Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 195.33.208.242 On Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

Uploaded by

yakartepeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 195.33.208.242 On Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

Uploaded by

yakartepeCopyright:

Available Formats

What Is Symmetry in Music?

Author(s): Davorin Kempf

Source: International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music , Dec., 1996, Vol.

27, No. 2 (Dec., 1996), pp. 155-165

Published by: Croatian Musicological Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/3108344

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Croatian Musicological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (19%) 2, 155-165 155

WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?*

UDC: 781.1

DAVORIN KEMPF

Conference Paper

PriopCenje sa znanstvenog

University of Zagreb, Music Academy, skupa

Received: October 10, 1996

Gundulideva 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

Primljeno: 10. listopada 1996.

Accepted: October 25, 1996

PrihvaCeno: 25. listopada 1996.

Abstract - R&sum=

Through the history of music - in various tions within a compositional wholeness; 2) The

musical forms and styles - it is possible to rec- so-called mirror symmetry, the mirror reflection

ognize some universal principles. One of them of a micro- or macro-formal structure around a

is symmetry, a specific aspect of repetition. There vertical or a horizontal axis, as well as vertical

are various ways of its realization in musical and horizontal axes simultaneously.

structure and form, as well as presuppositions Symmetry is mostly broken in various

of its application, concerning different ways. The main reason for small or strong

compositional systems and styles. Here are two violation of symmetry is the fact that the

basic ways in which symmetry is realized: 1) The mathematical and musical logic are not nec-

symmetrical arrangement of formal parts or sec- essarily compatible.

Music is the art essentially associated with the dimension of time. Its formal

structure may be defined as a specific articulation of time. The most important,

fundamental compositional principle, a kind of archetype of formal idea in music,

is repetition and variation (or varied repetition). Repetition requires contrast and

- vice versa - contrast demands repetition. Articulation of musical form can

hardly be imagined without some sort of identity.

Symmetry is a specific aspect of repetition. There are various ways of its reali-

zation in musical structure and form, as well as presuppositions of its application,

concerning different compositional systems and styles.

* Conference paper read at the 23rd ABI/IBC International Congress on Arts and Communica-

tions, San Francisco, U.S.A., June 30 - Juli 7, 1996.

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

156 D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2,155-165

Regarding the dimension of time, there are two basic ways in which symme

try is realized. The first is in the domain of succession of formal parts or sectio

and appears as their symmetrical arrangement within a compositional wholenes

The second is the so-called mirror symmetry, that may also be applied to a micr

and macroformal structure. It is a matter of a closed system consisting of tw

parts. The second part is a mirror reflection of the first one. In other words, in the

course of musical time, after the imagined vertical axis, we are listening to t

retrograde version of the music that we have just heard in its original version.

As regards the first aspect, i.e. a symmetrical arrangement of formal parts, the

most important, wide-spread symmetrical pattern A-B-A, should be mentione

first of all. It appears frequently in various realizations, not only in music but a

in other arts like architecture, film etc. After the interpolated, more or less contras

tive middle section, the music of the opening section, reappears as a recapitul

tion. It is to be found in piano-miniatures and (art) songs, especially from the ep

och of Romanticism, in the three-part song forms of classical instrumental mus

in arias - first of all in >>da capo<< arias from the Baroque era, then in the three-par

formal variants of classical Menuetts and Scherzos that represent a kind of sym

metry in symmetry etc... The exposition, development and recapitulation of s

nata form follows the same formal pattern, but in a more complex and specif

way, associated with a dialectical process. The tonal, harmonic tension between

the first and second theme (T-D, thesis-antithesis), is overcome (after a develop

mental process of synthesizing) in the recapitulation synthesis, that belongs com

pletely to the tonic key. In the case of the so called >>subdominant recapitulation

(e.g. W.A. Mozart: Sonata Facile) the typical tonal disposition of exposition, toni

- dominant, remains, but the whole first part of >sonata allegro formn is bei

transposed, so that the recapitulation begins in the subdominant and ends in th

tonic key. A very similar procedure was already used by J.S. Bach within the fo

mal concept of his Two-part Invention No. 8, F-major. In such cases the symmet

is conserved, or, alternatively, there is only a small violation of symmetry, and the

symmetrical attraction between exposition and recapitulation increases throug

the tonal-harmonic interrelations:

SD

T T.

SD

Concerning the chorale tradition, with special regard to the polyphonic set-

tings of the ordinarium missae, a symmetrical formal disposition has often re-

sulted from the structure of the text. For example: Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison,

Kyrie eleison. Or >Hosanna in excelsis!<< - at the end of Sanctus, and after that

>>Benedictus que venit in nomine Dominic<, and then again >Hosanna in excelsis!<<.

In his Mass ofNotre DameGuillaume de Machaut follows the idea of symmetrical

ternary form A-B-A within the initial triple exclamation of >Sanctus(, as well as in

the 5th movement Agnus Dei - symmetrical around the center, so that the first

and third formal sections are musically identical. The isorhythmic structure, with

the same numerical proportions (taleae) represents a complex system of symmetries

by itself.

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2, 155-165 157

A literal recapitulation occurs infrequently. Usually there are certain modifi

cations by the reappearance of opening sections. In other words there are small o

strong violations of symmetry. Among many different possibilities here is a ver

special one: The first movement of Webern's Symphony op. 21. The opening four

part double canon in contrary motion, reappears at the end in another rhythmic

version, and with a two-part canonic appendix that closes the movement.

Larger formal complexes with more than three symmetrically distributed parts,

are mostly based on the A-B-A formal pattern. In his 7th Symphony Ludwig va

Beethoven extended the usual 3-part form of Scherzo (Scherzo-Trio-Scherzo) to

5-part form A-B-A-B-A by means of repetition of the second and third parts t

gether. As a matter of fact, this is the formal pattern of the classical rondo with tw

themes, in which the leading theme is repeated, alternating with the second. Her

are some other similar formal successions symmetrical around the center

Couperin's rondeau with couplets, a classical rondo with one theme with the fol

lowing formal plan: Thematic section - 1st episode - thematic section - 2n

episode - thematic section with a Coda, then a classical rondo with three themes

as well as a synthesis of sonata and rondo form A-B-A-C-A-B-A. (The letters,

course, represent the thematic sections.)

