Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Luxacion Semilunar

Uploaded by

John Sebastian ValenciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Luxacion Semilunar

Uploaded by

John Sebastian ValenciaCopyright:

Available Formats

n Review Article

Evaluation, Management, and Outcomes

of Lunate and Perilunate Dislocations

Avi D. Goodman, MD; Andrew P. Harris, MD; Joseph A. Gil, MD; Joseph Park, BS; Jeremy Raducha, MD;

Christopher J. Got, MD

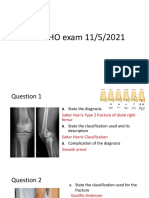

aspect. The 4 stages (Table 1) of injury

abstract progression were originally described by

Mayfield et al (Figure 1), with the trans-

Lunate and perilunate dislocations are potentially devastating injuries that lunate/interlunate arc more recently de-

are often unrecognized at initial evaluation. Prompt recognition and treat- scribed.1,6,9-11 However, some variability

ment is necessary to prevent adverse sequelae, including median nerve in injury patterns results from differences

dysfunction, carpal instability, posttraumatic arthritis, reduced functionality, in force vectors and transmission paths.

and avascular necrosis. In patients who are surgical candidates, operative

intervention is warranted to restore carpal kinematics and provide optimal Evaluation

outcomes. [Orthopedics. 2019; 42(1):e1-e6.] Although perilunate dislocations may

occur in isolation, when they occur during

high-energy trauma, Advanced Trauma

P

erilunate dislocations are severe evaluation, management, and understand- Life Support protocols should be followed

pan-carpal injuries that can pres- ing of perilunate and lunate dislocations for evaluation and resuscitation. Addition-

ent in the setting of high-energy are essential. al injuries should be addressed as they are

trauma, and they involve the dissociation discovered, with particular attention paid

of 1 or more of the lunate articulations. If Mechanism of Injury to the ipsilateral upper extremity.

a complete dislocation occurs, this injury Perilunate and lunate dislocations typi- Acute perilunate dislocations typically

is termed a lunate dislocation. Given the cally result from an axial load causing hy- present with pain and swelling over the

severity of confounding injuries, delayed perextension, intercarpal supination, and dorsal and/or volar aspect of the carpus,

presentation, difficult radiographic in- ulnar deviation of the wrist.4,5 In 1980, often with dorsal wrist tenderness over

terpretation, and occasional spontaneous Mayfield et al6 originally described this

The authors are from the Department of Or-

reduction, up to 25% of perilunate dis- method by forcing 32 wrists into hyper- thopaedics (ADG, APH, JAG, JR, CJG), Warren

locations are diagnosed weeks to years extension by applying force to the thenar Alpert Medical School, Brown University (JP),

after the initial injury.1 Although most eminence and recording the injury pat- Providence, Rhode Island.

The authors have no relevant financial rela-

of these injuries have radiographic evi- tern. Most perilunate injuries are asso-

tionships to disclose.

dence of posttraumatic arthritis regardless ciated with high-energy trauma—most Correspondence should be addressed to:

of treatment, a delay in recognition and commonly falls from height, followed Andrew P. Harris, MD, Department of Ortho-

treatment of perilunate dislocations wors- by motor vehicle collisions.7,8 This axial paedics, Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown

University, 593 Eddy St, Providence, RI 02903

ens already tenuous outcomes, including force results in a predictable pattern of

(Aharri26@gmail.com).

median nerve dysfunction, carpal instabil- injury. Beginning from the radial aspect Received: November 12, 2017; Accepted:

ity, reduced functionality, and avascular of the carpus, the force advances through March 7, 2018.

necrosis.2,3 Therefore, the proper initial the midcarpal region, toward the ulnar doi: 10.3928/01477447-20181102-05

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 | Volume 42 • Number 1 e1

n Review Article

Radiographic Findings and

Table 1 Classification

Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique

Progression of Perilunate Injuries (Mayfield Classification)

radiographs of the wrist must be obtained

Stage Description

during initial evaluation. Lateral radio-

I—Scapholunate dissociation Force is initially transferred directly through the scaph- graphs with normal findings should reveal

oid, resulting in a transscaphoid fracture or tear through

the scapholunate ligament, leading to a scapholunate a collinear axis of the radius, lunate, and

dissociation capitate (Figure 2).9 This longitudinal

II—Perilunate dislocation The injury travels as a series of ligament disruptions axis may be interrupted by displacement

around the lunate, from radial to ulnar, starting with the of the capitate in relation to the radius,

disruption of the lunocapitate association

indicating a perilunate dislocation of the

III—Triquetrum dislocation Disruption of the lunotriquetral interosseous ligament

and lunotriquetral ligament separates the carpus from same direction.8 Posteroanterior radio-

the lunate. The lunate dislocates dorsally, misaligning graphs should also be assessed for any

both the carpus and the lunate with the distal radius. patterns of instability. The 3 arcs of Gi-

IV—Lunate dislocation Disruption of the dorsal radiolunate ligament causes a lula’s lines, smooth and continuous carpal

palmar lunate dislocation into the carpal tunnel. The

remaining carpus often self-reduces. lines on the anteroposterior/posteroanteri-

or radiograph, consist of the borders of the

radiocarpal row, the midcarpal row, and

the proximal surface of the distal carpal

row (Figure 3).12 Any disruption of these

arcs suggests a lunate, perilunate, and car-

pal dislocation or fracture, respectively.7,12

Advanced imaging is rarely indicated in

the initial evaluation of ligamentous peri-

lunate dislocations; however, a computed

tomography scan may aid the diagnosis of

and better define some carpal bone frac-

tures.

