Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Takeaways For Weeks 06-07 The Essence of Research in The Study of Rizal

Uploaded by

Leiann PongosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Takeaways For Weeks 06-07 The Essence of Research in The Study of Rizal

Uploaded by

Leiann PongosCopyright:

Available Formats

GE1804

TAKEAWAYS FOR WEEKS 06-07

The Essence of Research in the Study of Rizal

The study of the life and works of Jose Rizal is a result of decades of research about Jose Rizal, as well as

the study about the conditions of the Philippines during the Spanish Colonization. In essence, the life of

Jose Rizal and the country's social conditions during the Spanish Colonization are inextricable. Since the

term "research" has been mentioned, let us define what it is. Research is a systematic method of

investigating and studying materials to establish facts and conclusions. Thus, we establish truths and

information based on concrete, substantial evidence.

One (1) way of obtaining information is through an interview. An interview is the method of obtaining

information through an interchange of questions and answers. The researcher personally asks someone

about something, which is reciprocated with information, which can be scrutinized later when corroborated

with other pieces of evidence obtained in other means.

The Philippines During the Spanish Colonization

The Philippines, before it was colonized, had been a thriving civilization, with its own established cultures,

traditions, ways of living, religions, and laws. This was also when we had established trade relations with

nearby countries, such as China and Indonesia, among others. For the Chinese, we have bartered pearls

and other produce for porcelain, jade, and silk, among others being carried in their junk (i.e., trading boat).

Each barangay had a datu, the leader, and prime defender of the community. These leaders may not be

accommodating towards outsiders, but they were not dictators (as narrated by Filomeno Aguilar).

However, when Spain set foot on our native soil, the pre-colonial lifestyle began to dwindle except in some

parts of Mindanao. During this time, the colonial government implemented taxation onto the colonized

natives and their trade partners. The taxation system can be seen in its established Casta. The casta is

divided into sections, which dictated their tax value.

Peninsulares

Tax-Free Americano

Insulares

Mestizo de Español

Variable Tax Mestizo de Bombay

Mestizaje

Value Mestizo de Sangley

Tornatras

Quadrupled

Sangley

Tax Value

Base Tax Indio

Value Negrito

Filipinos and the Negritos pay only the base value, making them the only ones who pay the minimum

amount. The Sangleys are the pure-blooded Chinese who lived in the country. They pay to quadruple the

base amount because of their business and labor skills. The mestizaje is the racially ambiguous people

who paid tax based on their lineage and status. As an example, if a Sangley businessman had a mestiza

de Sangley, daughter, the daughter would pay half as much as her father's tax rate. However, should the

03 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 1 of 4

GE1804

mestiza daughter marry an Americano, who paid zero tax alongside the insulares and the peninsulares,

her tax would be removed altogether.

However, the treatment she would receive from the masses would remain the same. Indians also lived in

the country, but they were not part of the casta. Below the blancos (i.e., the "tax-free" casta) were the

mestizaje, whose casta were based on their parentage. Mixed blood by nature, their status often fluctuated,

and their taxes were the same as the indios (except for the mestizo de Sangleys). Of the four (4) mestizos,

the Tornatras were the lowest because they had more than two (2) racial parentages, hinting that the

Tornatras had the most intermingling of races.

If we are to look at them today, we can use the following celebrities and heroes as examples:

NAME IMAGE HERITAGE(S) CASTA

Paul Patrick Filipino-German Tornatras

Gruenberg (possibly multiracial

"Polo Ravales" to his Filipino side)

Source: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1066382/bio

Trinidad Spanish (born in the Insulares (Mestizo

Hermenigildo Pardo Philippines) de Español in some

de Tavera references)

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinidad_Pardo_de_Tavera

Kristina Bernadette Filipino-Chinese Mestizo de Sangley

Aquino

"Kris Aquino"

Source: https://mydramalist.com/people/20452-kris-

aquino

Cesar Manhilot Filipino Indio

"Cesar Montano"

