Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Multiple Sclerosis Neurogenic Bladder 10.1038@nrurol.2016.53

Uploaded by

Putri Rizky AmaliaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Multiple Sclerosis Neurogenic Bladder 10.1038@nrurol.2016.53

Uploaded by

Putri Rizky AmaliaCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEWS

Management of neurogenic bladder

in patients with multiple sclerosis

Véronique Phé1,2, Emmanuel Chartier–Kastler1 and Jalesh N. Panicker2

Abstract | Lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction is common in patients with multiple sclerosis and is

a major negative influence on the quality of life of these patients. The most commonly reported

symptoms are those of the storage phase, of which detrusor overactivity is the most frequently

reported urodynamic abnormality. The clinical evaluation of patients’ LUT symptoms should include

a bladder diary, uroflowmetry followed by measurement of post-void residual urine volume,

urinalysis, ultrasonography, assessment of renal function, quality-of‑life assessments and sometimes

urodynamic investigations and/or cystoscopy. The management of these patients requires a

multidisciplinary approach. Intermittent self-catheterization is the preferred option for management

of incomplete bladder emptying and urinary retention. Antimuscarinics are the first-line treatment

for patients with storage symptoms. If antimuscarinics are ineffective, or poorly tolerated, a range of

other approaches, such as intradetrusor botulinum toxin A injections, tibial nerve stimulation and

sacral neuromodulation are available, with varying levels of evidence in patients with multiple

sclerosis. Surgical procedures should be performed only after careful selection of patients. Stress

urinary incontinence owing to sphincter deficiency remains a therapeutic challenge, and is only

managed surgically if conservative measures have failed. Multiple sclerosis has a progressive course,

therefore, patients’ LUT symptoms require regular, long-term follow‑up monitoring.

Multiple sclerosis is the commonest progressive neuro Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) is a useful tool

logical disorder in young people, with a mean age at to guide the measurement of progression of neurologi

onset of 30 years, and a prevalence of 108 cases per cal disability and includes an assessment of pyramidal,

100,000 people in Europe1. Multiple sclerosis has a cerebellar, brainstem, sensory, bowel, bladder, visual and

progressive course, of which four major subtypes have cerebral functions5. Disease-modifying treatments are

been identified. A relapse–remitting course is most currently available to prevent progression in patients

commonly reported, in 85% of patients with multiple with relapse–remitting multiple sclerosis. Until the past

sclerosis. Nearly 50% of these individuals develop a decade only IFN‑β and glatiramer were available. Now,

progressive course (described as secondary progres newer molecules have become available such as natali

sion) over a median time period of 11 years2. Less com zumab, as well as oral medications such as fingolimod6.

1

Pitié-Salpêtrière Academic monly, patients might have a primary progressive course, These treatments prevent relapses and the possible accu

Hospital, Department of characterized by progressive symptoms from the onset of mulation of neurological disability, however, uncertainty

Urology, Assistance-Publique- disease, or have a progressive, relapsing course. Chronic remains as to whether or not these treatments delay

Hôpitaux, 47–83 boulevard autoimmune T‑cell-mediated inflammation of the progression of non-motor manifestations such as lower

de l’hôpital, 75651 Paris

Cedex 13, France.

central nervous system (CNS), resulting in disruption urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction.

2

Department of Uro- of myelin sheaths, is the pathological hallmark of this LUT symptoms are reported by >80% of patients

Neurology, The National disorder (FIG. 1). Relapse–remitting multiple sclerosis is with multiple sclerosis. Symptoms might occur during

Hospital for Neurology characterized by the appearance of new and active focal the early stages of the neurological disease and some

and Neurosurgery and

inflammatory demyelinating lesions in the white matter, times might be reported at initial presentation7. Clinical

UCL Institute of Neurology,

33 Queen Square, whereas progressive multiple sclerosis is characterized evidence suggests that LUT symptoms most often result

London WC1N 3BG, UK. by diffuse injury of normal-appearing white matter, from spinal cord lesions and, indeed, a correlation exists

Correspondence to V.P. cortical demyelination and axonal loss3,4. between LUT symptoms and the degree of pyramidal

veronique.phe@aphp.fr Owing in part to spinal cord involvement, the inevi symptoms observed in the lower limbs8,9. However,

doi:10.1038/nrurol.2016.53 table progression of multiple sclerosis symptoms leads LUT symptoms might also result from cognitive prob

Published online 31 Mar 2016 to increased disability and a decline in mobility. The lems (memory loss, amotivation, apraxia and language

NATURE REVIEWS | UROLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 1

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Key points Considering the widespread distribution of lesions

throughout the CNS in patients with multiple sclerosis,

• Lower urinary tract (LUT) symptoms are common in patients with multiple sclerosis; the establishing a precise correlation between neurological

exact symptoms vary in type and severity, and can evolve with progression of the disease lesions and LUT dysfunction is often difficult; how

• The management of LUT dysfunction in these patients requires a consensual approach, ever, the prevalence of LUT dysfunction increases with

with cooperation between different medical professionals, and should take into longer disease duration and greater physical disability22.

consideration possible progression of the disease Furthermore, the presence of LUT symptoms might

• Intermittent self-catheterization is essential for the management of patients with be overlooked in the clinical management of patients

voiding symptoms, but might also have a role in management of those with with multiple sclerosis. Indeed, results of a survey con

storage symptoms

ducted by the North American Research Committee

• Intradetrusor botulinum toxin A injections are a highly effective and minimally invasive On Multiple Sclerosis, published in 2010, revealed that

treatment of storage dysfunctions

only 43% of patients with the disease with moderate to

• Surgical options include augmentation cystoplasty, cutaneous continent diversion and severe overactive bladder symptoms had their symptoms

ileal conduit surgery, and should be performed only after careful selection of patients

evaluated by a urologist22.

• Multiple sclerosis has a progressive course and, therefore, patients with multiple

sclerosis who also have LUT symptoms require regular long-term follow‑up monitoring

Urodynamic presentation

Urodynamic investigations enable precise evaluation

of the functional pathophysiology of patients’ specific

dysfunction), additional localized causes (bladder out LUT dysfunction and of the risk factors for urinary

let obstruction, urinary tract infection or stress incon tract damage in patients with multiple sclerosis, thus

tinence), functional incontinence (reduced mobility helping clinicians to plan the optimal management

or general debilitation) or medications (such as opioid of LUT symptoms. Detrusor overactivity is the most

analgesics or tricyclic antidepressants). LUT symptoms, frequently reported urodynamic abnormality, with a

like cognitive symptoms, also progressively worsen, and prevalence of 34–91%8,14–18,23. Detrusor underactivity

become more difficult to manage with increasing dis is reported in ≤37%, and low bladder compliance in

ability. Furthermore, LUT symptoms negatively influ 2–10% of patients with multiple sclerosis14,18,23. Detrusor

ence patients’ quality of life. Data from several studies activity can also be normal in 3–34% of patients with

have shown that, in terms of patients’ overall quality of multiple sclerosis reporting LUT symptoms14,18,23. The

life, urinary incontinence is considered to be one of the reported prevalence of detrusor–sphincter dyssyner

worst aspects of living with this disease10,11. In a self- gia (DSD) in these patients ranges from 5–60%14–18,23

selected group of patients with multiple sclerosis who and this variation probably reflects the patient group

responded to a questionnaire, 70% of patients consid studied and/or technical difficulties in detecting abnor

ered the disruptive effect of LUT symptoms on their mal detrusor–sphincter contraction. With a median

life as ‘high’ or ‘moderate’ (REF. 11). Several therapeutic prevalence of 35%, DSD becomes more common if

options are currently available to treat LUT symptoms in patients’ symptoms are monitored over a longer period

patients with multiple sclerosis. The aim of this Review of time24. Urodynamic abnormalities also often coexist:

is to describe the diagnosis and management of LUT DSD can be combined with either detrusor overactiv

dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. ity in 43–80% of patients or with detrusor underactivity

in 5–9%, resulting in incomplete bladder emptying24.

