Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arms Race Instability and War

Uploaded by

Monsieur HitlurrrCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arms Race Instability and War

Uploaded by

Monsieur HitlurrrCopyright:

Available Formats

Arms Race Instability and War

THERESA CLAIR SMITH

Department of Pohtical Science

Rutgers University

Historically, half of the interstate wars identified by Singer and Small have been

preceded by arms racing; therefore, not all wars stem from weapons competition.

Similarly, there are arms races which end pacifically. Here, considering only arms race-

related conflicts, the author argues that war may be anticipated at the end of an arms race

on the basis of time-constrained mathematical stability characteristics of the involvement.

Simple linear models of arms racing are applied to a sample of historically founded

weapons competitions. Coefficients thus provided are used to determine the stability of

the arms races, using a time-restricted definition of interesting stability rather than

stability in the limit, to obtain a moderate rate of successful predictions. Stability analyses

with time constraints appear to provide a method for assessing part of the risk of a general

course of armament.

INTRODUCTION

Readers who in defiance of W. H. Auden have sat with statisticians

and committed social science are aware that asking the right questions is

an effort at least as important as producing the right answers.

Investigations of possible arms race/war connections have benefited

from several sets of probing questions (cf., Saaty, 1964, 1968; Gray,

1971, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1976; Wohlstetter, 1974; Caspary, 1967;

Smoker, 1965; Lambelet, 1971, 1975). These range from fundamental

questions about the existence and nature of arms racing (Wohlstetter,

1974; Gray, 1971, 1973, 1974) to detailed conjectures about realistic

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the

Political Science Department and the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota for

a prior set of analyses, and the Political Science Department and Research Council of

Rutgers University for these. The author is considerably indebted to Brian L. Job and

Hector Sussman for comments on this and earlier drafts.

JOURNAL OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION, Vol 24 No 2, June 1980 253-284

@ 1980 Sage Publications, Inc

253

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

254

models and forecasts of political outcomes. Many of the basic questions

remain unanswered. Whether arms races lead to war is one of the more

compelling and unresolved issues.

In the literature of war origins, war causation is presumed to be a

complex process involving many often interrelated variables. Several

measures of military power are predominant among them, either as

hypothesized causal or secondary catalytic agents.Choucri and North

(1975), in a broad examination of the antecedents of World War I,

consider several interrelated processes stemming from national growth,

including alliance-formation and rising military expenditures. Assum-

ing a more direct relationship between capabilities and war, Singer et al.

(1972) correlate measures of preponderance of power (including

military power) with war to indicate that concentrated power is

associated with more war in the nineteenth century and less in the

twentieth. Wallace (1972) also makes this arms-war connection explicit

in arguing that tensions created by inconsistencies between achieved and

ascribed status are transmuted into war mainly through their impact on

arms accumulation. Holsti’s view (Holsti et al., 1968; Holsti, 1972) that

arms racing adversely affects decisions made in crises is coherent with

Wallace’s research findings. Other authors also point to possible

involvement of changing weapons levels in adverse crisis decision-

making (cf., inter alia McClelland, 1968; Hermann, 1972; Halper, 1971).

If these researchers are correct, there may be, for a variety of theoretical

reasons, consistent relationships among arms racing patterns and war or

peace. If such relationships do exist, Lambelet (1971) is probably not

correct in contending that arms racing and hot wars are largely

independent. However, in particular cases hot wars may still occur

sans arms race, and arms racing may stabilize or end without war.

(For example, the Korean war apparently began without an arms race,

if the author’s definition is used.)

On the basis of argument and accumulated research findings

(Caspary, 1967; Smoker, 1964, 1965, 1969; Milstein, 1972; Wallace,

1970, 1971, 1972, among others), we may then reject the most absolute

views-that racing always ends in war (there are also races which end

without war-cf., Table 1) and that arms rivalries and wars are totally

unrelated. This leaves us considerable middle ground. Military com-

1. Note that by definition catalysts may serve not only to initiate a reaction but also

to accelerate an ongoing process.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

255

petition has been linked repeatedly to the outbreak of war in many

arguments and much historical and social science research (cf., Carr,

1939; Wright, 1942, Alcock, 1972, among others). If there are regu-

larities in this relationship between arming and war, there may exist

some class of arms races which is particularly war-prone. Distinguishing

such races from others would then become a matter of considerable

theoretical importance and practical utility. This article reports the

results of such an inquiry.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Any rigorous examination of this question must begin with a

definition. For the purpose of this study an arms race is understood as

the participation of two or more nation-states in apparently competitive

or interactive increases in quantity or quality of war material and/or

persons under arms. Though a race usually involves at least two

parties-independent states in this analysis-one may be far more

committed to racing than another. (One can imagine a state, racing in

isolation because of exaggerated fears of a potential opponent. It can

even be imagined that a state might race against a friendly nation just in

case the tide should turn, but presumably if racing posed a genuine or

publicly perceived threat to the erstwhile friend, the friendly nation

would eventually respond in kind.) The competition must last a

minimum of four years. An arms race then begins in a year for which

military spending rises and hostility toward some adversary nation-state

has been declared as government policy. (See appended comments.) A

race ends for a given participant when military spending falls for two

consecutive periods, the end point being the last year to show an

increase. (Some exceptions to these rules are made when it can be argued

that qualitative changes in arms probably account for spending

decreases, or when the construction of major new weapons systems

coincided with minor decreases in military spending.) In this definition a

race is also ended when war is declared between racing rivals. So the

units of analysis in this study are individual national records of military

spending while these are generally increasing, and while statements of

national officials indicate-if taken at face value-that increases are

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

256

made in response to or in anticipation of military moves of perceived or

potential adversaries. Thus a race is also ended when foreign policy is no

longer declared to be hostile between erstwhile rivals.

This choice of definition means, among other things, that not all

military spending constitutes arms racing, and not even all periods of

rising military outlays constitute arms racing, but only those coupled

with hostile or competitive foreign policy statements. A definition of

this kind is coherent with that of Colin Gray (1976: 3-4, 1971: 40) and

others except that it introduces some additional specifics. Gray writes

there should be two or more parties

perceiving themselves to be in an adversary

relationship, who are increasing or improving their armaments at a rapid rate and

structuring their respective military postures with a general attention to the past,

current and anticipated military and political behavior of the other parties.

In contrast, Wallace (1979) advances a definition of an arms race

which is somewhat more specific than the one employed here. The

foreign policies of the proposed racers must be interdependent. Beyond

this Wallace confines racing to the great powers (by the Singer and

Small criteria), to their allies, and to intervals of abnormal military

expenditures marked at the outset by sharp acceleration to growth

rates of 10-25% (or more). Wallace’s definition varies from that used

here in that his acceleration criterion is explicit and the set of candidate

nations is that group of nations of roughly equal power, and again, their

allies in some cases. However, there is broad agreement with the present

study in that races are treated dyadically, and periods of abnormal

military spending and interactive foreign policies are singled out.