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cesar_Montano

03 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 2 of 4

GE1804

Ramon Bagatsing III Filipino-Indian Mestizo de Bombay

"Raymond (surname Filipinized

Bagatsing" from Indian Bhagat

Singh)

Source:

http://www.showbizportal.net/2011/10/raymond-

bagatsing-assailed-ex-wife-cora.html

Jose Protacio Rizal Multiracial Tornatras (however,

Mercado y Alonso he was considered

Realonda a mestizo de

Sangley)

Source:

https://www.manilatimes.net/2019/12/30/news/top-

stories/jose-rizals-prowess-in-sports-legendary/668654/

Along with the establishment of the casta was the implementation of the polo and bandala. Polo is the

forced labor imposed upon Filipino men aged 16-60 years. They were required to do skilled labor for 40

days, which was reduced to 15 days. Filipinos can be exempted from this labor in two (2) ways:

1. They had to pay a fine (called a falla); or

2. Work until they paid their debt.

Not even death could prevent the debt from growing. If the abled men died, their unpaid debts would be

passed on to the next abled men in the family, and so on. If the able person's age was below the

requirement, yet their birthday drew close to the recruitment date, then they would render polo nonetheless.

The History of Land Ownership and Peasantry in the Philippines

During Rizal's education in the Philippines, Paciano provided ample funding for his younger brother to study

abroad. This made Rizal a member of the ilustrado, an expatriate whose sole purpose abroad was to study.

However, when Rizal arrived and settled in Europe, problems began to rise in Calamba regarding the lands

owned by his family.

The problems with agrarian ownership have been a long-standing problem in the country, which was more

evident during the Spanish Occupation. This was when the local serfs (i.e., the aliping namamahay) were

stripped of their lands by the Spaniards, who used these lands for their own. These lands were cultivated

by the same natives who were once the former owners. Such problems began to expound when friars

became the owners, particularly in Negros and Calamba. In Calamba, the Dominicans began to exploit the

natives with their ever-fluctuating tax values. This was viewed by the Calambeños as abusive and began

to argue with the abusive Dominicans -- especially when they grabbed the lands owned by the Mercados.

They at first appealed to the local government but were ignored due to the influence of the Dominicans in

the place. Thus, they prompted Rizal to conduct an investigation, whose reports would be submitted to a

local judge connected to Paciano to even the odds. However, in the end, their protestations fell onto deaf

ears.

03 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 3 of 4

GE1804

The Cavite Mutiny

The Cavite Mutiny was one (1) of the aftermaths of the civil war that erupted in Spain during Queen Isabella

II's reign. On 27 February 1767, King Carlos III of Spain ordered the complete expulsion of the sect of the

Society of Jesus (Jesuits) from Spain and all her colonies. Then Governor-General Raon tried to help the

religious order in exchange for bribes. Once the Jesuits destroyed their documents and hid all their

possessions, there was a shortage of priests when Raon died before being punished by his successor.

Then Manila archbishop Basilio Sancho de Santa Justa spearheaded the conversion and ordainment of

Filipinos into the priesthood, which was heavily opposed. This argument came to be known as the

secularization issue. Back then, news traveled slowly. When then Governor-General Carlos Maria de la

Torre was still in the country, he received a letter about his reinstatement without knowing about the civil

war in Spain. Upon his departure, his liberal program was stunted upon the sudden arrival of Rafael

Geronimo Cayetano Izquierdo. Izquierdo noted that he would rule the Philippines "with a cross in one hand

and a sword in the other".

Thus, with a strict regime, the lives of the Filipinos began to crumble. When the mutiny occurred, the

Spanish friars accused Filipino priest Jose Burgos, along with a few other secular priests, to be the

masterminds of the event, despite being truly driven by the Filipinos' desires of escaping polo in Cavite, the

"Land of the Brave". Due to the friar's influence, three (3) Filipino priests -- Mariano Gomez, Burgos, and

Jacinto Zamora -- were implicated in the trial by another fellow Filipino, Francisco Zaldua (Saldua in other

references). This event, among many others, paved the way to drive out Spain.