Presentation of LUT dysfunction However, urodynamic abnormalities can also be identi

Clinical presentation fied in patients who are asymptomatic15. Urodynamic

Over 80% of patients with multiple sclerosis report the abnormalities can also change with time in any given

incidence of LUT symptoms. This figure can vary, how patient with the evolution of the disease. Following a

ever, according to the severity of the neurological dis urodynamic study of 22 patients, with a mean follow‑up

ability of patients in the study cohort12,13. LUT symptoms duration of 42 months, investigators reported that 12

generally appear after a mean of 6 years of evolution of of these 22 patients, whose symptoms were assessed

the neurological disease13 and might be reported as a using repeated cystomanometric tests, had changes

presenting complaint in 10% of patients. Patients with in their bladder capacity, contractility, pressure or

multiple sclerosis can present with a wide range of LUT detrusor compliance during the follow‑up period25.

symptoms. Of these, symptoms of the storage phase Only those with DSD, which was observed in 13

(overactive bladder symptoms) are the most frequently of the patients, had stable urological symptoms during

reported. Indeed, increased urinary urgency is observed the follow‑up period25.

in 38–99% of patients with multiple sclerosis, increased No evidence exists that a patient’s age or type of

urinary frequency in 26–82% and urge incontinence multiple sclerosis (remittent or progressive) has any

in 27–66%8,14–18. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is influence on their urodynamic presentation. However,

also frequently reported with a prevalence of 56%, and a patient’s gender might independently influence uro

patients often report mixed urinary incontinence19. By dynamic presentation, with a significant increase in

contrast, symptoms of the voiding phase are less fre the maximum amplitude of uninhibited detrusor con

quent, with a prevalence of 6–49%8,17,18. Symptoms of tractions, of the detrusor leak-point pressure (defined

both the storage and voiding phases can coexist in 50% as the lowest detrusor pressure at which urine leakage

of patients20,21. occurs in the absence of either a detrusor contraction

2 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrurol

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

a Inflammatory neuronal damage b Non-inflammatory neuronal damage

Oligodendrocyte

Microglia

Pro-inflammatory and

cytotoxic molecules Neuronal connectivity

Macrophage

Activated

microglia

Damage

CD4+ B cell Retrograde Anterograde

CD8+ T cell degeneration Wallerian

T cell degeneration

Degeneration

Pycnotic nuclei

Anterograde Wallerian Neuronal dying back Retrograde Anterograde

degeneration degeneration Wallerian

degeneration

Figure 1 | Mechanisms of neuronal injury and degeneration in patients with multiple sclerosis. a | Proinflammatory

and cytotoxic molecules released by inflammatory cells within subarachnoid or intracortical immune Nature Reviews

infiltrates, | Urology

as well as

cell contact-dependent mechanisms of T-cell mediated damage, might lead to microglia and/or macrophage activation

and oligodendrocyte injury. This process can directly or indirectly lead to death of the neuronal cell body and nuclei

(lower panel). Such cell death leads to morphological alterations, such as the characteristic pycnotic nuclei, shrinkage of

dendrites and axonal degeneration in the cerebral cortex. This could in turn lead to dysfunction of the downstream

neuronal network via anterograde trans-synaptic (Wallerian) degeneration. b | Undisturbed neuronal connectivity, and its

related functions, could be impaired by retrograde degeneration propagating backwards in cortical neurons whose axons

have been damaged in white matter lesions or along white matter tracts such as the corticospinal tract. This white matter

tract damage can lead to microglial activation and retrograde neuronal cell death. Reproduced with permission obtained

from Nature Publishing Group © Calabrese, M. et al. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 147–158 (2015).

or increased abdominal pressure) and of the maximum overactivity and DSD (FIG. 2). However, considering the

detrusor pressure in men compared with women14. The multitude of lesions that characterize this condition,

prevalence of DSD increases with the duration of mul establishing the relative contributions of individual

tiple sclerosis. Thus, DSD is present in 13% of patients lesions to LUT dysfunction is often not possible. In gen

after 48 months of evolution of multiple sclerosis, in eral, lesions that are more caudally placed have a greater

15% of patients between 48 months and 109 months, effect on LUT dysfunction and LUT dysfunction arises

and in 48% of patients 109 months after diagnosis20. most often following spinal cord involvement. In a few

The correlation between detrusor overactivity and a studies, investigators have attempted to evaluate the

higher EDSS score or pyramidal damage seems prob association between the site of the lesion and the spe

able14,26 and a correlation between DSD and pyramidal cific LUT dysfunction. Indeed, the presence of DSD has

damage or the degree of disability has also been sug been reported to be indicative of cervical spinal cord

gested8,14,20. However, no correlation between detrusor lesions, and detrusor hyporeflexia to be indicative of a

underactivity and neurological symptoms has, thus far, pontine lesion23.

been reported15.

Complications of LUT dysfunction

Pathophysiology of LUT dysfunction Urological complications are less frequently reported

In the pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis, lesions in patients with multiple sclerosis compared with those

of the CNS result in a characteristic pattern of LUT with other neurological disorders, such as traumatic

dysfunction according to the specific location of these spinal cord injury or spina bifida, but they are certainly

lesions. Whereas subcortical white-matter lesions not rare14,20. Potential urological complications include

result in detrus or overactivity, lesions of the spinal pyelonephritis (9% of patients), upper tract dilata

cord result in the combined occurrence of detrusor tion (8%), bladder stones (5%), kidney stones (5%),

NATURE REVIEWS | UROLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 3

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

vesicoureteral reflux (5%), renal failure (2–3%) and Assessment of quality of life

bladder cancer (0.29%), although this risk increases (to Many questionnaires are available to assess

5.7%) in regular catheter users16,27–30. Hence, urological LUT-symptom-related quality of life. However only

complications are probably the most common cause Qualiveen® (MAPI research trust, Lyon, France)34 is

of hospitalization in patients with multiple sclerosis14. validated for evaluation of the quality of life of patients

In an epidemiological study, the risk of renal failure in with neurological disease and is recommended by the

patients with multiple sclerosis was found to be equiv European Association of Urology (EAU)35. This ques

alent to the risk reported in the general population20,31. tionnaire comprises 30 items and covers bother (nine

Identified risk factors for complications included detru items), constraints (eight items), fears (eight items) and

sor overactivity, elevated intravesical pressure, the pres feelings (five items). Each item is scored from 0–4. Each

ence of an indwelling catheter and the duration of the of the four scales are scored from 0–100, with lower

neurological disease20,32. scores indicating a better quality of life (meaning fewer

limitations, fears, constraints or negative feelings) and

Clinical investigations higher scores indicating a worse quality of life. The

The evaluation of patients with multiple sclerosis report Qualiveen® questionnaire is currently translated into

ing LUT symptoms should include use of a bladder diary, six different languages.

