Professional Documents

Culture Documents

STSE by AJCReboa Unit 1

Uploaded by

Bethy MendozaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

STSE by AJCReboa Unit 1

Uploaded by

Bethy MendozaCopyright:

Available Formats

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

SCIENCE,

TECHNOLOGY, SOCIETY,

AND THE ENVIRONMENT

(STSE)

Author:

Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Department of Biology, College of Science

Polytechnic University of the Philippines

NOTE: This instructional module can be used only by intended students as it is for academic

purposes only. This module cannot be altered, rewritten, adapted, duplicated, reproduce, or used

in any way for any commercial purposes and activities. This module is an intellectual property of

the author and protected by copyrights laws.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 1 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

UNIT 1

THE PHILOSOPHICAL,

HISTORICAL, AND

SOCIAL BASES OF SCIENCE

Page

Part 1 – Understanding Science and its Limitation …………………… 03

Part 2 – Science as a System of Knowledge ……………………………. 14

Part 3 – Human Behavior and the Development of Society …………... 33

Part 4 – Human Society as the Development of Science ………………. 52

Image Sources ……………………………………………………………. 69

References & Further Readings ………………………………………... 76

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 2 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

PART 1 – Understanding Science and its Limitation

Introduction

Science, Technology, Society and Environment or STES is an interdisciplinary approach of

science education aiming to teach the students and the public about understanding progress of

human knowledge particularly of science and technology, and to analyze its role in shaping human

society through social, economic and environmental aspects. Initially came from advocacy and

academic movements of different stakeholders and sectors of science education, STES have

evolved to become a full course in universities and educational institutions, aiming to boost

curiosity, to promote critical analysis, and to inspire social participation to students and even the

masses (Mansour, 2009; Aikenhead, 2003; Pedretti, 2005).

From these disciplines, numerous concepts, theories and ideologies have risen: great discoveries

and novel inventions were produced and enjoyed by the society leading to ease of burden of work,

higher quality of life, and economic development (Rescher, 1999). Nonetheless, numerous studies

and evidences about the drawbacks and consequences produced by the advancement of scientific

knowledge, noting that humans have reaped the benefits of science yet with great implications and

repercussions against the society, environment. Thereby, these have stirred public interest in

science, pondering with different socioeconomic, sociopolitical and moral issues that the society

bears as today’s realities and problems (Feyerabend, 1978), such as climate change, energy crises,

decline of biodiversity, genetic engineering, social inequality, overpopulation, so on and so forth.

It is a general objective of STSE to promote scientific knowledge and literacy to the public. Thus,

for us to understand the relevance and implication of science and technology to ourselves, and the

environment, STES requires some background on basic sciences, social sciences, to history,

humanities and philosophy (Mansor, 2009; Savaget and Acero, 2017; Lovbrand et al., 2010).

Likewise, as part of the academic curriculum STSE hopes that the people receiving its education

must be able to (Aikenhead, 2003; Pedretti, 2005):

Widen their views and perspectives about science and technology and its impact to the

society and vice versa;

Nurture ideas and values necessary to analyze issues and construct pertinent conclusions

which can be used for decision-making; and,

Develop sense of responsibility and accountability to every action and decision made.

In this lesson we are going to characterize and discuss science together with its relation to other

discipline of knowledge. We are to explore and analyze the subtleties of science, to comprehend

the role of philosophy and human behavior in the deeper understanding of modern sciences,

nevertheless also to discuss some of its limitation as a discipline and its implication which we can

use to explain science part in directing the development of the human civilization.

Knowledge and Modern Science

Knowledge have a more general reference than science such that knowledge encompasses

anything from objects, events, occurrences, work, endeavor, information, to concrete and abstract

ideas, that consciously we can be aware of, acquainted to, or understood about (Boghossian, 2006).

Knowledge is generally attained through involvement of mental and cognitive processing, with

experience, perception, and learning (Larsen et al. 2013); so, in the succeeding chapters, we will

devote sometime discussing subtleties of human knowledge. On the other hand, modern science

as defined today in the 21st century, is a well-defined accumulation and organization of human

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 3 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

knowledge achieved through a systematic and methodological process called as scientific method

(Andersen and Hepburn, 2016; Heilbron, 2003). In this current view of science, knowledge

produced with this method is distinctly classified as scientific to separate it from other forms of

knowledge which hasn’t generally undergoes the process of scientific method as non-scientific.

Thus, modern scientists and proponents of modern science can test a concept or idea of knowledge

being scientific or not depends on the how the information or data is gathered and undergoes the

process of scientific method, (Hansson, 2017; Andersen and Hepburn, 2016).

Scientific method identifies scientific knowledge through valid and reliable tests that will

determine ideas or concepts truthfully, logically and rationally describing the actual observations

and occurrences in the Universe. However, many philosophers, scientists and science historians

today still have no exact definition what constitute as scientific method. The scientific method we

are familiar about and commonly taught in many science courses at schools and universities, is

known as the positivist’s scientific method. Some of the key assumptions regarding the nature of

science and positivist approach states that the requisite a scientific knowledge must be (Godfrey-

Smith, 2009; Brody, 1993):

Empirically observable, evidence gathering by utilizing the bodily senses;

Testable or verifiable, meaning that an idea or concept must be able to be tested or

validated and repeated for further verification by other people (repeatability);

Falsifiable meaning that an idea or concept can be challenged or contradicted with an

opposite or negative idea or concept with is also equally can be testable and repeatable;

Repeating and continuous process where scientific knowledge is repeatedly tested,

verified and undergoes further improvement, otherwise totally superseded or discarded

(see Figure 1.1); and,

Objectivity must always be observed using scientific method, which can be more

effectively implemented through cooperation with the scientific community and learned

society through effective and scholarly communication and scientific consensus (Popper,

2002), that scientific knowledge is regularly reviewed, assessed and evaluated (Kornfeld

and Hewitt, 1981).

Logical positivism is a core philosophy engrained in scientific method stating that the science

should be solely based on knowledge that is observable, thus excluding anything that is

unobservable as non-scientific and not part of the mainstream science. These philosophical

assumptions led regarding scientific knowledge (Popper 2002; Godfrey-Smith, 2009) undergoes

the strict step-by-step regimen of scientific method steps as follow:

a) Observation – Scientific observation refers to empirical observation, meaning utilization

of the bodily senses to acquire initial data and information, usually from the environment

by experience or learning. Intuitions and extrasensory perception of knowledge are usually

not considered scientific source of knowledge, except in being studied in psychology

(Klein, 2003; Gianini et al., 1984; Sheehy et al., 2002).

b) Determining the problem – This step refers to the deeper inquiry of knowledge gathered

from observation where questions are framed to guide and direct the flow of the scientific

process. Also, these questions are usually more specific rather than generalized, soliciting

answers that must be more well defined, qualified and quantified (Booth et al., 2008).

c) Formulating hypothesis – Plural form is hypotheses; refers to the construction and

presenting rational and logical concept or idea that tentatively can answer the problem that

is being studied. In scientific research, a good hypothesis is a tentative answer to the

research question which directs the research process to certainty, simplicity, and testability

of the concepts involved (Schick and Vaughn, 2002).

d) Testing hypothesis - Gathering evidences and information in this step is carefully

performed either by experimentation or observation that can prove or rebut the hypothesis

or arrive to other results (Wilson, 1998). It is crucial at this stage to delve at the possible

existing association particularly correlation and causality behind the subjects being studied

(Aldrich, 1995).

e) Analysis – Offers answer to the problems and arriving to conclusion and generalization of

the knowledge involved in the scientific process. If the results yielded are inconclusive, the

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 4 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

process shall repeat again with further refinement of the testing grounds, reexamination of

the guiding questions and hypothesis for possible revision either partially or fully.