Perilunate injuries are most commonly

classified using the system of Mayfield et

al6 (Figure 1, Table 1). In a stage I injury

(disruption of the scapholunate ligament

or transscaphoid fracture), radiographs

may reveal a widening of the scapholu-

nate space. The images should also be

Figure 1: Sequential pattern of perilunate injury progressing to lunate dislocation. The 4 stages of perilu- carefully inspected for a scaphoid or other

nate injury progress from I to IV in a clockwise fashion: (I) disruption of the radioscaphocapitate ligament carpal bone fracture.

(orange line) and scapholunate ligament (blue line), or fracture through the scaphoid; (II) disruption of A stage II injury (lunocapitate articu-

the lunocapitate articulation (yellow line) or fracture through the capitate; (III) lunotriquetral ligament (red

lation disruption) often presents with the

line) or fracture through the triquetrum; and (IV) radiolunate ligament (green line).

capitate dislocated dorsally, in addition to

stage I findings. A posteroanterior view

the scapholunate ligament, limited range tations, a thorough neurovascular assess- of a perilunate dislocation may reveal an

of motion, and frank deformity.7 However, ment and orthogonal radiographs are nec- overlap of the distal and proximal carpal

low-impact injuries may result in minimal essary to obtain a better understanding of rows with possible scaphoid fracture and

deformity with or without any associated the extent of injury.9 If median (or other) subluxation.7 An overlap of the triquetrum

nerve or tendon damage. The lunate may nerve compromise exists (eg, acute pares- on the lunate suggests a stage III perilu-

dislocate into the carpal tunnel or self- thesias or abnormal 2-point discrimina- nate injury (disruption of the lunotriqu-

reduce entirely, depending on the kinetic tion in the median nerve distribution), this etral interosseous ligaments), and an as-

profile and mechanism of injury. Given adds urgency to the treatment algorithm sociated volar fracture of the triquetrum

the spectrum of possible clinical presen- and must be documented. may be exhibited.7

e2 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

n Review Article

With a stage IV injury, a lunate disloca-

tion, rotation of the lunate in the volar di-

rection presents as a triangular appearance

known as the “piece of pie” sign (Figure

4) on a posteroanterior view. This rotation

in the lateral view yields the “spilled tea-

cup” sign, in which the lunate resembles a

teacup tipped in the volar direction.7

Alternatively, perilunate dissociation

injuries may be described using the arc

methodology: the loading mechanism re-

sults in fracture through the greater arc, Figure 3: Anteroposterior radiograph of the right

ligamentous disruption through the lesser wrist with normal findings showing Gilula’s 3 car-

arc, and/or fracture through the translunate/ pal arcs.

interlunate arc13 (Figure 5). Greater arc in-

jury results in fracture of the respective car- of displacement was predominantly dorsal

pal bone or radial styloid, whereas lesser (97%) compared with volar (3%).3

arc injury is associated with ligamentous

disruption.6 Mayfield et al6 showed that Management

higher velocity axial loads result in pure- Closed Reduction and Immobilization

ly ligamentous injury of the lesser arc, Carpal dislocations require urgent hand

whereas lower velocity axial loads tend to surgery consultation. Studies comparing

result in fractures within the greater arc. As nonsurgical with surgical intervention

described by Mayfield et al,6 the greater have consistently shown better outcomes

arc begins at the scaphoid, traverses the for the latter.9 Because of the disruption of

capitate, and ends at the triquetrum (Fig- Figure 2: Lateral radiograph with normal findings structurally crucial ligaments, closed re-

revealing a collinear axis of the radius (red), lunate

ure 5). Perilunate or lunate dislocations (yellow), and capitate (green). duction and immobilization alone is inad-

that only involve greater arc fractures are equate to provide necessary architectural

described by the fractures involved.1,6 For support.

example, an associated scaphoid fracture In 2008, the translunate arc concept was Closed reduction and splinting is more

is described as a transscaphoid perilunate described by Bain et al11 (Figure 5). Ap- effective with perilunate dislocations and

dislocation, a scaphoid fracture with a proximately 34 cases have been reported in less so with lunate dislocations because

capitate fracture is termed a transscaphoid, the literature since 1976.10 This arc may be of the extent of ligamentous damage.7

transcapitate perilunate dislocation, and more easily understood as fracture of the Initial management of lunate dislocations

so on. Each of these fracture fragments is lunate associated with ligament disruption involves a closed reduction and immobili-

associated with its respective ligament of on the opposite end of the greater arc.10 All zation using a sugar-tong splint.9 Patients

the lesser arc. The intact scapholunate and injuries can occur in isolation or in combi- are discouraged from applying any axial

lunotriquetral ligaments remain in continu- nation with another type (Figure 6). load to the injured wrist.

