Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Capitulo 1

Capitulo 1

Uploaded by

Ramon Arthur0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views6 pagesThis chapter discusses the significance of property ownership and its relationship to human existence. It argues that all living things require some form of property relationship for survival, and that property ownership is one of the most fundamental facts of human life. The desire to own property stems from humans' longing for individual identification and possession of admired items. While early philosophers acknowledged man's primacy over property, they viewed the desire to own as an undesirable trait and property as an impediment to understanding the true nature of life. This led to an oversimplification of the role of property and ownership in human living.

Original Description:

Original Title

capitulo 1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis chapter discusses the significance of property ownership and its relationship to human existence. It argues that all living things require some form of property relationship for survival, and that property ownership is one of the most fundamental facts of human life. The desire to own property stems from humans' longing for individual identification and possession of admired items. While early philosophers acknowledged man's primacy over property, they viewed the desire to own as an undesirable trait and property as an impediment to understanding the true nature of life. This led to an oversimplification of the role of property and ownership in human living.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views6 pagesCapitulo 1

Capitulo 1

Uploaded by

Ramon ArthurThis chapter discusses the significance of property ownership and its relationship to human existence. It argues that all living things require some form of property relationship for survival, and that property ownership is one of the most fundamental facts of human life. The desire to own property stems from humans' longing for individual identification and possession of admired items. While early philosophers acknowledged man's primacy over property, they viewed the desire to own as an undesirable trait and property as an impediment to understanding the true nature of life. This led to an oversimplification of the role of property and ownership in human living.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Chapter I

Property and Ownership

The significance of property ownership has rarely been fully ap-

preciated. All sentient life is concerned with property, either in-

stinctively or rationally. No organism capable of volitional action

can escape the demands arising within it for some kind of property

relationship. Survival of all beings capable of consciousness is predi-

cated directly upon some kind of property relationship.

Simple forms of life are propelled instinctively toward food,

which they possess and ingest. Possession is a property relationship.

Complex forms of life are guided, partly by instinct and partly by

rational processes, toward the mastery of their environment which

occurs when property is acquired and utilized. A propertyless liv-

ing organism is inconceivable.

Man, the most complex of all living creatures, has the most

numerous and varied demands to express in relation to property.

Guided by reason or by a few residual instinctive drives, man dom-

inates his environment more than any other living thing. His mas-

tery of environment is primarily if not totally a matter of property

acquisition and utilization.

Since the concern of this study relates entirely to man's well-be-

ing, and is not concerned with the well-being of other living things,

the approach here will be to develop a philosophy of property own-

ership within a human context. Since virtually all struggle for exist-

ence and for improving the conditions of existence deals directly or

indirectly with property, this philosophy must include an examina-

tion of the gigantic role property plays in human living. Any phil-

osophy must include an examination of the facts and principles of

reality, and since property comprises an order of fact and principle

of overwhelming magnitude, no philosophy of practical significance

can overlook this area. Nearly all philosophical studies up to the

present time have concentrated their inquiry in the theological,

1

2 THE PHILOSOPHY OF OWNERSHIP

mystical, and metaphysical realms, seeking to probe the mystery of

life's origins and to chart the methods and epistemology of knowl-

edge, yet circumventing the question of property or, at best, skim-

ming briefly over the surface.

One of the obvious reasons for this avoidance appears to be the

very early assumption that property and property relationships were

somehow crass and materialistic. The yearning of the early lovers

of wisdom was for an unfoldment of the real character of life. Prop-

erty was viewed more or less as impedimentia. But this is prob-

ably because the early tendency was to look at property as "things,"

or simply as land, and to fail to realize that the desire and drive

for property, the yearning for ownership, is one of the most funda-

mental facts of life. Human beings long for personal and individual

identification. The desire to own property contains the concept of

exclusiveness, of individualization. Ownership is an expression of

this longing. Human beings long to possess items which they ad-

mire and appreciate. Conceivably, love, recognized as fundamental

with humans, is somehow related to this deeply imbedded drive to

possess, to own, to master personally, to exclude the rest of the

world.

