Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Asesoramiento Premarital

Asesoramiento Premarital

Uploaded by

Gsus Calle FernandezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Asesoramiento Premarital

Asesoramiento Premarital

Uploaded by

Gsus Calle FernandezCopyright:

Available Formats

The Association for Family Therapy 2000.

Published by Blackwell Publishers, 108 Cowley

Road, Oxford, OX4 1JF, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

Journal of Family Therapy (2000) 22: 104–116

0163–4445

Premarital counselling: a focus for family therapy

Robert F. Stahmanna

Premarital counselling has not been identified as an area of practice in

recent surveys of family therapists. Yet this preventive approach is an area

that is receiving much attention worldwide as some governmental units are

requiring premarital counselling as a means to reduce divorce and

strengthen families. A descriptive overview of premarital counselling ratio-

nale, process, content and effectiveness is presented and the possible role

of family therapists offering this service is discussed.

Introduction

Today there is a growing movement for governmental units to seek

measures to strengthen families in society. In the UK in November

1998, The Home Secretary, Jack Straw, released the ‘Supporting

Families’ consultation paper aimed at shoring up families and to

provide resources to do so. It was proposed that churches, other

faiths and register offices would give a pre-marriage packet to a

couple before they married which would include a statement of

rights and responsibilities. Also under the proposal, couples would

be required to give notice (apply) of their intention to marry at

least fifteen days before the wedding, in contrast to the twenty-four-

hour notice now required (Ford, 1998).

In the UK and elsewhere (e.g. Australia, Austria, Canada, the

United States), these and similar preventive efforts are an attempt

to intervene with couples at the transition point of beginning

marriage in order to give them a better base for a stable and satis-

factory marriage. The stated aim is that by improving the prospec-

tive marital relationship divorce will be reduced as well as, and

hopefully related, problems such as domestic violence and child

abuse. Reductions in marital breakup would presumably enhance

a Professor, Marriage and Family Therapy, 240 TLRB, Brigham Young

University, Provo, UT 84602, USA.

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Premarital counselling 105

the mental and physical health of those involved, and the political

hope is that this would lead to a decrease in the amount of govern-

ment funds currently used for treating individuals and families and

coping with the societal consequences of marital breakdown.

Currently, therefore, there is much political interest in marriage

preparation and premarital counselling as services provided in the

community.

Premarital counselling and marital preparation

Premarital counselling generally refers to a process designed to

enhance and enrich premarital relationships leading to more satis-

factory and stable marriages with the intended consequence being

to prevent divorce. In remarital counselling, where one or both

partners have been previously married, there is the added dimen-

sion of dealing with how that experience, and any children from the

previous marital relationship, affects the current premarital rela-

tionship – this may well be linked to stepfamily issues. Both of these

activities can be termed marital preparation, with the other princi-

pal method of marital preparation in secular settings being family

life education. Premarital counselling is typically undertaken with

relatively functional and psychologically healthy people, whereas

severe problems are dealt with in longer term counselling or ther-

apy (Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997a). Typical goals of the various

approaches to marital preparation include: (1) easing the transition

from single to married life, (2) increasing couple stability and satis-

faction for the short and long term, (3) enhancing the communi-

cations skills of the couple, (4) increasing friendship and

commitment to the relationship, (5) increasing couple intimacy,

(6) enhancing problem-solving and decision-making skills in such

areas as marital roles and finances (Stahmann and Salts, 1993).

There are three main groups of people who directly provide or

oversee most premarital counselling: clergy, mental health workers

and physicians. These providers may also involve lay persons in the

role of mentors in their efforts to maximize the participants’ goals

of strengthening their forthcoming marriage. The evidence is that

the majority of premarital counselling is undertaken in church

settings, with a significant amount in other contexts however, such

as college and university counselling centres and training clinics

(e.g. marriage and family counselling training programme clinics),

community mental health centres, governmental family service

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

106 Robert F. Stahmann

agencies, and by mental health professionals in private practice.

