Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious Puberty

A Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious Puberty

Uploaded by

Abdurrahman HasanuddinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious Puberty

A Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious Puberty

Uploaded by

Abdurrahman HasanuddinCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Pediatrics

http://cpj.sagepub.com/

A Pediatrician's Guide to Central Precocious Puberty

Gad B. Kletter, Karen O. Klein and Yolanda Y. Wong

CLIN PEDIATR published online 14 July 2014

DOI: 10.1177/0009922814541807

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://cpj.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/07/11/0009922814541807

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Clinical Pediatrics can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://cpj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://cpj.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Jul 14, 2014

What is This?

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

541807

research-article2014

CPJXXX10.1177/0009922814541807Clinical PediatricsKletter et al

Commentary

Clinical Pediatrics

A Pediatrician’s Guide to Central 1–11

© The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permissions:

Precocious Puberty sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0009922814541807

cpj.sagepub.com

Gad B. Kletter, MD1, Karen O. Klein, MD2,

and Yolanda Y. Wong, MD3

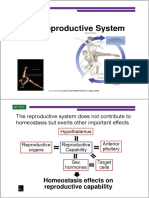

Introduction Epidemiology

On the frontline of child and adolescent care, pediatri- The epidemiology of CPP is somewhat nebulous, with a

cians are uniquely suited to assess signs of puberty that commonly cited prevalence range of 1 in 5000 to 1 in

may signal abnormal developmental processes or 10 000 children.6 CPP is known to occur more frequently

underlying pathology. A working knowledge of preco- in girls than in boys and has different predominant

cious puberty diagnosis and management is, therefore, causes for each sex. Idiopathic CPP, without an identifi-

invaluable for these clinicians. Referral of children for able predisposing condition, accounts for the majority of

the evaluation of precocious puberty is becoming an cases of precocious puberty in girls, but is less frequent

increasingly common phenomenon in pediatric endo- in boys.1,5,7 Central nervous system findings such as

crinologists’ offices.1 Although many referrals result in tumors and congenital malformations are more fre-

reassurance that the patient is within the normal spec- quently observed in boys who present with precocious

trum of development or is experiencing benign pubertal puberty.4,5,7 It is estimated that two thirds of precocious

variants, early identification and treatment is critical puberty cases in boys are due to neurological abnormali-

when true precocious puberty is present.1,2 The need for ties.4 The likelihood of an organic cause for CPP is

timely attention to apparent premature development is greater in patients who present at younger ages.5,6

augmented by the possibility that precocious puberty is Familial forms of CPP have been reported, but little

the result of a tumor or other disorder. is known about the pervasiveness of this condition or its

Precocious puberty is defined as the onset of devel- underlying genetic mechanisms.8 As pediatricians are

opmental signs of sexual maturation earlier than would caring for more and more children adopted from devel-

be expected based on population norms. This is typi- oping countries, it is also important to be aware of the

cally delineated as puberty onset before 8 years in girls greater prevalence of precocious puberty among nation-

and 9 years in boys. In its most common form, central ally or internationally adopted children.9-13 The reasons

precocious puberty (CPP), sexual maturation proceeds for this phenomenon are not well understood but are

from a premature activation of the hypothalamic–pitu- thought to be related to racial, emotional, or environ-

itary–gonadal (HPG) axis.3 The HPG axis is active dur- mental factors such as improved nutrition or previous

ing infancy, dormant during childhood, and reactivated exposure to endocrine disruptors. The various etiologies

at the onset of puberty. Activation of the reproductive and underlying conditions associated with CPP are pre-

axis is defined by a pulsatile expression of gonadotro- sented in Table 1.

pin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This, in turn, activates

the pituitary to release the gonadotropin hormones

Signs and Variants

(luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle-stimulating hor-

mone [FSH]). Because gonadotropin hormones are the The clinical signs of CPP are consistent with expected

driving force for pubertal changes in CPP, the condition changes occurring during puberty, including the following:

is also referred to as gonadotropin-dependent preco-

cious puberty. Peripheral precocious puberty, on the 1

Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

other hand, is the premature sexual maturation that 2

Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA, USA

arises from aberrant secretion of sex steroids indepen- 3

Mid-City Community Clinic, San Diego, CA, USA

dent of gonadotropin production.4 Although it does not

Corresponding Author:

require HPG axis activation, the presence of peripheral Gad B. Kletter, MD, 7102 153rd Ave NE, Redmond, WA 98052,

precocious puberty can induce HPG axis activation, USA.

resulting in CPP.5 Email: gadklett@gmail.com

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

2 Clinical Pediatrics

Table 1. Central Precocious Puberty Etiologya.

Category Underlying Disease/Condition

Idiopathic Sporadic

CNS abnormalities Hypothalamic hamartoma

Tumors Astrocytoma, craniopharingeoma, ependymoma, optical or hypothalamic

glioma, LH-secreting adenoma, pinealoma, neurofibroma, dysgerminoma

Congenital malformations Arachnoid cyst, suprasellar cyst, hydrocephaly, spina bifida, septum-

optical dysplasia, myelomeningocele, ectopic neurohypophysis, vascular

malformations

Acquired disease/lesion Encephalitis, meningitis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis granulomas, abscesses

Induced by medical procedures or injury Cranial irradiation, chemotherapy, head trauma, perinatal asphyxia, CNS

surgery

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; LH, luteinizing hormone.

a

Adapted from Brito et al (2008)4 and Carel and Leger (2008).5

•• Increased growth velocity isolated events may be forerunners of true precocious

•• Pubic and axillary hair appearance puberty or may be self-limiting, even regressing. The

•• Acne/oily skin likelihood of encountering these variants in clinical prac-

•• Changes in musculature tice is greater than that of CPP. In a cohort of US children

•• Body odor referred for evaluation of early puberty, 46% were diag-

•• Increased appetite nosed with premature adrenarche, 18% with premature

•• Breast or genital development thelarche, and 9% with true precocious puberty.2

Moreover, only half of those with precocious puberty

In girls, CPP often initially presents as increased growth had progressive disease that required treatment.

velocity or breast development (thelarche), which may Isolated premature thelarche refers to breast develop-

occur in isolation or associated with other physical ment in the absence of other clinical signs of puberty or

changes, such as increased uterine volume and pubic estrogen secretion.4 The onset of isolated premature the-

hair development (pubarche).4,14 The initial indicator of larche is generally within the first 3 years of life and

CPP in boys is typically an increase in testicular volume may continue through puberty or regress over time. In a

or length.4 However, the appearance of these pubertal recent study of an unselected population of girls in the

characteristics in a girl younger than 8 years or a boy United States aged 12 to 48 months, premature thelarche

younger than 9 years does not immediately signal CPP was present in 15 of 318 (4.7%) children.21 At the time

because there are many variants of early puberty. of follow-up (6 months or more after the initial visit),

