Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pre-Monarchical Social Institutions in Israel in The Light of Marl

Uploaded by

rico neksonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pre-Monarchical Social Institutions in Israel in The Light of Marl

Uploaded by

rico neksonCopyright:

Available Formats

PRE-MONARCHICAL SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

IN ISRAEL IN THE LIGHT OF MARl

by

ABRAHAM MALAMAT

Jerusalem

In recent years it has again become fashionable, in some quarters, to

discredit the historical reliability of various biblical descriptions of pre-

monarchic institutions in Israel. In order to counteract such scepticism

we may adduce a number of biblical references to early social and legal

practices which point to the existence of legitimate pre-monarchical

institutions. Thus, for example, we see evidence of an ancient family law,

including inheritance provisions and marriage customs, in other words,

a law not royal in authority. We note the recruitment of troops along

gentilic lines, from individual settlements, rather than the formation of

a national army. In short, it is the life of the family or clan that is domi-

nant here and not the later royal system. An indication of a different sort

can be found in the so-called anti-monarchic pericopes within the Bible,

several of which no doubt draw their inspiration from pre-monarchical

times. Finally - and this will be our major argument - there is the

extra-biblical evidence, and in this context the Mari documents are of

prime importance.

Old Babylonian Mari apparently shared common origins with the

early Israelites as well as with many other West Semitic peoples. Thus,

a comparison between early Israel and Mari can and should be made.

Indeed, the broad spectrum of the Mari archives - the largest extra-

biblical body of material within the West Semitic milieu - actually

invites such a comparison.! Furthermore, this comparative study reveals

an aggregate of similarities which thus cannot simply be regarded as a

result of common patterns of human behaviour.

First and foremost in such a comparison is the linguistic factor, that

is, the lexical items which are parallel in the corpora of both Mari and

the Bible. Significantly, a perusal of such West Semitic terminology has

1 On the comparative approach, including similarities as well as contrasts, see my brief

remarks in "Mari and Early Israel", Biblical Archaeology Today. Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Congress on Biblical Archaeology Uerusalem, 1985), pp. 235-43. On the method in

general see I. J. Gelb, "Comparative Method in the Study of the Society and Economy

of the Ancient Near East", Rocznik Orientalistyczny 41 (1980), pp. 24-36.

166 A. MALAMAT

its major impact on the societal level and reflects, in one way or another,

a thoroughly tribalistic milieu, mainly of non-urban population. This is

so in Mari as well as in early Israel, and it is only through sources

associated with these two entities - in all documentary evidence of the

ancient Near East until Islamic times - that tribal society is manifested

in full bloom.

The terminology is unique to the Akkadian of Mari and to Hebrew,

although occasionally it is found in other West Semitic languages as well

(in particular, Ugaritic, Aramaic and Arabic), but there are no true

cognates in standard Akkadian. At Mari the referents are entirely foreign

to the Assyro-Babylonian milieu. The Mari documents contain a set of

West Semitic terms denoting tribal units, forms of tribal settlements and

tribal leadership, in short: tribal institutions and customs. A comparative

study of these terms with their Hebrew cognates not only sheds light on

the meaning of individual words but also serves to illuminate the

underlying structures and institutions of the societies involved. We

employ the concept of institution in a broad sense encompassing inter alia

various life-styles. Let us first enumerate the Mari-Bible equivalents in

the various social realms: tribal units - gii)umlgiiyumlhibrumlummatum -

Hebrew goy, ~eber, )ummiih; forms of settlement - nawumlha~iirum -

niiweh, ~ii~er; and finally the institution of patrimony - nihlatum -

Hebrew na~aliih. We shall not deal here with terms for tribal leadership

- siipi/umlmerhum - sope.t, merea c - since they have been the subject of

several recent satisfactory discussions. 2

giiyumlgii)um - goy3

We shall commence our discussion with the term for the tribal unit

giiyum, Hebrew gOy, which was relatively small in scope. In Mari we

witness the occurrence of personal names composed of giiyum as well, in

particular Bahlu-giiyim (the leader of a clan notably named Amurru; see

below). In addition to Mari, giiyum is now also confirmed by a single

occurrence in the contemporary texts of Tell Rimah (ancient Karana).4

2 See]. Safren, "New Evidence for the Title of the Provincial Governor", RUCA 50

(1979), pp. 1-15; idem, "meraum and merautum in Mari" , Orientalia, N.S. 51 (1982), pp.

