, the

government is likely to struggle if it wants to push up growth by spending on its

own.

You might also like

- Management Accountant June 2018Document124 pagesManagement Accountant June 2018ABC 123No ratings yet

- P - Name Orgnization Turn - Over AddressDocument24 pagesP - Name Orgnization Turn - Over AddressAmitNo ratings yet

- Economics IA MACRODocument7 pagesEconomics IA MACROAayush KapriNo ratings yet

- Indian Economy FinalDocument24 pagesIndian Economy FinalArkadyuti PatraNo ratings yet

- GDP (Gross Domestic Product) AnalysisDocument5 pagesGDP (Gross Domestic Product) AnalysisprashantNo ratings yet

- GDP Growth Drivers in PakistanDocument6 pagesGDP Growth Drivers in PakistannanabirjuNo ratings yet

- What is GDP? Understanding GDP, GVA, economic growthDocument4 pagesWhat is GDP? Understanding GDP, GVA, economic growthNivedita RajeNo ratings yet

- Balance of Payments: 2. InflationDocument3 pagesBalance of Payments: 2. InflationKAVVIKANo ratings yet

- Indian Economy Slowdown Causes and EffectsDocument8 pagesIndian Economy Slowdown Causes and EffectsGopinath KNo ratings yet

- Present Economic SlowdownDocument8 pagesPresent Economic SlowdownGopinath KNo ratings yet

- Present Indian Economy SlowdownDocument8 pagesPresent Indian Economy SlowdownGopinath KNo ratings yet

- National Income in IndiaDocument5 pagesNational Income in IndiaSharmila tonyNo ratings yet

- GDP Fy14 Adv Est - 7 Feb 2014Document4 pagesGDP Fy14 Adv Est - 7 Feb 2014mkmanish1No ratings yet

- Vision: Personality Test Programme 2019Document5 pagesVision: Personality Test Programme 2019sureshNo ratings yet

- GDP at 7.8% Doesn't Reflect Current Underlying Momentum of Indian EconomyDocument2 pagesGDP at 7.8% Doesn't Reflect Current Underlying Momentum of Indian EconomyManas RaiNo ratings yet

- How Does The Central Statistics Office Calculate GDP?: Thu, Jun 02 2016. 04 00 AM ISTDocument5 pagesHow Does The Central Statistics Office Calculate GDP?: Thu, Jun 02 2016. 04 00 AM ISTSankit MohantyNo ratings yet

- IE - Article ReviewDocument8 pagesIE - Article Review541ANUDEEP VADLAKONDANo ratings yet

- India's Economy in 2018-19: Key HighlightsDocument59 pagesIndia's Economy in 2018-19: Key HighlightsprashantNo ratings yet

- Reliance Communications LTDDocument29 pagesReliance Communications LTDShafia AhmadNo ratings yet

- India's Economic Position Despite Slowdown in GrowthDocument21 pagesIndia's Economic Position Despite Slowdown in GrowththakursahbNo ratings yet

- Economic Survey 2019Document11 pagesEconomic Survey 2019The Indian ExpressNo ratings yet

- Connecting Macros: Relation Between GDP and Covid 19Document9 pagesConnecting Macros: Relation Between GDP and Covid 19Zea ZakeNo ratings yet

- The Market Call (July 2012)Document24 pagesThe Market Call (July 2012)Kat ChuaNo ratings yet

- Philippines Misses GDP Growth Target For 2019Document4 pagesPhilippines Misses GDP Growth Target For 2019Joan AbieraNo ratings yet

- Mets September 2010 Ver4Document44 pagesMets September 2010 Ver4bsa375No ratings yet

- India Synopsis-UpdatedDocument33 pagesIndia Synopsis-UpdatedAbhishek pathangeNo ratings yet

- First Advance Estimates of India's GDP Out - What Are They, and What Do The Data Show - Explained News - The Indian ExpressDocument7 pagesFirst Advance Estimates of India's GDP Out - What Are They, and What Do The Data Show - Explained News - The Indian Expressnamankale2406No ratings yet

- Course: Macro Economics Course Code: Bmt6111 SEMESTER: Tri Semester'2019-20Document9 pagesCourse: Macro Economics Course Code: Bmt6111 SEMESTER: Tri Semester'2019-20Gopinath KNo ratings yet

- Explained - How To Read Q1 GDP Data - Explained News, The Indian ExpressDocument11 pagesExplained - How To Read Q1 GDP Data - Explained News, The Indian ExpresshabeebNo ratings yet