PAIRING OF RIVALS

The definition set forth above assumes that arms racing, to be of

interest, is at least bilateral but may be multilateral. However, in

researching several histories for this investigation, the author concluded

that most arms races had in fact been completely or largely bilateral in

that most of a racing nation’s arming had been directed against one

adversary at a time, again accepting foreign policy statements at face

value. (This is not to say that there are not contingency plans for altering

any nation’s course of armament.) There are some questions about this

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

257

assertion for the great powers before the world wars, but without

exception one link required for a complete multilateral race is missing.

For example, while Germany armed against both France and England

before World War I, France and England did not race against each

other. Usually where there is multinational involvement in racing, as in

the Arab-Israeli case, the ongoing competition is still essentially

bilateral, with a coalition of sorts forming one side.

For these reasons, in this inquiry I have grouped adversaries or sets of

adversaries by pairs. Perhaps the recent case most likely to argue for an

exception to this bilateral treatment is provided by the Chinese-Soviet

and Soviet-American but even here, the third part of the

involvements,

triangle, a U.S.-Chinese race, would be extremely difficult to sub-

stantiate. It is true that the U.S. ABM was once justified in this context

by then Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, but this was largely in

response-apparently-to an objection that the ABM system as

envisioned would be an inadequate foil for Soviet attack. Since the

Chinese still have no missiles capable of reaching the United States (the

recent development of a longer-range ballistic missile in China indicate

this may not be so for long) this rationale appears flimsy. (Since the

ABM system is now dismantled, foreign policy generally seems less

antagonistic; and the United States is providing the PRC with a

surveillance satellite to observe Soviet Central Asia [cf., a number of

New York Times reports beginning with NYT, June 9, 1978, in which

US administration officials note an agreement to provide to the PRC

&dquo;airborne geological survey equipment using infrared scanning&dquo; which

would be denied to the USSR].) There seems to be at least as much

evidence for cooperation as for rivalry, especially since U.S. recognition

(January 1, 1979) and Chinese requests for increased U.S. military

presence in the western Pacific.

But this example does show that a country may race against more

than one opponent at a time; in this illustration consider that the USSR

apparently races with the United States and with the PRC simulta-

neously. When this occurs, the question of what proportion of the

military budget is directed toward each arms race naturally arises. Here

I have counted 100% of a multiple racer’s military spending against each

adversary in the multiple race. In doing so I probably exaggerate the

racing behavior of the multiple race participant by some unknown and

variable amount, but not to do so probably underestimates. The 100%

figure presumably does represent an accurate picture of worst case

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

258

military planning in opponents of multiple racers, since each opponent

could not afford not to contemplate the consequences of absorbing the

opposing multiple racer’s total military force, disregarding the dis-

tractions provided by other potential target nations. So this treatment

may nonetheless represent the way nations arm2, and is the tactic

adopted here. The mathematics of n-party races have been explored

(Richardson, 1960a; Smoker, 1965; Schrodt, 1978) and varying models

put forth. But their availability does not seem to be a sufficiently

compelling reason for their use unless a clear case for the additional

complexity can be made.

THE SAMPLE

There is exhaustive list of involvements which are generally

no

acknowledged constituted arms racing. This is so partially

to have

because the term has been used in a vague and overly generous manner,

and partially because an authoritative answer to the question &dquo;Where

are the arms races?&dquo; would require for its answer the services of several

dozen diplomatic historians and economists. However there are extant a

number of case studies (see e.g., Moll, 1968; Gray, 1975, 1976) and at

least one cautious selection of a small group of races (Huntington,

1958). As the author of the latter indicates, differences in definitions

result in disagreements among experts even on the relatively short list of

arms races which Huntington provides. Although some case studies and

Huntington’s suggestions can provide starting points for compiling a

sample of arms races, they do not go far enough to provide the substance

for a systematic general inquiry.

To attempt to provide a list of all recent arms races which could serve

as a sample of all arms races including future ones, the author obtained

military funding data extending back to about 1860. (There is nothing

magical about this date; it simply represents the point at which national

budgetary data become widely available. I do not argue that there were

2. Note that there is no practical method for obtaining more accurate estimates, since

even if these are matters of official record, which appears not generally to be the case, there

is some overlap in weapons, installations, and armed forces which could be employed with

approximately equal facility against either (or any) adversary. If this overlap exists, even if

"true" percentages of funds can be obtained, they should sum to more than 100.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

259

no arms races before this time, simply that nothing can be said about

them in the quantitative terms I would like to use.) Banks Cross-

National Time Series figures were supplemented with early military

budget estimates from the Almanach de Gotha and the Staleman’s

Yearbook. Post-World War II figures are taken from the Stockholm

International Peace Research Institute Arms Control and Disarmament

Yearbooks. A fairly complete and continuous record of military budgets

for most countries in the world at any given time in the 120 years from

1857 to 1977 was thus obtained. All increasing military appropriations

sequences of at least four years’ duration within this period were then

identified and investigated through historical sources. In the military

spending data there were well over 200 such sequences for individual

nations. When the foreign policies of the relevant countries were

researched, a list of thirty-two involvements which met the definitional

criteria was obtained. This list appears in Table 1. These involvements

clearly vary considerably in length, cost, commitment, and evident

intensity, but their differing among themselves in not, for example,

involving only rivalries inter pares does not alter their adherence to the

general definition proposed. (Readers may prefer an alternate or more

restrictive definition, or a reading of different historians. There is of

course reasonable scope for disagreement among area specialists,

quantitative historians and other writers on what &dquo;really&dquo; constitutes an

arms race.)

Here this list is accepted as a tolerable approximation of an arms race

inventory and is used as a basis for a quantitative inquiry into the racing

process.

WAR-PRONE RACES AND MECHANICAL STABILITY

It has been hypothesized that a class of war-prone races may exist;

there may be some type of race which, because of certain dynamics of the

spending patterns, tends to increase competition and result ultimately in

war.

Several ways to isolate war-prone races can be imagined, depending

on the speculations advanced on the relations between arms racing and

political events. It may be that some idiosyncratic factors affecting

individual decision-makers are crucial in some circumstances, so that

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

260

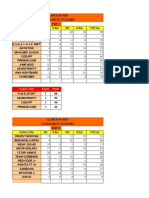

TABLE 1

Arms Races, 1860-1977

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

261

a. Military competition may be centered in only one part of the military, with a

particular service and/or weapons type receiving the most money and/or showing

rapid change in generations of weapons, transportation and delivery vehicles, or

sheer numbers of items deployed. If this appears to be so, the emphasized service

is noted under the &dquo;principal mode&dquo; heading. Development of nuclear weapons is

also noted here.

b. Cf., Hurewitz, 1969: 79; NYT, March 15, 1976. In the Times, a CIA official

addressing members of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics on

March 11, 1976 estimated Israel had 50 to 20 nuclear weapons &dquo;available for use.&dquo;

Then Director of CIA George Bush later accepted responsibility for the disclosure

of what was purportedly privileged information. Additionally, former U.S. Ambas-

sador to Morocco Robert E. Neuman has suggested to the author that Soviet war-

heads might have been transferred to Egypt for a brief period in the fall of 1973,

preceding the alert of U.S. forces. This is a rather durable rumor. (See SIPRI Year-

book, 1977 : 6.)

