Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Early Mobility in The Intensive Care Unit Standard Equipment VS A Mobility Platform

Uploaded by

Bapak Sunaryo SPBUOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Early Mobility in The Intensive Care Unit Standard Equipment VS A Mobility Platform

Uploaded by

Bapak Sunaryo SPBUCopyright:

Available Formats

Early Mobility in Critical Care

E MOBILITY IN THE

ARLY

INTENSIVE CARE UNIT:

STANDARD EQUIPMENT VS

A MOBILITY PLATFORM

By Melanie Roberts, MS, APRN, CCRN, CCNS, Laura Adele Johnson, RN, BSN, CCRN,

and Trent L. Lalonde, PhD

Background Despite the general belief that mobility and exercise

play an important role in the recovery of functional status, mobil-

ity is difficult to implement in patients in intensive care units.

Objectives To compare a mobility platform with standard

equipment, assessing efficiency (decreased time and staff

required to prepare patient), effectiveness (increased activity

time), and safety (no falls, unplanned tube removals, or emer-

gency situations) for intensive care patients.

Methods This observational study was approved by the insti-

tutional review board, and informed consent was obtained

from the patient or the medical decision maker. Intensive care

patients were assigned to a room in the usual manner, with

platforms in odd-numbered rooms and standard equipment in

even-numbered rooms. Standardized data collection tools

were designed to collect data for 24 hours for each patient.

The nurses caring for the patients completed the data collec-

tion tools in real time during the activity. The stages of activity

and the physiological states that would preclude mobility were

very specifically defined for the research study.

Results Data were collected for a total of 71 patients and 238

activities. Important (although not significant) descriptive sta-

tistics regarding early mobility in the intensive care unit were

discovered. The unintended result of the research study was a

change in the culture and practice regarding early mobility in

the intensive care unit.

EBR

Evidence-Based Review on pp 458-459

Conclusions Early mobility can be implemented in intensive

care units. Standard equipment can be used to mobilize such

patients safely; however, for patients who ambulate, a plat-

form may increase efficiency and effectiveness. (American

©2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Journal of Critical Care. 2014;23:451-457)

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2014878

www.ajcconline.org AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2014, Volume 23, No. 6 451

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

D

espite the general belief that mobility and exercise play an important role in

the recovery of functional status, mobility is difficult to implement in patients

in intensive care units (ICUs). Several studies1-4 in the past 2 decades have

documented the outcomes of early mobility in critical care. Early and frequent

mobilization of ICU patients decreases hospital length of stay, ICU length

of stay, and ventilator days.1-4 Common critical care complications, neuromuscular weakness,

deconditioning, and delirium are decreased with early mobility.2,5-8 Morris et al9 demonstrated

that the lack of early mobility therapy in ICUs was 1 of the 4 variables associated with readmis-

sion or death during the first year for ICU survivors of acute respiratory failure.

Hospitals nationwide are attempting to develop Methods

mobility programs, but actualizing the goal is diffi- Setting

cult. Lack of resources, a lack of established proto- The study was completed at Medical Center of

cols, and staff resistance prevent many facilities the Rockies, a 136-bed nonprofit, tertiary care hos-

from implementing a successful mobility program.10 pital. Clinical areas involved in the research study

Numerous articles exist indicating the importance included a 12-bed cardiac/cardiovascular surgery ICU

of mobilization; however, little detail can be found (CICU) and a 12-bed surgical/trauma ICU (SICU).

to explain how to implement a successful mobility Mobility stages had been implemented in the ICUs

program. Published reports demon- before the study but were not integrated into practice.

Lack of early strate the importance of mobility A research protocol was designed to identify human

protocols in determining individual resources required for early mobility in the ICU, to

mobility is patients’ appropriateness for mobil- compare standard equipment with a platform, and

ity and to define progression of

associated with mobility, but few such protocols

to validate the safety of the protocol.

readmission to the have been published.11 Sample

The culture of the ICU must be The study included all intensive care patients

intensive care unit addressed early in any initiative to who were at least 18 years old and spoke English.

or death during implement a mobility program. Critical care patients are a vulnerable population of

Successful implementation of early patients; many are unable to make decisions because

the first year. mobility requires a change in ICU of cognitive impairment from medications and criti-

culture, nurses’ personal percep- cal illness. To protect the patients, informed consent

tions, and teamwork.10 This article describes how a was obtained from individual patients if their results

community-based hospital developed a mobility on the Confusion Assessment Method12 were nor-

program despite limited resources and changed the mal and the patient was not receiving any sedatives

culture of the ICU to accept the challenge of mobi- or pain medication. If the patient did not meet

lizing patients. both criteria, the patient’s medical decision maker

provided consent. Consent was obtained by spe-

cially trained ICU nurses at an appropriate time

after the patient had been admitted to the ICU,

About the Authors depending on the patient’s condition and planned

Melanie Roberts is a critical care Clinical Nurse Specialist mobility. For planned ICU admissions, consent was

at Medical Center of the Rockies in Loveland, Colorado. obtained before admission.