Property viewed as the object or objects of man's drive to own, is

of far less importance than the drive itself. To own, to possess, to

control and master, to acquire and utilize—these motivations are

basic to man. The objects of these drives vary and are essentially

incidental to them, many different kinds of property serving satis-

factorily as the targets for men's yearnings.

Had the attention of the early savants focused primarily upon the

human propensity to own, they might have recognized its funda-

mental nature. Instead, they focused upon the objects to be owned,

the "things," which were deemed of less importance than man. Thus,

in early efforts to understand, property and ownership meant the

same thing. Property (the item to be owned) and ownership (the

act of owning) were somehow indiscriminately merged, which led

to oversimplifications and devious thinking. V^hile these philoso-

phers evaluated correctly the primacy of man in relation to prop-

erty, they considered man's yearning to possess it an undesirable

trait which superior men could and would sublimate.

This type of reasoning is implicit in Plato's Republic; the Stoics

adopted it.1 The Epicureans, who rejected the proposition and re-

1

Whitney J. Oates (ed.), The Stoic and Epicurean Philosophers (New York:

Random House, 1940).

PROPERTY AND OWNERSHIP 3

versed it, were viewed as hedonistic or as gross sensualists. Chris-

tianity, which borrowed so much from both Plato and the Stoics,

carried forward the idea that virtue was somehow related to proper-

tylessness; the poor were in a more favored position because they

were not burdened with possessions. To follow the Master, one was

admonished to give away what he possessed.

Buddhism, which preceded Christianity, proposed that it is desire

itself which constitutes man's major problem. It is not enough

to abandon property; mental and emotional discipline must be im-

posed to the point where the individual loses all desire. Nirvana,

the state of transcendent nothingness, arrives only for the individual

who has stopped all yearning, including even the yearning for

Nirvana.

After the study of economics had been organized and its first

monumental work published,2 economic examination was viewed

by Carlyle as "the dismal science." What could be less inspiring

than an examination of the physical facts of reality dealing with

production and distribution? But the economists, too, tended to

overlook the significance of ownership. They became engrossed in

property itself, as well as its utilization. Most of them became pre-

occupied with statistics in an effort to prove either that there are

natural laws which govern the flow of goods and services in the

market, or that there are no such natural laws.

Criticism of the classical economists is not intended. They pointed

out that man is acquisitive, that his wants are apparently insatiable,

that he will struggle, indeed, he must struggle for the scarce items

that make survival possible. But the classicists, along with many

others, called for a central agency of force to regulate man and his

relationships to property. Man's desire to own was viewed as both

a natural endowment and something that was fraught with much

danger.

In all this, men were viewed as either workers and laborers, or as

consumers. Those few who served as capitalists and entrepreneurs

were rarely recognized for what they were, merely specialized kinds

of workers or consumers. Almost all men play both roles, serving

as producers and then as consumers. Workers, entrepreneurs, capi-

talists—producers all—unite in being consumers. But popular mis-

conceptions placed capitalists and entrepreneurs in a separate cate-

gory, under the supposition that they were extracting wealth or

2

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations (1776).

4 THE PHILOSOPHY OF OWNERSHIP

money from the market and hence preventing workers as well as

consumers from their full and deserved rewards. The argument

became heated and political. Less and less thought was given to

the nature of man as an owner, and more and more thought was

given to amounts of property owned and to the social and collective

implications of scarce amounts of property (poverty) and abundant

amounts of property (riches).

Man's true role as an owner was first glimpsed by the Austrians

who, in developing the theory of marginal utility, recognized that

value is a peculiarly human characteristic placed upon items of

property, having little to do with production or the costs of produc-

tion. Praxeologists have emphasized that it is acting man who must

be understood. But even here, a search into the desire to own has

faltered, for again more attention has pursued property, and its ebb

and flow in relation to supply and demand. The nature of prop-

erty, its acquisition, development, production, distribution, main-

tenance, preservation, and protection must not be overlooked. But

the first and most important effort must be made to separate prop-

erty from ownership, which is a relationship between man, the

owner, and property, the item to be owned.

Property is anything that is subject to ownership. Property exists

whether owned or not. In a virgin area, where men have not yet

penetrated, the land and all the natural appurtenances are property.