the most revealing work in this area would be that of the crisis decision-

making researchers. On the other hand it is possible that there are

certain large-scale deterministic factors which appear generally to be I

associated with the onset of war in the arms racing context, irrespective

of individuals in power. If so, some concepts which are helpful in

examining questions in the physical sciences may be applicable to this

problem, particularly the ideas of stability and instability in mechanical

systems. One way to examine arms races with a view to predicting their

outcomes could then be to consider them as mechanical systems which

may tend either toward a point of no further change, or to greater and

greater activity. (That is, consider arms races not as results of conscious

decisions but as physical systems working within certain bounds as a

result of some initial disturbance, as though arms racing were roughly

analogous to billiards.) One of the simplest ways to do this, if it is

assumed that a linear treatment is an adequate one for these purposes

and for the spending patterns under study, is to use the basic Richardson

models of arms races,3 shown later. If these models are accepted as

reasonable approximations of the arms racing process, the stability

coefficients which can be computed from them to determine their

mechanical stability may provide a useful indicator of the anticipated

outcome.

3. Presumably,someone has worked out the stability conditions for curvilinear

processes, but because this introduces the possibility of multiple points of equilibrium (?) it

seems excessively complex at this stage of the inquiry.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

262

To consider why this may be so, the reader should note that in

Richardson’s view (1960a), unstable races which tend toward ever-

increasing armaments exacerbate international tensions and eventually

incite violence. (&dquo;Eventually&dquo; is not defined.) This suggests that

Richardson’s notion of stability, regardless of its intrinsic importance

or the theoretical validity of the basic linear model, may yield a useful

indicator of dangerous races; unstable races may be more risky than

others. But this is only an assumption in Richardson’s work. To see

whether or not Richardson’s stability conditions criteria allow war

prediction in some instances, I will use his stability conditions with the

alterations made necessary by use of discrete rather than continuous

data to identify stable and unstable races in the mechanical sense

employed here. The groups of races thus labeled stable or unstable-for

stability is a characteristic of the race itself, not of individual nations’

participation in it-will then be separated by outcome to see whether

their stability characteristics have given any guide to outcomes in the

,

past, and whether the hints they make about continuing races seem

persuasive.

To explain why the stability characteristics of the models given below

might provide a useful indicator of oncoming war, the definition of

stability as Richardson adopts the term from mechanics must be

elaborated. Stability in this sense refers to the existence within some

mechanical system of a point of equilibrium at which change in the

process under study ceases. If a given physical system, or, in this case, a

set of equations important in predicting arms racing for two countries, is

in equilibrium, its rate of change is zero. In the arms racing context, this

point is not necessarily a point of disarmament, but represents the point

at which change in the arming process ceases, regardless of the absolute

levels it may have attained. If, on displacement, the system returns to

equilibrium, even though this takes a long time, it is stable.4 If the arms

race tends to drift (or &dquo;run&dquo;) away from equilibrium either positively or

negatively (i.e., in an increasing or decreasing direction), then the racing

system is unstable. (In my definition arms funding which is negatively

displaced, even though it manifests instability, does not constitute

racing, and so negative displacement is not considered at any length

here.) To put this another way, there are arms races which tend, in some

terms, to converge to a common point, and there are those which tend to

4. Bounded oscillation about an equilibrium point is not included here in the

discussion of stability, though a case of oscillation which dies down appears in the results.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

263

diverge. Those which tend to converge are considered likely to end

pacifically because they appear subject to some built-in limits. Those

which tend to diverge are expected to end in hostilities because of the

evidently unconstrained nature of the competition.

Thomas Brown ( 1971) gives a graphic description of stability in arms

racing which may be revealing at an intuitive level:

If arms racing for countries x and y is graphed on a coordinate plane with x and y

axes, the acceptable region for x is comprised of all points on or above the line

describing x’s current funding. The acceptable region for y is made up of all points

on or to the right of the line describing y’s current funding. If a race begins relatively

slowly there may be a large intersection of these areas within which the race may

proceed.

According to Brown, there are then two kinds of races-those which

display some mutually accepted regions of (positive) armament and

those which do not. Races which show these mutually accepted arming

regions tend toward rapid growth within this possibly large region and

are unstable. Stable races have no such intersecting acceptable regions,

and tend to be damped.

However, this does not mean that all arms races which show growth

are unstable. Growth only manifests instability if it continues away from

a point of equilibrium. There may be arms races which increase up to a

point of equilibrium; these would be stable, although conceivably at

high levels of armament. (Possibly SALT II-type agreements might

represent efforts to find such points, but only if the intent is for dx/ dt =

dy/ dt = 0 thereafter. This seems clearly counterfactual.) Similarly, it is

possible theoretically for an unstable race to be displaced negatively, so

that the tendency is for mutual rapid disarmament (akin, for example,

to the rapid divestiture of the trappings of high social positions in China

after the civil war). It is difficult to imagine a corresponding real life

situation, except perhaps competition in a munition which suddenly

became dangerous to store or deploy because of corrosion, chemical

instability or other complications.

Regardless of the illustrations we rely on, since we usually do not

observe arming nations at a point of zero change in armaments, it is more

accurate to say that there are some races which tend toward stability or

or instability in the long term. For convemence, these will be referred to

simply as stable or unstable races; that is, races whose every solution

remains bounded or approaches zero, and races whose solutions

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

264

explode. For a straightforward heuristic discussion of stability in the

Richardson models, see Zinnes (1976).

Note that this definition (which presumes the possible existence of

some point such that rates of change in arming are zero for both rivals) is

not the definition of stability used by deterrence theorists, crisis

decision-making researchers, or economists studying arming. It is

entirely possible for an arms competition to appear mechanically stable

at a point regarded by deterrence specialists as unstable in that the

character of some weapons system encourages preemptive attack. (For

other uses of the term, see McGuire, 1965.) This may help explain why

an occasional stable arms race will end in war or why, throughout some

unstable races, open conflict may be averted.

Let us consider what this means for the equations used here to

describe arms racing. In accepting the Richardson models for the

purposes of this initial investigation, we presume that an arms race looks

like:

in which the rate of change in arming for a given country x or y is an

additive linear function of perceptions (k, 1) of opponents’ weapons

minus the &dquo;fatigue and expense (a and /3) of keeping up the national

arsenal, plus grievances (g, h), which are assumed to be constant. (Signs

are allowed to vary.) If races may be so described, some simple

inequalities determine the stability or instability of the race. Richardson

(1960a) shows that for continuous functions instability results when the

product kl is greater than a/3; that is, when in the basic model the

product of the perceptual or &dquo;fear&dquo; factors is larger than the product of

the fatigue and expense coefficients. Stability is thus obtained when the

coefficients for the fear factors exceed those of the expense factors, as

might be expected if caution exceeds costs of military production in

some sense. Then arms build-ups tend to be depressed toward the origin.