Otherwise, the whole concept will be totally discarded for new ones (Nola and Irzik, 2005).

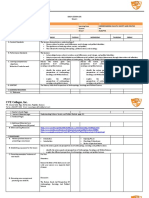

Scientific

Knowledge Scientific

Knowledge

Observation

Determining

Analysis

the Problem

SCIENTIFIC

METHOD

Scientific Scientific

Knowledge Knowledge

Testing Formulating

Hypothesis Hypothesis

Scientific

Knowledge

Figure 1.1 – Modern science distinctly classified a knowledge as scientific if it undergoes the strict

process of scientific method. Scientific method is a continuous, repeating process where at any

step scientific knowledge can be acquired but most of the important scientific contributions are

achieved at the analysis or conclusion step: likewise, scientific knowledge evolves as it is always

reviewed and undergoes further refinement, making the scientific process as iterating and

continuous process.

Subtleties of Modern Science

Modern science is covering many fields and disciplines where many majorities of it are

interdisciplinary, having overlapping interest of studies and engagement (see Figure 1.2). Basic

sciences such as life sciences, physical sciences, social sciences are primarily engaged in studying

underlying fundamental principles that can explain different phenomena and observations in nature

and about human society. Basic sciences employ scientific method through basic research with

the purpose of constructing new scientific theories and concepts or revising and expand existing

ones. While applied sciences, thru applied utilizes understanding of scientific knowledge about

nature to adapt and modify observed phenomena to develop technologies and practical

applications: applied research uses science for purpose of solving practical and realistic world

problems (Arthur, 2009; Rull, 2014).

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 5 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Figure 1.2 – Modern Science comprises of different scientific disciplines and fields and many of

it are have overlapping scope of studies and interest.

Technology must be differentiated from from applied sciences, such that the former refers the

collective enterprise of discoveries, inventions, and knowledge of processes and skills especially

relevant to utility and performance of work; while the latter refers technically to specific

technologies that is a product of scientific research (Wise, 1985). Technology thus is used in the

wider sense of the word, even ancient civilization yielded considerable technological feats without

the actual disciplines of modern sciences, and insomuch that the applied sciences have produced

technologies (Krebs and Krebs, 2003).

Also, life sciences and physical sciences, are classified under natural science since its scientific

knowledge is based on the actual observation of natural phenomena; while sometimes, in some

ways social sciences are classified as part of natural science since human beings are part of nature

and our behavior manifesting individually and collectively are considered natural as part of our

being (Cohen, 1994). Formal systems also called “formal science” are composed of mathematics,

logic information and computational sciences. Knowledge from formal systems are before the

fact or “priori”, independent from reality observed in nature, meaning most of its concepts are

abstract and its evidences are independent from actual observation and experience. Rather its own

proof are the logical process behind the system itself (Thompson, 2007; Bunge, 1998; Carnap,

1991). Here below are the general scope of study by these sciences:

Table 1.1 – Different branches of sciences and each quest of knowledge according to their

respective fields and interests.

Life Sciences - Study life, its nature, origin and development and how possible for

it to exist on Earth

- Study different life forms, their characteristics, habitat, and means

of identifying, naming and classifying them

- Understand our own human body and its functions together with

our relationship with other living things

- Interaction of living things with other living things, under the

influence of non-living (abiotic) factors

-

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 6 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Physical Sciences - Understand and predict physical events, processes, and phenomena

observed on Earth and the Universe

- Understand fundamental physical concepts about as matter,

energy, motion, physical and chemical reactions,

electromagnetism, gravity, radioactivity, classical and quantum

mechanics

-

Social Sciences - Describe and explain human behavior and consciousness

- describe and explain development and attributes of social

interactions and institutions, and progress of civilization and

humanity

- Study, compile and preserve knowledge and historical information

for the future

-

Formal Systems - Understand and utilize numbers, mathematical operations, logical

processes and formal languages which can also be useful in qualify

and quantify phenomena in nature

- Develop comprehensive paradigms and faculties for facilitation,

processing and transferring of data and information

-

Applied Sciences - Utilize and develop theoretical knowledge to purposive,

meaningful, and practical application and development of

technologies needed by human beings

Benefits of Science

Theoretical science helps us study and construct ideas and concepts as basis of scientific theories

which can explain things, events, and phenomena thus able for us to provide prediction of these

occurrence with precision and accuracy. With theoretical sciences, these theories are further

developed and utilized by applied science for purposive, meaningful and practical use.

Subsequently, the scientific knowledge is established and improved thus shall provide wide range

these related concepts of knowledge called paradigms that will be the basis of respective fields of

science and their allied disciplines in pursuing other endeavors and quest to knowledge (Kuhn and

Hacking, 2012).

Table 1.2 – Some of the greatest contributions to mankind by the modern science.

Life Microbiological basis of infectious diseases (germ theory, Koch postulates)

Sciences Discovery of cell and the concept of cell theory stating that the simplest form

of life is the cell and cell came from preexisting cells

Discovery of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid) as

molecules containing genetic information

Understanding of anatomy and physiology leading to improvement of

different fields of medicine (vaccination, antibiotics, chemotherapy and drugs

discovery)

Central dogma of Molecular Biology and its implication on genetic

manipulation (cross-breeding, genetic engineering, mutation and cancer)

Physical Discovery of electricity and magnetism led to how electromagnetic energy

Sciences can be manipulated for general use such as light energy, radio waves

propagation for telecommunication and electrical current to transmit large

amount of electricity for general use

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 7 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Understanding of classical mechanics and thermodynamics principles led to

invention of efficient machines and equipment which can ease the burden of

work (steam and diesel engines, dynamos etc.)