In some cases, precocious puberty progresses at a breast development was still evident in just 44% of

slow pace or does not advance. This type of puberty cases. There does not appear to be adverse sequelae

variant has been described as benign or slowly pro- associated with isolated premature thelarche; bone age

gressing; affected patients have a favorable height and growth velocity are generally unaffected.4,22 When

prognosis and are thus unlikely to require treatment.15,16 thelarche is the lone sign of puberty onset and is not fol-

In fact, treatment with GnRH analogs, the standard of lowed by progress in other secondary sexual character-

care for CPP, has not been shown to substantively istics, the condition is considered a natural pubertal

increase adult height attainment in girls with slowly variant that does not require further treatment23; how-

progressive idiopathic CPP.16 Table 2 shows the array of ever, routine follow-up with measurement of gonadotro-

clinical, physical, and hormonal characteristics that are pin and estradiol levels, growth velocity, and bone age is

possible differentiators between rapid and slowly pro- suggested. Pelvic ultrasonography may prove useful at

gressive variants in girls. In general, the rate of progres- early stages to distinguish between the isolated and pro-

sion of physical findings and the rate of progression of gressive forms of thelarche.4

bone maturation are the main distinguishing factors.5,17 Premature pubarche is a common manifestation of

Monitoring for continued evidence of advancing adrenarche (a pubertal stage marked by increased adre-

puberty is currently the most valuable tool available to nal androgen secretion) and is, therefore, alternately

clinicians. referred to as premature adrenarche in the scientific and

There are several forms of premature development in clinical literature. Affected children may demonstrate

which only a single aspect of puberty is apparent. These some evidence of increased growth velocity or advanced

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

Kletter et al 3

Table 2. Criteria for Differentiating Progressive From Nonprogressive Forms of Precocious Puberty in Girlsa,b.

Criterion Progressive Central Precocious Puberty Nonprogressive Precocious Puberty

Clinical

Progression through pubertal Progression from one stage to the next in Stabilization or regression of pubertal

stages 3 to 6 months signs or progression from one stage to

the next over at least a year

Growth velocity Accelerated (in excess of 6 cm per year) Usually normal for age

Bone age Usually advancing by more than 1 year Not accelerating in degree of advance

per year

Predicted adult height Below target height range or declining on Within target height range

serial determinations

Uterine development

Pelvic ultrasonography scanc Uterine volume >2.0 mL or length >34 Uterine volume ≤2.0 mL or length ≤34

mm; pear-shaped uterus, endometrial mm; prepubertal, tubular-shaped uterus

thickening (endometrial echo)

Hormone levels

Estradiol Usually measurable estradiol level with Estradiol not detectable or close to the

advancing pubertal development detection limit

LH peak after GnRH or GnRH In the pubertal range In the prepubertal range

agonist testd

Abbreviations: LH, luteinizing hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

a

These criteria were developed to distinguish progressive CPP (characterized by a sustained activation of the gonadotropic axis) from

nonprogressive precocious puberty (in which the gonadotropic axis is not activated) and were obtained in cross-sectional and small

longitudinal studies; their reliability has not been fully evaluated.18-20

b

Reprinted with permission from Carel and Leger (2008).5

c

Pelvic ultrasonography is used much more frequently in Europe than in the United States. Uterine development reflects sustained exposure to

estrogens and is a marker of progressive puberty.

d

GnRH is not available in the United States for use in testing.

bone age as well as the appearance of axillary hair, body considered among normal puberty variants; affected chil-

odor, and acne.4 Pubarche and advanced growth veloc- dren should be evaluated for possible ovarian or uterine

ity/bone age without evidence of breast development in pathology.23

girls or in conjunction with a prepubertal testicular vol-

ume in boys may indicate an adrenal disorder or andro-

Diagnosis

gen exposure.5,23 Putative risk factors for premature

pubarche include children who were born prematurely, The first step in the diagnosis of precocious puberty is to

children who were small for their gestational age, and obtain a detailed family and personal history. Special

children who are overweight or obese.24,25 Overt puberty attention should be given to the following:

in children with premature pubarche generally begins

early but within the normal range for the general popula- •• Order and timing of secondary sex characteristic

tion; adult height is not compromised.25,26 However, pre- appearance

mature adrenarche can be the first sign of precocious •• Age of puberty onset in parents and siblings

puberty and has been linked to an increased risk for •• Neurologic signs and symptoms

patients to develop polycystic ovary syndrome and/or •• Past exposure to estrogen, androgen, or mimetic

characteristics of metabolic syndrome, including obe- compounds (including over-the-counter products

sity and type 2 diabetes mellitus.26 such as lavender and tea tree oils27)

Isolated premature menarche is defined as vaginal

bleeding occurring prior to age 8 and without accompany- The growth chart can determine the patient’s pace of

ing signs of puberty. There may or may not be elevation in growth, comparing the height and weight velocity

gonadotropin or estradiol levels.4 Girls presenting with against standard growth curves. If past data are not

premature menarche should be assessed via physical available, growth velocity will need to be monitored

examination and medical history to eliminate the possibil- prospectively for 3 to 6 months or more.23 Most girls

ity that vaginal bleeding was caused by genital injury, for- with CPP track above the 75th percentile in growth

eign body, or manipulation. Premature menarche is not velocity. Because boys have their growth spurt later,

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

4 Clinical Pediatrics

advanced growth velocity is not necessarily detected at Observation of basal elevations in LH by sensitive

early stages of CPP. assays may be sufficient to diagnose CPP without the

Physical examination should include assessment of need for GnRH challenge4,32,33; however, LH response

Tanner staging and signs of puberty. Early signs of pre- to GnRH is the “gold standard” for CPP evaluation. The

cocious puberty may be subtle, particularly in girls. GnRH stimulation test is performed by administering

Staging of breast development is particularly challeng- exogenous GnRH or a GnRH analog and obtaining

ing in overweight or obese girls28; careful palpation can blood samples at baseline and at regular intervals there-

help distinguish glandular breast tissue from adipose after. Peak serum LH values above a certain assay-spe-

tissue, which is softer and more diffuse compared with cific threshold signify CPP.

a true breast bud. Genital development staging in boys Morning plasma testosterone levels in the pubertal

can be determined visually, but this method is subject to range are indicative of precocious puberty in boys but

a higher degree of interrater variability compared with are not present in all cases.4,5 Similarly, low levels of

objective measure of testicular volume using an orchi- estradiol do not rule out a CPP diagnosis because many

dometer.29 If an orchidometer is not available, testicular girls with precocious puberty have estradiol levels in the

volume can be estimated using the formula 0.71 × prepubertal range.4 Excessively high estradiol levels

length × width × height.30 Testicular volume >4 mL (>100 pg/mL) may be concerning as a potential indica-

(roughly larger than a black olive) or length of >2.5 cm tor of ovarian cysts or tumors.5 The evaluation of other

is indicative of pubertal development, except in boys hormone levels will depend on the clinical case at hand.