uroflowmetry followed by measurement of post-void

residual volumes, urinalysis, ultrasonography, assess Urinalysis

ment of renal function and sometimes a urodynamic Findings from urinalysis help to provide evidence of

study and /or cystoscopy. An assessment of a patient’s any urinary tract infections and urinalysis should be

quality of life is an integral part of the evaluation20. performed in all patients during their initial evaluation

or, subsequently, when reporting the occurrence of new

Bladder diary symptoms. Negative urinalysis findings (for example,

The International Continence Society (ICS) recom revealing a lack of leukocyte esterases and/or nitrites)

mends the use of a bladder diary in the clinical assess are useful in excluding the possibility that symptoms are

ment of patients with LUT symptoms. The bladder caused by infections as this test has a high negative pre

diary is an extension of history taking and provides a dictive value (>98%). However, the positive predictive

prospective, real-time assessment of LUT symptoms, value is low (around 50%)36. Thus, when an infection

fluid intake and baseline LUT symptoms before man is suspected, midstream or catheter urine specimens

agement, and also helps to evaluate the outcomes of any should be sent for microbiological culture. For patients

treatment33 (FIG. 3). who perform intermittent self-catheterization (ISC) or

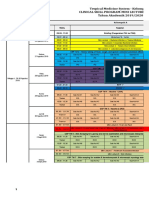

Suprapontine lesion Over-

• History: predominantly storage symptoms active

• Ultrasound: insignificant PVR urine volume

• Urodynamics: detrusor overactivity

Normo-active

Spinal (infrapontine-suprasacral) lesion Over-

• History: both storage and voiding symptoms active

• Ultrasound: PVR urine volume usually raised

• Urodynamics: detrusor overactivity, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia

Overactive

Under- Under-

Sacral/infrasacral lesion active active

• History: predominantly voiding symptoms

• Ultrasound: PVR urine volume raised

• Urodynamics: hypocontractile or acontractile detrusor

Normo-active Underactive

Figure 2 | Patterns of lower urinary tract dysfunction following neurological disease. The pattern of lower urinary

Nature Reviews | Urology

tract dysfunction following neurological disease is determined by the site and nature of the lesion. The blue box denotes

the region above the pons and that in green denotes the sacral cord and infrasacral region. Figures on the right show the

expected dysfunctional states of the detrusor–sphincter system. PVR, post-void residual. Reproduced with permission

obtained from Elsevier © Panicker, J. et al. Lancet Neurol. 14, 720–732 (2015).

4 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrurol

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

The management pf patients with multiple sclerosis and LUT symptoms treatment or if the patient has had recurrent urinary

tract infections, measurement of the post-void residual

Assessment

volume should be repeated.

• History • Urinalysis/culture

• General assessment, quality • Urinary tract imaging,

of life, expectations from measures of renal function Urodynamics

treatment • Measuring post-void Urodynamic techniques, including uroflowmetry and

• Bladder diary residual volume

• Physical examination • Urodynamics filling cystometry, with or without additional synchro

nous fluoroscopic screening (videourodynamics), are

all useful methods of examining LUT function, ena

Storage symptoms bling evaluations of the pressure–volume relationship

Detrusor overactivity during non-physiological filling of the bladder and

during voiding.

The need to perform a urodynamic investigation in all

Disability

Increased post-void Normal post-void

residual volume residual volume patients with multiple sclerosis during initial assessment

is currently under debate, as the risk of damage to the

upper urinary tract is considered to be lower in patients

Learn ISC Treatment options with multiple sclerosis compared with that of those with

other neurological disorders, such as spinal-cord injury

or spina bifida20,31,40,41. Guidelines published by The UK

Behavioural therapies National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

and a Turkish consensus statement provide guidance on

the management of patients with urinary incontinence

Antimuscarinics owing to neurological disease; both guidelines recom

mend not to offer urodynamic investigations (such as fill

Tibial nerve stimulation Intradetrusor

ing cystometry and/or pressure–flow studies) routinely

sacral neuromodulation? BoNT-A injections to patients with neurological disease who are known to

have a low risk of renal complications (for example, most

patients with multiple sclerosis)40,42. By contrast, the

Yes International Francophone Neuro-Urological Expert

ISC possible? Study Group (GENULF) recommends using urodynam

No ics in the initial diagnosis of patients20. The inclusion of

urodynamics in the routine assessment of patients with

Augmentation Incontinent urinary diversion– Indwelling urethral/ multiple sclerosis is, therefore, determined by the avail

cystoplasty option in selected patients suprapubic catheter

able local guidance; however, urodynamic investigations

Figure 3 | Algorithm for the management of storage symptoms in patients with are generally recommended in patients with risk factors

Natureof

multiple sclerosis. Maintaining quality of life, including preservation Reviews | Urology

renal function predisposing to upper urinary tract damage such as in

is the primary aim of management of these symptoms. At initial presentation, the most those with concomitant SUI, in those whose symptoms

conservative approaches should be considered the primary treatments of storage have failed to respond to first-line treatment or if surgical

symptoms; although, as patients’ disease progresses, more invasive management treatment is being considered9,43.

approaches might be required. BoNT-A, botulinum neurotoxin A; ISC, intermittent self

catherization; LUT, lower urinary tract. Assessment of renal function

Creatinine clearance, calculated based upon analysis of a

24‑hour urine sample, is a more accurate method of esti

have an indwelling catheter, findings of microbiologi mating kidney function than serum creatinine level or

cal urinalysis will almost invariably be positive owing the estimated glomerular filtration rate44.

to chronic bacteriuria. Thus, periodically sending urine

samples for culture should be discouraged in the absence Other investigations

of fresh neurological or urological symptoms37–39. Other investigations, such as cystoscopy or retrograde

ureterocystography might be required and the need

Ultrasonography for these should be assessed on a case‑by‑case basis.

Findings of renal ultrasonography in patients with Cystoscopy might be indicated in individuals with recur

multiple sclerosis can be entirely normal but can also rent urinary tract infections to investigate the presence of

sometimes reveal the presence of hydronephrosis and/or stones or diverticulae, or if risk factors for bladder c ancer

stones, both of which require a specific management are present20. Retrograde cystography is performed to

plan. Measurements of the post-void residual volume assess any vesicoureteral reflux, although, this might also

form part of the initial assessment, and this is measured be identified using videourodynamics45.

either using ultrasonography, or alternatively using a

single in–out catheterization, followed by measurement Management

of the subsequent volume of urine. Furthermore, if the The management of LUT symptoms in patients

clinician has reason to suspect a patient has developed with multiple sclerosis requires a multidisciplinary

incomplete bladder emptying owing to the effects of a approach involving the input of urologists, neurologists,

NATURE REVIEWS | UROLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 5

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

rehabilitation physicians, continence advisers and the were randomly allocated to one of two groups. Group

various stakeholder groups that represent patients35. one, in which patients received pelvic floor muscle train

In patients with multiple sclerosis, the overall, long-term ing, electromyography biofeedback and placebo neuro

aims of management are to protect the upper urinary muscular electrical stimulation (n = 37), and group two,

tract, to achieve continence and to improve the patient’s in which patients received pelvic floor muscle training,

overall quality of life. The management strategy has to electromyography biofeedback and active neuromuscular

take both the neurological disability and the patient’s electrical stimulation (n = 37). After 9 weeks of treatment,

living environment into consideration. Furthermore, the mean number of incontinence episodes observed in

considerations should be given to urinary and bowel group two was significantly greater than that observed

functions together if both systems are affected, as both in group one (by 85% versus 47% of baseline levels,

symptoms and treatments of one system might also influ respectively; P = 0.0028)49. However, despite these encour

ence the other43. In patients presenting with both storage aging results, concomitant treatment with antimuscarinics

and voiding LUT symptoms, the management strategy was maintained in the majority of studies in this area54.

should combine the treatments available for storage Consequently the exact effects of isolated use of physical

symptoms and the treatments for voiding symptoms. treatments cannot be accurately assessed.