The latter 7-part formal type, symmetrical around the central section C, is

very strictly followed by Robert Schumann in his Aufschwung, No. 2 from t

Fantasiestiicke for piano op.12. The idea of rondo with one theme is used by Igo

Stravinsky in the Dance Sacrale from The Rite of Spring. A very free realization

a rondo-conception is to be found in Richard Strauss's tone poem Till Eulenspieg

etc... In the latter two examples there is a strong violation of symmetry.

The idea of rondo form with its symmetrical balance, was already anticipated

in mediaeval Gregorian chant. A symmetry may also be recognized in a >>rainbo

shape( of choral melodies.

Very similar to the idea of classical rondo with one theme is the idea of Ba-

roque >ritornello(, that mostly appears in opening movements of solo concerto

and concerto grosso. While the reappearances of the main, thematic section in th

course of a classical rondo do not leave the tonic key, in the Baroque >ritornello

they modulate to other keys, related to the tonic one. As they are usually varied

various ways, symmetry is broken in the domain of musical structure.

In the realm of the Baroque fugue, there are also interesting examples of

similar symmetrical articulation of formal structure. In the Fugue No. 7, F-mino

from the 1st book of Bach's Wohltemperiertes Kla vier, the main, thematic sections

are represented by the polyphonic developments of the chromatic subject, whil

the interpolated transitional sections are completely diatonic and based on the

>motive of joy( from Bach's cantatas.

Another sophisticated example of symmetrical formal construction is Bart6k

Piano Concerto No. 2, a cross between the Romantic virtuoso showpiece 'a la Lisz

and Bachian refined type of Concerto grosso. Here is the formal plan of the 1

movement, Allegro: A-B-A' C-A"-C' A'- (Cadenza)-B'-A(=Coda). The letters d

note sections corresponding in form or content. The piano cadenza - interpolate

between the 7th and 8th section - as well as the varied reappearances of particu-

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

158 D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2, 155-165

lar sections, represent various aspects of violation of symmetry. Symmetry

also be broken by taking away a formal part, as is the case in the last movem

Allegretto from Mozart's piano sonata D-major, Kochel No. 576. Instead of a r

lar sonata rondo form its formal plan is: A-B-A-Development-B-A. The reason

this compositional procedure lies obviously in the similarity of the 1st and

theme.

There are also other possibilities of symmetrical relations. For instance in Bach

cantatas symmetry is sometimes realized only on the level of succession of

ruses, arias, rezitativos, i.e. various musical numbers, without repetition of

music already heard. In the 7-part formal succession of the cantata Hal

Gediichtnis Herr Jesu Christ the central No. 4 is a Chorale sung by a choir, N

and 5 are the alto rezitativos, Nos 2 and 6 are arias (tenor and bass), No. 1 is a chor

fugue (choir) and No. 7 is the Chorale >>Du Friedefiirst Herr Jesu Christ<< (Ch

An interesting example, how a succession of movements in a cyclic form

by arranged symmetricaly, is a five-movement bridge-form used by Bla Bart

his 4th String Quartet, or by Paul Hindemith in his 3rd String Quartet. Bart6k ma

have taken the model from Beethoven's C-sharp minor Quartet op. 131. The ou

pillar movements are connected by a cyclic principle, while the relationship

tween the second and fourth movements rests on the principle of variation.

Although a simple, immediate repetition of a musical phrase, sentence or

other formal section, that frequently appears in Classical and Romantic mu

especially in Mozart and Schumann - is immediately experienced as symmet

by a listener, the impression of binary symmetry is enforced, when the endi

i.e. cadences of two complementary passages are different, and possess cert

harmonic interrelation, as is the case in the Classical period anticipated in Bar

music and taken over by Romanticism. Paradoxically, such a violation of sym

try enforces - through the harmonic attraction - the coherence and unity of

two-part formal wholeness.

A specific kind of binary symmetry appears when the first of two comp

mentary sections begins with a tonic and ends with a dominant, while the se

one begins with a dominant and ends with a tonic. In the stratum of funct

harmonic relations, a mirror symmetry is already applied here. Here are a

musical examples: The two complementary two-measure phrases at the beginn

of Beethoven's Piano sonata op. 2, No 3 in C-major, as well as at the beginnin

Mozart's Piano sonata G-major, K6chel number 283. Similar formal-harmoni

terrelations applied to a polyphonic musical structure, appear in the exposit

of the C-major fugue No. 1 from Bach's Well Tempered Piano, with the follo

disposition of thematic entries: Dux-Comes Comes-Dux, T-D D-T. Three of t

four chief dance forms of the Baroque suite - Allemande, Courante, Gigue

composed according to the principle of binary symmetry, as well as a large numbe

of D. Scarlatti's sonatas for harpsichord. The dominant ending of the 1st and

beginning of the 2nd formal part are sometimes supstituted by tp (tonic para

As regards such a kind of bilateral symmetry in musical structure and f

that appears as a result of mirror reflection around an axis, first of all the m

symmetry around a vertical axis should be discussed. This aspect is most inte

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2, 155-165 159

ing regarding the dimension of time and musical consequences. As a representa-

tion of a movie in reverse, contrary direction may produce very strange happen-

ings and undesirable comical effects, or else the meaning of the text may be com-

pletely destroyed by reading it backwards. Not every composition or one of its

parts or fragments can be played backwards without disturbing the musical sense

without more or less terrible compositional and aesthetical consequences, espe-

cially in tonal music. What is it that makes an application of this compositional