younger than 2 years for whom testicular volume may For example, thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroxin

not have appreciably increased despite the onset of pre- levels should be measured if hypothyroidism is sus-

cocious puberty.4 Testicular size may also remain pre- pected. In boys with early signs of puberty accompanied

pubertal in boys with adrenal disorders, premature by advanced growth velocity and bone age but a prepu-

pubarche, or peripheral precocious puberty caused by bertal testicular volume, concentrations of adrenal ste-

conditions other than testicular disorders.5 Testicular roid precursors (particularly 17-hydroxyprogesterone)

ultrasonography is recommended in cases of asymmet- should be measured.

ric testicular size or when peripheral precocious puberty For all hormonal measurements, it is important to use

is suspected. sensitive assays that have been validated in a pediatric

When the above signs point to precocious puberty, population. Also, as there is natural variation in hor-

the next step in diagnosis and follow-up would be to mone levels during childhood, reference standards

obtain a radiograph of the left hand to determine bone should be specific to the age of the patient in question.

age. In patients with CPP, bone age is advanced relative Consultation with a local endocrinologist may be help-

to chronological age. Bone age greater than 2 standard ful in guiding laboratory and assay selection. As of this

deviations above the normal range for a child’s chrono- writing, there are 2 primary pediatric endocrine com-

logical age is characteristic of rapidly progressing pre- mercial laboratories: Esoterix (Austin, TX), a subsidiary

cocious puberty.31 The degree of bone maturation may of Labcorp (Burlington, NC), and Nichols Institute (San

be less pronounced if precocious puberty is detected Juan Capistrano, CA), now owned by Quest Diagnostics

early (ie, not much time passed since onset of puberty (Madison, NJ).

and, therefore, the bone age is not yet advanced). If a Use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the

slow progressing variant of CPP is suspected, repeated head for the identification of central nervous system

bone age assessment before initiation of therapy may be lesions in boys and girls younger than 6 years presenting

warranted, as these patients typically achieve normal with CPP is a generally accepted principle.34 For girls

adult height without treatment.31 Notably, all methods of aged 6 to 8 years, universal application of head MRI is

assessment have bias, and thus, bone age X-ray reading debatable; critics cite a low risk of unsuspected intracra-

remains an inaccurate tool at best.3 nial pathology in this population. However, a recent sys-

Once a bone age has been obtained, it can be used to tematic evaluation of MRI results in girls with CPP

estimate a patient’s predicted adult height. By compar- reported that pathological findings on MRI were not

ing the predicted adult height with the target height cal- uncommon in girls aged 6 years and older.35 That study’s

culated from parent’s height measurements,18 the investigators concluded that head MRI should continue

magnitude of loss in height potential can be evaluated. to be conducted as part of the assessment for girls pre-

Measurement of hormone levels helps in the differ- senting with CPP who are aged younger than 8 years.

ential diagnosis of precocious puberty (Figures 1 and 2). Given that intracranial pathology is more common in

Initial workup in the outpatient pediatrician’s office boys than in girls, MRI is warranted in all boys present-

should include assessment of basal LH and FSH levels. ing with CPP.

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

Kletter et al 5

Figure 1. Differential diagnosis of precocious puberty in girls.

Abbreviations: GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; E2, estradiol; CPP, central

precocious puberty; CNS, central nervous system.

Adapted from Sultan et al (2012)22 and Berberoğlu (2009).23

The majority of preliminary patient evaluations are her chronological age. The patient’s predicted height is

within the purview of the pediatrician (Figure 3). consistent with that of her mother. What would be the

Whether advanced assessments (eg, bone age measure- next step for evaluating this patient?

ment, pelvic or testicular ultrasonography, etc) are per- This patient demonstrates characteristics consistent

formed by the pediatrician depends on the comfort level with premature pubertal development, including early

of the clinician. Referral to a pediatric endocrinologist stages of breast and pubic hair development and bone

for diagnostic evaluation and initiation of therapy is rec- age advancement; however, the lack of overt impact on

ommended when the clinician feels the evidence is con- predicted height and modest sexual maturation may

sistent with precocious puberty or if there is diagnostic indicate a normal pubertal variant. A propensity for ear-

uncertainty. As early treatment yields the best outcomes, lier puberty onset in African American girls compared

timely referral is essential. with other racial/ethnic groups also bears consideration

in this case.36,37 The patient should be monitored closely

by the clinician and her parents for evidence of further

Case Studies pubertal development, with repeat examination includ-

Case 1. A 6-year-old African American girl presents ing bone age assessment in 6 months.

with breast buds and sparse transitional pubic hair. She

is at the 95% percentile for height; bone age measure- Case 2. A 7-year-old Caucasian girl presents with stage

ment reveals an advancement of 18 months relative to 3 breast and pubic hair development. She is currently at

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

6 Clinical Pediatrics

Figure 2. Differential diagnosis of precocious puberty in boys.

Abbreviations: hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; LH, luteinizing hormone; T, testosterone; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; 17

OHP, 17-hydroxyprogesterone; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist; CPP, central precocious puberty; MRI, magnetic resonance

imaging; PP, precocious puberty; CAH, congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Adapted from Carel and Leger (2008)5 and Berberoğlu (2009).23

the 50% percentile for height, but was at the 25% per- development are prepubertal. Bone age is slightly

centile 1 year ago. Both parents are in the 25% percen- advanced relative to the child’s chronological age. What

tile range for height. The patient’s bone age is advanced would be the next step for evaluating this patient?

by 2 years relative to her chronological age. What would In this case, the clinical presentation is consistent

be the next step for evaluating this patient? with either CPP or premature adrenarche. As an

The degree of pubertal development and obvious adopted child, the chances of a precocious puberty

signs of both growth acceleration and bone age advance- finding are elevated relative to the general popula-

ment are indicative of precocious puberty. This patient tion.11,12 Nonetheless, careful attention should be paid

should be referred to a pediatric endocrinologist for fur- to possible sources of previous or current androgen

ther evaluation. exposure. Elevated body weight is another risk factor

for early puberty onset that should be taken in account

Case 3. At an annual well-child visit, the adoptive par- for this case.28,38 In addition to close monitoring for

ents of a 6-year-old girl report a rapid rate of growth and signs of continued pubertal development, the clinician

the presence of body odor but no other visible signs of should discuss with the patient’s family the potential

puberty. Physical examination reveals that the child has impact of excess weight on puberty onset and give

an above normal body mass index, but Tanner stages of guidance on weight management strategies.

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

Kletter et al 7

Figure 3. Diagnostic assessments in children with suspected precocious puberty.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CNS, central nervous system; GnRHa, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog.