1-29.

3 See my previous treatments of giiyumlgoy inJAOS 82 (1962), pp. 143-4, n. 3; 15 e Ren-

contre Assyriologique Internationale, Comptes rendus (Liege, 1967), pp. 133 ff.; most recently

cf. Ph. Talon in]. M. Durand and].-R. Kupper (ed.), Miscellanea Babylonica (Milanges

M. Birot) (Paris, 1985), pp. 277-84; and G.]. Botterweck, R. E. Clements, ThWAT 1

(1973), cols 965-73 (s.v. goy).

4 See S. Dalley et alii, The Old Babylonian Tabletsfrom Tell al Rimah (Hertford, 1976),

pp. 220-1 (no. 305:18).

You might also like

- Laws in The Hebrew Bible Old TestamentDocument30 pagesLaws in The Hebrew Bible Old TestamentIJNo ratings yet

- Goal and Scope of PsychotherapyDocument4 pagesGoal and Scope of PsychotherapyJasroop Mahal100% (1)

- "Commanded War": Three Chapters in The "Military" History of Satmar HasidismDocument46 pages"Commanded War": Three Chapters in The "Military" History of Satmar HasidismHirshel TzigNo ratings yet

- Keys To The Ultimate Freedom PDFDocument245 pagesKeys To The Ultimate Freedom PDFdebtru100% (2)

- Fisher Fieldbus6200Document340 pagesFisher Fieldbus6200Arun KumarNo ratings yet

- Janzen Lemba 1982 3of5Document212 pagesJanzen Lemba 1982 3of5J. LeonNo ratings yet

- The God of The HabiruDocument24 pagesThe God of The Habiruredwasp_korneelNo ratings yet

- Kaldellis Romanland PDFDocument393 pagesKaldellis Romanland PDFVarga Bennó100% (3)

- A Zimbabwean PastDocument5 pagesA Zimbabwean PastJonathan ZilbergNo ratings yet

- Ancient Israel HistoryDocument425 pagesAncient Israel HistorySTROWS100% (1)

- Imperial Cult SourcesDocument5 pagesImperial Cult SourcesDavid DuttonNo ratings yet

- Early Old Babylonian Amorite Tribes and Gatherings and The Role of Sumu-AbumDocument17 pagesEarly Old Babylonian Amorite Tribes and Gatherings and The Role of Sumu-AbumSongNo ratings yet

- Aura and Chakra 3Document88 pagesAura and Chakra 3Theodore Yiannopoulos100% (2)

- Book of History Vol VDocument448 pagesBook of History Vol VTariq720100% (1)

- Study Abroad Consultant in PanchkulaDocument17 pagesStudy Abroad Consultant in Panchkulashubham mehtaNo ratings yet

- Legends of Babylon and Egypt in Relation to Hebrew TraditionFrom EverandLegends of Babylon and Egypt in Relation to Hebrew TraditionNo ratings yet

- Giordano Bruno and The RosicruciansDocument11 pagesGiordano Bruno and The RosicruciansGuido del GiudiceNo ratings yet

- Sufism in Somaliland A Study in Tribal Islam - I By: I.M. LewisDocument23 pagesSufism in Somaliland A Study in Tribal Islam - I By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-Misri100% (1)

- The Babylonian Talmud in Its Historical Context - ElmanDocument9 pagesThe Babylonian Talmud in Its Historical Context - ElmanDonna HallNo ratings yet

- Seth Schwartz - The Patriarchs and The DiasporaDocument15 pagesSeth Schwartz - The Patriarchs and The DiasporaGabriel ReisNo ratings yet

