Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Capital Values P10488

Uploaded by

ElaineOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Capital Values P10488

Uploaded by

ElaineCopyright:

Available Formats

Capital values

© University College of Estate Management 2016 P10488

Contents

1 Introduction....................................................................................................

1.1 Purposes of valuation......................................................................................

1.2 Method of valuation..........................................................................................

2 The investment method and constant incomes.........................................

3 Variable incomes...........................................................................................

3.1 Types of variable income.................................................................................

3.2 Alternative methods of valuation......................................................................

3.3 All risk yield method.........................................................................................

3.4 Equated yield method (DCF)...........................................................................

4 Stepped incomes.........................................................................................

4.1 Deferred income............................................................................................

4.2 Varying incomes in freehold property............................................................

4.3 The hardcore or layer method of valuation....................................................

4.4 Rents fixed in the medium term.....................................................................

4.5 Rents fixed in the long term...........................................................................

4.6 Equivalent yields............................................................................................

4.7 Equated yields...............................................................................................

4.8 Commentary on stepped income values.......................................................

5 Incomes for limited periods........................................................................

6 Terms and conditions of use......................................................................

1 Introduction

1.1 Purposes of valuation

The capital value of real estate is required for sale, purchase, investment or

mortgage purposes, taxation and condemnation (resumption or compulsory

purchase).

1.2 Method of valuation

The method employed is sales comparison or investment in most cases. Here

we shall be considering the investment method, both in conventional form and

discounted cash flow.

The investment method applies in the following contexts:

1. Constant incomes

2. Variable incomes

3. Stepped incomes (rising or falling, but some care is needed for the latter)

4. Incomes for limited periods.

2 The investment method and constant

incomes

The investment method applied to constant incomes illustrates the simplest

case. Where real estate produces a constant rent and that rent is well secured,

the investment has many similarities to a bond. The ratio of income to capital

value will tend to be similar.

For example, if a Government bond, undated, has a market yield of 5% pa. The

value of a secure, fixed rent in perpetuity is likely to reflect a yield of 6% pa.

Rent in perpetuity $5 000 pa

× 100 ÷ 6 (or YP) 16.667

Estimated capital value $83 335

The margin of the property income yield over the bond yield may vary, and

comparisons with actual property transactions should be studied to guide you

as to the relationship.

The reason for the mark-up on bonds yield is better liquidity and less

management in the case of bonds.

Constant incomes from property are not as common as variable incomes.

© UCEM 2016 Page 1 of 33

3 Variable incomes

3.1 Types of variable income

The majority of incomes from real estate are variable as opposed to constant.

There are two main kinds of variable income:

1. Where the rents are set at the market level, but are subject to future

changes.

2. Where the rents are above or below the market level and will be

adjusted in future to the market level. This is referred to as ‘stepped’

income, or, in UK practice, a reversionary income.

Here we are looking at those situations where the rents are at market level but

will change in future.

3.2 Alternative methods of valuation

There are two alternative methods of approach, one relying on simple

comparisons of ratios of rent to capital value, and the other on principles of

discounted cash flow. They are referred to as ‘All Risk Yield’ (ARY) and

‘equated yield’ (or DCF) methods respectively.

3.3 All risk yield method

The simple model, applied to a fee simple interest (i.e. a perpetuity for practical

purposes), is as follows:

Current rent income $10,000

Less landlord’s expenses 1,000

Net income (before tax) 9,000

× YP perpetuity @ 7.5% (100

8 )

12.5

$112,500

3.3.1 Explanation

1. Current rent. This has been compared with rents in the locality and

judged to be equal to market rental value.

2. Landlord’s expenses. All costs of repairs, insurance, management etc

not recovered from the tenants. In modern leasing of major buildings,

such costs are usually recovered in a service charge, unless the whole

building is let and the tenant maintains and insures. Where the landlord

is responsible for repairs and other costs, an estimate must be made

from records and comparable premises to ascertain the annualised costs

(local property taxes are assumed to be paid by tenants).

3. Years’ Purchase (YP). Simply a name for the multiplier, and the

reciprocal of the rate percent required by investors. The number (yield or

capitalisation rate) is extrapolated from sales data of similar deals.

© UCEM 2016 Page 2 of 33

The rate percent employed is known as the all risk yield since it reflects

all the benefits and risks etc associated with the investment.

3.3.2 Critique

1. The model, being very simple, conveys little direct information to a buyer

or seller.

2. The selection of the capitalisation rate is critical, but subjective

adjustments have to be made in practice for various differences between

properties, e.g.:

Location

Building quality

Tenants and leases

Lease unexpired term.

3. The method is an extension of the comparative principle, using

comparison for rental value and yield. It follows the market prices, and

suffers from the weaknesses involved in that practice, e.g. backward-

looking at previous deals, not forward-looking at prospects for the estate

being valued; over-values in an overheated market.

4. The all risk yield approach was developed in times of relative stability of

prices, and is not well suited to valuation under varying inflationary

conditions.

3.4 Equated yield method (DCF)

In choosing between alternative investments, including property, an investor will

be interested in certain information. In particular he may wish to know some or

all of the following:

1. Initial yield — the relationship between initial income and capital value,

and which provides an indicator of the potential future rental growth.

2. Reversionary yield — the relationship between future income and

capital value, and which provides a measure of risk for future income.

3. Equivalent yield — the ‘weighted’ average rate of return on stepped

incomes without specific allowance for income growth (see later in this

paper).

4. Equated yield — the internal rate of return with specific allowance for

income growth.

Equated yield analysis evolved in response to the criticism of conventional

valuation methods, namely that they are based upon current estimates of

market rent and only implicitly allow for inflation by adjusting the ARY (all risks

yield). Equated yields are based upon explicit projections of estimated future

rents allowing for an assumed annual growth rate.

© UCEM 2016 Page 3 of 33

An equated yield may be defined as that discount rate which must be applied to

the projected rental income from an investment so that the summation of all

such income discounted at this equated yield rate equates with the initial capital

outlay. In other words the equated yield is the IRR (Internal Rate of Return) of

an investment, where the income is assumed to vary over time as a result of

inflation and/or real growth in values. Where income is constant over time then

IRR = ARY.

3.4.1 The calculation of the equated yield

There are four variables to be considered in equated yield analysis. These are:

1. The all risks yield

2. The annual rate of growth of rental income

3. The rent review period

4. The equated yield.

Used as an analytical technique, equated yield analysis is designed to

ascertain the equated yield itself. The equated yield of an investment is

determined as follows.

The capital value of the investment is calculated in the conventional

way by capitalising the rent receivable using the ARY.

The future pattern of rental income is then determined by projecting

the market rent (MR) at an appropriate growth rate, using the

relevant amount of $1 function.

A correspondingly increased rent is therefore assumed to be

receivable from the date of each rent review.

This growth projection continues for the holding period. The rent

then receivable is capitalised into perpetuity at the ARY to give an

‘exit’ price.

The income flows are then discounted at that rate of interest which

will equate the sum of their present values with the capital outlay.

This rate of interest will be the equated yield.

Example 1

It is desired to calculate the equated yield of an investment yielding$100

per annum which is the current MR.

It is assumed that:

The ARY is 7.5%

The annual rate of growth of rental income is 5%

The rent review period is five-yearly.

Conventional valuation

The first step is to calculate the capital value of investment using

conventional methods:

© UCEM 2016 Page 4 of 33

$

MR 100

×YP perp @ 7.5% 13.33

Capital value (initial outlay) 1,333

The second step is to calculate the equated yield (EY) by means of a

discounted cash flow analysis. The correct cash flow table is given below.