procedure so extremely difficult and complicated in the realm of traditional, tona

music? First of all, the system of keys, the major and minor key, associated with

the principles of functional classical harmony that also partly determine the shap-

ing of a melodic line, then - in polyphonic music - the strict rules of treatment o

dissonance associated with metrical accents and rhythmical structure, etc. By them-

selves they represent a wonderful system of laws, symmetries, immanent logic

and aesthetical norms that should be respected and followed in a tonal composi-

tion. For instance a typical classical harmonic progression with regular succession

of functions would be T D/SD SD D/D D T. Its retrograde version T D D/D

SD D/SD T is not only unusual but impossible because it does not follow certain

fundamental laws of classical harmony. Or - what about the basic compositional

and aesthetical principle of treatment of dissonance on the accented beat, if the first

beat of a bar becomes the last and unaccented one?! A simple conclusion would be

that the theoretical and practical possibilities of application of mirror symmetry around

a vertical axis are very limited in tonal music. It is not surprising that the realizations

of such a mirror symmetry appear only sporadically in the history of tonal music, an

exclusively in a formal microstructure or short pieces or movements.

Here are a few examples from polyphonic and homophonic music: First of all

the well known Rondeau Ma fin est mon commencement (My end is my begin-

ning) from Ars nova, composed by Guillaume de Machaut for two tenors and

contratenor. After the vertical axis of symmetry in the middle, the whole second

part of the Rondeau is a literal retrograde repetition of the first one. Only the tenor

voices interchange their positions i.e. melodic lines: the 1st becomes the 2nd and

the 2nd becomes the 1st. It is interesting to mention that the original and retro

grade versions of such a piece are equal. (Another vertical axis may be put at the

end of the last bar and the whole composition may be performed backwards.)

The idea of retrograde imitation or canon is based on the same principle. It

appears in the 15th-century Renaissance vocal polyphony in the Netherlands, Ba-

roque instrumental polyphony in Germany, etc. - In his Musical Offering BWV

1079, among various canons, J.S. Bach wrote a two-part retrograde canon in C-

minor (Canon cancrizans BWV 1079.3a), using the theme of King Frederic the Great.

A beautiful example from classical homophonic music is Menuetto al Rovescio

from Haydn's Piano sonata in A-major (Hob.: Group 16, No. 26). Each of the 8-

measure sentences of its balanced ternary form A-B-A (Menuetto-Trio-Menuetto

da capo) is immediatelly repeated retrogradely. The result is a complex of interre-

lated symmetries.

Because of the reasons already mentioned in Bach's collections of fugues

Woh1temperiertes Klavier and Die Kunst der Fuge, there are no examples of fugue

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

160 D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2,155-165

or their parts being symmetrical around the vertical axis. Even a retrograde

of a fugal theme is out of the question. Only exceptionally, and only in microform

structure or stratum, such a mirror symmetry can appear.

But in Hindemith's Ludus tonalis, the 20th century pendant of th

Woh1temperiertes Klavier, composed in a system of expanded tonality and

contrapuntal style with emancipated dissonance, the mirror symmetry divid

by means of a vertical axis in the middle of the 2nd development - the Fug

in F into two symmetrically interrelated parts, aesthetically and stylistically

sistent and coherent. The freely added contrapuntal lines at the end of the fu

can be observed as a musically justified violation of symmetry.

In the middle formal section Ricercar II of his Cantata, Igor Stravinsky

plies the mirror reflection around the vertical axis in the stratum of the m

line. All the intervals and rhythms of the theme are symmetrical around t

central dividing line.

It is understandable that in the world of atonality there are many exampl

mirror reflections in musical structure and form, especially in Webern's late

In the 1st movement of his Variations op. 27 for piano there are many >local<< ve

tical axes of symmetry. The 2nd part of the 1st movement of Symphony op.

symmetrical around the middle vertical axis. An interesting example of four-

double retrograde canon is the 18th piece Der Mondfleck from Sch6nberg's Pi

Lunaire. As the rhythms do not coincide the result is a kind of polyrhythm.

As has already been shown by Haydn's Menuetto al Rovescio, a symmet

arrangement of formal sections in the course of musical time can be comb

with a mirror reflection around the vertical axis or axes. Here is another ex

of such a synthesis: Alban Berg's Lyric Suite, 3rd movement. The outer polyp

sections are not only symmetrical regarding the ternary A-B-A formal conc

but also regarding an imagined vertical axis. In other words, the third section

literal retrograde recapitulation of the first one. Because of the interpolated f

composed homophonic central section the procedure may be denoted as a po

poned mirror.

A very important aspect of mirror symmetry in musical structure and form

mirror reflection around a horizontal axis. First of all in the polyphonic music. T

simple imitation or canonic imitation can be comprehended and experienced

sort of symmetry, because of the translation in pitch and time. This basic p

phonic compositional procedure is the starting point of a very complicated sy

of interrelated symmetries, mathematical proportions and geometric shapes i

exposition of the double fugue Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison from Mozart's

uiem. As the system is so ideal, and the polyphonic structure so plastic and t

parent, the effect of symmetry experienced in the course of listening to this mu

is very strong. As for the impression of symmetry and canonic procedure, a

canon and a Baroque sequence should be mentioned here, as well as a canon

employs invertible counterpoint (J.S. Bach: The Two-part Invention No. 2, C-

nor). In addition, here is an application of canonic imitation on a homophon

chordal structure (Orlando di Lasso: The Echo from Libro di Villanelle, Mor

et altri canzoni, Paris 1581.)

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2, 155-165 161

Meanwhile, a real mirror reflection around a horizontal axis of symmetry

means inversion. A melody is inverted when ascending intervals are made to de-

scend by the same degree, and vice versa. Its rhythmical structure remains the

same. Very rarely, the original and inverted versions of a theme or melodic frag-

ment appear simultaneously together - as can be found in the D-minor fugue

from the 1st book of Bach's Wohltemperiertes Klavier or at the end of the 1st move-

ment of Bart6k's Music for String Instruments, Percussion and Celesta. Usually

there is an imitative procedure that implicates a time distance ranging from more

or less close stretto imitation to habitual imitation, when the inverted theme enters

after the original one.