Theory of relativity gives us the view of matter, energy, time, space and

gravity at macroscopic to cosmological scale, leading us to develop satellite

technology (global positioning systems (GPS) and telecommunication

satellites)

Quantum mechanics led us to deeper understanding of matter and energy at

microscopic scale of sub-atomic level, giving us means to explore

applications of electronics, thermonuclear energy of fission and fusion nuclear

reactions, semiconductors, communication and computational systems

Social Improvement of economics, governance and education systems by laying

Sciences down theoretical and practical framework for the feasible, sustainable and

democratic approach on social problems and challenges (market systems,

government system, academic curriculums)

Theories that precisely describes the phenomena of social behavior in humans

can effectively guide policy makers improve policy-making process to

formulate social planning programs applicable to the need of the society

(socioeconomic planning, social works and development)

Understanding of the beginning and development of human society (e.g.

anthropology, archaeology, sociology, history)

Preservation and transfer of human knowledge from generation to generation

(e.g. sociology, culture, tradition and language studies, history)

Formal Mathematical and statistical symbols and operations, including logical

Systems processes and other types of formal languages are used as tools and models

aiding basic and applied research, engineering, computer programming and

automation

Processors, database and data repository to manage big amounts of data and

information (internet servers, world wide web, fiber optics and satellite

telecommunication)

Applied Telecommunication

Sciences Medicine and Genetic Engineering

Engineering and architecture

Robotics and artificial intelligence (AI)

Nanotechnology

Limitations of Science

Human knowledge is essentially differentiated by modern science as either scientific or non-

scientific. Scientific knowledge is the product of the elaborate process of scientific method. Non-

science is considered a separate body of knowledge as it cannot be falsified or reputed by science.

Thus, most of the science practitioners accept scientific method by as the most rational and

objective way of gathering scientific knowledge. However even of today, no consensus was agreed

by philosophers of science about the general logical and epistemological basis of scientific method

and science itself. Philosophers of science have offered different philosophical notions about

science that usually don’t agree with each other. Philosophy of science is a higher study of nature

of science aiming to answer fundamental questions like what constitutes science and the

qualification of scientific method in determining what science must be. Philosophical assumptions

like logical positivism has endured in modern science’s empiricism of treating scientific

knowledge, leading to criticism of the most well-known and influential science philosopher like

Karl Popper, Paul Feyerabend, Thomas Kuhn.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 8 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Karl Popper criticized that scientific theories aren’t product of empirical observation nor that the

correctness of those theories must be verified by these observations, also known as empirical

verification. Rather observations made is accorded to be explained by existing theories that

already preoccupies the science researcher; thus, if a correct observation disagrees with the theory

that the latter shall only be put in question and possibly revise (Popper, 2002). In this case, Popper

claimed that these theories can’t be always verified in every case but rather more applicable to be

reputed or falsified base on rational explanation of the occurrence observed; therefore, the

theories appearing insufficient in form are amended or revised to accommodate an explanation for

these new findings. This refers to what he called as empirical falsification in addition to this claim

that sometimes “bold hypotheses” based on existing theories are necessary to be initially claimed

as it will be the guiding knowledge for the whole scientific inquiry, until till it is refuted or falsified

by empirical evidences ((Popper, 2002; Godfrey-Smith, 2003). He added that the most rational

procedure of gaining scientific knowledge is trial-and-error, in which he stated that “boldly

proposing theories; of trying our best to show that these are erroneous; and of accepting them

tentatively if our critical efforts are unsuccessful” (Popper Lecture on 1959, webfiles.uci.edu),

meaning that scientist offers their own conjectures and subjected repeatedly to criticisms based on

empirical evidences, which can either the conjecture refuted or stand as the tested theory therefore

creating scientific knowledge in the process (Hansson, 2017).

With these notions, Popper saw the problem of induction, which hounds many scientific studies

especially experimentation and natural observation studies. Using induction reasoning, the

attributes of a subject is studied, given that most of the time there are only limited number of times

the subject was observed on certain instances, leading to the generalization about the subject

(Henderson, 2019). The logical dilemma then is formed that the findings may mistakenly led the

researcher to hasty infer about the subject even though there is a possibility that there would be

cases of exemptions not applicable to the whole population of the subject, or inadequately

represented by a limited number of samples and observation to arrive on a valid generalization

(see Figure 1.3). Another problem of induction is the presumption that a phenomenon that will

happen in the future should be observed as invariant and always the same as it was happened in

the past. David Hume postulated an unprovable assumption that the laws of physics remains the

same from the past and even to the future, applicable in any part of the Universe, called the

doctrine of uniformity (Hume and Beauchamp, 2000). Nevertheless, this principle even though

cannot be verified nor falsified is accepted as one of the philosophical foundations of modern

science.

Figure 1.3 – The Problem of Induction Reasoning. Through repeated observation and experience

of sun rising in the east, it is a valid inference by inductive reasoning that the sun always rises in

the east. However, the allegory of the “blind men and the elephant” provides us about the pitfalls

of inductive reasoning, as if limited observation and insufficient evidence, one can incorrectly infer

leading to hasty generalization.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 9 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

On the other hand, the problem of demarcation as explained by Popper exposes the lack of

consensus regarding a criterion of determining scientific knowledge from non-scientific

knowledge. Popper offered a solution such that science, its theories and concepts is proven not by

verification but by process refutation or falsification based on existing empirical evidences, while

non-science offers knowledge that are mostly unfalsifiable due to limited empirical means of

testing those concepts. However, Feyerabend and Kuhn criticize Popper that the demarcation

issues between science and non-science is not significant because the scientific method inherently

poses limitation due to logical constraint as the consequence of its framework; and scientific

method essentially relies on philosophical assumptions that can’t be explain nor proven by science

itself. Yet, they reiterated that the rationality and objectivity of the science proponents and public

differs with respect to individual perspective and existing knowledge in the study.

Paul Feyerabend and Thomas Kuhn delved on the analysis of perennial philosophical problems

about the comparability of existing scientific theories and epistemological basis of scientific

method (Feyerabend, 1987; Kuhn and Hacking, 2012; Preston, 2016). The commensurability of

scientific theories depends on common, well-defined criteria and context of comparison; meaning

that for scientists to directly compare rival theories to determine their validity and realness, there

must be a “standard language” composed of “semantic” and “taxonomic” characterization that can

directly qualify or quantify the comparability of these theories (Feyerabend, 1981; Kuhn and

Hacking, 2012). Feyerabend and Kuhn both agree that theories and knowledge produced by

sciences for many years are mostly incommensurable to each other due to differences and

intricacies of paradigms involved: basically, questioning how these constituting concepts of these

paradigms were formed and assembled, and how these concepts were received and viewed

objectively and rationally to an agreeable degree as standard so these theories and knowledge can

be compared squarely and of equal footing. Feyerabend also reiterated that the concept of empirical

falsifiability will not be significant at this point of incommensurability since empirical evidences

are viewed in the light of existing theories or the researchers conjectures which can further lessen

the commensurability (Feyerabend, 1985; Feyerabend, 1981); thus, he concluded that no theory

even how scientific and convincing, is entirely agrees with all pertinent facts being studied

(Lakatos et al. 1999; Feyerabend, 1987).

Kuhn pointed out that many scientific theories are incommensurable, that each theory offers

different portrayal and explanation of phenomena in nature, and many of these rival theories aren’t

congruent nonetheless largely in disagreement to each other. He reiterated that the scientific

process naturally can never be fully objective and rational but rather also affected by the personal

perspective and presumption that directs the thinking of the scientists or researcher (Kuhn and

Hacking, 2012; Kuhn, 1977). With these, the theories constituting the paradigms, can contain

diverse concepts and pieces of knowledge that even though they are similar in context and field of

study, will vary from scientist to other scientist, in as much that these paradigms offer incompatible

notions of understanding about the subject of knowledge. Therefore, he defined scientific

paradigm as to scientific knowledge and “universally recognized achievements” that provides

“model problems and solutions” guiding scientists and researchers for a time until changed (Bird,

2018; Kuhn and Hacking, 2012; Kuhn, 1970).