×Amt

×PV of

Initial of£1 n MR on ×YP 5yrs Present

Year £1 n yrs

MR* yrs @5% review @12.5% value

@ 12.5%

(growth)

1—5 £100 — — 3.561 £356.06

6—10 £100 1.276 £127.63 3.561 0.555 £252.18

11—15 £100 1.629 £162.89 3.561 0.308 £178.60

16—20 £100 2.079 £207.89 3.561 0.171 £126.49

21—25 £100 2.653 £265.33 3.561 0.095 £89.59

26—30 £100 3.386 £338.64 3.561 0.053 £63.45

31+ £100 4.322 £432.19 13.333ˆ 0.029 £168.28

£1,234.65

* gross of tax Less initial outlay £1,333.00

Net Present Value -£98.35

ˆ Exit yield of 7.5% in perpetuity

Try at 11.5%

×Amt of

×PV of£1

Initial £1 n yrs MR on ×YP 5yrs Present

Year n yrs@

MR* @ 5% review @11.5% value

11.5%

(growth)

1—5 £100 — — 3.6499 — £364.99

6—10 £100 1.2763 £127.63 3.6499 0.5803 £270.30

11—15 £100 1.6289 £162.89 3.6499 0.3367 £200.18

16—20 £100 2.0789 £207.89 3.6499 0.1954 £148.25

21—25 £100 2.6533 £265.33 3.6499 0.1134 £109.79

26—30 £100 3.3864 £338.64 3.6499 0.0658 £81.31

31+ £100 4.3219 £432.19 13.3333ˆ 0.0382 £219.97

£1,394.80

* gross of tax Less initial outlay £1,333.00

Net Present Value £61.80

© UCEM 2016 Page 5 of 33

ˆ Exit yield of 7.5% in perpetuity

61.80

IRR=11.5+ ×1=11.886%

160.15

Check calculation:

× Amt of

× YP 5 × PV of £1

Initial £1 n yrs MR on Present

Year yrs @ EY n yrs @ EY

MR* @ 5% review value

(11.886%) (11.886%)

(growth)

1—5 £100 — — 3.6150 — £361.50

6—10 £100 1.2763 £127.63 3.6150 0.5703 £263.13

11—

£100 1.6289 £162.89 3.6150 0.3253 £191.53

15

16—

£100 2.0789 £207.89 3.6150 0.1855 £139.42

20

21—

£100 2.6533 £265.33 3.6150 0.1058 £101.48

25

26—

£100 3.3864 £338.64 3.6150 0.0603 £73.87

30

31+ £100 4.3219 £432.19 13.33333ˆ 0.0344 £198.32

£1,329.25

* gross of tax Less initial outlay £1,333.00

-£3.75

(i.e.

Net Present Value

effectively

nil)

ˆ Exit yield of 7.5% in perpetuity

Notes

1. The equated yield is 11.886%, i.e. it is that rate of return which

discounts the cash inflows to a figure which, when summated, is

equal to the initial outlay. This may be found by trial and error or

using IRR function of spreadsheet etc.

In guessing the first trial rate, a rough approximation of the equated

yield may be found by adding the growth rate to the initial yield (e =

k + g) where k = ARY, g = % growth. This would be 7.5% + 5% or

12.5% (plus or minus 1%). This, of course, ignores the rent review

pattern but does give a starting point.

If this produces a negative for the NPV figure then the next guess

would be lower at say 11.5% to give a positive NPV, which can

then be used to interpolate, using:

© UCEM 2016 Page 6 of 33

IRR = lower trial rate +

[ NPV1

NPV1 + NPV2

× trial rates difference

]

Where

NPV1 = NPV at lower trial rate

NPV2 = NPV at higher trial rate

As such the equated yield is comparable to the redemption yield on

other kinds of investment, or the internal rate of return.

2. Each ‘tranche’ of five years for which the income is fixed may be

discounted as a whole rather than for individual years by

multiplying by the years’ purchase for five years (which is only

another name for the Present Value of $1 per annum).

3. The final estimate of MR, i.e. that payable after 30 years, is

multiplied by the years’ purchase in perpetuity at the ARY of 7.5%

to reflect (implicitly) any future growth beyond 30 years.

4. Whilst the above calculation was done on a gross-of-tax basis, the

method can easily be adapted so as to produce a net-of-tax result.

Thus both cash flow and equated yield would be reduced by the

investor’s marginal rate of tax. Incidental costs and management

expenses can also be taken into account.

Obviously, to construct a discounted cash flow table every time it is required to

find the equated yield of an investment would prove a long and arduous task.

The use of computers together with software means that the equated yield can

be readily calculated, and there are published tables (Parry’s IRR) that can also

be used.

3.4.2 Equated yield as an investment criterion

Equated yields are often used as a means of comparing property with other

forms of investment. If the equated yield of a property investment is higher than

the investor’s opportunity cost of capital, then, other things being equal, it will

be a worthwhile investment to pursue. The difficulty here lies in determining the

opportunity cost of capital. The general consensus appears to be that this

should be the yield on long or undated bonds plus a margin of 2% for risk.

A historical view of property investments, going back to the time when

inflation/growth was not a problem and bonds were regarded as the safest form

of investment, shows that investors required a higher rate of return on property

than on bonds.

It can be expected that investors still require a higher actual (net redemption or

equated) yield from property than from bonds, for the same reasons as they did

historically, i.e. property is more trouble and more costly to manage, buy and

sell, even though rents may be very secure on good class premises.

© UCEM 2016 Page 7 of 33

Given the facts in Example 1, however, the decision as to whether the investor

would be advised to pursue this particular investment depends upon the

amount (if any) by which the equated yield exceeds the opportunity cost of

capital rate (taken at 2% above the yield on long-dated bonds). If bonds are

assumed to be showing a yield of approximately 5%, the equated yield of

11.886% is comfortably in excess of the ‘target’ of 7% (5% plus a 2% margin to

cover risk). Consequently the investment appears to be worthwhile.

3.4.3 Note

It is a fact that in some years the initial yields from rack-rented prime

commercial property have commonly been below 6% compared with 11+%

which was obtainable from gilts. Why is this? Why should an investor accept

such a situation? The answer lies in the growth prospects of the property

investment. The difference between 11% on gilts and 6% property is the

measure of the market’s view of how rents will move in future. This statement is

a little simplistic since it ignores the existence of rent reviews, but the ‘reverse

yield gap’ (11% − 6% = 5%) is compensated by future growth, and in accepting

6% on property the market is making a judgment about what that growth will be.

3.4.4 Calculating the rate of growth implicit in an investment

Using DCF

Equated yields can also be used analytically to calculate the rate of growth,

which (see note above) has been assumed implicitly by an investor acquiring

an investment at a known ARY. The procedure is to undertake a discounted

cash flow analysis using the opportunity cost of capital as the ‘target’ equated

yield. It is then possible to calculate the rate of rental growth required to

produce a future income flow that will equate with the initial capital outlay when

discounted at the target rate and summated. Once the rate of growth has been

calculated it should then be possible to consider the probability of achieving the

rate, given suitable evidence of trends. (See Example 2.)

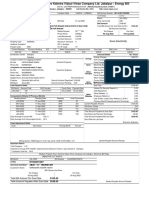

Example 2

A shop has recently been let at its MR of $10 000 per annum for 20

years (FRI) subject to five-yearly rent reviews. The property is on the

market for $145 000, which represents an ARY of 6.9%. Assuming that a

potential investor requires a gross ‘target’ equated yield of 12% (i.e. this

is his opportunity cost of capital rate), what is the minimum rate of rental

growth which must be achieved in order for the investor to be justified in

offering the asking price?

It is assumed that the investor will hold the property for 30 years and that

it will be readily re-let/renewed at the end of the existing lease.

Once again, trial rates should be taken and interpolated.

The final cash flow calculation is shown below:

© UCEM 2016 Page 8 of 33

Projected

income

(gross of

Presen

Cash tax) YP×PV of $1

Year t value Remarks

out $ assumin @ 12%

($)

g 7% pa

growth

($)

145,00 Purchase

0 — 1

0 price

-

8,700 153,70 + costs @ 6%

0

1−5 10,000 (YP 5 yrs) 3.6 36,000

Rent

increased by

6−10 14,026 3.6×0.567 28,630

amt of $1 in5

yrs

11−1

19,672 3.6×0.322 22,804

5

16−2

27,590 3.6×0.183 18,176

0

21−2

38,697 3.6×0.104 14,488

5

26−3

54,274 3.6×0.058 11,332

0

Sale price at

ARY adjusted

(YP perp

for

@7.5%×PV3

31 + 76,123 33,875 obsolescence

0 yrs @12%)

, deferred at

0.445

equated yield

rate

Net present

11,605

value

Therefore the required rate of growth will be approximately 7% per

annum and between 5—6% if costs at 6% are ignored.