Clergy, in performing the greatest amount of formal premarital

counselling, do so as part of an optional or mandatory marriage

preparation programme before a religious wedding ceremony or

service. Premarital preparation has been described from a Catholic

perspective (Markey, 1998), a Jewish perspective (Dalin, 1998), and

a Protestant perspective (Anderson, 1998). Physicians also under-

take some form of premarital counselling but this is usually limited

to one meeting where they give contraceptive and sexual informa-

tion. Professionals with a mental health background typically offer

premarital counselling most often to those who have been divorced,

are preparing to marry again, and who want to avoid another

divorce. Relate, the largest provider of couples counselling in the

UK, has a long history of providing marriage preparation. The prin-

cipal way it delivers this service is via educationally orientated

courses undertaken in co-operation with local churches. These

courses focus on communication, dealing with conflict and creating

an understanding of the life stages within marriage/relationships.

As would be expected, premarital counselling occurs when a couple

is in a relationship and is seeking to strengthen that relationship or

seeking information about (evaluating) it. Thus premarital coun-

selling is educational, remedial and preventive (Stahmann and

Hiebert, 1997a).

Family life education

In the United States, family life education programmes are found

in high schools and colleges, and more recently through commu-

nity adult education. Such courses and programmes are usually

structured so that participants gain knowledge about marriage

and relationships and learn to apply that knowledge in practical

ways. Therefore, goals may include information about marriage

(e.g. marriage statistics, marital satisfaction and stability factors),

skill development (e.g. communication, problem-solving, deci-

sion-making), exploring values and attitudes (e.g. marital expec-

tations, roles, beliefs), and family background (e.g. homogamy,

parenting). Specific goals in family life education classes differ

due to the varying ages and developmental levels of the partici-

pants.

The British educational system does not deal specifically with

family/marital education. It is expected that through a programme

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Premarital counselling 107

of personal, social and health education (PHSE) these issues will be

addressed. However, PHSE provision is varied from being almost

non-existent to professionally delivered. Under the current review

of the National Curriculum it is hoped that a new structured PHSE

programme will be established for all schools which will include

relationship education and sex education.

Effectiveness of marriage preparation

The effectiveness of marriage preparation, whether counselling or

educational, has not been clearly established. Much of the literature

is clinical observation or participant self-report regarding the

premarital counselling or educational experience (Giblin et al.,

1985; Stanley et al., 1995). A review of the literature related to

premarital counselling (Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997a) found that

most studies reported positive effects, while some showed minimal

or no effect of marriage preparation efforts. No studies have

demonstrated negative effects for couples or individuals who parti-

cipated in various marriage preparation programmes. The results

were often mixed, showing some areas of positive impact or change

and some showing no impact. It should be noted that in compari-

son to other areas of marital counselling and therapy, there are very

few outcome studies dealing with premarital counselling in the liter-

ature, with these studies varying greatly in treatment design, format

and scientific rigour. Yet there are some notable examples. In a

four-year follow-up of married couples who had participated in

PREP (prevention and relationship enhancement programme)

training, these couples demonstrated more positive and less nega-

tive communication than control couples, but the two groups did

not differ on marital adjustment (Markman et al., 1993). The latter

finding has not been fully explored however. Another study

(Hahlweg et al., 1998) reported a three-year follow-up of German

couples who participated in a premarital couple communications

and problem-solving skill programme similar to PREP. After three

years, participant couples, who were then married, showed signifi-

cant positive differences in regard to dissolution rates, relationship

satisfaction and positive communication behaviours in comparison

to a control group.

Parish (1992) studied the premarital assessment programme

(PAP) compared to a combined couples communication

programme and premarital assessment programme (CCPAP), but

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

108 Robert F. Stahmann

unfortunately there was no treatment control group. It was found

that the CCPAP, which combined communications training with the

premarital exercises of the PAP ( (1) dating history and wedding

plans; (2) expectations, roles, needs, goals; (3) family, finances,

friends, fun; (4) parents meeting; (5) communication and conflict;

(6) values and sexuality) yielded significant improvement on post-

test measures of dyadic adjustment and commitment to continu-

ance of the relationship. The provision of information about

content areas, such as those in the PAP in combination with

communications skill-building, appear to have some effectiveness in

achieving the short-term goals of marital preparation, but as yet the

achievement of long-term goals has not been demonstrated. Clearly

the beginnings of an empirical base for family therapists to design

and provide premarital counselling exists; however, they should

continue to study and refine the process in order to ensure the most

effective and appropriate outcomes. At a recent conference

discussing the potential of prevention as a means to deal with mari-

tal distress and divorce, University of Denver researchers Scott

Stanley and Howard Markman stated that ‘We should conduct more

research and we should act on the knowledge that currently exists’

(Stanley and Markman, 1997: 2).