Treatment implant remains for 12 months before removal. Other

depot preparations are administered as intramuscular

One of the driving forces for treating CPP is to promote injections monthly or every 3 months.

satisfactory adult height gains in patients with the dis- The 2009 consensus statement on the use of GnRH

ease. Historical data from untreated patients with preco- analogs in children states that the best outcomes with

cious puberty indicate a height loss of approximately 20 GnRH analog therapy in terms of height gains for girls

cm (7.9 in.) for boys and 10 cm (3.9 in.) for girls.15 The are achieved when progressive CPP onset is apparent

potential psychosocial consequences of developing before age 6 years.34 For those girls who present at age 6

ahead of one’s peers are also a consideration when deter- years or older, the decision to initiate treatment depends

mining whether to suspend pubertal development. Early on each individual case. It is recommended that all boys

maturation, even within the normal spectrum of develop- with progressive CPP and compromised adult height

mental timing, heightens social anxiety among girls.39 In potential receive treatment. As mentioned previously,

both girls and boys, earlier puberty onset is associated patients with slow progressive forms of CPP may not

with increased likelihood to engage in sexual risk taking, require treatment. Consequently, before initiating ther-

substance abuse, and antisocial behavior.40,41 A concern apy, a period of follow-up is advisable to ensure that the

that has more recently emerged is the putative link observed precocious puberty is progressive.

between early menarche or male puberty and gyneco- Pubertal development resumes after discontinuation

logical, breast, or testicular cancer.26,42 of GnRH analog therapy.34 No adverse effects on repro-

The standard of care for suppression of pubertal ductive development or fertility have been found to be

development in patients with progressive CPP is GnRH associated with GnRH agonist therapy for the treatment

analog therapy.34 GnRH analogs mask the pulsatile of CPP. Potential concerns, including enduring effects

endogenous GnRH release, which thereby causes a on bone mineral density, increases in body mass index,

decrease in LH and FSH synthesis. There are several and elevated risk for polycystic ovary syndrome, appear

GnRH analogs available in the United States, which dif- to be unfounded.

fer in terms of duration of action, dosing schedule, and Whether or not they receive treatment, patients with

route of administration (Table 3). All of the available CPP require routine monitoring to detect signs of puber-

agents have proven efficacious for HPG axis suppres- tal progression. Growth velocity and bone age should be

sion, yet long-acting formulations are generally pre- evaluated every 6 months. Continued advancement of

ferred to short-acting formulations because of the CPP despite therapy may indicate an issue with treatment

potential for improved patient compliance.34 One of the compliance. Pediatricians and endocrinologists should

more recent developments among the long-acting for- work in concert to ensure that the patient is monitored

mulations is the once-yearly subcutaneous histrelin ace- both in the clinic and at home. An established relation-

tate implant. This thin, flexible tube is placed under the ship and regular contact between families and pediatri-

skin in the upper arm via a small incision, where the cians opens the lines of communication, allowing the

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

8 Clinical Pediatrics

Table 3. Characteristics of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Analogs Available in the United States That Are Used

in the Treatment of Central Precocious Pubertya.

Rapid Acting Monthly Depot 3-Month Depot 12-Month Implant

Agent Nafarelin Leuprolide Leuprolide Histrelin

Brand nameb Synarel Lupron depot-PED-1 Lupron depot-PED-3 Supprelin LA

month month

Dosing 3-4 times daily (intranasal) or Every 28 days Every 90 days Every year

once daily (subcutaneous)

Peak serum 10-45 minutes 4 hours 4-8 hours 1 month

concentrations

Onset of 2-4 weeks 1 month 1 month 1 month

therapeutic

suppression

Advantage Quick onset/offset of effect Dosing and efficacyFewer injections and No injections needed;

well studied fewer compliance noncompliance potentially

concerns less concerning

Disadvantage Multiple daily doses needed; Painful injections; Painful injection Requires a minor surgical

requires compliance with requires compliance procedure for insertion

daily administration with monthly and removal, which may

injections require general anesthesia

Side effects and Generally reserved for patients Pain, erythema, inflammatory reactions, and Implant site reactions,

cautions with sterile abscesses from sterile abscesses at the injection site potential scarring

depot injections

a

Adapted from Carel and Leger (2008)5 and Carel et al (2009).34

b

Synarel is manufactured by G. D. Searle LLC, New York, NY.19 Lupron depot-PED-1 month and Lupron depot-PED-3 month are

manufactured by AbbVie Inc, North Chicago, IL.20 Supprelin LA is manufactured by Endo Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Malvern, PA.43

pediatrician to address concerns and educate parents extreme emotional distress for the patient or family.36

regarding changes to be aware of in their child. Parental This guidance is controversial and has the potential to

vigilance in observing and reporting signs of further overlook patients who could benefit from therapeutic

pubertal development should be encouraged. intervention. Pediatric endocrinologists in the United

States have, by and large, held with the traditional rec-

ommendations for evaluating precocious puberty when

Clinical Insights signs present before age 8 in girls and age 9 in boys.5

In contemporary clinical practice, multiple factors can Early sexual maturation and/or the diagnosis of pre-

make it challenging to delineate CPP from early normal cocious puberty can be a scary proposition for parents

puberty variants. There appears to be a population-wide and children alike. From the perspective of the pediatri-

decrease in the age of puberty onset, in addition to some cian, this is a teachable moment to address gaps in

underlying racial/ethnic differences in puberty chronol- knowledge, misconceptions, or concerns the family may

ogy.37,38 Speculation abounds as to the root of large- have regarding puberty. Lay perceptions of what consti-

scale changes in puberty onset, with suspected factors tutes “normal” development may not be consistent with

including the obesity epidemic that plagues many medical precepts and are subject to cultural and family

Western nations and possible environmental exposure to influences. Pediatricians are in a position to reassure

endocrine disrupters, particularly in developing coun- parents that although puberty onset occurs at an average

tries.9,28,38 Based on epidemiologic data available at the age of 10.5 years for girls and 11.5 years for boys, it can

time, in 1999, the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine range from 8 to 13 years for girls and 9 to 14 years for

Society published a statement recommending that the boys. Menarche, which occurs on average at age 12.5

age limits for evaluating precocious puberty in girls pre- years, is a common subject of anxiety for parents.

senting with breast development or pubic hair be pushed Parents are often concerned that growth will stop at the

back to before age 7 in white girls and age 6 in African time of menarche, when, in reality, girls will continue to

American girls. Exceptions to this would include cases grow an average of 2 additional inches. Parents also

of unusually rapid progression, the presence of neuro- worry that menarche will follow rapidly after breast

logic pathology, or when puberty progression causes development, yet there is generally a 2-year delay

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

Kletter et al 9

between these developmental milestones (although this •• How to talk to their child about the condition

may be foreshortened in patients with CPP). The physi- •• What to tell friends and relatives

cal examination conducted before a child’s entry into •• The effect of precocious puberty on their child

kindergarten would be an important opportunity for this •• How tall will their child be

type of discussion with parents. By the time children •• Long-term risks of treatment

reach school age, they require less supervision in dress- •• Fear that the child is not mentally prepared to

ing and bathing, which may result in parents being handle menses or will lose her innocence and

unaware of physical changes already taking place unless become more like a teenager

they are attentive to indicators of early development. •• Types of child and family support that are

Early dialogue about puberty may also allow pediatri- available

cians to combat the perception that the increased height

or physical changes associated with precocious puberty Where there are issues of poor acculturation or health

are good, rather than worrisome—a belief that causes literacy within the family, information from reliable

some parents to feel disinterested in further evaluation external sources can be limited. Providing accurate, eas-

and follow-up for their child. ily understood, and culturally appropriate education is

Time should also be spent assessing how a child per- important in allaying parental fears and helping children

ceives his or her development, especially in reference to adapt to the physical and emotional changes they are

their peers and what they hear from family members. experiencing.