Notes

1. The yield on sale has been adjusted by 0.6% for this example, but there

could be a greater adjustment depending on the degree of

obsolescence.

© UCEM 2016 Page 9 of 33

2. It is assumed that the lease will be renewed or the property re-let at the

end of Year 20.

3. For the purposes of the example, the investor is assumed to take a 30-

year view.

Using a formula

In terms of a formula, the simple:

k≈e−g

needs to be modified to take account of the growth in rents over the review

period. This may be proved as:

k = e − (ASF × P)

where

k = capitalisation rate

expressed as a decimal;

e = equated yield expressed

as a decimal;

ASF = annual sinking fund to

replace $1 at the equated

yield over the review

period (t);

and P = rental growth over the

review period.

Using the information in Example 2: Given

k = 0.069 (i.e. ARY = 6.9%) e

= 0.12

t = 5 yrs,

0.069 = 0.12 − (ASF @ 12% over

5 yrs × P)

0.069 = 0.12 − (0.1574P)

0.1574P = 0.12 − 0.069

P = 0.324 (i.e. 32.4% over 5

years).

To find out the rate of growth per year, the compound interest formula is used,

i.e.:

P = (1 + g) t − 1

where

g = growth per annum (as decimal)

t = review period.

So

© UCEM 2016 Page 10 of 33

5

1.324= (1+g)

1+g= √1.324 (or 1.324 ^2

5

1 + g = 1.0577

g = 0.0577 (or 5.77% pa)

Thus this is the average rental growth rate in perpetuity (ignoring incidental

purchase costs).

The formula above is also shown in some texts as:

YP perp at k% - YP t years at e%

(1 + g) t =

YP perp at k% × PV t years at e%

3.4.5 Equated yields used as a method of valuation

Equated yields can also be used to calculate the value of an investment to a

particular purchaser. The technique follows five steps.

1. Ascertain the investor’s opportunity cost of capital rate or ‘target’

equated yield.

2. Calculate the future cash flows by increasing rental income at an

anticipated growth rate.

3. Discount these future cash flows at the ‘target’ equated yield.

4. Calculate the Net Present Value of the sum of the discounted cash

flows. This figure will be the price which the investor can afford to pay for

the investment.

5. Compare the price found under (4) above with that calculated in

accordance with conventional valuation methods using the ARY.

Example 3

A secondary shop investment has been offered to your clients, a charity.

The premises are let to a well-established local trader on a lease which

has 15 years to run. The rent for that period is fixed at $5 000 per annum

without review. The current market rent of the property is $12 000 per

annum. Similar rack-rented property would sell to show an ARY of 8%.

How much should your client offer for the freehold interest?

1. The first step is to ascertain your client’s opportunity cost of

capital rate or target equated yield. Assuming that long-dated gilts

show a yield of 9%, such a target would probably be 9% plus a

margin of 2—3% to reflect the additional risks of property

compared with gilts, i.e. 12%. In this case, since your client is a

charity, there is no need to consider the target return net of tax.

2. Future income must then be increased by using an assumed rate

of rental growth. In this example it is assumed that there will be

© UCEM 2016 Page 11 of 33

growth in the market rent of 5% per annum. The market rent at

the end of the lease in 15 years’ time will therefore be $12 000

multiplied by the amount of $1 in 15 years @ 5% (or $12 000 ×

2.08 = $24 960 per annum). Future rental growth beyond 15

years (on the assumption of five-yearly rent reviews thereafter)

can be allowed for in a similar way, although in this example the

rent in 15 years’ time is capitalised at the ARY of 8% to reflect

rental growth beyond that date.

3. Discounting the cash flows at the target equated yield of 12%

produces the following ‘short-cut’ DCF calculation:

$ $

Term income 5,000

× YP 15 yrs @ 12% 6.81 34,050

Reversionary income 24,960

× YP perp @ 8% 12.5

× PV of $1 in 15 yrs @ 0.182 2.275 56,784

12%

90,834

4. Net Present Value (i.e. value to the investor) = $90 834.

5. A conventional valuation of the same property would produce the

following result:

$ $

Term income 5,000

× YP 15 yrs @ 10% 7.61 38,050

Reversionary income 12,000

× YP perp def 15 yrs @ 8% 3.94 47,280

Market Value (MV) $85,330

A yield of 10% is taken to value the term income in order to reflect the

fact that the rent is fixed, and therefore inflation-prone, for a long period.

From this example it will be noted that the investor would be prepared to

pay the Market Value of $85 330 given an opportunity cost of capital rate

of 12% and an assumed annual rate of rental growth of 5%.

Allowance for outgoings can be built into the DCF valuation by deducting

the anticipated outgoings (i.e. adjusted so as to reflect inflation) as a

negative cash flow.

3.4.6 ‘Real value’ approach

A second DCF-related approach is the so-called ‘real value’ approach of Wood

(1973), and developed by Baum & Crosby (1988). In broad outline the method

uses an Inflation Risk Free Yield (IRFY) which measures return by stripping out

and isolating the inflationary risk. It is thus a real rate of return.

© UCEM 2016 Page 12 of 33

The main difference between this and the equated yield approach is that the

equated yield model defines the growth in money terms as ‘g’ whilst real value

theory discounts income using a yield made up of IRFY and inflation.

In Example 3 a real value approach would produce the following valuation:

Term $5,000

× YP 15 yrs @ 12% 6.81 $34,050

Reversion $12,000

YP perp @ 8% 12.5

150,000

× PV $1 in 15 yrs @ 0.378 (1) 56,705

6.67%

Value 90,755 (compare with point 4

in Example 3)

3.4.7 Note

Notice how the term valuation produces the same figure as in point 3 of

Example 3. The approach on reversion is somewhat different, however: rent is

not inflated, and the IRFY is used to discount the income at a rate of 6.67%.

This is derived from:

1+e

i= -1

1+g

i.e.

1.12

i= -1

1.05

= 0.0667 or 6.67%

3.4.8 Criticism of equated yields

The growth rate

It is a fundamental criticism of equated yield analysis that the assessment of

the rate of growth is a matter of conjecture, particularly in view of the

requirement to assess both the likely course of inflation and potential changes

in real value. Critics often quote the example of the problems which would have

been created in 1972 had the level of growth in City of London office rents been

projected into the future, given the imminent collapse of the ‘property boom’.

Nevertheless there is a long-term tendency for rental values to rise, and

equated yield analysis seeks to provide an estimate of such long-term growth

using the evidence of past trends, combining this with the skill and informed

judgment of the valuer. Despite this, long-term predictions are most appropriate

for pension funds and institutions rather than for short-term investors looking,

say, to a 10— to 15—year ‘time horizon’.

© UCEM 2016 Page 13 of 33

Many of the major surveying firms publish the results of research undertaken

specifically for the purpose of providing advice for investors on the likely future

pattern of rental and capital growth. It is undoubtedly true that today there is a

relatively sounder empirical base for predicting growth.

It is important to distinguish the valuer’s role as an adviser on market value and

an adviser on investment. In both, rental growth predictions will be important

but in the latter role he may be in a position to judge, for instance, that a

particular purchase is unwise because it is based on future income predictions

with which he does not agree.

The opportunity cost of capital

Equated yield analysis is also criticised for its use of the yield on gilt-edged

stock as the basis of the ‘target rate’ against which to measure the equated

yield from a property investment. Many investors, particularly the large

institutions, will seek a diversity of investments within their portfolio and it does

not necessarily follow that the overall yield required will exceed that on

Government stock. Diversification often entails a sacrifice of yield in the short

term, and if the rate on gilts is adopted, then investment decisions would tend

to be made with a view to short-term expediency rather than long-term

planning.