Specific premarital programmes

The following is a brief overview of four approaches to premarital

counselling and education that have been widely used. These

programmes have stimulated research as to their effectiveness.

The relationship enhancement programme (RE) developed by

Bernard Guerney and colleagues at Pennsylvania State University is

among the earliest programmes developed, and one that continues

to be widely used and to stimulate research (Guerney, 1977;

Guerney et al., 1986). RE is a group programme focused on

strengthening and enhancing nine positive relationship factors by

increasing caring, giving, understanding, honesty, openness, trust,

sharing, compassion and harmony. Participants learn a set of nine

skills associated with these relationship factors. The idea is that as

couples achieve or enhance these nine skill areas, they will elimi-

nate and/or be better able to deal with pain and distress in their

relationship. Several studies have demonstrated that participants in

RE have shown significantly greater gains in relationship quality

and communication in comparison to wait list control groups

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Premarital counselling 109

(Guerney, 1988). The RE programme has been termed a health

promotion programme (Van Widenfeldt et al., 1997).

The prevention and relationship enhancement programme (PREP)

developed by Howard Markman and colleagues at the University of

Denver is also a group programme (Markman et al., 1994). In the

PREP approach, couples are taught skills in handling conflict (male

and female differences in handling conflict, the speaker-listener

technique, problem-solving), dealing with core issues (expecta-

tions, commitment, forgiveness and the restoration of intimacy),

and enhancement (friendship, fun, sex life, core belief systems).

PREP interventions are based on the idea that it is the negative

aspects of a couple’s relationship, not the positive aspects, that are

the important focus. In other words, it is the number of negatives,

not the number of positives, that break couples up. Therefore,

couples are taught what ineffective communication is, and are also

taught skills in effective communication. As cited above, PREP has

been shown to be effective in three- and five-year follow-up studies

with such variables as positive communication, relationship satisfac-

tion and marital stability. PREP has been termed a prevention

programme (Van Wedenfelt et al., 1997).

The prepare/enrich programme was developed by David Olson and

colleagues at the University of Minnesota as a means to provide

feedback to couples who had taken a premarital inventory,

PREPARE (Olson, 1996). PREPARE (PREmarital Personal And

Relationship Evaluation) assesses the eleven relationship areas of

marriage expectations, personality issues, communication,

conflict resolution, financial management, leisure activities,

sexual relationship, children and parenting, family and friends,

role relationship, and spiritual beliefs. A separate idealistic distor-

tion scale serves as a correction score for idealism. Four additional

scales assess cohesion and adaptability in the current couple rela-

tionship and each individual’s family of origin. The four person-

ality traits of assertiveness, self-confidence, avoidance of problems

and partner dominance are assessed. Once PREPARE is taken by

the couple, the results are sent for computer scoring. The coun-

sellor receives a computer report of the inventory results which

then become the basis for a three-session (or more) process of

counselling, outlined in a work book and guide furnished for the

counsellor and clients. The exercises and information focus on

identifying and sharing strength and growth areas, assertiveness

and active listening skills, resolving couple conflict, couple and

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

110 Robert F. Stahmann

family-of-origin types, financial management, and making goals a

reality. The PREPARE programme could be termed an inventory-

based programme.

The integrative premarital counselling programme (Stahmann and

Hiebert, 1997a) was developed by myself at Brigham Young

University and William Hiebert at the Marriage and Family

Counselling Service. This programme can be used with individual

couples or in groups. It assumes that couples can enhance their

relationship and thereby increase their likelihood of marital success

and satisfaction. It is termed integrative because it utilizes concepts,

skills and information from many aspects of family systems, marital

interaction and skill-building. Components of the integrative

approach include goal-setting and expectations of the counselling,

doing a ‘dynamic relationship history’ with the couple, exploring

each partner’s family of origin, the use of a premarital assessment

inventory such as PREPARE, FOCUS or RELATE, the inclusion of

relationship skill-building exercises from programmes such as RE

and PREP, information and discussion on topics and issues such as

commitment, marital and individual roles, finances, intimacy, sexu-

ality, careers, leisure activities, wedding preparation, etc. It is

suggested that, where possible, the couple’s parent(s) be invited to

a counselling session for the recognition of the ‘new’ married

couple and to pass on wisdom from one generation to the other. It

is also recommended that a post-wedding follow-up session be

scheduled for about six months after the wedding.