Along with the physical aspects of puberty, it is impor-

tant to assess for the emotional implications of early

puberty. Children who appear older may oftentimes be

Conclusions

pressured by their family or social circles to act more CPP is a manageable disease for which there are effective

mature than their age. The pediatrician has the opportu- treatment options when the condition is identified early

nity to address issues regarding a child’s self-image, and treated appropriately. As the primary source of health

anxiety or mood changes, sexuality, and peer influences. care provider interaction for children, pediatricians are

Even when findings are reassuring and point to a normal ideally situated to be the first to detect signs of precocious

variant in development, a child still benefits from guid- puberty through direct observation and proactive discus-

ance during this stage in life when social influence and sion with patients and their families. Pediatricians should

peer pressure can be especially challenging and harsh. carefully evaluate growth charts and perform pubertal

It is important to listen to the child’s questions and examinations at all well-child visits. Routine visits also

watch for nonverbal cues, like tears and fear. Even give clinicians occasion to query parents about their

phrases like “Your body is growing up a little too soon” child’s development or if they have observed moodiness,

can make a child feel like something is “wrong” with acne, or other signs of puberty in their child. Physical

them. They need to be told that they are not going to die, clues and diagnostic evaluations create an overall clinical

they did not do anything wrong, and they will have a picture that allows the clinician to distinguish normal

normal life. Parents often ask questions about how to puberty variants from CPP. Prompt referral to a pediatric

talk to their child about sex, masturbation, coping with endocrinologist gives the patient with CPP the best chance

dressing age appropriately, and whether they should to benefit from therapeutic intervention. Ongoing follow-

allow their young child to use deodorant. Some parents up is necessary to monitor the child’s development and

appreciate permission to cut pubic hairs or shave axil- provides further opportunities for the pediatrician to

lary hairs, and even counseling on sports bra options can address psychosocial issues that may arise.

be reassuring. Once a child is on treatment, parental con-

cerns focus on future fertility.44-47 Acknowledgments

Even after having seen the endocrinologist, some The authors thank Oksana Terleckyi, PharmD, of Endo

families and children benefit from ongoing conversa- Pharmaceuticals Inc., for reviewing draft versions of the arti-

tions with their primary care provider to help process cle for scientific accuracy. The authors also thank Crystal

information over time. Common parental questions/con- Murcia, PhD, and Lamara D. Shrode, PhD, CMPP, of The JB

cerns that the pediatrician may need to address include Ashtin Group, Inc, for assistance in preparing this article for

the following: publication based on the authors’ input and direction.

•• Will treatment and follow-up return the patient to Declaration of Conflicting Interests

the prepubertal state or simply stop the progres- The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of

sion of puberty interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

10 Clinical Pediatrics

publication of this article: Gad B. Kletter, MD, has received puberty in 276 girls examined biannually over two years.

grant/research support funding from Eli Lilly and Endo Horm Res. 2009;72:236-246.

Pharmaceuticals Inc, and he has participated in speakers’ 12. Soriano-Guillén L, Corripio R, Labarta JI, et al. Central

bureaus for Pfizer and Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. Karen O. precocious puberty in children living in Spain: incidence,

Klein, MD, has received grant/research support funding from prevalence, and influence of adoption and immigration. J

Abbott and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. She has served as a con- Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4305-4313.

sultant for Abbott and Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc, and has par- 13. Deng F, Tao FB, Liu DY, et al. Effects of growth envi-

ticipated in speakers’ bureaus for Abbott and Endo ronments and two environmental endocrine disruptors

Pharmaceuticals Inc. Yolanda Y. Wong, MD, has declared no on children with idiopathic precocious puberty. Eur J

potential conflicts of interest. Endocrinol. 2012;166:803-809.

14. Prété G, Couto-Silva AC, Trivin C, Brauner R. Idiopathic

Funding central precocious puberty in girls: presentation factors.

BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:27.

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial sup-

15. Carel JC, Lahlou N, Roger M, Chaussain JL. Precocious

port for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

puberty and statural growth. Hum Reprod Update.

article: Funding to support the preparation of this article was

2004;10:135-147.

provided by Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc, Malvern, Pennsylvania.

16. Massart F, Federico G, Harrell JC, Saggese G. Growth

outcome during GnRH agonist treatments for slowly pro-

References gressive central precocious puberty. Neuroendocrinology.

1. Mogensen SS, Aksglaede L, Mouritsen A, et al. Diagnostic 2009;90:307-314.

work-up of 449 consecutive girls who were referred to 17. Calcaterra V, Sampaolo P, Klersy C, et al. Utility of breast

be evaluated for precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol ultrasonography in the diagnostic work-up of precocious

Metab. 2011;96:1393-1401. puberty and proposal of a prognostic index for identifying

2. Kaplowitz P. Clinical characteristics of 104 children girls with rapidly progressive central precocious puberty.

referred for evaluation of precocious puberty. J Clin Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:85-91.

Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3644-3650. 18. Klein KO, Barnes KM, Jones JV, Feuillan PP, Cutler

3. Styne DM, Grumbach MM. Puberty: ontogeny, neuroen- GB Jr. Increased final height in precocious puberty after

docrinology, physiology, and disorders. In: Melmed S, long-term treatment with LHRH agonists: the National

Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Institutes of Health experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: 2001;86:4711-4716.

Saunders; 2011:1054-1201. 19. Synarel [package insert]. New York, NY: G.D. Searle

4. Brito VN, Latronico AC, Arnhold IJ, Mendonça BB. LLC; 2012.

Update on the etiology, diagnosis and therapeutic man- 20. Lupron [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc;

agement of sexual precocity. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2013.

2008;52:18-31. 21. Curfman AL, Reljanovic SM, McNelis KM, et al.

5. Carel JC, Leger J. Clinical practice. Precocious puberty. N Premature thelarche in infants and toddlers: prevalence,

Engl J Med. 2008;358:2366-2377. natural history and environmental determinants. J Pediatr

6. Partsch CJ, Sippell WG. Treatment of central preco- Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:338-341.

cious puberty. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 22. Sultan C, Gaspari L, Kalfa N, Paris F. Clinical expres-

2002;16:165-189. sion of precocious puberty in girls. Endocr Dev. 2012;22:

7. Jakubowska A, Grajewska-Ferens M, Brzewski M, Sopyło 84-100.

B. Usefulness of imaging techniques in the diagnostics of 23. Berberoğlu M. Precocious puberty and normal vari-

precocious puberty in boys. Pol J Radiol. 2011;76:21-27. ant puberty: definition, etiology, diagnosis and current

8. Silveira LFG, Trarbach EB, Latronico AC. Genetics basis management. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2009;1:

for GnRH-dependent pubertal disorders in humans. Mol 164-174.