So stability is a matter of coefficients in the continuous linear model and

can be expressed as a question of relative slopes. (See Richardson,

1960a; Zinnes, 1976; and Baumol, 1970, for a derivation and/ or a

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

265

treatment of the mathematics of stability.) The grievance terms may be

omitted from the determination of the stability coefficients because,

though they have a not inconsiderable impact in the real political world,

they serve in this model only to transpose the axes and do not affect the

coefficients themselves. That is, they set the starting points, the initial

levels of the competition, but not the shape of subsequent arms racing.

When discrete data are used, as in this case, stability conditions are

somewhat more complex than they appear in the Richardson example.

(All roots of the characteristic equation for the model must be less than

one in absolute value; see Baumol, 1970, esp. 213-227.) But here much

computational detail can be avoided because there are only two

independent variables, and borderline cases of neutral stability (cf., note

6) are omitted. Rearranging elements for convenience, we have two

equations describing an arms race as

in which signs are allowed to vary. To determine whether this system is

stable, the equations must be be rewritten in the form

from which

are derived. (The x and y variables are in the same sequence for both

racers for notational convenience.)

Assume, as an example, that accurate weights have been estimated as

follows:

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

266

Then the next step, writing the characteristic equation of the resulting

matrix5

gives

Solving the characteristic equation X2 + 3X - 6 = 0 via the quadratic

formula, we obtain

Two roots are now possible, depending on the sign on the second term in

the numerator above.6To approximate these lambdas

These values indicate stability directly when the borderline cases of

neutral or oscillatory stability have been excepted. If the solution of the

characteristic equation shows that one or both roots is greater than

unity in absolute value, then the equations describe an unstable arms

race. Calculations showing either one of the roots greater than 1 are

sufficient to show instability of the race. On the other hand, if the roots

are less than one in absolute value, then the equations describe a stable

race, one which tends to die down. (It is theoretically possible to obtain

borderline cases in which either one or both of the roots is exactly equal

5. The characteristic equation of any matrix [ cb

a ] is (a - λ) (d - λ) - bc = 0.

d

6. It is possible at this point to obtain imaginary numbers. In these cases complex

numbers a + bi emerge as roots. The interpretation of these results is not difficult (though

weird) since the same general observations about stability hold, and the absolute values of

a+b

| are obtained as 2

the roots |a + bi 2 (cf., Baumol, 1970: 210-212).

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

267

to I in absolute value. In these cases instability can occur, as can neutral,

oscillatory stability, so in such cases the determination of stability is

more involved. Since in the results presented here no such case (X = 1) is

obtained, no further discussion of these prospects is presented.)

In the above example, the first solution À1 = 1.37 suffices to show

instability. (To show stability, both lambdas would have had to be less

than one in absolute value.)

In the tables which follow the discussion of research strategy and

methods, coefficients estimated as per Ostrom (1978: 55-57), Malinvaud

(1966), Johnston (1972: 319-320), and others form matrices from which

the stability or instability of each adequately modeled arms race is

determined. For races which have ended, a comparison between

predicted and actual outcomes is made, and conjectures about con-

tinuing rivalries are advanced.

RESEARCH STRATEGY

To produce some results, the author took the list of arms races from

Table I and obtained estimates of military expenditures for as many

racers as possible, using the sources described in the section above titled

&dquo;the sample.&dquo; An attempt has been made in the SIPRI sources to include

disguised military expenditure from other budget headings, such as a

certain proportion of the All Union Science Budget to represent military

research and development spending in the USSR. Military aid is

included in the spending figures of the recipient nation. (Veterans’

benefits and payments on war debts are excluded.) These figures have

been converted to deflated U.S. dollars.

The research strategy then will involve fitting these data to the models

to estimate the stability coefficients, calculating the roots of the

characteristic equations from the matrices of coefficients to discover

whether stability or instability prevails for each race, and comparing

these expected results with the known outcomes of races which have

ended. Some speculations on outcomes of continuing races will

also be advanced. Readers who do not wish to be inconvenienced by a

discussion of statistical considerations may prefer to skip to the results

section.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

268

ESTIMATION PROCEDURE

If the Richardson models above are accepted as a reasonable if

simplified representation of arms racing between two states, stability of

the races thus represented may be determined by a statistical procedure

which estimates the coefficients reliably and allows the characteristic

equations to be solved. However, an ordinary least squares (OLS)

procedure is not necessarily appropriate. Determining the stability

coefficients in these models entails estimating an equation which

contains a lagged endogenous variable, and since arms racing is a time

series process, it probably exhibits autocorrelation in the error terms.

When serial correlation in the errors exists, the variances of the

coefficients are usually negatively biased, so that true standard errors

may be underestimated to some degree. The regression weights and their

significance tests may then attribute more importance to the lagged

variable than it actually merits, and less to any other regressors. Clearly

this could affect the stability comparisons crucially. The R2 and its

significance tests would also be exaggerated.

For these reasons, and the lagged endogenous variables pose an

especially serious estimation problem, OLS is no longer appropriate

because unbiased coefficients are not obtained. When lagged en-

dogenous variables and autocorrelation coexist in a model, the

estimates may be both biased and inconsistent (Hibbs, 1974: 290;

Malinvaud, 1966). This cannot be corrected by examining the OLS

residuals for error patterns, because these residuals do not in such cases

give an accurate picture of the disturbances. The usual tests will then

underestimate the actual degree of autocorrelation. Inclusion of one or

more exogenous variables will give an improved but not an entirely

accurate picture.

must then be determined through some other

Stability coefficients

method. Malinvaud suggests an instrumental variables technique to

compensate for the inconsistency obtaining in the presence of lagged

endogenous variables and possibly autocorrelated disturbances, but

notes a consequent loss of precision in the estimates (Malinvaud, 1966:

471; see also Johnston, 1972: 307). To provide estimates which are more

7. A relatively new test, Durbm’s h, has been developed precisely to fill the gap-to

estimate serial correlation when one or more lagged endogenous variables is present in a

regression. See Durbin ( 1970), Hopmann and Smith (1977), Ostrom ( 1978).

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

269

precise (Hibbs, 1974: 298) as well as consistent, the IV-pseudo GLS

procedure is adapted here (Ostrom, 1978: 557). According to Hibbs

(1974: 298) this technique allows more efficient estimates than either the

inappropriate OLS or the IV procedure alone.8

In these analyses no constraints were put on orsince it is argued cc

that they may be either positive or negative and practically any size.

These coefficients may, for example, be positive if arming is actually a

stimulus to the economy and hence to racing, and k and 1 may be

negative if the opposition appears overwhelming to the extent that

increments in weaponry are depressed. Of course, the coefficients may

also have the signs ordinarily given to them by Richardson.

RESULTS

As compared with the results of preliminary (regression) techniques

on the same data, these results show heightened contrast. The IV-GLS

procedure yielded results which fall into a distribution which is roughly

bimodal when racing is arrayed by R2, and which shows a strong

tendency toward high values of model fit for national participation in

arms racing (see Table 2). Most racing is very well fit; there are several

cases of extremely poor fit and relatively few intermediate cases.

