Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stanislavski Method Handout

Uploaded by

JustynaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stanislavski Method Handout

Uploaded by

JustynaCopyright:

Available Formats

Sam Sloan – SPCM 201 – Stanislavsky and Emotion – Goes along with Ch.

7 in the Pelias/Schaffer – Page 1

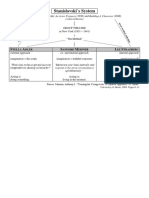

Stanislavski Method

Developed in the early 20th century at the Moscow Art Theater by Constantin Stanislavski, the Stanislavski method

of acting is a set of techniques meant to create realistic portrayals of characters. The major goal of the Stanislavski

method is to have a perfect understanding of the motivations, obstacles, and objectives of a character in each moment.

Actors often use this technique for realistic plays, where they try to present an accurate portrayal of normal life.

Three Core Elements

To begin employing the Stanislavski method, actors generally go over the script very carefully, looking for key

identifying factors. A performer discovers what a character wants (OBJECTIVE), what prevents the character from

getting it (OBSTACLE), and what means the character will use to achieve this goal (METHOD). Actors must also

determine the given circumstances of every scene, such as where the scene takes place, what is in the room, and what is

going on in the outside world. (For every performance, identify the objective of the scene, the obstacle in your way

and the method of getting around the obstacle. For some literature, like poetry, you may need to invent or discover the

obstacle or method through analysis or by playing around in performance).

Beginning with Objectives

To identify the objective clearly, an actor breaks down a scene into “beats” or “bits,” which are short sections that end

with each change of objective. In a basic example, if a character pours a cup of coffee, answers the phone, and then

runs screaming out of the house, the scene has at least three separate beats. At the bare minimum, the objective changes

from pouring coffee, to answering the phone, to getting out of the building. Beats are not determined on action alone,

however, and may be based on a change of argument or emotion. Actors can define objectives even within individual

lines of dialogue, based on a concept called “objective words.” It is the actor’s job to understand and play the

character’s objective not only in the entire play or film, each scene, and each beat, but also in each line. (In any

performance, determining what the key motivation is behind each line is a basic practice in the Stanislavski method.)

Obstacles and Methods Within a Scene

Obstacles are things preventing a character from achieving his or her objective. In the previous scene, if the character

trips while trying to run, it would present an obstacle to the objective of getting out of the house. Obstacles are dealt

with through one of three methods: the character gives up the objective because of it, finds a way to go around

it, or plunges along regardless. The method a character chooses in dealing with obstacles gives great insight into that

character; the basis for much of the Stanislavski method lies in defining how and why a character chooses a response.

The "Magic If"

In order to help actors portray the honest objective of the character, Stanislavski pioneered a concept called the “magic

if.” To help connect the character to the actor, performers must ask themselves “What if this situation happened to

me?” Through this activity, actors identify with characters as possible aspects of themselves, allowing them to think

like the characters, rather than just impersonate them. (Use yourself and your own emotional world as a model. Maybe

you’ve never had a parent die, for instance, but maybe you’ve lost a pet or other relative. Let that insight, those feelings

inform how you might play an emotion like “loss” in a character. Let your personal connections inform your

character’s world. — Also ask yourself questions like: What if this scene is the last time I ever get to see who I’m

talking to? What if I am secretly lying? What if I am in love? Let your answers inform your performance choices.)

The Internal Monologue

Understanding the objectives and methods of a character allows a performer to create an internal monologue for that

character (this can be very simple, like a mantra). Real people typically have a semi-constant flow of thoughts going on

in their minds, and the Stanislavski method attempts to create a internal monologue for a character. This technique

helps each action feel as if it comes spontaneously, rather than simply because the script says it should happen.

Sam Sloan – SPCM 201 – Stanislavsky and Emotion – Goes along with Ch. 7 in the Pelias/Schaffer – Page 2

Differences from "Method Acting"

Due of its emphasis on realism, the Stanislavski method is often used in modern plays, film, and television. It should

not be confused with Lee Strasberg’s “Method Acting,” however, which involves an actor attempting to completely

become a character. The Stanislavski method maintains that a performer must remain somewhat separate from the

character, in order to properly understand his or her motivations and goals.