- The Polemic Nature of Genesis CosmologyDocument22 pagesThe Polemic Nature of Genesis CosmologyIulianPNo ratings yet

- Politics, Conflict, and Movements in First-Century PalestineFrom EverandPolitics, Conflict, and Movements in First-Century PalestineNo ratings yet

- Cubex 6200 Spec Sheet PDFDocument4 pagesCubex 6200 Spec Sheet PDFtharciocidreira0% (1)

- Migrating Tales: The Talmud's Narratives and Their Historical ContextFrom EverandMigrating Tales: The Talmud's Narratives and Their Historical ContextNo ratings yet

- COT 1 - (Science 7) - Cell To Biosphere 4as Semi-Detailed LPDocument10 pagesCOT 1 - (Science 7) - Cell To Biosphere 4as Semi-Detailed LPARLENE AGUNOD100% (1)

- Fugiamus Ergo ForumDocument13 pagesFugiamus Ergo ForumdavidnatalNo ratings yet

- Muslim - Jewish Relations - Oxford - ResearchDocument25 pagesMuslim - Jewish Relations - Oxford - ResearchNjono SlametNo ratings yet

- Women and Medieval Western Europe.Document11 pagesWomen and Medieval Western Europe.Nikesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Muslim Kingship Power and The Sacred in Muslim Christian and Pagan Polities 1860646093 9781860646096 CompressDocument314 pagesMuslim Kingship Power and The Sacred in Muslim Christian and Pagan Polities 1860646093 9781860646096 CompressOct888No ratings yet

- Carr Conway - Introduction To The Bible - Chapter 03Document33 pagesCarr Conway - Introduction To The Bible - Chapter 03esonamtsoloNo ratings yet

- Adam H. Becker, Reuven Kiperwasser - Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians. Religious Dynamics in A Sasanian Context (Judaism in Context) (Retail) - 7-26Document20 pagesAdam H. Becker, Reuven Kiperwasser - Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians. Religious Dynamics in A Sasanian Context (Judaism in Context) (Retail) - 7-26Vale PepinoNo ratings yet

- Prophecy and Politics in The Old TestamentDocument12 pagesProphecy and Politics in The Old TestamentKudzaisheFaith MuchanyereyiNo ratings yet

- Judaism and The World: The Holy and The Profane: Religion in World AffairsDocument25 pagesJudaism and The World: The Holy and The Profane: Religion in World AffairsPaskah Parlaungan PurbaNo ratings yet

- God's Alliance With ManDocument21 pagesGod's Alliance With ManFaiver MañoscaNo ratings yet

- Article 149Document29 pagesArticle 149johnfanteNo ratings yet

- Middle East FinalDocument8 pagesMiddle East Finalapi-667132918No ratings yet

- Rabbinic Literature: Schürer, History of The Jewish People, 1:553Document2 pagesRabbinic Literature: Schürer, History of The Jewish People, 1:553Stone JusticeNo ratings yet

- Aksum As Seedbed Society 2010aDocument11 pagesAksum As Seedbed Society 2010aGiday Gebrekidan100% (1)

- JAAR 51.4 (1983), Procreation, Production, and Protection. Male-Female Balance in Early IsraelDocument25 pagesJAAR 51.4 (1983), Procreation, Production, and Protection. Male-Female Balance in Early IsraelKeung Jae LeeNo ratings yet

- Chiasmus in The Book of MormonDocument15 pagesChiasmus in The Book of MormonsouzafreakingNo ratings yet

- 5Document29 pages5BenjaminFigueroaNo ratings yet

- W. Lee Humphreys - The Early History of God - Yahweh and The Other Deities in Ancient Israel by Mark S. Smith (Journal of The American Academy of Religion, 61, 1, 1993) PDFDocument5 pagesW. Lee Humphreys - The Early History of God - Yahweh and The Other Deities in Ancient Israel by Mark S. Smith (Journal of The American Academy of Religion, 61, 1, 1993) PDFcarlos murciaNo ratings yet