Cell Endocrinol. 2010;324:30-38. 24. Neville KA, Walker JL. Precocious pubarche is associ-

9. Krstevska-Konstantinova M, Charlier C, Craen M, et ated with SGA, prematurity, weight gain, and obesity.

al. Sexual precocity after immigration from developing Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:258-261.

countries to Belgium: evidence of previous exposure to 25. de Ferran K, Paiva IA, Garcia Ldos S, Gama Mde P,

organochlorine pesticides. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1020- Guimarães MM. Isolated premature pubarche: report

1026. of anthropometric and metabolic profile of a Brazilian

10. Teilmann G, Pedersen CB, Skakkebæk NE, Jensen

cohort of girls. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;75:367-373.

TK. Increased risk of precocious puberty in interna- 26. Golub MS, Collman GW, Foster PM, et al. Public health

tionally adopted children in Denmark. Pediatrics. implications of altered puberty timing. Pediatrics.

2006;118:e391-e399. 2008;121(suppl 3):S218-S230.

11. Teilmann G, Petersen JH, Gormsen M, Damgaard K,

27. Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach KS, Bloch CA. Prepubertal

Skakkebæk NE, Jensen TK. Early puberty in interna- gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J

tionally adopted girls: hormonal and clinical markers of Med. 2007;356:479-485.

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

Kletter et al 11

28. Burt Solorzano CM, McCartney CR. Obesity and the

39. Blumenthal H, Leen-Feldner EW, Babson KA, Gahr JL,

pubertal transition in girls and boys. Reproduction. Trainor CD, Frala JL. Elevated social anxiety among early

2010;140:399-410. maturing girls. Dev Psychol. 2011;47:1133-1140.

29. Sørensen K, Mouritsen A, Aksglaede L, Hagen CP,

40. Downing J, Bellis MA. Early pubertal onset and its rela-

Mogensen SS, Juul A. Recent secular trends in pubertal tionship with sexual risk taking, substance use and anti-

timing: implications for evaluation and diagnosis of pre- social behaviour: a preliminary cross-sectional study.

cocious puberty. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;77:137-145. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:446.

30. Paltiel HJ, Diamond DA, Di Canzio J, Zurakowski D, 41. Copeland W, Shanahan L, Miller S, Costello EJ, Angold

Borer JG, Atala A. Testicular volume: comparison of A, Maughan B. Outcomes of early pubertal timing in

orchidometer and US measurements in dogs. Radiology. young women: a prospective population-based study. Am

2002;222:114-119. J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1218-1225.

31. Martin DD, Wit JM, Hochberg Z, et al. The use of bone 42. Fujita M, Tase T, Kakugawa Y, et al. Smoking, earlier

age in clinical practice—part 2. Horm Res Paediatr. menarche and low parity as independent risk factors for

2011;76:10-16. gynecologic cancers in Japanese: a case-control study.

32. Lee HS, Park HK, Ko JH, Kim YJ, Hwang JS. Utility Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;216:297-307.

of basal luteinizing hormone levels for detecting central 43.

Supprelin [package insert]. Malvern, PA: Endo

precocious puberty in girls. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44: Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2013.

851-854. 44. Feuillan PP, Jones JV, Barnes K, Oerter-Klein K, Cutler

33. Pasternak Y, Friger M, Loewenthal N, Haim A,

GB Jr. Reproductive axis after discontinuation of gonad-

Hershkovitz E. The utility of basal serum LH in prediction otropin-releasing hormone analog treatment of girls with

of central precocious puberty in girls. Eur J Endocrinol. precocious puberty: long term follow-up comparing girls

2012;166:295-299. with hypothalamic hamartoma to those with idiopathic

34. Carel JC, Eugster EA, Rogol A, et al. Consensus state- precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:

ment on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone ana- 44-49.

logs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e752-e762. 45. Heger S, Muller M, Ranke M, et al. Long-term GnRH ago-

35. Mogensen SS, Aksglaede L, Mouritsen A, et al.

nist treatment for female central precocious puberty does

Pathological and incidental findings on brain MRI in a not impair reproductive function. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

single-center study of 229 consecutive girls with early or 2006;254-255:217-220.

precocious puberty. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29829. 46. Heger S, Partsch CJ, Sippell WG. Long-term outcome

36. Kaplowitz PB, Oberfield SE. Reexamination of the age after depot gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treat-

limit for defining when puberty is precocious in girls in ment of central precocious puberty: final height, body

the United States: implications for evaluation and treat- proportions, body composition, bone mineral density,

ment. Drug and Therapeutics and Executive Committees and reproductive function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society. 1999;84:4583-4590.

Pediatrics. 1999;104:936-941. 47. Pasquino AM, Pucarelli I, Accardo F, Demiraj V, Segni

37. Biro FM, Galvez MP, Greenspan LC, et al. Pubertal assess- M, Di Nardo R. Long-term observation of 87 girls

ment method and baseline characteristics in a mixed lon- with idiopathic central precocious puberty treated with

gitudinal study of girls. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e583-e590. gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs: impact on

38. Rosenfield RL, Lipton RB, Drum ML. Thelarche, pubarche, adult height, body mass index, bone mineral content,

and menarche attainment in children with normal and ele- and reproductive function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

vated body mass index. Pediatrics. 2009;123:84-88. 2008;93:190-195.

Downloaded from cpj.sagepub.com at UCSF LIBRARY & CKM on December 9, 2014

You might also like

- DIY HRT Harm Reduction GuideDocument12 pagesDIY HRT Harm Reduction GuideOliver Hall100% (1)

- Activity 2 - The Wheel Keeps On TurningDocument2 pagesActivity 2 - The Wheel Keeps On TurningKiel Angelo Monterey100% (1)

- 2207 1530 Mr. Amir SohailDocument1 page2207 1530 Mr. Amir SohailAwais awanNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Outcome, Second EditionDocument9 pagesNeonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Outcome, Second EditionMatheus HendelNo ratings yet

- Diagnóstico de PC en Niños A TérminoDocument6 pagesDiagnóstico de PC en Niños A TérminoarapontepuNo ratings yet

- Clinical Consensus Statement Pediatric Chronic RhinosinusitisDocument12 pagesClinical Consensus Statement Pediatric Chronic RhinosinusitisThomasMáximoMancinelliRinaldoNo ratings yet

- Biss 2018Document4 pagesBiss 2018Samira tNo ratings yet

- Review Article Update On Precocious Puberty in Girls: Erica A. Eugster MDDocument5 pagesReview Article Update On Precocious Puberty in Girls: Erica A. Eugster MDlenny tri selvianiNo ratings yet

- Hidronefrosisi 1Document12 pagesHidronefrosisi 1Zwinglie SandagNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Oute CoDocument9 pagesNeonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Oute CoAbdi KebedeNo ratings yet