Consequently, scientific knowledge thus advances according to existing scientific paradigms

which lays the methodologies, theoretical and conceptual background of the scientific process

itself, and not by comparing which is the better paradigm. Progress of knowledge takes place after

the existing paradigms were tested insufficient to explain the observation or as failure to predict

the occurrence of phenomena being studied (Nickles, 2017; Niiniluoto, 2015). Repeated

occurrence of serious incongruities in observational evidences causes the existing paradigms to

loss power of being a rational account of the phenomena being studied. Thus, a science practitioner

is compelled to one’s own perspective of objectivity and personal rationality to revise the old

paradigms, even to the point to discard the old and to propose a new theory that will accommodate

the new findings; these significant changes in the paradigm used in the scientific process leading

to novel discoveries and contribution to scientific knowledge: then Kuhn called the paradigm

shift, fueling scientific revolutions (Kuhn and Hacking, 2012; Kuhn, 1970).

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 10 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

As an example, the inadequacy of Aristotelian and Newtonian mechanics in describing the laws

governing the Universe were highlighted by Feyerabend that these theories were universally

accepted and valid on their respective time, until 20th century where they were superseded by

Einstein special and general theory of relativity because of the latter can accommodate the old data

and even more the anomalous data about the shift in the orbit of Mercury around the Sun and the

bending of light by massive in which the former theories failed to provide rational explanation and

prediction of the said occurrence (Feyerabend, 1993). Surprisingly, the Einstein’s theory of

relativity during his time apparently appears not so useful, yet controversial and revolutionary that

it rocked the established theory of physics that time, and most of its postulates and concepts were

initially unfalsifiable and unverifiable but rather based on the “thought experiment”, or mental

visualization of the phenomena; since the existing paradigm at that time is not adequate to perform

enough empirical observation and practical testing of the theory (Brush, 1999).

Thus, Kuhn and Feyerabend both agree that the scientific method has its limitation and thus can

never be the only universal approach in explaining nature, nor it can be better than non-scientific

theories and concepts in explaining many phenomena and subjects (Kuhn, 1977). Somewhat, they

pointed out that science being established with its inseparable logical processes, inevitably is also

a social process influenced by the science practitioners and the public receiving science.

Feyerabend nevertheless postulated the tendency of modern science to lose its philosophical

grounds and therefore to be succumb to its dogmatic use of scientific method due to its limitations

(Lakatos et al., 1999). At the epistemological basis, he added that due to logical constraint about

the nature of science, the scientific method doesn’t have the exclusive grounds on determining the

truth, nor it is consistent in providing theories that will describe the entirety of the Universe. Kuhn

and Feyerabend, reiterates the role of social processes and non-scientific body of knowledge as

another source of knowledge which cannot be provided by modern science, in understanding and

inquiring some of the most enduring questions about life, reality, beauty, morality and spirituality

such as the following:

1) What is good and what is bad? (Ethics). Science and scientific method on itself don’t have

its own heuristic of morality, thus evaluate scientific knowledge based on the ethical notion

of “good” and “bad”. Scientific process employs logic, rationality and objectivity in

analysis to arrive on valid conclusions according to facts and empirical evidences (Teller,

1998; Lutz and Lenman, 2018)

2) What is beauty and beautifulness? (Aesthetics). Even thought the appreciation of beauty

employs empirical observation meaning use of the bodily senses, science has no direct

means to evaluate the values involved in appreciation of what is beauty and ‘beautiful’

science concepts. However, it is profound that science touches the curiosity and passion of

science practitioners thereby expressing their personal fascination and attraction to their

respective scientific endeavor (Engler, 1994). Also, today neuroscientists are currently

active in finding the neurobiological roots of sensation and aesthetic experiences

(Shimamura, 2011).

3) What is knowledge and essence of knowledge? (Epistemology). Science aims for the quest

of knowledge and truth. It is written in history that modern science traced itself from its

philosophical roots. Also, science holds to many philosophical concepts that can not be

explained by science itself nor why science uses these concepts: yet it is evident that

knowledge do progresses (Kuhn and Hacking, 2012; Lakatos et al., 1999). It is still a debate

on many philosophers of science about what constitutes science as science, and elucidate

fundamental concepts describing scientific knowledge.

4) What is reality or what is real? Is the human mind can perceive real things or the product

of our mental and cognitive faculties affects our perception of reality itself?

(Metaphysics). Metaphysics of science aims to answer the reality of laws of nature, to

expound the scientific concepts cause, effect and relationship to other concepts based on

reality of these concepts, including the effect of our perception and existence to the

understanding of these concepts (Gohner and Schrenk, iep.utm.edu)

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 11 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

5) What is the purpose of life on the Universe? Are there other life forms out there?

(Cosmology).

6) Why are we here? What is our existence? Is there a Supreme Being? (Religion).

7) What constitutes a “good” culture? What is legality of law? Is a concept or idea that it not

empirically observable, testable, verifiable, and falsifiable (quantum entanglement,

relativistic implications, dark matter, dark energy, fate of the Universe, unobservable

Universe, mathematics, God, spirits, human consciousness, emotions, etc.) not science? If

they are reality or real prior knowledge, then why are they cannot be described as Science?

Even today, there are many realities, concepts and ideas that cannot be explained or understand on

the scientific context, like the complexities of human behavior, non-scientific knowledge being

studied by the disciplines of humanities, religion, and philosophy. Thus, it is a necessity to

understand the difference between scientific knowledge and non-scientific knowledge, base on the

limitation of science as a body of knowledge.

STSE as Science Education

In face of digital information, globalization, cultural mixing, environmental degradation,

socioeconomic and sociopolitical challenges, it is a must for us to study science education to

increase understanding thus social involvement to address societal problems through science and

technology (Mansour, 2009; Pedretti, 2005; Aikenhead, 2003; Longino, 2016). These include

some general approach on how we can study science and technology:

Philosophical – This perspective of understanding the aspects science and technology is

explained in terms of philosophical and logical background of sciences: an inquiry about

the knowledgeableness, meaningfulness, rationality, believability of sciences to our

perspectives as recipient of it;

Historical – The historicity of science can never be underestimated, since the

chronological and narrative background of the development of society and human

knowledge leading to advancement of science and technology can give us a light on how

the progress of human civilization and its influences have contributed to its change; and,

Social – A societal and practical approach giving us an applied, issue-based and realistic

point-of-view about science and technology: relevant and timely issues which has

significant effect on the society and human lives.