Family therapists and premarital counselling

Premarital counselling as defined above has not been identified as

a regular part of clinical practice of today’s family therapists. In two

recent surveys, one of UK family therapists who were members of

the Association of Family Therapy (AFT) (Bor et al., 1998) and

another of US family therapists who were members of the

American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT)

(Doherty and Simmons, 1996), premarital counselling was not

listed as a category of practice. In these surveys, the direct question

as to whether the therapists were involved in premarital coun-

selling was apparently not asked. Further, in both studies, the

results did show that none of the ‘client problems’ or ‘presenting

problems’ identified by therapists included the terms premarital or

remarital. While the surveys did indicate that the therapists

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Premarital counselling 111

reported working with stepfamily problems, post-divorce problems,

post-divorce conflict, adjustment disorders and other dyadic prob-

lems, it was not clear whether these client problems were related to

the therapeutic context of preparation for marriage by the clients.

Yet, in the early literature, directives are found for counsellors and

therapists to be involved in premarital counselling. Aaron Rutledge

argued that if all clinicians devoted a quarter of their time to

premarital counselling, they could make a greater impact on the

health of the country than through all their remaining therapeutic

activities (Rutledge, 1966). David Mace challenged marriage coun-

sellors to move out of the remedial routine and focus their ener-

gies on marriage preparation and marriage enrichment (Mace,

1972). More recently, premarital counselling by family therapists

was advocated at an international family therapy conference held

in Prague (Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997b).

Guidelines for premarital counselling

The following are research and clinically based guidelines and

points to consider for those who are designing premarital interven-

tions (Center for Marriage and Family, 1995; Jones and Stahmann,

1994; Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997a; Stanley et al., 1995). Those

seeking counselling or education prior to marriage are not all

unmarried, since counsellors report that 30% to 40% of their

premarital counselling clients were previously married (Stahmann

and Hiebert, 1997a). Those who benefit most from premarital

counselling must voluntarily seek it rather than be forced into it

(Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997a; Stanley et al., 1995). In the United

States, most married couples say that they would have participated

in such counselling if it had been offered (Center for Marriage and

Family, 1995; Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997a). Premarital coun-

selling needs to be seen as a developmental process designed to

assist the couple in enhancing their relationship – it is not a screen-

ing process (Jones and Stahmann, 1994; Stahmann and Hiebert,

1997a). The participants use the insights and information gained to

make decisions about their relationship (Center for Marriage and

Family, 1995). Persons requesting premarital counselling expect to

learn about themselves to some extent, but primarily to learn about

their relationship and each other (Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997a).

Much premarital counselling is done in groups with the advan-

tage that the group format is economical in that more couples can

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

112 Robert F. Stahmann

be served by fewer counsellors or leaders. A group experience also

provides a couple with the opportunity to compare and contrast

their relationship with others’. This can ‘normalize’ premarital and

marital adjustment in healthy ways. Groups also provide feedback

from others, and partners can observe how their future spouse

interacts with others in that setting. The limitations of group

format however include the specific need of some couples not be

addressed because of time constraints or programme design and

the domination of the group by one couple or theme. It may be

that some individuals or couples do not disclose or interact as

freely in a group setting, either because they are afraid of a group

situation or because they are not able to comfortably talk in a

group setting. Couples and counsellors favour conjoint sessions

rather than individual sessions. Clearly the advantages of meeting

with an individual couple alone are that the counsellor can focus

attention and energy on them instead of dealing with group

processes and issues. Topics can be personalized to meet the

couple’s specific needs and situation. Further, in conjoint work the

couple must focus on their own issues and skills, and cannot be

side-tracked by issues of others.

In settings where a team offers premarital counselling, such as

is often true in the Catholic Church, a team of clergy, lay couples

and parish staff has been rated as most helpful (Center for

Marriage and Family, 1995). The use of a comprehensive premar-

ital assessment instrument is a valuable component of the

premarital counselling process and contributes to it. It is impor-

tant that counsellors are aware of a range of topics such as

marriage quality and stability, family-of-origin influences,

finance/budgeting, communication, decision-making, intimacy,

parenting, sexuality, and use that information in the design and

delivery of the counselling and education. It is most beneficial if

obtained early on in the relationship and several months before

the wedding. While the number of sessions or meetings depends

upon many factors, there must be sufficient time spent in the

process, and it must be spread across an adequate time span so

that the partners can integrate the information and experience

into their lives. The offering of post-wedding follow-up session(s)

is an important part of premarital counselling. This session is

typically scheduled at the time of the last premarital session, for

a date some four to six months after the wedding (Stahmann and

Hiebert, 1997a).