Management of storage symptoms Medical treatment

General measures and physical treatments Antimuscarinics

A fluid intake of 1.5–2 l per day is recommended in the Antimuscarinics and/or intermittent self catheterization

general population and, although not specifically recom (ISC) are the cornerstone of LUT symptom management

mended, this level of intake should also apply to patients in patients with early-stage multiple sclerosis55. The use

with multiple sclerosis. Furthermore a reduction in caf of antimuscarinics results in a decreased sensation of uri

feine intake below 100 mg per day has been shown to nary urgency, an improvement in continence, an increase

reduce symptoms of the storage phase46. in bladder capacity, a significant reduction of maximum

Physical therapy can be effective for the treatment of detrusor pressure and a significant improvement in qual

LUT symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis with ity of life of patients with a variety of neurological dis

mild disability 47–51. In our own clinical experience of such eases56–58. In patients with multiple sclerosis, the evidence

an approach, bladder retraining involves the patient vol base supporting the clinical use of antimuscarinics is

untarily ‘holding on’, or refraining from voiding with a limited. Not all currently available antimuscarinics have

fairly full bladder for increasingly longer periods of time, been systematically investigated in patients with multi

often as part of an incremental programme supervised ple sclerosis and their use is often based upon inferences

by specialist continence advisers or physiotherapists. Of of efficacy from data from other patient groups58. The

course, these interventions can only be expected to be efficacy, tolerability and safety of anticholinergic drugs

effective in patients with intact neural control of their pel among patients with multiple sclerosis was assessed in

vic floor muscles; therefore, an assessment of a patient’s a Cochrane review published in 2009 (REF. 59). However,

control of their pelvic floor muscles should be made this review included data from only three single-centre

before initiating treatment. Such interventions are often randomized crossover trials that were either placebo-

difficult to initiate in patients with cognitive impairments. controlled or designed to compare the effects of two

Regular pelvic floor exercises can enhance the inhibitory or more treatments57,60,62. In the Cochrane review59, the

effect of pelvic floor contractions on the detrusor52. authors did not find sufficient evidence to prove any sig

A prospective trial was conducted to investigate the nificant benefit of antimuscarinics in patients with mul

effects of pelvic floor rehabilitation as a treatment of tiple sclerosis. The authors also noted a high incidence of

detrusor overactivity in 30 female patients with multiple adverse effects (such as dry mouth or constipation) with

sclerosis53. In 25 of these 30 patients, the strength of the more than one in five trial participants having to with

pelvic floor was significantly improved after one month draw from antimuscarinic treatment59. Findings of sys

of regular exercises (P <0.001). A significant increase in tematic reviews do not support the superiority of any one

mean functional bladder capacity, as read from patients’ drug over another. However, the most clinically relevant

voiding charts, was also observed (from 173.8 +/– 53.9 differences between antimuscarinics are in the adverse

to 208.5 +/– 57.6 cm3; P = 0.005). Furthermore, the mean event profile. For example, tolterodine, when used at self-

urinary frequency decreased significantly (from 12.7 +/– selected doses, is comparable with oxybutynin in terms

3.6 to 9.1 +/– 2.6 voids per day; P <0.01) as did the mean of increasing patients’ bladder capacities and improving

number of daily episodes of incontinence (from 2.8 +/– continence, but with less dry mouth62. The intravesical

1.3 to 1.5 +/– 1.5 episodes per day; P <0.01)49. Moreover, administration of atropine is an interesting approach that

combining active neuromuscular electrical stimulation has been reported to be as effective as oral oxybutinin,

with pelvic floor muscle training and electromyography with fewer adverse effects57. However, the limited avail

(EMG) biofeedback can result in a substantial reduction ability of atropine and the necessity to visit the clinic for

in the severity of LUT symptoms53. each instillation is a major inconvenience, which restricts

Further evidence for the combination of pelvic floor the use of this approach.

exercises with neuromuscular electrical stimulation is pro Cognitive impairment is reported in patients with

vided by a randomized controlled trial: 74 patients with multiple sclerosis, especially as the disease advances,

multiple sclerosis who presented with LUT dysfunction and the choice of antimuscarinic should, therefore, be

6 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrurol

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

guided by the potential risk of adverse effects on the trial with a cohort of 647 patients with multiple scler

CNS. Medications such as trospium chloride are, rela os is, oral administration of a cannabis extract or

tive to oxybutynin, tolterodine and solifenacin, less likely Δ9‑tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9‑THC) reduced the fre

to cross the blood–brain barrier and might be a medica quency of urge incontinence episodes (by 38%, 33% and

tion to consider in patients with advanced-stage multiple 18%, respectively; P = 0.05 and 0.039 for comparisons of

sclerosis. Darifenacin, a selective antagonist of the M3 cannabis extract or Δ9‑THC with placebo, respectively)

receptor, which is not known to be involved in cogni and pad weight (mean reduction of 44.7 ml, 43.2 ml and

tion, provides an alternative to trospium41. However, 43.9 ml for cannabis extract, Δ9‑THC or a combination

studies supporting the use of darifenacin specifically of treatments, respectively, versus a mean increase of

in patients with multiple sclerosis are currently lacking. 8.3 ml for placebo; combined mean difference versus

Combinations of regular doses of two different anti placebo of 52.1 ml, 95% CI 13.4–90.9 ml; P = 0.001)74.

muscarinics have been shown to be effective and well In a small open-label trial including 21 patients with

tolerated in a few patients63. advanced-stage multiple sclerosis, the safety, tolerability,

In conclusion, antimuscarinics remain widely pre dose range and efficacy of two whole-plant extracts of

scribed agents despite the availability of only limited cannabis sativa was evaluated. Patients received extracts

evidence of their efficacy or effectiveness in patients containing Δ9‑THC and cannabidiol (CBD; 2.5 mg of

with multiple sclerosis. Use of these agents can improve each per spray) for 8 weeks followed by Δ9‑THC only

symptoms of the storage phase and patients’ quality of (2.5 mg THC per spray) for a further 8 weeks, and then

life. However, patients must be informed of the poten entered into a long-term extension phase. Urinary

tial long-term adverse effects, including the risk of an urgency, the number and volume of incontinence epi

increased post-void residual volume, which then might sodes, urinary frequency and the number of episodes

require ISC. of nocturia all decreased significantly following treat

ment (P <0.05). However, daily total volume voided,

Desmopressin catheterized, and urinary incontinence pad weights

Treatment with the synthetic antidiuretic hormone des also decreased significantly in patients who received

mopressin, used orally or intranasally at different doses both extracts75.

(from 10–100 μg), has been shown to reduce night time Data from a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-

urinary frequency in patients with multiple sclerosis64–71. controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of sublingual

Some of these data are from randomized-controlled Sativex® (GW pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, UK),

trials, and some from other studies. These investiga which is an endocannabinoid modulator consisting of

tions64–71 generally included only small numbers of THC and cannabidiol, in a 1:1 ratio, in patients with

patients with multiple sclerosis and had short (<6‑week) advanced-stage multiple sclerosis demonstrated some

durations of both treatment and follow‑up monitoring. improvements in the frequency of episodes of urinary

If taken during the day, similar doses of desmopressin incontinence, daytime urinary frequency and nocturia76.

to those used at night can also provide relief from LUT However, no significant differences in the frequency of

symptoms for up to 6 hours without rebound nocturia72. episodes of urinary incontinence was observed between

Moreover, the use of desmopressin is associated with res patients who received Sativex® and those who received

toration of sleep patterns and substantial improvements placebo after 8 weeks of treatment, despite this being the

in LUT symptoms, as determined using the International primary endpoint of the study76. A license was granted in

Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire– 2010 for the use of Sativex® to treat spasticity in patients

Overactive Bladder questionnaire72. However, hypo with multiple sclerosis in the UK; although, this license

natraemia is a serious adverse effect of desmopressin, does not apply to the treatment of LUT symptoms.