The advent of man does not change the character of the land, as

property. But the relationship of the land to man does change

when men acquire this land. I would identify this kind of property

before the appearance of an owner as unowned property. I would

similarly identify items in discard, which men have once owned

and which they now disclaim.

A second classification of property encompasses property that is

correctly owned. In this relationship an owner (man) has assumed

sovereign control over that property which he claims as his own.

Assuming that there are no prior or rival claims to the proper-

ty, and thus decisions respecting the property derive from the

authority of the rightful owner, and assuming that the exercise of

authority is limited to the property owned, then the ownership is

complete and a condition of correct or proper ownership ensues.

A third classification is property that is incorrectly owned.

1. A man may presume to own something that is not property,

2. A man may acquire ownership of a property through theft or

fraud wherein the rightful owner is deprived of what is his through

PROPERTY AND OWNERSHIP 5

the establishment of a conflicting claim resting solely upon the phys-

ical possession or control of the property, but denying the rightful

claim of the real owner.

3. A man may acquire a property, paying for it in full, yet find

that another man or a group of men, who have not paid for the

property, are empowered to interfere with his sovereign control of

the property, thus denying his authority over what he owns.

The search for a single word that conveys the meaning intended

insofar as incorrect ownership is concerned has been fruitless. The

person or institution that possesses property through force or fraud

can, after possession becomes a fact, act as though the property thus

acquired were correctly owned. A contest over its control may or

may not ensue, depending on legal or compulsory intervention. But

the property acquired by force or fraud does not retain some special

characteristic that makes it possible for us, upon seeing it, to de-

clare unequivocally, "That property is not correctly owned." The

onus of theft, fraud, or force attaches to persons, not to property.

Property remains innocent.

All property is subject to sovereign control by some human being.

Someone somewhere has the ultimate decision-making power.

When the claimant to property has paid for the property in full or

has rightfully acquired the property through first claim, sovereign

control rightfully belongs to him. If a man or an agency exists to

which the owner must repair for permission to use his property as

he wishes, or to dispose of it as he sees fit, then in fact he is not the

sovereign owner, but some other man or agency has sovereign con-

trol.

In the present age, a discussion of the ownership of property

is vital. For many years it was supposed that conflicting ideologies

disputed the question as to whether a system of capitalism would

pertain. Socialism was viewed as the antithesis of capitalism. But

this question has long since been settled. Capitalism will survive.

By capitalism is meant an economic system in which wealth, in the

form either of natural resources or of manufactured goods, can be

employed for the production of more wealth. There is no longer a

question plaguing humanity at this point. Wealth will be employed

in the production of further wealth. The question that remains to

be answered relates to the ownership of wealth.

Is wealth to be owned by private persons who will manage wnat

they own (private capitalism)? Or is wealth to be taken from pri-

vate persons under one pretext or another, and collectively owned

6 THE PHILOSOPHY OF OWNERSHIP

and managed (state capitalism)? Or is wealth to be retained in a

kind of ownership by private persons, but its management relegated

to collective groups, either governmental or otherwise, which, while

not owning, may exercise certain prerogatives of ownership (mixed

capitalism — fascism)?

If a system of private capitalism exists, it must be founded upon

private ownership and management of the tools of production and

distribution. In a word, capital goods (entrepreneurial) are to.be

retained and controlled by private persons.

Socialism, either wholly or in part, champions the abolition of

private ownership of the tools of production and distribution. Pri-

vate property of a non-productive character may remain, but pro-

ductive goods (capital goods) are to be owned and controlled by

the state or by some other collective agency (not a privately owned

corporation) under some type of centrally planned economy.

There is a particularly popular brand of socialism now prevalent

which is usually classed as fascism. Fascism is "national socialism"

(nazi-ism) in which the uses and management of property have

been nationalized (socialized) while private ownership shorn of its

management and regulatory functions, continues.

In all types of socialism, the good of the social whole is sought.

Individual rights to property may be abrogated at any time by the

controlling group. A centrally planned economy is implicit with

private ownership limited to consumer goods.