Significance levels are correspondingly extreme. For twenty-two of

fifty-eight of these national military programs (38%), at least 80% of the

variance in national spending can be accounted for in relatively simple

linear models, though curvilinearity exists in some cases and may

provide useful diagnostic information in other analyses. (Part of this

curvilinearity is introduced by an apparent leap in racing immediately

8. The author notes that the small sample properties of this technique are evidently

unexplored. The assumptions underlying it include that the error structure approximates

AR (1). While this may not be the case, it is not a refutable assumption in these arms races

because the error structure cannot be determined empirically in small samples (in less than

30). Malinvaud (1966: 472) notes that because no methods exist for precise determination

of the form of serial correlation in the errors of brief time series, the choice of statistical

technique presents difficulties which are not encountered when only lagged endogenous

variables are involved (Malinvaud, 1966: 449). The Ostrom procedure seems to be one of

the few which takes some account of both of these issues. Since AR (2) and other more

complicated processes are relatively rare, a technique which makes the simplest possible

assumption in the absence of information should at a minimum provide a useful starting

point. There is apparently no known solution to the small sample bias problem.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

270

TABLE 2

Fit for Models in Final Step of IV-OLS Procedure

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

271

Table 2 (Continued)

a.Though Japan was building a modern navy at a furious pace, hence the race,

construction was evidently funded partially through scrappmg and recychng of the

old fleet. There is no change in the official Japanese military budget during the race,

m this anomalous case.

prior to war, an observation which is substantiated in other data using

dyads [Wallace, 1979: 14-15].)

In interpreting these results, two qualifications should be noted. The

first and most obvious is that, given repeated lags in the statistical

techniques employed, the results of extremely short races are probably

not useful, though they are included in the discussion. Second, a

reasonable interpretation of these results rests on an appropriate

application of the stability concept. Since stability refers to tendencies as

time approaches infinity, discovering these long-term characteristics

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

272

may be less meaningful for policy than determining whether races are

stable or unstable within the time span of the competition (&dquo;interestingly

stable&dquo;). This kind of qualification may also be of interest theoretically

since Richardson probably would not have predicted peace for an arms

race which was not appreciably damped until the year became

arbitrarily large.

A breakdown of arms races by model fit is made in Table 3 on the

basis of the goodness of fit for the nation receiving the lower R2 of the

two competitors. For category I, the well-modeled races, the average R2

is .91. In category II, moderately modeled races, the mean R2 is .61. In

the category of poorly fit races, III, the average R is .76, because of the

inclusion of some races with extremely good fit for one rival. Since much

of the dynamics of racing is not captured by linear models for at least

one side in the involvements listed under category III, calculations of

stability for these races would be misleading. The convergence of the

system (or its lack) cannot be determined here without good fits for both

participants, so all races in category III have been eliminated from the

further discussion of stability.

The mechanical tendencies of the well- and moderately modeled arms

races are presented in Table 4. Overall for ended involvements the rate

of correct prediction (postdiction) on the basis of in-the-limit char-

acteristics of the systems is an unimpressive 45% (5/ 11of more

accurately modeled terminated races). Approximately the same ratio

obtains when the extremely short races (n~8) are eliminated; there are

then four ended well-fit races (#2, 6, 12, 13) for which half the outcomes

are correctly indicated.

However, in the (noninfinite) short term, in which most arms racing

has taken place, stable involvements may not be much different from

unstable ones which are not exploding at prodigious rates. Consider an

extreme example, race 12, the Russo-Japanese competition, whose

solution is not greatly damped for about ninety years. This sort of

stability has little meaning in the context of outcome prediction for brief

involvements. It may then be useful to sort out short-term stable races

from longer-term stable races on the basis of some arbitrary criterion.

For our purposes an interestingly stable race will be an involvement

represented by a matrix for whose roots x, y the size of the solution9 is

damped to no more than 1 / 10th its initial magnitude within the span of

9. Size is defined as the vector x2+y 2 for solutions x + y. (To the vector belong the

spoils.) The point at which size is reduced to 1/ 10th its initial magnitude is determined here

as t = log . 1/log m, where m is the largest of the roots of the characteristic

equation.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

273

TABLE 3

Division of Arms Races by Accuracy of Linear Treatment

for the Poorer-Fit Nation of Each Pair

a. This average exceeds the average R2 in category II because of the coincidence of

extremely well-fit participation with extremely poorly-fit participation in the same

race. (See for example the second Indo-Pakistani race, R2 .205 for India, .939 for

=

Pakistan. This pair of results probably makes sense in view of the growing Chinese

military potential.)

the race. &dquo;Uninterestingly&dquo; stable races are indicated with an asterisk in

Table 4. If a peaceful outcome is only anticipated for cases of

interestingly stable arms racing, and &dquo;uninteresting&dquo; stability is con-

sidered not to differ significantly from instability within the span of the

race, correct predictions for ended races are obtained in approximately

82% (9/ 11) of these cases. When the extremely short races (n< 8) are

eliminated on methodological grounds, the rate of correct predictions is

5/7 or 71%.

Two ended races are incorrectly described regardless of the time

constraints on the stability concept. These are the Guatemalan-

Salvadorean race and the British-American one against Japan. These

erroneous predictions may be due in part to some anomalies in

Salvadorean military spending immediately prior to the 1885 war, in the

one case, and in the other perhaps to some confusion introduced by

treating the United States and the UK as a unitary actor, when there

were some interesting interactions between them during the period

under study.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

,~1)

Q)

U

C,3

1:4

Ë

~,

......

.,..,

== Q)

3

>-

’õ)

cq3

....

b

0

,~t

~’1:1

a

aa r.

c::

~ ~

« I

E-<::::= Q)

3

0

c;I)

U

w

.¡:

N

(.)

0

H

C,3

4.1

u

>1

s

Pm

tI)

274

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

~g

S

~3

Z0

0

c

b

~5

o

0

’3

’S

d

~.

’&.

_S

c

0

b

>.

I

<u;:j

(1)

~!

C

z >.

¡::

0 ~5

nt

U

1-

,It

(1) S

:D

co

0

H

N

t~

w

~5

’M

.fi

N

0

e

~~! 8 «

*&dquo;

~

Xj

~w

S ’3

N e

wo :;

’S

N

s-~

c~3 (U

* ~

275

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

276

Two of the three races continuing as of 1977, the Korean one and the

Eastern European one, have approximated or passed points of inter-

esting stability. In the Albanian case this seems plausible. Even though

Albania and the USSR still have no diplomatic, economic, or party

relations and periodically exchange perfunctory denunciations, the

involvement appears unlikely to end in war. The race seems to have had

essentially domestic driving forces in Albania and not to have exercised

a deciding effect on foreign military policy. Nor does Albania presently

seem physically capable of the sort of threat which would intrigue the

USSR sufficiently to overcome the considerable logistical and other

difficulties of a Soviet-Albanian war.

In Asia, the Korean case does not seem as clear. The volatility of the

Korean situation should not be underestimated, since the Koreas are

focal points of interest to the PRC as well as the United States and the

USSR, and since the region is one of the most heavily armed (per capita

or per square mile) in the entire world. However, it does appear that the

interested major powers have reached an implicit (if temporary)

agreement not to exacerbate Korean relations. Although there seems to

have been no overt settlement of the outstanding political issues in

Korea which would correspond to approaching the bounds of the arms

race, both the North and the South appear increasingly preoccupied

with domestic concerns: the North with the political future and the

health of Kim 11 Sung; and the South with dissent and most recently with

the assassination of Park Chung Hee, which occasioned a military alert.