(Compiled from http://www.wisegeek.org/what-is-the-stanislavski-method-of-acting.htm)

What If

During Stanislavsky's drama classes, students were asked to act out different scenarios. Stanislavsky would watch them

acting out mundane tasks such as losing a set of keys or looking for a handbag. He would watch them run aimlessly

around the stage, pretending to tear out their hair or feigning worry. He asked one of his students to imagine that the

keys were somewhere in the room. The actress then began to actually search for the keys rather than to act searching

for the keys. It is only when the imagination believes that the situation is real that the true feelings of the actress

are conveyed to the audience.

Example: A volunteer is to act as though they are walking down the street. The other students then ask... 'What if...' and

make a suggestion to the volunteer to act out a situation. This may be, 'What if you were attacked by an old lady'. It

may be appropriate that the other student becomes the old lady. The reactions to WHAT IF need to be spontaneous and

need to be as realistic and natural as possible. Examples include; 'What if you were hit by a bus?', then 'What if you

found out you broke your leg?' These are extreme examples – make your questions relevant to the text you are using.

Below are four of Stanislavski's acting principles, each illustrated by a simple acting exercise:

1) Using your imagination to create real emotions on stage

Stanislavski encouraged his students to use the magic if to believe in the circumstances of the play. Actors use their

imagination to answer questions like: "What if what happens in the scene was really happening to me?" "Where do I

come from?" "What do I want?" "Where am I going?" "What will I do when I get there?" (A simple exercise you can

do anywhere to develop your imagination is to simply observe people surrounding you as you go about your daily life

(for example, in the subway or at the coffee shop). Then, invent details about their lives and use observations to make

up a biography for each person. Try to write a similar biography of a character you're playing.)

2) Action versus Emotion

Stanislavsky encouraged his students to concentrate on actions rather than emotions. In every scene, the actor has an

objective (a goal of what he wants to accomplish) and faces a series of obstacles. To reach his goal, the actor breaks the

scene down into beats, with each beat being an active verb, something the character does to try to reach his objective.

Here are a few examples of active verbs that can be actions in scenes: To help To hurt To praise To demean To leave

To keep To convince... (A simple exercise to get used to this way of working is to get a piece of paper and continue this

list, adding as many active verbs as you can think of, that are appropriate for your character.)

3) Relaxation and Concentration

Actors who study Stanislavski's acting method learn to relax their muscles. The goal is to not use any extra muscles

than the ones needed to perform a particular action on stage. They also work on concentration so they can reach a state

of solitude in public and not feel tense when performing on stage. In this acting technique, relaxation and concentration

go hand in hand. (Here's a simple Stanislavski concentration exercise to get started… Close your eyes and concentrate

on every sound you hear, from the loudest to the most quiet: a door slamming in the distance, a ruffle of the leaves in

the trees outside, the hum of the air conditioner, etc. Try to focus solely on sounds, excluding everything else from your

mind. Next, open your eyes and try to retain the same amount of focus.)

4) Using the senses

Stanislavsky students practiced using their senses to create a sense of reality on stage. For example, if their character

just walked indoors and it was snowing outside, they may work on an exercise to remember what being outdoors in the

snow feels like so they can have a strong sense of where they're coming from. (Example: Close your eyes and imagine

you are outdoors in the snow, then ask yourself the following five questions:

What do you see? Is the snow pristine? Muddy? What do you smell? How cold is the air as it enters your nostrils? What

do you hear? Is it more quiet than usual? What do you feel? How does the snow feel? Is it sticky? Wet? Are your toes

cold? What do you taste? Imagine that a flake falls on your lips. How does it taste? Is your throat dry from the cold?

You might also like

- StanislavskiDocument4 pagesStanislavskiIrma MuminovićNo ratings yet

- ACTING General HandoutDocument4 pagesACTING General HandoutNagarajuNoolaNo ratings yet

- (Theatre Topics Vol. 12 Iss. 1) Barker, Sarah - The Alexander Technique - An Acting Approach (2002) (10.1353 - tt.2002.0002) - Libgen - LiDocument15 pages(Theatre Topics Vol. 12 Iss. 1) Barker, Sarah - The Alexander Technique - An Acting Approach (2002) (10.1353 - tt.2002.0002) - Libgen - LiBogdan TudoseNo ratings yet

- Sense Memory 01: Breakfast DrinkDocument4 pagesSense Memory 01: Breakfast DrinkJonathan Samarro100% (1)