and serum sodium levels should be checked before the

drug is administered to establish a baseline level, and Intravesical treatments

at day 3 and day 7 after commencing daily administra Onabotulinum toxin A (BoNT‑A), which is commer

tion72. Thus, desmopressin is not recommended for use cially available as BOTOX® (Allergan, Irvine, California,

more than once daily, and should be used with caution USA) has been licensed since 2012 in several countries

in elderly patients (defined as those >65 years of age). for use in patients with treatment-refractory neurogenic

Other adverse effects of desmopressin include headaches detrusor overactivity owing to multiple sclerosis or spi

(3.2–18.7%), nausea (3.2–10.5%), fluid retention (36.8%) nal cord injury. BoNT‑A is the only type of botulinum

and rhinitis and/or epistaxis (3.2–10.5%)64–71. toxin to be evaluated for the management of any LUT

dysfunction in large, multicentre, randomized controlled

Cannabinoids trials77–80. However, the use of abobotulinum toxin A,

Some evidence exists supporting the use of cannabinoids which is commercially available as Dysport® (Ipsen,

in the management of LUT symptoms in patients with Paris, France) as a treatment of neurogenic detrusor

multiple sclerosis. The rationale for cannabinoid use in overactivity but not other forms of LUT dysfunction, is

the control of LUT symptoms stems from the established also supported by a high level of evidence81.

expression of cannabinoid receptors of both subtypes BoNT‑A has several putative mechanisms of action;

(CB1 and CB2) in the urothelium and afferent nerves in addition to inhibiting the release of vesicular neuro

of the human bladder, similar to those of several other transmitters from parasympathetic nerve terminals

experimental animals73. In a large, placebo-controlled of the detrusor smooth muscle, this toxin is also

NATURE REVIEWS | UROLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 7

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

likely to inhibit the release of transmitters involved in with end-stage multiple sclerosis, that intradetrusor

afferent signalling pathways in the bladder mucosa82. injections of BoNT‑A might provide some benefit to

Intradetrusor injections of BoNT‑A are highly effective patients with an indwelling urethral catheter who report

in reducing the incidence of urinary incontinence, in urine leakage owing to catheter bypassing87.

improving patients’ urodynamic parameters and, there

fore, their quality of life77–79,83. Two doses of BoNT‑A, Neuromodulation

200 units versus 300 units, have been tested in two Stimulation of the tibial nerve or sacral nerve root S3

double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trials has proven to be successful in managing overactive

with cohorts of patients with neurogenic detrusor over bladder symptoms. The exact mechanisms of action of

activity owing to either multiple sclerosis or spinal cord this approach remain uncertain but are thought to be

injury78,79. Data from both studies did not reveal any a result of modulation of spinal pelvic reflexes through

significant differences in efficacy between doses; how activation of inhibitory interneurons88.

ever, the need to initiate ISC after injections was higher

in those receiving 300‑unit injections than in those Tibial nerve stimulation. Tibial nerve stimulation can

receiving 200‑unit injections or placebo (12%, 30% and be administered either using a needle to deliver electri

42%79 and 10%, 35% and 42%79 of patients not already cal stimulation (the percutaneous approach) or using

using ISC required ISC after receiving placebo, 200‑unit an electrode patch (the transcutaneous approach).

or 300‑unit injections, respectively). The effects of The transcutaneous method has the advantage that it

BoNT‑A injections usually last for 6–9 months, there can be easily used at home, either by the patient or by

fore, repeated injections are often necessary. All patients their carer, in comparison to the percutaneous method,

with multiple sclerosis should have been taught, or which requires the insertion of a needle close to the tibial

agreed to learn to do ISC before being treated with nerve by a health-care professional. Percutaneous tib

BoNT‑A injections as 88% of patients need to perform ial nerve stimulation has been shown to be effective in

de novo ISC83. However, the need for ISC did not affect managing storage symptoms and improving urodynamic

quality of life outcomes83. parameters in patients with multiple sclerosis89–91. Initial

Mehnert et al.84 investigated the effects of 100‑unit percutaneous stimulation is usually delivered during

injections of BoNT‑A in 12 patients with multiple scler 30‑min, weekly sessions, over a period of 10–12 weeks,

osis and overactive bladder symptoms. Follow‑up visits and generally followed in responders by a period of

were planned 6–7 and 12–14 weeks after injections. maintenance therapy, of which the optimal characteris

Investigators found that 6–7 weeks following the injec tics are poorly defined. This therapy is safe, the patients’

tion, maximum bladder capacity increased significantly reported subjective and objective cure rates are between

(P = 0.034), and maximum detrusor pressure (P = 0.004), 60–80%, patients’ treatment satisfaction is generally high

daytime urinary frequency (P = 0.004), urinary urgency (70%) and their overall quality of life is usually improved

(P = 0.008) and pad use (P = 0.011) all decreased sig substantially89,91–94. Data from a study of 19 patients with

nificantly. Furthermore, daytime urinary frequency multiple sclerosis who received weekly, 30‑min percu

(P = 0.002), night time urinary frequency (P = 0.005), taneous stimulation of the tibial nerve for 12 weeks

urinary urgency (P = 0.013) and pad use (P = 0.02) all revealed a significant improvement in urodynamic

decreased significantly 12–14 weeks following injec parameters, including maximum cystomanometric

tions. Post-void residual volume significantly increased capacity (increased from 199.7 to 266.8 ml; P < 0.001),

in these patients following 100‑unit BoNT‑A injections, maximum detrusor pressure at maximum cystoman

and reached 222 ml initially but decreased progressively ometric capacity (decrease from 48.8 to 35.8 cm H2O;

for 12 weeks post-treatment; overall, three patients P = 0.001), maximum flow rate (increased from 11.6

needed to perform de novo ISC84. Further studies, with to 13.2 ml; P = 0.003) and post-void residual v olume

larger populations and longer follow‑up durations are (decreased from 82.9 to 48 ml; P = 0.006)95.

required to investigate the benefits of a lower dose of The efficacy of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimula

BoNT‑A in patients with multiple sclerosis who are not tion has been proven in a multicentre study of a cohort

willing or able to self-catheterize. An alternative option of 70 patients with multiple sclerosis and symptoms of

for patients who cannot reach the urethra to perform overactive bladder96. All patients received transcutan

ISC is to control LUT symptoms using intradetrusor eous tibial nerve stimulation for 20 minutes per day, for

BoNT‑A injections and create a continent urinary diver a period of 3 months. Clinical improvement in symp

sion using a catheterizable channel (Mitrofanoff, Monti toms was observed in 82.6% and 83.3% of the patients

or Casale’s principles)85. In our own clinical experience, on day 30 and day 90, respectively, with significant

BoNT‑A injections do have to be repeated following sur improvements in urinary urgency, frequency, patients’

gery, although generally, the patient can still perform ISC self-reported symptoms, continence and quality of life

using this continent stoma. observed between day 0 and day 90 of the study (P <0.05

Furthermore, the use of BoNT‑A injections has also for all changes)96. The initial acute cystometric response

been shown to decrease the incidence of symptomatic (defined as a >30% increase in cystometric capacity

urinary tract infections. This effect seems to be related and/or reflex volume) to the first session of transcu

to improvement in urodynamic parameters, reflecting taneous stimulation was positive in 51.2% of patients,

improved reservoir capacity at low bladder pressures86. without any notable correlations with longer-term clini

Finally, evidence exists, from a series of three patients cal effectiveness of the treatments96. Further studies are

8 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrurol

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

required in order to assess the long-term effects of per 62 patients with a neurological condition (among them

cutaneous neuromodulation and to better understand 13 had multiple sclerosis) receiving sacral neuromodu

the need for ‘top up’ to maintain these effects. lation therapy, the reported revision and explantation