Laura Adele Johnson is a student registered nurse anes-

thetist at Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah. Data were collected for 4 months, with a total

Trent L. Lalonde is an associate professor of applied sta- of 71 patients enrolled in the study and 238 total

tistics at the University of Northern Colorado and a sta- mobility events. Of the 71 patients, 26 (37%) were

tistical consultant at the Medical Center of the Rockies.

female with a mean age of 66.00 (SD, 19.76) years,

Corresponding author: Melanie Roberts, MS, APRN, CCRN,

CCNS, Medical Center of the Rockies, 2500 Rocky Mountain

whereas the 45 males (63%) had a mean age of 68.62

Avenue, Loveland, CO 80538 (e-mail: Melanie.Roberts@ (SD, 12.43) years. A total of 49 patients (69%) were

uchealth.org). in the CICU and 22 (31%) were in the SICU. The

452 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2014, Volume 23, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

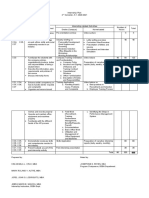

Table 1

Stages of mobility

CICU patients consisted of 15 females (31%) and 34 Stage Activity Research requirement

males (69%), with a mean age of 69.79 (SD, 12.37)

years. The platform was assigned to 23 (47%) of 1 Bed in chair position Not part of the research study

the CICU patients. The SICU patients consisted of 2 Dangle legs at edge of bed Minimum 2 min

11 females (50%) and 11 (50%) males, with a mean

3 Stand upright, weight bearing Minimum 1 min

age of 62.91 (SD, 20.24) years. The platform was

assigned to 12 (55%) of the SICU patients. 4 Chair, stand, pivot/march Minimum 15 min in chair

5 Ambulate Minimum 10 ft (3 m)

Design

A prospective, randomized, controlled, observa-

tional research study was designed to compare a to reeducate themselves on the equipment and the

platform with standard equipment for ICU patients. data collection tool as needed before data collection.

The research hypothesis stated expected improvements During the 2 weeks before the study, the nurses

in efficiency, effectiveness, and safety of ICU mobil- were given instructions by physical therapists on

ity when the platform was used rather than standard the proper method for assisting a patient out of bed

equipment. Effectiveness is defined as the duration to the chair and getting the patient back to bed

of activity performed by the patient. Efficiency is using a gait belt to promote staff and patient safety.

defined as the time to prepare the patient for The data collection sheets were gathered weekly

mobility as well as the number of staff required to and correlated with informed consent. If consent

assist the patient with the activity. Safety is defined had been obtained, the data sheets were entered

by the number of falls or unplanned tube removals. into a data spreadsheet. If consent had not been

The standard equipment used for the study obtained, the data collection sheet was shredded

includes a gait belt, no-slip socks, a walker, and a The ICU nurses determined that it was easier to

wheelchair if the patient was ambulating. The plat- collect the data sheets every day for all patients to

form is a mobile support device that consolidates avoid bias created by their knowledge of who was

equipment (intravenous poles, multiple hooks for enrolled in the study. The nurses were using a mobil-

drainage bags, and a secure location for oxygen) ity protocol with which they were familiar except

into a small area. The patient still requires a gait for the addition of the platform. The mobility pro-

belt and no-slip socks for safety. The design of the tocol used had 5 stages (Table 1), with specific

platform is to allow mobility with the assistance of definitions given for each stage. ICU nurses were

fewer staff. All patients were monitored, had oxy- responsible for determining whether it was safe for

gen, and if the patient was receiving mechanical the patient to mobilize. The expec-

ventilation, a respiratory therapist had to be part tation of the ICU nurse is to use

of the mobility team. the absolute exclusion criteria and Mobility was

The study was approved by the organization’s relative contraindications to deter- defined as

institutional review board. Platforms were placed in mine the patient’s ability to mobi-

odd-numbered rooms. Patients were admitted to lize. Patients start the protocol after purposeful

rooms by the usual process. Data were collected by 24 hours unless they meet 1 of the

the ICU nurses during the activity session, and time exclusion criteria.

movement with

was documented to the nearest minute. Standard- The absolute exclusion criteria the patient’s

ized data collection sheets were used to ensure that are based on the patient’s physiolog-

all appropriate information was recorded. The fol- ical condition: intracranial monitor, participation.

lowing information was collected for each activity: unstable pelvic or spinal fractures,

date, time of day, preparation time (minutes), physician’s order for deep sedation, therapeutic

activity time (minutes), type of activity (chair, dan- hypothermia, vasoactive medication titration, active

gle, stand or march in place, walk), number of staff bleeding, intra-aortic balloon pump or ventricular

required, frequency of activities per patient per day, assist device, comatose, open abdomen, and traction.

and unplanned tube removals or falls. Each patient Relative contraindications such as vasoactive infusions

had a data collection sheet for each day, starting at or changes in respiratory status or vital signs are deter-

midnight with the new ICU flow sheet. Before the mined by the nurse caring for the patient.

beginning of the study, the nurses had 2 weeks to Stage 1 activity, bed in chair position, would not

practice with the platform as well as the data collec- be included in the research study as mobility. Before

tion sheets to ensure that the data collection process the research study, the ICU had determined that

would work as expected. This process allowed nurses mobility would be defined as purposeful movement

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2014, Volume 23, No. 6 453

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

Table 2

Sample size of activities (n) for number of staff,

by activity type

To assess the impact of the platform on activity

No. of staff time, preparation time, number of staff, falls, and

Activity 0 1 2 3 4 5 Total unintended tube removals (endotracheal, gastric,

urinary, chest, and drains), means and standard

Platform deviations are reported for both treatments, by type

Chair 0 9 27 8 1 1 46

Dangle 0 2 14 11 4 0 31

of activity. To evaluate the significance of the dif-

Stand/march 1 2 8 9 3 1 24 ferences in mean activity time, preparation time,

Walk 2 4 9 4 0 0 19 number of staff, falls, and unintended tube removals

Total 3 17 58 32 8 2 120 between treatments, a mixed Poisson log-linear count

Standard regression model is applied.13 This model will account

Chair 0 10 44 8 1 0 63 for the skewness inherent in the strictly positive

Dangle 0 0 17 9 1 2 29 data observed (activity and preparation times; staff,

Stand/march 0 3 8 1 0 0 12

fall, and tube removal counts). The model is mixed

Walk 0 4 6 4 0 0 14

Total 0 17 75 22 2 2 118 with a normal random effect to account for repeated

observation of patients. The independent variables

included are treatment (platform/standard) and

type of activity, along with an interaction between

the 2 variables. Analyses were performed by using

Table 3

Activity time, preparation time, and number of SAS version 9.3.