- Roman Holiday ScreenplayDocument3 pagesRoman Holiday Screenplayeesheta_sharma1433No ratings yet

- Fourteen Steps To Teach Dyslexics 7 StepsDocument20 pagesFourteen Steps To Teach Dyslexics 7 StepsMischa SmirnovNo ratings yet

- Stanislavski TechniquesDocument2 pagesStanislavski Techniquesapi-509765058No ratings yet

- Sanford Meisner's Approach to Actor Training Focused on Action and ReactivityDocument1 pageSanford Meisner's Approach to Actor Training Focused on Action and ReactivityGiselle RoblesNo ratings yet

- 15 Minute Practitioners Uta HagenDocument8 pages15 Minute Practitioners Uta HagenJason ShimNo ratings yet

- Auditioning - Student HandoutDocument3 pagesAuditioning - Student Handoutapi-202765737No ratings yet

- Acting 'The Six Steps of Character Analysis'Document1 pageActing 'The Six Steps of Character Analysis'Lauren SchwecNo ratings yet

- Acting Presentation On StellaDocument7 pagesActing Presentation On Stellaapi-463306740No ratings yet

- About The Meisner Technique For ActorsDocument1 pageAbout The Meisner Technique For ActorsTeresa Cheung actressNo ratings yet

- Acting Techniques: Body Language Facial Expression Campy Marshall NeilanDocument3 pagesActing Techniques: Body Language Facial Expression Campy Marshall NeilanMarathi CalligraphyNo ratings yet

- GOTE: The Four Basic ElementsDocument12 pagesGOTE: The Four Basic ElementsMeditatii Lumina100% (2)

- Fourteen Play AnalysisDocument2 pagesFourteen Play AnalysisAlthea VallejosNo ratings yet

- Script Analysis Worksheet 4mip 2014Document1 pageScript Analysis Worksheet 4mip 2014api-202765737No ratings yet

- A Higher Calling Phillip Seymor HoffmanaDocument14 pagesA Higher Calling Phillip Seymor Hoffmanaalchymia_ilNo ratings yet

- Tips For Student ActorsDocument2 pagesTips For Student ActorsKatie Norwood AlleyNo ratings yet

- Training Young Actors PhysicallyDocument147 pagesTraining Young Actors Physicallyasslii_83No ratings yet

- Character Analysis FullDocument3 pagesCharacter Analysis FullElla SwinfordNo ratings yet

- Theatre Semester ExamDocument4 pagesTheatre Semester ExamAutumnNo ratings yet

- Michael Shurtleff's 12 Guideposts:: A Roadmap To Creating Honest, Truthful Behavior in An Audition SettingDocument25 pagesMichael Shurtleff's 12 Guideposts:: A Roadmap To Creating Honest, Truthful Behavior in An Audition SettingJennifer Mitchell100% (1)

- List of Vocal Exercises.Document2 pagesList of Vocal Exercises.RupeshBavisker0% (2)

- Guide To Self Taping Success by Mark Westbrook Acting Coach ScotlandDocument29 pagesGuide To Self Taping Success by Mark Westbrook Acting Coach ScotlandОля Мовчун100% (1)

- Stani Week by WeekDocument9 pagesStani Week by WeekJanetDoeNo ratings yet

- Blueprint: PREPARATION For First Read: 2 Hours of No Interruption - Phones Off!!!Document7 pagesBlueprint: PREPARATION For First Read: 2 Hours of No Interruption - Phones Off!!!TeneishaCNo ratings yet

- 2 2 Year 7 Drama Lesson Plan 2 Week 7Document7 pages2 2 Year 7 Drama Lesson Plan 2 Week 7api-229273655100% (1)

- 4 Ways To Prepare For Pilot Season Like A Pro Copyright Amy Jo Berman 2019Document10 pages4 Ways To Prepare For Pilot Season Like A Pro Copyright Amy Jo Berman 2019Zaarin BushraNo ratings yet

- Meyerhold's Key Theoretical PrinciplesDocument27 pagesMeyerhold's Key Theoretical Principlesbenwarrington11100% (1)

- Script Analysis NotesDocument29 pagesScript Analysis NotesBrian IrelandNo ratings yet

- Moscow Art TheatreDocument37 pagesMoscow Art TheatreDan BuckNo ratings yet

- A Kid and A Hit Man - 1 Man 1 Girl 12Document4 pagesA Kid and A Hit Man - 1 Man 1 Girl 12doryNo ratings yet