According to these analyses, the U.S.-USSR competition has also

passed a point of interesting stability, about 1959-1960, which rep-

resents a period of intense foreign political contention and a prelude to

renewed active confrontation. This coincidence of damped solutions

and confrontation only serves to indicate that there are risk factors in

racing which are not encompassed at the level of abstraction of these

deterministic models. Although SALT II and other negotiations may

indicate a greater potential in the long term for real limits on weapons

competition between the superpowers, the military policies of each

appear inconsistent and unpredictable to the other, an impression

heightened by hardware and software failures (cf., the accidental US

NORAD nuclear alert on Nov. 9, 1979) and by &dquo;adventurism&dquo; abroad.

As perceived or actual advantages in preemption multiply, these

uncertainties may contribute to pressures for escalation in crises,

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

277

irrespective of the tendency of the Soviet-American race to be bounded.

Malfunction or unauthorized use of weapons systems may also create

crises. These risks are not assessed here, and neither is the probability of

deliberate war for anticipated gain.lo

The unobvious finding of interesting stability in the Soviet-American

race may also be a creature of the unit of analysis: it may be that this

involvement would show instability in some more specific terms, such as

the strategic weapons components of the budgets, and that it is this

surmise which influences expectations about the risks of the race.

In the whole sample of ended races there is a fairly substantial rate of

successful prediction (82%). When the extremely short races are

omitted, this rate falls to a moderate 71%. These results suggest that

where longer arms racing can be reasonably depicted in linear models,

political outcome may be moderately well predicted on the basis of time-

constrained stability characteristics of the involvement.

SUBSTANTIVE COMMENTS ON RESULTS

Recently some broad similarities in definition of cases and in

predicted outcomes of arms races have become apparent in independent

research. Rattinger’s (1976) Middle East races (1956-1967, 1967-1973)

have essentially the same time span (1957-1966, 1968-1973) and

participants (Israel vs. Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Libya) as are

employed here except that in this treatment the war years 1956 and 1967

are omitted. (Wallace excludes these involvements entirely, evidently

because of the status of nations in the region or the cut-off in the Singer

and Small data.) In assessing reactivity patterns, Rattinger has not

directly addressed the war prediction question. But he does discover that

the naval race 1956-1967 between Israel and Syria, Egypt and other

Arab countries was a &dquo;runaway&dquo; race in that disarmament of 10-30%

would have been required on Israel’s part to force the Arab growth rate

to zero. This discovery in naval data is coherent with the exponential

character of this race in aggregate expenditure terms; however, this race

10. An incomplete record of nuclear weapons accidents and delivery system accidents

appears in the SIPRI Yearbook 1977 (pp. 52-82). To date these have evidently been little

or remediable ones. We may, nonetheless, anticipate the patter of little fates.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

278

is necessarily poorly described in the linear models used in this study and

had to be removed from the present analyses, preventing a direct

comparison with Rattinger. (The first Middle East race, 1949-1955, is

uninterestingly stable in that its size is not appreciably diminished for

about 57 years.) For his second group of races Rattinger finds relatively

little reactivity, which is not entirely inconsistent with a race dying down

in 12 years, as calculated here.

From Wallace’s inventory of disputes (1979) it can be inferred that his

study and this one have identified a number of the same arms races and

some of the same results. The 1903-1904 Russo-Japanese war was

preceded by an arms race by both accounts: Wallace shows its index at

221.0 in 1904. Similarly the group of rivalries preceding World War I are

given high arms race index numbers: England and Germany in 1914,

133.0; France and Germany in 1914, 231.25. In 1939 the Russo-Japanese

race ended in war and is here shown to be uninterestingly stable, dying

down in 89 years. Wallace shows no dispute for Russia and Japan in that

year; however a prior calculation for 1938, a nonwar year, receives a low

index number, 14.96. The English and American involvement with

Japan ends here in war in 1940 and is stable, a disconfirming case. In the

Wallace study the U.S.-Japanese part of the involvement ends in 1941

with a large racing index of 314.58, and for the British-Japanese part in

1939, but no stability calculations were possible for that case. Wallace

shows disputes in 1936 and 1938 for these countries, neither of which

dispute has a high index number associated with it. The USSR and

Germany went to war in 1941 following a race by both accounts; the

racing index is 221.61 in 1941 and again, unfortunately, no stability

calculations have been made for this case. In one final case prior to

World War II, Wallace’s extremely large racing index (495.51) for

France and Germany in 1939 corresponds to a race which would not be

expected to die down until 1946.

There is a certain interlocking of Rattinger’s and Wallace’s results

with the ones presented in this analysis. Also, some consensus on the

historically available sample appears to be emerging in research on arms

racing, though this literature is not well reviewed here. Yet few specific

findings appear to be directly comparable. In general, various authors

have provided empirical support for the contention that arms racing is

risky, especially during periods of rapid acceleration or unusual

reactivity. These risks may arise through creation or escalation of crises,

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

279

technical accident, etc. (For a view of the war-preventing or postponing

functions of arms procurement in the Middle East, see Gray, 1975.)

CONCLUSIONS

There exists an overwhelming tendency for these discrete data

systems to be stable (i.e., bounded) in the long term even though there

has been a similarly powerful historical tendency for arms racing to end

in war relatively swiftly. If viewed somewhat simplistically, this

tendency toward stability in the limit leads directly to incorrect

predictions of short-term outcome. Prediction is considerably improved

by a consideration which takes into account the rate of convergence of

solutions over time. Then even the sparse and well-criticized Richardson

models produce nontrivial, if occasionally counterintuitive, results.

It is odd that there are no wildly explosive arms races here, as

indicated by roots in the neighborhood of 2 or larger. The absence of

rapidly exploding highly unstable races in these results may be due to the

omission of some of the more likely candidates such as Iran-Iraq, which

do not appear here because of poor fit to a linear model of arming for

one rival.

As Brown (1971) would have us expect, stable races in this group

apparently began with rapid rates of arming relative to the rates typical

of the unstable races; however, since the latter group comprises two

cases, this line of argument is conjectural. It may be that races initially

showing rapid acceleration in arming, which is generally alleged to be

destabilizing in the deterrence sense or with regard to likely immediate

foreign political repercussions, are actually mechanically stable, a

finding which would accentuate the importance of a time constraint in

the calculations. Races beginning more slowly might be unstable. This

may seem paradoxical; however, this development makes sense if

linearity is assumed to fail over the long term or for large x and y in arms

racing. Races showing tremendous early buildups may quickly approach

financial or political limits which cause them to level out, while in a

slower-growing race, the economy and political attitudes have a greater

opportunity to accomodate higher levels of military funding over time.

Stability as convergence to some set value is not synonymous with

stability in deterrence strategies. It may in fact be opposed to crisis

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

280

stability in foreign policy decision-making, if this discussion is correct,

since rapid arms buildups among possible opponents can increase the

incentives for precipitous actions.