Therefore, it is STSE main role in educating students and winning public interest regarding the

benefits and limitations of modern science (Aikenhead, 2005). The fruits of scientific knowledge

have greatly shaped the social institutions of the society and has fashioned many disciplines

directing many of human endeavors such as the advancement of technology and improvement of

quality of life, nevertheless its drawbacks and repercussions (Jasanoff, 2003). It is crucial to know

that science have evolved dramatically from the beginning of mankind until today due to it being

highly tied to the development of the human society and civilization (Kuhn and Hacking, 2012);

and to understand it is we must trace back the philosophical, historical and social background of

science.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 12 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

REALITY AND APPLICATION

“Scientia potentia est”

The whole world was awed of nuclear technology, after the United States dropped the atomic bomb

at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan on 1945, ending the World War II. It was the first and only

time that nuclear energy was used as a weapon in war, against a belligerent nation, and since then

nuclear weapons were developed by countries like Russia then Soviet Union, France, China, and

the United Kingdom. Also, India, Pakistan and Israel have made to join the nuclear club due to

their respective interest.

Nuclear physics proves to be a powerhouse of knowledge providing great theoretical details of

nuclear fission and nuclear fusion, caveats of technological marvels from Becquerel and Curies’

discovery of radioactivity until Teller and Ulam had solved their nuclear reaction problems for the

design of a thermonuclearly effective hydrogen bomb. Nevertheless, it provided us more useful

applications of nuclear fervor: smoke detectors, x-ray radiographs, radioisotopes for radiation

therapy, gamma ray’s food sterilizers, and nuclear powerplants are one of the few examples of

peaceful nuclear energy in action.

Aside from nuclear energy, can you name other scientific marvels with very promising

contributions to mankind, yet with dreadful consequences?

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 13 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

PART 2 – Science as a System of Knowledge

Introduction

Human knowledge is essentially differentiated by modern science as either scientific or non-

scientific. Scientific knowledge is the product of the elaborate process of scientific method which

is generally accepted by science practitioners as the most rational and objective approach in

gathering scientific knowledge. These makes non-scientific knowledge as distinct body of

knowledge as many of its concepts and idea cannot be verified, falsified or reputed by known

scientific processes; thus, these pose some fundamental nature of science. Philosophy of science

aims to elucidate the nature of science and limitation of science as body of knowledge. Even today,

there are many realities, concepts and ideas that cannot be explained or understand on the scientific

context, like the complexities of human behavior, non-scientific knowledge being studied by the

disciplines of humanities, religion philosophy. Nevertheless, these defines modern science as a

systematic body of knowledge which are tested through the processes of scientific method

(Wilson, 1998; Heilbron, 2003). Nevertheless, it is a paramount consideration to understand the

fact that modern science covers interdisciplinary fields and disciplines from life sciences, physical

sciences, social sciences, formal systems, applied sciences. Technology meanwhile refers not only

about the set of modern disciplines, skills, and inventions, but also to those even existed during

the ancient times, from humans societies and civilization that have yielded considerable vast

knowledge and technological feats (Krebs and Krebs, 2003).

Figure 2.1 - Modern Science is a systematic body of knowledge comprises of different scientific

disciplines and fields and many of it are have related concepts and ideas, and overlapping scope

of studies and interest.

In this lesson we are going to delve in the fundamental understanding of the observed realities,

concepts and ideas in our daily lives, and how it forms the systematic body of knowledge which

we known today as modern science. We are to explore the intricacies of scientific knowledge, to

comprehend that the observation of different occurrences and phenomena in daily life of human

beings molds our thinking; and, realize the relationship of our perception and thinking about the

about ourselves and our surroundings contributes to a greater system of knowledge.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 14 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Understanding a “system”

“System” is a common byword of the masses, used in different connotations and contexts in the

society such as scientists organizing their theories, public administrators and politicians for policy-

making, economic and business enterprises such as stock exchange and banking system, and even

from daily affairs like people falling in line at the cashier counter of a department store, or traffic

scheme implemented on national highways and roads. Also, “system” is attached to well-known

catchwords in the society such as mathematical systems, educational systems, information

systems, car’s transmission system, social security system, and the solar system. Nevertheless of

the usage, it is worth noting that there is a common ideas and concepts about “system” such that it

denotes relationship, order, arrangement, causality and reality; also, it denotes parts forming a

whole, or whole dissected into parts, or components that are interconnected to each other. Yet it is

also worth to notice that “systems” even though are defined and used interchangeably on

differently in natural sciences (thermodynamics, chemistry, ecology, etc.), social sciences

(geography, sociology, psychology, etc.), formal sciences (mathematics, logic, computer

languages, etc.) and humanities (philosophy, arts, history etc.).

Though used accordingly different by many disciplines of knowledge, generally "system" is

defined as an arranged group of things, occurrences, perception and/or thinking that are reliantly

connected and reliant to each other, which generally holds to an actual observation, pattern,

orientation, concept, and/or idea: as this was defined by Bertalanffy (1969) and Miller (1978).

Thus a “system” explicitly and implicitly present goals and objectives to be attained, which will

make the “system” itself sensical and useful (Miller and Miller, 1992; Miller and Miller, 1993):

thus, the basic assumptions under the systems theory, as the current mainstream theory which

explain the philosophical and sociological foundations of “system” (Bertalanffy, 1950;

Bertalanffy, 1969; Miller, 1978; Kauffman, 1995). Namely, the main features of a “systems” are

stated below:

Existing interrelationship between the parts of the system must exist, meaning the

components are able to rationally and logically fit to each other;

Possesses interdependence between the parts of the system with the ability for each part to

describe or support each other with respect to the whole “system” itself;

The framework, either theoretical or realistic, meaning to the substance and essence of the

association of the parts forming the whole as a system, precedes the importance of the

parts; and,

A system has a structure, order and arrangement of its components making it logical and

useful.

Subtleties of a “System”

A system is usually composed of a smaller component system called subsystem. A subsystem on

itself is a system comprised of more basic components. Also, a system is distinct on its own such

that it possesses a delineation of its own elements divided from those which are separated or not

congruent to it, thus having an interface from the outside. The outside of the system is generally

called the surrounding such the interface that delineate or divide is called boundary. The boundary

can be discrete or continuous with the surroundings, thus a system can be classified as open, closed,

and isolated. An open system allows in and out of matter, energy, and information with its

surroundings, while a closed system allows exchange of energy but not matter, thus also

information. In an isolated system, matter and energy cannot pass in nor the ones inside to go out,

thus very limited to nil information about the system. Still, a “system” is an intellectual framework

created by us humans to picture-out, describe, and study our understanding about ourselves and

the environment, influenced by our perception of the realities, and our worldviews about different

issues in life, thus natural and man-made systems must be delineated. Conversely, nature is

defined as the totality of all things which includes all matter, energy, processes, and information

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 15 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

in the Universe, including us humans. However, it is our common conception to draw boundary

between ourselves, the surroundings and nature.

Table 2.1 – Some of the most important systems that have much concern and interest to

humans (Bertalanffy, 1969; Miller, 1978; Kauffman, 1995).

These refers to real, concrete, and physical objects, occurrences, and phenomena

in the known physical Universe. Most of the elements and components of these

Physical

systems are the known physical stuffs comprising of matter, energy, space, and

systems

time which are the general subjects of the fields of natural sciences from

physical sciences to and life sciences.