- A Concise Introduction To Verbatim TheatreDocument21 pagesA Concise Introduction To Verbatim TheatreSimon MichaelNo ratings yet

- Mindmap - Varieties of The MethodDocument1 pageMindmap - Varieties of The MethodJanetDoeNo ratings yet

- 12 Steps To Prepare Your Monologue PDFDocument4 pages12 Steps To Prepare Your Monologue PDFThandoNo ratings yet

- HOT IDEAS FOR THEATRE CLASS OPENINGSDocument84 pagesHOT IDEAS FOR THEATRE CLASS OPENINGSshindigzsariNo ratings yet

- Actor Training and Emotions - Finding A BalanceDocument317 pagesActor Training and Emotions - Finding A Balanceعامر جدونNo ratings yet

- Beats and Beat Changes - Marie SchraderDocument2 pagesBeats and Beat Changes - Marie SchraderAdam MontagueNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Physical Theatre - Viewpoints - Noa RotemDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Physical Theatre - Viewpoints - Noa Rotemxanderkhan100% (1)

- Action Verbs/objectives For ActorsDocument1 pageAction Verbs/objectives For ActorsChris Little100% (1)

- Stanislavakian Acting As PhenomenologyDocument21 pagesStanislavakian Acting As Phenomenologybenshenhar768250% (2)

- Working With ActorsDocument21 pagesWorking With ActorsJoel BrandãoNo ratings yet

- Sitcom Stock CharactersDocument2 pagesSitcom Stock Charactersjensnow221No ratings yet

- A Disappearing Number Resource PackDocument7 pagesA Disappearing Number Resource PackOolagibNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Scenes For Young Actors 8-2016Document100 pagesContemporary Scenes For Young Actors 8-2016ethanfrenemiesNo ratings yet

- Andrew Lloyd WebberDocument3 pagesAndrew Lloyd Webberprincess2011No ratings yet

- CLOWN WORKOUTS On Facebook by Holly Stoppit and Robyn HambrookDocument5 pagesCLOWN WORKOUTS On Facebook by Holly Stoppit and Robyn HambrookNg Shiu Hei LarryNo ratings yet

- Stanislavsky Script AnalysisDocument14 pagesStanislavsky Script AnalysisMD SYAKLINE ARAFATNo ratings yet

- Intro To Acting - Sixteen Keys To CharacterizationDocument4 pagesIntro To Acting - Sixteen Keys To CharacterizationKogunNo ratings yet

- Margolin Deb Oh, I WillDocument13 pagesMargolin Deb Oh, I WillLjubisa MaticNo ratings yet

- Chap04 PDFDocument155 pagesChap04 PDFJonathan ReevesNo ratings yet

- Acting NotesDocument3 pagesActing Notesapi-676894540% (1)

- Woyzeck SchemeDocument12 pagesWoyzeck SchemeElenaNo ratings yet

- Drama 252 Spring 2017 SyllabusDocument6 pagesDrama 252 Spring 2017 SyllabusElliott ChinnNo ratings yet

- Books and Resources for Acting Training and Career DevelopmentDocument2 pagesBooks and Resources for Acting Training and Career DevelopmentamarghitoaieiNo ratings yet

- Handout - General American AccentDocument1 pageHandout - General American AccentJustynaNo ratings yet

- Handout - Group PrinciplesDocument1 pageHandout - Group PrinciplesJustynaNo ratings yet

- Handout - Consolidation ChecklistDocument2 pagesHandout - Consolidation ChecklistJustynaNo ratings yet

- Handout - Character Questions From HotseatingDocument3 pagesHandout - Character Questions From HotseatingJustyna100% (1)

- LA LA LAND SceneDocument7 pagesLA LA LAND SceneJustynaNo ratings yet

- WC ScreenwritingDocument3 pagesWC ScreenwritingJustynaNo ratings yet

- 16 Blocks by Richard Wenk PDFDocument109 pages16 Blocks by Richard Wenk PDFSureshKumarNo ratings yet

- Asst2 StudentsDocument4 pagesAsst2 StudentsRyan DolmNo ratings yet

- Final Demo Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesFinal Demo Lesson Planagalot kennethNo ratings yet