REFERENCES:

Aguilar, F. (1998). Elusive peasant, weak state: Sharecropping and the changing meaning of debt. In Clash of Spirits:

The History of Power and Sugar Planter Hegemony on a Visayan Island, 63-77. Quezon City: Ateneo de

Manila University Press. HD9116 P53 N42

Aguilar, F. (2016). Sugar capitalism: The divergent paths of haciendas on Negros island and the Hacienda de Calamba.

In Journal of Southeast Asian Studies

Artigas, M. C. (1996). National glories: the events of 1872 (O. D. Corpuz, Trans.). Quezon City: University of the

Philippines Press.

Rizal, J. P. (1889). La verdad para todos. In La Solidaridad, 1 (G. Fores-Galzon, Trans.). Pasig: Fundacion Santiago.

DS651 S6 1996

Roth, D. M. (1982). Church lands in the agrarian history of Tagalog region. In Philippine social history: Global trade and

local transformation (A. W. McCoy & E. de Jesus, Ed.), 131-153. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University

Press. HN713 P44

Schumacher, J. (1999). Historical introduction. In Father Jose Burgos: A documentary history with Spanish documents

and their translations, 1-32. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. DS675.8 B8 S37

Schumacher, J. (2011). The Cavite mutiny: Towards a definitive history. In Philippine Studies, 59(1), 55-81

Schumacher, J. (2011). The Burgos manifesto: The authentic text and its genuine author. In Philippine Studies, 54(2),

153-304

Wickberg, E. (1964). The Chinese mestizo in Philippine history. In Journal of Southeast Asian History, 5(1), 62-100.

New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

Wickberg, E. (2000). The Philippine Chinese before 1850. In The Chinese in Philippine Life, 1850-1898, 25-36. Quezon

City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. D666 C5W5 2000

03 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 4 of 4

You might also like

- 1L Contracts OutlineDocument10 pages1L Contracts OutlineEvangelides100% (3)

- Spanish Colonial Caste System in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesSpanish Colonial Caste System in The PhilippinesConcon FabricanteNo ratings yet

- DOJ MCL 08-006-Revised Rules Governing Philippine Citizenship Under Republic Act (Ra) 9225Document7 pagesDOJ MCL 08-006-Revised Rules Governing Philippine Citizenship Under Republic Act (Ra) 9225Angela CanaresNo ratings yet

- Rizal Disliked Chinese Reaction PaperDocument5 pagesRizal Disliked Chinese Reaction PaperSunshine Arceo86% (7)

- The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryDocument21 pagesThe Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryBigbang Forever100% (1)

- Ascendance of Chinese Mestizos in The Philippines - RZL110Document4 pagesAscendance of Chinese Mestizos in The Philippines - RZL110Adrien Joshua100% (4)

- Batis Lesson4Document2 pagesBatis Lesson4Julie Ann Co100% (1)

- Elusive Peasant Group 5Document3 pagesElusive Peasant Group 5FrancisNo ratings yet

- GRP 1 - Ascendance of Chinese MestizosDocument23 pagesGRP 1 - Ascendance of Chinese MestizosJomel Bermundo0% (1)

- Subversion of Law Enforcement Intelligence Gathering Operations (1976)Document68 pagesSubversion of Law Enforcement Intelligence Gathering Operations (1976)Regular Bookshelf0% (1)

- PTCFORDocument1 pagePTCFORDDC KonsultNo ratings yet

- The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryDocument21 pagesThe Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryBigbang ForeverNo ratings yet

- The Development of Chinese Mestizo in The PhilDocument18 pagesThe Development of Chinese Mestizo in The PhilJose Miguel RuizNo ratings yet

- Ascendance of Chinese MestizoDocument2 pagesAscendance of Chinese MestizoYll AsheilemaNo ratings yet

- Ascendance of Chinese MestizosDocument21 pagesAscendance of Chinese MestizosNICOLENAZ ENCARNACIONNo ratings yet

- Global Market and Ascendance of The MestizosDocument5 pagesGlobal Market and Ascendance of The MestizosKaezeth Jasmine AñanaNo ratings yet