These are systems comprising of universally logical abstract entities, rules, and

Formal concepts in which humans have been expressing and studying using arbitrary

systems sets of symbols and signs arbitrarily called “formal language”. These generally

involved of logical, mathematical, and probability mechanisms.

Socio-cultural systems are composed of anthropogenic components primarily

Socio- attributed due to inherent human attributes (both biological and behavioral) and

cultural other resultant factors such as social order, linguistics, cultures, norms, values,

systems and world views. Many disciplines are concerned on the study of socio-cultural

systems, from social sciences to humanities.

Conceptual systems are composed of concepts and ideas which denote either the

abstract and/or physical entities. A conceptual system depends on the observer

Conceptual that was performing an observation and conceptualization of a

systems framework/model of things and events of concern and being studied with.

Logical, mathematical, or both can be used as to define and describe the system

through use of a language.

Artificial systems are usually human-made attribution of relationship and

Artificial connection of things which are not naturally observed in nature. Example of

systems these are traffic scheme systems, Linnaean taxonomy classification, and Dewey

library system.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 16 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Figure 2.1 – A “system” is an intellectual framework created by us humans to picture-out,

describe, and study our understanding about ourselves and the environment. A system is a point

of interest/study, consist of parts (subsystems), working together as a whole or a large unit.

On the other hand, it is very important to understand that any system uses the most fundamental

concepts of human knowledge, which is philosophy (Stenlund, 1990; Friedenberg and Silverman,

2016). To reiterate this philosophical nature of a system, the use of languages and semantics is

very crucial in understanding systems; such language is a system itself comprising of logical,

mental/cognitive and social constructs that supports the structure and facilitate the mechanisms of

the system: primarily syntax and semantics play as a crucial scaffolding of languages, such as the

former provides rules, order and notation (signs and symbols), while the latter deals about the

meanings and interpretations of languages and its modalities. Languages are classified as the

following: natural languages, meaning those languages that were commonly expressed, spoken,

and written, by humans such as Filipino, English, Chinese, and Sign languages; formal languages,

notations and processes of logic and mathematics; and, artificial languages which were used in

computer programming and information technology.

Aside from its components, a system can still be further analyzed based on its spatial (space) and

temporal (time) factors, meaning a system can still be further characterize it either dynamic

(changing or varying) or static (constant or unchanging) system. Thus, it is also crucial to

understand that the systems can also serve as mechanism or process of change primarily in the

processing of information so knowledge; and these provide the basic concept of theoretical and

conceptual framework used in research methodologies and experimental protocols (Seibt, 2018;

Williams, 1985; Hassan et al., 2018).

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 17 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Figure 2.1 – A “system” is an intellectual framework with an input, process and output (IPO)

modalities. Here a scientific method is an excellent example of how a system changes through

time and different landscape.

Sciences as Systems of Concepts about Nature, Society, and Knowledge

In the beginning 13.75 billion years ago that the first atoms of hydrogen, helium, lithium, and other

chemical elements of lighter nucleus appeared in our Universe, immediately after energy, time

and space were created. Energy had been undergoing further process of differentiation for some

time to form matter, so the first atoms and the elements, and the fundamental interactions in

nature which is until to the future (until today, this moment that you are reading this book) shall

determine the laws that governs the organization, order of nature and ultimately the fate of our

known Universe (see figure below). Few billion years after the start of creation of the Universe,

the first stars shone having started nuclear reaction at their core, thus forming heavier chemical

elements like iron, nickel and gold. Great masses of matter like gases and dusts were pulled to

themselves and then to apart due to effects of gravitational force and dark energy working together,

forming intricates of celestial structures from colossal super-clusters of galaxies to small star

systems.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 18 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Table 2.2 – Some of the most important phenomena observed by human beings, with the field of

sciences and scientific concepts that covers the interest of study.

Natural Field of Sciences and Important

Order in Nature Scientific Concepts

Physical Sciences

Strong Nuclear Force or “Strong Force” - Atomic stability

One of the fundamental interactions of nature, - Nuclear Fusion and Fission

this attractive force is necessary to hold the - Quantum Mechanics

particles that forms the nucleons (protons and - String Theory (hypothetically)

neutrons) and binds them together in the nucleus

of an atom, thus atoms and elements are formed. Applied Sciences

Formal Sciences

Weak Nuclear Force or “Weak Force” Physical Sciences

This repulsion force is necessary to the stability - Atomic stability

of the nucleus of an atom. This force is necessary - Radioactivity and Nuclear Reactions

to split unstable heavy atoms to form more stable - Mechanics

lighter elements. - String Theory (hypothetically)

Physical Sciences

- Classical Mechanics

- Quantum Mechanics

- Chemistry

Electromagnetic Force

This force either attractive or repulsive, is Life Sciences

essential to some of the most common important - Life

physical phenomena to man such as light, - Biochemistry

electricity, magnetism and chemical reactions. - Metabolism

- Photosynthesis

Applied Sciences

Formal Sciences

Physical Sciences

- Newtons Universal Law of Gravitation

- Theory of Relativity (Special and

Gravitational Force General Relativity)

This attraction force is the effect of the mass of - String Theory (hypothetically to

a matter in time-space dimension. Matter has combine Relativity with Quantum

mass and occupy space exerting curvature to Mechanics)

the time-space, causing nearby matter to curve

towards another nearby matter, thus causing Life Sciences

them to attract and hold the two objects to each - Extraterrestrial life (hypothetically)

other (Feynman et al., 1995). - Exobiology/Astrobiology

Applied Sciences

Formal Sciences

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 19 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Dark Energy

Hypothetical explanation in observed Physical Sciences

astronomical phenomena of expansion of the Possibly undiscovered laws of physics

Universe. This energy is thought to be due to yet the only existing paradigm that

the intrinsic property of vacuum of space and explain it is the theory of Relativity

time-space itself expanding, pulling the matter (Special and General Relativity)

in the Universe away from each other. Dark

energy is thought to cause the expansion of the Formal Sciences

Universe. Never been observe directly.

Physical Sciences

Visible Matter or “Ordinary Matter” and its

- Classical Mechanics

counterpart, the Antimatter

- Quantum Mechanics

Also known as “baryonic matter” since this

- Theory of Relativity

matter is essentially made up of atoms which

- Chemistry

nucleus is composed of subatomic particles

“protons” and “neutrons”. There are known 124

Life Sciences

elements known to man and these are

- Biology

essentially made up of atoms. Antimatter are

- Ecology

almost the same with known matter, except it

- Microbiology

has an opposite charge and different quantum

- Biochemistry

properties. In contact, antimatter and matter

- Metabolism

annihilate each other from existence producing

large amount of energy and new particles of

Applied Sciences

matter (Smorra et al., 2017).

Social Sciences

Formal Sciences

Dark Matter or “Invisible Matter”

These are “exotic matter” in which their nature

is still unknown since they don’t emit light nor Physical Sciences

interact with visible matter, but only affected by Possibly undiscovered laws of physics

gravity as calculated from its gravitational yet the only existing paradigm that

effect (as the missing or unaccounted mass explain it is the theory of Relativity

minus total mass of visible matter in a galaxy) (Special and General Relativity)

and unexplained halo effects observed from

telescopic views of galaxies.