The imitative procedure may be associated with diminution or augmenta-

tion. From this point of view Bach's two-part Canon per Augmentationem in

Contrario Motu from The Art of Fugue is particularly interesting. It employs the

technique of invertible counterpoint in octave associated with the idea of a binary

canonic form.

Paul Hindemith divides his Fugue in Des from Ludus tonalis into two pro-

portionally balanced parts, applying the symmetry around a horizontal axis, so

that the 2nd part is a complete inversion of the first one plus a freely composed

cadenza. But there is only a small violation of symmetry there.

That the procedure of inversion, or mirror reflection around a horizontal axis,

can be applied to the whole polyphonic form of the fugue is proved by J.S. Bach.

His Art of Fugue contains two masterpieces of this kind. First of all this is the

4-part fugue entitled simply Contrapunctus inversus. The complete polyphonic

structure of the original fugue was firstly reflected around a horizontal axis and

then translated in time. That means that the original version of the fugue is fol-

lowed by its inverted version. A simultaneous performance is not possible.

Among many various examples of mirror symmetry around a horizontal axis in

the realm of atonal music here is a special one: The opening 4-part double canon in

contrary motion from Webern's Symphony op. 21. In the canonic pairing of the pri-

mary and inverted sets there is a symmetrical relation between the sets. The matched

sets as well as the whole tone-system are symmetrically deployed around the axis

note >a<<. But the resulting pointillistic, almost serial musical texture is very difficult

for a listener to follow in order to grasp the symmetrical conception or to hear the

separate tones - or small groups of tones - as a part of immanent lines or a complex

of dodecaphonic series used in the canonic compositional process.

The idea of mirror symmetry around a horizontal axis and the proportion of

GS (golden section) lead Bart6k to the formal conception of the first movement of

his Music for String Instruments, Percussion and Celesta. It is a freely composed

fugue with a series of imitative entries of the chromatic theme, arranged according

to a symmetrical pattern of ascending and descending fifths. The axis tone and

main tonal centre is >a<< and the climax tone and the most distant tonal region is E-

flat, attained approximately at the golden section.

Very interesting interrelations between the golden ratio that represents a dy-

namic principle and growth, and symmetry which represents a static principle

and stability, exist in the proportions of formal structure of Debussy's music, e.g.

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

162 D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2, 155-165

in Images and La mer. It is not only an analytical abstraction. The dialogue

tween the dual elements of GS and symmetry at the beginning of the Dialog

vent et de la mer is musically very audiable.

The chordal structure may also be built according to the principles of sym

try. Concerning the classical harmony, there is a group of chords, whose int

structure is symmetrcal around an imagined or actually sounding horizonta

the diminished seventh chord, augmented triad, >>French sixth< etc.

Symmetry can be found in the harmonic system based on the interval of fou

used by Skrjabin, Schoenberg and others.

Of course, in the field of expanded tonality and atonality (whether fr

dodecaphonic or serial) there are numerous possibilities of composing the

cal, harmonic structure symmetricaly. Among many others, Joachim Blum

been very interested in these possibilities. His Sonata No. 3 (Protuberanzen

organ abounds in such symmetrical harmonies. The cluster-structures of Th

devoted to the victims of Hiroshima reveal that Penderecki spontaneously

the mirror symmetry.

A freely composed dissonant atonal harmony can be compounded by tw

more symmetrical chordal components. In Kelemen's string quartet Motion

are two interesting examples of such type (bars 219 and 229).

As regards an organized dodecaphonic-serial atonality, mention should

made here of the complex of symmetries applied to the vertical sound com

performed by strings in the 5th Variation of 2nd movement from Weber

Symphony op. 21.

Mirror reflection around vertical and horizontal axis may be combined in var

ous ways. In his percussion piece BallFall Donald Martin Jenni uses - as a s

ing point - the natural rhythmical succession of a ball falling. This basic m

appears both in original and retrograde versions as well as in diminutio

augmentation, associated with a multi-layered course of time. It is a kind of rhy

mical counterpoint of three separately articulated compositional strata, ac

cally determined by the choice of three groups of percussion instruments:

skin, metal.

A synthesis of both aspects of mirror symmetry, i.e. around a vertical and

horizontal axis simultaneously, is perhaps the most sophisticated way of the reali-

zation of symmetry in music. Almost automatically it is intergrated in the

dodecaphonic system. One of the four basic variants of a twelve-tone row is a

retrograde inversion of the primary set that can be transposed to all of the twelve

pitches of a chromatic scale.

The most complex system of symmetrical interrelations of various kinds in

the area of the 12-tone row is created by Anton Webern in the twelve-tone row of

his String Quartet op. 28, which is based on the 4-tone modus B-A-C-H.

One of the most complicated systems of various symmetries in dodecaphonic

musical structure and form, including the application of retrograde inversion, was

composed by Anton Webern in the 2nd movement Variations of Symphony op.

21. Its formal structure reveals a complex system of symmetries in symmetries.

The mirror reflections around the vertical and horizontal axes used in particular

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2,155-165 163

divisions of the 1st part of this composite double retrograde four-part canon a

symmetricaly interrelated with those in the second part.

Regarding the field of expanded tonality, a very beautiful example of applic

tion of simultaneous mirror reflection around both the vertical and horizontal axis

can be found in Hindemith's Ludus tonalis. The symmetrical conception of the

whole work culminates in symmetrical interrelations between the Prelude and the

Postlude. The Postlude is the Prelude played retrogradely and upside-down. The

horizontal axis >goes< through the tones of C and C-sharp, written on the second

ledger line above the staff (treble clef), as well as on the second ledger line below

the staff (bass clef). The succession of tonal centres of the twelve 3-part fugues,

linked by interludes, is arranged symmetrically around the first and main tonal

centre C. The last, 12th fugue is written in F-sharp. While the Postlude leads the

tonality back from F-sharp to C, the Prelude leads it from C to F-sharp. The final

low tone, great C-sharp at the beginning of the Preludium, becomes the high,

three-lined C-sharp at the beginning of the retrogradely inverted Postludium.