The safety of tibial nerve stimulation is particularly rates were 10.4% and 12.5% respectively. Complications

useful to patients who are disabled, who might be more included wound seroma (0.8%), wound infection (4.1%),

susceptible to the deleterious adverse effects of anti back pain (0.8%), leg pain (1.2%), implantable perma

muscarinics than those with a lower level of disability. nent generator site pain (8.2%), a sensation of shock

In our own clinical experience, in such populations, the upon stimulation (0.8%), lead breakage (2.5%), lead

use of tibial nerve stimulation as the first-line treatment migration (0.8%) and device malfunction (3.3%)101.

can be considered appropriate; although, this sugges Published data are available from other studies in this

tion is not supported by any published evidence, thus area, however, these studies included only small num

far. The advantage, to the clinicians, of the percutan bers of patients with multiple sclerosis and are highly

eous approach over the transcutaneous method is that heterogeneous102–106: most of the series were retrospective

patients’ symptoms can be monitored on a weekly basis and data from patients with multiple sclerosis were gen

by the health-care team. However, patients might con erally not analysed separately from data from patients

sider a weekly visit to be a constraint, especially if they with other neurological conditions. Currently, no data

are disabled. Use of the transcutaneous method has from randomized controlled trials are available in this

the advantage that patients can benefit from receiv area, and the types of patients who are most suitable for

ing the treatment at home, but without the possibility sacral neuromodulation is also largely unknown.

of checking if the stimulation they are receiving is opti

mally conducted. By contrast, the lack of any proven Surgery

ameliorative effects on increased detrusor pressures Surgical treatments of LUT dysfunction in patients with

might be a limitation of the percutaneous approach in multiple sclerosis are appropriate in certain situations:

patients with severe neurogenic detrusor overactivity when conservative therapies have failed; when ISC

and high detrusor pressures, which increase the risk of through the urethra is not possible; or in patients with

damage to the upper urinary tract. serious complications such as sepsis, urethral or perineal

fistulae, renal failure or severe urinary incontinence.

Sacral neuromodulation. Sacral nerve stimulation is a

minimally invasive treatment that can be used to treat Augmentation cystoplasty. In highly-motivated patients

patients with treatment-refractory LUT symptoms where ISC can be achieved in the long term, but whose

owing to a range of different underlying neurological LUT symptoms are refractory to more-conservative

diseases97. Similar to other forms of neuromodulation, treatments, augmentation cystoplasty is recommended.

the exact underlying neurophysiological mechanisms of The goal of an augmentation cystoplasty procedure,

action are complex and currently not fully understood. which involves surgically enlarging the bladder, is to

Neuromodulation might exert its effect through acti restore a low-pressure and compliant reservoir and, thus,

vation of afferent pathways that modulate the activity achieve urinary continence. This procedure is often per

of other neural pathways within the spinal cord and formed using a segment of detubularized ileon to aug

higher centres98. Results of a study, published in 2000, ment the urinary bladder. Zachoval et al.107 reported the

show that urodynamic parameters improve from base outcomes of augmentation ileocystoplasty performed in

line to 6 months post-implantation, including maximum nine patients with multiple sclerosis, of whom eight had

bladder capacity (from 244 ml to 377 ml), volume at first detrusor hyperreflexia that was refractory to conserva

uninhibited contraction (from 214 ml to 340 ml) and the tive treatment and one had renal insufficiency. With

average number of voids per day (from 16.1 voids to 8.2 a follow‑up duration of 6–19 months, investigators

voids)97. The findings of a meta-analysis published in recorded an increase in the maximum mean detrusor

2010 indicate that sacral neuromodulation might be capacity from 105 to 797 ml and a decrease in the maxi

effective (in terms of reduced incontinence and fewer mum detrusor pressure from 53 cm H2O to 30 cm H2O.

voids per day) and safe in patients with neurogenic LUT A substantial improvement in LUT symptoms was

dysfunctions99. Elsewhere, in a retrospective case series observed in all patients and the quality-of‑life score, as

of 33 patients with neurogenic LUT dysfunctions, 31 assessed using a questionnaire with a 0–6 scale (0 indi

reported satisfaction with their treatment100. However, cating excellent quality of life, six indicating unbear

the course of the underlying neurological disorder has able), improved from a mean of five to 0.7 (REF. 107).

been shown to adversely influence the ability to derive Importantly, the patient who had renal insufficiency

long-term benefits from sacral neuromodulation101,102. had a decrease in serum creatinine from 286 μmol/l to

As a result, some authors have proposed that sacral 150 μmol/l, suggesting that this surgery had a renopro

neuromodulation should be used in patients with mul tective effect in this patient108. Elsewhere, in more var

tiple sclerosis of a relapse–remitting course, who have ied but larger patient cohorts, the rates of continence

not had a relapse for at least 2 years101. The incidence (78% for patients with neuropathic bladders and 93%

of complications after sacral neuromodulation seems for those with detrusor instability) 3 years after augmen

not to be significantly different from that of the general tation are high, as are the patient satisfaction rates108,109.

population of patients with LUT dysfunctions with no Therefore, augmentation ileocystoplasty is an effective

established neurogenic aetiology103. In a study enrolling surgical approach for patients with multiple sclerosis

NATURE REVIEWS | UROLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 9

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

who also have treatment-refractory neurogenic blad haemorrhagic shock (n = 2), the surgical procedure did

der, provided that patients are able to self-catheterize, significantly improve the mean overall Qualiveen® score

and this approach can improve patients’ LUT-specific (from 2.1 before surgery to 1.16 after surgery; P = 0.02).

quality of life. The investigators found that the postoperative morbid

Augmentation cystoplasty is currently feasible using a ity rate was 18.2%. Interestingly, limitations (1.64 ± 1.38

robot-assisted laparoscopic approach110; although, com before surgery versus 0.60 ± 0.69 after surgery; P = 0.005),

parative studies are needed to confirm the results and the constraints (2.91 ± 1.01 before surgery versus 2.07 ± 0.93

reduced morbidities observed following use of this pro after surgery; P = 0.16) and specific urinary impact index

cedure in comparison with those obtained with the open (1.86 ± 0.96 before surgery versus 1.25 ± 0.71 after sur

approach. Augmentation cystoplasty procedures can also gery; P = 0.024) subscores of the Qualiveen® were sig

be performed concomitantly with a cutaneous continent nificantly improved at 6 months after surgery116. In a

urinary diversion in circumstances where the patient is prospective study, authors reported the quality-of‑life

unable to perform ISC through the urethra. For cosmetic outcomes of 44 patients with multiple sclerosis who

reasons, the umbilicus is often used as the stoma site in underwent laparoscopic ileal conduit surgery to treat

these patients. The short-term continence rates achieved their LUT dysfunction117. The authors found that the

with augmentation cystoplasty in combination with a postoperative morbidity rate was 18.2%. Minor (Clavien

continent urinary diversion are >80% and good protec grade ≤2) and major (Clavien grade ≥3) complications

tion of the upper urinary tract is usually achieved111–113. occurred in 13.6% and 6.8% of patients, respectively.

An improvement in quality of life, as assessed using the Noted complications included asymptomatic ureteroileal

Qualiveen® questionnaire, has also been reported114; stenosis (n = 6) and pyelonephritis (n = 3).

furthermore, the reported rates of continence (86%), as

well as satisfaction with both functional and aesthetic Management of SUI

outcomes (88% and 92%, respectively) are high after a SUI owing to sphincter deficiency that does not respond

mean follow‑up duration of 21.6 months114. However, to behavioural modifications requires a specialised man

all of these patients have a high risk of complications, agement approach. Social continence, where symptoms

including stomal leakage or stenosis. Regular clinician are controlled to the extent that patients’ quality of life

visits to monitor patients’ adherence and continence is largely unaffected, can be achieved by collecting urine

status are, therefore, required. during incontinence episodes using pads, for example.