- Janzen Lemba 1982 3of5Document212 pagesJanzen Lemba 1982 3of5Sergio JituNo ratings yet

- Shapira, Haim - Las Escuelas de Hillel y ShamaiDocument57 pagesShapira, Haim - Las Escuelas de Hillel y ShamaiManhate ChuvaNo ratings yet

- Did The Rabbis Believe in Agreus Pan Rabbinic Relationships With Roman Power Culture and Religion in Genesis Rabbah 63Document26 pagesDid The Rabbis Believe in Agreus Pan Rabbinic Relationships With Roman Power Culture and Religion in Genesis Rabbah 63tabickNo ratings yet

- TXPVPL Tba Tybl Yawrq Kta WDM (Y Rva: Heroic Leadership in The WildernessDocument29 pagesTXPVPL Tba Tybl Yawrq Kta WDM (Y Rva: Heroic Leadership in The WildernessJulio ZabatieroNo ratings yet

- The Ancestral HistoryDocument5 pagesThe Ancestral HistoryBea TumulakNo ratings yet

- The Polity in Biblical IsraelDocument4 pagesThe Polity in Biblical IsraelRoderick kasoziNo ratings yet

- Elijah and Elisha Within The Argument of KingsDocument64 pagesElijah and Elisha Within The Argument of KingsBanks CorlNo ratings yet

- 75807-Skrynnikova-Mongolian Nomadic Society of Empire Period-A011Document11 pages75807-Skrynnikova-Mongolian Nomadic Society of Empire Period-A011Rodrigo Méndez LópezNo ratings yet

- Summary For Ruth Chronicles DillardDocument3 pagesSummary For Ruth Chronicles DillardJesse Amiel Aspacio-Ruiz RamosoNo ratings yet

- Friedman - JBL Review of The Rise of Yahwism The Roots of Israelite Monotheism, by de Moor The Early History of God by SmithDocument7 pagesFriedman - JBL Review of The Rise of Yahwism The Roots of Israelite Monotheism, by de Moor The Early History of God by Smithwhiskyagogo1No ratings yet

- Byrne RefugeDocument31 pagesByrne RefugeRyan ByrneNo ratings yet

- The Iranian Talmud:: Shai Secunda The Martin Buber Society of FellowsDocument29 pagesThe Iranian Talmud:: Shai Secunda The Martin Buber Society of FellowsIbrahim Ben IaqobNo ratings yet

- Mazower, Mark. A Nova Ordem de HitlerDocument17 pagesMazower, Mark. A Nova Ordem de HitlerPRISCILA DE LIMANo ratings yet

- AZMEH, Aziz Al. (2014) The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity. Allah and His People, Cap.03Document64 pagesAZMEH, Aziz Al. (2014) The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity. Allah and His People, Cap.03Juan Manuel PanNo ratings yet

- Attitudes Toward Deviant Sex in Ancient MesopotamiaDocument21 pagesAttitudes Toward Deviant Sex in Ancient Mesopotamiamark_schwartz_41No ratings yet

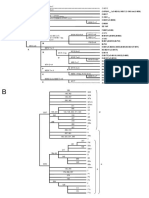

- Mbe 08 0888 File013 - msp097Document2 pagesMbe 08 0888 File013 - msp097rico neksonNo ratings yet

- Ambon - Saparua Language PDFDocument184 pagesAmbon - Saparua Language PDFrico neksonNo ratings yet

- msl093FigS1 RevisedDocument1 pagemsl093FigS1 Revisedrico neksonNo ratings yet

- Archaeology in Oceania - 2019 - POSTH - Response To Ancient DNA and Its Contribution To Understanding The Human History ofDocument5 pagesArchaeology in Oceania - 2019 - POSTH - Response To Ancient DNA and Its Contribution To Understanding The Human History ofrico neksonNo ratings yet

- Kunlun and Kunlun Slaves As Buddhists in The Eyes of The Tang ChineseDocument26 pagesKunlun and Kunlun Slaves As Buddhists in The Eyes of The Tang Chineserico neksonNo ratings yet