staff by activity type

Mean (SD)

Results

No unintended tube removals or falls were

Variable Platform Standard

recorded, so safety is not addressed further. The data

Activity time, min set included 118 observations of standard activities

Chair 79.07 (68.53) 62.56 (49.30) and 120 observations of platform activities. Table 2

Dangle 8.97 (4.09) 12.20 (7.40) provides descriptive statistics of the activities observed

Stand/march 9.31 (5.39) 19.64 (20.48) for both treatments. The table shows the number of

Walk 39.53 (36.80) 31.25 (40.63)

activities according to the number of staff required,

Total 39.51 (54.05) 41.87 (45.03)

by activity type.

Preparation time, min Activities involved between 0 and 5 staff, with

4.85 (4.51) 3.75 (2.81)

Chair

5.00 (3.39) 4.60 (3.39) 2 staff the most common (133 activities with 2

Dangle

4.39 (2.97) 3.00 (4.22) staff). The type of staff was not included in the study.

Stand/march

3.95 (3.34) 6.31 (5.50)

Walk The ICU nurse is responsible for determining if

4.65 (3.75) 4.17 (3.55)

Total the patient is safe for mobility and to ensure that

No. of staff 2.08 (0.81) 2.00 (0.60) mobility occurs. Of the 238 activities, 60 involved

Chair 2.55 (0.81) 2.59 (0.87) a dangle, 109 progressed to the chair, 38 involved

Dangle 2.58 (1.10) 1.83 (0.58) standing/marching in place, and 33 involved walk-

Stand/march 1.79 (0.92) 2.00 (0.78)

ing. The number of stand/walk activities was greater

Walk 2.26 (0.93) 2.13 (0.73)

Total for the platform (24 activities) than for standard

equipment (12 activities). Similarly, the number

of walking activities was greater for the platform

with the patient’s participation. Bed in chair posi- (19 activities) than for standard equipment (14

tion did not require patients to use their muscles or activities).

actively participate. This stage is a safety check to To assess the effectiveness of the platform,

see if the patient can tolerate mobility without sig- means and standard deviations of activity times by

nificant changes in their vital signs. type of activity, for both treatments, are reported in

Table 3. Both treatments showed large amounts of

Statistical Analysis variation in activity time. Although the standard

Analysis includes a description of the activities equipment showed longer mean activity times for a

observed. The total numbers of activities (activity dangle or a stand/march in place, the mean activity

sample size) for both treatments are reported. Activ- times for a walk was greater for platform patients

ity sample size is further classified according to the (39.53 minutes) than for standard patients (31.25

type of activity and the number of staff required for minutes). Thus the platform may be more effective

each activity. in terms of activity time when patients walk. Using

454 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2014, Volume 23, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

a mixed Poisson count regression (MPCR) model, and workflow in the ICU. The study did not show

accounting for repeated observation of patients and any significantly improved efficiency, effectiveness,

controlling for the effect of different activity types, or safety with the platform compared with standard

no significant difference was found in mean activity equipment, proving to ICU nurses that they can mobi-

time between the platform and standard treatments lize ICU patients with the equipment they have avail-

(P = .62). able. New equipment may be less efficient for the

To assess the efficiency of the platform in terms nurses to use than equipment with which they are

of time, means and standard deviations of prepara- familiar. That possibility, coupled with the low sam-

tion times by type of activity, for both treatments, ple size, could have affected statistical significance.

are reported in Table 3. Although the standard equip- The preparation for the research study provided

ment showed faster preparation times for a sit, dan- training to the ICU nurses in using gait belts to assist

gle, or stand/march, the mean preparation time with mobilizing patients out of bed, thus improving

was shorter for platform patients (3.95 minutes) safety for both staff and patients. The safety check-

than for standard patients (6.31 minutes) who walk. list provided for the nurses to use before activity to

Therefore, the platform may be more efficient in ensure a standard process during the research study

terms of preparation time with patients who walk. could be used in other mobility protocols.

Using another MPCR model, no significant differ- The study validated that the mobility protocol

ence was found in mean activity time between the is safe; there were no falls, unplanned tube removals,

platform and standard treatments (P = .19). or emergency events. Two other studies15,16 report

To assess the efficiency of the platform in terms similar results, an unplanned tube removal rate of

of staff, means and standard deviations of number 0.8% in 1 study,15 and 1 unplanned

of staff by type of activity, for both treatments, are tube removal and no falls in a dif-

reported in Table 3. Use of the platform allowed 3 ferent study of 75 patients.16 Allow- Activity time did

patients to be active without the help of any staff ing the nurses to prove that the not differ signifi-

(1 stand/march, 2 walk), whereas no standard mobility protocol was safe had a

patients were active without the help of any staff. huge impact in changing the cul- cantly between

For patients involved in walking, use of the plat- ture of the ICU. In order to change

form allowed fewer staff to be involved on average culture, the nurses’ perceptions and

the platform

(1.79) than was possible with standard treatment teamwork must be addressed. Dur- and standard

(2.00). This result suggests that the platform may be ing the research study, the nurses

more efficient in terms of required staff with had the opportunity to change their equipment.