Nor should a single yield criterion necessarily be applied to the whole range of

property investments, particularly one which is largely determined by external

factors such as the minimum lending rate. The correlation between changes in

the Base Rate and changes in the initial yields of property is not readily

apparent. There is a considerable time lag before economic trends will affect

property yields, and consequently changes in the Base Rate, which are quickly

reflected in changes in the yield on gilts, will produce sudden changes in the

implied rate of rental growth which may not be warranted in practice in the

market.

(Note: The adoption of the yield on gilts as the basis of the ‘target’ equated

yield does not necessarily mean the adoption of that rate on any particular day.

A long-term view of the likely average level of the rates on gilts should be

taken.)

Exit price

The method for calculating the equated yield, which was described above,

capitalised the rental value after 30 years at ARY, thereby allowing for

continuing rental growth. It could be argued that the likelihood of physical and

economic obsolescence after this time would be more accurately reflected by

using the equated yield (the ‘non-growth’ rate) to capitalise such rent. The

result of this would be to lower the equated yield.

Thus for an investment with an initial yield of 10%, five-yearly rent reviews and

growth at 10% per annum, the corresponding equated yield would be 18.46% if

© UCEM 2016 Page 14 of 33

the rent is capitalised after 30 years at the initial yield. It would be 17.96% if the

non-growth capitalisation factor were used.

3.4.9 What happens in practice?

As always, with the techniques on offer in a vocational subject such as property

valuation, it is worth asking which techniques practitioners use. The report

produced by Crosby (1991) provides valuable information on freehold

reversionary investment techniques. Certainly most academic commentators

and practitioners would argue that explicit DCF-based approaches are

appropriate for appraisal or analysis of worth (or valuation to an individual

purchaser). It is a matter of considerable debate whether such techniques

should be used for market valuation as well, however.

DCF-based models for property appraisal fall into two main groups, as we have

seen:

growth-explicit DCF such as equated yield analysis

real value approaches.

The former is more common in practice, as the survey found. An appraisal of

worth was found to be carried out by substantial numbers of valuers for

purchasers and sellers (Table 1).

Table 1: Appraisal of worth

Purchasers % Sellers %

Yes 76.2 61.9

No 13.8 29.4

No response 10.0 8.7

As regards the type of growth-explicit DCF analysis caused, Table 2 shows the

details.

Table 2: Investment analysis techniques (%)

DCF (gross of

DCF (net of tax) Other

tax)

Yes 30.08 20.33 15.45

No 31.71 39.02 20.33

No response 38.21 40.65 64.22

© UCEM 2016 Page 15 of 33

The most popular approach (30%) is DCF gross of tax. The survey did,

however, find some confusion over the distinction between market valuation

and appraisal of worth.

Most recent surveys suggest that many valuers use several methods and

compare results before aiming at a final valuation figure. Whichever method is

used, they always need to ‘look over their shoulder’ at what is happening in the

market itself.

4 Stepped incomes

4.1 Deferred income

A deferred income is an income which will not be received until after a given

number of years. Where no income at all is receivable while the investor is

waiting for the deferred income, the expected income is referred to simply as a

deferred income, or an income in a deferred investment. (See Example 4.)

Example 4

A property has a current market rent of $1 000 per annum. Your client is

entitled to receive this income, but not until 10 years have expired. Value

your client’s interest assuming a rate of 5%.

a) Value of deferred interest $

Current MR 1000

YP perp @ 5% 20

Capital value if receivable now 20 000

PV of $1 in 10 yrs @ 5% .614

Capital value of deferred income 12 280

It should be noted that the method of valuing a deferred interest is to

value it as if it were not deferred, and then to multiply this sum by the

present value for the period of deferment. This is consistent with the

basic principle of investment valuation, which is to discount future

income.

A neater way to set out the valuation of such a deferred interest is to

multiply the YP by the PV of $1 figure first, and then to use the modified

YP, as shown below.

b) Value of deferred interest $

1000

Net income (as before)

pa

YP perp @ 5% 20.00

PV of $1 in 10 yrs @ 5% .614

© UCEM 2016 Page 16 of 33

YP perp deferred 10 yrs @ 5% 12.28

Present Value of deferred income 12 280

Where the future income is receivable in perpetuity, as in this example,

the same result can be obtained by using the table as shown in (c)

below. However, this table is not applicable to leasehold interests and it

is well for you to become thoroughly familiar with method (b) which

applies to all deferred incomes.

c) Value of deferred interest $

Net income receivable in perpetuity, but 1000

starting 10 yrs hence pa

PV of a reversion to a perpetuity of $1

12.28

per annum* @ 5% after 10 yrs

Present Value of deferred income 12 280

* Note that PV of reversion to a perpetuity of $1 pa is another name for

YP of a reversion in perpetuity.

A special type of deferred income arises when a property gives a current

income, together with the right to a higher or lower income in the future. In this

case the higher or lower income in the future may be regarded as a deferred

income, known as a reversion. The income receivable until the reversion is due

is referred to as the income during the term. Typical cases of this sort arise

when a landlord is receiving a rent less than the market rent of a property

because he may have granted a lease at a fixed rent for a given term some

time ago, and rental values have risen since the grant of the lease; or where

the building is old and the reversion is to a lower income in the site only.

When a lease ends the landlord can expect to receive the market rent on

reversion, but until then the landlord’s interest is said to comprise a term and

reversion. A purchaser of this investment would be purchasing a varying

income.

When valuing a deferred income which is receivable in perpetuity, no question

can arise as to whether a figure of years’ purchase should be based upon the

single or the dual rate percent principle. One rate percent only has to be

considered because in the case of a perpetual income, no sinking fund has to

be invested.

© UCEM 2016 Page 17 of 33

4.2 Varying incomes in freehold property

If the income from a property is likely to increase or decrease at some future

date, the valuer will need to use the technique of valuing a deferred income to

account for this anticipated change.

As mentioned above, such a situation will usually arise in circumstances where

a property is let for an unexpired term and the rent reserved currently is below

or above the market rent.

Example 5 (See Figure 1)

A shop is let on a lease on full repairing and insuring terms with three

years of the lease unexpired, the rent reserved being $20,000 pa. The

current market rent is at present $50 000 pa on full repairing and

insuring terms. What is the value of the freeholder’s interest?

From first principles

The value of the shop is equal to the present value of the future income,

discounted at the appropriate rate percent derived from analysis of

comparable transactions. Assuming the appropriate yield to be 8%, the

value of the term would be as follows.

Term

PV of $@ Net present

Income $ Year $

8% value

20,000 1 .926 18,520

20,000 2 .857 17,140

20,000 3 .794 15 880

(Term) 51

(2.577)

540

To this must be added the value of the reversion:

Net present value

$

$

Value of reversion:

Market rent 50,000

YP (PV of $1 pa) in perp @ 8% 12.5

625,000

Discounted: PV of $1 in 3 yrs @

.794 (Reversion) 496,250

8%

Capital value 547,790

The problem is more conveniently dealt with as follows:

© UCEM 2016 Page 18 of 33

Freehold shop $ $

Term income 20,000 51,540

(compare

above)

YP (PV of $1 pa) in perp @ 8% 2.577

Reversionary income 50,000

YP perp deferred 3 yrs @ 8% 9.925 496,250

547,790

It may be suggested that the income could be higher (or lower) than $50 000 in

another three years. This factor is, however, reflected in the discount rate of 8%

which is determined by the market as the appropriate rate to reflect prospects

of growth or decline.

Note the use of the single rate YP table, which gives the same result as the

present value of each year’s rent considered separately.

Two further points should be considered.

1. The figure for ‘years’ purchase of a reversion to a perpetuity’ can be

derived from the valuation tables directly, but it is simply the product of

YP in perpetuity and present value of $1 after t years, where t is the term

or deferment period.

2. The income during the term may be more secure than a full rent if the full

rent exceeds the rent currently payable. The tenant is very unlikely to

default, e.g. when in financial difficulty or if rental values fall, and it is

usually therefore valued at a lower rate. A 1% reduction from the 8%

‘going rate’ is appropriate here. At very low yields an adjustment of 0.5%

and at high yields 2% are suggested, but it is not possible to be precise.