ity to the scaphoid, capitate, and triquetral Approximately 60% of perilunate inju- Under intravenous sedation (either a

fracture fragments.1,2,6 ries present with transscaphoid fractures, benzodiazepine such as diazepam or seda-

The lesser arc represents the ligamen- 72% of which are transverse fractures tives such as propofol), the patient’s arm

tous injuries that may occur.6 As with through the middle third.14 In a retrospective is held in longitudinal traction prior to

greater arc injuries, the force pattern pro- multicenter study of 166 perilunate disloca- (or during) the reduction attempt. Hang-

gresses from radial to ulnar. The lesser arc tions, perilunate fracture-dislocations were ing the hand in finger traps with weight

begins at the scapholunate ligament, tra- more common than ligamentous perilunate hanging from the biceps may be a useful

verses the lunocapitate joint and lunotri- dislocations, occurring at a ratio of 2 to 1.3 adjunct, as countertraction is mandatory

quetral ligament, and ends at the short ra- In the same series, dorsal transscaphoid to achieve sufficient distraction for reduc-

diolunate ligament (Figure 5).6 The fourth perilunate fracture-dislocations accounted tion. The classic teaching at the authors’

stage (short radiolunate ligament disrup- for 96% of perilunate fracture dislocations institution is 10-10-10: 10 mg of diaze-

tion) results in a lunate dislocation.2 and 61% of the entire series.3 The direction pam, hanging in 10 pounds of traction, for

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 | Volume 42 • Number 1 e3

n Review Article

Figure 5: Anteroposterior radiograph of a left wrist

showing the greater arc (A), lesser arc (B), and

translunate arc (C). Injury to the greater arc results

in transscaphoid, transcapitate, and/or transtri-

quetral fracture. The lesser arc injuries result in

scapholunate, lunocapitate, and/or lunotriquetral

Figure 4: A stage IV lunate dislocation. Note the “piece of pie” sign on the anteroposterior (A) and oblique ligament injury. Injury to the translunate arc results

(B) radiographs and the “spilled teacup” sign on the lateral (C) radiograph. in lunate fracture. All injury arc patterns may occur

in isolation or in combination.

are not amenable to early definitive open

reduction and internal fixation. Associated

comminuted distal radius fractures, severe

soft tissue injuries, and severe ligament

disruption may require spanning external

fixation for additional stabilization and

result in further complications.9 The use

of external fixation with percutaneous K-

wire fixation has shown acceptable return

to work and satisfactory functional and

Figure 6: Anteroposterior (A), oblique (B), and lateral (C) radiographs of a left wrist showing a transscaph- radiographic outcomes in most patients at

oid, transtriquetral perilunate fracture-dislocation associated with a distal radius fracture. 3 years.18

Open reduction and internal fixation

10 minutes before attempting reduction. Surgical Management and closed reduction with percutaneous

The precise reduction maneuver depends A variety of surgical options have been pinning have been shown to have better

on the patient’s injury; however, for the proposed for treatment: closed reduction long-term outcomes than closed reduc-

most common dorsal perilunate disloca- with percutaneous pinning (Figure 7), tion and casting.3,19,20 Open reduction

tions, the patient’s wrist is held in longi- open reduction and internal fixation, ar- can be performed through volar or dorsal

tudinal traction and the surgeon’s thumb throscopic repair, external fixation, and surgical approaches or through a com-

is placed on the volar aspect of the lunate acute proximal row carpectomy. Regard- bination of the 2. The volar approach is

and used to apply a dorsal-directed force less of fixation method, patients should be favorable when the lunate has dislocated

while the wrist is slowly brought into managed acutely—within 6 weeks of in- volarly, as beginning with the side of dis-

flexion, guiding the lunate back into the jury—as late treatment may impact surgi- location allows primary reduction of the

radiolunate fossa and lunocapitate articu- cal outcomes because of fibrosis, soft tis- lunate and provides easy access to release

lation.9,15 Described as the “paradox of re- sue scarring, and avascular necrosis.9,16,17 the transverse carpal ligament. The volar

duction,” restoration of the scapholunate Herzberg et al3 reported that perilunate approach also allows for direct repair of

relation by means of radial deviation re- dislocations/fracture dislocations treated the volar capsule’s space of Poirier, be-

sults in a widening of the torn palmar liga- 6 weeks after injury or those with open tween the volar radiocapitate and the

ments and the inability to restore scaphoid injuries had significantly worse clinical volar radiotriquetral ligaments, through

flexion, which would, conversely, require outcome scores (P<.05) than those treated which the lunate typically dislocates. It