patients who walk and in terms of encouraging perception as they witnessed suc-

individual activity. Using another MPCR model, a cessful mobility. A study done by Thomsen et al17 in

marginally significant difference was found in mean 2008 illustrated the importance of culture; the

activity time between the platform and standard strongest predictor of a patient ambulating was the

treatments (P = .08), with the platform showing ICU to which they were admitted. Patients admitted

lower mean staff expected after the differences in to the respiratory ICU, where mobility is a key clini-

mean staff across activity types were accounted for. cal intervention, had a statistically significant increase

in ambulation. Mobilizing ICU patients is demand-

Discussion ing: the ICU nurses must be committed to coordi-

Although the study findings were not statistically nation of care and teamwork. The nurses need to

significant, several very important descriptive statis- see the connection between mobilizing their ICU

tics were discovered. No information documenting patients and the patients’ outcomes.

the resources required to mobilize ICU patients has The research study allowed the ICU nurses to

been published; this study documents the human test the protocol, determine it was safe, define how

resources needed. Most of the time, 2 staff members they would implement the practice, and ultimately

were required to mobilize the patient, with a prepa- to see the difference it made for their patients. Six

ration time of 5 minutes. The most frequent activity months before the research study, the mobility

is getting up and into the chair, and the patient protocol used in the research study had been

stays up approximately 40 minutes. implemented in the ICU; however, practice had

Mobilizing patients to the chair was also the not changed. The goal of the research study was to

most frequent activity in a study conducted by compare equipment needs for mobility, but the

Bourdin et al14 published in 2010. Nurses can use unintended result of the study was a change in the

this information when planning a mobility program individual nurses’ perceptions and beliefs regarding

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2014, Volume 23, No. 6 455

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

mobility. It is unclear what part of the research study as well as recent publications that early mobil-

process created this change: increased education, ity is both safe and feasible. Actualizing a mobility

changes in equipment, the rigor of a research study, protocol does require interruption in sedation or

or a combination of factors. The net result was an nonsedated ICU patients, so that the patient can

improvement in mobility of ICU patients. Although participate. Further research is needed to determine

not reported as part of this research study but tracked the optimal amount of activity for ICU patients.

for quality purposes, the percentage of patients who

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

are mobilized in the ICUs has increased fourfold. None reported.

Similar results were found in a study published by

Drolet et al18: implementation of a nurse-driven

protocol increased ambulation of ICU patients from eLetters

Now that you’ve read the article, create or contribute to an

6.2% to 20.2%, and even bigger increases were seen online discussion on this topic. Visit www.ajcconline.org

in the intermediate unit. The nurses proved to them- and click “Responses” in the second column of either the

full-text or PDF view of the article.

selves the value of early mobility and the value of

bedside research in changing clinical practice. It has

changed the culture not just with mobility but also REFERENCES

1. Bailey P, Thomsen GE, Spuhler VJ, et al. Early activity is

with sedation. Patients have to be awake to partici- feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Crit Care

pate in mobility. Numerous recently published Med. 2007;35(1):139-145. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251130

.69568.87

studies5,19-24 have documented the value of lighter 2. Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, et al. Early physical

sedation of patients undergoing mechanical ventila- medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respira-

tory failure: a quality improvement project. Arch Phys Med

tion. This experience has empowered the nurses to Rehabil. 2010;91:536-542. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.002.

make other decisions about changing their practice 3. Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early

physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated,

to improve patient care. critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet.

2009;373:1874-1882. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9.

4. Winkelman C, Johnson KD, Hejal R, et al. Examining the

Limitations and Strengths positive effects of exercise in intubated adults in ICU: a

Our study had several limitations. It was a sin- prospective repeated measure clinical study. Intensive Crit

Care Nurs. 2012;28:307-320.

gle-site study; however, both medical and surgical 5. Morandi A, Brummel NE, Ely EW. Sedation, delirium and

patients were included in the sample. The study mechanical ventilation: the ‘ABCDE’ approach. Curr Opin

Crit Care. 2011;17:43-49.

lacked a sample size large enough to establish sta- doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283427243.

tistical significance, but the number was adequate 6. Morris PE. Moving our critically ill patients: mobility barriers

and benefits. Crit Care Clin. 2007;23(1):1-14. doi:10.1016

for descriptive statistics. The activity times of selected /j.ccc.2006.11.003.

patients varied, reducing the power of associated 7. Needham DM. Mobilizing patients in the intensive care

unit: improving neuromuscular weakness and physical

tests. Mobility was not correlated with severity of function. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1685-1690. doi:10.1001/jama

illness, use of mechanical ventilation, or sedation .300.14.1685.

8. Truong AD, Fan E, Brower RG, Needham DM. Bench-to-

levels. The sample includes patients receiving mechan- bedside review: mobilizing patients in the intensive care

ical ventilation and patients who were not. Results unit: from pathophysiology to clinical trials. Crit Care

Forum. 2009;13:216-224. doi:10.1186/cc7885.

are not stratified on the basis of severity of illness, 9. Morris PE, Griffin L, Berry M, et al. Receiving early mobility

mechanical ventilation, or sedation levels. Adding during an ICU admission is a predictor of improved outcomes

in acute respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341(5):

this information to future studies would be impor- 373-377. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31820ab4f6.

tant for ICU practice. The study did not address 10. Bailey PP, Miller RR, Clemmer TP. Culture of early mobility

in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:

evaluation of patients’ participation or effort. The S429-S435. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6e227.

scope of the study did not include collection of data 11. Zomorodi M, Topley D, McAnaw M. Developing a mobility

protocol for early mobilization of patients in a surgical/

regarding readmission or post-ICU outcomes. The trauma ICU. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012:1-10. doi:10.1155/2012

study results were not correlated with ICU length /964547.

12. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP,

of stay, days of mechanical ventilation, delirium Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment

rates, or hospital length of stay. These outcomes are method—a new method for detection of delirium. Ann

Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

already well established in published reports, so our 13. Lee Y, Nelder JA, Pawitan Y. Generalized Linear Models With

limited resources were not used for this correlation. Random Effects. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC:2006.

14. Bourdin G, Barbier J, Burle J-F. The feasibility of early

physical activity in intensive care unit patients: a prospec-

Conclusion tive observational one-center study. Respir Care. 2010;55(4):

400-407.

Conducting the mobility research study promoted 15. Pohlman MC, Schweichert WD, Pohlman AS, et al. Feasibil-

both earlier initiation and progression of mobility ity of physical and occupational therapy beginning from

initiation of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2010;

in the ICU. The study demonstrated that a nurse- 38(11):2089-2094. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f270c3.

driven protocol can be effective. It is clear from this 16. Winkelman C, Johnson KD, Hejal R, et al. Examining the

456 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2014, Volume 23, No. 6 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

positive effects of exercise in intubated adults in ICU: a 22. Barr J, Gilles FL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines

prospective repeated measures clinical study. Intensive for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in

Crit Care Nurs. 2012;28:307-320. adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med.

17. Thomsen GE, Snow GL, Rodriquez L, Hopkins RO. Patients 2013;41:263-306. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72.

with respiratory failure increase ambulation after transfer 23. Skrobik Y, Ahern S, Leblanc M, et al. Protocolized intensive

to an intensive care unit where early activity is a priority. care unit management of analgesia, sedation, and delirium

Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1119-1124. improves analgesia and subsyndromal delirium rates.

18. Drolet A, Dejuilio P, Harkless S, et al. Move to improve: the Anesth Analg. 2010;111(2):451-463.

feasibility of using an early mobility protocol to increase 24. Salgado DR, Favory R, Goulart M, Brimiolle S, Vincent JL.

ambulation in the intensive and intermediate care setting. Toward less sedation in the intensive care unit: a prospec-

Phys Ther J. 2012;93(2). doi:10.2522/ptj.20110400. tive observational study. J Crit Care. 2011;26(2):113-121.

19. Kress JP. Sedation and mobility: changing the paradigm. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.11.003.

Crit Care Clin. 2013;29:67-75. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2012.10.001.

20. Strom T, Martinussen T, Toft P. A protocol of no sedation

for critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a

randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9713):475-480.

21. Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, et al. Efficacy and safety of To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact the

a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 101

mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (awaken- Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Phone, (800) 899-1712

ing and breathing controlled trial): a randomized controlled or (949) 362-2050 (ext 532); fax, (949) 362-2049; e-mail,

trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):126-134. reprints@aacn.org.

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, November 2014, Volume 23, No. 6 457

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

Early Mobility in the Intensive Care Unit: Standard Equipment vs a Mobility Platform

Melanie Roberts, Laura Adele Johnson and Trent L. Lalonde

Am J Crit Care 2014;23 451-457 10.4037/ajcc2014878

©2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

Published online http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/

Personal use only. For copyright permission information:

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/cgi/external_ref?link_type=PERMISSIONDIRECT

Subscription Information

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/

Information for authors

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/misc/ifora.xhtml

Submit a manuscript

http://www.editorialmanager.com/ajcc

Email alerts

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/etoc.xhtml

The American Journal of Critical Care is an official peer-reviewed journal of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

(AACN) published bimonthly by AACN, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Telephone: (800) 899-1712, (949) 362-2050, ext.

532. Fax: (949) 362-2049. Copyright ©2016 by AACN. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on September 1, 2019

You might also like

- Early Mobilisation in Intensive Care During Renal Replacement TherapyDocument6 pagesEarly Mobilisation in Intensive Care During Renal Replacement TherapyPERALTA MONTILLA LAURANo ratings yet

- Escala PermeDocument9 pagesEscala PermeMileniNo ratings yet

- JBM 2018051810335812Document7 pagesJBM 2018051810335812ARUN VNo ratings yet

- LS 1134 Rev A Early Mobility and Walking Program PDFDocument10 pagesLS 1134 Rev A Early Mobility and Walking Program PDFYANNo ratings yet

- Early Mobilization in The ICU: A Collaborative, Integrated ApproachDocument8 pagesEarly Mobilization in The ICU: A Collaborative, Integrated ApproachJohn LemonNo ratings yet

- Alarms in The Icu: A Study Investigating How Icu Nurses Respond To Clinical Alarms For Patient Safety in A Selected Hospital in Kwazulu-Natal Province, South AfricaDocument6 pagesAlarms in The Icu: A Study Investigating How Icu Nurses Respond To Clinical Alarms For Patient Safety in A Selected Hospital in Kwazulu-Natal Province, South AfricaPASANTIA UAONo ratings yet

- Barriers and Facilitators To Early Mobilisation in Intensive Care A Qualitative StudyDocument6 pagesBarriers and Facilitators To Early Mobilisation in Intensive Care A Qualitative StudyNatalia Tabares EcheverriNo ratings yet

- 436 2003 1 PBDocument7 pages436 2003 1 PBPASANTIA UAONo ratings yet

- Aorn 12423Document14 pagesAorn 12423Ghassan KhairallahNo ratings yet

- ICU Without WallDocument6 pagesICU Without WallFahmi AuliaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating A Case Study Using Bloom's Taxonomy of Education: ASE TudyDocument10 pagesEvaluating A Case Study Using Bloom's Taxonomy of Education: ASE TudyAli RaufNo ratings yet