In our own clinical experience, condom catheters with

Non-continent urinary diversion. Despite the availabil urine collection devices are also a practical method for

ity of procedures to create a catheterizable outlet, some managing SUI in men as these tend to result in fewer

patients remain unable or unwilling to perform ISC. hygiene issues, and are more affordable than pads. Use

Quadriplegia, limited dexterity and/or devastating cog of a penile clamp is contraindicated in patients with

nitive impairment are the main causes of this inability. detrusor overactivity or low bladder compliance owing

In order to restore a low-pressure reservoir without the to the risk of developing high intravesical pressures36.

use of an indwelling urethral, or suprapubic catheter Neurogenic SUI remains a therapeutic challenge: cur

and to improve quality of life, a noncontinent cutan rently, no nonsurgical treatments for this condition exist,

eous diversion using an ileal conduit and a urine collect and the armamentarium for management comprises

ing device can be performed115. Ultimately, use of such midsuburethral synthetic slings, fascial slings, artificial

an approach could be considered in patients who are urinary sphincters, periurethral bulking agents and ure

wheelchair-bound or bedridden (including in those with thral closure116. No published data on neurogenic SUI

skin ulcers), with intractable and/or untreatable incon specifically in patients with multiple sclerosis currently

tinence, in patients with devastating LUT symptoms, exist. Therefore, selection of the most appropriate treat

when the upper urinary tract is severely c ompromised ment should be made on a case‑by‑case basis, consider

or in patients who refuse other therapies. ing the patient’s ability to perform ISC and the extent of

A cystectomy is usually performed as a first-line any cognitive impairment.

approach to prevent pyocystitis. Much of the data on

the outcomes of patients who underwent ileal conduit Management of voiding symptoms

surgery are from patients who underwent this procedure Intermittent catheterization

after pelvic cancer surgery. Regarding patients with ISC is the preferred method for the treatment of incom

neurological diseases, some studies have provided data plete bladder emptying or urinary retention in patients

on the outcomes of ileal conduit surgery among patients with neurogenic bladder35. This approach to manage

with multiple sclerosis. In a retrospective study, investi ment of incomplete bladder emptying was originally

gators reported the functional outcomes of ileal conduit described by Lapides and colleagues118, in 1971, in a

procedures performed in a population of 53 patients woman with multiple sclerosis. ISC has to be initi

with multiple sclerosis with neurogenic bladder116. ated in patients whose incomplete bladder emptying

Despite the fact that ileal conduit surgery was found to is reflected by the presence of a high residual volume.

be associated with substantial perioperative morbidi This high residual volume is generally accepted to be

ties, including blood loss requiring transfusion (n = 17), >100 ml, however the exact volume depends upon the

pneumonia (n = 3), pyelonephritis (n = 3), pelvic abscess characteristics of the individual patient. Actually, no

(n = 1), wall abscess (n = 2), septicaemia (n = 1) and evidence-based cut off post-void residual value exists for

10 | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION www.nature.com/nrurol

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

the recommendation to start clean intermittent catheter should be discussed with the patient and alternatives

ization in patients with multiple-sclerosis-related LUT should be presented; this is a grade A recommendation

dysfunction41. The average frequency of catheterization provided by the EAU35.

per day is 4–6 times, as bladder volume at catheteriza

tion should ideally, as a rule, not exceed 400–500 ml119. Management of DSD

ISC is rarely necessary in the early stages of multiple Urethral sphincterotomy. The main objectives of the

sclerosis but becomes increasingly likely to be needed treatment of DSD are to improve voiding function, to

as a patient’s mobility deteriorates. The introduction of decrease voiding pressures and to avoid the need for

self-catheterization can be challenging in patients with indwelling catheters. However, the possibility of using

multiple sclerosis, therefore, training and support from a condom catheter and the existence of efficient blad

the health-care team is required. The ability of patients der contractions are a prerequisite. Moreover, long-

with multiple sclerosis to learn ISC might be influenced term follow‑up monitoring is absolutely necessary,

by the extent of symptoms, as indicated by the EDSS; by owing to the risk of reflex voiding, leading to a rise in

contrast, cognitive decline seems not to limit a patient’s intravesical pressure, which could potentially damage

ability to learn ISC120. When having to perform ISC, the upper urinary tract. Urethral sphincterotomy, a

patients with multiple sclerosis might face several bar procedure designed to weaken the contractions of the

riers: patient-related factors include physical disabilities urethral sphincter, can be conducted using one of sev

and psychological factors, and external factors include eral different techniques, including laser and electrode

access to public toilets. These factors have to be indi endoscopic sphincterotomy133, sphincteric stent prosthe

vidually addressed121. Use of ISC decreases the risk of sis133 and dilatation using a balloon. Regardless of the

urinary tract infections and upper urinary tract dam technique used, sphincterotomy should only be focused

age, promotes urinary continence and, in some studies, on the striated sphincter. The effectiveness of sphincter

has been demonstrated to improve patients’ quality of otomy has been demonstrated in a prospective study of

life32,122–125. For patients with multiple sclerosis who also patients with DSD owing to spinal cord injury: 83.7%

have severe limb spasticity and poor mobility, a willing of patients had a decrease in voiding pressure, subjective

carer can be taught to catheterize the patient. autonomic dysreflexia was resolved in 93.2% of patients

Some patients are unable to reach their urethra, and febrile urinary tract infections disappeared in 76.7%

which is necessary in order to self-catheterize, owing to of patients134.

limited hand dexterity or other physical limitations, such

as obesity. For such patients, a continent catheterizable BoNT‑A. A few published reports exist from studies

tube is created using various surgical techniques, includ designed to investigate the outcomes of intraurethral

ing the appendix (Mitrofanoff ’s principle) or a portion injections of BoNT‑A for the treatment of DSD. In a

of small intestine (Yang-Monti and Casale’s principles)85. multicentre, randomized double-blind study, investi

Data from a study of a small cohort of patients with gators evaluated the efficacy and safety of 100‑unit

multiple sclerosis reveal that use of α‑adrenoceptor antag injections of BoNT‑A into the striated sphincter as a

onists reduces post-void residual volumes126; although, treatment of DSD in 86 patients with multiple scler

the experience in clinical practice indicates that many osis135. The authors administered the treatment as a

patients fail to derive any consistent benefits from this single transperineal injection using striated sphincter

approach. However, symptoms of poor voiding owing to electromyography: the coaxial needle was inserted on the

outflow obstruction might be caused by prostate enlarge median line 2 cm above the anal margin in men, or in the

ment in men, or a pelvic-organ prolapse in women. The upper external or internal quarter, above the urethral

possible presence of one of these two conditions should meatus in women, thus enabling the striated sphincter

be assessed during initial clinical examination. to be localized135. The injection was delivered after first

having verified that the needle was not inserted into a

Long-term indwelling catheterization blood vessel. Compared with placebo, BoNT‑A injec

For patients with a substantially increased post-void tions significantly increased the voided volume (by 54%;

residual volume who are unwilling or unable to con P = 0.02) and reduced both the premicturition and maxi

duct ISC, or who have incontinence that is refractory mal detrusor pressures (by 29% and 21%, respectively;

to treatment, a long-term indwelling transurethral or both P = 0.02). By contrast, BoNT‑A injections had no

suprapubic catheter is often used to ensure that the significant effect upon post-void residual v olumes and

bladder empties and to provide urinary continence. both treatments were equally well tolerated135.