In the complete formal plan, the Postludium is a postponed double mirror. It

is understandable that in the tonal system of major and minor keys associated

with the laws of tonal counterpoint and classical harmony there are no such exam-

ples of realization of symmetry.

Although a diagonal symmetry does not have a great importance in the ar-

ticulation of musical form, it does appear sporadically, mostly in formal micro-

structure. Here is an example from Bach's music: The Two-part Invention No. 6, in

E-major. Both the subject and its countersubject are based on the idea of scale. The

beginning is characterized by )>motus contrarius<< between the subject and coun-

tersubject and the application of invertible counterpoint. The descending thematic

and ascending contrapuntal melodic lines cross in the middle point, the one-lined

tone oe<, diagonally.

This paper is a short survey of various ways of realization of symmetry in

musical structure and form, associated with polyphonic and homophonic music,

tonality, expanded tonality and atonality. Through the history of music - in vari-

ous musical forms and styles - it is possible to recognize some universal princi-

ples. One of them is symmetry. Its ideal or literal realization appears very seldom,

especially in tonal music. Symmetry is mostly broken in various ways. The main

reason for small or strong violation of symmetry is the fact that the mathematical

and musical logic are not necessarily compatible. The presence of symmetry,

achieved consciously or unconsciously, conserved or broken, guarantees nothing.

Only in traces of a genial creative act, there is an ideal synthesis of all components

relevant for great art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BERNSTEIN, Leonard: Young People's Concerts, Simon and Schuster. New York 19

BLUME, Joachim: Komposition nach der Stilwende, M6seler Verlag, Wolfenbilttel und

1972.

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

164 D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2,155-165

BOULEZ, Pierre: Boulez on Music Today,Originally published as Musikdenken Heute

B. Schott's S6hne, Mainz 1963, and Penserla Musique A ujourd'hui, Paris 1963. Eng

translation 1971, Faber and Faber.

BOULEZ, Pierre: Werkstatt-Texte (Translated by Josef Hiiusler), Propylaen Verlage Ul

GmbH, Frankfurt/M-Berlin 1972.

BUKOFZER, Manfred F.: Studies In Medieval and Renaissance Music, J.M. Dent and

Ltd, London.

CALDWELL, John: Medieval Music, Hutchinson, London 1978.

DAVID, Johann Nepomuk: Die Zweistimmigen Inventionen von J.S. Bach, Gottingen

DAVID, Johann Nepomuk: Die Dreistimmigen Inventionen von J.S. Bach, Gottingen 1

DEPPERT, Heinrich: Studien zur Kompositionstechnik im Instrumentalen Spatwerk A

Weberns, Edition Tonos, Darmstadt 1972.

Die Reihe, Wien-Ziirich-London, hrsg. von Herbert Eimert unter Mitarbeit von Karlh

Stockhausen, No 3: Musikalisches Handwerk, 1957; No 4: Junge Komponisten, 1

No 7: Form - Raum, 1960.

ERPF, Hermann: Form und Struktur in der Musik, Schott's S6hne, Mainz 1967.

HOWAT, Roy: Debussy in Proportion, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

KARPATI, Jinos: Bart6k's String Quartets, Franklin Printing House, Budapest 1975. (

Hungarian edition 1967.)

KELLER, Hermann: Das Wohltemperierte Klavier von J.S. Bach, DTV, Biirenreiter--V

Kassel 1965.

KEMP, Jan: Hindemith, Oxford University Press, London-Oxford-New York.

KEMPF, Davorin: Application od Contrapuntal Techniques in 20th Century Music (script),

1984.

KEMPF, Davorin: A series of brodcasts on Croatian radio, 3rd Program 1993-1995, includ-

ing the following thematic cycluses: Repetition and Variation as Compositional Prin-

ciple, Symmetry in Music, Ordinarium Missae Through the History of Music etc.

KERMAN, Joseph: The Beethoven Quartets, Oxford University Press, London-

Melburne-Cape Town. (First published 1967.)

KLOIBER, Rudolf: Handbuch des Instrumental-Konzerts, Band I: Vom Barock bis zurKlassik,

Breitkopf and Hirtel, Wiesbaden 1972.

MARTENS, Heinrich: Musikalische Formen in historischen Reihen, Band 17: Der Kanon,

Chr. Friedrich Vieweg G.m.b.h., Berlin-Lichterfelde.

MESSIAEN, Oliver: Technik meinermusikalischen Sprache(Translated by Sieglinde Ahrens),

1. Band: Text; 2. Band: Musikalische Beispiele, Alphonse Leduc, Paris 1966.

Musik-Konzepte, Heft 9: Alban Berg - Kammermusik, 1979; publ. by Heinz-Klaus Metzger

and Rainer Riehn.

REESE, Gustave: Music In the Renaissance, W. W. Norton, New York 1959.

ROSEN, Charles: The Classical Style (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven), The Viking Press, New

York 1971.

SCH(ONBERG, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony, ed. by Leonard Stein. First pub-

lished in 1954 by Williams and Horgate Limited.

SCHWEITZER, Albert: J.S. Bach, Breitkopf and Hiirtel, Wiesbaden 1952.

STOCKHAUSEN, Karlheinz: Band 1: Texte zur elektronischen und instrumentalen Musik;

Band 2: Texte zu eigenen Werken zur Kunst Anderer, Aktuelles, M. DuMont Schauberg,

K61n 1964.