- ICU Registered Nurses 3Document9 pagesICU Registered Nurses 311 - JEMELYN LOTERTENo ratings yet

- Movilización y Recuperación Precoces en Pacientes Con Ventilación Mecánica en La UCI Un Estudio de Cohorte Prospectivo Binacional, MulticéntricoDocument10 pagesMovilización y Recuperación Precoces en Pacientes Con Ventilación Mecánica en La UCI Un Estudio de Cohorte Prospectivo Binacional, MulticéntricoByron VarasNo ratings yet

- Early Mobility in The Intensive Care Unit: Evidence, Barriers, and Future DirectionsDocument12 pagesEarly Mobility in The Intensive Care Unit: Evidence, Barriers, and Future DirectionsRaka dewiNo ratings yet

- APA 7th Edition Template Student VersionDocument14 pagesAPA 7th Edition Template Student VersionAndrei ArtiedaNo ratings yet

- Standardised Handover Protocol 2014 PDFDocument7 pagesStandardised Handover Protocol 2014 PDFNikkae AngobNo ratings yet

- Elliott 2011Document12 pagesElliott 2011oscar eduardo mateus ariasNo ratings yet

- Duffy 2023 Oi 230251 1680623455.50534Document10 pagesDuffy 2023 Oi 230251 1680623455.50534Hamilton CeballosNo ratings yet

- Jop 2016 016857Document9 pagesJop 2016 016857andrei vladNo ratings yet

- Betters 2017 Development and Implementation of An Early Mobility Program For Mechanically Ventilated Pediatric PatientsDocument6 pagesBetters 2017 Development and Implementation of An Early Mobility Program For Mechanically Ventilated Pediatric PatientsEvelyn_D_az_Ha_8434No ratings yet

- Spooner 2018Document9 pagesSpooner 2018andremNo ratings yet

- Early Postoperative Ambulation Back To Basics A Quality Improvement Project PDFDocument7 pagesEarly Postoperative Ambulation Back To Basics A Quality Improvement Project PDFIndra MulianiNo ratings yet

- What Are The Barriers To Mobilizing Intensive Care Patients?Document4 pagesWhat Are The Barriers To Mobilizing Intensive Care Patients?Tote Cifuentes AmigoNo ratings yet

- J Ijnurstu 2017 12 012Document8 pagesJ Ijnurstu 2017 12 012Osborn KhasabuliNo ratings yet

- Handling Article 1Document10 pagesHandling Article 1Dusabeyezu PacifiqueNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Ambulatory Surgery - Perioperative Concerns: Dr. Pramila Chari Dr. Indu SenDocument7 pagesPaediatric Ambulatory Surgery - Perioperative Concerns: Dr. Pramila Chari Dr. Indu SenT RonaskyNo ratings yet

- A Simple DeviceDocument6 pagesA Simple DeviceErna TamiziNo ratings yet

- Iwashyna 2016Document2 pagesIwashyna 2016febrian rahmatNo ratings yet

- Early Mobilitation For Critically Ill Patients in ICUDocument34 pagesEarly Mobilitation For Critically Ill Patients in ICUririNo ratings yet

- Journal Ortho RequirementDocument13 pagesJournal Ortho RequirementKenn yahweexNo ratings yet

- A Descriptive Study To Assess The Knowledge Regarding Venipuncture Among Staff Nurses in A Selected Hospital, Lucknow With A View To Develop An Information BookletDocument7 pagesA Descriptive Study To Assess The Knowledge Regarding Venipuncture Among Staff Nurses in A Selected Hospital, Lucknow With A View To Develop An Information BookletEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Mobilitas 5Document8 pagesJurnal Mobilitas 5abdul muisNo ratings yet

- International Emergency Nursing: SciencedirectDocument24 pagesInternational Emergency Nursing: SciencedirectRazak AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Early Post Op. MobillizationDocument21 pagesEarly Post Op. MobillizationGenyNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Early Ambulation On Patient Outcomes For Total Joint ReplacementDocument4 pagesThe Effect of Early Ambulation On Patient Outcomes For Total Joint ReplacementAris PurnomoNo ratings yet

- Intensive & Critical Care Nursing: Research ArticleDocument7 pagesIntensive & Critical Care Nursing: Research ArticleEviNo ratings yet

- Semana 1-Paper, Fundamentals of US in Clinical PracticeDocument14 pagesSemana 1-Paper, Fundamentals of US in Clinical PracticeRudy AravenaNo ratings yet

- Irtual Reality in Research and Rehabilitation of Gait and Balance in Parkinson DiseaseDocument17 pagesIrtual Reality in Research and Rehabilitation of Gait and Balance in Parkinson DiseasePaula EmyNo ratings yet

- Effects of Virtual Reality Training On Functional Reaching Movements in People With Parkinson's Disease: A Randomized Controlled Pilot TrialDocument12 pagesEffects of Virtual Reality Training On Functional Reaching Movements in People With Parkinson's Disease: A Randomized Controlled Pilot TrialVivis Yuvi SamarNo ratings yet

- Original PaperDocument11 pagesOriginal PaperAsmaa GamalNo ratings yet

- Point of Care Ultrasound: The Critical Imaging Tool For The Critically UnwellDocument10 pagesPoint of Care Ultrasound: The Critical Imaging Tool For The Critically UnwellOswaldo OrtizNo ratings yet