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Premarital counselling 113

Moving forward

Throughout the world there is emerging an emphasis on both

remedial and preventive mental health services. Family therapists,

or psychotherapists with a family systems perspective and training,

are recognized as being among the most effective in treating a wide

variety of mental health and relationship problems. Today we are

seeing a tremendous expansion in preventive services, particularly

premarital counselling. ‘The existing body of research provides

substantial guidance regarding the key risk factors associated with

marital failure and the probable best strategies to attempt to modify

those risks’ (Stanley and Markman, 1997: 14). Fowers et al. (1996:

103) have argued that ‘marriage and family therapists are uniquely

positioned to offer their expertise in this area’.

Family therapists are in a natural position to take leadership in

premarital counselling. It has been argued that for a person to

adequately provide premarital counselling, graduate study at

Master’s level is necessary (Stahmann and Hiebert, 1997a). This

graduate study should include at least some training in relationship

counselling, marital interaction, family dynamics and assessment.

Family therapists typically have such training as well as a family

systems perspective. Thus family therapists may be excellent

providers of premarital counselling as they are in touch with every-

day marital stresses and problems, they are comfortable in talking

about ‘sensitive’ topics such as sex and emotions, and indeed they

are expected to be knowledgeable about long-term relationships

and the commitment and preparation necessary for them. On the

other hand, family therapists must approach this work with some

caution as they, in preferring the role of therapist rather than that

of psycho-educator, may focus too much on dysfunction and

pathology and be too ‘clinical’ in their work with premarital

couples. Family therapists would also need to address their lack of

awareness of the research and theories regarding marital satisfac-

tion, success, quality and stability.

Conclusion

It is certainly a tradition among various schools of psychotherapy

to advise on the nature of ‘health’ and suggest ways in which the

human condition can be approached so that satisfaction with life

is attained. Within this educational aspect of psychotherapeutic

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

114 Robert F. Stahmann

practice a preventive oriented activity is therefore something that

is worthwhile. As family therapy came into existence to help

ameliorate the problems and distress that are present in relation-

ships and families, premarital counselling is undoubtedly a prac-

tice activity that family and marital therapists should consider as

an area of service to offer.

References

Anderson, H. (1998) Marriage preparation: a protestant perspective. In H.

Anderson, D. S. Browning, I. S. Evison and M. S. Van Leeuwen (eds) The Family

Handbook (pp. 114–117). Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Bor, R., Mallandain, I. and Vetere, A. (1998) What we say we do: results of the 1997

UK Association of Family Therapy Members Survey. Journal of Family Therapy, 20:

333–351.

Center for Marriage and Family (1995) Marriage Preparation in the Catholic Church:

Getting it Right. Omaha, NE: Creighton University.

Crane, D. R. (1996) Fundamentals of Marital Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Dalin, R. S. (1998) Marriage preparation: a Jewish perspective. In H. Anderson, D.

S. Browning, I. S. Evison and M. S. Van Leeuwen (eds) The Family Handbook (pp.

111–113). Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Doherty, W. J. and Simmons, D. S. (1996) Clinical practice patterns of marriage

and family therapists: a national survey of therapists and their clients. Journal of

Marital and Family Therapy, 22: 9–25.

Ford, R. (1998) Straw aims to focus on the family (18 paragraphs) London Times

(Online) 8 November. Available: http//www. smartmarriages. com

Fowers, J. B., Montel, K. H. and Olson, D. H. (1996) Predicting marital success for

premarital couple types based on PREPARE. Journal of Marital and Family

Therapy, 22: 103–119.

Giblin, P., Sprenkle, D. H. and Sheehan, R. (1985) Enrichment outcome research:

a meta-analysis of premarital, marital, and family interventions. Journal of Marital

and Family Therapy, 11: 257–271.

Guerney, B. J. Jr (1977) Relationship Enhancement: Skill Training Program for Therapy

Problems Prevention and Enrichment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Guerney, B. J. Jr (1988) Family relationship enhancement: a skill training

approach. In L. Bond and B. Wagner (eds) Families in Transition: Primary

Prevention Programs That Work. Newbury Park: Sage.