It is instructive that in those nations which have adopted socialism

either under a communist banner or the banner of a welfare state,

a kind of state capitalism ensues. Government becomes ever more

active as a partner in economic matters, serving as producer, manu-

facturer, distributor, and financier. Thus socialism does not lead to

the abolition of capitalism; it leads to the abolition of the private

ownership and management of capital goods.

The correct antonym of socialism is individualism. In an econom-

ic system of individualism, private ownership and management of

the tools of production, distribution, and finance would be pre-

served.

You might also like

- Vibrant Matter A Political Ecology of ThingsDocument202 pagesVibrant Matter A Political Ecology of ThingsDaniel Barbe Farre93% (15)

- JPU 2 Person LawDocument6 pagesJPU 2 Person LawAshaselenaNo ratings yet

- Tithe - Percentage Giving ChartDocument1 pageTithe - Percentage Giving ChartRay Anthony Rodriguez0% (1)

- Definition and Concept of PropertyDocument7 pagesDefinition and Concept of PropertyVivek SaiNo ratings yet

- Property Law NotesDocument7 pagesProperty Law Notesadv.niveditharajeeshNo ratings yet

- PropertyDocument31 pagesPropertyHarsh MangalNo ratings yet

- Margaret Jane RadinDocument32 pagesMargaret Jane Radinthornapple25No ratings yet

- Modul 1 Property and Easement ActDocument18 pagesModul 1 Property and Easement ActSharvari PurandareNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Part 3Document7 pagesModule 5 Part 3Piyush KrantiNo ratings yet

- Faisal English Jurisprudence Assignment.Document15 pagesFaisal English Jurisprudence Assignment.mail.information0101No ratings yet

- John Locke's Defense of A Society Based On Private PropertyDocument12 pagesJohn Locke's Defense of A Society Based On Private PropertyKris KimNo ratings yet

- PropertyDocument19 pagesPropertymonkeydketchumNo ratings yet

- 2 - What Is PropertyDocument21 pages2 - What Is PropertyjinNo ratings yet

- Property Theory - Lecture - 2Document23 pagesProperty Theory - Lecture - 2Antony PeterNo ratings yet

- Marxist and Liberal Theories On PropertyDocument18 pagesMarxist and Liberal Theories On PropertyBishwa Prakash BeheraNo ratings yet

- Property Law Report 2023Document6 pagesProperty Law Report 2023Ashwin Sri RamNo ratings yet

- Coloniality K - Northwestern 2021Document84 pagesColoniality K - Northwestern 2021Jumico EviNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Private PropertyDocument7 pagesAn Analysis of Private PropertySudharshini KumarNo ratings yet

- JurisprudenceDocument12 pagesJurisprudencelakshya agarwalNo ratings yet

- Justice - An Eternal Quest. by Justice N.J. Pandya (Ret.)Document6 pagesJustice - An Eternal Quest. by Justice N.J. Pandya (Ret.)Pranav PandyaNo ratings yet

- P An Ja Bi: Are There Inanimate Things in Which It Should Not Be Possible To Have Ownership or Other Legal Rights?Document4 pagesP An Ja Bi: Are There Inanimate Things in Which It Should Not Be Possible To Have Ownership or Other Legal Rights?api-661289151No ratings yet

- Final Project IN Philo: Richmond Lance C. AguasDocument9 pagesFinal Project IN Philo: Richmond Lance C. AguasRmNo ratings yet

- Property HarvardDocument27 pagesProperty HarvardPriyansh JainNo ratings yet

- How Power Corrupts : Political PartiesDocument12 pagesHow Power Corrupts : Political PartiesOana Camelia SerbanNo ratings yet

- Nature and Human Dignity: Customs (Kant, 1785), When He Sustains That The Human Being Has No Value Without Dignity, WhichDocument21 pagesNature and Human Dignity: Customs (Kant, 1785), When He Sustains That The Human Being Has No Value Without Dignity, WhichFrancis Robles SalcedoNo ratings yet

- JPU 5 Legal Positivism IntroDocument7 pagesJPU 5 Legal Positivism IntroAriane OngNo ratings yet

- Definition & Concept of PropertyDocument9 pagesDefinition & Concept of PropertyDhaval GohelNo ratings yet