Physical Sciences

- Classical Mechanics

- Quantum Mechanics

- Theory of Relativity

- Chemistry

Energy Life Sciences

Is physical concept regarding the ability to - Biology

perform work. Related to energy is power, - Ecology

meaning the amount of work performed in a - Microbiology

given amount of time. - Biochemistry

- Physiology

- Metabolism

Applied Sciences

Social Sciences

Formal Sciences

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 20 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

It was 50000 BCE that humans have fully utilized our physical, biological and psychological

adaptation which led to our species Homo sapiens sapiens survival and flourishing, we have

acquired new type of adaptation based on social interaction and behavioral modernity called

cultural adaptation such as technology, tools, religion, arts, daily subsistence such as food and

water, settlement and rituals (d’Errico and Stringer, 2011; Nowell, 2010). The complexity of

social interactions and culture have evolved due time which also caused the social role of each

member in a community to evolve, leading to the formation of human society. In anthropological

and sociological perspective, human culture exists and evolves due to complex interaction of

factors, producing cultural diversity or multitudes of forms and customs observed in different

societies. Humans have shared experiences, social interactions and communication through a long

and dramatic evolution of human knowledge and our intellect. Nevertheless, the complexity of

the social structure or order, or observable social patterns within a group of humans or between

the groups of humans can be traced on the development of human culture. As we humans realized

our contribution within our group called community, we realized that our social status in the

social structure is defined by our respective functions or role, leading to what will be our identity

in the society (see figure below). Regardless of cultural diversity and environmental differences,

different human cultures have shared a common pattern and similarity in terms of development of

human knowledge and its effect on the advancement of the human society.

Figure 2.2 – The socio-cultural systems of human society and human civilization are such complex

systems, composed and influenced by anthropogenic and environmental factors. We humans are

part of that system and our place is further shaped by the culture and social structure. The system

is such a dynamic one that for only not more than 100000 years ago, we have drastically induced

change on Earth (d’Errico and Stringer, 2011; Nowell, 2010).

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 21 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Generally, humans are conscious, thinking animals with the cognitive faculties to learn and to

make sound reasoning. Thus, humans’ do reason by mentally processing information in an

analytical (scrutinize information to its details) and critical (compare information to other

information) way of thinking, aiming to arrive with a comprehensive and rational idea, concept or

conclusion. We have devised concepts and ideas called paradigms, consisting of methodologies

on how we determine an idea and concept as “knowledgeable” through our information gathering

and reasoning. Also, roughly the same meaning, paradigm is the human perspective or “point-of-

view” regarding knowledge. Sometimes information drawn to the perspective of a philosopher is

not the same with regards to a natural scientist. However, together these constitute the basis of

human understanding where we humans have gained over time, have shared with each other, and

have persisted and changed with us, known as knowledge (Heilbron, 2003; Wilson, 1998). The

main endeavors of human knowledge have emerged to the systems we know today as Philosophy,

Sciences, Religion, Society, Civilization and Humanities.

Figure 2.3 – Human knowledge is a system on its own and, science just play a part on the

systematic body of human knowledge.

Scientific knowledge is the product of the elaborate process of scientific method. Non-science is

considered a separate body of knowledge as it cannot be falsified or reputed by science. Thus,

most of the science practitioners accept scientific method by as the most rational and objective

way of gathering scientific knowledge. Though, no agreement is reached until today about the

fundamental epistemological basis of science; in as much that there many realities and phenomena

in life that cannot be explained nor clarified by modern science. Accordingly, philosophy of

science is a higher study about the nature of science aiming to answer fundamental questions like

what constitutes science and the qualification of scientific method in determining what science

must be.

In this lesson we are going to delve about the nature of knowledge. So, we are about to explore

and analyze the basic principles of philosophy, as the essential framework of scientific processes:

to comprehend the role of philosophy and human behavior in the deeper understanding of modern

sciences, nevertheless will give light to deeper understanding of science.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 22 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Systematic Body of Knowledge

Generally, humans are conscious, thinking animals with the cognitive faculties to learn and to

make sound reasoning. Thus, humans’ do reason by mentally processing information in an

analytical (scrutinize information to its details) and critical (compare information to other

information) way of thinking, aiming to arrive with a comprehensive and rational idea, concept or

conclusion (Ichikawa et al., 2018). Conversely, the basic unit of human knowledge is the mental

faculties of idea and concept, basically attributing characteristics which describes and defines

something real, imaginary or abstract (Margolis and Laurence, 2014; Longino, 2016; Samet,

2008). Example of these is the use of language, the main conveyor of knowledge by humans either

written, oral, or signaled. Visual representation or the actual observation or experience (see Figure

3.1).

Deductive reasoning is inferring that a premise (e.g. claim, conjecture, general statement) is valid

or applicable then the terms that follow (or under) after the premise is similarly valid or applicable

also. Informally known as the “up to bottom logic”, meaning that if an argument or theory is true

then must be the sub-concepts must also be. In other words, general ideas or concepts are used to

explain more specific ideas or concepts; that the general principles explain the reasons behind

special or individual cases. On the other hand, inductive reasoning or “bottom to up logic” is in

the opposite direction of inference compared to deductive reasoning; the premises are the terms of

proofs to arrive to valid conclusion. Meaning specific ideas or concepts are used to explain more

general ideas or concepts; individual or special cases explain to find a more general principle

(Henderson, 2019). Abductive reasoning however is inference of finding simplest idea or concept

among the "the best explanations" that explain an idea or concept of interest, based from an

observation.

APPLE

Apple

Mansanas

Malus pumila

Figure 2.4 - The idea and concept of Idea and Concept of an apple. An idea of an “apple” depends

on our perception and reasoning of attributes or characteristics that defines and delineate and

“apple”. A concept of an “apple” depends on the ideas you are thinking about an “apple”. Apple

can be spoken or written in different forms and languages (upper left), or can be creatively

represented by an illustration (upper middle), or can actual image of an apple (upper right). We

can also identify an “apple” as the fruit, leaves, branches or the tree itself (lower left) depending

on how we relate ideas and concepts with other ideas and concepts. An apple pie (lower right) is

not an apple pie with apples, but is it correct to say that the apple pie is also an apple? On a different

context, “Apple” can be associated with a well-known brand of computer and cellular phone.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 23 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Logic is the branch of philosophy that studies the aspects of reasoning: aiming to arrive at valid

justification, judgement, affirmation or rejection of ideas and concepts we humans understood and

reasoned either deductively, inductively, or abductively about things in nature and life are

systematically and thematically arranged and formed a paradigm or conglomerate of knowledge

either theoretical or practical purpose (Ichikawa et al., 2018; Longino, 2016). With these,

relationship of things in nature can be understood by making representations, simulations and

symbols of ideas and concepts called conceptual models (see Figure 3.2; Margolis et al. 2014;

Craver and Tabery, 2017). Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of

reality, existence and causality of things and what constitute to these fundamental concepts.