The valuation of the term and reversion in Example 5 is as follows:

Example 6 Shop: freehold interest subject to occupation lease

Term $ $

Rent passing 20,000

Outgoings: nil

YP 3 yrs @ 7% 2.62 52,400

Reversion

Market rent (at today’s prices) net 50,000

YP reversion to a perp after 3 yrs @ 8% 9.923 496,150

548,550

© UCEM 2016 Page 19 of 33

Estimated value as at date of valuation (say) 550,000

The rents and the yields reflect the various factors to be considered in the

valuation. These include physical factors, such as location, condition and

quality of buildings, size and environment; and economic and statutory aspects,

such as the local economy and planning policies. The type of tenant, whether a

national company, local company or private individual, is reflected in the yield.

Any valuation is subject to structural survey and legal investigations as to the

title and the rights of leaseholders and other interested persons, if any.

Figure 1: Rising income: freehold shop (Example 5)

4.3 The hardcore or layer method of valuation

The ‘traditional’ or term and reversion approach to valuation is based, as we

have seen, on the premise that income received during the term is valued at a

lower yield to reflect the additional security over reversionary income which is

valued on the ‘reversionary’ or ‘market’ yield basis.

During the 1970s, however, valuers in the UK began to use an alternative

approach to valuing incomes in freehold property. The ‘hardcore’ or ‘layer’

method, as it is known, values the current rent receivable into perpetuity and

then capitalises the marginal rent receivable on reversion at a higher rate of

interest to reflect the risky, top-slice nature of the marginal (or incremental)

income. Effectively, the difference is that the term and reversion approach

divides the income vertically whilst the hardcore divides it horizontally.

The main reason why the hardcore method, using different rates, gained

popularity during this period was that the UK government introduced a rent

freeze between 1972 and 1975. This, together with the general property slump

in the mid-1970s, meant that reversionary income was considered to be a

higher risk than term income which could be valued in ‘perpetuity’ as the

hardcore ‘slice’. The rent freeze meant that market rent might not actually be

achieved on review, and this was the ‘marginal income’ traditionally valued at a

higher rate reflecting risk.

© UCEM 2016 Page 20 of 33

Example 7 shows the two methods, with capitalisation rates designed to

produce similar answers.

Example 7

Refer to Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Suppose a property was producing an income of £6 000 pa (on FRI

terms) and that a review to MR of £10 000 pa was expected in three

years’ time. Given that the appropriate reversionary yield was 5%, the

two methods of valuation would take the following form:

1) Term and reversion

$ $

Rent received 6,000

YP 3 yrs @ 4.5% 2.75 16,500

Reversion to MR 10,000

YP perp @ 5% def. 3 yrs 17.28 172,800

Capital value 189,300

2) Hardcore

$ $

Rent received 6,000

YP perp @ 4.5% 22.22 133,300

Marginal top slice income 4,000

YP perp @ 6.0% def. 3 yrs 14 56,000

Capital value 189,300

Figure 2: Term and reversion

© UCEM 2016 Page 21 of 33

Figure 3: Hardcore

1. In order to arrive at the same value as the term and reversion method, a

yield of 6% on the marginal income (compared with the true reversionary

yield of 5%) has to be used in the hardcore method. The derivation of

this yield is found by an incremental approach and is essentially an

arithmetical manipulation, which may not be a logical reflection of the

market. Critics also argue that the method involves an artificial division of

income in reversion, since the whole income is at risk and not just the

marginal income.

2. In the hardcore method, if rates of 4.5% for hardcore income and 5% for

the increment were used, a different answer from the term and reversion

method would be obtained because of the mathematics of the respective

calculations. This raises the related issue to (1) above of what rates to

use or whether arithmetical manipulation is carried out to give the same

result as the term and reversion method. It is for these reasons that an

equivalent yield approach is often used in practice because it is a single

yield approach which will give the same answer whether it is applied in

the term and reversion approach or the hardcore approach.

However, this poses the question of which valuation method to adopt in

particular circumstances in the market, especially as valuers faced a volatile

market in the late 1980s. Two types of situation could arise, for example, when

different approaches could be adopted.

Scenario A. A relatively long term, say nine years, to a review; a

sizeable uplift to MR; and an ‘average’ tenant in occupation.

Scenario B. A short term, with a review to MR and a top class

tenant in occupation.

In Scenario A, a conventional term and reversion method will reflect the fixed

nature of the term income compared to a relatively risky increase to MR in nine

years’ time.

In Scenario B, the general market practice is to use an ‘equivalent yield’ or

same yield approach for the term and reversion because the quality of the

© UCEM 2016 Page 22 of 33

tenant means term and reversion are equally well secured. However,

circumstances may vary this; e.g., a large rental uplift, or a longer term to

review, increase risk in reversion and may lead to an upward adjustment of

reversionary yield. The equivalent yield approach is explained in more detail

later in this paper, as is the use of such approaches in practice.

The hardcore method with rate variations is therefore difficult to justify, although

the method is still appropriate under certain circumstances:

1. ‘Turnover’ rents where income falls naturally into ‘slices’ (i.e. a secure

‘base rent’ and an additional ‘marginal turnover rent’ which is based on

shop sales and is more risky).

2. Dealing with capital recoupment in variable profit rent (leasehold)

calculations (dealt with later).

3. Dealing with cases of ‘over-rented’ property. For example a 1960s office

block with five years to run, a MR of $80/m² but where the rent received

is $100/m²; or the case of temporary planning consent on a property

which provides a valuable user and a rent above the MR obtainable in

an alternative use when the permission expires. This would produce a

secure base rent and a higher risk top slice which would be lost when

the property became vacant or the planning permission expired.

4.4 Rents fixed in the medium term

Example 8 introduces the special problem which arises when the term income

is fixed for an unusually long period, in the example 20 years.

Comparable data used to derive yields will most commonly be from sales

where rents are reviewable at fairly regular intervals. The yields so derived are

applicable to capitalisation of rents fixed for the short term but are not directly

applicable to rents fixed for longer periods.

Rents which are fixed for terms of, say, 60 years or more, usually ground rents,

and which may often be treated as fixed in perpetuity (Example 9) can be

compared with fixed interest Government bonds (gilts) or (preferably) with other

ground rents, and the yields will be found to be relatively high (over 6% until

recently). The reason for the high yield is the inflation-prone nature of such

incomes. We should therefore expect yields to increase with the intervals

between rent reviews or, as in the following example, with the length of the

unexpired term.

Although the term rent is secure in actual terms, in real terms it is not so

secure, because the income itself diminishes in value in an inflationary period.

The yield has been adjusted upwards to reflect this.

Example 8

The property is a freehold warehouse of modern construction in a good

location. The warehouse is let on lease having 20 years unexpired at a

© UCEM 2016 Page 23 of 33

fixed rent of $5 000 pa. The tenants are responsible for all repairs and

insurance etc.

Similar warehouses let on leases with regular rent reviews have been

sold to show initial yields of 8%.

Term $ $

Rent passing 5,000

Outgoings: nil

YP 20 yrs @ 10% 8.51 42,550

Reversion

MR (from comparables) 7,500

YP perp deferred 20 yrs @ 8% 2.68 20,100

Capital value 62,650

4.5 Rents fixed in the long term

The most common example of long-term fixed rents are ground rents. UK

ground leases are usually granted for terms of 99 years or more, and until the

1960s the rent was usually fixed. Provisions for rent review are common in

leases granted since that date, but not universal, and the intervals between

reviews vary considerably. The freehold owner of property which is subject to

ground lease is entitled to the ground rent and the reversion to the building at

the end of the lease.

Whether the building has any economic value by the end of the term will

depend inter alia on the standard of construction and maintenance and the

character of the neighbourhood. There are, of course, many examples of

buildings which are life-expired in 100 years or less, and of buildings which are

still valuable though many years older. From a valuation point of view, distant

reversions are somewhat speculative, and by the time they have been deferred

for 60 years or more, make very little difference to a valuation. Therefore when

valuing ground rents fixed in the long term, it is usual to treat them as

perpetuities.