YOUNG, Percy M.: The Choral Tradition. A Historical and Analytical Survey From the

Sixteenth Century to the Present Day, W.W. Norton, New York 1971.

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

D. KEMPF, WHAT IS SYMMETRY IN MUSIC?, IRASM 27 (1996) 2, 155-165 165

Satetak

SIMETRIJA U GLAZBI

Glazba je umjetnost bitno povezana s dimenzijom vremena. Temeljni kompozicijski

principi su ponavljanje i varijacija (tj. varirano ponavljanje). Simetrija je specifi!ni aspekt

ponavljanja. Postoje razliciti natini realizacije simetrije u glazbenoj strukturi i formi, te

razlidite pretpostavke za njezinu primjenu u svezi s kompozicijskim sustavima i stilovima

kroz glazbenu povijest. Tu se prvenstveno misli na tonalitetnost, progirenu tonalitetnost i

atonalitetnost, te estetiCke implikacije na relaciji matematika (geometrija) - muzika.

Generalno uzevgi postoje dva osnovna aspekta realizacije simetrije na glazbenom

mikro i makroformalnom podruju:

1) simetrija u rasporedu formalnih sekcija, dijelova, ili stavaka - u cikliCkim oblicima;

2) zrcalna simetrija: zrcaljenje po vertikalnoj, horizontalnoj i dijagonalnoj osi simetrije,

ukljueujud i kombinacije kao 6to je retrogradna inverzija.

Idealna, tj. doslovna realizacija simetrije rijetko se pojavljuje, napose u tonalitetnoj

glazbi. Glavni razlog za manja ili veda odstupanja od simetrije leti u dinjenici da se

matematiCka i glazbena logika ne moraju nu2no podudarati. Simetrija sama po sebi ne

implicira umjetniCki doseg, tj. estetiCku vrijednost. Idealnu sintezu svih komponenata

relevantnih za veliku umjetnost dosegli su samo geniji.

This content downloaded from

195.33.208.242 on Thu, 24 Mar 2022 10:09:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Armonia OttatonicaDocument18 pagesArmonia Ottatonicabart100% (1)

- Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony. A Soviet Artist's ReplyDocument7 pagesShostakovich's Fifth Symphony. A Soviet Artist's ReplyBoglarka Szakacs100% (2)

- University of California Press American Musicological SocietyDocument22 pagesUniversity of California Press American Musicological Societykonga12345100% (1)

- Bonds&Cook Musical FormDocument15 pagesBonds&Cook Musical Formuyui2018100% (1)

- The Diminutions in Composition and Theory of Composition - Author(s) - Imogene HorsleyDocument31 pagesThe Diminutions in Composition and Theory of Composition - Author(s) - Imogene Horsleyeugenioamorim100% (1)

- Fisk PerformanceAnalysisMusical 1997Document15 pagesFisk PerformanceAnalysisMusical 1997montserrat torrasNo ratings yet

- A Lesson From Lassus (P. Schubert) PDFDocument27 pagesA Lesson From Lassus (P. Schubert) PDFanon_240627526No ratings yet

- Discant, Counterpoint, and HarmonyDocument22 pagesDiscant, Counterpoint, and Harmonytunca_olcayto100% (2)

- The Evolution of A Memeplex in Late Moza PDFDocument42 pagesThe Evolution of A Memeplex in Late Moza PDFJhasmin GhidoneNo ratings yet

- Sonata Form - WikipediaDocument13 pagesSonata Form - WikipediaElenaNo ratings yet

- Review of Peter Schubert's "Modal Counterpoint"Document5 pagesReview of Peter Schubert's "Modal Counterpoint"Mary Osborn100% (1)

- Tonal and Motivic Process in Mozart's Expositions Scott L. BalthazarDocument47 pagesTonal and Motivic Process in Mozart's Expositions Scott L. BalthazarSebastian Hayn100% (1)

- Oxford University Press Music & Letters: This Content Downloaded From 217.138.75.227 On Wed, 11 Dec 2019 15:03:02 UTCDocument20 pagesOxford University Press Music & Letters: This Content Downloaded From 217.138.75.227 On Wed, 11 Dec 2019 15:03:02 UTCbennyho1216No ratings yet

- Africa RythmsDocument20 pagesAfrica RythmsDavid Espitia Corredor100% (2)

- Article Physics Chopin Etudes Final PDFDocument15 pagesArticle Physics Chopin Etudes Final PDFMassimo BlasoneNo ratings yet

- Society For Music Theory Music Theory SpectrumDocument27 pagesSociety For Music Theory Music Theory Spectrumbogdan424100% (1)

- Physics and Music: Essential Connections and Illuminating ExcursionsFrom EverandPhysics and Music: Essential Connections and Illuminating ExcursionsNo ratings yet

- Period (Music) - WikipediaDocument6 pagesPeriod (Music) - WikipediaDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- Timbre in 20th CenturyDocument21 pagesTimbre in 20th CenturyAditya Nirvaan Ranga100% (1)

- Sonata Form - WikipediaDocument16 pagesSonata Form - WikipediaJohn EnglandNo ratings yet

- Classical CadenzaDocument34 pagesClassical CadenzaarpgoNo ratings yet

- Chapter2 - Timbre and Structure in Tristan Murail's DésintégrationsDocument89 pagesChapter2 - Timbre and Structure in Tristan Murail's DésintégrationsCesare AngeliNo ratings yet

- Lutoslawski's Linear Solo String WritingDocument14 pagesLutoslawski's Linear Solo String WritingWilly Sánchez de CosNo ratings yet

- Her Syntax and Style - Rhythmic Patterns in The Music of Ockeghem and His Contemporaries (Ockeghem Volume 1998)Document13 pagesHer Syntax and Style - Rhythmic Patterns in The Music of Ockeghem and His Contemporaries (Ockeghem Volume 1998)Victoria ChangNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Background of MozartDocument20 pagesAnalysis and Background of MozartAnonymous BBs1xxk96VNo ratings yet