- Indian EconomyDocument6 pagesIndian EconomyKhushboo KohadkarNo ratings yet

- State of EconomyDocument21 pagesState of EconomyHarsh KediaNo ratings yet

- Indian EconomyDocument37 pagesIndian EconomyDvitesh123No ratings yet

- Eic AnalysisDocument17 pagesEic AnalysisJaydeep Bairagi100% (1)

- Report on Indian macroeconomics and banking sector outlookDocument17 pagesReport on Indian macroeconomics and banking sector outlookpratiknkNo ratings yet

- Task 3 GDPDocument9 pagesTask 3 GDPAishwaryaNo ratings yet

- Therefore GDP C+ G+ I + N ExDocument10 pagesTherefore GDP C+ G+ I + N Exyashasheth17No ratings yet

- India's GDP Analysis For The Last 3 Years (2019-2021)Document4 pagesIndia's GDP Analysis For The Last 3 Years (2019-2021)justin joyNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Economy Group AssignmentDocument25 pagesMalaysian Economy Group Assignmentyunfan yNo ratings yet

- Philippines GDP Growth Drops to 8-Year Low of 5.9% in 2019Document7 pagesPhilippines GDP Growth Drops to 8-Year Low of 5.9% in 2019Mirai KuriyamaNo ratings yet

- INSTA Economic Survey2019 20 Volume 2Document76 pagesINSTA Economic Survey2019 20 Volume 2Sri Harsha DannanaNo ratings yet

- Task 4 - Abin Som - 21FMCGB5Document8 pagesTask 4 - Abin Som - 21FMCGB5Abin Som 2028121No ratings yet

- Covid-19 impact on Indian economyDocument70 pagesCovid-19 impact on Indian economyKushal JesraniNo ratings yet

- Union Budget 2019-20: July 5, 2019Document19 pagesUnion Budget 2019-20: July 5, 2019majhiajitNo ratings yet

- Union Budget Report 2019 20 PDFDocument19 pagesUnion Budget Report 2019 20 PDFok2No ratings yet

- Project KMFDocument96 pagesProject KMFLabeem SamanthNo ratings yet

- Investment Growth Factors Pakistan EconomyDocument5 pagesInvestment Growth Factors Pakistan EconomyaoulakhNo ratings yet

- ECONOMIC ANALYSIS DaburDocument5 pagesECONOMIC ANALYSIS DaburEKANSH DANGAYACH 20212619No ratings yet

- GDPDocument5 pagesGDPKatta AshishNo ratings yet

- Monthly Economic ReviewDocument19 pagesMonthly Economic ReviewВладимир СуворовNo ratings yet

- GDP Debate UPSC Notes GS IIIDocument3 pagesGDP Debate UPSC Notes GS IIIAdil Khan PathanNo ratings yet

- Eco AssignmentDocument33 pagesEco Assignmentmahishah2402No ratings yet

- Data Analysis & InterpretationsDocument40 pagesData Analysis & InterpretationsRiyaz AliNo ratings yet

- Japan_Economic_ReportDocument11 pagesJapan_Economic_Reportcandidwriters92No ratings yet

- Monthly Review of Indian Economy: April 2011Document36 pagesMonthly Review of Indian Economy: April 2011Rahul SainiNo ratings yet

- Economy: Cse Prelims 2020: Value Addition SeriesDocument83 pagesEconomy: Cse Prelims 2020: Value Addition SeriesKailash KhaliNo ratings yet

- India GDP Growth Slows to 7.8Document4 pagesIndia GDP Growth Slows to 7.8Pandit Here Don't FearNo ratings yet

- Role of Minerals in The National EconomicsDocument28 pagesRole of Minerals in The National Economicspt naiduNo ratings yet

- Monthly - May - 2015Document56 pagesMonthly - May - 2015Akshaj ShahNo ratings yet

- Group 3G - MEM ReportDocument21 pagesGroup 3G - MEM ReportNishant GuptaNo ratings yet

- Economic Slowdown and Macro Economic PoliciesDocument38 pagesEconomic Slowdown and Macro Economic PoliciesRachitaRattanNo ratings yet

- RBI's New GDP Template: The 12 Enablers of India's Growth MakeoverDocument4 pagesRBI's New GDP Template: The 12 Enablers of India's Growth MakeoverSouvik BoseNo ratings yet