Guerney, B. J. Jr, Brock, G. and Coufal, J. (1986) Integrating marital therapy and

enrichment: the relationship enhancement approach. In N. S. Jacobon and A.

S. Guerman (eds)Clinical Handbook of Marital Therapy (pp. 151–172). New York:

Guilford Press.

Hahlweg, K., Markman, H. J., Thurmaier, F., Engl, J. and Eckert, V. (1998)

Prevention of marital distress: results of a German prospective longitudinal

study. Journal of Family Psychology, 12: 543–556.

Jones, E. F. and Stahmann, R. F. (1994) Clergy beliefs, preparation, and practice

in premarital counseling. Journal of Pastoral Care, 48: 181–186.

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

Premarital counselling 115

Mace, D. R. (1972) We can have Better Marriages if we Really Want Them. Nashville,

TN: Abingdon Press.

Markey, B. (1998) Marriage preparation: a Catholic perspective. In H. Anderson,

D. S. Browning, I. S. Evison and M. S. Van Leeuwen (eds) The Family Handbook

(pp. 107–110). Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Markman, H. J., Stanley, S. M. and Blumberg, S. L. (1994) Fighting for your Marriage:

Positive Steps for Preventing Divorce and Preserving a Lasting Love. San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Markman, H. J., Renick, M. J., Floyd, F., Stanley, S. and Clements, M. (1993)

Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management

training: a 4- and 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61:

70–77.

Olson, D. H. (1996) PREPARE/ENRICH Counselor’s Manual. Minneapolis, MN: Life

Innovations, Inc.

Parish, W. E. (1992) A quasi-experimental evaluation of the premarital assessment

program for premarital counselling. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family

Therapy, 13: 33–36.

Rutledge, A. L. (1966) Premarital Counseling. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

Stahmann, R. F. and Hiebert, W. J. (1997a) Premarital and Remarital Counseling: The

Professional’s Handbook. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Stahmann, R. F. and Hiebert, W. J. (1997b) Approaches to marital preparation for

first marriages and remarriages in the USA. Paper presented at the Prague

Family Therapy Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, September.

Stahmann, R. F. and Salts, C. J. (1993) Educating for marriage and intimate rela-

tionships. In M. E. Arcus, J. D. Schvaneveldt and J. J. Moss (eds) Handbook of

Family Life Education (pp. 33–61). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Stanley, S. M. and Markman, H. J. (1997) Acting on what we know: the hope of

prevention. Family Impact Seminar, Washington, DC, June.

Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., St Peters, M. and Leber, D. B. (1995) Strengthening

marriages and preventing divorce: new directions in prevention research. Family

Relations, 44: 392–401.

Van Widenfelt, B., Markman, H. J., Guerney, B., Behrens, B. C. and Hosman, C.

(1997) Prevention of relationship problems. In Halford, W. K. and Markman,

H. J. (eds) Clinical Handbook of Marriage and Couples Interventions (pp. 651–675).

New York: Wiley.

Internet premarital counselling resources

A site providing information on ‘a review of research on marital

breakdown and reasons and remedies’ in the UK and other coun-

tries is found at {www.marriageresource.org.uk}

The site for One Plus One, ‘pioneers in marriage and relation-

ship support’ {http://www.oneplusone.org.uk} provides numerous

links to sites dealing with programmes, research, counselling,

education, funding, family health, and related topics.

The site for the Prepare/Enrich Network UK and UK

Community Marriage Policies {http://www.cmp.mcmail.com} provides

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

116 Robert F. Stahmann

information on assessment instruments and programmes to

strengthen marriages, as well as links to various related sites.

The site for the Coalition for Marriage, Family and Couples

Education (CMFCE) {http://smartmarriages.com} provides informa-

tion and articles from professional and popular press sources,

varied training opportunities and conferences, including the

annual Smart Marriages/Happy Families conference, and related

topics.