- Nebel HG 00 IPArabsDocument12 pagesNebel HG 00 IPArabsrico neksonNo ratings yet

- In The Oral Traditions of The Maluku People: "Pasawari Kunci Negeri" Tracking The Value of Religious ModerationDocument18 pagesIn The Oral Traditions of The Maluku People: "Pasawari Kunci Negeri" Tracking The Value of Religious Moderationrico neksonNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document305 pagesFULLTEXT01rico neksonNo ratings yet

- Local and Scientific Understanding of Forest DiverDocument35 pagesLocal and Scientific Understanding of Forest Diverrico neksonNo ratings yet

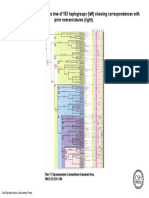

- Genome Res. 2002 Feb 12 (2) 339-48, Figure 1Document1 pageGenome Res. 2002 Feb 12 (2) 339-48, Figure 1rico neksonNo ratings yet

- Price List 2020-21Document3 pagesPrice List 2020-21Nikhil SalujaNo ratings yet

- DLP Geothermal Power PlantDocument4 pagesDLP Geothermal Power PlantRigel Del CastilloNo ratings yet

- Ryan PrintDocument24 pagesRyan PrintALJHON SABINONo ratings yet

- Set A Hello 95: Indicate Whether The Sentence or Statement Is True or FalseDocument2 pagesSet A Hello 95: Indicate Whether The Sentence or Statement Is True or FalseJohn AztexNo ratings yet

- UMG 512 ProDocument12 pagesUMG 512 Propuikmutnb2No ratings yet

- Work of ArchDocument5 pagesWork of ArchMadhu SekarNo ratings yet

- XMLReports DownloadattachmentprocessorDocument44 pagesXMLReports DownloadattachmentprocessorjayapavanNo ratings yet

- Rtu2020 SpecsDocument16 pagesRtu2020 SpecsYuri Caleb Gonzales SanchezNo ratings yet

- Innovative Injection Rate Control With Next Generation Common Rail Fuel Injection SystemDocument8 pagesInnovative Injection Rate Control With Next Generation Common Rail Fuel Injection SystemRakesh BiswasNo ratings yet

- Oglej Case Study 4300 1Document20 pagesOglej Case Study 4300 1api-533010905No ratings yet

- Howo SCR Tenneco. ManualDocument42 pagesHowo SCR Tenneco. Manualulyssescurimao1No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Intro To QualityDocument34 pagesChapter 1 Intro To QualityRonah Abigail BejocNo ratings yet

- Sci8 Q4 M4 Classifications-of-Living-OrganismsDocument27 pagesSci8 Q4 M4 Classifications-of-Living-OrganismsJeffrey MasiconNo ratings yet

- Introduction Manual: 30000mah Type-C Power BankDocument33 pagesIntroduction Manual: 30000mah Type-C Power BankIreneusz SzymanskiNo ratings yet

- 9ER1 Question BookletDocument16 pages9ER1 Question BookletCSC TylerNo ratings yet

- s1 English Scope and Sequence ChecklistDocument18 pagess1 English Scope and Sequence Checklistapi-280236110No ratings yet

- ASV Program Guide v3.0Document53 pagesASV Program Guide v3.0Mithun LomateNo ratings yet

- WWW - Universityquestions.in: Question BankDocument11 pagesWWW - Universityquestions.in: Question BankgokulchandruNo ratings yet

- International Strategies Group, LTD v. Greenberg Traurig, LLP Et Al - Document No. 74Document8 pagesInternational Strategies Group, LTD v. Greenberg Traurig, LLP Et Al - Document No. 74Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 Assessment Guidance 2021-2022Document13 pagesUnit 7 Assessment Guidance 2021-2022JonasNo ratings yet

- Measure and IntegralDocument5 pagesMeasure and Integralkbains7No ratings yet

- Criminal Law - Aggravating CircumstancesDocument9 pagesCriminal Law - Aggravating Circumstancesabo8008No ratings yet