- Identification and Treatment of Retinopathy of Prematurity Update 2017Document9 pagesIdentification and Treatment of Retinopathy of Prematurity Update 2017G VenkateshNo ratings yet

- The Complex Aetiology of Cerebral PalsyDocument16 pagesThe Complex Aetiology of Cerebral PalsyAileen MéndezNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022057010Document23 pagesPeds 2022057010hb75289kyvNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022057010Document24 pagesPeds 2022057010aulia lubisNo ratings yet

- Next-Generation Sequencing Approach in The Diagnosis of Delayed PubertyDocument6 pagesNext-Generation Sequencing Approach in The Diagnosis of Delayed Pubertylenny tri selvianiNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy in Pakistani Children: A Hospital Based SurveyDocument8 pagesCerebral Palsy in Pakistani Children: A Hospital Based Surveyclaimstudent3515No ratings yet

- Avoiding The Sequela Associated With Deformational PlagiocephalyDocument8 pagesAvoiding The Sequela Associated With Deformational PlagiocephalychiaraNo ratings yet

- Apnea Del PrematuroDocument8 pagesApnea Del PrematuroAndres ChasiNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Child With Intellectual Disability: Review ArticleDocument5 pagesInvestigating The Child With Intellectual Disability: Review ArticleCristinaNo ratings yet

- Management of Childhood Onset Nephrotic Syndrome: PediatricsDocument13 pagesManagement of Childhood Onset Nephrotic Syndrome: PediatricssarabisimonaNo ratings yet

- Posterior Fossa Metaanalysis 2016 Part 2Document24 pagesPosterior Fossa Metaanalysis 2016 Part 2SahasraNo ratings yet

- Antecedents of CPDocument8 pagesAntecedents of CPЯковлев АлександрNo ratings yet

- Aetiology and Epidemiology of Cerebral Palsy - Euson (2016)Document6 pagesAetiology and Epidemiology of Cerebral Palsy - Euson (2016)bernice nayeli olivares camposNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy Etiology, Evaluation, and Management of The Most Common Cause For Pediatric DisabilityDocument14 pagesCerebral Palsy Etiology, Evaluation, and Management of The Most Common Cause For Pediatric DisabilityDavid ParraNo ratings yet

- Malingering Case JurnalDocument7 pagesMalingering Case Jurnaldheana claudiaNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Acute Kidney InjuryDocument13 pagesNeonatal Acute Kidney InjuryulfiNo ratings yet

- Important Considerations in The Initial Clinical Evaluation of The Dysmorphic NeonateDocument5 pagesImportant Considerations in The Initial Clinical Evaluation of The Dysmorphic NeonateKaroo_123No ratings yet

- Eight Principles For Patient-Centred and Family-Centred Care For Newborns in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument5 pagesEight Principles For Patient-Centred and Family-Centred Care For Newborns in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitPaola RoigNo ratings yet

- Hydrocephalus ReportDocument8 pagesHydrocephalus ReportMichelle DuNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Non-Immune Hydrops FetailsDocument12 pagesHHS Public Access: Non-Immune Hydrops FetailsYosita AuroraNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Sepsis2Document10 pagesNeonatal Sepsis2riri siahaanNo ratings yet

- Current Update On Recurrent Pregnancy LossDocument6 pagesCurrent Update On Recurrent Pregnancy Losssutomo sutomo100% (1)

- The Newborn Individualized Developmental Care Als 2011 PDFDocument29 pagesThe Newborn Individualized Developmental Care Als 2011 PDFMediCNNo ratings yet

- Antenat Hydronephr-4Document8 pagesAntenat Hydronephr-4Ioannis ValioulisNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Developmental Outcomes in Patients With Deformational PlagiocephalyDocument7 pagesLong-Term Developmental Outcomes in Patients With Deformational PlagiocephalychiaraNo ratings yet

- 1377 FullDocument23 pages1377 FullPutri Wahyuni AllfazmyNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Early Warning SysteDocument14 pagesPaediatric Early Warning SysteTengku rasyidNo ratings yet

- Neral ConsiderationsDocument13 pagesNeral ConsiderationsNga NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Validation of The Postnatal Growth and Retinopathy of Prematurity Screening CriteriaDocument7 pagesValidation of The Postnatal Growth and Retinopathy of Prematurity Screening CriteriaKarthik CNo ratings yet

- Height in Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument3 pagesHeight in Chronic Kidney DiseaseRosi IndahNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Neurodevelopmental Features in Children With Cerebral Palsy and Probable Congenital Zika.Document8 pagesClinical and Neurodevelopmental Features in Children With Cerebral Palsy and Probable Congenital Zika.Ana Clara FreitasNo ratings yet

- Neonatal JaundiceDocument3 pagesNeonatal JaundiceMohola Tebello GriffithNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S000293781502579XDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S000293781502579XsaryindrianyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice Guideline For The Management of Infantile HemangiomasDocument30 pagesClinical Practice Guideline For The Management of Infantile HemangiomasSaya MenarikNo ratings yet

- Catsman Berrevoets2018Document1 pageCatsman Berrevoets2018Ana Corina LopezNo ratings yet

- Two-Step Process For ED UTI Screening in Febrile Young Children: Reducing Catheterization RatesDocument8 pagesTwo-Step Process For ED UTI Screening in Febrile Young Children: Reducing Catheterization RatesJean Pierre RojasNo ratings yet

- Sepsis Mayor 35 AppDocument10 pagesSepsis Mayor 35 AppNatalia CruzNo ratings yet

- Early Identification of Cerebral Palsy Using Neonatal MRI and General Movements Assessment in A Cohort of High-Risk Term NeonatesDocument6 pagesEarly Identification of Cerebral Palsy Using Neonatal MRI and General Movements Assessment in A Cohort of High-Risk Term Neonatesarif 2006No ratings yet

- DMCN 14205Document8 pagesDMCN 14205rgo17No ratings yet

- Mor 2016Document9 pagesMor 2016Farin MauliaNo ratings yet

- Prader Willi Syndrome AAFP PDFDocument4 pagesPrader Willi Syndrome AAFP PDFflower21No ratings yet

- Successful Fetal Tele-Echo at A Small Regional HospitalDocument8 pagesSuccessful Fetal Tele-Echo at A Small Regional HospitalDesi DaruNo ratings yet

- Precocious PubertyDocument11 pagesPrecocious PubertyRo RojasNo ratings yet

- Neurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaDocument10 pagesNeurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaJesusMiguelCorneteroMendozaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Neurology: David Dufresne MD, Lynn Dagenais BSC, Michael I. Shevell MD Repacq ConsortiumDocument4 pagesPediatric Neurology: David Dufresne MD, Lynn Dagenais BSC, Michael I. Shevell MD Repacq ConsortiumNelviza RiyantiNo ratings yet

- AUR in ChildrenDocument1 pageAUR in ChildrenStaporn KasemsripitakNo ratings yet