However, long-term indwelling catheter use “should be Following a randomized-controlled double-blind

avoided when possible” (REF. 35) because this might lead study designed to compare the efficacy and tolerability

to a range of complications including recurrent urinary of transperineal injections of BoNT‑A versus those of

tract infections, catheter blockages, catheter bypass lidocaine, including three patients with multiple scler

ing, urethral destruction, bladder stones and bladder osis in a cohort of 13 patients, investigators reported

cancer127–131. Despite these possible complications, how that post-void residual volume was significantly

ever, long-term catheterization does not substantially decreased (by 141.4 ml 7 days after treatment; P <0.03);

alter a patient’s quality of life132. A suprapubic catheter DSD and patient satisfaction were both improved

is recommended over a transurethral catheter for long- in the BoNT‑A but not in the lidocaine group136. In

term use9,42; however, the potential for complications another report, investigators described similar results

NATURE REVIEWS | UROLOGY ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | 11

©

2

0

1

6

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

in a prospective nonrandomized study with a cohort evaluation is advocated, including use of a 3‑day bladder

of 21 patients, eight of whom had multiple sclerosis137; diary and uroflowmetry with measurement of the post-

however, data from patients with multiple sclerosis void residual volume. The International Francophone

were not analysed separately in this study. Moreover, in Neurourological Expert Study Group20 recommends a

both studies136,137, contrary to the study by Gallien and urodynamic investigation every 3 years, whereas the UK

colleagues135, electromyography was not used to locate consensus on the management of the bladder in multiple

the striated sphincter. Results from studies with small sclerosis recommends urodynamic investigations only in

patient cohorts, which have a high risk of bias relative the event of second-line or intravesical treatment being

to those with larger cohorts, have revealed evidence of required, or when a patient is considered to be at risk of

limited quality, suggesting that intraurethral BoNT‑A damage to the upper urinary tract9.

injections given as a treatment of functional blad For patients who are deemed to have a higher risk of

der outlet obstruction in adults with neurogenic bladder rapid worsening of LUT symptoms, the annual evalu

dysfunction improve certain urodynamic parameters ation should be more complete, and should include ultra

30 days after treatment; these parameters include sonography of the urinary tract, measurement of renal

higher voided urine volumes and lower premaximal creatinine clearance and a quality-of‑life assessment.

and maximal detrusor pressures, as summarized in a The urodynamic follow‑up should be systematic. The

meta-analysis138. In conclusion, only limited evidence specific choice of investigations should be determined

is available to support the use of intraurethral BoNT‑A in discussions among an expert m ultidisciplinary team.

injections in the treatment of DSD in patients with mul

tiple sclerosis. Moreover, the need for reinjections is a Conclusions

major drawback138. LUT symptoms are common in patients with multiple

sclerosis and can negatively affect patients’ quality of

Follow‑up monitoring life. During the early stages of LUT dysfunction, anti

Patients with multiple sclerosis should have their symp muscarinic medications and ISC are the first-line treat

toms reviewed regularly as both the type and severity ments. Treatment pathways are now available that offer

of LUT dysfunction can change with neurological pro guidance on selecting the most appropriate manage

gression9,20,40. Recommendations exist for long-term ment strategy. Patients should be assessed and m anaged

urological follow‑up monitoring, taking into account by health-care professionals with a suitable level of

the presence of specific risk factors: duration of multi experience, who can offer at least one of the number

ple sclerosis >15 years, presence of an indwelling cath of effective treatment options. Long-term monitoring of

eter, ample uninhibited detrusor contractions, high patients with multiple sclerosis is essential as the type

detrusor pressure or DSD9,20,40. For patients who are and severity of LUT dysfunction can change with

risk-free according to these criteria, a systematic annual neurological progression.

1. Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas 11. Hemmett, L., Holmes, J., Barnes, M. & Russell, N. What 21. Panicker, J. & Haslam, C. Lower urinary tract

of MS 2013: mapping multiple sclerosis around the drives quality of life in multiple sclerosis? QJM 97, dysfunction in MS: management in the community.

world. [online], http://www.msif.org/wp-content/ 671–676 (2004). Br. J. Community Nurs. 14, 474–480 (2009).

uploads/2014/09/Atlas-of-MS.pdf (2013). 12. Marrie, R. A., Cutter, G., Tyry, T., Vollmer, T. 22. Mahajan, S. T., Patel, P. B. & Marrie, R. A. Under

2. Confavreux, C., Aimard, G. & Devic, M. Course and & Campagnolo, D. Disparities in the management treatment of overactive bladder symptoms in

prognosis of multiple sclerosis assessed by the of multiple sclerosis-related bladder symptoms. patients with multiple sclerosis: an ancillary analysis

computerized data processing of 349 patients. Neurology 68, 1971–1978 (2007). of the NARCOMS Patient Registry. J. Urol. 183,

Brain J. Neurol. 103, 281–300 (1980). 13. Mayo, M. E. & Chetner, M. P. Lower urinary tract 1432–1437 (2010).

3. Kutzelnigg, A. et al. Cortical demyelination and dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Urology 39, 67–70 23. Araki, I., Matsui, M., Ozawa, K., Takeda, M.

diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. (1992). & Kuno, S. Relationship of bladder dysfunction to

Brain J. Neurol. 128, 2705–2712 (2005). 14. Giannantoni, A. et al. Urological dysfunctions and upper lesion site in multiple sclerosis. J. Urol. 169,

4. Furby, J. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging measures urinary tract involvement in multiple sclerosis patients. 1384–1387 (2003).

of brain and spinal cord atrophy correlate with clinical Neurourol. Urodyn. 17, 89–98 (1998). 24. Porru, D. et al. Urinary tract dysfunction in multiple

impairment in secondary progressive multiple 15. Koldewijn, E. L., Hommes, O. R., Lemmens, W. A. J. G., sclerosis: is there a relation with disease-related

sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 14, 1068–1075 (2008). Debruyne, F. M. J. & Van Kerrebroeck, P. E. V. parameters? Spinal Cord 35, 33–36 (1997).

5. Kurtzke, J. F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple Relationship between lower urinary tract abnormalities 25. Ciancio, S. J., Mutchnik, S. E., Rivera,

sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). and disease-related parameters in multiple sclerosis. V.M. & Boone, T. B. Urodynamic pattern changes in

Neurology 33, 1444–1452 (1983). J. Urol. 154, 169–173 (1995). multiple sclerosis. Urology 57, 239–245 (2001).

6. Derfuss, T., Bergvall, N. K., Sfikas, N. & Tomic, D. L. 16. Gallien, P. et al. Vesicourethral dysfunction and 26. Giannantoni, A. et al. Lower urinary tract dysfunction

Efficacy of fingolimod in patients with highly active urodynamic findings in multiple sclerosis: a study and disability status in patients with multiple

relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Curr. Med. Res. of 149 cases. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 79, 255–257 sclerosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 80, 437–441

Opin. 31, 1687–1691 (2015). (1998). (1999).

7. Nortvedt, M. W. et al. Prevalence of bladder, bowel 17. Kasabian, N. G., Krause, I., Brown, W. E., Khan, Z. 27. De Ridder, D. et al. Bladder cancer in patients with

and sexual problems among multiple sclerosis & Nagler, H. M. Fate of the upper urinary tract in multiple sclerosis treated with cyclophosphamide.

patients two to five years after diagnosis. Mult. Scler. multiple sclerosis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 14, 81–85 J. Urol. 159, 1881–1884 (1998).

13, 106–112 (2007). (1995). 28. Desgrippes, A., Meria, P., Cortesse, A.,