Given the many simplifications and data problems encountered, the

substantial success rate for longer races here is encouraging. Addi-

tionally, if short-term stability is any guide, it may be possible to find

more and less risky ways to race, given that arms competition is a

persistent feature of the contemporary world, although this analysis

does not show exactly how this might be done. It would be interesting to

have a larger sample of peacefully ended races to investigate the

possibility that arming is good war prevention under some circum-

stances.

Generally, the problematic application to short time series of in-the-

limit characteristics of mathematical systems and the difficulty of

obtaining excellent fit to a linear model for both participants in all arms

races argue against the overconfident use of this particular strategy for

the future assessment of risk in any given rivalry. However, these results

do imply that interpretation of the stability of more complicated

systems&dquo; may prove useful for war forecasting, especially if more

realistic models are combined with a more precise examination of the

convergence of solutions within a time span relevant to particular arms

races.

APPENDIX:

FURTHER COMMENTS ON IDENTIFICATION OF CASES

To identify arms races, no exhaustive list of code words or phrases was

produced, as would be required for content analysis. Expressions of competi-

tiveness and hostility vary throughout the world by linguistic group, by culture,

and by time (e.g., &dquo;War Department&dquo; has lost cachet), though there may be some

undiscovered common core of such expressions in English. Instead the author

counted as hostile foreign policy statements any assertions of animosity or

rivalry-leaving these terms undefined-which identified both the speaker and

the target, and were linked to existing or projected military programs. Such

11. See, for example, the nonlinear (and discontinuous) treatments provided by

Wallace and Wilson, 1978.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

281

assertions often appear in national budget legislation and statements preceding

such legislation, as well as in statements of national military policy. Historically,

Japan and other nations have been very forthcoming in publishing ranked lists

of national enemies, thus providing some identification of major rivals and a

date for the beginning of a competitive foreign policy. (Whether or not there are

such statements for more than one year, the beginning of the race is set where

and if such statements coincide with increases in military expenditure.) It was

not necessary that these statements be publicly announced to be counted,

though a number of them were issued publicly amid some acclaim.

Examples of statements which would be accepted as sufficient indication of a

hostile/competitive foreign policy:

-The drive to arm China after 1860 can be documented through the government’s

&dquo;self-strengthening movement&dquo; against the barbanans, and through demands for

regular reports on the progress of the army.

-&dquo;Peru pursued no other objective than... to erase Chile from the waters of the

&dquo;

Pacific.&dquo;

-&dquo;Japan intends to get rid of the menace of the USSR.&dquo;

Some key phrases where adversaries have been identified:

-&dquo;30% increase in readiness,&dquo;

-&dquo;outbuild Germany by 8/4,&dquo;

-&dquo;balance our naval power,&dquo;

-&dquo;maintaining supremacy.&dquo;

Statements such as these are not always so clear-cut, so that a different

reading will produce a different time span for some races. Short case studies of

the arms races analyzed here are available on request.

REFERENCES

ALCOCK, N. (1972) The War Disease. Oakville, Ontario: Canadian Peace Research

Institute Press.

BAUMOL, W. J. (1970) Economic Dynamics. New York: Macmillan.

BROWN, T. (1971) "Models of strategic stability." Rand Corporation, Southern Cal-

ifornia Arms Control and Foreign Policy Seminar.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

282

CARR, E. H. (1939) The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939. New York: Harper & Row.

CASPARY, W. R. (1967) "Richardson’s model of arms races: description, critique and an

alternative model." Int. Studies Q. 2, 1.

CHOUCRI, N. and R. C. NORTH (1975) Nations in Conflict. San Francisco: W. H.

Freeman.

DURBIN, J. (1970) "Testing for serial correlation in least squares regression when some

of the regressors are lagged dependent variables." Biometrika 38, 3.

DHYRMES, P. J. (1971) Distributed Lags: Problems of Estimation and Formulation.

San Francisco: Holden-Day.

GRAY, C. S. (1976) The Soviet-American Arms Race. Lexington: Lexington Books.

(1975) "Arms races and their influence upon international stability with special

———

reference to the Middle East," in G. Sheffer (ed.) Dynamics of a Conflict. New York:

Rand McNally.

(1974) "The urge to compete: rationales for arms racing." World Politics 36,

————

2: 207-233.

---(1973) "Social science and the arms race." Bull. of the Atomic Scientists 29, 6: 2.

(1971) "The arms race phenomenon." World Politics 24: 39-79.

————

HALPER, T. (1971) Foreign Policy Crises: Appearance and Reality in Decision-Making.

Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill.

HERMANN, C. F. (1972) International Crisis: Evidence from Behavioural Research.

New York: Free Press.

HIBBS, C. A., Jr. (1974) "Problems of statistical estimation and causal inference in

time-series regression models," in H. L. Costner, Statistical Methodology, 1973-

1974. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

HOLSTI, O. R. (1972) Crisis Escalation War. Montreal: McGill-Queens Univ. Press.

——— R. NORTH, and R. A. BRODY (1968) "Perception and action in the 1914crisis,"

in J. D. Singer (ed.) Quantitative International Politics. New York: Free Press.

HOPMANN, P. T. and T. C. SMITH (1977) "An application of a Richardson process

model: Soviet-American interactions in the Test Ban negotiations 1962-1972." J. of

Conflict Resolution 21, 4.

HUNTINGTON, S. P. (1958) "Arms races: prerequisites and results." Public Policy

8: 41-86.

HUREWITZ, J. C. [ed.] (1969) Soviet-American Rivalry in the Middle East. New York:

Frederick A. Praeger.

JOHNSTON, J. (1963, 1972) Econometric Models. New York: McGraw-Hill.

LAMBELET, J. C. (1975) "Do arms races lead to war?" J. of Peace Research 12, 2.

(1971) "A dynamic model of the arms race in the Middle East, 1953-1965." General

———

Systems 16.

MALINVAUD, E. (1966) Statistical Methods of Econometrics. Chicago. Rand McNally.

McCLELLAND, C. A. (1968) "Access to Berlin: the quantity and variety of events

1948-1963," in J. D. Singer (ed.) Quantitative International Politics. New York:

Free Press.

McGUIRE, M. (1965) Secrecy and the Arms Race: A Theory of the Accumulation of

Strategic Weapons and How Secrecy Affects It. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ.

Press.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

283

MILSTEIN, J. S. ( 1972) "American and Soviet influence, balance of power, and Arab-

Israeli violence," in B. M. Russet (ed.) Peace, War and Numbers. Beverly Hills: Sage

Publications.

MOLL, K. (1968) The Influence of History Upon Seapower. Stanford: Stanford Research

Institute.

MORRISON, J. L. (1970) "Small sample properties of selected distributed lag estimates."

Int. Econ. Rev. 2.

OSTROM, C. W., Jr. (1978) Time Series Analysis: Regression Techniques. Beverly

Hills: Sage Publications.