- Reflections on the Economy of Rwanda: Understanding the Growth of an Economy at War During the Last Thirty YearsFrom EverandReflections on the Economy of Rwanda: Understanding the Growth of an Economy at War During the Last Thirty YearsNo ratings yet

- Note On Single Window Clearance System 1. BackgroundDocument2 pagesNote On Single Window Clearance System 1. BackgroundAmitNo ratings yet

- Contact Details of RTAsDocument21 pagesContact Details of RTAsRonny DasNo ratings yet

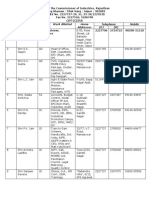

- Sector Company Name Location Product Status IP Officer Category S. No.1 Proposed Inv Prop Dir Emp Prop Ind Emp Proposal Receiving DateDocument25 pagesSector Company Name Location Product Status IP Officer Category S. No.1 Proposed Inv Prop Dir Emp Prop Ind Emp Proposal Receiving DateAmitNo ratings yet

- Reduction in The Procedure of Application For Obtaining Clearances Within The Stipulated Time PeriodDocument1 pageReduction in The Procedure of Application For Obtaining Clearances Within The Stipulated Time PeriodAmitNo ratings yet

- Bystander ApathyDocument1 pageBystander ApathyAmitNo ratings yet

- Note English - One Stop ShopDocument1 pageNote English - One Stop ShopAmitNo ratings yet

- Rajasthan Summit - LayoutDocument14 pagesRajasthan Summit - LayoutAmitNo ratings yet

- S. No. Work Allocation Coordinators of CII Tentative Deployment Contact NumberDocument1 pageS. No. Work Allocation Coordinators of CII Tentative Deployment Contact NumberAmitNo ratings yet

- RR15 Volunteer Orientation FinalDocument24 pagesRR15 Volunteer Orientation FinalAmitNo ratings yet

- Urban Wastewater ManagementDocument6 pagesUrban Wastewater ManagementAmitNo ratings yet

- Resurgent Rajasthan LayoutDocument4 pagesResurgent Rajasthan LayoutAmitNo ratings yet

- DataDocument249 pagesDataAmitNo ratings yet

- Pre-Reform: ComplianceDocument1 pagePre-Reform: ComplianceAmitNo ratings yet

- Officers List Commissioner IndustriesDocument4 pagesOfficers List Commissioner IndustriesAmitNo ratings yet

- Sewerage Policy of Rajasthan-Vision 2030: BackgroundDocument6 pagesSewerage Policy of Rajasthan-Vision 2030: BackgroundAmitNo ratings yet

- RR15 Volunteer Orientation 07.11.2015Document45 pagesRR15 Volunteer Orientation 07.11.2015AmitNo ratings yet

- Brief Note On Jaipur Metro Rail Project: Phase Length (KMS) Cost (Rs. in Crore)Document7 pagesBrief Note On Jaipur Metro Rail Project: Phase Length (KMS) Cost (Rs. in Crore)AmitNo ratings yet

- Urban Transport Group - French Delegate - 7th July 2014Document34 pagesUrban Transport Group - French Delegate - 7th July 2014AmitNo ratings yet

- Snapshot of RIPS - 2014 in A Grid FormDocument3 pagesSnapshot of RIPS - 2014 in A Grid FormAmitNo ratings yet

- Rajasthan MSME Policy 2015: PreambleDocument17 pagesRajasthan MSME Policy 2015: PreambleAmitNo ratings yet

- Advantage Rajasthan - Auto - V0.3Document11 pagesAdvantage Rajasthan - Auto - V0.3AmitNo ratings yet

- A Brief Note On The Investment Climate in Rajasthan For IndustryDocument4 pagesA Brief Note On The Investment Climate in Rajasthan For IndustryAmitNo ratings yet

- One To One Meeting FormatDocument1 pageOne To One Meeting FormatAmitNo ratings yet

- Acknowledgment FormDocument1 pageAcknowledgment FormAmitNo ratings yet

- Security Audit SOWDocument2 pagesSecurity Audit SOWAmitNo ratings yet

- Vba Macros Simplified For BeginnersDocument60 pagesVba Macros Simplified For BeginnersAmitNo ratings yet

- Proposal For Conducting Website Security Audit of Invest Rajasthan Website Application.Document13 pagesProposal For Conducting Website Security Audit of Invest Rajasthan Website Application.AmitNo ratings yet

- Mopani District MunicipalityDocument242 pagesMopani District MunicipalityAndy MposulaNo ratings yet