- Property Law (Best)Document59 pagesProperty Law (Best)mohanegasaNo ratings yet

- Cohen Vs NozickDocument20 pagesCohen Vs NozickalejandroatlovNo ratings yet

- What Is Man?: Three Interpretations of ManDocument15 pagesWhat Is Man?: Three Interpretations of ManstriswidiastutyNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence ProjectDocument24 pagesJurisprudence ProjectAnubhutiVarma100% (1)

- By Friedrich Nietzsche: The Gay ScienceDocument10 pagesBy Friedrich Nietzsche: The Gay ScienceKaustav BoseNo ratings yet

- Legal Theory 2ND PROJECT PDF - 4 4Document1 pageLegal Theory 2ND PROJECT PDF - 4 4SabaNo ratings yet

- Property and Free Initiative in EconomyDocument9 pagesProperty and Free Initiative in EconomyFlavio HeringerNo ratings yet

- 3359short Answer Responses To The Good Life QuestionsDocument4 pages3359short Answer Responses To The Good Life QuestionsVanessa BateupNo ratings yet

- Example: Athens Too, Cradle of Western Democracy, Did Not Have The Concept of A RightDocument7 pagesExample: Athens Too, Cradle of Western Democracy, Did Not Have The Concept of A RightChandan KumarNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Project Topic - Possession and OwnershipDocument17 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: Project Topic - Possession and OwnershipSarang ShekharNo ratings yet

- Conclusion: 5.1 Revisiting Deep EcologyDocument39 pagesConclusion: 5.1 Revisiting Deep EcologySRIKANTA MONDALNo ratings yet

- Property Chapter 1Document17 pagesProperty Chapter 1Beenyaa BadhaasaaNo ratings yet

- JPU 5 Legal Positivism, IntroDocument6 pagesJPU 5 Legal Positivism, IntroЁнатхан РаагасNo ratings yet

- Materialism and ConsumerismDocument28 pagesMaterialism and ConsumerismdocfairyNo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter UCSPDocument9 pages1st Quarter UCSPAr Anne Ugot100% (1)

- Ownership in IslamDocument36 pagesOwnership in IslamBharosa KaemNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Theories of IPR and Its Jurisprudential Aspects: ObjectivesDocument22 pagesUnit 3 Theories of IPR and Its Jurisprudential Aspects: ObjectivesArya MittalNo ratings yet

- Vida Animal Valor Intrínseco?Document13 pagesVida Animal Valor Intrínseco?Jorge Eliecer Sierra MerchanNo ratings yet

- JPU 2 Person & LawDocument7 pagesJPU 2 Person & LawЁнатхан РаагасNo ratings yet

- Intro To Philo PointersDocument5 pagesIntro To Philo PointersAlloiza CaguiclaNo ratings yet

- The Rights of AnimasDocument3 pagesThe Rights of AnimasjonygringoNo ratings yet

- Property JurisDocument11 pagesProperty JurisMahek RathodNo ratings yet

- CEM Joad DecadenceDocument435 pagesCEM Joad DecadenceIan TangNo ratings yet

- Human NatureDocument14 pagesHuman NatureRick LeBrasseurNo ratings yet

- The CrowdDocument94 pagesThe Crowd村上杂記Murakami NotesNo ratings yet

- Germain Grisez - A Contemporary Natural-Law Ethics. 1989 Marquette University Press.Document20 pagesGermain Grisez - A Contemporary Natural-Law Ethics. 1989 Marquette University Press.filosoph100% (1)

- Oderberg - The Illusion of Animal RightsDocument9 pagesOderberg - The Illusion of Animal RightsfrecyclNo ratings yet

- The Treatise On Greed and The Qualities of An Exemplary StatesmanDocument18 pagesThe Treatise On Greed and The Qualities of An Exemplary StatesmanDivinekid082No ratings yet

- Katherine Tingley, Editor Vol. Xiv No. April: THE MostDocument71 pagesKatherine Tingley, Editor Vol. Xiv No. April: THE MostOcultura BRNo ratings yet

- Orlando Patterson Trafficking Gender SlaveryDocument30 pagesOrlando Patterson Trafficking Gender SlaverySara-Maria SorentinoNo ratings yet