The valuations show that at these rates of interest, the significance of the

reversion is small. This tendency increases with the length of term and rate of

interest.

© UCEM 2016 Page 24 of 33

Example 9

Value the freehold interest in Alpha House, a block of offices erected

under the terms of a building agreement and lease. The lease has 60

years unexpired at a ground rent of $250pa. The offices are let at rents

totalling $20 000pa and the premises have been well maintained and

modernised.

Valuation of freehold interest

$ $

1 Ground rent 250

YP 60 yrs @ 12% 8.32 2,080

Reversion to site value 50,000

PV in 60 yrs @ 12% 0.0011 55

2,135

Alternatively

2 Ground rent 250

YP perp @ 12% 8.33

2,083

4.6 Equivalent yields

The equivalent yield represents the ‘overall’ rate of return on a reversionary

investment and is therefore the ‘weighted average’ yield, and will lie

somewhere between the capitalisation rates for term and reversion.

Example 10

It is desired to calculate the equivalent yield of a freehold investment

which is presently let at $10,000pa but which is due to revert to the MR

of $20,000pa in three years’ time. The full rental market yield is 8%, and

the term rent is to be valued at 6% for demonstration purposes.

$ $

Term rent receivable 10,000

YP 3 yrs @ 6% 2.673

26,730

Reversion to MR 20,000

YP perp def 3 yrs @ 8% 9.9229

198,458

Estimated capital value of freehold

225,188

interest

© UCEM 2016 Page 25 of 33

The investor now wishes to know the rate of return if the property is

purchased for a total cost of $225,188.

a. The initial yield

This represents the yield in Year 1 and is as follows:

10,000 (Rent)

×100 = 4.4%

225,188 (Capital)

This is not a lot of use, because it ignores the benefits of the

reversion. (But some investors have certain minimum initial yield

requirements.)

b. Yield on reversion

This relates reversionary rent to price:

20,000

× 100 = 8.88%

225,188

This is of interest to some investors, but is not very meaningful as

it ignores the effect of the term and in particular the length of time

until it is received.

c. Equivalent yield

This is the actual yield over time, reflecting the rent change and

term length.

Calculating the equivalent yield

The mathematics of the calculation are somewhat laborious since

there is no method which avoids trial and error.

A financial calculator with an ‘Internal Rate of Return’ programme

can do the necessary trials quickly, or a computer may be used.

a. Trial and error

By experience one can often make a reasonable guess for the

first trial yield. For example, it will lie between 6% and 8% (the

rates used in the valuation), and in this case nearer 8% than 6%

since most of the value lies in the reversion. Trying 7.5% we get:

Analysis to find equivalent yield

$ $

Term rent 10,000

YP 3 yrs @ 7.5% 2.6005 26,005

Reversionary rent 20,000

© UCEM 2016 Page 26 of 33

YP perp def 3 yrs @ 7.5% 10.7328 214,656

240,661

The result is too high; at a price of $225,188 the investor will

receive more than 7.5% (lower price = higher yield).

We therefore need to try again at 8% (which gives $210,351)and

interpolate between the ‘over’ and ‘under’ values to give

approximately 7¾%.

b. Solution of equivalent yield by formula

(AEG = Annual equivalent of gain)

Present income + AEG

Equivalent yield = ×100

Capital value

Gain on reversion × PV of $1 for the term

AEG =

YP for the term

Gain on reversion = Value on reversion less capital value

Value on reversion = MR$ 20,000

YP perp @ 8% 12.5

$250,000

∴Gain on reversion = $250,000 − $225,188 = $24812

$24,812 × PV of $1 in 3 yrs @ X%

∴ AEG =

YP 3 yrs @ X%

where X% is the equivalent yield and must be determined by trial and

error. An approximation of 7.5% is taken.

$24,812 × PV of $1 in 3 yrs @ 7.5% (0.805)

∴ AEG = = $7,682,002

YP 3 yrs @ 7.5% (2.6)

($10,000 + $7,682)

∴ Equivalent yield = ×100 = 7.85%

$225,188

The figure of 7.85% should be the same as that used to calculate the annual

equivalent of the gain. This latter figure was 7.5% and so the process should be

repeated until the two rates are equalised. The exact rate is 7.84% and often

the approximation used to calculate the annual equivalent of the gain will be

sufficiently close to ensure a reasonably accurate result. This formula solution

may be compared with the discounted cash flow method of solving the same

problem.

© UCEM 2016 Page 27 of 33

4.7 Equated yields

The methods considered above, i.e. term and reversion, hardcore and

equivalent yield, are built on the all risk yield approach, which uses today’s

rental values and makes no attempt to predict future rents.

The equated yield method, considered in the context of variable incomes, can

be used in the valuation of stepped incomes. It overcomes the problem of

subjectivity in yield adjustments in stepped incomes.

Example 11

Value retail premises let for four years at $40 000 per annum net.

Estimated rental value now $60,000.

k (initial yield at MR) = 6 % (5-yearly reviews)

e (equated yield) = 10 %

Find g:

K = e−(asf×P)

0.06 = 0.10−(asf at 10% for 5 yrs×P)

0.06−0.10 =−0.1638P

P = 24.42 % over 5 years

= 4.467 % pa

Given the implied growth from the analysis of sales on an equated yield

basis, either a ‘short-cut’ DCF, or full equated yield model, can be used.

Short-cut DCF

PV @

Value $

EY 10%

Current income $40,000 ×3.1699 126,796

Reversionary income $60,000

Increase over 4 years @ 0.04467 ×1.1910

71 460

YP Perp @ 6% 16.6667

1,191,001 ×0.6830 814,749

941,545

Compare ARY @ 6%

Current income$ 40,000

PV of $1 pa 4 years @ 6% 3.4651 138,604

Reversion $60,000

© UCEM 2016 Page 28 of 33

PV of $1 pa in perp deferred 4 years

13.2016 792,096

@ 6%

930 700

4.8 Commentary on stepped income values

1. A great deal of paper has been consumed in the debate on valuation

methods for reversionary incomes in the UK context. The models on

offer — term and reversion, hardcore and equivalent yield — have

theoretical advantages and disadvantages, but the differences they

produce in valuation terms are often overshadowed by other

considerations.

2. In a weak market, lease length and tenant quality are key

considerations, and property let on a short-term lease is relatively risky,

regardless of current rent level.

3. The use of equated yield rather than ARY models has been shown to

change valuation figures significantly, which suggests that all three ARY

methods are suspect. According to the Mallinson Report (1995), none of

the methods actually represents buyer behaviour. Nevertheless,

provided we ‘value as we devalue’, i.e. on the same basis and using the

same assumptions, the results are usually within an acceptable margin

of error.

4. The application of ‘product analysis’ to stepped rents or reversion shows

them to have some distinctive differences from rack-rented properties.

For example the financing of under-rented properties is a problem while

the income is low. For some buyers, this is important. Gains on resale

are higher for under-rented investments — an advantage for other

buyers.

5 Incomes for limited periods

Such incomes may be valued:

On a single rate, present value basis at an all risks yield appropriate

to the relative risk, security, growth aspects etc.

On an equated yield basis, which is appropriate for investment

worth.

On a dual rate basis.

The last method has been used in the UK for very many years and became the

rule for many statutory purposes.

Increasing criticism has caused it to decline in open market transactions, but

the concept still has some uses.

© UCEM 2016 Page 29 of 33

Reflection

2. A shop is let at $100 000pa for five years. It has a current rental

value of $140,000.

k (initial yield for rack-rented shops) is 5.5%; e (equated yield) is10%.

Value the fee simple interest by:

a. Term and reversion method

b. Hardcore method

c. DCF method, assuming a holding period of 20 years

d. Short-cut DCF method.

Note: The answer to this question is given overleaf.

3. Outline alternative methods to value an office building let at$140

000pa for the next 12 years, rent reviews after year 2 and year 7.

The current rental value is $100 000pa.

Assume k = 8%; e = 11%.