- Thea Musgrave's Clarinet ConcertoDocument4 pagesThea Musgrave's Clarinet ConcertoRomulo VianaNo ratings yet

- The Genesis of A Specific Twelve-Tone System in The Works of VarèseDocument25 pagesThe Genesis of A Specific Twelve-Tone System in The Works of VarèseerinNo ratings yet

- Toward A "Global" History of Music TheoryDocument41 pagesToward A "Global" History of Music TheoryMiguel CampinhoNo ratings yet

- Steven Block - Pitch-Class Transformation in Free Jazz PDFDocument24 pagesSteven Block - Pitch-Class Transformation in Free Jazz PDFNilson Santos100% (2)

- Harrison 2003Document49 pagesHarrison 200314789630q100% (1)

- Ab-C-E ComplexDocument25 pagesAb-C-E ComplexFred FredericksNo ratings yet

- Composition Before Rameau Harmony, Figured Bass, and Style in The BaroqueDocument20 pagesComposition Before Rameau Harmony, Figured Bass, and Style in The BaroqueLuiz Henrique Mueller Mello100% (1)

- Arvo Part's "Magister LudiDocument5 pagesArvo Part's "Magister LudiIliya Gramatikoff100% (2)

- Double Horn ConcertoDocument29 pagesDouble Horn ConcertoJosef OtrhálekNo ratings yet

- Music Theory Spectr 2003 Hanninen 59 97Document39 pagesMusic Theory Spectr 2003 Hanninen 59 97John Petrucelli100% (1)

- Oxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 204.78.0.252 On Fri, 09 Sep 2016 06:06:18 UTCDocument4 pagesOxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 204.78.0.252 On Fri, 09 Sep 2016 06:06:18 UTCLody MoreNo ratings yet

- Principles of Formal Structure in Schumann's Early Piano Cycles - Peter KaminskyDocument20 pagesPrinciples of Formal Structure in Schumann's Early Piano Cycles - Peter KaminskyThéo AmonNo ratings yet

- Harmony in RomanticismDocument5 pagesHarmony in Romanticismtyk86c5cpbNo ratings yet

- Ton de Leeuw Music of The Twentieth CenturyDocument19 pagesTon de Leeuw Music of The Twentieth CenturyBen MandozaNo ratings yet

- 2020 - Beyhom From Praktika-3o-Synedrio-Tomea-PsaltikisDocument42 pages2020 - Beyhom From Praktika-3o-Synedrio-Tomea-PsaltikisandreirosuNo ratings yet

- Brook1994 The Symphonie Concertante Its Musical and Sociological Bases PDFDocument19 pagesBrook1994 The Symphonie Concertante Its Musical and Sociological Bases PDFViviana Carolina Jaramillo AlemánNo ratings yet

- Justin Lepany - SpectralMusicDocument12 pagesJustin Lepany - SpectralMusicdundun100% (4)

- 15 Isac IulianaDocument8 pages15 Isac IulianaBentley EdwardsNo ratings yet

- 745872Document28 pages745872ubirajara.pires1100100% (1)

- Music An Appreciation Brief 8th Edition Roger Kamien Solutions Manual 1Document13 pagesMusic An Appreciation Brief 8th Edition Roger Kamien Solutions Manual 1greg100% (52)

- Mozart's Topical Content in Keyboard SonatasDocument6 pagesMozart's Topical Content in Keyboard SonatasRobison Poreli100% (1)

- 2019 Tismir Sonata FormDocument16 pages2019 Tismir Sonata FormPeiling LuNo ratings yet

- The Diminutions On Composition and TheoryDocument31 pagesThe Diminutions On Composition and TheoryMarcelo Cazarotto Brombilla100% (2)

- Carissimi's Tonal System and The Function of Transposition in The Expansion of TonalityDocument43 pagesCarissimi's Tonal System and The Function of Transposition in The Expansion of TonalityFlávio Lima100% (1)

- The Concept of Mode in Italian Guitar Music During The First Half of The 17th Century Author(s) - Richard HudsonDocument22 pagesThe Concept of Mode in Italian Guitar Music During The First Half of The 17th Century Author(s) - Richard HudsonFrancisco Berény DominguesNo ratings yet

- Sonata FormDocument11 pagesSonata FormMészáros MátéNo ratings yet

- 1 The Austrian C-Major Tradition: Haydn Symphony 20 Opening - mp3 Haydn Symphony 48 Opening - mp3Document27 pages1 The Austrian C-Major Tradition: Haydn Symphony 20 Opening - mp3 Haydn Symphony 48 Opening - mp3laura riosNo ratings yet

- Stravinsky - The Progress of A Method - ConeDocument14 pagesStravinsky - The Progress of A Method - ConemangueiralternativoNo ratings yet

- A Physicist's View On Chopin's ÉtudesDocument15 pagesA Physicist's View On Chopin's ÉtudesCree100% (3)

- Harbinson-Boulez Third SonataDocument6 pagesHarbinson-Boulez Third SonataIgnacio Juan Gassmann100% (1)

- Writings - Notational Indetermincay in Musique Concrète InstrumentaleDocument18 pagesWritings - Notational Indetermincay in Musique Concrète InstrumentaleCesare Angeli80% (5)

- Schubert SeitenwechselDocument27 pagesSchubert SeitenwechselLuccaNo ratings yet

- Cycle (Music) - WikipediaDocument3 pagesCycle (Music) - WikipediaJohn EnglandNo ratings yet

- Autosimilar MelodiesDocument28 pagesAutosimilar MelodiesGonzalo Lacruz Esteban100% (1)

- The Structure of The Saeta FlamencaDocument32 pagesThe Structure of The Saeta FlamencaAnae Moreno Ramos100% (2)

- La Del Soto Del PerrralDocument15 pagesLa Del Soto Del PerrralyakartepeNo ratings yet