ulnar deviation for correction.6,9 within 6 weeks. Certain injury patterns also allows repair of the volar lunotriqu-

e4 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

n Review Article

etral ligament and removal of any osteo-

chondral fragments.9

Alternatively, the dorsal approach pro-

vides direct access to the carpus, which

is optimal for realignment. The scaph-

oid and other fractured carpal bones, as

well as the scapholunate interosseous

ligament, are accessible for direct re-

pair. The volar lunotriquetral and dorsal

scapholunate interosseous ligaments are

the strongest portions of their respective

ligaments. Proper exposure and restora-

A B

tion of the scapholunate interosseous liga-

Figure 7: Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the wrist following closed reduction and

ment is believed to play a significant role percutaneous pinning of a lesser arc perilunate dislocation.

in a successful long-term outcome.9 The

combined dorsal–volar approach offers

the advantages of both approaches and al- sial.9 Even with these options, inappro- Conclusion

lows the surgeon complete visualization priate (or no) initial treatment risks poor Perilunate and lunate dislocations are

and dual access to all structures requiring outcomes. severe injuries that warrant vigilance in

repair.9 The complexity of the intercarpal patients with a concerning mechanism of

relationship disruptions involved in lunate Complications injury. After a radiographic and clinical

dislocations often requires the combined Despite predictable injury patterns, lu- workup, the dislocation must be addressed

dorsal–volar approach.21 nate and perilunate dislocations are often with prompt reduction and splinting, often

Other techniques have been described misdiagnosed, leading to serious compli- followed by surgery. All operative tech-

with mid-term outcomes comparable to cations and a poor clinical prognosis. For niques have similar mid- to long-term-

those of open reduction and internal fixa- various reasons, up to 25% of perilunate functional and radiographic outcomes,

tion. Kim et al22, showed that arthroscopic dislocations are undiagnosed or misdiag- so the authors recommend that surgeons

reduction and percutaneous fixation with nosed in the acute setting.7 Carpal inju- choose the method with which they are

K-wires and headless compression screws ries can often be overshadowed by more most comfortable and that is most suited

allows for minimal incisions and blood severe, life-threatening injuries sustained for the particular injury pattern.3,18,20,22,23

loss, with a lower rate of posttraumatic in the high-energy trauma. Furthermore, However, even the most effective treat-

arthritis on radiographs at an average radiographic images may be inadequately ment usually falls short of restoring nor-

follow-up of 31 months. Muller et al23 assessed or what they reveal may go un- mal function in these severe injuries, but

reported that acute proximal row carpec- recognized by a physician unfamiliar with early treatment can reduce the rates of

tomy can be used to manage perilunate perilunate or lunate dislocations.21 pain, instability, and nerve damage and

dislocations, with outcomes similar to Delayed treatment may result in re- improve functionality.

those of open reduction and internal fixa- duced functionality and range of motion,

tion at approximately 3-year follow-up. carpal instability, pain, and carpal tunnel References

The proximal row carpectomy group also syndrome from the palmar lunate dis- 1. Kennedy SA, Allan CH. In brief: Mayfield

benefited from a single surgical incision, locating into the carpal tunnel and com- et al. classification. Carpal dislocations and

progressive perilunar instability. Clin Orthop

a shorter operative time, and a shorter im- pressing the median nerve.7 Studies have Relat Res. 2012;470(4):1243-1245.

mobilization period.23 reported that patients who underwent sur- 2. Stanbury SJ, Elfar JC. Perilunate disloca-

Neglected perilunate injuries may be gical treatment exhibited signs of perma- tion and perilunate fracture-dislocation. J Am

Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(9):554-562.

managed using various salvage proce- nent damage at only 2 months after initial

dures, including proximal row carpec- injury, including progressive degenerative 3. Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, Ama-

dio PC, Cooney WP, Stalder J. Perilunate

tomy, wrist arthrodesis, and lunate ex- changes of the radiocapitate and midcar- dislocations and fracture-dislocations: a mul-

cision. However, given that there is no pal joints.24 Chronic carpal instability will ticenter study. J Hand Surg. 1993;18(5):768-

779.

consensus regarding the most appropriate ultimately progress to end-stage scaph-

4. Vitale MA, Seetharaman M, Ruchelsman

salvage procedure or the appropriate time olunate advanced collapse deformity of DE. Perilunate dislocations. J Hand Surg.

window, management remains controver- the wrist. 2015;40(2):358-362.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 | Volume 42 • Number 1 e5

n Review Article

5. Johnson RP. The acutely injured wrist Pourgiezis N. Translunate fracture with as- ous pinning. J Wrist Surg. 2015;4(2):76-80.

and its residuals. Clin Orthop Relat Res. sociated perilunate injury: 3 case reports with 19. Apergis E, Maris J, Theodoratos G, Pavlakis

1980;149:33-44. introduction of the translunate arc concept. J D, Antoniou N. Perilunate dislocations and

Hand Surg. 2008;33(10):1770-1776.

6. Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Car- fracture-dislocations: closed and early open

pal dislocations: pathomechanics and progres- 13. Gilula LA. Carpal injuries: analytic approach reduction compared in 28 cases. Acta Orthop

sive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg Am. and case exercises. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Scand Suppl. 1997;275:55-59.

1980;5(3):226-241. 1979;133(3):503-517. 20. Krief E, Appy-Fedida B, Rotari V, David E,

7. Perron AD, Brady WJ, Keats TE, Hersh 14. Marcuzzi A, Leigheb M. Transcapho perilu- Mertl P, Maes-Clavier C. Results of perilu-

RE. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: lunate nate dislocation with palmar extrusion of the nate dislocations and perilunate fracture dis-

and perilunate injuries. Am J Emerg Med. scaphoid proximal pole. Acta Bio-Medica At- locations with a minimum 15-year follow-up.

2001;19(2):157-162. enei Parm. 2016;87(suppl 1):127-130. J Hand Surg. 2015;40(11):2191-2197.

8. Gelberman RH, Cooney WP, Szabo RM. Car- 15. Tavernier L. Les Déplacements Traumatiques 21. Rettig ME, Raskin KB. Long-term as-

pal instability. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:123- du Semilunaire [master’s thesis]. Lyon, sessment of proximal row carpectomy for

134. France: University of France; 1906. chronic perilunate dislocations. J Hand Surg.

1999;24(6):1231-1236.

9. Scalcione LR, Gimber LH, Ho AM, Johnston 16. Garg B, Goyal T, Kotwal PP. Staged reduc-

SS, Sheppard JE, Taljanovic MS. Spectrum tion of neglected transscaphoid perilunate 22. Kim JP, Lee JS, Park MJ. Arthroscopic treat-

of carpal dislocations and fracture-disloca- fracture dislocation: a report of 16 cases. J ment of perilunate dislocations and fracture

tions: imaging and management. AJR Am J Orthop Surg. 2012;7:19. dislocations. J Wrist Surg. 2015;4(2):81-87.

Roentgenol. 2014;203(3):541-550. 17. Charalambous CP, Mills SP, Hayton MJ.

23. Muller T, Hidalgo Diaz JJ, Pire E, Prunières

10. Muppavarapu RC, Capo JT. Perilunate dislo- Gradual distraction using an external fixator G, Facca S, Liverneaux P. Treatment of acute

cations and fracture dislocations. Hand Clin. followed by open reduction in the treatment perilunate dislocations: ORIF versus proxi-

2015;31(3):399-408. of chronic lunate dislocation. Hand Surg. mal row carpectomy. Orthop Traumatol Surg

2010;15(1):27-29. Res. 2017;103(1):95-99.

11. Bain GI, Pallapati S, Eng K. Translunate

perilunate injuries: a spectrum of this uncom- 18. Savvidou OD, Beltsios M, Sakellariou VI, 24. Inoue G, Shionoya K. Late treatment of un-

mon injury. J Wrist Surg. 2013;2(1):63-68. Papagelopoulos PJ. Perilunate dislocations reduced perilunate dislocations. J Hand Surg

treated with external fixation and percutane- Edinb Scotl. 1999;24(2):221-225.

12. Bain GI, McLean JM, Turner PC, Sood A,

e6 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction

prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Perilunate Orthopedics Final ArticleDocument7 pagesPerilunate Orthopedics Final ArticleBogdan ManeaNo ratings yet

- Missed Monteggia FXDocument16 pagesMissed Monteggia FXEric RothNo ratings yet

- Classification and Management of Carpal DislocationsDocument18 pagesClassification and Management of Carpal DislocationsJunji Miller FukuyamaNo ratings yet

- Mano 4Document3 pagesMano 4juanNo ratings yet

- U10-Distal Radius FracturesDocument121 pagesU10-Distal Radius Fracturesrajasekhar ANo ratings yet

- Lunotriquetral CoalitionDocument3 pagesLunotriquetral Coalitionsuribabu963No ratings yet

- Anterior Decompression Techniques For Thoracic and Lumbar FracturesDocument10 pagesAnterior Decompression Techniques For Thoracic and Lumbar Fracturesmetasoniko81No ratings yet

- Stav SoucasnyDocument14 pagesStav SoucasnyTommysNo ratings yet

- Acutrak Fixation of Comminuted Distal Radial FracturesDocument4 pagesAcutrak Fixation of Comminuted Distal Radial Fracturessanjay chhawraNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Approach To Diagnosing Wrist Pain: Los Angeles, CaliforniaDocument6 pagesA Clinical Approach To Diagnosing Wrist Pain: Los Angeles, CaliforniaOtnil DNo ratings yet

- J Jhsa 2014 02 023Document6 pagesJ Jhsa 2014 02 023Lucas LozaNo ratings yet

- Bony SkierDocument6 pagesBony SkierChrysi TsiouriNo ratings yet

- The Use of A Transolecranon Pin in The Treatment of Flexion-Type SCFsDocument6 pagesThe Use of A Transolecranon Pin in The Treatment of Flexion-Type SCFsBariša KiršnerNo ratings yet