© UCEM 2016 Page 30 of 33

Answers to Self-Assessment Question 1

a. Term and reversion valuation

Current rent 100,000

YP 5 yrs @ 5.5% 4.27

427,000

Reversion to MR

MR 140,000

YP perp @ 5.75% 17.3913

PV of $ after 5 yrs @ 5.75% 0.756

1,840,695

$2,267,696

b. Hardcore method

Core income

Current rent 100,000

YP perp @ 5.5% 18.1818

21,818,182

Additional slice

MR 140,000

Core rent 100,000

Additional slice 40,000

YP perp @ 6.5% 15.38462

PV of $ after 5 yrs @ 6.5% 0.73

449,231

$2,267,413

c. DCF method over 20 years (assuming 5-yearly reviews)

Since k = 5.5%, e = 10%, therefore, (using k≈e - g) g = 4.5%approx

Calculate rental growth:

Amt of $ @ Rent with

MR Review

4.5% p.a. growth

$140,000 1.246 $174,440 After 5 yrs

1.55 $217,000 After 10 yrs

1.935 $270,900 After 15 yrs

2.412 $337,680 After 20 yrs

© UCEM 2016 Page 31 of 33

YP 5 yrs

Year Rent PV @ 10% NPV

@ 10%

0—5 $100,000 3.79 1 $379,000

6 — 10 $174,440 3.79 0.6209 $410,494

11 — 15 $217,000 3.79 0.3855 $317,047

16 — 20 $270,900 3.79 0.2394 $245,795

20+ $337,680 17.39* 0.1486 $872,683

TOTAL $2,225,018

* YP perpetuity @ 5.75%

d. Short-cut DCF method

As calculated above, g = 4.5% approx.

Term

Rent passing 100,000

YP 5 yrs @10% 3.79

$379,000

Reversion

Reversion to MR

($140,000)

X Amount of $ for 5 yrs 1.246 $174,440

@4.5%

YP perp @ 5.75% 17.391

$3,033,739

PV of $ 5 yrs @ 10% 0.6209

$1,883,649

$2,262,649

Comment

For this simple example, all four methods produce essentially the same

result after rounding to about $2 250 000 (remember, valuation is not an

exact science).

However, if the property had been over-rented, the first two methods

would, owing to their implicit growth assumptions in the yields adopted,

have produced too high a figure.

It should also be noted that the final yield in examples (c) and (d) has

been moved up by 0.25% to allow for obsolescence to the building.

© UCEM 2016 Page 32 of 33

6 Terms and conditions of use

Please note: this document is provided for information purposes only and does

not constitute legal, financial or other advice.

This digital copy has been made with the explicit permission of the copyright

holder (UCEM) and allows you to:

● access and download a copy;

● print out a copy.

This digital copy may only be used by you personally and strictly for your own

individual and personal use.

All rights reserved. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying,

storage or distribution (including by email) is permitted without written

permission from UCEM.

© UCEM 2016 Page 33 of 33

You might also like

- Learn To Value Real Estate Investment PropertyDocument13 pagesLearn To Value Real Estate Investment PropertyBIZUNEH NIGUSSIENo ratings yet

- Chapter 6-Income ApproachDocument37 pagesChapter 6-Income ApproachHosnii QamarNo ratings yet

- Typically Need To Employ Professional ManagementDocument15 pagesTypically Need To Employ Professional Managementd ddNo ratings yet

- Lex CaseDocument8 pagesLex CaseAshlesh MangrulkarNo ratings yet

- Venture capital funding stages and regulations in IndiaDocument35 pagesVenture capital funding stages and regulations in IndiadakshaangelNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 10 - CH18-1Document4 pagesTutorial 10 - CH18-1zachNo ratings yet

- CFA640 Portfolio Management Process and Models/TITLEDocument19 pagesCFA640 Portfolio Management Process and Models/TITLEaanand21100% (1)

- Fintech A Game Changer For Financial Inclusion April 2019 PDFDocument18 pagesFintech A Game Changer For Financial Inclusion April 2019 PDFSumeer BeriNo ratings yet

- Discounted Cash Flow Valuation The Inputs: K.ViswanathanDocument47 pagesDiscounted Cash Flow Valuation The Inputs: K.ViswanathanHardik VibhakarNo ratings yet

- Contemporary ValuationDocument21 pagesContemporary ValuationUnyime Ndeuke100% (1)

- Marriott Corporation The Cost of Capital Case Study AnalysisDocument21 pagesMarriott Corporation The Cost of Capital Case Study AnalysisvasanthaNo ratings yet

- WACC or Cost of CapitalDocument19 pagesWACC or Cost of CapitalSaeed Agha AhmadzaiNo ratings yet

- Soal Latihan 2Document4 pagesSoal Latihan 2Fradila Ayu NabilaNo ratings yet

- CAPMDocument43 pagesCAPMEsha TibrewalNo ratings yet

- Gross Fund Invests in Such Interest1Document5 pagesGross Fund Invests in Such Interest1Muha Mmed Jib RilNo ratings yet

- CAPM ReviewDocument24 pagesCAPM Reviewmohsen55No ratings yet

- Dividend Discount Model in Valuation of Common StockDocument15 pagesDividend Discount Model in Valuation of Common Stockcaptain_bkx0% (1)

- Chapter 5Document62 pagesChapter 522GayeonNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document8 pagesPresentation 1kitamuNo ratings yet

- Mar RiotDocument3 pagesMar RiotAnurag BohraNo ratings yet

- Solution To Previous Year Questions Course Code: Course Name: AdvancedDocument20 pagesSolution To Previous Year Questions Course Code: Course Name: AdvancedSHAFI Al MEHEDINo ratings yet

- R04 Capital Market Expectations, Part 2 - Forecasting Asset Class Returns HY NotesDocument7 pagesR04 Capital Market Expectations, Part 2 - Forecasting Asset Class Returns HY NotesArcadioNo ratings yet

- PFM15e IM CH06Document24 pagesPFM15e IM CH06Daniel HakimNo ratings yet

- sm11 Solution ManualDocument9 pagessm11 Solution ManualJood AdoodNo ratings yet

- Forecasting Asset Class ReturnDocument4 pagesForecasting Asset Class ReturnkypvikasNo ratings yet

- CAPM Assumptions and Extensions AnalysisDocument14 pagesCAPM Assumptions and Extensions AnalysisSrilekha BasavojuNo ratings yet

- R52 Fixed Income Markets Issuance Trading and FundingDocument43 pagesR52 Fixed Income Markets Issuance Trading and FundingDiegoNo ratings yet

- FinQuiz - Study Session 9, Reading 23Document8 pagesFinQuiz - Study Session 9, Reading 23Matej Vala100% (1)

- Interest rates explainedDocument8 pagesInterest rates explainedClaire Joy CadornaNo ratings yet

- Capitalization Rate Definition PDFDocument12 pagesCapitalization Rate Definition PDFGerald GallenitoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document10 pagesChapter 4Seid KassawNo ratings yet

- 4853 - CID-sessions 3-4-5Document35 pages4853 - CID-sessions 3-4-5Sidharth Ray100% (1)

- Module2 EconDocument45 pagesModule2 EconandreslloydralfNo ratings yet

- Securitization of IPDocument8 pagesSecuritization of IPKirthi Srinivas GNo ratings yet

- Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)Document25 pagesCapital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)ktkalai selviNo ratings yet

- Economics: Regulatory Arbitrage Regulation Used To Exploit Differences in EconomicDocument28 pagesEconomics: Regulatory Arbitrage Regulation Used To Exploit Differences in EconomicAniket JainNo ratings yet

- Ameri TradeDocument7 pagesAmeri TradexenabNo ratings yet

- SUBJECT CODE & NAME MCC 401 & Management of Financial ServicesDocument6 pagesSUBJECT CODE & NAME MCC 401 & Management of Financial ServicesMrinal KalitaNo ratings yet

- Group 3Document54 pagesGroup 3SXCEcon PostGrad 2021-23No ratings yet

- The Declining U.S. Equity PremiumDocument19 pagesThe Declining U.S. Equity PremiumpostscriptNo ratings yet