- En La Vida Et Obras de Rizal Medio TerminoDocument39 pagesEn La Vida Et Obras de Rizal Medio TerminoMCCEI RADNo ratings yet

- Spaniards, Sangleys, MestizosDocument18 pagesSpaniards, Sangleys, MestizosSteve B. SalongaNo ratings yet

- Rizal Report - 19TH CenturyDocument25 pagesRizal Report - 19TH CenturyNamja PyosiNo ratings yet

- RLW RequirementDocument3 pagesRLW RequirementMarisol Plaza Nadonza80% (5)

- Customs of The Tagalogs 2Document21 pagesCustoms of The Tagalogs 2Aldrin MarianoNo ratings yet

- Elusive Peasant, Weak StateDocument5 pagesElusive Peasant, Weak StateЅєди Диԁяєш Вцвди Ҩяцтдѕ67% (6)

- Mrr2 - VenturaDocument1 pageMrr2 - VenturaJames Brian VenturaNo ratings yet

- THOUGHT PAPER - Why Counting Counts - Eva Margarita Buenaobra BSARCH3ADocument3 pagesTHOUGHT PAPER - Why Counting Counts - Eva Margarita Buenaobra BSARCH3AevaNo ratings yet

- Carlos Hilado Memorial State CollegeDocument4 pagesCarlos Hilado Memorial State CollegeTin CorderoNo ratings yet

- Ascendance of The MestizosDocument17 pagesAscendance of The MestizosMeicy ToyamaNo ratings yet

- Ascendance of Chinese MestizosDocument13 pagesAscendance of Chinese MestizosAndrea Anne RiveraNo ratings yet

- Output 5Document4 pagesOutput 5Bea Rochelle TanierlaNo ratings yet

- Lesson03 MIDTDocument8 pagesLesson03 MIDTJanna Hazel Villarino VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Rizal Midterm ReviewerDocument1 pageRizal Midterm ReviewerimdenverdenverNo ratings yet

- Nantes C5 GT2 RZL110Document3 pagesNantes C5 GT2 RZL110Mika SorredaNo ratings yet

- What Are The Writing of Jose RizalDocument3 pagesWhat Are The Writing of Jose RizalMerylle BejerNo ratings yet

- Course Code: Ge 9: Name: Von Ryan B. Jimenez Section: EDocument7 pagesCourse Code: Ge 9: Name: Von Ryan B. Jimenez Section: ECristelle Estrada-Romuar JurolanNo ratings yet

- BCAS v12n03Document78 pagesBCAS v12n03Len HollowayNo ratings yet

- Indolence of The Filipino PeopleDocument5 pagesIndolence of The Filipino Peoplemiguelcalumba23No ratings yet

- Noli Me TangereDocument2 pagesNoli Me Tangerehat dogNo ratings yet

- Criollismo and Mestizaje in The New WorldDocument66 pagesCriollismo and Mestizaje in The New WorldxinrougeNo ratings yet

- Exercise 3.4.4: Tracing The Family Tree and Uprooting The ProblemDocument3 pagesExercise 3.4.4: Tracing The Family Tree and Uprooting The ProblemSean RiveroNo ratings yet

- SUCESOS Lesson UB - 57138548Document24 pagesSUCESOS Lesson UB - 57138548Shekaina Joy Wansi ManadaoNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 - Customs of TagalogDocument56 pagesTopic 2 - Customs of TagalogDexie DelimaNo ratings yet

- Ascendance of Chinese MestizosDocument5 pagesAscendance of Chinese MestizosMary Antonette TagadiadNo ratings yet

- Rizal's Family Background, Childhood and EducationDocument15 pagesRizal's Family Background, Childhood and EducationJunie JalandoniNo ratings yet

- Rizal 1425Document3 pagesRizal 1425Alex Zhaid0% (1)

- An Insight Paper On Rizal's "The Indolence of The Filipinos"Document2 pagesAn Insight Paper On Rizal's "The Indolence of The Filipinos"grimpilNo ratings yet