- TÀI LIỆU ÔN TẬP (gửi cho sinh viên)Document22 pagesTÀI LIỆU ÔN TẬP (gửi cho sinh viên)Nguyễn Ngọc HuyNo ratings yet

- Mark Twain Thesis Research PaperDocument5 pagesMark Twain Thesis Research Paperfc2qyaet100% (2)

- Phyllis Creme, Mary Lea-Writing at University-Open University Press (2008) PDFDocument234 pagesPhyllis Creme, Mary Lea-Writing at University-Open University Press (2008) PDFJairo AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Oracle® Fusion Middleware: Release Notes For Oracle HTTP Server 12c (12.2.1)Document14 pagesOracle® Fusion Middleware: Release Notes For Oracle HTTP Server 12c (12.2.1)jawadNo ratings yet

- Basics of Using Discontinuation Data: Creation of Production Order With Discontinued Material (Transaction CO01)Document9 pagesBasics of Using Discontinuation Data: Creation of Production Order With Discontinued Material (Transaction CO01)RjNo ratings yet

- Quarter 3Document6 pagesQuarter 3Princess Nicole LugtuNo ratings yet

- Pali English DictionaryDocument712 pagesPali English DictionaryIoan AndreescuNo ratings yet

- Java Interview Questions - TutorialspointDocument18 pagesJava Interview Questions - TutorialspointRohit RasalNo ratings yet

- Present Perfect Tense QuizDocument4 pagesPresent Perfect Tense QuizAnonymous MH69nbyrYNo ratings yet

- Sams Asp Dotnet Evolution Isbn0672326477Document374 pagesSams Asp Dotnet Evolution Isbn0672326477paulsameeNo ratings yet

- History and Meaning of Our National FlagDocument5 pagesHistory and Meaning of Our National FlagJarvin Lois Vivit BasobasNo ratings yet

- Mathematics - Solution - DPP - A1 - A10 (Sip-Jee-Xi)Document25 pagesMathematics - Solution - DPP - A1 - A10 (Sip-Jee-Xi)Kraken BenderNo ratings yet

- 9th English Socialscience 2Document160 pages9th English Socialscience 2Manoj BENo ratings yet

- Buri NazarDocument2 pagesBuri NazarS1536097F0% (1)

- Use of Dramatic Dialogue in Robert FrostDocument6 pagesUse of Dramatic Dialogue in Robert FrostMohan Kalawate50% (6)

- Digital Signal ProcessingDocument2 pagesDigital Signal ProcessingPokala CharantejaNo ratings yet

- Lkc-Fes Y1S3 L1 Ms. Tan Jue XinDocument3 pagesLkc-Fes Y1S3 L1 Ms. Tan Jue XinXin HuiNo ratings yet

- (GK) Indian Culture (Arts, Religion, Entertainment) : Which of The Statements Gives Is/are Correct?Document7 pages(GK) Indian Culture (Arts, Religion, Entertainment) : Which of The Statements Gives Is/are Correct?Anupam BidyarthiNo ratings yet

- Ibnu Thufail's Islamic Philosophy in His Work "Hayy Ibn YaqzhanDocument8 pagesIbnu Thufail's Islamic Philosophy in His Work "Hayy Ibn YaqzhanTya ShofarinaNo ratings yet

- Courtesy, Ceremonial, and Contest Speeches GuideDocument10 pagesCourtesy, Ceremonial, and Contest Speeches GuideSteps RolsNo ratings yet

- Certified Data Scientist Brochure Datamites India V6.5Document22 pagesCertified Data Scientist Brochure Datamites India V6.5AmarNo ratings yet

- 1o BACH September Grammar and Vocabulary ActivitiesDocument45 pages1o BACH September Grammar and Vocabulary ActivitiesemmagutierrezruizNo ratings yet

- Department of Information Technology: SRM Institute of Science and Technology Ramapuram Campus Cycle Test - IDocument2 pagesDepartment of Information Technology: SRM Institute of Science and Technology Ramapuram Campus Cycle Test - IAshutosh DevpuraNo ratings yet

- Math 237 Mid Term Exam Set ADocument8 pagesMath 237 Mid Term Exam Set AShunsui SyNo ratings yet

- John FOWLSDocument7 pagesJohn FOWLSTah ReemNo ratings yet

- Introduction to ASP.NET Web FormsDocument107 pagesIntroduction to ASP.NET Web FormsmcguledNo ratings yet