- Johnson 2017Document4 pagesJohnson 2017febrian rahmatNo ratings yet

- Tabel AjaDocument7 pagesTabel AjaRainbow DashieNo ratings yet

- PTJ 1636Document10 pagesPTJ 1636Pamela DíazNo ratings yet

- Protocol-Based Mobilization On Intensive Care Units: Stepped-Wedge, Cluster-Randomized Pilot Study (Pro-Motion)Document7 pagesProtocol-Based Mobilization On Intensive Care Units: Stepped-Wedge, Cluster-Randomized Pilot Study (Pro-Motion)Lee Li Nou OkhmachNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness Mobility Protocol Towards Intensive Care Unit PatientsDocument10 pagesEffectiveness Mobility Protocol Towards Intensive Care Unit PatientsMhar IcelNo ratings yet

- Tii 2021 3069470Document9 pagesTii 2021 3069470Gautham SgNo ratings yet

- Critical Care: Queuing Theory Accurately Models The Need For Critical Care ResourcesDocument6 pagesCritical Care: Queuing Theory Accurately Models The Need For Critical Care ResourcesAngela SaoNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Virtual Reality in Research and Rehabilitation of Gait and Balance in Parkinson DiseaseDocument17 pagesReviews: Virtual Reality in Research and Rehabilitation of Gait and Balance in Parkinson DiseaseDuda ShiraiwaNo ratings yet

- Fluid Administration For Acute Circulatory Dysfunction Using Basic Monitoring Narrative Review and Expert Panel Recommendations From An ESICM Task Force Maurizio CecconDocument12 pagesFluid Administration For Acute Circulatory Dysfunction Using Basic Monitoring Narrative Review and Expert Panel Recommendations From An ESICM Task Force Maurizio CecconEllys Macías PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Artigo 2 CinhalDocument7 pagesArtigo 2 CinhalSara PereiraNo ratings yet

- 4-8-1-989 Format For SynopsisDocument7 pages4-8-1-989 Format For SynopsisYashoda SatputeNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Management of Geriatric Patients: Review ArticleDocument22 pagesAnesthetic Management of Geriatric Patients: Review Articleagita kartika sariNo ratings yet

- Identify: Candidates CareDocument10 pagesIdentify: Candidates CareJHNo ratings yet

- Delirium UciDocument6 pagesDelirium UciHernando CastrillónNo ratings yet

- Implementing Early Mobilisation in The Intensive Care Unit - An Integrative ReviewDocument15 pagesImplementing Early Mobilisation in The Intensive Care Unit - An Integrative ReviewfabianneassisNo ratings yet

- Care Unit PDFDocument9 pagesCare Unit PDFsitinafisahNo ratings yet

- Pa Shik Anti 2012Document8 pagesPa Shik Anti 2012Irfan FauziNo ratings yet

- Monitoring the Nervous System for Anesthesiologists and Other Health Care ProfessionalsFrom EverandMonitoring the Nervous System for Anesthesiologists and Other Health Care ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- Keys to Successful Orthotopic Bladder SubstitutionFrom EverandKeys to Successful Orthotopic Bladder SubstitutionUrs E. StuderNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Care in Ed Fast TracksDocument7 pagesEvaluating Care in Ed Fast TracksBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Accuracy of Sepsis-3 Criteria For In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With Suspected Infection Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentDocument8 pagesPrognostic Accuracy of Sepsis-3 Criteria For In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With Suspected Infection Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Turkish Journal of Emergency MedicineDocument4 pagesTurkish Journal of Emergency MedicineBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Improving Emergency Department Patient FlowDocument6 pagesImproving Emergency Department Patient FlowBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Bladder Irrigation in Preventing Urinary Tract Infections Associated With Short-Term Catheterization in Comatose PatientsDocument6 pagesEfficacy of Bladder Irrigation in Preventing Urinary Tract Infections Associated With Short-Term Catheterization in Comatose PatientsBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Quality of Care Delivered by An Emergency Department Fast Track Unit With Both Nurse Practitioners and DoctorsDocument7 pagesEvaluating The Quality of Care Delivered by An Emergency Department Fast Track Unit With Both Nurse Practitioners and DoctorspoppyNo ratings yet

- Impact of A Planned Workflow ChangeDocument12 pagesImpact of A Planned Workflow ChangeBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Accuracy of Sepsis-3 Criteria For In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With Suspected Infection Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentDocument8 pagesPrognostic Accuracy of Sepsis-3 Criteria For In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With Suspected Infection Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Effect of Music On Pain, Anxiety, and Patient Satisfaction inDocument10 pagesEffect of Music On Pain, Anxiety, and Patient Satisfaction inDewi Ji YongNo ratings yet

- Intensive & Critical Care Nursing: Research ArticleDocument7 pagesIntensive & Critical Care Nursing: Research ArticleEviNo ratings yet

- Music in Emergency DepartmentDocument24 pagesMusic in Emergency DepartmentWiryawan AlamNo ratings yet

- 89 452 1 PB PDFDocument19 pages89 452 1 PB PDFpra sethyaNo ratings yet

- Patient Satisfaction and Benefts of Music Therapy Services To Manage Stress and Pain in The Hospital Emergency DepartmentDocument25 pagesPatient Satisfaction and Benefts of Music Therapy Services To Manage Stress and Pain in The Hospital Emergency DepartmentBapak Sunaryo SPBU100% (1)

- Mobilization of Intensive Care Patients A Multidisciplinary Practical Guide For CliniciansDocument10 pagesMobilization of Intensive Care Patients A Multidisciplinary Practical Guide For CliniciansBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- 1495 PDFDocument8 pages1495 PDFSusan Wulandari ApriLiaNo ratings yet