- Wesport Economic Impact Report Full Report Web VersionDocument40 pagesWesport Economic Impact Report Full Report Web VersionlawrelatedNo ratings yet

- A Proposed Representative Sampling MethodologyDocument12 pagesA Proposed Representative Sampling MethodologyNovaSribdNo ratings yet

- Mohanty - Fiscal Deficit and Economic GrowthDocument25 pagesMohanty - Fiscal Deficit and Economic GrowthAnurag DharNo ratings yet

- SN06193Document15 pagesSN06193Imran KhanNo ratings yet

- Indian Economy Key Concepts Sixth Edition English eBook PDFDocument89 pagesIndian Economy Key Concepts Sixth Edition English eBook PDFmildred.gaydosh171No ratings yet

- Subhash Dey's IED Textbook 2024-25 Sample PDFDocument46 pagesSubhash Dey's IED Textbook 2024-25 Sample PDFravinderd2003No ratings yet

- Indian EconomyDocument260 pagesIndian EconomyKomal SinghNo ratings yet

- Study Id63682 Meat and Seafood Industries in IndiaDocument35 pagesStudy Id63682 Meat and Seafood Industries in IndiaParv PandyaNo ratings yet

- National IncomeDocument22 pagesNational IncomeVishnu VardhanNo ratings yet

- FY 21-22 - MFIN India Microfinance ReviewDocument92 pagesFY 21-22 - MFIN India Microfinance Reviewletihi9143No ratings yet

- ANIMATION in Depth Study Tapspp0102Document116 pagesANIMATION in Depth Study Tapspp0102AlvinTiteNo ratings yet

- AP Statistical Abstract 2019Document723 pagesAP Statistical Abstract 2019Vivek Karthik100% (1)

- Chapter 05 Industries and PowerDocument64 pagesChapter 05 Industries and Powerraghunandhan.cvNo ratings yet

- BCG Melbourne As A Global Cultural Destination Summary For CV WebsiteDocument56 pagesBCG Melbourne As A Global Cultural Destination Summary For CV WebsiteirzaNo ratings yet

- National Account Statistics: Hersch SahayDocument37 pagesNational Account Statistics: Hersch SahayShivam ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- GDP Gva GapDocument20 pagesGDP Gva GapAnkita Kumari 5007No ratings yet

- INSTA March 2021 Current Affairs Quiz CompilationDocument66 pagesINSTA March 2021 Current Affairs Quiz CompilationAnamika BeheraNo ratings yet

- Ppt. N.I Calculation NumericalsDocument162 pagesPpt. N.I Calculation NumericalsHusain IraniNo ratings yet

- PG DissertationDocument39 pagesPG Dissertationavikalmanitripathi2023No ratings yet

- CBSE Class-12 Economics Important Questions - Macro Economics 02 National Income AccountingDocument10 pagesCBSE Class-12 Economics Important Questions - Macro Economics 02 National Income AccountingSachin DevNo ratings yet

- Karnataka Economic Survey 2021-22-m2 - Eng - FinalDocument895 pagesKarnataka Economic Survey 2021-22-m2 - Eng - FinalsupreethsdNo ratings yet

- Support Material For Economics, Class XII (2022-23), KVS Ernakulum RegionDocument325 pagesSupport Material For Economics, Class XII (2022-23), KVS Ernakulum RegionKashvi ChakrawalNo ratings yet

- Free Sample Study Id42056 Waste Management and Recycling in The UkDocument60 pagesFree Sample Study Id42056 Waste Management and Recycling in The UkMINSAFE Fin-26thNo ratings yet

- Economic Review Vol 2 EngDocument457 pagesEconomic Review Vol 2 Engmeghasunil24No ratings yet

- Value Added Statement Questions and AnswersDocument2 pagesValue Added Statement Questions and AnswersPeter ImageNo ratings yet

- Agriculture-and-Allied-Industries - Jan 2021Document39 pagesAgriculture-and-Allied-Industries - Jan 2021Anand KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Highlights of Agriculture Ministry Annual Report 2022-23 Lyst3890Document55 pagesHighlights of Agriculture Ministry Annual Report 2022-23 Lyst3890Sumit SurkarNo ratings yet

- National Income (Notes) IMBADocument27 pagesNational Income (Notes) IMBASubham .MNo ratings yet

- Niti Annual Report-2014-15Document217 pagesNiti Annual Report-2014-15Prem SagarNo ratings yet