- Indolence of The Filipino PeopleDocument5 pagesIndolence of The Filipino PeopleIae Montero100% (1)

- Indolence of The Filipinos HighlightsDocument4 pagesIndolence of The Filipinos HighlightsPaula Mae EspirituNo ratings yet

- MRR Template RIZALDocument2 pagesMRR Template RIZALJV MandigmaNo ratings yet

- The Chinese MestizoDocument25 pagesThe Chinese MestizoCEEJAY LUMBAONo ratings yet

- Afro Indian RelationsDocument10 pagesAfro Indian RelationsJorge_ednNo ratings yet

- GE 9-Group 2 ReportDocument24 pagesGE 9-Group 2 Reportmark encilayNo ratings yet

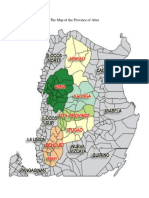

- AbraDocument16 pagesAbraJefferson BeraldeNo ratings yet

- Weightman Anti Sinicism PhilippinesDocument12 pagesWeightman Anti Sinicism PhilippinesJames Cañada GatoNo ratings yet

- Activity: Rosario Manapos Cartagena (Mandaya)Document4 pagesActivity: Rosario Manapos Cartagena (Mandaya)Lowell SantuaNo ratings yet

- The Rise of The Chinese MestizoDocument5 pagesThe Rise of The Chinese MestizoArma DaradalNo ratings yet

- Lrizal Group 1 Annotation (Quote Statements-Questions in The Module)Document22 pagesLrizal Group 1 Annotation (Quote Statements-Questions in The Module)brent fanigNo ratings yet

- Chinese Connection, Agrarian Relations & Friar Lands and Interclergy Conflicts & Cavite MutinyDocument23 pagesChinese Connection, Agrarian Relations & Friar Lands and Interclergy Conflicts & Cavite MutinyJemimah MalicsiNo ratings yet

- 21st BasicDocument4 pages21st BasicSwift36No ratings yet

- The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryDocument15 pagesThe Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryAnjela May HintoloroNo ratings yet

- Chinese and Chinese MestizosDocument16 pagesChinese and Chinese MestizosReycris MasanqueNo ratings yet

- Contextual Analysis of Selected Primary Sources in Philippine HistoryDocument43 pagesContextual Analysis of Selected Primary Sources in Philippine HistoryJomar CatacutanNo ratings yet

- The Katipunan; or, The Rise and Fall of the Filipino CommuneFrom EverandThe Katipunan; or, The Rise and Fall of the Filipino CommuneNo ratings yet

- Takeaways For Weeks 06-07 The Essence of Research in The Study of RizalDocument4 pagesTakeaways For Weeks 06-07 The Essence of Research in The Study of RizalLeiann PongosNo ratings yet

- Pongos, Lei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Solid Upland: Workshop/ActivityDocument1 pagePongos, Lei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Solid Upland: Workshop/ActivityLeiann PongosNo ratings yet

- Lei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Pongos BSA2.1 Managerial Economics MidtermDocument1 pageLei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Pongos BSA2.1 Managerial Economics MidtermLeiann PongosNo ratings yet

- 07 Activity 1 Strategic - ManagementDocument1 page07 Activity 1 Strategic - ManagementLeiann PongosNo ratings yet

- Lei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Pongos BSA2.1 Strategic Management Case Study - Jollibee Corporation'SDocument1 pageLei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Pongos BSA2.1 Strategic Management Case Study - Jollibee Corporation'SLeiann PongosNo ratings yet

- Lei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Pongos BSA2.1 Strategic Management Review 8Document1 pageLei Ann Dendi Lizz C. Pongos BSA2.1 Strategic Management Review 8Leiann PongosNo ratings yet

- 07 Activity 1 Strategic - ManagementDocument1 page07 Activity 1 Strategic - ManagementLeiann PongosNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 - Strategic - ManagementDocument1 pageActivity 1 - Strategic - ManagementLeiann Pongos0% (1)