- Honore, Property, Title and RetributionDocument9 pagesHonore, Property, Title and RetributionFernandoAtria100% (1)

- Wealth of NationsDocument3 pagesWealth of Nationsbloodberry1017No ratings yet

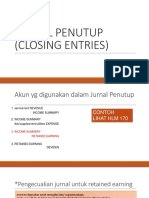

- Jurnal Penutup (Closing Entries)Document9 pagesJurnal Penutup (Closing Entries)apelina teresiaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Harmony in The SocietyDocument47 pagesUnderstanding Harmony in The Societykanmani100% (2)

- Adam SmithDocument3 pagesAdam SmithAmanKumarNo ratings yet

- Identifying Affluent Tehsils in Rural India Approach To The ProjectDocument76 pagesIdentifying Affluent Tehsils in Rural India Approach To The ProjectGaneshRathodNo ratings yet

- CheckstubsDocument5 pagesCheckstubsAaron ThompsonNo ratings yet

- Victorian Women in The Middle-Class EssayDocument5 pagesVictorian Women in The Middle-Class Essayapi-249308850No ratings yet

- Oliver Wyman - How To Catch US Mass Affluent CustomersDocument19 pagesOliver Wyman - How To Catch US Mass Affluent CustomersmajkasklodowskaNo ratings yet

- Network 18Document44 pagesNetwork 18Ashok ThakurNo ratings yet

- 16 Rich HabitsDocument16 pages16 Rich HabitsJosué GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts in Economics (Notes)Document7 pagesBasic Concepts in Economics (Notes)149 Reehab ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Sokoloff - 2000 - Institutions, Factor Endowments, and Paths of Development in The New WorldDocument34 pagesSokoloff - 2000 - Institutions, Factor Endowments, and Paths of Development in The New Worldyezuh077No ratings yet

- Di Boscio - Mining Enterprises and Regional Economic DevelopmentDocument316 pagesDi Boscio - Mining Enterprises and Regional Economic DevelopmentstriiderNo ratings yet

- SubtitleDocument4 pagesSubtitleTawfiq BA ABBADNo ratings yet

- Please DocuSign MAF J-Business Docusign VersDocument13 pagesPlease DocuSign MAF J-Business Docusign VersCh tahaNo ratings yet

- HOBA Special ProbDocument19 pagesHOBA Special ProbRujean Salar AltejarNo ratings yet

- Cariday V CADocument7 pagesCariday V CAmaria100% (1)

- Impact of Financial Literacy Program On Financial Behaviour A Case Study of Selected Nurses From Public Hospitals in GhanaDocument9 pagesImpact of Financial Literacy Program On Financial Behaviour A Case Study of Selected Nurses From Public Hospitals in GhanaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Women in Water UtilitiesDocument92 pagesWomen in Water UtilitiessofiabloemNo ratings yet

- Rich Dad Poor DadDocument11 pagesRich Dad Poor Dadsalim_sajidNo ratings yet

- Madhya PradeshDocument34 pagesMadhya PradeshAditya AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Individualization of Robo-AdviceDocument8 pagesIndividualization of Robo-AdviceDaniel Lee Eisenberg JacobsNo ratings yet

- Pathfinder - Basic Economics of DD v0.1Document10 pagesPathfinder - Basic Economics of DD v0.1S. BalcrickNo ratings yet

- 8.1 9 Ujamaa PDFDocument19 pages8.1 9 Ujamaa PDFEgqfaxaf100% (1)

- Struck BookDocument270 pagesStruck BookRestee Mar Rabino Miranda100% (2)

- National Income Accounting AbelDocument12 pagesNational Income Accounting AbelKushagra AroraNo ratings yet

- Fabm2 m4 de Guzman Keir Eduard S.. Abm Dah 1Document2 pagesFabm2 m4 de Guzman Keir Eduard S.. Abm Dah 1charles harvey ablitasNo ratings yet

- Berle - For Whom Corporate Managers ARE Trustees - A NoteDocument9 pagesBerle - For Whom Corporate Managers ARE Trustees - A NotePleshakov AndreyNo ratings yet

- Stop Acting Rich SummaryDocument6 pagesStop Acting Rich Summary187190No ratings yet