Sites for assessment instruments are: the FOCUS site for

Facilitating Open Communication, Understanding, & Study web site

is found at {http://www.foccusinc.com}; the PREPARE for PREmarital

Personal And Relationship Evaluation is found at web site

{http://www.lifeinnovation.com}; the RELATE for RELATionship

Evaluation web site is http://fhss.byu.edu/famsci/msc/relate.html}

2000 The Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- UGS 2024 ProgramDocument9 pagesUGS 2024 ProgramU of T MedicineNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Barry Case SolutionDocument2 pagesBarry Case SolutionSadia100% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Roadmap To A Successful Analytical Career at AgodaDocument6 pagesRoadmap To A Successful Analytical Career at Agodaggm2lokoNo ratings yet

- Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) Initial Competency Assessment and ValidationDocument2 pagesContinuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) Initial Competency Assessment and Validationalex100% (1)

- AssignmentDocument5 pagesAssignmentHELMA B. JABELLONo ratings yet

- DLL - Science 5 - Q2 - W4Document7 pagesDLL - Science 5 - Q2 - W4Mak Oy MontefalconNo ratings yet

- Heirs Legitime Under The Civil Code, As Amended: CC) andDocument4 pagesHeirs Legitime Under The Civil Code, As Amended: CC) andSamJadeGadianeNo ratings yet

- COBIT 5 FoundationDocument7 pagesCOBIT 5 Foundationhomsom25% (4)

- Quantitative ResearchDocument4 pagesQuantitative ResearchEve JohndelNo ratings yet

- Gender and Society-SageDocument23 pagesGender and Society-SagetentendcNo ratings yet

- Social MobilizationDocument12 pagesSocial MobilizationArianne A ZamoraNo ratings yet

- 10 PoemsDocument17 pages10 PoemsImran SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- SandboxDocument5 pagesSandboxdeepukr85No ratings yet

- EUST 1010 Course Guide Jan-Apr 2021Document11 pagesEUST 1010 Course Guide Jan-Apr 2021Chtsing TsangNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan On Domain and RangeDocument6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan On Domain and RangeLORIE JANE L. LETADA82% (11)

- Practicals PPBEDocument119 pagesPracticals PPBEDivyaraj JadejaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Art AppreciationDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Art AppreciationMaynalyn PamplonaNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 To BeDocument10 pagesUnit 4 To BeNUR AZIZAHNo ratings yet

- RRB Je Syllabus and Exam Pattern 2020: Useful LinksDocument7 pagesRRB Je Syllabus and Exam Pattern 2020: Useful LinksNiranjanNo ratings yet

- Boy Scout of The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesBoy Scout of The PhilippinesAngelo Andro SuanNo ratings yet

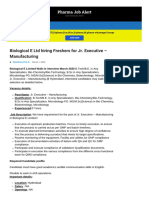

- Biological E LTD Hiring Freshers For Jr. Executive - ManufacturingDocument4 pagesBiological E LTD Hiring Freshers For Jr. Executive - Manufacturingనల్లమోతు సాయిరాం కుమార్No ratings yet

- Thesis Statistics FormulaDocument5 pagesThesis Statistics Formulafc34qtwg100% (2)

- Yr 3 Maths Homework SheetsDocument7 pagesYr 3 Maths Homework Sheetscfft1bcw100% (1)

- A Novel VSI-and CSI-Fed Dual Stator Induction Motor Drive Topology For Medium-Voltage Drive ApplicationsDocument10 pagesA Novel VSI-and CSI-Fed Dual Stator Induction Motor Drive Topology For Medium-Voltage Drive ApplicationsNagulapati KiranNo ratings yet

- LINQ Interactive Site Plan and Floor PlanDocument30 pagesLINQ Interactive Site Plan and Floor PlanasdfasNo ratings yet

- NSC 209 HEALTH AND PHYSICAL ASSESSMENTDocument99 pagesNSC 209 HEALTH AND PHYSICAL ASSESSMENTakoeljames8543No ratings yet

- Sticker Strips and Singles ReflectionDocument8 pagesSticker Strips and Singles Reflectionapi-251092359No ratings yet

- Not Necessary To Be Cited: Necessary To Be CitedDocument3 pagesNot Necessary To Be Cited: Necessary To Be CitedJunathan L. DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Mt1Pwr-Iia-I-5.1: Blend Specific Letters To Form Syllables and WordsDocument2 pagesMt1Pwr-Iia-I-5.1: Blend Specific Letters To Form Syllables and WordsKris LynnNo ratings yet

- Faculty Library Committee Meeting Minutes 2/11/09Document2 pagesFaculty Library Committee Meeting Minutes 2/11/09Kiran KumarNo ratings yet