- Theory of Musical Materials and PrinciplesDocument22 pagesTheory of Musical Materials and PrinciplesyakartepeNo ratings yet

- 654321brahms Op.100 Pacing ScenariosDocument44 pages654321brahms Op.100 Pacing ScenariosyakartepeNo ratings yet

- Form Analysis Syllabus Spring 2022Document2 pagesForm Analysis Syllabus Spring 2022yakartepeNo ratings yet

- Example 1.10: Cadential ProgressionsDocument6 pagesExample 1.10: Cadential ProgressionsyakartepeNo ratings yet

- Music, Culture & Creativity "Final Project"Document3 pagesMusic, Culture & Creativity "Final Project"yakartepeNo ratings yet

- Asfsfeerr ff2314Document1 pageAsfsfeerr ff2314yakartepeNo ratings yet

- Searl 20th Century CounterpointDocument168 pagesSearl 20th Century Counterpointregulocastro513091% (11)

- CDFFFJKJKJK 34Document2 pagesCDFFFJKJKJK 34yakartepeNo ratings yet

- First Departmental Test in Mapeh 9: MusicDocument4 pagesFirst Departmental Test in Mapeh 9: MusicCristena Delos Santos DeondoNo ratings yet

- ČÍNSKA KLAVÍRNA HUDBA whole-LinEnPei-thesis PDFDocument137 pagesČÍNSKA KLAVÍRNA HUDBA whole-LinEnPei-thesis PDFTibsoNo ratings yet

- The Romantic Trumpet: Edward H. TarrDocument49 pagesThe Romantic Trumpet: Edward H. TarrHenri FelixNo ratings yet

- Baroque Fingerprints GuideDocument3 pagesBaroque Fingerprints Guiderosihol100% (1)

- Dallas Symphony Orchestra 20 - 21 Season Chron - FINALDocument9 pagesDallas Symphony Orchestra 20 - 21 Season Chron - FINALnicholas beehnerNo ratings yet

- MAPEH10 Module 3Document35 pagesMAPEH10 Module 3albaystudentashleyNo ratings yet

- Carl VineDocument106 pagesCarl VineLarry GoldsteinNo ratings yet

- Various Plane of Art 1Document2 pagesVarious Plane of Art 1Athena BendoNo ratings yet

- Booklet-8 573440Document10 pagesBooklet-8 573440JorgeNo ratings yet

- Netherlands - Tristan KeurisDocument1 pageNetherlands - Tristan KeurisEtnoalbanianNo ratings yet

- Programme Description Master of Music 2017Document77 pagesProgramme Description Master of Music 2017davidNo ratings yet

- Emily H. Green, Catherine Mayes (Eds.) - Consuming Music ZBORNIK - Individuals, Institutions, Communities, 1730-1830-University of Rochester Press (2017) PDFDocument265 pagesEmily H. Green, Catherine Mayes (Eds.) - Consuming Music ZBORNIK - Individuals, Institutions, Communities, 1730-1830-University of Rochester Press (2017) PDFMusic LayerNo ratings yet

- Modern Harpsichord Music A DiscographyDocument335 pagesModern Harpsichord Music A DiscographyDanielNo ratings yet

- Jubin's Graded RepertoireDocument5 pagesJubin's Graded RepertoirexenxooNo ratings yet

- Classicism PDFDocument4 pagesClassicism PDFbielriera100% (1)

- Sonatina and Serenata (For Flute and Guitar)Document24 pagesSonatina and Serenata (For Flute and Guitar)Bob Gibson100% (5)

- Bach's Influence on Four-Part HarmonyDocument3 pagesBach's Influence on Four-Part HarmonyFREIMUZIC0% (1)

- Berger Thesis Interpretations Solo Violin WorksDocument2 pagesBerger Thesis Interpretations Solo Violin WorksVlad IvanciaNo ratings yet

- Romantic Period Music Research ProjectDocument36 pagesRomantic Period Music Research ProjectKim John Bernas59% (22)

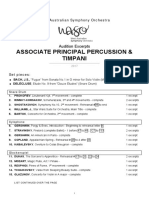

- Associate Principal Percussion and Timpani Excerpts 2017Document124 pagesAssociate Principal Percussion and Timpani Excerpts 2017chaohua fu100% (2)

- Brahms 72008 BookletDocument32 pagesBrahms 72008 BookletastridinloveNo ratings yet

- Example Repertoire For Flute: Baroque PeriodDocument2 pagesExample Repertoire For Flute: Baroque PeriodGilad RonenNo ratings yet

- Motivic Unity and Transformation in Mozart's D Minor Piano Concerto (K. 466)Document127 pagesMotivic Unity and Transformation in Mozart's D Minor Piano Concerto (K. 466)John MongioviNo ratings yet

- 9 - Music LM Q1Document30 pages9 - Music LM Q1Adrian Bagayan100% (1)

- St. Louis Symphony Extra - March 22, 2014Document16 pagesSt. Louis Symphony Extra - March 22, 2014St. Louis Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Performing Mozart's Clarinet Concerto With Improvised 18th-Century Embellishments by David AshtonDocument144 pagesPerforming Mozart's Clarinet Concerto With Improvised 18th-Century Embellishments by David AshtonDavid Ashton100% (1)

- Repertoire List for 1st Position TrapDocument8 pagesRepertoire List for 1st Position TrapMaria DoriNo ratings yet

- Franz Reizenstein Online Archive BiographyDocument4 pagesFranz Reizenstein Online Archive BiographyzanNo ratings yet

- Dittersdorf - Concertos I and II (Piano)Document63 pagesDittersdorf - Concertos I and II (Piano)Ricardo Bessa100% (2)

- Ingolf Dahl - S Concerto For Alto Saxophone and Wind Orchestra - A RDocument161 pagesIngolf Dahl - S Concerto For Alto Saxophone and Wind Orchestra - A Radwawd awdawdawNo ratings yet