- Fractures of Distal Radius: An Overview: Family PracticeDocument8 pagesFractures of Distal Radius: An Overview: Family Practicesuci triana putriNo ratings yet

- Pao 2003Document12 pagesPao 2003Milton Ricardo de Medeiros FernandesNo ratings yet

- Art 1Document10 pagesArt 1Danilo LlumitasigNo ratings yet

- Basic Paediatrics - Unit 1 - SupracondylarDocument8 pagesBasic Paediatrics - Unit 1 - SupracondylarMohamad RamadanNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Carpal InstabilityDocument8 pagesAnalysis of Carpal InstabilityGiulio PriftiNo ratings yet

- Patellar Tendon RupturesDocument4 pagesPatellar Tendon Rupturesmarcelogascon.oNo ratings yet

- RG 2020190085Document18 pagesRG 2020190085zoom radiologiNo ratings yet

- Trauma C1 C2Document8 pagesTrauma C1 C2Karen OrtizNo ratings yet

- Fractures of Distal Radius An OverviewDocument8 pagesFractures of Distal Radius An OverviewNandani NarineNo ratings yet

- Ombro Pitfalls - CópiaDocument11 pagesOmbro Pitfalls - CópiaArthemizio LopesNo ratings yet

- Pédiatrie Elbow Trauma: An Orthopaedic Perspective On The Importance of Radiographie InterpretationDocument10 pagesPédiatrie Elbow Trauma: An Orthopaedic Perspective On The Importance of Radiographie InterpretationtripodegrandeNo ratings yet

- Kienbock's DiseaseDocument12 pagesKienbock's DiseaseVirtues GracesNo ratings yet

- Grupo A Additional Radiografic View of The Pelvic Limb in Dog PDFDocument8 pagesGrupo A Additional Radiografic View of The Pelvic Limb in Dog PDFLucia GarciaNo ratings yet

- 09.20-09.35 - DR - Dr.heri Suroto - When To OperateDocument80 pages09.20-09.35 - DR - Dr.heri Suroto - When To OperateJoseph WilsonNo ratings yet

- Displaced Fracture of The Waist of The Scaphoid: Instructional Review: Upper LimbDocument7 pagesDisplaced Fracture of The Waist of The Scaphoid: Instructional Review: Upper LimbantoanetaNo ratings yet

- 9 - Dislocations of The Digits PDFDocument42 pages9 - Dislocations of The Digits PDFFlorin PanduruNo ratings yet

- Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Reconstruction With Semi 2013 Arthroscopy TecDocument5 pagesMedial Patellofemoral Ligament Reconstruction With Semi 2013 Arthroscopy TecchinthakawijedasaNo ratings yet

- 2008 - Elbow Dislocation - OCNADocument7 pages2008 - Elbow Dislocation - OCNAharpreet singhNo ratings yet

- The Knee - Breaking The MR ReflexDocument20 pagesThe Knee - Breaking The MR ReflexManiDeep ReddyNo ratings yet

- Acute Distal Radioulnar Joint InstabilityDocument13 pagesAcute Distal Radioulnar Joint Instabilityyerson fernando tarazona tolozaNo ratings yet

- 2.8 Additional Radio Graphic Views of The Thoracic Limb in DogsDocument8 pages2.8 Additional Radio Graphic Views of The Thoracic Limb in DogsMiri MorganNo ratings yet

- Scapulothoracic Dissociation 2165 7548.1000142Document2 pagesScapulothoracic Dissociation 2165 7548.1000142Fadlu ManafNo ratings yet

- Displaced Acetabular FracturesDocument11 pagesDisplaced Acetabular FracturesJayNo ratings yet

- Imagenology of Canine Elbow DysplasiaDocument10 pagesImagenology of Canine Elbow DysplasiaMaría José RiveroNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Knee Dislocations Evaluation, Management, and Surgical TreatmentDocument15 pagesTraumatic Knee Dislocations Evaluation, Management, and Surgical TreatmentToño Solano NogueraNo ratings yet

- Osseous Fixation Pathways in Pelvic and Acetabular Fracture Surgery Osteology, Radiology and Clinical Applications 2011Document8 pagesOsseous Fixation Pathways in Pelvic and Acetabular Fracture Surgery Osteology, Radiology and Clinical Applications 2011Gonzalo JimenezNo ratings yet

- Proximal Femur Fractures: Sulita Turaganiwai s130364Document26 pagesProximal Femur Fractures: Sulita Turaganiwai s130364Wālē NandNo ratings yet