RATTINGER, H. (1976) "From war to war: arms races in the Middle East." Int. Studies

Q. 20, 4.

RICHARDSON, L. F. (1960a) Arms and Insecurity: A Mathematical Study of the

Causes and Origins of War. Pittsburgh: Boxwood.

(1960b) Statistics of Deadly Quarrels. Pittsburgh: Boxwood.

———

SAATY, T. L. (1968) Mathematical Models of Arms Control and Disarmament. New

York: John Wiley.

(1964) "A model for the control of arms." Operations Research 12, 4.

———

SARGEANT, T. J. (1968) "Some evidence on the small sample properties of distributed

lag estimators in the presence of autocorrelated disturbances." Rev. of Economics

and Statistics 50.

SCHRODT, P. A. (1978) "Richardson’s N-nation model and the balance of power."

Amer. J. of Pol. Sci. 22, 2.

SINGER, J. D., S. BREMER, and STUCKEY (1972) "Capability distribution, uncer-

tainty and major power war 1820-1965," in B. M. Russett (ed.) Peace, War and Num-

bers. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

SMOKER, P. (1969) "A time series analysis of Sino-Indian relations." J. of Conflict

Resolution 13, 2.

(1965) "Trade, defense and the Richardson theory of arms races: a seven-nation

———

study." J. of Peace Research 4, 2.

(1964) "Fear in the arms race: a mathematical study." J. of Peace Research 1, 1.

———

SNYDER, G. H. (1961) Deterrence and Defense: Toward a Theory of National Defense.

Westport, CT: Greenwood.

SIPRI [Stockholm International Peace Research Institute] (1977) World Armaments and

Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1977. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell.

STEINER, B. (1973) Arms Races, Diplomacy and Recurring Behavior: Lessons From

Two Cases. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

WALLACE, M. O. (1979) "Arms races and escalation." J. of Conflict Resolution 23, 1.

(1972) "Status, formal organization and arms levels as factors leading to the

———

onset of war, 1820-1964," in B. M. Russett (ed.) Peace, War and Numbers. Beverly

Hills: Sage Publications.

(1971) "Power, status and international war." J. of Peace Research 8, 1.

———

(1970) "The onset of international war 1820-1945: a preliminary model." Univ.

———

of British Columbia. (mimeo)

and J. M. WILSON (1978) "Nonlinear arms race models" J. of Peace Research

———

25, 2.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

284

WOHLSTETTER, A. (1974) "Is there a strategic arms race?" Foreign Policy 15.

WRIGHT, Q. (1942) A Study of War. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

ZINNES, D. A. (1976) Contemporary Research in International Relations: A Perspective

and a Critical Appraisal. New York: Free Press.

Downloaded from jcr.sagepub.com at MCMASTER UNIV LIBRARY on January 8, 2015

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Contemporary Southeast AsiaDocument21 pagesInstitute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Contemporary Southeast AsiaMonsieur HitlurrrNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- PreviewpdfDocument35 pagesPreviewpdfMonsieur HitlurrrNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Royal Institute of International Affairs, Wiley International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)Document2 pagesRoyal Institute of International Affairs, Wiley International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)Monsieur HitlurrrNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Security Dilemma & Arms Race in Southeast Asian Region Post-Cold War Era Muhammad Arsy Ash ShiddiqyDocument14 pagesSecurity Dilemma & Arms Race in Southeast Asian Region Post-Cold War Era Muhammad Arsy Ash ShiddiqyMonsieur HitlurrrNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Al-Mawla Files: The Jihadi Threat To IndonesiaDocument48 pagesThe Al-Mawla Files: The Jihadi Threat To IndonesiaFelix VentourasNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Once A Gun Runner The Efraim Diveroli MemoirDocument311 pagesOnce A Gun Runner The Efraim Diveroli MemoirhertuyoknaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Fighter HackDocument2 pagesThe Fighter HackLucas AlexanderNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Legendary Tools - NobilityDocument13 pagesLegendary Tools - NobilityshittyshitNo ratings yet

- Excretory System NotesDocument17 pagesExcretory System Notesyugaldavanum2008No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- History CH 3 Nazism and The Rise of HitlerDocument32 pagesHistory CH 3 Nazism and The Rise of Hitlerramanpratap712No ratings yet

- Module 1 NSTP 2Document8 pagesModule 1 NSTP 2Charis RebanalNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Full Download Ebook PDF Management Consultancy 2Nd Edition by Joe Omahoney Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full ChapterDocument22 pagesFull Download Ebook PDF Management Consultancy 2Nd Edition by Joe Omahoney Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full Chapterjames.conner294100% (32)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Anders LassenDocument12 pagesAnders LassenClaus Jørgen PetersenNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Thesis Statement Armenian GenocideDocument4 pagesThesis Statement Armenian GenocideDoMyCollegePaperUK100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Fire Emblem 5th EditionDocument18 pagesFire Emblem 5th EditionAlisson SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Manila Studies-5 PDFDocument2 pagesManila Studies-5 PDFJung Rae JaeNo ratings yet

- A Farewell To Arms: (Ernest Hemingway)Document12 pagesA Farewell To Arms: (Ernest Hemingway)Kristine Lyka CaboteNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- City-States-Army-List-V2-September-Update-Web (18 Sep 2023)Document28 pagesCity-States-Army-List-V2-September-Update-Web (18 Sep 2023)dpoet1No ratings yet

- Ravenfeast Points Calculator v1Document15 pagesRavenfeast Points Calculator v1Joshua RaincloudNo ratings yet

- U-Boat Archive - U-Boat KTB - U-995 8th War PatrolDocument26 pagesU-Boat Archive - U-Boat KTB - U-995 8th War PatrolUnai GomezNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Key Aspects of Innovation in Defence SectorDocument9 pagesKey Aspects of Innovation in Defence SectorAbhinav MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Spanish Civil WarDocument8 pagesDissertation Spanish Civil WarBuyPapersOnlineSingapore100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Leader Board Tournament by Bgbei Pot 1 Nama Tim M1 Kill M2 Kill TotalDocument8 pagesLeader Board Tournament by Bgbei Pot 1 Nama Tim M1 Kill M2 Kill TotalPecinta Bela diriNo ratings yet

- TMNT Mutant MayhemDocument115 pagesTMNT Mutant MayhemChristiaan BothmaNo ratings yet

- UNIFORMDocument463 pagesUNIFORMMOHD FADHLI BIN SUPARDI MoeNo ratings yet

- 86 EIGHTY SIX Vol 5 (014 250)Document237 pages86 EIGHTY SIX Vol 5 (014 250)Mateus de Jesus AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- GRE BarronsDocument232 pagesGRE BarronshemantNo ratings yet

- Battletech - MechWarrior Personnel File - SteinerDocument13 pagesBattletech - MechWarrior Personnel File - SteinerElodious0150% (2)

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesEizen DivinagraciaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Principles of War: A Translation From The Japanese: by Dr. Joseph WestDocument129 pagesPrinciples of War: A Translation From The Japanese: by Dr. Joseph WestRogelio versozaNo ratings yet

- The Spire Issue 0Document27 pagesThe Spire Issue 0BobleeSwagger1250% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 1 - FoomDocument20 pages1 - FoomCayce Watson100% (1)