- Pongos, Lei Ann Dendi Lizz C. BSA2.1 Review 1 Strategic ManagementDocument1 pagePongos, Lei Ann Dendi Lizz C. BSA2.1 Review 1 Strategic ManagementLeiann PongosNo ratings yet

- Insights Mind Maps: India - Israel RelationsDocument2 pagesInsights Mind Maps: India - Israel RelationsVishal SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Philanthropy or The Social ResponsibilityDocument8 pagesThe Role of Philanthropy or The Social ResponsibilityShikha Trehan100% (1)

- Monthly Review: Why Socialism?Document9 pagesMonthly Review: Why Socialism?surbhi prajapatiNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of The Estate of Edward Randolph HixDocument1 pageIn The Matter of The Estate of Edward Randolph HixMaria Louissa Pantua AysonNo ratings yet

- Waked Money Laundering Organization: Panama-Based WAKED MLO AssociatesDocument2 pagesWaked Money Laundering Organization: Panama-Based WAKED MLO AssociatesErika Anruth Martinez LopezNo ratings yet

- The Impact of The University Subculture On Learning English As A Second LanguageDocument20 pagesThe Impact of The University Subculture On Learning English As A Second LanguageGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- DBQDocument11 pagesDBQAlex KimNo ratings yet

- History of Girl ScoutingDocument35 pagesHistory of Girl ScoutingOLGA VICTORIA CEDINO - KALINo ratings yet

- Economic Systems in EthiopiaDocument1 pageEconomic Systems in EthiopiaMeti GudaNo ratings yet

- Approaches in Global Political EconomyDocument13 pagesApproaches in Global Political EconomyClandestain ZeeNo ratings yet

- Singapore International Arbitration Act of 2010Document70 pagesSingapore International Arbitration Act of 2010Julie Ann EnadNo ratings yet

- Procura/imputernicire Power of AttorneyDocument3 pagesProcura/imputernicire Power of AttorneyDan Mihai SlăvoiuNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper Educ 410Document1 pageReaction Paper Educ 410Anamie Dela Cruz ParoNo ratings yet

- SQF2000 CodeDocument16 pagesSQF2000 CodeCătălina BoițeanuNo ratings yet

- Journal of Politics and International Affairs - Spring 2015Document140 pagesJournal of Politics and International Affairs - Spring 2015David NieldNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 12-11-2011Document101 pagesTimes Leader 12-11-2011The Times Leader100% (1)

- Tax 2 Annotations (RAs)Document8 pagesTax 2 Annotations (RAs)Kevin HernandezNo ratings yet

- Moy Ya Lim Yao and Lau Yuen Yeung vs. The Commissioner of Immigration GR No. L-21289Document2 pagesMoy Ya Lim Yao and Lau Yuen Yeung vs. The Commissioner of Immigration GR No. L-21289jury jasonNo ratings yet

- Law Commission of India Report No.257 Custody LawsDocument85 pagesLaw Commission of India Report No.257 Custody LawsLive LawNo ratings yet

- Hacienda Luisita Incorporated Vs Presidential Agrarian Reform CouncilDocument3 pagesHacienda Luisita Incorporated Vs Presidential Agrarian Reform CouncilMark Hiro NakagawaNo ratings yet

- Marihatag, Surigao Del SurDocument2 pagesMarihatag, Surigao Del SurSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Davao Del SurDocument2 pagesDavao Del SurSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- The Constitution of The United States With AmendmentsDocument17 pagesThe Constitution of The United States With AmendmentskgrhoadsNo ratings yet

- Dismas Charitie Y LNC., Ana Gispert, Derek: O. of Fl#. - MI XMIDocument39 pagesDismas Charitie Y LNC., Ana Gispert, Derek: O. of Fl#. - MI XMIcinaripatNo ratings yet

- International Toll-Free NumbersDocument3 pagesInternational Toll-Free NumbersErnesto ZapataNo ratings yet

- SOC 100B 2022 Spring Syllabus 2 RedactedDocument10 pagesSOC 100B 2022 Spring Syllabus 2 RedactedalecNo ratings yet