- Patient Early Mobilization A Malaysias Study of Nursing Practices PDFDocument7 pagesPatient Early Mobilization A Malaysias Study of Nursing Practices PDFNuraien LapaleoNo ratings yet

- Working With Art in A Case of SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesWorking With Art in A Case of SchizophreniaBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Working With Art in A Case of SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesWorking With Art in A Case of SchizophreniaBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For The Treatment of Adolescent Depression (Hayes, 2011)Document9 pagesAcceptance and Commitment Therapy For The Treatment of Adolescent Depression (Hayes, 2011)Bapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Visual Hallucination For Computational CreationDocument8 pagesVisual Hallucination For Computational CreationBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Working With Art in A Case of SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesWorking With Art in A Case of SchizophreniaBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Visual Hallucination For Computational CreationDocument8 pagesVisual Hallucination For Computational CreationBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- A Review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Act) Empirical EvidenceDocument39 pagesA Review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Act) Empirical EvidenceBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Art Therapy May Reduce Psychopathology in Schizophrenia by Strengthening The Patients' Sense of SelfDocument6 pagesArt Therapy May Reduce Psychopathology in Schizophrenia by Strengthening The Patients' Sense of SelfBapak Sunaryo SPBUNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study For Determination of Atracurium Besilate in Presence of Its Toxic Degradant (Laudanosine) by Reversed Phase HPLC and by TLC DensitometryDocument11 pagesComparative Study For Determination of Atracurium Besilate in Presence of Its Toxic Degradant (Laudanosine) by Reversed Phase HPLC and by TLC DensitometrySabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- MSDS TSHDocument8 pagesMSDS TSHdwiNo ratings yet

- Know Your Customer BrochureDocument4 pagesKnow Your Customer BrochureTEL COMENo ratings yet

- Manufacturing ProcessesDocument6 pagesManufacturing ProcessesSudalai MadanNo ratings yet

- Jeremiah's Law, Introduced by Assemblywoman Rodneyse BichotteDocument2 pagesJeremiah's Law, Introduced by Assemblywoman Rodneyse BichotteCity & State NYNo ratings yet

- Awsum BrandingDocument18 pagesAwsum Brandingdharam123_904062105No ratings yet

- Compact Water Treatment 200 m3Document3 pagesCompact Water Treatment 200 m3civil eng915No ratings yet

- 1978 - Behavior Analysis and Behavior Modification - Mallot, Tillema & Glenn PDFDocument499 pages1978 - Behavior Analysis and Behavior Modification - Mallot, Tillema & Glenn PDFKrusovice15No ratings yet

- SEI BasicDocument146 pagesSEI BasicYuthia Aulia Riani100% (1)

- Karen Horney's Theories of PersonalityDocument8 pagesKaren Horney's Theories of PersonalityGeorge BaywongNo ratings yet

- Syntheis Writing 2 How Do Fear and Desire For Personal Acceptance Influence Human BehaviorDocument2 pagesSyntheis Writing 2 How Do Fear and Desire For Personal Acceptance Influence Human Behaviorapi-463684021No ratings yet

- To: Head of Sea Training Department PT Gemilang Bina Lintas Tirta Ship ManagementDocument1 pageTo: Head of Sea Training Department PT Gemilang Bina Lintas Tirta Ship ManagementtarNo ratings yet

- Internship-Plan BSBA FInalDocument2 pagesInternship-Plan BSBA FInalMark Altre100% (1)

- Aaos PDFDocument4 pagesAaos PDFWisnu CahyoNo ratings yet

- QTR-2 2023 Meeting Format Nov.23Document45 pagesQTR-2 2023 Meeting Format Nov.23skumar31397No ratings yet

- Blood Stasis and What Does That MeanDocument2 pagesBlood Stasis and What Does That MeanCarl MacCordNo ratings yet

- Formulating A Dental Treatment Plan: DR Tashnim BagusDocument33 pagesFormulating A Dental Treatment Plan: DR Tashnim BagustarekrabiNo ratings yet

- Midterm Requirement-Green BuildingDocument7 pagesMidterm Requirement-Green BuildingJo-anne RiveraNo ratings yet

- Zinc Silicate or Zinc Epoxy As The Preferred High Performance PrimerDocument10 pagesZinc Silicate or Zinc Epoxy As The Preferred High Performance Primerbabis1980100% (1)

- Bio 2Document3 pagesBio 2ganchimeg gankhuuNo ratings yet

- ISO 9001 - 14001 - 2015 enDocument2 pagesISO 9001 - 14001 - 2015 enVĂN THÀNH TRƯƠNGNo ratings yet

- Problems SetDocument10 pagesProblems SetSajith KurianNo ratings yet

- Rozdział 12 Słownictwo Grupa BDocument1 pageRozdział 12 Słownictwo Grupa BBartas YTNo ratings yet

- Executive Compensation: A Presentation OnDocument9 pagesExecutive Compensation: A Presentation On9986212378No ratings yet

- PSV Sizing For Two Phase FlowDocument28 pagesPSV Sizing For Two Phase FlowSyed Haideri100% (1)

- Eisenmenger SyndromeDocument6 pagesEisenmenger SyndromeWarkah SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Access To JusticeDocument9 pagesAccess To JusticeprimeNo ratings yet

- Name of Learner: Section: Subject Teacher: Date:: Practical Research 2Document4 pagesName of Learner: Section: Subject Teacher: Date:: Practical Research 2J-heart Basabas Malpal100% (6)

- Paper 4 Nov 2000Document2 pagesPaper 4 Nov 2000MSHNo ratings yet

- Manual Fritadeira PDFDocument136 pagesManual Fritadeira PDFtherasiaNo ratings yet