- Carroll 2012Document11 pagesCarroll 2012Yuri Chiclayo CubasNo ratings yet

- J Langford. Pelvic Fractures Part 1, Evaluation, Calssification and Resucitation. 2013Document10 pagesJ Langford. Pelvic Fractures Part 1, Evaluation, Calssification and Resucitation. 2013Bruno HazlebyNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento Quirurgico de Triada Terrible de CodoDocument9 pagesTratamiento Quirurgico de Triada Terrible de Codotraumatologia ortopediaNo ratings yet

- Managementofdistal Femurfracturesinadults: An Overview of OptionsDocument12 pagesManagementofdistal Femurfracturesinadults: An Overview of OptionsDoctor's BettaNo ratings yet

- Carpal Ligament InjuriesDocument21 pagesCarpal Ligament InjuriesMartin CuellarNo ratings yet

- Fracturesofthecarpal Bones: Brian M. Christie,, Brett F. MichelottiDocument9 pagesFracturesofthecarpal Bones: Brian M. Christie,, Brett F. MichelottiTeja Laksana NukanaNo ratings yet

- Mitral Valve Repair, How I Teach ItDocument5 pagesMitral Valve Repair, How I Teach ItLuqman AlwiNo ratings yet

- Pincerimpingement: Michael M. Hadeed,, Jourdan M. Cancienne,, Frank Winston Gwathmey JRDocument14 pagesPincerimpingement: Michael M. Hadeed,, Jourdan M. Cancienne,, Frank Winston Gwathmey JRdrjorgewtorresNo ratings yet

- Treatment Scapular Winging 2007Document7 pagesTreatment Scapular Winging 2007YassineNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing Treating Horse Back PainDocument5 pagesDiagnosing Treating Horse Back Paincamila uribeNo ratings yet

- The Peel-Back Mechanism Its Role in Producing and Extending Posterior Type II SLAP Lesions and Its Effect On SLAP Repair RehabilitationDocument4 pagesThe Peel-Back Mechanism Its Role in Producing and Extending Posterior Type II SLAP Lesions and Its Effect On SLAP Repair RehabilitationSamuelNo ratings yet

- Radiological Signs of A True Lunate Dislocation: Adam Tucker, William Marley, Angel RuizDocument2 pagesRadiological Signs of A True Lunate Dislocation: Adam Tucker, William Marley, Angel RuizjuanNo ratings yet

- Radiographic EvaluationDocument12 pagesRadiographic EvaluationLuis Gerardo Castillo MendozaNo ratings yet

- Ortho HO Exam NS AnswerDocument33 pagesOrtho HO Exam NS Answersarvesswara muniandyNo ratings yet

- Posttraumatic Boutonniere and Swan Neck Deformities Mckeon2015Document10 pagesPosttraumatic Boutonniere and Swan Neck Deformities Mckeon2015yerec51683No ratings yet

- Inside Out Menico RampaDocument6 pagesInside Out Menico RampaNilia AbadNo ratings yet

- Fracturas PatologicasDocument20 pagesFracturas PatologicasSamantha AriasNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Decision Making in The Unstable Elbow: Management of Simple DislocationsDocument8 pagesAssessment and Decision Making in The Unstable Elbow: Management of Simple DislocationsDr LAUMONERIENo ratings yet

- Fractura de MuñecaDocument13 pagesFractura de MuñecawilhelmNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Acute Lunate and Perilunate Dislocations: Hand. All Rights Reserved.)Document9 pagesTreatment of Acute Lunate and Perilunate Dislocations: Hand. All Rights Reserved.)John Sebastian ValenciaNo ratings yet

- AOT Tech Principles OperatingRoom Book Sample 16064029387223209Document36 pagesAOT Tech Principles OperatingRoom Book Sample 16064029387223209John Sebastian ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Critical Analysis ReviewDocument17 pagesPosterior Malleolar Fractures: A Critical Analysis ReviewJohn Sebastian ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Surgeon-Controlled Variables On Construct Stiffness in Lateral Locked Plating of Distal Femoral FracturesDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Surgeon-Controlled Variables On Construct Stiffness in Lateral Locked Plating of Distal Femoral FracturesJohn Sebastian ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Hand and Upper Extremity Anatomy: A Pocketbook Manual ofDocument144 pagesHand and Upper Extremity Anatomy: A Pocketbook Manual ofMakis MoralisNo ratings yet

- Managementofdistal Femurfracturesinadults: An Overview of OptionsDocument12 pagesManagementofdistal Femurfracturesinadults: An Overview of OptionsDoctor's BettaNo ratings yet

- Proximal Femur FracturesDocument191 pagesProximal Femur FracturesGreenIron9No ratings yet

- D. Slutsky, A. Gotow - Distal Radius Fractures (Issue of Hand Clinics, Ol 21 No 3) - Saunders (2005)Document232 pagesD. Slutsky, A. Gotow - Distal Radius Fractures (Issue of Hand Clinics, Ol 21 No 3) - Saunders (2005)John Sebastian ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Rev Jotv32n1s Issue Softproof 11218Document173 pagesRev Jotv32n1s Issue Softproof 11218pr4nks7erNo ratings yet