Cause Effect

Cause (C) Effect (E) (C) (E)

I II

E3 C4 E9

E12

C9 C8 C1 C2 C6 E7

E10 C3 C5 III

Figure 2.5 - The Causality. The three examples of conceptual model above are the models about

causality, called causal model in which we can understand such that, I) single cause then leads to

single effect, a model showing linear relationship, II) single cause then leads to a single effect

which is also the cause of that effect, a model showing non-linear, cyclic relationship, and III)

many causes leading to many effects affecting it each other or not, a model showing complex

relationship.

With logical reasoning we have developed complex ideas, concepts and their relationships in the

form of hypothesis, theories, justifications, beliefs and values. The way and manner we developed

these ideas and concepts depending on our ability of reasoning and perception on the reality around

us (see Figure 3.3). With these paradigms were made and it is pervasive in the evolution of human

endeavors of civilizations, sciences and humanities that it is also changing or adapting to meet the

needs of the advancement of human knowledge. This significant change in approaches how we

pursue knowledge is paradigm shift. Paradigm shifts then leads to revolutionary changes not only

on the knowledge itself but also to human culture and society, which we see the effects as

innovations (). Different perspectives have created multitudes of different disciplines and

approaches we reasoned and understood knowledge. However, it is notable that these perspectives

or paradigms share basic similarities like reasoning, ideas and concept.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 24 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Figure 2.6 – This conceptual model showing the relationship between reasoning and the level of

knowledge involved.

Epistemology seeks to answer the fundamental questions about the nature of knowledge,

rationality, objectivity and justification (Perla, 2011; Parikh et al., 2017). The under lying

principles regarding the what to be considered as knowledge, the scope and justification of belief

(see Figure 3.4). Philosophy inquires about the aspects of reality, existence, intellect, wisdom,

knowledge, endeavor and beauty.

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 25 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Figure 2.7 – Aristotle is one of the first philosopher more definite in describing knowledge, known

as the tripartite model of knowledge. According to this theory, knowledge is something that can

be justified, true, and believed as indicated JTB in the Venn Diagram. However, some modern

philosophers have proposed the extended tripartite model, meaning JT, TB and JB is also part of

knowledge depending on the logical approach and paradigm of learning. JT means something that

is justified and true, however is not believed; TB is something that can be true and believed but

not justified; and, JB stands for something that can be justified and believed but not true.

Knowledge and the Human Experience

For thousands of years, philosophers are still puzzled about the nature of knowledge and the role

of human intellect in shaping human knowledge dating back from Plato until today. Yet, majority

of philosophers agreed that knowledge depends on our understanding the relationship truths,

beliefs, and our justifications using our intellect. Philosophers generally agree that humans have

been able to develop knowledge that: we humans are naturally conscious and rational animals,

curious of ourselves and the surroundings; we naturally aim to understand reality and our

existence; we naturally aim to understand and achieve what is good, correct, and acceptable;

we “know” or “understand” things for practically utilizing it for a purpose; we since the

prehistoric times have been developing and organizing human knowledge; and we pursue

knowledge because of knowledge itself. Thus, philosophers have offered some of the well-known

philosophical approach on understanding knowledge and have influenced the progress of modern

science (Smith, 2003; Rescher, 1999):

Rationalism. This theory states that the human ability to think and reason is the best of

finding and achieving knowledge either dependent or independent of empirical evidences.

Also, rationalism states that there are concepts and truths that can only be known and

understood through logical and rational thinking without depending on direct experience

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 26 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

or cannot be directly observe by the senses (Markie, 2017). Human knowledge is “fallible”

or can be doubtful, however that fallibility or doubtfulness we are thinking tells us that

undoubtedly, we are really thinking and reasoning. Therefore, knowledge is real and

attainable, and we just need to do is to think, reason again and then acquire knowledge

again (Dea et al., 2017).

Realism. In realism, knowledge approximates the truth and existence of things in this

world. The reality of the things in this world is independent of our mind and how we

perceive and understood those things. The possibility is that our minds can limited by our

perception and understanding of these things in this world. Thus, it is our aim to pursue

learning and studying to arrive with the exactness and completeness of understanding of

the things in the world (Miller, 2016).

Idealism. Idealism tells us that knowledge is naturally the product of our mind, and the

“reality we know” is significantly based on our own thinking and reasoning not only of

actual experience and observation of the “reality” itself (Guyer and Horstmann, 2018).

Idealism also states that there is “a priori”, reason or knowledge independent of experience,

and “a posteriori” meaning reason or knowledge dependent on direct experience by the

senses. Thereby knowledge is also dependent considering the objectivity of our reasoning.

Existentialism. The theory reiterates that the human’s own individual experience and

perspective of the reality is the only meaningful in arriving to knowledge. There is no

definite or standard means of knowing all the knowledge since humans cannot on

themselves will know it all. Knowledge is attained through self’s own effort, freedom and

volition and not necessary influenced by external interferences. Also, it is the aim of man

to exist first then is the essence of life (Crowell, 2017).

Pragmatism. Pragmatism states the main aim of knowledge is of successful utilization.

Our mind, understanding, reasoning, perceptions, beliefs and learning must reflect practical

purpose and any approach or methods must be founded on applicability and effectiveness

of ideas and concepts, thus knowledge (Hookway, 2017).

Constructivism. According to Constructivism, human knowledge is the product of

continual buildup of ideas and concepts tested with time by humans. Base on the progress

of human societies, humans acquire, compare and scrutinize the accumulation of facts and

theories which then either assimilated to our preexisting body of knowledge, otherwise

discarded. Also, the constructivist view knowledge as parts that is assembled through

gradual, step-by-step process (Kuhn, 1970).

Epistemological Anarchism. This theory states that there is no universal approach or

method central to the growth of knowledge that has cannot be limited by the consequences

of logical and epistemological assumption that any methods assumed of. It holds that the

idea of the operation of science by fixed, universal rules is unrealistic, pernicious, and

detrimental to science itself. The use of the term anarchism in the name reflected the

methodological pluralism prescription of the theory, as the purported scientific method

does not have a monopoly on truth or useful results (Lakatos et al., 1990).

Polytechnic University of the Philippines Page 27 of 84

Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment (STSE) Alejandro Jose Carreon Reboa

Rationalism

French mathematician, scientist and philosopher Rene

Descartes (1596–1650) is best known for his philosophical

work “Meditations on First Philosophy” and the

“Cartesian” Coordinate system named in his honor,

connecting geometry and algebra. Together with Spinoza

and Leibniz, he is the main proponent of the Rationalism,

known for his famous saying “I think, therefore I am”.

Realism

Painting of the two great Greek philosophers, Plato (left)

and Aristotle (right) discoursing. A former student of

Socrates, Plato (approx. 428 – 347 BCE) together with his

student Aristotle (384–322 BCE) have greatly influenced

Western Philosophy. They are also the main proponent of

the philosophy Realism.

Idealism

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) is a German philosopher

known for his magnum opus “Critique of Pure Reason”