- Neoplasia Vaginal, Abril 2022Document6 pagesNeoplasia Vaginal, Abril 2022rafael martinezNo ratings yet

- Study of Clinical Profile of Late Preterms at Tertiary Care Hospital, BangaloreDocument11 pagesStudy of Clinical Profile of Late Preterms at Tertiary Care Hospital, BangaloreInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- HIV PXDocument8 pagesHIV PXCarol VizcainoNo ratings yet

- Eight Principles For Patient-Centred and Familycentred Care For Newborns in The Neonatal IntensiveDocument6 pagesEight Principles For Patient-Centred and Familycentred Care For Newborns in The Neonatal Intensivelilianajara.toNo ratings yet

- Considerations On The Use of Neonatal and Pediatric ResuscitationDocument15 pagesConsiderations On The Use of Neonatal and Pediatric ResuscitationrsmitrahuadaNo ratings yet

- Population Case-Control Study of Cerebral Palsy: Neonatal Predictors For Low-Risk Term SingletonsDocument9 pagesPopulation Case-Control Study of Cerebral Palsy: Neonatal Predictors For Low-Risk Term SingletonsFirdaus Septhy ArdhyanNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsFrom EverandPregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsNo ratings yet

- Mina Jahangiri, Fakher Rahim & Amal Saki Malehi: Scientific ReportsDocument13 pagesMina Jahangiri, Fakher Rahim & Amal Saki Malehi: Scientific ReportsAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging Versus Serum Iron Status As Diagnostic Tools For Pituitary Iron Overload in Children With Beta ThalassemiaDocument13 pagesMagnetic Resonance Imaging Versus Serum Iron Status As Diagnostic Tools For Pituitary Iron Overload in Children With Beta ThalassemiaAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Total Body Irradiation Versus Non-Total Body Irradiation Containing Regimens For de Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia in ChildrenDocument7 pagesComparison of Total Body Irradiation Versus Non-Total Body Irradiation Containing Regimens For de Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia in ChildrenAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- Sponsored Supplement Publication ManuscriptDocument14 pagesSponsored Supplement Publication ManuscriptAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- Childhood Iron Deficiency Anemia Leads To Recurrent Respiratory Tract Infections and GastroenteritisDocument8 pagesChildhood Iron Deficiency Anemia Leads To Recurrent Respiratory Tract Infections and GastroenteritisAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- Therapy For Children and Adults With Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument23 pagesTherapy For Children and Adults With Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy and Child Health Outcomes in Pediatric and Young Adult Leukemia and Lymphoma Survivors: A Systematic ReviewDocument25 pagesPregnancy and Child Health Outcomes in Pediatric and Young Adult Leukemia and Lymphoma Survivors: A Systematic ReviewAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- Gain of Chromosome 21 in Hematological Malignancies: Lessons From Studying Leukemia in Children With Down SyndromeDocument16 pagesGain of Chromosome 21 in Hematological Malignancies: Lessons From Studying Leukemia in Children With Down SyndromeAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- 04 Reproductive Anatomy - Physiology - Fetal Structure 1Document10 pages04 Reproductive Anatomy - Physiology - Fetal Structure 1Gwen CastroNo ratings yet

- Nervous and Sensory Functions, Excretion and Osmoregulation Reproduction, Development and MetamorphosisDocument20 pagesNervous and Sensory Functions, Excretion and Osmoregulation Reproduction, Development and MetamorphosisAROOJ ASLAMNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@and 13509Document22 pages10 1111@and 13509Theylor RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Male Reproductive SystemDocument14 pagesMale Reproductive Systemhomospin2014100% (1)

- Hormone Feedback & PregnancyDocument11 pagesHormone Feedback & Pregnancymaricaruba9No ratings yet

- Week 7-LS2 (Human Reproductive System) - WorksheetsDocument7 pagesWeek 7-LS2 (Human Reproductive System) - WorksheetsRheymund CañeteNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Male Infertility by The World HealthDocument7 pagesPrediction of Male Infertility by The World HealthquickdannyNo ratings yet

- Human Sexuality: Mohammad FananiDocument54 pagesHuman Sexuality: Mohammad FananiPutri AprilianiNo ratings yet

- Chapter-8-How Do Organisms ReproduceDocument8 pagesChapter-8-How Do Organisms Reproduceapi-400692183No ratings yet

- Anatomy of The Female Pelvis FinalDocument209 pagesAnatomy of The Female Pelvis FinalMignot Aniley86% (14)

- Case StudyDocument26 pagesCase StudyGrace Orencia100% (1)

- Disordered Proliferative Endometrium Causes and SymptomsDocument7 pagesDisordered Proliferative Endometrium Causes and SymptomsMuhammad BabarNo ratings yet

- PcosDocument72 pagesPcosDedy Tesna AmijayaNo ratings yet

- Year 4 5 Lesson 1 Growing and Changing Home Learning Lessons On PubertyDocument16 pagesYear 4 5 Lesson 1 Growing and Changing Home Learning Lessons On PubertyMaria Cravioto SantiagoNo ratings yet

- A Review and Current Situation of Pcos With InfertilityDocument15 pagesA Review and Current Situation of Pcos With InfertilityIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Notes Science Modes in Reproduction PLANTSDocument3 pagesNotes Science Modes in Reproduction PLANTSmary-ann escalaNo ratings yet

- Physiology of ReproductionDocument34 pagesPhysiology of ReproductionCalcium QuèNo ratings yet

- Performance Task 1Document3 pagesPerformance Task 1Jellie May RomeroNo ratings yet

- Case Scenario 1 For StudentsDocument9 pagesCase Scenario 1 For StudentsPrince DetallaNo ratings yet

- 3current Evaluation of Amenorrhea - A Committee OpinionDocument9 pages3current Evaluation of Amenorrhea - A Committee Opinionjorge nnNo ratings yet

- Pembiakan: Fo F Galeri Info G A L e R N Gal FDocument10 pagesPembiakan: Fo F Galeri Info G A L e R N Gal FAZALIDA BINTI MD YUSOF -No ratings yet

- Animals With BackbonesDocument19 pagesAnimals With BackbonesDiyonata KortezNo ratings yet

- Flow Chart For Menstrual Cycle: © WWW - Teachitscience.co - Uk 2016 25764 Page 1 of 2Document2 pagesFlow Chart For Menstrual Cycle: © WWW - Teachitscience.co - Uk 2016 25764 Page 1 of 2SarahNo ratings yet

- Unit XDocument18 pagesUnit XPreeti ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Puberty Is The Time When Our Body Changes PhysicallyDocument3 pagesPuberty Is The Time When Our Body Changes PhysicallyDemelzå SasotaNo ratings yet

- DLP - Menstrual CycleDocument5 pagesDLP - Menstrual CycleRigel Del CastilloNo ratings yet

- Hormone Therapy For Prostate CancerDocument10 pagesHormone Therapy For Prostate CancerChrisNo ratings yet