- Septicarthritisofnative Joints: John J. RossDocument16 pagesSepticarthritisofnative Joints: John J. RossAli ChaconNo ratings yet

- Malignant Pleural Effusion and Its Current Management A ReviewDocument21 pagesMalignant Pleural Effusion and Its Current Management A ReviewJohn Sebastian ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Imaging Musculoskeletal Trauma 3Rd Edition Donna G Blankenbaker Full ChapterDocument51 pagesDiagnostic Imaging Musculoskeletal Trauma 3Rd Edition Donna G Blankenbaker Full Chapterjohn.carlton594100% (4)

- How To Examine The Wrist and HandDocument7 pagesHow To Examine The Wrist and HandSurgicalgownNo ratings yet

- Ulnar NeuropathyDocument24 pagesUlnar NeuropathypaulosantiagoNo ratings yet

- Practicing Hand & Wrist ExercisesDocument20 pagesPracticing Hand & Wrist ExercisesRegino GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation - Closed Fracture Radius Ulna PediatricDocument30 pagesCase Presentation - Closed Fracture Radius Ulna PediatriciamboredtiredNo ratings yet

- Flexor Carpi Radialis Tendinitis - Hand - OrthobulletsDocument6 pagesFlexor Carpi Radialis Tendinitis - Hand - OrthobulletsSylvia GraceNo ratings yet

- Orthopaedic MCQDocument6 pagesOrthopaedic MCQGlucose DRglucoseNo ratings yet

- Zones of Hand: Rose Mary AntonyDocument36 pagesZones of Hand: Rose Mary AntonyFatra FasyaNo ratings yet

- Grammar: 1. Put The Verbs Into The Correct FormDocument18 pagesGrammar: 1. Put The Verbs Into The Correct FormSara Belén CamachoNo ratings yet

- Rad Ana Midterm Upper ExtremityDocument3 pagesRad Ana Midterm Upper ExtremityAlvin Karl ValenciaNo ratings yet

- 12 - Fractures & Dislocations of The Upper Limb-1Document84 pages12 - Fractures & Dislocations of The Upper Limb-1Ain Ul NoorNo ratings yet

- Madelung Deformity RadioscapholunateDocument7 pagesMadelung Deformity RadioscapholunateAnonymous bUBXIFfNo ratings yet

- Radiographic Image Analysis 4Document562 pagesRadiographic Image Analysis 4Jessica Ugalde Mata100% (1)

- Carpal Tunnel Surgery, Hand Clinics, Volume 18, Issue 2, Pages 211-368 (May 2002)Document151 pagesCarpal Tunnel Surgery, Hand Clinics, Volume 18, Issue 2, Pages 211-368 (May 2002)alinutza_childNo ratings yet

- Kienbock's DiseaseDocument12 pagesKienbock's DiseaseVirtues GracesNo ratings yet

- Clinical Significance of Upper LimbDocument3 pagesClinical Significance of Upper LimbflissxloveNo ratings yet

- Splinting, Orthoses, and Casting For Occupational Therapy StudentsDocument43 pagesSplinting, Orthoses, and Casting For Occupational Therapy StudentsNatalia RamirezNo ratings yet

- Nama Otot Origo Insersi Act Pectoralis MajorDocument8 pagesNama Otot Origo Insersi Act Pectoralis MajorWilliam Giovanni M, dr.No ratings yet

- Distal Radius FractureDocument30 pagesDistal Radius FractureronnyNo ratings yet

- Sam Splint User Guide Lowres CompressedDocument64 pagesSam Splint User Guide Lowres CompressedAbidi Hichem0% (1)

- Surface & Radiological Anatomy (3rd Ed) (Gnv64)Document226 pagesSurface & Radiological Anatomy (3rd Ed) (Gnv64)muzaqin100% (2)

- Practical Techniques in Injury Management: Casts and SplintsDocument30 pagesPractical Techniques in Injury Management: Casts and SplintsBodescu Adrian100% (1)

- Jurnal 1Document5 pagesJurnal 1Yakobus Anthonius SobuberNo ratings yet

- Upper Extremity Range of Motion: Erinda Rahma MuliaDocument25 pagesUpper Extremity Range of Motion: Erinda Rahma MuliaAdinda DianNo ratings yet

- Special Tests For WristDocument13 pagesSpecial Tests For WristSaif Ahmed LariNo ratings yet

- SHEPPARD, Joseph. Drawing The Living Figure (1984)Document147 pagesSHEPPARD, Joseph. Drawing The Living Figure (1984)arqevp100% (2)

- Active & Passive RomDocument3 pagesActive & Passive RomMuhammad IrfanNo ratings yet

- Atlas Puntos de Acupuntura PDFDocument421 pagesAtlas Puntos de Acupuntura PDFajardineraNo ratings yet

- Locomotor Homoeopathy PDFDocument80 pagesLocomotor Homoeopathy PDFmartincorbacho100% (1)

- Joints SummaryDocument2 pagesJoints SummaryMarta Noguero PueyoNo ratings yet