- 06 Cost of CapitalDocument13 pages06 Cost of Capitallawrence.dururuNo ratings yet

- 2023 L2 Glossary PDFDocument21 pages2023 L2 Glossary PDFsushantNo ratings yet

- Cost of Capital IntroductionDocument18 pagesCost of Capital IntroductionArif KhanNo ratings yet

- Arbitage Pricing TheoryDocument12 pagesArbitage Pricing TheoryKlarence Corpuz LeddaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9.3 (Final)Document5 pagesChapter 9.3 (Final)NGUYET LO MINHNo ratings yet

- TTS - Acquisition Comps PrimerDocument5 pagesTTS - Acquisition Comps PrimerKrystleNo ratings yet

- SAPM Unit-3Document18 pagesSAPM Unit-3Badrinath BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Derivatives NotesDocument4 pagesDerivatives NotesSoumyaNairNo ratings yet

- Unit 6Document4 pagesUnit 610.mohta.samriddhiNo ratings yet

- Long Term Sources of FundsDocument7 pagesLong Term Sources of FundsushaNo ratings yet

- Valuation of Securities Including Capital Asset ModelDocument11 pagesValuation of Securities Including Capital Asset Modelmayaverma123pNo ratings yet

- Sy CH - 5Document8 pagesSy CH - 5Rafayeat Hasan MehediNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Valuation: Chapter TWO: Return ConceptsDocument13 pagesFundamentals of Valuation: Chapter TWO: Return ConceptsAhmed RedaNo ratings yet

- Institute of Actuaries of India Subject CA1 - Paper I Core Applications ConceptsDocument23 pagesInstitute of Actuaries of India Subject CA1 - Paper I Core Applications ConceptsYogeshAgrawalNo ratings yet

- Differentiate Profit Maximization From Wealth MaximizationDocument8 pagesDifferentiate Profit Maximization From Wealth MaximizationRobi MatiNo ratings yet

- 18 Portfolio Management Capital Market Theory Basic ConceptsDocument17 pages18 Portfolio Management Capital Market Theory Basic ConceptsSin MelmondNo ratings yet

- Capm + AptDocument10 pagesCapm + AptharoonkhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 PFS3353Document6 pagesChapter 4 PFS3353dines1495No ratings yet

- 8524 UniqueDocument20 pages8524 UniqueMs AimaNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting MethodsDocument7 pagesCapital Budgeting MethodsCarl Angelo Lopez100% (1)

- Teknik AkersonDocument60 pagesTeknik Akerson060098401No ratings yet

- Elec5212 Module3 Cost of CapitalDocument37 pagesElec5212 Module3 Cost of CapitalshoaibshahjeNo ratings yet

- Summary of Philip J. Romero & Tucker Balch's What Hedge Funds Really DoFrom EverandSummary of Philip J. Romero & Tucker Balch's What Hedge Funds Really DoNo ratings yet

- Answer Silicon House LeaseholdDocument1 pageAnswer Silicon House LeaseholdElaineNo ratings yet

- The Real Estate Development Process P10218Document73 pagesThe Real Estate Development Process P10218ElaineNo ratings yet

- Residual Appraisals P10489Document24 pagesResidual Appraisals P10489ElaineNo ratings yet

- Profits Method of Valuation P10507Document9 pagesProfits Method of Valuation P10507Raymond LeeNo ratings yet

- Construction of Valuation Tables P10486Document17 pagesConstruction of Valuation Tables P10486ElaineNo ratings yet

- Construction of Valuation Tables P10486Document17 pagesConstruction of Valuation Tables P10486ElaineNo ratings yet

- Donoghue V Stevenson WorksheetDocument3 pagesDonoghue V Stevenson WorksheetElaineNo ratings yet

- Calculation - Estimation of ProfitDocument1 pageCalculation - Estimation of ProfitElaineNo ratings yet

- Northern Arc Capital Raises $25 Million Debt From FMODocument10 pagesNorthern Arc Capital Raises $25 Million Debt From FMOBSA3Tagum MariletNo ratings yet

- Monthly Value-Added Tax DeclarationDocument1 pageMonthly Value-Added Tax DeclarationGen ElloNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Financial Planning: Fundamentals of Corporate FinanceDocument17 pagesLong-Term Financial Planning: Fundamentals of Corporate FinanceMuh BilalNo ratings yet

- FABM2 - 12 - Q1 - Mod4 - Statement-of-Cash-Flow - V5 FSDocument20 pagesFABM2 - 12 - Q1 - Mod4 - Statement-of-Cash-Flow - V5 FSEllah OllicetnomNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Practice ExamDocument16 pagesChapter 2 Practice ExamShayma S.h.kNo ratings yet

- Embedded Derivatives in Host Contracts Under IAS 39Document170 pagesEmbedded Derivatives in Host Contracts Under IAS 39Anonymous JqimV1ENo ratings yet

- A Study On Deposit Mobilisation of Indian Overseas Bank With Reference To Velachery BranchDocument3 pagesA Study On Deposit Mobilisation of Indian Overseas Bank With Reference To Velachery Branchvinoth_172824100% (1)

- IFRS Financial Reporting and Asset ImpairmentDocument10 pagesIFRS Financial Reporting and Asset ImpairmentNitin ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Impact of COVID-19 on Philippine Peso and EconomyDocument4 pagesImpact of COVID-19 on Philippine Peso and EconomyRonaldo R. VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Aminul Islam 2016209690 EMB-660-Assignment-2Document35 pagesAminul Islam 2016209690 EMB-660-Assignment-2Aminul Islam 2016209690No ratings yet

- Inverstor'S Protection in Stock Markert: A Role of Sebi.Document7 pagesInverstor'S Protection in Stock Markert: A Role of Sebi.nikhilaNo ratings yet

- Activity 4Document1 pageActivity 4Coleen Joy Sebastian PagalingNo ratings yet

- Accounting Equation Removal.2Document3 pagesAccounting Equation Removal.2labsavilesNo ratings yet

- MBF14e Chap08 Interest Rate Derviatives PbmsDocument16 pagesMBF14e Chap08 Interest Rate Derviatives PbmsVũ Trần Nhật ViNo ratings yet

- Exercise 4. Perez Company Had The Following Transactions During JanuaryDocument3 pagesExercise 4. Perez Company Had The Following Transactions During JanuaryLysss EpssssNo ratings yet

- Intro Macroeconomics Course SyllabusDocument4 pagesIntro Macroeconomics Course SyllabusDominic DecocoNo ratings yet

- JS Bank of Pakistan Internship ReportDocument59 pagesJS Bank of Pakistan Internship Reportbbaahmad89100% (2)

- Ms May 20 p1rDocument17 pagesMs May 20 p1rTahmid MahabubNo ratings yet

- Loan Document For Test UserDocument11 pagesLoan Document For Test UserBenedict BabuNo ratings yet

- Understanding different conceptions of qualityDocument25 pagesUnderstanding different conceptions of qualityjaejudraNo ratings yet

- Genuine BSP Bank Notes and CoinsDocument5 pagesGenuine BSP Bank Notes and CoinsC H ♥ N T ZNo ratings yet

- ENG233 Ch2Document34 pagesENG233 Ch2Mikaela PadernaNo ratings yet

- Save Electricity: N1823001387 JBA1 - 6 - 1823001387Document1 pageSave Electricity: N1823001387 JBA1 - 6 - 1823001387Shikha KanojiyaNo ratings yet

- Investers Preference Towards Mutual FundsDocument24 pagesInvesters Preference Towards Mutual FundsritishsikkaNo ratings yet

- Galaxy Digital Research: Dogecoin: The Most Honest SH TcoinDocument22 pagesGalaxy Digital Research: Dogecoin: The Most Honest SH TcoinAhmad Mukhtar 164-FET/BSCE/F17No ratings yet

- Project Report On Mutual FundDocument95 pagesProject Report On Mutual FundRaghavendra yadav KM82% (11)

- Kotak Mahindra Group: Investor PresentationDocument34 pagesKotak Mahindra Group: Investor Presentationdivya mNo ratings yet